Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

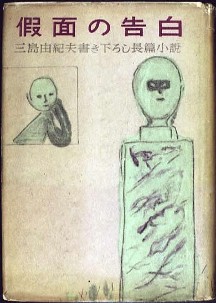

Confessions of a Mask

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (December 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

Confessions of a Mask (仮面の告白, Kamen no Kokuhaku) is the second novel by Japanese author Yukio Mishima. First published on 5 July 1949 by Kawade Shobō,[1][2] it launched him to national fame though he was only in his early twenties.[3] Some have posited that Mishima's similarities to the main character of the novel come from the character acting as a stand-in for Mishima's own autobiographical story.

Key Information

The novel is divided into four long chapters, and is written using the first-person narrative mode.

The book's epigraph is a lengthy quote from The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoevsky ("The Penance of a Fervent Heart—Poem" in Part 3, Book 3).

Confessions of a Mask was translated into English by Meredith Weatherby for New Directions in 1958.[4]

Background and composition

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2024) |

After resigning from the Ministry of Finance in September 1948, Mishima planned to begin work on a novel at the request of his publisher, Kawade Shobō, though it took him two months to decide exactly what form it should take. Writing to editor Sakamoto Kazuki, Mishima declared:

"This next novel will be my first I-novel ever; of course, it won't be an I-novel of the Literary Establishment sort, but it will be an attempt to vivisect myself in which I will turn on myself the blade of psychological analysis that I have honed for the hypothetical figure so far. I will aim for as much scientific accuracy as I can; I will try to be Baudelaire's so-called 'victim and executioner.'"[a]

Mishima would later compare his Confessions to Vita Sexualis by Mori Ōgai and Armance by Stendhal.[5]

Plot

[edit]The protagonist is referred to in the story as Kochan, which is the diminutive of the author's real name: Kimitake (公威). Being raised during Japan's era of right-wing militarism and Imperialism, he struggles from a very early age to fit into society. Like Mishima, Kochan was born with a less-than-ideal body in terms of physical fitness and robustness, and throughout the first half of the book (which generally details Kochan's childhood), he struggles intensely to fit into Japanese society.[6] A weak homosexual, Kochan is kept away from boys his own age as he is raised, and is thus not exposed to the norm. His isolation likely led to his future fascinations and fantasies of death, violence, and same-sex intercourse.[7]

Kochan is homosexual,[3] and in the context of Imperial Japan, he struggles to keep it to himself. In the early portion of the novel, Kochan does not yet openly admit that he is attracted to men, but indeed professes that he admires masculinity and strength while having no interest in women. This includes an admiration for Roman sculptures and statues of men in dynamic physical positions. Some have argued that the admiration of masculinity is autobiographical of Mishima, himself having worked hard through a naturally weak body to become stronger and a male model.

In the first chapter of the book, Kochan recalls a memory of a picture book from when he was four years old. Even at that young age, Kochan approached a single picture of a heroic-looking European knight on horseback almost as pornography, gazing at it longingly and hiding it away, embarrassed, when others came to see what he was doing. When his nurse tells him that the knight is actually Joan of Arc, Kochan, wanting the knight to be a paragon of manliness, is immediately and forever put off by the picture, annoyed that a woman would dress in men's clothing.

The word "mask" comes from how Kochan develops his own false personality that he uses to present himself to the world. Early on, as he develops a fascination with his friend Omi's body during puberty, he believes that everybody around him is also hiding their true feelings from each other, everybody participating in a "reluctant masquerade". As he grows up, he tries to fall in love with a girl named Sonoko, but is continuously tormented by his latent homosexual urges, and is unable to ever truly love her.[3]

Reception

[edit]The initial reception of Confessions of a Mask in the English-speaking world was somewhat mixed, but ultimately positive; over time, this autobiographical novel came to be seen as one of Mishima's most important works.

An anonymous reviewer for Kirkus Reviews opines: "As a novel there is very little to recommend this painful account of retarded sexuality, but as a testament to the current enthusiasm with which the Japanese have embraced Western literary traditions of the last forty years at the expense of their own heritage, Confessions of a Mask makes a grim and forceful impression."[8]

In the New York Times, Ben Ray Redman writes: "This book will increase American awareness of [Mishima's] skill; but it will also, I imagine, arouse in many readers as much distaste as respect . . . In Confessions of a Mask a literary artist of delicate sensibility and startling candor, has chosen to write for the few rather than the many."[9]

Writing for the Japan Times, Iain Maloney notes that: "In many ways Confessions is the key text to understanding Mishima's later novels. In it, he explores the poles of his psyche, his homosexuality and his romantic/erotic attraction to warfare and combat. It is a scathing, unflinching examination of the darkness at the far corners of the human mind."[10]

Christopher Isherwood, as quoted in The Mattachine Review, proclaimed, after reading the novel: "Here is a Japanese Gide."[11]

Further reading

[edit]- Exquisite Nothingness: The Novels of Yukio Mishima by David Vernon (Endellion Press, 2025, ISBN 978-1739136130). Chapter One: 'Confessions of a Mask: Personality and Performance', pp.69-82

References

[edit]- ^ A reference to Baudelaire's poem "The Self-Tormentor" ("L'Héautontimorouménos"), which appears in The Flowers of Evil.

- ^ 佐藤秀明; 井上隆史; 山中剛史 (August 2005). 決定版 三島由紀夫全集42巻 年譜・書誌. Shinchosha. pp. 391–393. ISBN 978-4-10-642582-0.

- ^ 佐藤秀明; 井上隆史; 山中剛史 (August 2005). 決定版 三島由紀夫全集42巻 年譜・書誌. Shinchosha. pp. 540–561. ISBN 978-4-10-642582-0.

- ^ a b c "Confessions of a Mask". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- ^ Petersen, Gwenn Boardman (1979). The Moon in the Water: Understanding Tanizaki, Kawabata, & Mishima. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. p. 319. ISBN 0824805208.

- ^ Inose, Naoki (2012). Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima (Expanded ed.). Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 168–9, 172. ISBN 9781611720082.

- ^ "仮面の告白 (Kamen no Kokuhaku)". Nihon Kokugo Daijiten (日本国語大辞典) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- ^ "仮面の告白 (Kamen no kokuhaku)". Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (日本大百科全書(ニッポニカ) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- ^ "Book Reviews, Sites, Romance, Fantasy, Fiction". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 2024-03-17.

- ^ "What He Had to Hide". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2024-03-17.

- ^ Maloney, Iain (2015-04-04). "Mishima's weakling in a world of military machismo in 'Confessions of a Mask'". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2024-03-17.

- ^ Mattachine Review. Mattachine Society. 1959.

External links

[edit]Confessions of a Mask

View on GrokipediaContext and Authorship

Yukio Mishima's Early Influences and Biography

Yukio Mishima, born Kimitake Hiraoka on January 14, 1925, in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo, grew up in a family shaped by his father's position as a government official in the Ministry of Agriculture.[8] His early years were dominated by his paternal grandmother, Natsuko, who took custody of him shortly after birth and enforced a regimented routine that isolated him from his parents and emphasized cultural refinement over physical play.[9] This environment instilled a sense of fragility and introspection, as Mishima was confined indoors, shielded from rough activities, and immersed in traditional arts such as kabuki theater and noh drama, which his grandmother favored.[10] From childhood, Mishima displayed a precocious literary bent, composing poems and stories by age six or seven, drawing initially from Japanese classics like The Tale of Genji and noh plays, alongside folktales and the bushido code.[10] His reading expanded to Western authors during adolescence, including Oscar Wilde, Edgar Allan Poe, and Jean Cocteau, whose decadent aesthetics and explorations of beauty and mortality resonated with his emerging sensibilities.[11] These influences blended with modern Japanese writers like Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, fostering a stylistic hybrid that marked his early prose—elegant yet introspective, often probing themes of concealment and idealization.[12] During World War II, Mishima's physical frailty became starkly evident when he was rejected for military service by the Imperial Japanese Army due to perceived weakness, later attributed to conditions like pleurisy.[13] Instead, he contributed to the war effort through civilian labor in a Tokyo aircraft factory, an experience that deepened his fixation on martial valor and bodily perfection, ideals he contrasted against his own perceived inadequacies.[14] This rejection fueled a lifelong tension between intellectual pursuits and the pursuit of physical rigor, evident in his post-war bodybuilding regimen. Mishima's literary career began in earnest during the war years; at age 16, he published his first story outside school magazines, followed by his debut novella Hanazakari no Mori (The Forest in Full Bloom) in 1944, which showcased his ornate style but garnered limited attention amid wartime constraints.[15] By 1948, his novel Tōzoku (Thieves) achieved modest critical notice, establishing his reputation for psychological depth and signaling the maturity that would culminate in Confessions of a Mask the following year.[16] These early works, rooted in his sheltered upbringing and wartime frustrations, laid the groundwork for his semi-autobiographical exploration of hidden identities.Post-War Japanese Society

Japan surrendered unconditionally on September 2, 1945, aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, marking the end of World War II and the onset of Allied occupation.[17] Under General Douglas MacArthur's Supreme Command for the Allied Powers, the occupation from 1945 to 1952 pursued demilitarization by disbanding the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, purging wartime leaders, and enacting a new constitution in 1947 that renounced war and emphasized pacifism.[18] These reforms accelerated a shift from state-directed militarism to democratic institutions, including women's suffrage and labor rights, yet generated friction as traditional hierarchies clashed with externally imposed egalitarian principles.[19] Economic devastation compounded societal strains, with hyperinflation peaking at over 500% annually by 1946 and food rationing providing fewer than 1,500 calories per day per person in urban areas.[20] Black markets, known as yami ichi, surged in cities like Tokyo, where vendors—often including demobilized soldiers, Koreans, and Taiwanese—hawked rice, clothing, and cigarettes at prices 10 to 20 times official rates, sustaining survival amid official distribution failures.[21] Youth, comprising a demographic bulge from pre-war births, faced disrupted education and employment; schools reopened sporadically under resource shortages, while many adolescents scavenged or labored informally, eroding pre-war emphases on collective discipline and filial piety in favor of individualistic adaptation.[22] The occupation's ideological overhaul targeted bushido-influenced militarism, promoting textbooks that omitted glorification of imperial expansion and samurai ethics, which had been codified in the early 20th century to underpin national loyalty.[23] This contributed to a perceived dilution of traditional values like stoic endurance and emperor reverence, though pockets of imperial nostalgia endured among conservatives lamenting the 1945 renunciation of divine sovereignty.[18] National defeat induced widespread existential disillusionment, with suicide rates climbing to 20 per 100,000 by 1947 as veterans and civilians grappled with shattered purpose, fostering a cultural milieu where introspective narratives began to supplant wartime propaganda.[24]Composition and Publication

Writing Process and Challenges

Mishima composed Confessions of a Mask primarily between 1947 and 1949, shortly after graduating from the University of Tokyo, while employed in the banking division of the Japanese Ministry of Finance.[25] Balancing daytime bureaucratic responsibilities with nocturnal writing sessions, he adhered to a disciplined routine that allowed steady progress on the manuscript despite the demands of his entry-level civil service role.[25] This period of secrecy stemmed from the novel's exploration of taboo themes, including same-sex desire, which carried significant social stigma in post-war Japan, prompting Mishima to veil personal elements through fictional layering rather than overt confession.[26] Drawing from the shishōsetsu (I-novel) tradition of introspective, semi-autobiographical narration prevalent in modern Japanese literature, Mishima subverted expectations by infusing empirical observations of psychological concealment with dense symbolism, avoiding the genre's typical raw sincerity.[27] His approach emphasized causal mechanisms of identity suppression, informed by personal experiences of frailty and evasion—such as his earlier deferment from military service due to claimed tuberculosis amid actual respiratory vulnerabilities—yet channeled into stylized detachment rather than direct reportage.[28] Extensive revisions refined the prose for precision, merging classical Japanese aesthetic sensibilities with Western psychoanalytic influences to evoke beauty amid inner turmoil, without yielding to unmediated autobiography.[29] These iterative efforts addressed stylistic challenges in harmonizing lush, sensory descriptions with narrative restraint, ensuring the mask motif served as a structural device for thematic depth rather than mere confessional release.[30] Mishima's method underscored a commitment to artistic control, transforming potential vulnerabilities into a cohesive exploration of human dissimulation.Publication Details and Immediate Aftermath

, the original Japanese title of Confessions of a Mask, was published on July 5, 1949, by Kawade Shobō in Tokyo.[31] At the time of release, Yukio Mishima was 24 years old, and the novel marked a pivotal breakthrough, establishing him as a prominent figure in post-war Japanese literature despite initial slow sales.[32] The publication occurred during the Allied occupation of Japan, a period characterized by resource shortages including paper rationing, which constrained print runs and distribution for many literary works, though specific figures for this title remain undocumented in available records.[33] The novel's domestic success propelled Mishima's career, shifting public and critical attention toward his exploration of personal identity within traditional societal frameworks, subtly contributing to a resurgence of introspective literary voices amid occupation-era constraints on overt nationalism.[34] In the immediate aftermath, it garnered attention for its stylistic maturity, positioning Mishima among emerging authors navigating the transition from wartime austerity to renewed cultural expression. An English translation by Meredith Weatherby appeared in 1958, published by New Directions in the United States, introducing the work to Western audiences during a period of increasing curiosity about Japanese fiction in the post-war era.[33] This translation, praised for its fidelity, facilitated early international dissemination and laid groundwork for Mishima's global recognition, though broader acclaim developed gradually.[35]Narrative Structure and Content

Plot Summary

The narrative commences with protagonist Kochan's introspective account of his birth, vividly recalled amid a pool of blood that his mother perceives as an ill omen.[1] In early childhood, confined to his grandmother's upstairs quarters to shield his frail health from contagion, Kochan indulges in solitary pursuits, including war games evoking noble deaths on the battlefield, while recurrent illnesses nearly claim his life.[1][36] His initial attractions manifest toward figures embodying beauty and tragedy, such as an image initially believed to depict a male knight but revealed as Joan of Arc, followed by a profound fixation on Guido Reni's depiction of Saint Sebastian bound and pierced by arrows. This encounter precipitates Kochan's sexual awakening, prompting him to compose a prose poem about the saint, while he recognizes an absence of desire for female peers.[1][36] During middle school, Kochan develops an obsession with classmate Omi, a delinquent exuding robust masculinity that underscores his own physical weakness, leading him to reject these feelings and strive to toughen his body in emulation of military cadets.[1][36] As World War II escalates, Kochan endures air raids that drive his family into Tokyo's bomb shelters, intensifying his seclusion amid the city's devastation, and he resorts to concealing his inclinations behind a constructed normalcy.[36] Enrolled in university, Kochan feigns conventionality by pursuing Sonoko, sister of acquaintance Kusano, assisting her family through wartime hardships yet experiencing no authentic affection; exempted from frontline duty by health issues, he labors in a fighter plane factory.[1][36] The association with Sonoko advances toward prospective marriage, but Kochan severs it amid mounting self-loathing; in the postwar period, she weds another, his sister perishes, and upon tentative reconnection, his underlying disquiet surfaces during an encounter at a dance hall.[1][36]Key Characters and Development

Kochan, the first-person narrator and protagonist, charts an evolution from passive childhood observer to deliberate architect of deception, his frailty—manifest in physical weakness and early fascinations with violent iconography like the Saint Sebastian painting—giving way to calculated performances of conformity. Born in 1925 and raised amid wartime Tokyo, he navigates adolescence through secretive desires sparked by peers, adopting a "mask" of refined heterosexuality by age 14 to evade ostracism, as evidenced by his feigned engagements during school evacuations and air raids that amplify existential precarity. This arc peaks in early adulthood with his courtship of Sonoko, where aspirational normalcy strains against underlying impulses, rendering him an unreliable chronicler whose selective monologues obscure as much as they reveal.[5][37][38] Supporting characters propel Kochan's trajectory through targeted causal influences within a sparse ensemble akin to Japanese social realism. The grandmother, his primary custodian, enforces a traditional, insular upbringing in her quarters, immersing him in classical aesthetics and dependency that anchor his initial introspections while shielding him from modern disruptions until her influence wanes. Omi, a muscular older classmate encountered in middle school, ignites Kochan's erotic jealousy during cohabited dormitory life, catalyzing a shift from latent fixation to active renunciation amid shared wartime hardships. Sonoko, a post-war acquaintance noted for her beauty and piano skills, embodies the normative ideal Kochan pursues, her reciprocal affections enabling his performative romance yet exposing the fragility of his adaptations during societal recovery.[5] Peripheral figures, including distant parents and transient schoolmates, intersect episodically with historical contingencies like military drafts and blackouts, furnishing minimal but pivotal drivers for Kochan's concealments without independent arcs, thereby concentrating narrative momentum on his evolving facades.[38][5]Themes and Literary Analysis

The Mask as Metaphor for Concealment

In Confessions of a Mask, the mask functions as a multifaceted metaphor for Kochan's strategic concealment of his inner vulnerabilities, enabling navigation through Japan's conformist social structures where overt deviation invites exclusion. This imagery manifests in literal disguises, such as applying cosmetics to obscure physical weakness and adopting exaggerated mannerisms to project vitality, serving as pragmatic adaptations to external demands for homogeneity.[39] These acts reflect a core causal mechanism: societal pressures compel individuals to fabricate external facades, prioritizing collective harmony over personal candor, as evidenced by Kochan's deliberate performances in daily interactions to avert suspicion.[1] The novel's recurring motifs of masking—drawn from cultural precedents like the stylized anonymity in traditional Japanese performance arts—underscore concealment not as mere symbolism but as a survival tactic rooted in observable human responses to rigidity. Kochan's "elaborate disguise of [his] true self" illustrates this, where feigned normalcy shields against judgment while fostering incremental self-deception, gradually blurring the boundary between adopted role and authentic identity.[40] Such adaptations, while initially functional, impose mounting cognitive loads, as the dissonance between concealed essence and public persona accumulates without outlet.[4] Contrasting the masked state, episodes of inadvertent exposure precipitate heightened internal turmoil, manifesting as profound exhaustion and detachment, with Kochan experiencing "spiteful fatigue" and a liminal existence "neither alive nor dead."[39] This dynamic reveals the realist consequences of prolonged concealment: unbridled inner impulses, when surfacing, exacerbate psychological strain through unresolved tension, eroding equilibrium without invoking pathology, but highlighting the unsustainable costs of evasion in a pressure-laden milieu.[41] The motif thus empirically traces how adaptive masking, essential for short-term endurance, evolves into a vector for deeper self-estrangement when societal imperatives preclude authentic expression.[30]Explorations of Sexuality and Desire

The protagonist Kochan experiences his earliest stirrings of erotic desire upon encountering an image of Saint Sebastian, whose lithe, wounded form embodies a fusion of physical beauty and vulnerability to violence, igniting a compulsive fascination with male anatomy.[37] This attraction recurs through encounters with robust male figures, such as the muscular night-soil man whose excretions Kochan inhales with secretive thrill and soldiers whose wartime vigor evokes both admiration and destructive potential.[39] These desires are depicted not as an immutable trait but as an insurgent impulse that fractures Kochan's adherence to societal imperatives of masculinity and filial obligation amid Japan's militaristic ethos.[37][39] Kochan's overtures toward heterosexuality, particularly his courtship of Sonoko, function as calculated performances to veil his inclinations, yet they yield no authentic erotic reciprocity, underscoring the insufficiency of such expedients for inner appeasement.[39] This pragmatic masking highlights a broader indictment of post-war indulgences, where superficial liaisons fail to quell the protagonist's deeper aesthetic and corporeal yearnings, positioning desire as antithetical to mere sensual gratification.[37] Scholarly readings diverge on these portrayals: certain analyses identify masochistic undertones in Kochan's recurrent violent reveries toward male ideals, interpreting them as self-perpetuating torment rather than cathartic release.[39] Others emphasize an evasive stoicism that sidesteps confrontation, rendering the narrative's tension unresolved and resistant to framings as a precursor to emancipatory self-disclosure.[39][37] Such perspectives counter reductive applications of contemporary identity paradigms, privileging the text's emphasis on desire's corrosive interplay with cultural conformance.[37]Aesthetics of Beauty, Death, and Tradition

In Confessions of a Mask, Mishima employs imagery of the youthful male physique to evoke an aesthetic ideal rooted in classical Japanese reverence for transience, akin to the ephemerality celebrated in historical traditions such as mono no aware. This idealization counters perceived frailty in contemporary existence by drawing on the disciplined ethos of samurai culture, where physical perfection in youth symbolized vitality and readiness for honorable extinction. Literary devices like vivid, sensual descriptions of lithe forms underscore this as an antidote to decay, reflecting Mishima's philosophical assertion that true beauty inheres in forms poised between vigor and dissolution.[39][37] Death emerges as the erotic apotheosis within the novel's aesthetic framework, causally intertwined with the inadequacies of mundane life to confer ultimate significance on mortality. Mishima's prose links erotic fulfillment to visions of violent demise, portraying death not as negation but as the consummation that elevates ephemeral beauty to transcendent meaning, a motif drawn from undiluted contemplation of life's inherent insufficiencies. This reasoning posits mortality as the forge of aesthetic intensity, where the pinnacle of desire aligns with self-annihilation, evoking visceral responses through rhythmic, incantatory language that merges pleasure and peril.[5][42] The work critiques post-war Japan's materialistic drift by contrasting it with traditional imperatives of rigorous self-discipline, valorizing aesthetic adherence to ancestral codes over modern commodification. Mishima's narrative devices, such as symbolic oppositions between austere historical valor and postwar complacency, highlight discipline as preservative of authentic beauty against societal erosion. Through precise, evocative prose—achieving stylistic innovation in blending archaic lyricism with psychological depth—the novel realizes a visceral aesthetics that privileges classical purity, substantiating tradition's causal role in sustaining cultural vitality amid decay.[43][4]