Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fiction

View on Wikipedia

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying individuals, events, or places that are imaginary or in ways that are imaginary.[1][2][3] Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent with fact, history, or plausibility. In a traditional narrow sense, fiction refers to written narratives in prose – often specifically novels, novellas, and short stories.[4][5] More broadly, however, fiction encompasses imaginary narratives expressed in any medium, including not just writings but also live theatrical performances, films, television programs, radio dramas, comics, role-playing games, and video games.

Definition and theory

[edit]| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Typically, the fictionality of a work is publicly expressed, so the audience expects a work of fiction to deviate to a greater or lesser degree from the real world, rather than presenting for instance only factually accurate portrayals or characters who are actual people.[6] Because fiction is generally understood as not adhering to the real world, the themes and context of a fictional work, such as if and how it relates to real-world issues or events, are open to interpretation.[7] Since fiction is most long-established in the realm of literature (written narrative fiction), the broad study of the nature, function, and meaning of fiction is called literary theory, and the narrower interpretation of specific fictional texts is called literary criticism (with subsets like film criticism and theatre criticism also now long-established). Aside from real-world connections, some fictional works may depict characters and events within their own context, entirely separate from the known physical universe: an independent fictional universe. The creative art of constructing such an imaginary world is known as worldbuilding.[8]

Literary critic James Wood argues that "fiction is both artifice and verisimilitude", meaning that it requires both creative inventions as well as some acceptable degree of believability to its audience,[9] a notion often encapsulated in the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge's idea of the audience's willing suspension of disbelief. The effects of experiencing fiction, and the way the audience is changed by the new information they discover, has been studied for centuries. Infinite fictional possibilities themselves signal the impossibility of fully knowing reality, provocatively demonstrating philosophical notions, such as there potentially being no criterion to measure constructs of reality.[10]

Fiction and reality

[edit]Fiction versus non-fiction

[edit]In contrast to fiction, creators of non-fiction assume responsibility for presenting information and sometimes opinion based only in historical and factual reality. Despite the traditional view that fiction and non-fiction are opposites, some works (particularly in the modern era) blur this boundary, particularly works that fall under certain experimental storytelling genres—including some postmodern fiction, autofiction,[11] or creative nonfiction like non-fiction novels and docudramas—as well as the deliberate literary fraud of falsely marketing fiction as nonfiction.[12]

Furthermore, even most works of fiction usually have elements of, or grounding in, truth of some kind, or truth from a certain point of view. The distinction between the two may be best defined from the viewpoint of the audience, according to whom a work is non-fiction if its people, settings, and plot are perceived entirely as historically or factually real, while a work is regarded as fiction if it deviates from reality in any of those areas.

All types of fiction invite their audience to explore real ideas, issues, or possibilities using an otherwise imaginary setting or using something similar to reality, though still distinct from it.[note 1][note 2]

Speculative versus realistic fiction

[edit]The umbrella genre of speculative fiction is characterized by a lesser degree of adherence to realistic or plausible individuals, events, or places, while the umbrella genre of realistic fiction is characterized by a greater degree. For instance, speculative fiction may depict an entirely imaginary universe or one in which the laws of nature do not strictly apply (often, the sub-genre of fantasy). Or, it depicts true historical moments, except that they have concluded in a completely imaginary way or been followed by major new events that are completely imaginary (the genre of alternative history). Or, it depicts impossible technology or technology that defies current scientific understandings or capabilities (the genre of science fiction).

Contrarily, realistic fiction involves a story whose basic setting (time and location in the world) is, in fact, real and whose events could believably happen in the context of the real world. One realistic fiction sub-genre is historical fiction, centered around true major events and time periods in the past.[15] The attempt to make stories feel faithful to reality or to more objectively describe details, and the 19th-century artistic movement that began to vigorously promote this approach, is called literary realism, which incorporates some works of both fiction and non-fiction.

History

[edit]Storytelling has existed in all human cultures, and each culture incorporates different elements of truth and fiction into storytelling. Early fiction was closely associated with history and myth. Greek poets such as Homer, Hesiod, and Aesop developed fictional stories that were told first through oral storytelling and then in writing. Prose fiction was developed in Ancient Greece, influenced by the storytelling traditions of Asia and Egypt. Distinctly fictional work was not recognized as separate from historical or mythological stories until the imperial period. Plasmatic narrative, following entirely invented characters and events, was developed through ancient drama and New Comedy.[16] One common structure among early fiction is a series of strange and fantastic adventures as early writers test the limits of fiction writing. Milesian tales were an early example of fiction writing in Ancient Greece and Italy. As fiction writing developed in Ancient Greece, relatable characters and plausible scenarios were emphasized to better connect with the audience, including elements such as romance, piracy, and religious ceremonies. Heroic romance was developed in medieval Europe, incorporating elements associated with fantasy, including supernatural elements and chivalry.[17]

The structure of the modern novel was developed by Miguel de Cervantes with Don Quixote in the early-17th century.[18] The novel became a primary medium of fiction in the 18th and 19th centuries. They were often associated with Enlightenment ideas such as empiricism and agnosticism. Realism developed as a literary style at this time.[19] New forms of mass media developed in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, including popular-fiction magazines and early film.[20] Interactive fiction was developed in the late-20th century through video games.[21]

Elements

[edit]Certain basic elements define all works of narrative, including all works of narrative fiction. Namely, all narratives include the elements of character, conflict, narrative mode, plot, setting, and theme. Characters are individuals inside a work of story, conflicts are the tension or problem that drives characters' thoughts and actions, narrative modes are the ways in which a story is communicated, plots are the sequence of events in a story, settings are the story's locations in time and space, and themes are deeper messages or interpretations about the story that its audience is left to discuss and reflect upon.[citation needed]

Formats

[edit]

Traditionally, fiction includes novels, short stories, fables, legends, myths, fairy tales, epic and narrative poetry, plays (including operas, musicals, dramas, puppet plays, and various kinds of theatrical dances). However, fiction may also encompass comic books, and many animated cartoons, stop motions, anime, manga, films, video games, radio programs, television programs (comedies and dramas), etc.

The Internet has had a major impact on the creation and distribution of fiction, calling into question the feasibility of copyright as a means to ensure royalties are paid to copyright holders.[22] Also, digital libraries such as Project Gutenberg make public domain texts more readily available. The combination of inexpensive home computers, the Internet, and the creativity of its users has also led to new forms of fiction, such as interactive computer games or computer-generated comics. Countless forums for fan fiction can be found online, where loyal followers of specific fictional realms create and distribute derivative stories. The Internet is also used for the development of blog fiction, where a story is delivered through a blog either as flash fiction or serial blog, and collaborative fiction, where a story is written sequentially by different authors, or the entire text can be revised by anyone using a wiki.[citation needed]

Fiction writing

[edit]Literary fiction

[edit]The definition of literary fiction is controversial. It may refer to any work of fiction in a written form. However, various other definitions exist, including a written work of fiction that:

- does not fit neatly into an established genre (as opposed to so-called genre fiction), when used as a marketing label in the book trade

- is character-driven rather than plot-driven

- examines the human condition

- uses language in an experimental or poetic fashion

- is considered serious as a work of art[23]

Literary fiction is often used as a synonym for literature, in the narrow sense of writings specifically considered to be an art form.[24] While literary fiction is sometimes regarded as superior to genre fiction, the two are not mutually exclusive, and major literary figures have employed the genres of science fiction, crime fiction, romance, etc., to create works of literature. Furthermore, the study of genre fiction has developed within academia in recent decades.[25]

The term is sometimes used such as to equate literary fiction to literature. The accuracy of this is debated. Neal Stephenson has suggested that, while any definition will be simplistic, there is today a general cultural difference between literary and genre fiction. On the one hand literary authors nowadays are frequently supported by patronage, with employment at a university or a similar institution, and with the continuation of such positions determined not by book sales but by critical acclaim by other established literary authors and critics. On the other hand, he suggests, genre fiction writers tend to support themselves by book sales.[26] However, in an interview, John Updike lamented that "the category of 'literary fiction' has sprung up recently to torment people like me who just set out to write books, and if anybody wanted to read them, terrific, the more the merrier. ... I'm a genre writer of a sort. I write literary fiction, which is like spy fiction or chick lit".[27] Likewise, on The Charlie Rose Show, he argued that this term, when applied to his work, greatly limited him and his expectations of what might come of his writing, so he does not really like it. He suggested that all his works are literary, simply because "they are written in words".[28]

Literary fiction often involves social commentary, political criticism, or reflection on the human condition.[29] In general, it focuses on "introspective, in-depth character studies" of "interesting, complex and developed" characters.[29] This contrasts with genre fiction where plot is the central concern.[30] Usually in literary fiction the focus is on the "inner story" of the characters who drive the plot, with detailed motivations to elicit "emotional involvement" in the reader.[citation needed] The style of literary fiction is often described as "elegantly written, lyrical, and ... layered".[31] The tone of literary fiction can be darker than genre fiction,[32] while the pacing of literary fiction may be slower than popular fiction.[32] As Terrence Rafferty notes, "literary fiction, by its nature, allows itself to dawdle, to linger on stray beauties even at the risk of losing its way".[33]

Genre fiction

[edit]Based on how literary fiction is defined, genre fiction may be a subset (written fiction that aligns to a particular genre), or its opposite: an evaluative label for written fiction that comprises popular culture, as artistically or intellectually inferior to high culture. Regardless, fiction is commonly broken down into a variety of genres: categories of fiction, each differentiated by a particular unifying tone or style; set of narrative techniques, archetypes, or other tropes; media content; or other popularly defined criterion.[citation needed]

Science fiction predicts or supposes technologies that are not realities at the time of the work's creation: Jules Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon was published in 1865, but only in 1969 did astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin become the first humans to land on the Moon.[citation needed]

Historical fiction places imaginary characters into real historical events. In the 1814 historical novel Waverley, Sir Walter Scott's fictional character Edward Waverley meets a figure from history, Bonnie Prince Charlie, and takes part in the Battle of Prestonpans. Some works of fiction are slightly or greatly re-imagined based on some originally true story, or a reconstructed biography.[34] Often, even when the fictional story is based on fact, there may be additions and subtractions from the true story to make it more interesting. An example is Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried, a 1990 series of short stories about the Vietnam War.

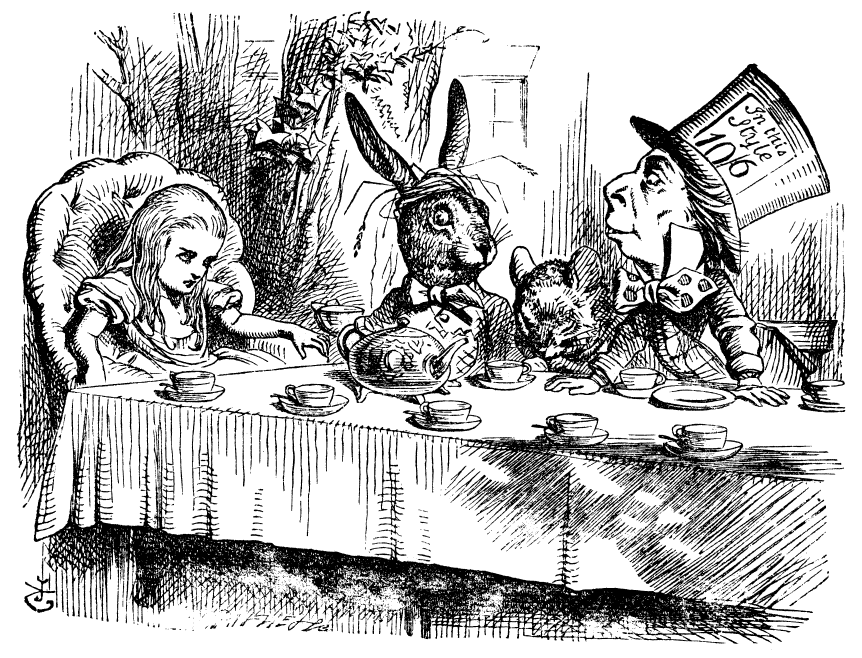

Fictional works that explicitly involve supernatural, magical, or scientifically impossible elements are often classified under the genre of fantasy, including Lewis Carroll's 1865 novel Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, and J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series. Creators of fantasy sometimes introduce imaginary creatures and beings such as dragons and fairies.[3]

Types by word count

[edit]Types of written fiction in prose are distinguished by relative length and include:[35][36]

- Short story: the boundary between a long short story and a novella is vague,[37] although a short story commonly comprises fewer than 7,500 words

- Novella: typically, 17,500 to 40,000 words in length; examples include Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) or Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (1899)[38]

- Novel: 40,000 words or more in length

Process of fiction writing

[edit]Fiction writing is the process by which an author or creator produces a fictional work. Some elements of the writing process may be planned in advance, while others may come about spontaneously. Fiction writers use different writing styles and have distinct writers' voices when writing fictional stories.[39]

Fictionalization as a concept

[edit]

The use of real events or real individuals as direct inspiration for imaginary events or imaginary individuals is known as fictionalization. The opposite circumstance, in which the physical world or a real turn of events seem influenced by past fiction, is commonly described by the phrase "life imitating art". The latter phrase is popularity associated with the Anglo-Irish fiction writer Oscar Wilde.[40]

The alteration of actual happenings into a fictional format, with this involving a dramatic representation of real events or people, is known as both fictionalization, or, more narrowly for visual performance works like in theatre and film, dramatization. According to the academic publication Oxford Reference, a work set up this way will have a "narrative based partly or wholly on fact but written as if it were fiction" such that "[f]ilms and broadcast dramas of this kind often bear the label 'based on a true story'." In intellectual research, evaluating this process is a part of media studies.[41]

Examples of prominent fictionalization in the creative arts include those in the general context of World War II in popular culture and specifically Nazi German leaders such as Adolf Hitler in popular culture and Reinhard Heydrich in popular culture. For instance, American actor and comedian Charlie Chaplin portrayed the eccentric despot Adenoid Hynkel in the 1940 satirical film The Great Dictator. The unhinged, unintelligent figure fictionalized real events from the then ongoing Second World War, in a way that presented fascist individuals as humorously irrational and pathetic. Many other villains take inspiration from real people while having fictional accents, appearances, backgrounds, names, and so on.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ As philosopher Stacie Friend explains, "in reading we take works of fiction, like works of non-fiction, to be about the real world – even if they invite us to imagine the world to be different from how it actually is. [Thus], imagining a story world does not mean directing one's imagining toward something other than the real world; it is instead a mental activity that involves constructing a complex representation of what a story portrays".[13]

- ^ The research of Weisberg and Goodstein (2009) revealed that, despite not being specifically informed that, say, the fictional character Sherlock Holmes, had two legs, their subjects "consistently assumed that some real-world facts obtained in fiction, although they were sensitive to the kind of fact and the realism of the story."[14]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "fiction". Lexico. Oxford University Press. 2019. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019.

- ^ Sageng, John Richard; Fossheim, Hallvard J.; Larsen, Tarjei Mandt, eds. (2012). The Philosophy of Computer Games. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-9400742499. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ a b Harmon, William; Holman, C. Hugh (1990). A Handbook to Literature (7th ed.). New York: Prentice Hall. p. 212.

- ^ Abrams, M. h. (1999). A Glossary of Literary Terms (7th ed.). Fort Worth, Texas: Harcourt Brace. p. 94.

- ^ ""Definition of 'fiction". Oxford English Dictionaries (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2015. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ Farner, Geir (2014). "Chapter 2: What is Literary Fiction?". Literary Fiction: The Ways We Read Narrative Literature. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1623564261. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Culler, Jonathan (2000). Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-19-285383-7.

Non-fictional discourse is usually embedded in a context that tells you how to take it: an instruction manual, a newspaper report, a letter from a charity. The context of fiction, though, explicitly leaves open the question of what the fiction is really about. Reference to the world is not so much a property of literary [that is, fictional] works as a function they are given by interpretation.

- ^ Hamilton, John (2009). You Write It: Science Fiction. Edina, Minn.: ABDO. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-61714-655-8. OCLC 767670861.

- ^ Wood, James (2008). How Fiction Works. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. xiii.

- ^ Young, George W. (1999). Subversive Symmetry. Exploring the Fantastic in Mark 6: 45–56. Leiden: Brill. pp. 98, 106–109. ISBN 90-04-11428-9.

- ^ Iftekharuddin, Frahat, ed. (2003). The Postmodern Short Story: Forms and Issues. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 23. ISBN 978-0313323751. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Menand, Louis (2018). "Literary Hoaxes and the Ethics of Authorship". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022.

- ^ Friend, Stacie (2017). "The Real Foundation of Fictional Worlds" (PDF). Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 95: 29–42. doi:10.1080/00048402.2016.1149736. S2CID 54200723. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Goodstein, Joshua; Weisberg, Deena Skolnick (2009). "What Belongs in a Fictional World?". Journal of Cognition and Culture. 9 (1–2): 69–78. doi:10.1163/156853709X414647.

- ^ Kuzminski, Adrian (1979). "Defending Historical Realism". History and Theory. 18 (3): 316–349. doi:10.2307/2504534. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 2504534.

- ^ Whitmarsh, Tim (2013). "The "Invention of Fiction"". Beyond the Second Sophistic: Adventures in Greek Postclassicism. University of California Press. pp. 11–34. doi:10.1525/california/9780520276819.001.0001. ISBN 978-0520957022. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Dunlop, John Colin (1845). The History of Fiction (3rd ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 46, 55–56.

- ^ Johnson, Carroll B. (2000). Don Quixote: The Quest for Modern Fiction. Waveland Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1478609148.

- ^ Chodat, Robert (2015). "The Novel". In Carroll, Noël; Gibson, John (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Literature. Routledge. pp. 83–. doi:10.4324/9781315708935. ISBN 978-1-315-70893-5. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Kristin (2003). Storytelling in Film and Television. Harvard University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0674010635.

- ^ Niesz, Anthony J.; Holland, Norman N. (1984). "Interactive Fiction". Critical Inquiry. 11 (1): 110–129. doi:10.1086/448277. ISSN 0093-1896. S2CID 224795950. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Jones, Oliver. (2015). "Why Fan Fiction is the Future of Publishing Archived 19 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. " The Daily Beast. The Daily Beast Company LLC.

- ^ Farner, Geir (2014). Buy Literary Fiction: The Ways We Read Narrative Literature by Geir Farner online in India – Bookchor. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1623560249. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Literature: definition". Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew (2010). "Popular Fiction Studies: The Advantages of a New Field". Studies in Popular Culture. 33 (1): 21–23.

- ^ "Neal Stephenson Responds With Wit and Humor". Slashdot.org. 20 October 2004. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Grossman, Lev (28 May 2006). "Old Master in a Brave New World". Time.

- ^ "The Charlie Rose Show from 14 June 2006 with John Updike". Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b Saricks 2009, p. 180.

- ^ Saricks 2009, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Saricks 2009, p. 179.

- ^ a b Saricks 2009, p. 182.

- ^ Rafferty 2011.

- ^ Whiteman, G.; Phillips, N. (13 December 2006). "The Role of Narrative Fiction and Semi-Fiction in Organizational Studies". ERIM Report Series Research in Management. ISSN 1566-5283. SSRN 981296.

- ^ Milhorn, H. Thomas (2006). Writing Genre Fiction: A Guide to the Craft Archived 28 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Universal Publishers: Boca Raton. pp. 3–4.

- ^ "What's the definition of a 'novella,' 'novelette,' etc.?". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009.

- ^ Cuddon, J. A., The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms (1992). London: Penguin Books, 1999, p. 600.

- ^ Heart of Darkness Novella by Conrad Archived 9 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine – Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Doyle, Charlotte L. (1 January 1998). "The Writer Tells: The Creative Process in the Writing of Literary Fiction". Creativity Research Journal. 11 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1207/s15326934crj1101_4. ISSN 1040-0419.

- ^ "Council Post: Management Styles and Machine Learning: A Case of Life Imitating Art". Forbes.

- ^ "Fictionalization". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

References

[edit]- Rafferty, Terrence (4 February 2011). "Reluctant Seer". The New York Times Sunday Book Review. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- Saricks, Joyce (2009). The Readers' Advisory Guide to Genre Fiction (2nd ed.). ALA Editions. p. 402. ISBN 9780838909898.

Further reading

[edit]- Eco, Umberto (15 July 2017). "On the ontology of fictional characters: A semiotic approach". Sign Systems Studies. 37 (1/2): 82–98. doi:10.12697/SSS.2009.37.1-2.04.

External links

[edit]- "Kate Colquhoun on the blurred boundaries between fiction and non-fiction", La Clé des Langues, 11 September 2012.

- Example of a Serial Blog/Short Story Magazine Archived 20 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

Fiction

View on GrokipediaFiction consists of narratives produced with fictive intent, where the primary constraint on their construction is imaginative possibility rather than fidelity to actual events, distinguishing them from non-fictional accounts that prioritize empirical accuracy.[1] This form encompasses literature, film, theater, and other media that depict invented characters, plots, and worlds, often to entertain, provoke reflection, or simulate social and emotional experiences.[2] Rooted in human cognitive capacities for pretense and abstraction, fiction enables the exploration of hypothetical scenarios without real-world consequences, functioning as a mental simulation of behaviors and outcomes.[3] The practice traces to ancient civilizations, with precursors in Mesopotamian epics and Greek romances that blended myth and narrative invention, evolving through medieval tales into the modern novel during the 17th and 18th centuries amid the rise of print culture and individualistic perspectives.[4] Key developments include the picaresque and realist traditions, which expanded fiction's scope to critique society and delve into psychological depths, as seen in works by Cervantes and Defoe.[5] By the 19th and 20th centuries, genres diversified into science fiction, fantasy, and literary modernism, reflecting technological advances and shifting epistemologies.[6] Fiction's societal impacts include modest enhancements to social cognition, such as improved theory of mind and empathy, through vicarious engagement with diverse perspectives, supported by psychological studies linking reading habits to better interpersonal understanding.[7][8] However, it carries risks of epistemic distortion, as immersive narratives can foster false beliefs or emotional biases if audiences conflate simulated events with reality, underscoring the need for critical discernment between pretense and fact.[9] Philosophically, ancient critics like Plato condemned fiction as thrice-removed imitation that deceives by prioritizing appearance over truth, yet modern analyses frame it as non-deceptive pretense that illuminates causal patterns in human behavior without asserting literal veracity.[2] These tensions highlight fiction's dual role as both a tool for cognitive expansion and a potential vector for misapprehension, contingent on reception and cultural context.[10]

Definition and Conceptual Foundations

Core Definition and Etymology

Fiction constitutes a category of literature or narrative wherein authors invent characters, events, and settings that lack direct correspondence to empirical reality or historical fact, primarily to explore human experience, provoke thought, or entertain.[11] Unlike non-fictional accounts, which purport to document verifiable occurrences, fiction operates through deliberate fabrication, allowing for imaginative reconstruction of possible worlds while often embedding insights into actual causal mechanisms of behavior and society.[12] This invented quality distinguishes it as a tool for simulating scenarios unbound by strict evidentiary constraints, yet its value derives from alignment with observable patterns rather than wholesale invention devoid of referential grounding.[13] The etymology of "fiction" traces to the Latin fictiō, denoting "a fashioning" or "imitating," derived from the verb fingere, "to form, shape, or devise," rooted in the Proto-Indo-European dʰeyǵʰ-, signifying "to mold or build."[14] Entering Middle English as ficcioun around 1375–1425 via Old French ficcion (attested from the 13th century, implying "invention" or "fabrication"), the term initially encompassed not only literary invention but also deception or rhetorical artifice.[15] By the late 15th century, as in William Caxton's 1483 translations, it solidified in English usage to primarily reference imagined narratives, reflecting a conceptual shift toward recognizing deliberate imaginative construction as a distinct mode of expression.[16]Distinction from Related Concepts

Fiction is distinguished from non-fiction by the absence of a commitment to literal truth or factual accuracy; non-fiction endeavors to convey verifiable events, persons, or data from the real world, whereas fiction constructs narratives through deliberate invention, unbound by empirical correspondence.[17] This demarcation hinges on authorial intent and reader expectation: non-fiction employs assertive illocutionary acts to inform or argue about reality, supported by evidence such as documentation or testimony, while fiction prescribes imaginative participation without such evidential backing.[17] For instance, a historical biography in non-fiction reconstructs documented occurrences, like the 1066 Battle of Hastings with references to primary sources, in contrast to a fictional account inventing participants or outcomes.[10] Unlike lies or deliberate deceptions, which assert falsehoods with the intent to mislead recipients into believing them as truths, fiction overtly signals its invented nature, thereby suspending the expectation of veracity and fostering authorized make-believe rather than belief.[18] Philosopher Bernard Williams defines a lie as "an assertion, the content of which one believes to be false, made with the intention that the hearer should believe it to be true," underscoring deception as the core violation; fiction evades this by framing its propositions as non-assertoric, as in novels prefixed with disclaimers like "this is a work of fiction."[18][19] Thus, while both involve false statements, fiction generates propositional attitudes of pretense—readers entertain "what if" scenarios without endorsing them as factual—whereas lies aim at epistemic deception, as seen in fabricated eyewitness accounts purporting to describe real events like the 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast panic, which some initially mistook for news due to absent fictional cues.[20][10] Fiction also separates from casual fabrications or hoaxes, which masquerade as non-fiction to perpetrate fraud, by institutional conventions in literary dissemination—such as genre labeling or paratextual indicators—that establish mutual awareness between creator and audience, eliminating deceptive intent.[20] This consent-based framework, akin to performative arts where actors do not claim real identities, ensures fiction's cognitive and emotional engagement occurs within delimited imaginative bounds, distinct from the unbounded deceit of fabrications like the 1720s forged Ossian poems, initially presented as ancient Gaelic epics to dupe scholars.[21] Empirical studies on reader processing corroborate this: audiences activate different interpretive modes for fiction, prioritizing coherence and emotional resonance over fact-checking, unlike the scrutiny applied to purported non-fiction claims.[22]Philosophical Theories of Fiction

Pretence and Make-Believe Theories

Pretence theories of fiction posit that fictional statements are issued within a mode of pretense, whereby authors and audiences engage in imagining or simulating the assertion of propositions as true, without committing to their actual truth or existential import. This approach treats fiction as a form of authorized pretense, distinct from literal assertion, deception, or belief, allowing for the non-committal exploration of scenarios. Proponents argue that such pretense explains how fictional discourse accommodates empty names and false claims without generating semantic paradoxes, as the pretense suspends standard truth-conditional semantics.[23] Make-believe theories, most systematically developed by Kendall Walton in his 1990 book Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts, refine this framework by analogizing fiction to children's games of make-believe. In Walton's account, works of fiction serve as "props"—physical or descriptive objects, such as texts or images—that generate fictional truths through "principles of generation." Participants in an "authorized game of make-believe" pretend that the prop depicts a world where certain propositions hold, yielding what is fictional via inference rules akin to those in play (e.g., if a novel describes "Sherlock Holmes lives at 221B Baker Street," it is fictional that he does, per the prop's authorization). This prop-oriented structure extends beyond literature to visual arts and theater, emphasizing communal, rule-governed imagination rather than private mental imagery.[24][25] These theories address the paradox of fiction—how audiences experience genuine emotions toward nonexistent entities—by distinguishing quasi-emotions or make-believe attitudes from full-fledged ones. For instance, fear of a fictional monster is not belief-based terror but a simulated response within the game, calibrated to the prop's prescriptions, preserving emotional engagement without requiring erroneous beliefs. Walton illustrates this with examples like a child pretending a mud pile is a cake, where affective responses arise from the game's prescriptions, not reality. Critics, however, contend that reliance on imported real-world background knowledge (e.g., physics or history presupposed in sci-fi) strains the pretense mechanism, as such imports blur the boundary between fictional and literal truths, potentially requiring ad hoc adjustments to generation principles.[26][27] Ontologically, both variants deny the existence of fictional entities like Sherlock Holmes, treating references to them as within the scope of pretense rather than denoting abstract objects or possibilia. This avoids commitment to Meinongian nonexistents or Kripkean causal chains for fictional names, aligning with a nominalist metaphysics where fiction's reality is pragmatic and activity-based, not referential. Empirical support draws from developmental psychology, noting children's prop-use in play mirrors adult fiction consumption, though skeptics argue the analogy overemphasizes ludicity at the expense of fiction's cognitive or evaluative dimensions, such as moral reasoning from narratives.[28][29]Truth in Fiction and Cognitive Value

In philosophical discussions of fiction, "truth in fiction" refers to propositions that hold within the imagined world prescribed by a fictional work, distinct from real-world truth. According to Kendall Walton's make-believe theory, such truths arise from authorized games of make-believe, where representational props (like narrative descriptions) generate fictional realities via principles of generation, allowing statements like "Sherlock Holmes lives on Baker Street" to be fictional truths without asserting literal existence.[30] This framework contrasts with earlier views, such as David Lewis's reality principle, which posits that truths in fiction align with real-world possibilities unless contradicted by the work, though critics argue it overemphasizes empirical realism at the expense of imaginative license.[31] Fictional truths thus enable internal consistency and narrative coherence but do not inherently transfer as empirical knowledge. The cognitive value of fiction pertains to whether engaging with these fictional truths yields genuine understanding or epistemic benefits about reality. Cognitivist philosophers, such as those advocating simulation theories, contend that fiction fosters mental simulation of human behaviors, enhancing theory of mind—the ability to attribute mental states to others—through immersive narratives that model causal social dynamics.[32] Empirical studies support modest effects: a 2013 experiment found that reading literary fiction for brief periods improved performance on false-belief tasks measuring theory of mind, outperforming nonfiction readers, though effects were small and short-lived.[7] Meta-analyses of longitudinal data indicate that habitual fiction readers exhibit slightly better verbal skills, empathy, and social cognition compared to non-readers, with correlations persisting after controlling for demographics, but causation remains uncertain due to self-selection biases in reading habits.[33] Skeptics challenge fiction's epistemic standing, arguing it provides imaginative insight rather than justified true belief or propositional knowledge, as fictional scenarios lack verifiable warrant and may propagate biases or falsehoods under the guise of exploration.[34] For instance, while fiction can illuminate causal patterns in human psychology—such as self-deception in Dostoevsky's characters mirroring real cognitive dissonances—overreliance on it risks conflating emotional resonance with factual accuracy, especially when narratives prioritize dramatic effect over empirical fidelity. Anti-cognitivists like Noël Carroll emphasize entertainment over education, noting that any cognitive gains stem more from reflective analysis than passive consumption. Empirical caveats reinforce this: benefits accrue primarily to those with high baseline cognitive abilities, and no large-scale studies demonstrate transformative knowledge acquisition from fiction alone, underscoring its auxiliary role to direct evidence.[35] Thus, fiction's value lies in probing possibilities and refining causal intuitions, but claims of profound epistemic import require substantiation beyond anecdotal or correlational data.Ontological Status of Fictional Entities

Fictional entities, such as characters like Sherlock Holmes or objects like his violin, prompt philosophical inquiry into their mode of being, particularly whether they possess existence independent of human imagination or linguistic description. Realist theories affirm that such entities exist in some ontological domain, while antirealist views maintain they do not, treating discourse about them as non-committal pretense or paraphrase. This debate hinges on ontological commitment: sentences like "Sherlock Holmes lives at 221B Baker Street" are true in fiction but false literally, raising questions about reference and truth conditions.[36] One prominent realist approach draws from Alexius Meinong's theory of objects, positing that fictional entities are incomplete, subsistent objects that lack actual existence but nonetheless possess properties determined by the fiction. Meinong argued in Über Gegenstandstheorie (1904) that intentional objects, including fictions, have a "so-being" (Sosein) independent of existence, allowing statements about nonexistents to be informative without paradox. This view accommodates negative existentials like "The present king of France is bald" by treating the referent as a subsisting but nonexistent entity, though critics contend it proliferates an ontologically extravagant domain of unreal objects.[37] Contemporary fictional realism, as defended by Peter van Inwagen, holds that fictional characters exist as abstract entities, akin to numbers or universals, but are not reducible to texts, sets of properties, or cultural practices. In "Existence, Ontological Commitment, and Fictional Entities" (2003), van Inwagen contends that paraphrasing away apparent references to ficta—e.g., claiming "Holmes" denotes nothing—fails to capture the intuitive truth of fictional narratives, committing ontology to their reality while denying them spatiotemporal location or causal powers. Proponents like Amie Thomasson extend this by viewing ficta as created abstract artifacts, dependent on authorial acts yet mind-independent once instituted, analogous to social entities like corporations.[38] Antirealist positions reject commitment to fictional entities' existence, often invoking pretense or make-believe. Kendall Walton's theory in Mimesis as Make-Believe (1990) analyzes fiction as a game of make-believe authorized by props (e.g., novels or props), where fictional truths arise from imagined participation rather than literal reference: it is fictional that Holmes deduces crimes, but no entity exists to instantiate this. Walton's framework explains emotional responses to fiction without ontological cost, as beliefs remain about imaginings, not real objects, though it faces challenges in accounting for cross-fictional identity, like Holmes appearing in multiple works.[24] Possibilist variants of realism, influenced by David Lewis, locate fictional entities in concrete possible worlds where the fiction's propositions hold maximally, ensuring they exist robustly but contingently outside our world. This preserves truth in fiction via modal operators—"In some world, Holmes exists and investigates"—but incurs commitments to an infinite plurality of worlds, which antirealists like Walton deem unnecessary for explanatory purposes. Empirical considerations, such as neuroscience showing imagined entities activate similar brain regions as real ones without positing dual existences, support antirealism by grounding fiction in cognitive simulation rather than ontology.[39]Fiction's Relationship to Reality

Fiction Versus Non-Fiction

Fiction constitutes literary works that depict invented narratives, characters, and events derived from the author's imagination rather than from documented reality.[40] These elements are not presented as assertions about actual occurrences but as imaginative constructs designed to engage readers through storytelling.[41] Non-fiction, by comparison, encompasses texts that purport to recount verifiable facts, historical events, or empirical observations, relying on evidence such as documents, eyewitness accounts, or data to support claims.[41] The classification hinges primarily on the author's intent and the work's truth commitments: fiction suspends demands for factual accuracy to prioritize narrative coherence and emotional resonance, while non-fiction submits to standards of verifiability and correspondence to external reality.[42] This demarcation manifests structurally as well. Fiction typically employs narrative techniques like plot progression, character arcs, and descriptive embellishment to simulate causality and human experience, often in forms such as novels or short stories.[43] Non-fiction, conversely, favors expository organization—such as chronological sequences, cause-and-effect analyses, or comparative frameworks—to convey information directly, as seen in biographies, histories, or scientific reports.[44] Empirical studies on reading comprehension highlight these differences: exposure to fiction enhances inferential and empathetic processing, whereas non-fiction bolsters factual recall and analytical skills, reflecting their divergent cognitive demands.[43] Philosophically, the divide implicates metaphysical assumptions about representation. Fiction aligns with "appearance" or simulated worlds, where descriptive statements invite make-believe without ontological commitment to their existence, allowing exploration of possibilities unbound by empirical constraints.[45] Non-fiction aligns with "reality," advancing propositions testable against observable evidence, though lapses in rigor—such as selective sourcing or interpretive bias—can undermine its factual status without reclassifying the work.[45] Borderline cases, like creative non-fiction or historical novels, test these criteria: the former retains non-fiction status if grounded in research despite stylistic flair, while the latter shifts to fiction upon introducing unverifiable inventions.[17] Despite potential for fiction to illuminate causal patterns in human behavior through analogy, non-fiction's direct evidentiary basis renders it the standard for historical or scientific truth-seeking, provided sources withstand scrutiny for ideological distortions prevalent in certain institutional outputs.[22]Realistic Versus Speculative Fiction

Realistic fiction refers to narratives that portray events, characters, and settings in a manner consistent with everyday human experience, adhering to the constraints of known physical laws, social norms, and historical plausibility without incorporating supernatural, technological, or otherwise impossible elements. These stories emphasize verisimilitude, drawing on observable realities to depict believable conflicts such as interpersonal relationships, personal growth, or societal issues, often set in the present or recent past.[46][47] The genre's focus on mimetic representation allows for explorations of psychological depth and ethical quandaries grounded in causal chains observable in real life, such as economic pressures influencing family dynamics or cultural expectations shaping individual choices.[48] Speculative fiction, by contrast, comprises an umbrella category of narratives that deliberately diverge from empirical reality by positing "what if" premises, including advanced scientific innovations, magical phenomena, alternate timelines, or dystopian extrapolations of current trends. Originating as a term in Robert A. Heinlein's 1947 correspondence critiquing science fiction's limitations, it evolved to encompass subgenres like science fiction, fantasy, and horror, enabling authors to test hypothetical causal outcomes—such as the societal impacts of interstellar travel or omnipotent artifacts—that empirical observation cannot verify.[49][50] This approach facilitates causal reasoning about untested variables, revealing potential truths about human behavior under altered conditions, though it risks conflating invention with prediction absent rigorous extrapolation from first principles.[51] The core divergence between the two lies in their fidelity to verifiability: realistic fiction constrains invention to scenarios replicable in principle within known reality, prioritizing emotional authenticity and social commentary derived from mimetic fidelity, as seen in works examining mundane adversities like illness or ambition without narrative contrivances. Speculative fiction, however, liberates storytelling from such bounds to interrogate broader existential or systemic possibilities, often employing estrangement to underscore real-world assumptions by juxtaposing them against fabricated anomalies, thereby probing causal mechanisms like technological determinism or power hierarchies in ways realistic modes cannot.[52][53] While realistic fiction may claim greater immediacy in reflecting lived truths, speculative variants offer empirical advantages in modeling low-probability events, such as pandemics amplified by policy failures, through narrative simulation rather than direct observation.[54] This distinction underscores fiction's dual role in both mirroring and extending causal realism, with each mode's evidentiary value hinging on the author's fidelity to underlying principles over mere invention.Fictionalization and Historical Accuracy

Fictionalization refers to the incorporation of invented elements, such as fabricated dialogues, composite characters, or altered sequences of events, into narratives drawn from historical contexts to achieve narrative coherence or emotional resonance.[55] This technique acknowledges gaps in the historical record, where primary sources like documents or eyewitness accounts often provide incomplete or ambiguous data, necessitating imaginative supplementation.[56] In contrast, historical accuracy demands fidelity to verifiable facts, including specific dates, causal sequences, and documented actions of real figures, as corroborated by multiple independent sources.[57] The debate over fictionalization versus accuracy centers on the trade-offs between empirical precision and interpretive depth. Aristotle, in his Poetics (circa 335 BCE), posited that poetic forms, by depicting probable universals—enduring patterns of human behavior—hold greater philosophical import than history's recounting of particulars, which merely chronicles what occurred without generalizing causal principles.[58] Modern scholars echo this by arguing that historical fiction can humanize abstract events through plausible reconstructions, fostering understanding of social dynamics or individual agency that fragmented records obscure.[56] However, excessive dramatic license risks distorting causal realities; for instance, prioritizing emotional arcs over evidence-based timelines may imply motivations unsupported by artifacts or chronicles, leading audiences to internalize invented narratives as factual.[59] Critics highlight the potential for fictionalization to propagate misconceptions, especially in popular media where interpretive inventions blend seamlessly with facts, eroding distinctions between evidence and speculation.[57] Empirical studies of reader reception indicate that vivid fictional details often overshadow verified history, complicating efforts to discern truth amid narrative allure.[56] Proponents counter that authenticity—evoking the era's material and cultural texture without literal replication—can convey causal realism more effectively than exhaustive fact-lists, as long as authors employ techniques like author's notes to delineate inventions.[56] Effective practice involves "keyhole" perspectives on ordinary lives amid documented upheavals, such as witch hunts or migrations, balancing researched customs (e.g., period attire, economic pressures) with fictional interiors to avoid overwhelming the plot.[56] Ultimately, while fictionalization enriches engagement, its truth-value hinges on subordination to evidentiary constraints, lest it undermine the causal accountability central to historical inquiry.[57]Historical Development

Ancient Origins and Classical Forms

The earliest surviving works of fiction emerge from ancient Mesopotamia, where the Epic of Gilgamesh, dating to approximately 2100 BCE in its initial Sumerian versions and evolving through Akkadian recensions by the 18th century BCE, combines quasi-historical kingship with invented quests, divine interactions, and moral explorations of mortality.[60] This cuneiform epic, spanning 12 tablets in its standard Babylonian form from around 1200 BCE, employs narrative techniques like episodic structure and character arcs to depict Gilgamesh's transformation from tyrant to sage, marking a foundational shift toward sustained imaginative storytelling over pure chronicle or ritual hymn.[61] In parallel, ancient Egyptian literature produced prose narratives such as the Tale of Sinuhe, composed during the 12th Dynasty around 1875–1840 BCE, which recounts a courtier's self-imposed exile to Canaan, his rise among foreign tribes, and repatriation under pharaonic pardon.[62] This hieratic text, preserved on multiple papyri including the Berlin Papyrus from the Middle Kingdom, uses first-person introspection, dramatic reversals, and symbolic geography to probe themes of exile and divine favor, distinguishing itself from administrative records by prioritizing psychological depth and invented dialogue over verifiable events.[63] Hellenic contributions to classical fiction centered on epic verse, with Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, orally composed and fixed in writing by the late 8th century BCE, weaving legendary Trojan War motifs into expansive tales of wrath, cunning, and homecoming.[64] The Iliad, focusing on Achilles' rage over 24 books, integrates anthropomorphic gods, heroic speeches, and battlefield realism drawn from Bronze Age echoes but amplified by poetic invention, while the Odyssey innovates with embedded tales, monstrous encounters, and tests of identity to resolve Odysseus's decade-long voyage.[65] These works, transmitted via Ionian dialect and performance tradition, established conventions like in medias res plotting and divine machinery that influenced subsequent Western narrative forms. Roman classical fiction advanced toward prose experimentation, exemplified by Gaius Petronius's Satyricon in the mid-1st century CE under Nero, a fragmented picaresque novel blending verse inserts with satirical vignettes of lowlife rogues, banquets, and impostures.[66] Surviving in partial manuscripts from the 9th century onward, it deploys vernacular dialogue, social caricature, and episodic misadventures—such as the Cena Trimalchionis dinner scene—to critique imperial excess, representing an early departure from epic grandeur toward novelistic realism and Menippean hybridity.[67] Earlier Latin efforts, like Apuleius's Metamorphoses (late 2nd century CE), further refined these elements with framed tales of magic and moral ascent, though the genre's roots in Hellenistic romances underscore fiction's evolution from mythic elaboration to self-aware invention.Medieval to Enlightenment Evolution

In the medieval period, fiction primarily manifested through verse narratives such as epics and chivalric romances, which emphasized heroic deeds, courtly love, and moral allegories often intertwined with Christian themes.[68] These works, including the anonymous Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (late 14th century) and Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (printed 1485), portrayed idealized knights undertaking quests fraught with supernatural elements and tests of honor, reflecting feudal values and oral storytelling traditions adapted to written form.[69] Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (c. 1387–1400), a collection of prose and verse stories told by pilgrims, introduced diverse social satire and character-driven narratives in Middle English, marking a shift toward more secular, observational fiction while still rooted in estate-based society.[70] The Renaissance, spanning roughly the 14th to 17th centuries, evolved fiction through humanist revival of classical antiquity, prioritizing individual agency, vernacular languages, and psychological depth over medieval didacticism.[71] Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote (Part I, 1605; Part II, 1615) satirized chivalric romances by depicting a delusional knight's misadventures, pioneering the modern novel's self-aware narrative structure and exploration of illusion versus reality in prose.[69] In England, William Shakespeare's plays (c. 1590–1613), such as Hamlet (c. 1600), blended tragic fiction with introspective soliloquies, emphasizing human flaws and ambition, while the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1440) facilitated wider dissemination of these texts, fostering a burgeoning reading public.[72] By the Enlightenment (17th–18th centuries), fiction transitioned to prose novels grounded in empirical realism and rational individualism, influenced by scientific advancements and middle-class expansion.[73] Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719) presented a first-person survival narrative drawing from castaway accounts, embodying Puritan self-reliance and economic individualism as causal drivers of plot.[74] Samuel Richardson's Pamela (1740), an epistolary novel, innovated by focusing on a servant's moral resistance to seduction, prioritizing psychological interiority and domestic virtue.[75] Henry Fielding's Tom Jones (1749) countered with ironic omniscience, critiquing social hypocrisy through picaresque adventures, solidifying the novel's form as a vehicle for causal analysis of human behavior amid Enlightenment emphasis on reason over fantasy.[76] This era's novels, produced amid rising literacy rates exceeding 50% in urban England by 1750, democratized fiction beyond elite courts, prioritizing verifiable particulars over symbolic allegory.[77]Modern Industrialization and Mass Production

The advent of mechanized printing during the Industrial Revolution transformed fiction production by enabling rapid, low-cost replication of texts. Steam-powered presses, introduced in the early 19th century, supplanted manual operations, allowing output rates to increase from hundreds to thousands of impressions per hour.[78] Concurrent advances in papermaking, including the use of wood pulp introduced in the 1840s, reduced material costs by over 80% compared to rag-based paper.[79] These innovations lowered book prices dramatically, from several shillings to mere pennies per installment, broadening fiction's reach beyond affluent readers.[78] Serialization emerged as a key adaptation to mass production, with novels released in affordable parts via newspapers and magazines to sustain reader engagement and revenue. In Britain, Charles Dickens serialized The Pickwick Papers starting in 1836, achieving sales of 40,000 copies per issue by 1837 through this method. Rising literacy rates, driven by compulsory education acts like Britain's 1870 Elementary Education Act, expanded the audience for such works among the working classes.[80] This format not only offset production risks for publishers but also influenced narrative structures, favoring episodic plots suited to weekly or monthly releases.[81] In the United States, dime novels exemplified industrialized fiction's commercialization, debuting in 1860 with Erastus Beadle's Malaeska, the Indian Wife of the White Hunter, priced at ten cents due to high-volume printing on cheap paper.[82] By the 1870s, firms like Beadle and Adams produced millions of copies annually, leveraging rotary presses and railroads for national distribution of adventure tales featuring figures like Buffalo Bill Cody.[82] These pocket-sized paperbacks targeted urban laborers and youth, fostering genres such as Westerns and detective stories while standardizing content through formulaic "fiction factories."[82] The late 19th century saw further escalation with the Linotype machine in 1886, which automated typesetting and boosted press speeds to 6,000 lines per hour, paving the way for pulp magazines in the 1890s.[83] Titles like The Argosy (launched 1882) printed on acidic wood-pulp paper, enabling monthly issues of sensational fiction at five cents each and reaching circulations exceeding 500,000 by the 1920s.[84] This era's mass production commodified fiction, prioritizing volume over durability—pulp paper yellowed quickly—and emphasized escapist narratives amid urbanization and factory labor.[85] Overall, these shifts causalized fiction's evolution from artisanal craft to industrial product, with empirical output metrics showing U.S. book titles rising from 1,000 annually in 1820 to over 4,000 by 1880, directly tied to technological efficiencies rather than mere demand surges.[86] While enhancing accessibility, the model incentivized sensationalism over depth, as publishers optimized for repeat sales in a competitive marketplace.[87]Postmodern and Contemporary Shifts

Postmodern fiction emerged in the mid-20th century as a reaction against modernist assumptions of coherence and objective truth, emphasizing instead fragmentation, irony, and metafictional self-awareness.[88] Key characteristics included non-linear narratives, intertextuality, and the blending of high and low cultural elements, often challenging grand historical or ideological narratives.[89] Works such as Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow (1973), with its encyclopedic scope and paranoid conspiracies, and Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), employing time-travel motifs to undermine linear war narratives, exemplified this shift toward playful skepticism of reality's stability.[88] By the 1990s, fiction transitioned into contemporary forms amid globalization and technological disruption, prioritizing hybrid genres and market-driven accessibility over postmodern experimentation.[90] Speculative fiction surged, incorporating science fiction, fantasy, and dystopian elements to address empirical concerns like technological acceleration and environmental collapse, with subgenres evolving to reflect post-Cold War anxieties.[90] This rise paralleled a quantitative expansion: available book titles grew from approximately 500,000 in 1990 to over 20 million by the 2020s, driven by digital tools enabling rapid production.[91] Digital publishing fundamentally altered fiction's dissemination and creation, with Amazon's Kindle launch in 2007 accelerating e-book adoption and self-publishing proliferation.[92] Self-published fiction dominated ISBN registrations, accounting for 335,428 titles in a recent year, outpacing traditional outputs and allowing authors to bypass gatekeepers, though this flooded markets with low-barrier content of varying quality.[92] Globalization facilitated multicultural narratives, yet empirical data on sales indicate genre fiction—speculative and romance—outperformed experimental literary works, reflecting reader preferences for escapist or cautionary tales amid real-world uncertainties like climate data projections and AI advancements.[90] Contemporary shifts also include the emergence of interactive and web-based fiction, where authors leverage platforms for serialized, reader-influenced stories, blurring lines between creator and consumer.[93] This participatory model, rooted in 1990s electronic literature experiments, expanded with broadband access, enabling global co-creation but raising causal questions about diluted authorial intent versus democratized expression. Surveys of self-published authors show nearly half earning over $20,000 annually by 2023, underscoring economic viability for niche, data-driven genre targeting over broad postmodern abstraction.[94]Structural Elements of Fiction

Narrative and Plot Construction

Narrative in fiction refers to the method and manner by which a story is conveyed to the audience, encompassing choices in perspective, voice, tense, and temporal ordering of events.[95] Plot, by contrast, constitutes the structured sequence of events linked by causality, where actions and consequences drive progression rather than mere chronology.[96] This distinction, articulated by E.M. Forster in his 1927 lectures compiled as Aspects of the Novel, differentiates a mere story—"The king died and then the queen died"—from a plot—"The king died and then the queen died of grief"—emphasizing causal connections that imbue events with inevitability and meaning.[97] Effective plot construction thus prioritizes logical chains of cause and effect, mirroring causal realism in human experience, as arbitrary sequences fail to sustain engagement or coherence. In ancient theory, Aristotle's Poetics (circa 335 BCE) elevates plot (mythos) as the "soul" of tragedy and the foremost element of fiction, surpassing character or diction in importance because it imitates purposeful action with unity: a complete whole with beginning, middle, and end, featuring reversal (peripeteia) and recognition (anagnorisis) to evoke pity and fear.[98] This framework demands complication (events building tension) and resolution through necessity rather than probability alone, ensuring the plot's events are neither episodic nor contrived but organically derived from character choices and circumstances.[99] Empirical support for such causality emerges from psychological research, where narratives with strong problem-solving arcs and protagonist reactions align with cognitive processing, enhancing comprehension and emotional resonance by simulating real-world decision-making under conflict.[100] Classical models evolved into Freytag's Pyramid, proposed by Gustav Freytag in Die Technik des Dramas (1863), which diagrams plot as an ascending and descending structure: exposition introduces characters and stakes; rising action builds conflicts through complications; climax delivers the turning point of highest tension; falling action depicts consequences; and denouement resolves loose ends.[101] Adapted from Aristotelian analysis of Sophoclean tragedy, this five-part form facilitates dramatic tension via escalating stakes, though it assumes a tragic arc and may constrain non-linear or open-ended modern plots.[102] In screenwriting, Syd Field's three-act structure, outlined in Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting (1979), refines this for contemporary media: Act One (setup, ~25% of length) establishes world and inciting incident; Act Two (confrontation, ~50%) amplifies obstacles via plot points; Act Three (resolution, ~25%) culminates in crisis and denouement.[103] These paradigms persist due to their alignment with attentional and memory mechanisms, as studies show structured plots with repetition-break patterns—initial stability disrupted by novelty—increase idea retention and perceived value in narratives.[104] Construction techniques emphasize conflict as the engine of plot: internal (psychological) or external (interpersonal/environmental) forces propel change, with foreshadowing and withholding information to manipulate pacing and suspense.[105] Nonlinear narratives, such as flashbacks or multiple viewpoints, reorder events for emphasis but must preserve underlying causality to avoid confusion, as evidenced by reader disengagement in plots lacking clear motivations.[106] Psychological efficacy derives from embodied simulation, where plot arcs evoke mirror neuron activation akin to real experiences, fostering immersion; deviations, like deus ex machina resolutions, undermine this by violating causal expectations, reducing narrative transportation.[107] Thus, robust plot construction demands rigorous causal mapping from inception, tested against first-principles logic to ensure events follow plausibly from premises rather than authorial fiat.Character Development and Psychology

Character development in fiction entails the deliberate construction of protagonists, antagonists, and supporting figures with internal consistency, motivations rooted in psychological realism, and trajectories of change or stasis that align with causal human behavior. Authors achieve depth by integrating empirical insights from psychology, such as how early formative wounds shape core fears and defense mechanisms, enabling characters to respond authentically to narrative pressures.[108][109] This approach contrasts with superficial portrayals, prioritizing causal links between past experiences and present actions over contrived plot devices. Psychological realism, as delineated in literary analysis, emphasizes the portrayal of inner monologues and subjective motivations to mirror verifiable human cognition, fostering reader immersion through relatable mental processes.[110] Techniques for realism include mapping characters' attachment styles—secure, anxious, avoidant, or disorganized—which dictate interpersonal conflicts and relational arcs, grounded in attachment theory's observation that early caregiver interactions predict adult bonding patterns.[108] Flaws and limiting beliefs, derived from cognitive psychology, add complexity; for instance, a protagonist's irrational self-sabotage may stem from unexamined cognitive distortions, evolving via exposure to contradictory evidence in the plot.[111] Jungian archetypes provide a framework for universal resonance, with figures like the Hero embodying innate patterns of transformation through trials, or the Shadow representing repressed instincts that surface in conflict, enhancing psychological verisimilitude without reducing characters to stereotypes.[112] These elements ensure characters exhibit causal realism, where behaviors arise from integrated psyche rather than authorial fiat. Character arcs, the psychological progression from initial state to resolution, hinge on internal conflict resolution, such as overcoming core desires clashing with reality, as seen in arcs where trauma processing leads to adaptive growth or tragic entrenchment.[113] Empirical psychological lenses, including vulnerability assessment and identity formation, underpin believable evolution; characters who process events through distorted lenses fail to change, reflecting real stasis in maladaptive personalities.[114] In practice, writers simulate inner dialogues via method-acting immersion to capture authentic thought patterns, avoiding idealized portrayals that defy observed human variability.[109] This method yields flawed, multifaceted agents whose decisions propel the narrative, underscoring fiction's capacity to model causal psychological dynamics.[115]Setting, Theme, and Symbolism

The setting in fiction encompasses the time period, geographical location, and broader environmental or social context in which the narrative events occur, serving as the foundational backdrop that shapes character motivations and plot progression. [116] By establishing parameters for action—such as historical eras constraining technological possibilities or isolated locales amplifying tension—setting influences causal chains in the story, often dictating feasible conflicts and resolutions grounded in realistic or speculative constraints. [117] In certain narratives, setting extends beyond mere locale to embody atmospheric elements like weather or cultural norms, which can mirror internal character states or propel thematic exploration, as seen in works where physical isolation reinforces psychological isolation. [118] Themes in fiction represent the central, unifying insights or propositions about human experience, society, or existence that arise from the narrative's conflicts and resolutions, rather than mere plot summaries. [119] These emerge implicitly through recurring patterns in character decisions and outcomes, often addressing causal realities such as the consequences of ambition or the fragility of social order, and they unify disparate elements into a coherent commentary without dictating moral prescriptions. [120] Authors derive themes from empirical observations of behavior or historical precedents, embedding them to provoke reader reflection on verifiable patterns, such as power dynamics in hierarchical structures, thereby distinguishing fiction's analytical depth from superficial entertainment. [121] Symbolism functions as a narrative technique wherein concrete objects, actions, or motifs represent abstract ideas, emotions, or broader themes, allowing layered interpretation without explicit exposition. [122] Recurring symbols—such as a recurring color evoking danger or a natural element signifying transience—accumulate meaning through context and repetition, enhancing thematic density by linking literal events to underlying causal principles, like decay mirroring moral entropy. [123] In fiction, symbolism integrates with setting and theme by transforming environmental details into interpretive devices; for instance, a confined space might symbolize entrapment, reinforcing themes of determinism while grounding them in observable psychological responses to spatial limits. [124] This method demands authorial precision to avoid ambiguity, as overreliance risks obscuring narrative clarity, yet it enables concise conveyance of complex realities when tied to empirical motifs. [125]Forms and Mediums of Fiction

Literary Classifications by Length and Style

Fiction is commonly classified by length into categories that reflect the scope and complexity of narrative development, with word counts serving as approximate benchmarks established by literary organizations and publishing standards. These distinctions originated in the early 20th century, particularly through awards like the Hugo and Nebula, administered by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA), which formalized ranges to differentiate eligibility for recognition. Shorter forms prioritize conciseness and intensity, while longer ones allow for expansive world-building and subplots. Variations exist across publishers, but SFWA guidelines—short story under 7,500 words, novelette 7,500–17,500 words, novella 17,500–40,000 words, and novel over 40,000 words—provide a widely referenced framework.[126]| Category | Approximate Word Count Range | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Flash Fiction | Under 1,000 (often 300–1,000) | Ultra-concise narratives focusing on a single moment or twist; emphasizes economy of language and surprise endings, as seen in works by Lydia Davis.[127] |

| Short Story | 1,000–7,500 | Self-contained tales with limited characters and settings; prioritizes thematic depth over breadth, exemplified by Edgar Allan Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart" (2,100 words).[126] |

| Novelette | 7,500–17,500 | Bridges short story and novella; allows moderate plot development, common in speculative fiction like Ursula K. Le Guin's "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" (approximately 8,000 words).[128] |

| Novella | 17,500–40,000 | Extended form enabling deeper character arcs than short stories but tighter than novels; notable examples include Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness" (38,000 words) and George Orwell's "Animal Farm" (30,000 words).[129] |

| Novel | Over 40,000 (typically 50,000–110,000) | Comprehensive narratives with multiple arcs, subplots, and themes; epic novels like Leo Tolstoy's "War and Peace" exceed 500,000 words, while standard commercial novels average 80,000–100,000.[130] |

Prose Versus Scripted and Visual Formats

Prose fiction, typically presented in novel or short story form, relies on descriptive language to convey internal monologues, expansive settings, and subtle psychological nuances that demand active reader imagination.[134] In contrast, scripted formats such as plays and screenplays prioritize dialogue and concise action lines, designed for live performance or filming, where narrative exposition must be minimized to suit actors' delivery and directorial interpretation.[135] Visual formats, including films, television series, and animations, translate these scripts into a multimedia experience emphasizing "show, don't tell" through cinematography, editing, sound design, and performer expressions, often accelerating pace to fit runtime constraints of 90-180 minutes.[134]A primary distinction lies in depth of character and plot: prose allows intricate subplots, backstory, and sensory details like odors or abstract thoughts that visual media struggles to depict without exposition dumps, which disrupt pacing.[136] [137] For instance, adaptations like the Harry Potter series from J.K. Rowling's novels to films often condense complex internal motivations into visual cues, sacrificing nuance for action sequences to maintain audience engagement.[138] Scripted formats bridge this by focusing on verbal interplay, as in theatrical works like Shakespeare's plays, but remain limited by performance logistics compared to prose's unlimited scope.[139] Cognitively, reading prose activates broader brain networks for visualization and empathy simulation, enhancing connectivity in regions linked to social understanding, whereas viewing films engages fewer areas with less imaginative effort, though both foster theory-of-mind skills.[140] [141] [142] Visual media excels in immediacy and emotional amplification via music and cuts, appealing to broader audiences but risking shallower processing; prose, by requiring sustained attention, builds deeper immersion over time.[143] Economically, visual fiction dominates revenue: global cinema admissions generated $46.4 billion in 2023, with book-adapted films averaging 53% higher box office than originals, while publishing revenue reached approximately $144 billion in 2024, including non-fiction.[144] [145] [146] This disparity reflects visual formats' scalability through theaters and streaming, versus prose's lower production costs but reliance on individual consumption. Challenges in cross-format shifts, such as omitting internal depth in screen adaptations, highlight causal trade-offs: visual efficiency prioritizes spectacle over subtlety, potentially altering thematic fidelity.[134][147]