Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cyclomatic complexity

View on WikipediaCyclomatic complexity is a software metric used to indicate the complexity of a program. It is a quantitative measure of the number of linearly independent paths through a program's source code. It was developed by Thomas J. McCabe, Sr. in 1976.

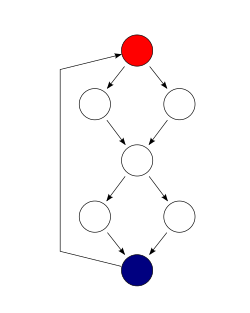

Cyclomatic complexity is computed using the control-flow graph of the program. The nodes of the graph correspond to indivisible groups of commands of a program, and a directed edge connects two nodes if the second command might be executed immediately after the first command. Cyclomatic complexity may also be applied to individual functions, modules, methods, or classes within a program.

One testing strategy, called basis path testing by McCabe who first proposed it, is to test each linearly independent path through the program. In this case, the number of test cases will equal the cyclomatic complexity of the program.[1]

Description

[edit]Definition

[edit]

There are multiple ways to define cyclomatic complexity of a section of source code. One common way is the number of linearly independent paths within it. A set of paths is linearly independent if the edge set of any path in is not the union of edge sets of the paths in some subset of . If the source code contained no control flow statements (conditionals or decision points) the complexity would be 1, since there would be only a single path through the code. If the code had one single-condition IF statement, there would be two paths through the code: one where the IF statement is TRUE and another one where it is FALSE. Here, the complexity would be 2. Two nested single-condition IFs, or one IF with two conditions, would produce a complexity of 3.

Another way to define the cyclomatic complexity of a program is to look at its control-flow graph, a directed graph containing the basic blocks of the program, with an edge between two basic blocks if control may pass from the first to the second. The complexity M is then defined as[2]

where

- E = the number of edges of the graph.

- N = the number of nodes of the graph.

- P = the number of connected components.

An alternative formulation of this, as originally proposed, is to use a graph in which each exit point is connected back to the entry point. In this case, the graph is strongly connected. Here, the cyclomatic complexity of the program is equal to the cyclomatic number of its graph (also known as the first Betti number), which is defined as[2]

This may be seen as calculating the number of linearly independent cycles that exist in the graph: those cycles that do not contain other cycles within themselves. Because each exit point loops back to the entry point, there is at least one such cycle for each exit point.

For a single program (or subroutine or method), P always equals 1; a simpler formula for a single subroutine is[3]

Cyclomatic complexity may be applied to several such programs or subprograms at the same time (to all of the methods in a class, for example). In these cases, P will equal the number of programs in question, and each subprogram will appear as a disconnected subset of the graph.

McCabe showed that the cyclomatic complexity of a structured program with only one entry point and one exit point is equal to the number of decision points ("if" statements or conditional loops) contained in that program plus one. This is true only for decision points counted at the lowest, machine-level instructions.[4] Decisions involving compound predicates like those found in high-level languages like IF cond1 AND cond2 THEN ... should be counted in terms of predicate variables involved. In this example, one should count two decision points because at machine level it is equivalent to IF cond1 THEN IF cond2 THEN ....[2][5]

Cyclomatic complexity may be extended to a program with multiple exit points. In this case, it is equal to where is the number of decision points in the program and s is the number of exit points.[5][6]

Interpretation

[edit]In his presentation "Software Quality Metrics to Identify Risk"[7] for the Department of Homeland Security, Tom McCabe introduced the following categorization of cyclomatic complexity:

- 1 - 10: Simple procedure, little risk

- 11 - 20: More complex, moderate risk

- 21 - 50: Complex, high risk

- > 50: Untestable code, very high risk

In algebraic topology

[edit]An even subgraph of a graph (also known as an Eulerian subgraph) is one in which every vertex is incident with an even number of edges. Such subgraphs are unions of cycles and isolated vertices. Subgraphs will be identified with their edge sets, which is equivalent to only considering those even subgraphs which contain all vertices of the full graph.

The set of all even subgraphs of a graph is closed under symmetric difference, and may thus be viewed as a vector space over GF(2). This vector space is called the cycle space of the graph. The cyclomatic number of the graph is defined as the dimension of this space. Since GF(2) has two elements and the cycle space is necessarily finite, the cyclomatic number is also equal to the 2-logarithm of the number of elements in the cycle space.

A basis for the cycle space is easily constructed by first fixing a spanning forest of the graph, and then considering the cycles formed by one edge not in the forest and the path in the forest connecting the endpoints of that edge. These cycles form a basis for the cycle space. The cyclomatic number also equals the number of edges not in a maximal spanning forest of a graph. Since the number of edges in a maximal spanning forest of a graph is equal to the number of vertices minus the number of components, the formula defines the cyclomatic number.[8]

Cyclomatic complexity can also be defined as a relative Betti number, the size of a relative homology group:

which is read as "the rank of the first homology group of the graph G relative to the terminal nodes t". This is a technical way of saying "the number of linearly independent paths through the flow graph from an entry to an exit", where:

- "linearly independent" corresponds to homology, and backtracking is not double-counted;

- "paths" corresponds to first homology (a path is a one-dimensional object); and

- "relative" means the path must begin and end at an entry (or exit) point.

This cyclomatic complexity can be calculated. It may also be computed via absolute Betti number by identifying the terminal nodes on a given component, or drawing paths connecting the exits to the entrance. The new, augmented graph obtains

It can also be computed via homotopy. If a (connected) control-flow graph is considered a one-dimensional CW complex called , the fundamental group of will be . The value of is the cyclomatic complexity. The fundamental group counts how many loops there are through the graph up to homotopy, aligning as expected.

Applications

[edit]Limiting complexity during development

[edit]One of McCabe's original applications was to limit the complexity of routines during program development. He recommended that programmers should count the complexity of the modules they are developing, and split them into smaller modules whenever the cyclomatic complexity of the module exceeded 10.[2] This practice was adopted by the NIST Structured Testing methodology, which observed that since McCabe's original publication, the figure of 10 had received substantial corroborating evidence. However, it also noted that in some circumstances it may be appropriate to relax the restriction and permit modules with a complexity as high as 15. As the methodology acknowledged that there were occasional reasons for going beyond the agreed-upon limit, it phrased its recommendation as "For each module, either limit cyclomatic complexity to [the agreed-upon limit] or provide a written explanation of why the limit was exceeded."[9]

Measuring the "structuredness" of a program

[edit]Section VI of McCabe's 1976 paper is concerned with determining what the control-flow graphs (CFGs) of non-structured programs look like in terms of their subgraphs, which McCabe identified. (For details, see structured program theorem.) McCabe concluded that section by proposing a numerical measure of how close to the structured programming ideal a given program is, i.e. its "structuredness". McCabe called the measure he devised for this purpose essential complexity.[2]

To calculate this measure, the original CFG is iteratively reduced by identifying subgraphs that have a single-entry and a single-exit point, which are then replaced by a single node. This reduction corresponds to what a human would do if they extracted a subroutine from the larger piece of code. (Nowadays such a process would fall under the umbrella term of refactoring.) McCabe's reduction method was later called condensation in some textbooks, because it was seen as a generalization of the condensation to components used in graph theory.[10] If a program is structured, then McCabe's reduction/condensation process reduces it to a single CFG node. In contrast, if the program is not structured, the iterative process will identify the irreducible part. The essential complexity measure defined by McCabe is simply the cyclomatic complexity of this irreducible graph, so it will be precisely 1 for all structured programs, but greater than one for non-structured programs.[9]: 80

Implications for software testing

[edit]Another application of cyclomatic complexity is in determining the number of test cases that are necessary to achieve thorough test coverage of a particular module.

It is useful because of two properties of the cyclomatic complexity, M, for a specific module:

- M is an upper bound for the number of test cases that are necessary to achieve a complete branch coverage.

- M is a lower bound for the number of paths through the control-flow graph (CFG). Assuming each test case takes one path, the number of cases needed to achieve path coverage is equal to the number of paths that can actually be taken. But some paths may be impossible, so although the number of paths through the CFG is clearly an upper bound on the number of test cases needed for path coverage, this latter number (of possible paths) is sometimes less than M.

All three of the above numbers may be equal: branch coverage cyclomatic complexity number of paths.

For example, consider a program that consists of two sequential if-then-else statements.

if (c1())

f1();

else

f2();

if (c2())

f3();

else

f4();

In this example, two test cases are sufficient to achieve a complete branch coverage, while four are necessary for complete path coverage. The cyclomatic complexity of the program is 3 (as the strongly connected graph for the program contains 8 edges, 7 nodes, and 1 connected component) (8 − 7 + 2).

In general, in order to fully test a module, all execution paths through the module should be exercised. This implies a module with a high complexity number requires more testing effort than a module with a lower value since the higher complexity number indicates more pathways through the code. This also implies that a module with higher complexity is more difficult to understand since the programmer must understand the different pathways and the results of those pathways.

Unfortunately, it is not always practical to test all possible paths through a program. Considering the example above, each time an additional if-then-else statement is added, the number of possible paths grows by a factor of 2. As the program grows in this fashion, it quickly reaches the point where testing all of the paths becomes impractical.

One common testing strategy, espoused for example by the NIST Structured Testing methodology, is to use the cyclomatic complexity of a module to determine the number of white-box tests that are required to obtain sufficient coverage of the module. In almost all cases, according to such a methodology, a module should have at least as many tests as its cyclomatic complexity. In most cases, this number of tests is adequate to exercise all the relevant paths of the function.[9]

As an example of a function that requires more than mere branch coverage to test accurately, reconsider the above function. However, assume that to avoid a bug occurring, any code that calls either f1() or f3() must also call the other.[a] Assuming that the results of c1() and c2() are independent, the function as presented above contains a bug. Branch coverage allows the method to be tested with just two tests, such as the following test cases:

c1()returns true andc2()returns truec1()returns false andc2()returns false

Neither of these cases exposes the bug. If, however, we use cyclomatic complexity to indicate the number of tests we require, the number increases to 3. We must therefore test one of the following paths:

c1()returns true andc2()returns falsec1()returns false andc2()returns true

Either of these tests will expose the bug.

Correlation to number of defects

[edit]Multiple studies have investigated the correlation between McCabe's cyclomatic complexity number with the frequency of defects occurring in a function or method.[11] Some studies[12] find a positive correlation between cyclomatic complexity and defects; functions and methods that have the highest complexity tend to also contain the most defects. However, the correlation between cyclomatic complexity and program size (typically measured in lines of code) has been demonstrated many times. Les Hatton has claimed[13] that complexity has the same predictive ability as lines of code. Studies that controlled for program size (i.e., comparing modules that have different complexities but similar size) are generally less conclusive, with many finding no significant correlation, while others do find correlation. Some researchers question the validity of the methods used by the studies finding no correlation.[14] Although this relation likely exists, it is not easily used in practice.[15] Since program size is not a controllable feature of commercial software, the usefulness of McCabe's number has been questioned.[11] The essence of this observation is that larger programs tend to be more complex and to have more defects. Reducing the cyclomatic complexity of code is not proven to reduce the number of errors or bugs in that code. International safety standards like ISO 26262, however, mandate coding guidelines that recommend to monitor and aim to reduce code complexity, where complexity is high additional measures including scrutiny of the more difficult verification and validation activities including testing is expected.[16]

See also

[edit]- Programming complexity

- Complexity trap

- Computer program

- Computer programming

- Control flow

- Decision-to-decision path

- Design predicates

- Essential complexity (numerical measure of "structuredness")

- Halstead complexity measures

- Software engineering

- Software testing

- Static program analysis

- Maintainability

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is a fairly common type of condition; consider the possibility that

f1allocates some resource whichf3releases.

References

[edit]- ^ A J Sobey. "Basis Path Testing".

- ^ a b c d e McCabe (December 1976). "A Complexity Measure". IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. SE-2 (4): 308–320. doi:10.1109/tse.1976.233837. S2CID 9116234.

- ^ Philip A. Laplante (25 April 2007). What Every Engineer Should Know about Software Engineering. CRC Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4200-0674-2.

- ^ Fricker, Sébastien (April 2018). "What exactly is cyclomatic complexity?". froglogic GmbH. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

To compute a graph representation of code, we can simply disassemble its assembly code and create a graph following the rules: ...

- ^ a b J. Belzer; A. Kent; A. G. Holzman; J. G. Williams (1992). Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology. CRC Press. pp. 367–368.

- ^ Harrison (October 1984). "Applying Mccabe's complexity measure to multiple-exit programs". Software: Practice and Experience. 14 (10): 1004–1007. doi:10.1002/spe.4380141009. S2CID 62422337.

- ^ Thomas McCabe Jr. (2008). "Software Quality Metrics to Identify Risk". Archived from the original on 2022-03-29.

- ^ Diestel, Reinhard (2000). Graph theory. Graduate texts in mathematics 173 (2 ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-98976-1.

- ^ a b c Arthur H. Watson; Thomas J. McCabe (1996). "Structured Testing: A Testing Methodology Using the Cyclomatic Complexity Metric" (PDF). NIST Special Publication 500-235.

- ^ Paul C. Jorgensen (2002). Software Testing: A Craftsman's Approach, Second Edition (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 150–153. ISBN 978-0-8493-0809-3.

- ^ a b Norman E Fenton; Martin Neil (1999). "A Critique of Software Defect Prediction Models" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. 25 (3): 675–689. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.548.2998. doi:10.1109/32.815326.

- ^ Schroeder, Mark (1999). "A Practical guide to object-oriented metrics". IT Professional. 1 (6): 30–36. doi:10.1109/6294.806902. S2CID 14945518.

- ^ Les Hatton (2008). "The role of empiricism in improving the reliability of future software". version 1.1.

- ^ Kan (2003). Metrics and Models in Software Quality Engineering. Addison-Wesley. pp. 316–317. ISBN 978-0-201-72915-3.

- ^ G.S. Cherf (1992). "An Investigation of the Maintenance and Support Characteristics of Commercial Software". Journal of Software Quality. 1 (3): 147–158. doi:10.1007/bf01720922. ISSN 1573-1367. S2CID 37274091.

- ^ ISO 26262-3:2011(en) Road vehicles — Functional safety — Part 3: Concept phase. International Standardization Organization.

External links

[edit]Cyclomatic complexity

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

Cyclomatic complexity is a software metric proposed by Thomas J. McCabe in 1976 to assess program complexity in structured programming.[5] This graph-theoretic measure was introduced in McCabe's seminal paper, where it is described as a tool for managing and controlling the complexity inherent in software modules.[5] At its core, cyclomatic complexity quantifies the number of linearly independent paths through a program's source code, providing a numerical indicator of the control flow's intricacy.[6] By focusing on decision structures such as branches and loops, it captures the essential elements that determine how many distinct execution trajectories a program can take.[5] The primary purpose of this metric is to evaluate the maintainability and testability of code by highlighting areas with excessive decision points that could lead to errors or difficulties in modification.[6] It serves as a basis for determining the minimum number of test cases required to achieve adequate path coverage during testing.[6] Historically, cyclomatic complexity emerged as a response to the limitations of earlier metrics like lines of code, which often failed to account for the true impact of control structures on program reliability and comprehension. McCabe's approach shifted emphasis toward the logical architecture, enabling developers to identify overly complex modules before they become problematic in maintenance phases.Mathematical Formulation

Cyclomatic complexity, denoted as , is formally defined for a control flow graph as , where represents the number of edges, the number of nodes, and the number of connected components in the graph.[5] For a typical single-procedure program represented by a strongly connected graph (where ), this simplifies to .[5] In this context, nodes correspond to blocks of sequential code that cannot be decomposed further, while edges depict transfers of control between these blocks, such as jumps, branches, or sequential flows.[5] Alternative formulations provide equivalent ways to compute without explicitly constructing the full graph. One such expression is , where is the number of predicate nodes—those containing conditional statements like if-then-else or loop conditions that introduce branching.[5] Another equivalent form is the number of decision points in the code, aligning with the count of linearly independent paths through the program.[5] This measure originates from graph theory, specifically deriving from Euler's formula for planar graphs, which states that for a connected planar graph, , where is the number of faces (regions bounded by edges, including the infinite outer face).[4] Rearranging yields , and in the context of control flow graphs embedded planarly, equals the number of faces (including the outer face), representing the number of linearly independent paths through the control flow graph and thus the minimum number of test paths needed for basis path coverage.[4][5]Computation

Control Flow Graphs

Control flow graphs provide a graphical representation of a program's control structure, modeling the sequence of executable statements and the decisions that alter execution paths. Introduced by Thomas McCabe as the foundational tool for his complexity metric, these graphs are directed and consist of nodes and edges that capture the logical flow without regard to data dependencies.[5] The construction of a control flow graph begins by partitioning the program's source code into basic blocks, which are maximal sequences of consecutive statements where control enters at the beginning and exits at the end, with no internal branches or jumps. Each basic block becomes a node in the graph, and directed edges connect these nodes to indicate possible control transfers, such as sequential progression from one block to the next, conditional branches from if-then-else constructs, or iterative paths in loops like while or do-while statements. This process ensures the graph accurately reflects all feasible execution sequences.[5][7] Key elements of the graph include the entry node, which represents the initial basic block where execution starts, and the exit node, denoting the final block leading to program termination. Decision nodes, typically those ending in branching statements like conditional tests or case switches, feature multiple outgoing edges, each corresponding to a distinct control flow outcome— for instance, true and false branches from an if condition. Loops introduce edges that return control to earlier nodes, forming cycles in the graph.[5][7] Specific rules govern graph building to handle varying code styles. For structured programming, which adheres to sequential, selective, and iterative constructs without unrestricted jumps, basic blocks are straightforwardly identified at control structure boundaries, ensuring a clean, hierarchical flow. Unstructured code, such as that employing goto statements or multiple entry points, requires inserting edges for each jump to connect non-adjacent blocks, which can complicate the graph by creating additional decision points or cycles. In all cases, compound statements like nested ifs are reduced to their constituent basic blocks before edge assignment, and sequential code without branches forms single nodes with a single incoming and outgoing edge. McCabe emphasized that this reduction to basic blocks simplifies analysis while preserving the program's logical paths.[5][7] As an illustrative example, consider a basic if-statement in pseudocode:if (condition) {

statement1;

} else {

statement2;

}

statement3;

if (condition) {

statement1;

} else {

statement2;

}

statement3;

- Node 1 (entry): The block containing the condition check (decision node).

- Edge from Node 1 to Node 2 (true branch): The block with statement1.

- Edge from Node 1 to Node 3 (false branch): The block with statement2.

- Edges from Node 2 and Node 3 to Node 4 (exit): The block with statement3.

Calculation Procedures

To compute cyclomatic complexity, the process begins with constructing a control flow graph (CFG) from the source code, where nodes represent basic blocks of sequential statements and edges represent possible control flow transfers between them.[8] Once the CFG is built, identify the total number of nodes (including entry and exit points) and the total number of edges (including those from decision points). The complexity is then calculated using the formula for a connected graph with a single entry and exit point.[9] For programs consisting of multiple modules or functions, cyclomatic complexity is typically computed separately for each module using the above method, as each represents an independent control flow structure. The overall program complexity can then be obtained by summing the individual values across all modules, providing a measure of total path independence. Static analysis tools automate this computation by parsing code to generate CFGs internally and applying the formula without manual intervention. For instance, PMD, an open-source code analyzer, includes rules that evaluate cyclomatic complexity per method and reports violations against configurable thresholds during builds or IDE integration. Similarly, SonarQube computes complexity at the function level and aggregates it for broader codebases, integrating with CI/CD pipelines to flag high-complexity areas in real-time scans. Consider the following Java code snippet as an illustrative example:public int countEvens(int limit) {

int count = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

if (i % 2 == 0) {

count++;

}

}

return count;

}

public int countEvens(int limit) {

int count = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

if (i % 2 == 0) {

count++;

}

}

return count;

}

- Node 1: Initialization (count = 0; i = 0)

- Node 2: Loop condition (i < limit)

- Node 3: Inner if condition (i % 2 == 0)

- Node 4: count++ (true branch)

- Node 5: i++ (after true or false branch)

- Node 6: return count (exit)

Interpretation

Value Meanings

Cyclomatic complexity values provide insight into the structural simplicity or intricacy of a program, directly reflecting the number of linearly independent paths through its control flow. A value of denotes a straightforward, sequential execution without any branching or decision points, characteristic of the simplest possible program structure.[5] Values ranging from 2 to 10 indicate moderate complexity, where a limited set of decision elements introduces manageable branching, facilitating comprehension and testing without overwhelming structural demands.[9] In contrast, values exceeding 10 signal elevated complexity, often associated with intricate control flows that challenge long-term maintainability and heighten the potential for structural vulnerabilities.[5] Elevated cyclomatic complexity values arise from an proliferation of execution paths, which impose greater cognitive demands on developers during comprehension, modification, and debugging activities. This multiplicity of paths can increase error proneness, as each independent route represents an opportunity for inconsistencies or oversights to manifest.[4] Several programming constructs contribute to higher cyclomatic complexity scores, including deeply nested decision statements such as if-else chains, compound conditions combining multiple logical operators (e.g., && or ||), and exception handling blocks that introduce additional control branches. These elements each increment the decision count, thereby expanding the overall path diversity.[4] Empirical analyses underscore the practical implications of these values for software reliability, revealing that modules with tend to demonstrate superior stability. In one study of production code, modules below this threshold averaged 4.6 errors per 100 source statements, while those at or above 10 averaged 21.2 errors per 100 source statements, highlighting a marked increase in defect density with rising complexity.[4]Threshold Guidelines

Thomas J. McCabe originally recommended that the cyclomatic complexity V(G) of a software module should not exceed 10, as higher values correlate with increased error rates and reduced maintainability; modules surpassing this threshold should be refactored to improve testability and reliability.[4] Some standards adopt higher limits for specific contexts. For example, NASA Procedural Requirements (NPR) 7150.2D (effective March 8, 2022) requires that safety-critical software components have a cyclomatic complexity value of 15 or lower, with any exceedances reviewed and waived with rationale to ensure testability and safety.[10] This threshold, while higher than McCabe's general recommendation, is accompanied by rigorous testing requirements such as 100% Modified Condition/Decision Coverage (MC/DC).[11] When V(G) exceeds recommended thresholds, refactoring strategies focus on decomposing complex functions into smaller, independent units to distribute decision points and lower overall complexity.[12] For instance, extracting conditional logic into helper functions reduces nesting and independent paths, enhancing modularity without altering program behavior.[12] To enforce these guidelines, cyclomatic complexity monitoring is integrated into code reviews, where reviewers flag high-V(G) modules for refactoring, and into CI/CD pipelines via static analysis tools that automatically compute and report metrics during builds.[13] This continuous integration approach prevents complexity creep and aligns development with established limits across project lifecycles.[14]Applications

Design and Development

Cyclomatic complexity serves as a foundational metric in software design, directing developers toward modular and structured programming practices that minimize the value of V(G). Introduced by Thomas McCabe, this measure quantifies the linear independence of paths in a program's control flow graph, prompting the breakdown of intricate logic into discrete, low-complexity modules to prevent excessive nesting and branching. Such design strategies align with principles of structured programming, fostering code that is inherently more comprehensible and adaptable during the creation phase.[5] In long-term software projects, maintaining low cyclomatic complexity yields tangible benefits for upkeep, as evidenced by empirical studies linking reduced V(G) to streamlined updates and diminished bug introduction risks. Research on maintenance productivity reveals that higher complexity densities inversely correlate with efficiency, with teams expending less effort on modifications in simpler modules compared to their more convoluted counterparts. This correlation underscores the metric's value in sustaining project viability over extended lifecycles. Within development workflows, cyclomatic complexity integrates as a proactive indicator in design reviews, enabling early detection and mitigation of potential complexity spikes. Practitioners employ it to enforce guidelines, such as capping module V(G) at 10, ensuring collaborative scrutiny aligns code evolution with maintainability goals from inception. For example, in guided review processes, complexity thresholds flag revisions needed to preserve structural simplicity.[15]Testing Strategies

Cyclomatic complexity serves as the basis for estimating the minimum number of test cases required to achieve full path coverage in a program's control flow graph, where the value V(G) directly equals the number of linearly independent paths that must be tested. This metric, introduced by Thomas McCabe, ensures that testing efforts target the program's logical structure to verify all decision outcomes without redundancy.[8] A primary strategy leveraging cyclomatic complexity is basis path testing, which involves identifying and executing a set of V(G) independent paths that span the program's flow graph. These paths are selected such that any other path can be derived from their linear combinations, providing efficient yet comprehensive coverage of control structures like branches and loops. This method aligns closely with structural testing paradigms, emphasizing the exercise of code internals to confirm logical correctness.[8][4] In practice, higher V(G) values signal increased testing effort, as each additional independent path necessitates a distinct test case to cover potential execution scenarios. For instance, modules with V(G) exceeding 10 may require significantly more resources for path exploration compared to those with V(G) under 5, guiding testers in prioritizing complex components during verification planning. Tools like SonarQube automate V(G) computation and highlight high-complexity areas to inform effort allocation.[16] Automated tools further aid in generating test paths by analyzing the control flow graph and suggesting basis paths for test case design. Examples include PMD, which integrates cyclomatic complexity checks into build processes to flag and mitigate overly complex code before testing, and Visual Studio's code metrics features, which report V(G) to support path-based test generation. These tools streamline the process of deriving independent paths, reducing manual effort in creating executable test suites.[17] To illustrate, consider a control flow graph for a simple decision procedure with V(G) = 4, featuring nodes A (entry), B and E (decisions), C and D (branches from B), F (from E true), G (from E false or C/D), and H (exit). The four basis paths are:- Path 1: A → B (true) → C → G → H

- Path 2: A → B (false) → D → G → H

- Path 3: A → B (true) → C → E (true) → F → H

- Path 4: A → B (true) → C → E (false) → G → H