Recent from talks

Major Publications and Scientific Contributions

Main milestones

Family Life and Personal Relationships

Recognition and Legacy

Berlin Period (1741-1766)

Second St. Petersburg Period (1766-1783)

Early Life and Education (1707-1727)

First St. Petersburg Period (1727-1741)

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Leonhard Euler

View on Wikipedia

Leonhard Euler (/ˈɔɪlər/ OY-lər;[b] 15 April 1707 – 18 September 1783) was a Swiss polymath who was active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, logician, geographer, and engineer. He founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made influential discoveries in many other branches of mathematics, such as analytic number theory, complex analysis, and infinitesimal calculus. He also introduced much of modern mathematical terminology and notation, including the notion of a mathematical function.[3] He is known for his work in mechanics, fluid dynamics, optics, astronomy, and music theory.[4] Euler has been called a "universal genius" who "was fully equipped with almost unlimited powers of imagination, intellectual gifts and extraordinary memory".[5] He spent most of his adult life in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and in Berlin, then the capital of Prussia.

Key Information

Euler is credited for popularizing the Greek letter (lowercase pi) to denote the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, as well as first using the notation for the value of a function, the letter to express the imaginary unit , the Greek letter (capital sigma) to express summations, the Greek letter (capital delta) for finite differences, and lowercase letters to represent the sides of a triangle while representing the angles as capital letters.[6] He gave the current definition of the constant , the base of the natural logarithm, now known as Euler's number.[7] Euler made contributions to applied mathematics and engineering, such as his study of ships, which helped navigation; his three volumes on optics, which contributed to the design of microscopes and telescopes; and his studies of beam bending and column critical loads.[8]

Euler is credited with being the first to develop graph theory (partly as a solution for the problem of the Seven Bridges of Königsberg, which is also considered the first practical application of topology). He also became famous for, among many other accomplishments, solving several unsolved problems in number theory and analysis, including the famous Basel problem. Euler has also been credited for discovering that the sum of the numbers of vertices and faces minus the number of edges of a polyhedron that has no holes equals 2, a number now commonly known as the Euler characteristic. In physics, Euler reformulated Isaac Newton's laws of motion into new laws in his two-volume work Mechanica to better explain the motion of rigid bodies. He contributed to the study of elastic deformations of solid objects. Euler formulated the partial differential equations for the motion of inviscid fluid,[8] and laid the mathematical foundations of potential theory.[5]

Euler is regarded as arguably the most prolific contributor in the history of mathematics and science, and the greatest mathematician of the 18th century.[9][8] His 866 publications and his correspondence are being collected in the Opera Omnia Leonhard Euler.[10][11][12] Several great mathematicians who worked after Euler's death have recognised his importance in the field: Pierre-Simon Laplace said, "Read Euler, read Euler, he is the master of us all";[13][c] Carl Friedrich Gauss wrote: "The study of Euler's works will remain the best school for the different fields of mathematics, and nothing else can replace it."[14][d]

Early life

[edit]Leonhard Euler was born in Basel on 15 April 1707 to Paul III Euler, a pastor of the Reformed Church, and Marguerite (née Brucker), whose ancestors include a number of well-known scholars in the classics.[16] He was the oldest of four children, with two younger sisters, Anna Maria and Maria Magdalena, and a younger brother, Johann Heinrich.[17][16] Soon after Leonhard's birth, the Eulers moved from Basel to Riehen, Switzerland, where his father became pastor in the local church and Leonhard spent most of his childhood.[16]

From a young age, Euler received schooling in mathematics from his father, who had taken courses from Jacob Bernoulli some years earlier at the University of Basel. Around the age of eight, Euler was sent to live at his maternal grandmother's house and enrolled in the Latin school in Basel. In addition, he received private tutoring from Johannes Burckhardt, a young theologian with a keen interest in mathematics.[16]

In 1720, at age 13, Euler enrolled at the University of Basel.[4] Attending university at such a young age was not unusual at the time.[16] The course on elementary mathematics was given by Johann Bernoulli, the younger brother of the deceased Jacob Bernoulli, who had taught Euler's father. Johann Bernoulli and Euler soon got to know each other better. Euler described Bernoulli in his autobiography:[18]

the famous professor Johann Bernoulli [...] made it a special pleasure for himself to help me along in the mathematical sciences. Private lessons, however, he refused because of his busy schedule. However, he gave me a far more salutary advice, which consisted in myself getting a hold of some of the more difficult mathematical books and working through them with great diligence, and should I encounter some objections or difficulties, he offered me free access to him every Saturday afternoon, and he was gracious enough to comment on the collected difficulties, which was done with such a desired advantage that, when he resolved one of my objections, ten others at once disappeared, which certainly is the best method of making happy progress in the mathematical sciences.

During this time, Euler, backed by Bernoulli, obtained his father's consent to become a mathematician instead of a pastor.[19][20]

In 1723, Euler received a Master of Philosophy with a dissertation that compared the philosophies of René Descartes and Isaac Newton.[16] Afterwards, he enrolled in the theological faculty of the University of Basel.[20]

In 1726, Euler completed a dissertation on the propagation of sound titled De Sono,[21][22] with which he unsuccessfully attempted to obtain a position at the University of Basel.[23] In 1727, he entered the Paris Academy prize competition (offered annually and later biennially by the academy beginning in 1720)[24] for the first time. The problem posed that year was to find the best way to place the masts on a ship. Pierre Bouguer, who became known as "the father of naval architecture", won and Euler took second place.[25] Over the years, Euler entered this competition 15 times,[24] winning 12 of them.[25]

Career

[edit]First Saint Petersburg period (1727–1741)

[edit]

Johann Bernoulli's two sons, Daniel and Nicolaus, entered into service at the Imperial Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg in 1725, leaving Euler with the assurance they would recommend him to a post when one was available.[23] On 31 July 1726, Nicolaus died of appendicitis after spending less than a year in Russia.[26][27] When Daniel assumed his brother's position in the mathematics/physics division, he recommended that the post in physiology that he had vacated be filled by his friend Euler.[23] In November 1726, Euler eagerly accepted the offer, but delayed making the trip to Saint Petersburg while he unsuccessfully applied for a physics professorship at the University of Basel.[23]

Euler arrived in Saint Petersburg in May 1727.[23][20] He was promoted from his junior post in the medical department of the academy to a position in the mathematics department. He lodged with Daniel Bernoulli with whom he worked in close collaboration.[28] Euler mastered Russian, settled into life in Saint Petersburg and took on an additional job as a medic in the Russian Navy.[29]

The academy at Saint Petersburg, established by Peter the Great, was intended to improve education in Russia and to close the scientific gap with Western Europe. As a result, it was made especially attractive to foreign scholars like Euler.[25] The academy's benefactress, Catherine I, who had continued the progressive policies of her late husband, died before Euler's arrival to Saint Petersburg.[30] The Russian conservative nobility then gained power upon the ascension of the twelve-year-old Peter II.[30] The nobility, suspicious of the academy's foreign scientists, cut funding for Euler and his colleagues and prevented the entrance of foreign and non-aristocratic students into the Gymnasium and universities.[30]

Conditions improved slightly after the death of Peter II in 1730 and the German-influenced Anna of Russia assumed power.[31] Euler swiftly rose through the ranks in the academy and was made a professor of physics in 1731.[31] He also left the Russian Navy, refusing a promotion to lieutenant.[31] Two years later, Daniel Bernoulli, fed up with the censorship and hostility he faced at Saint Petersburg, left for Basel. Euler succeeded him as the head of the mathematics department.[32] In January 1734, he married Katharina Gsell (1707–1773), a daughter of Georg Gsell.[33] Frederick II had made an attempt to recruit the services of Euler for his newly established Berlin Academy in 1740, but Euler initially preferred to stay in St Petersburg.[34] But after Empress Anna died and Frederick II agreed to pay 1600 ecus (the same as Euler earned in Russia) he agreed to move to Berlin. In 1741, he requested permission to leave for Berlin, arguing he was in need of a milder climate for his eyesight.[34] The Russian academy gave its consent and would pay him 200 rubles per year as one of its active members.[34]

Berlin period (1741–1766)

[edit]Concerned about the continuing turmoil in Russia, Euler left St. Petersburg in June 1741 to take up a post at the Berlin Academy, which he had been offered by Frederick the Great of Prussia.[35] He lived for 25 years in Berlin, where he wrote several hundred articles.[20] In 1748 his text on functions called the Introductio in analysin infinitorum was published and in 1755 a text on differential calculus called the Institutiones calculi differentialis was published.[36][37] In 1755, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences[38] and of the French Academy of Sciences.[39] Notable students of Euler in Berlin included Stepan Rumovsky, later considered as the first Russian astronomer.[40][41] In 1748 he declined an offer from the University of Basel to succeed the recently deceased Johann Bernoulli.[20] In 1753 he bought a house in Charlottenburg, in which he lived with his family and widowed mother.[42][43]

Euler became the tutor for Friederike Charlotte of Brandenburg-Schwedt, the Princess of Anhalt-Dessau and Frederick's niece. He wrote over 200 letters to her in the early 1760s, which were later compiled into a volume entitled Letters of Euler on different Subjects in Natural Philosophy Addressed to a German Princess.[44] This work contained Euler's exposition on various subjects pertaining to physics and mathematics and offered valuable insights into Euler's personality and religious beliefs. It was translated into multiple languages, published across Europe and in the United States, and became more widely read than any of his mathematical works. The popularity of the Letters testifies to Euler's ability to communicate scientific matters effectively to a lay audience, a rare ability for a dedicated research scientist.[37]

Despite Euler's immense contribution to the academy's prestige and having been put forward as a candidate for its presidency by Jean le Rond d'Alembert, Frederick II named himself as its president.[43] The Prussian king had a large circle of intellectuals in his court, and he found the mathematician unsophisticated and ill-informed on matters beyond numbers and figures. Euler was a simple, devoutly religious man who never questioned the existing social order or conventional beliefs. He was, in many ways, the polar opposite of Voltaire, who enjoyed a high place of prestige at Frederick's court. Euler was not a skilled debater and often made it a point to argue subjects that he knew little about, making him the frequent target of Voltaire's wit.[37] Frederick also expressed disappointment with Euler's practical engineering abilities, stating:

I wanted to have a water jet in my garden: Euler calculated the force of the wheels necessary to raise the water to a reservoir, from where it should fall back through channels, finally spurting out in Sanssouci. My mill was carried out geometrically and could not raise a mouthful of water closer than fifty paces to the reservoir. Vanity of vanities! Vanity of geometry![45]

However, the disappointment was almost surely unwarranted from a technical perspective. Euler's calculations look likely to be correct, even if Euler's interactions with Frederick and those constructing his fountain may have been dysfunctional.[46]

Throughout his stay in Berlin, Euler maintained a strong connection to the academy in St. Petersburg and also published 109 papers in Russia.[47] He also assisted students from the St. Petersburg academy and at times accommodated Russian students in his house in Berlin.[47] In 1760, with the Seven Years' War raging, Euler's farm in Charlottenburg was sacked by advancing Russian troops.[42] Upon learning of this event, General Ivan Petrovich Saltykov paid compensation for the damage caused to Euler's estate, with Empress Elizabeth of Russia later adding a further payment of 4000 rubles—an exorbitant amount at the time.[48] Euler decided to leave Berlin in 1766 and return to Russia.[49]

During his Berlin years (1741–1766), Euler was at the peak of his productivity. He wrote 380 works, 275 of which were published.[50] This included 125 memoirs in the Berlin Academy and over 100 memoirs sent to the St. Petersburg Academy, which had retained him as a member and paid him an annual stipend. Euler's Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum was published in two parts in 1748. In addition to his own research, Euler supervised the library, the observatory, the botanical garden, and the publication of calendars and maps from which the academy derived income.[51] He was even involved in the design of the water fountains at Sanssouci, the King's summer palace.[52]

Second Saint Petersburg period (1766–1783)

[edit]The political situation in Russia stabilized after Catherine the Great's accession to the throne, so in 1766 Euler accepted an invitation to return to the St. Petersburg Academy. His conditions were quite exorbitant—a 3000 ruble annual salary, a pension for his wife, and the promise of high-ranking appointments for his sons. At the university he was assisted by his student Anders Johan Lexell.[53] While living in St. Petersburg, a fire in 1771 destroyed his home.[54]

Personal life

[edit]On 7 January 1734, Euler married Katharina Gsell, daughter of Georg Gsell, a painter at the Academy Gymnasium in Saint Petersburg.[33] The couple bought a house by the Neva River.

Of their 13 children, five survived childhood,[55] three sons and two daughters.[56] Their first son was Johann Albrecht Euler, whose godfather was Christian Goldbach.[56]

Three years after his wife's death in 1773,[54] Euler married her half-sister, Salome Abigail Gsell.[57] This marriage lasted until his death in 1783.

His brother Johann Heinrich settled in St. Petersburg in 1735 and was employed as a painter at the academy.[34]

Early in his life, Euler memorized Virgil's Aeneid, and by old age, he could recite the poem and give the first and last sentence on each page of the edition from which he had learnt it.[58][59] Euler knew the first hundred prime numbers and could give each of their powers up to the sixth degree.[60]

Euler was known as a generous and kind person, not neurotic as seen in some geniuses, keeping his good-natured disposition even after becoming entirely blind.[60]

Eyesight deterioration

[edit]Euler's eyesight worsened throughout his mathematical career. In 1738, three years after nearly dying of fever,[61] he became almost blind in his right eye. Euler blamed the cartography he performed for the St. Petersburg Academy for his condition,[62] but the cause of his blindness remains the subject of speculation.[63][64] Euler's vision in that eye worsened throughout his stay in Germany, to the extent that Frederick called him "Cyclops". Euler said of his loss of vision, "Now I will have fewer distractions."[62] In 1766 a cataract in his left eye was discovered. Though couching of the cataract temporarily improved his vision, complications rendered him almost totally blind in the left eye as well.[39] His condition appeared to have little effect on his productivity. With the aid of his scribes, Euler's productivity in many areas of study increased;[65] in 1775, he produced, on average, one mathematical paper per week.[39]

Death

[edit]

In St. Petersburg on 18 September 1783, after a lunch with his family, Euler was discussing the newly discovered planet Uranus and its orbit with Anders Johan Lexell when he collapsed and died of a brain hemorrhage.[63] Jacob von Staehlin wrote a short obituary for the Russian Academy of Sciences and Russian mathematician Nicolas Fuss, one of Euler's disciples, wrote a more detailed eulogy,[55] which he delivered at a memorial meeting. In his eulogy for the French Academy, French mathematician and philosopher Marquis de Condorcet wrote:

... il cessa de calculer et de vivre.

... he ceased to calculate and to live.[66]

Euler was buried next to Katharina at the Smolensk Lutheran Cemetery on Vasilievsky Island. In 1837, the Russian Academy of Sciences installed a new monument, replacing his overgrown grave plaque. In 1957, to commemorate the 250th anniversary of his birth, his tomb was moved to the Lazarevskoe Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery.[67]

Contributions to science

[edit]| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant e |

|---|

|

| Properties |

| Applications |

| Defining e |

| People |

| Related topics |

Euler worked in almost all areas of mathematics, including geometry, infinitesimal calculus, trigonometry, algebra, and number theory, as well as continuum physics, lunar theory, and other areas of physics. He is a seminal figure in the history of mathematics; if printed, his works, many of which are of fundamental interest, would occupy between 60 and 80 quarto volumes.[39] Euler's name is associated with a large number of topics. Euler's work averages 800 pages a year from 1725 to 1783. He also wrote over 4500 letters and hundreds of manuscripts. It has been estimated that Leonhard Euler was the author of a quarter of the combined output in mathematics, physics, mechanics, astronomy, and navigation in the 18th century, while other researchers credit Euler for a third of the output in mathematics in that century.[6]

Mathematical notation

[edit]Euler introduced and popularized several notational conventions through his numerous and widely circulated textbooks. Most notably, he introduced the concept of a function[3] and was the first to write f(x) to denote the function f applied to the argument x. He also introduced the modern notation for the trigonometric functions, the letter e for the base of the natural logarithm (now also known as Euler's number), the Greek letter Σ for summations and the letter i to denote the imaginary unit.[68] The use of the Greek letter π to denote the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter was also popularized by Euler, although it originated with Welsh mathematician William Jones.[69]

Analysis

[edit]The development of infinitesimal calculus was at the forefront of 18th-century mathematical research, and the Bernoullis—family friends of Euler—were responsible for much of the early progress in the field. Thanks to their influence, studying calculus became the major focus of Euler's work. While some of Euler's proofs are not acceptable by modern standards of mathematical rigour[70] (in particular his reliance on the principle of the generality of algebra), his ideas led to many great advances. Euler is well known in analysis for his frequent use and development of power series, the expression of functions as sums of infinitely many terms,[71] such as

Euler's use of power series enabled him to solve the Basel problem, finding the sum of the reciprocals of squares of every natural number, in 1735 (he provided a more elaborate argument in 1741). The Basel problem was originally posed by Pietro Mengoli in 1644, and by the 1730s was a famous open problem, popularized by Jacob Bernoulli and unsuccessfully attacked by many of the leading mathematicians of the time. Euler found that:[72][73][70]

Euler introduced the constant now known as Euler's constant or the Euler–Mascheroni constant, and studied its relationship with the harmonic series, the gamma function, and values of the Riemann zeta function.[74]

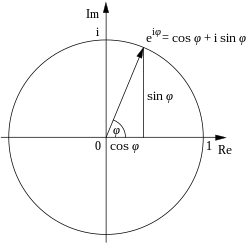

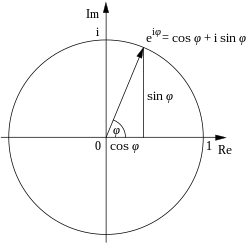

Euler introduced the use of the exponential function and logarithms in analytic proofs. He discovered ways to express various logarithmic functions using power series, and he successfully defined logarithms for negative and complex numbers, thus greatly expanding the scope of mathematical applications of logarithms.[68] He also defined the exponential function for complex numbers and discovered its relation to the trigonometric functions. For any real number φ (taken to be radians), Euler's formula states that the complex exponential function satisfies

which was called "the most remarkable formula in mathematics" by Richard Feynman.[75]

A special case of the above formula is known as Euler's identity,

Euler elaborated the theory of higher transcendental functions by introducing the gamma function[76][77] and introduced a new method for solving quartic equations.[78] He found a way to calculate integrals with complex limits, foreshadowing the development of modern complex analysis. He invented the calculus of variations and formulated the Euler–Lagrange equation for reducing optimization problems in this area to the solution of differential equations.

Euler pioneered the use of analytic methods to solve number theory problems. In doing so, he united two disparate branches of mathematics and introduced a new field of study, analytic number theory. In breaking ground for this new field, Euler created the theory of hypergeometric series, q-series, hyperbolic trigonometric functions, and the analytic theory of continued fractions. For example, he proved the infinitude of primes using the divergence of the harmonic series, and he used analytic methods to gain some understanding of the way prime numbers are distributed. Euler's work in this area led to the development of the prime number theorem.[79]

Number theory

[edit]Euler's interest in number theory can be traced to the influence of Christian Goldbach,[80] his friend in the St. Petersburg Academy.[61] Much of Euler's early work on number theory was based on the work of Pierre de Fermat. Euler developed some of Fermat's ideas and disproved some of his conjectures, such as his conjecture that all numbers of the form (Fermat numbers) are prime.[81]

Euler linked the nature of prime distribution with ideas in analysis. He proved that the sum of the reciprocals of the primes diverges. In doing so, he discovered the connection between the Riemann zeta function and prime numbers; this is known as the Euler product formula for the Riemann zeta function.[82]

Euler invented the totient function φ(n), the number of positive integers less than or equal to the integer n that are coprime to n. Using properties of this function, he generalized Fermat's little theorem to what is now known as Euler's theorem.[83] He contributed significantly to the theory of perfect numbers, which had fascinated mathematicians since Euclid. He proved that the relationship shown between even perfect numbers and Mersenne primes (which he had earlier proved) was one-to-one, a result otherwise known as the Euclid–Euler theorem.[84] Euler also conjectured the law of quadratic reciprocity. The concept is regarded as a fundamental theorem within number theory, and his ideas paved the way for the work of Carl Friedrich Gauss, particularly Disquisitiones Arithmeticae.[85] By 1772 Euler had proved that 231 − 1 = 2,147,483,647 is a Mersenne prime. It may have remained the largest known prime until 1867.[86]

Euler also contributed major developments to the theory of partitions of an integer.[87]

Graph theory

[edit]

In 1735, Euler presented a solution to the problem known as the Seven Bridges of Königsberg.[88] The city of Königsberg, Prussia was set on the Pregel River, and included two large islands that were connected to each other and the mainland by seven bridges. The problem is to decide whether it is possible to follow a path that crosses each bridge exactly once. Euler showed that it is not possible: there is no Eulerian path. This solution is considered to be the first theorem of graph theory.[88]

Euler also discovered the formula relating the number of vertices, edges, and faces of a convex polyhedron,[89] and hence of a planar graph. The constant in this formula is now known as the Euler characteristic for the graph (or other mathematical object), and is related to the genus of the object.[90] The study and generalization of this formula, specifically by Cauchy[91] and L'Huilier,[92] is at the origin of topology.[89]

Physics, astronomy, and engineering

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

Some of Euler's greatest successes were in solving real-world problems analytically, and in describing numerous applications of the Bernoulli numbers, Fourier series, Euler numbers, the constants e and π, continued fractions, and integrals. He integrated Leibniz's differential calculus with Newton's Method of Fluxions, and developed tools that made it easier to apply calculus to physical problems. He made great strides in improving the numerical approximation of integrals, inventing what are now known as the Euler approximations. The most notable of these approximations are Euler's method[93] and the Euler–Maclaurin formula.[94][95][96]

Euler helped develop the Euler–Bernoulli beam equation, which became a cornerstone of engineering.[97] Besides successfully applying his analytic tools to problems in classical mechanics, Euler applied these techniques to celestial problems. His work in astronomy was recognized by multiple Paris Academy Prizes over the course of his career. His accomplishments include determining with great accuracy the orbits of comets and other celestial bodies, understanding the nature of comets, and calculating the parallax of the Sun. His calculations contributed to the development of accurate longitude tables.[98]

Euler made important contributions in optics.[99] He disagreed with Newton's corpuscular theory of light,[100] which was the prevailing theory of the time. His 1740s papers on optics helped ensure that the wave theory of light proposed by Christiaan Huygens would become the dominant mode of thought, at least until the development of the quantum theory of light.[101]

In fluid dynamics, Euler was the first to predict the phenomenon of cavitation, in 1754, long before its first observation in the late 19th century, and the Euler number used in fluid flow calculations comes from his related work on the efficiency of turbines.[102] In 1757 he published an important set of equations for inviscid flow in fluid dynamics, that are now known as the Euler equations.[103]

Euler is well known in structural engineering for his formula giving Euler's critical load, the critical buckling load of an ideal strut, which depends only on its length and flexural stiffness.[104]

Logic

[edit]Euler is credited with using closed curves to illustrate syllogistic reasoning (1768). These diagrams have become known as Euler diagrams.[105]

An Euler diagram is a diagrammatic means of representing sets and their relationships. Euler diagrams consist of simple closed curves (usually circles) in the plane that depict sets. Each Euler curve divides the plane into two regions or "zones": the interior, which symbolically represents the elements of the set, and the exterior, which represents all elements that are not members of the set. The sizes or shapes of the curves are not important; the significance of the diagram is in how they overlap. The spatial relationships between the regions bounded by each curve (overlap, containment or neither) corresponds to set-theoretic relationships (intersection, subset, and disjointness). Curves whose interior zones do not intersect represent disjoint sets. Two curves whose interior zones intersect represent sets that have common elements; the zone inside both curves represents the set of elements common to both sets (the intersection of the sets). A curve that is contained completely within the interior zone of another represents a subset of it.

Euler diagrams (and their refinement to Venn diagrams) were incorporated as part of instruction in set theory as part of the new math movement in the 1960s.[106] Since then, they have come into wide use as a way of visualizing combinations of characteristics.[107]

Demography

[edit]In his 1760 paper A General Investigation into the Mortality and Multiplication of the Human Species Euler produced a model which showed how a population with constant fertility and mortality might grow geometrically using a difference equation. Under this geometric growth Euler also examined relationships among various demographic indices showing how they might be used to produce estimates when observations were missing. Three papers published around 150 years later by Alfred J. Lotka (1907, 1911 (with F.R. Sharpe) and 1922) adopted a similar approach to Euler's and produced their Stable Population Model. These marked the start of 20th century formal demographic modelling.[108][109][110][111][112][113]

Music

[edit]One of Euler's more unusual interests was the application of mathematical ideas in music. In 1739 he wrote the Tentamen novae theoriae musicae (Attempt at a New Theory of Music), hoping to eventually incorporate musical theory as part of mathematics. This part of his work, however, did not receive wide attention and was once described as too mathematical for musicians and too musical for mathematicians.[114] Even when dealing with music, Euler's approach is mainly mathematical,[115] for instance, his introduction of binary logarithms as a way of numerically describing the subdivision of octaves into fractional parts.[116] His writings on music are not particularly numerous (a few hundred pages, in his total production of about thirty thousand pages), but they reflect an early preoccupation and one that remained with him throughout his life.[115]

A first point of Euler's musical theory is the definition of "genres", i.e. of possible divisions of the octave using the prime numbers 3 and 5. Euler describes 18 such genres, with the general definition 2mA, where A is the "exponent" of the genre (i.e. the sum of the exponents of 3 and 5) and 2m (where "m is an indefinite number, small or large, so long as the sounds are perceptible"[117]), expresses that the relation holds independently of the number of octaves concerned. The first genre, with A = 1, is the octave itself (or its duplicates); the second genre, 2m.3, is the octave divided by the fifth (fifth + fourth, C–G–C); the third genre is 2m.5, major third + minor sixth (C–E–C); the fourth is 2m.32, two-fourths and a tone (C–F–B♭–C); the fifth is 2m.3.5 (C–E–G–B–C); etc. Genres 12 (2m.33.5), 13 (2m.32.52) and 14 (2m.3.53) are corrected versions of the diatonic, chromatic and enharmonic, respectively, of the Ancients. Genre 18 (2m.33.52) is the "diatonico-chromatic", "used generally in all compositions",[118] and which turns out to be identical with the system described by Johann Mattheson.[119] Euler later envisaged the possibility of describing genres including the prime number 7.[120]

Euler devised a specific graph, the Speculum musicum,[121][122] to illustrate the diatonico-chromatic genre, and discussed paths in this graph for specific intervals, recalling his interest in the Seven Bridges of Königsberg (see above). The device drew renewed interest as the Tonnetz in Neo-Riemannian theory (see also Lattice (music)).[123]

Euler further used the principle of the "exponent" to propose a derivation of the gradus suavitatis (degree of suavity, of agreeableness) of intervals and chords from their prime factors – one must keep in mind that he considered just intonation, i.e. 1 and only the prime numbers 3 and 5.[124] Formulas have been proposed extending this system to any number of prime numbers, e.g. in the form where pi are prime numbers and ki their exponents.[125]

Personal philosophy and religious beliefs

[edit]Euler was religious throughout his life.[20] Much of what is known of his religious beliefs can be deduced from his Letters to a German Princess and an earlier work, Rettung der Göttlichen Offenbahrung gegen die Einwürfe der Freygeister (Defense of the Divine Revelation against the Objections of the Freethinkers). These show that Euler was a devout Christian who believed the Bible to be inspired; the Rettung was primarily an argument for the divine inspiration of scripture.[126][127]

Euler opposed the concepts of Leibniz's monadism and the philosophy of Christian Wolff.[128] He insisted that knowledge is founded in part on the basis of precise quantitative laws, something that monadism and Wolffian science were unable to provide. Euler called Wolff's ideas "heathen and atheistic".[129]

There is a legend[130] inspired by Euler's arguments with secular philosophers over religion, which is set during Euler's second stint at the St. Petersburg Academy. The French philosopher Denis Diderot was visiting Russia on Catherine the Great's invitation. The Empress was alarmed that Diderot's arguments for atheism were influencing members of her court, and so Euler was asked to confront him. Diderot was informed that a learned mathematician had produced a proof of the existence of God: he agreed to view the proof as it was presented in court. Euler appeared, advanced toward Diderot, and in a tone of perfect conviction announced this non sequitur:

"Sir, , hence God exists –reply!"

Diderot, to whom (says the story) all mathematics was gibberish, stood dumbstruck as peals of laughter erupted from the court. Embarrassed, he asked to leave Russia, a request Catherine granted. However amusing the anecdote may be, it is apocryphal, given that Diderot himself did research in mathematics.[131] The legend was apparently first told by Dieudonné Thiébault with embellishment by Augustus De Morgan.[130]

Legacy

[edit]Recognition

[edit]Euler is widely recognized as one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, and more likely than not the most prolific contributor to mathematics and science.[8] Mathematician and physicist John von Neumann called Euler "the greatest virtuoso of the period".[132] Mathematician François Arago said, "Euler calculated without any apparent effort, just as men breathe and as eagles sustain themselves in air".[133] He is generally ranked right below Carl Friedrich Gauss, Isaac Newton, and Archimedes among the greatest mathematicians of all time,[133] while some rank him as equal with them.[134] Physicist and mathematician Henri Poincaré called Euler the "god of mathematics".[135]

French mathematician André Weil noted that Euler stood above his contemporaries and more than anyone else was able to cement himself as the leading force of his era's mathematics:[132]

No mathematician ever attained such a position of undisputed leadership in all branches of mathematics, pure and applied, as Euler did for the best part of the eighteenth century.

Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fuss noted Euler's extraordinary memory and breadth of knowledge, saying:[5]

Knowledge that we call erudition was not inimical to him. He had read all the best Roman writers, knew perfectly the ancient history of mathematics, held in his memory the historical events of all times and peoples, and could without hesitation adduce by way of examples the most trifling of historical events. He knew more about medicine, botany, and chemistry than might be expected of someone who had not worked especially in those sciences.

Commemorations

[edit]

Euler was featured on both the sixth[136] and seventh[137] series of the Swiss 10-franc banknote and on numerous Swiss, German, and Russian postage stamps. In 1782 he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[138] The asteroid 2002 Euler was named in his honour.[139]

Selected bibliography

[edit]Euler has an extensive bibliography. His books include:

- Mechanica (1736)

- Methodus inveniendi lineas curvas maximi minimive proprietate gaudentes, sive solutio problematis isoperimetrici latissimo sensu accepti (1744)[140] (A method for finding curved lines enjoying properties of maximum or minimum, or solution of isoperimetric problems in the broadest accepted sense)[141]

- Introductio in analysin infinitorum (1748)[142][143] (Introduction to Analysis of the Infinite)[144]

- Institutiones calculi differentialis (1755)[143][145] (Foundations of differential calculus)

- Vollständige Anleitung zur Algebra (1765)[143] (Elements of Algebra)

- Institutiones calculi integralis (1768–1770)[143] (Foundations of integral calculus)

- Letters to a German Princess (1768–1772)[37]

- Dioptrica, published in three volumes beginning in 1769[99]

It took until 1830 for the bulk of Euler's posthumous works to be individually published,[146] with an additional batch of 61 unpublished works discovered by Paul Heinrich von Fuss (Euler's great-grandson and Nicolas Fuss's son) and published as a collection in 1862.[146][147] A chronological catalog of Euler's works was compiled by Swedish mathematician Gustaf Eneström and published from 1910 to 1913.[148] The catalog, known as the Eneström index, numbers Euler's works from E1 to E866.[149] The Euler Archive was started at Dartmouth College[150] before moving to the Mathematical Association of America[151] and, most recently, to University of the Pacific in 2017.[152]

In 1907, the Swiss Academy of Sciences created the Euler Commission and charged it with the publication of Euler's complete works. After several delays in the 19th century,[146] the first volume of the Opera Omnia, was published in 1911.[153] However, the discovery of new manuscripts continued to increase the magnitude of this project. Fortunately, the publication of Euler's Opera Omnia has made steady progress, with over 70 volumes (averaging 426 pages each) published by 2006 and 80 volumes published by 2022.[154][11][6] These volumes are organized into four series. The first series compiles the works on analysis, algebra, and number theory; it consists of 29 volumes and numbers over 14,000 pages. The 31 volumes of Series II, amounting to 10,660 pages, contain the works on mechanics, astronomy, and engineering. Series III contains 12 volumes on physics. Series IV, which contains the massive amount of Euler's correspondence, unpublished manuscripts, and notes only began compilation in 1967. After publishing 8 print volumes in Series IV, the project decided in 2022 to publish its remaining projected volumes in Series IV in online format only.[11][153][6]

-

Illustration from Solutio problematis... a. 1743 propositi published in Acta Eruditorum, 1744

-

The title page of Euler's Methodus inveniendi lineas curvas

-

Euler's 1760 world map

-

Euler's 1753 map of Africa

Notes

[edit]- ^ Euler is listed by an academic genealogy as the equivalent to the doctoral advisor of Lagrange.[1]

- ^ In English Euler's name is pronounced /ˈɔɪlər/ ⓘ OY-lər; the pronunciation /ˈjuːlər/ YOO-lər is considered incorrect.[2] Swiss Standard German: [ˈleːɔnhard ˈɔʏlər]. German: [ˈleːɔnhaʁt ˈɔʏlɐ] ⓘ.

- ^ The quote appeared in Gugliemo Libri's review of a recently published collection of correspondence among eighteenth-century mathematicians: "... nous rappellerions que Laplace lui même, ... ne cessait de répéter aux jeunes mathématiciens ces paroles mémorables que nous avons entendues de sa propre bouche : 'Lisez Euler, lisez Euler, c'est notre maître à tous.'" [... we would recall that Laplace himself, ... never ceased to repeat to young mathematicians these memorable words that we heard from his own mouth: 'Read Euler, read Euler, he is our master in everything.'][155]

- ^ Gauss wrote this in a letter to Paul Fuss dated September 11, 1849:[15] "Die besondere Herausgabe der kleinern Eulerschen Abhandlungen ist gewiß etwas höchst verdienstliches, [...] und das Studium aller Eulerschen Arbeiten doch stets die beste durch nichts anderes zu ersetzende Schule für die verschiedenen mathematischen Gebiete bleiben wird." [The special publication of the smaller Euler treatises is certainly something highly deserving, [...] and the study of all Euler's works will always remain the best school for the various mathematical fields, which cannot be replaced by anything else.]

References

[edit]- ^ Leonhard Euler at the Mathematics Genealogy Project Retrieved 2021-07-02

- ^

"Euler". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

"Euler". Merriam–Webster's Online Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

"Euler, Leonhard". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 2011. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

Higgins, Peter M. (2007). Nets, Puzzles, and Postmen: An Exploration of Mathematical Connections. Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-19-921842-4.

- ^ a b Dunham 1999, p. 17.

- ^ a b Debnath, Lokenath (2010). The Legacy of Leonhard Euler: A Tricentennial Tribute. London: Imperial College Press. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-84816-525-0.

- ^ a b c Debnath, Lokenath (2010). The Legacy of Leonhard Euler: A Tricentennial Tribute. London: Imperial College Press. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-84816-525-0.

- ^ a b c d Assad, Arjang A. (2007). "Leonhard Euler: A brief appreciation". Networks. 49 (3): 190–198. doi:10.1002/net.20158. S2CID 11298706.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B (1 June 2021). "Leonhard Euler". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ a b c d Debnath, Lokenath (15 April 2009). "The legacy of Leonhard Euler – a tricentennial tribute". International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 40 (3): 353–388. doi:10.1080/00207390802642237. ISSN 0020-739X.

- ^ Goldman, Jay R. (1998). The Queen of Mathematics: A Historically Motivated Guide to Number Theory. A.K. Peters. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-56881-006-5.

- ^ "Leonhardi Euleri Opera Omnia (LEOO)". Bernoulli Euler Center. Archived from the original on 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ a b c "The works". Bernoulli-Euler Society. Archived from the original on 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ Gautschi 2008, p. 3.

- ^ Dunham 1999, p. xiii "Lisez Euler, lisez Euler, c'est notre maître à tous."

- ^ Grinstein, Louise; Lipsey, Sally I. (2001). "Euler, Leonhard (1707–1783)". Encyclopedia of Mathematics Education. Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-415-76368-4.

- ^ Fuß, Paul Heinrich; Gauß, Carl Friedrich (11 September 1849). "Carl Friedrich Gauß → Paul Heinrich Fuß, Göttingen, 1849 Sept. 11".

- ^ a b c d e f Gautschi 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Calinger 2016, p. 11.

- ^ Gautschi 2008, p. 5.

- ^ Calinger 1996, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f Knobloch, Eberhard; Louhivaara, I. S.; Winkler, J., eds. (May 1983). Zum Werk Leonhard Eulers: Vorträge des Euler-Kolloquiums im Mai 1983 in Berlin (PDF). Birkhäuser Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-7121-1. ISBN 978-3-0348-7122-8.

- ^ Calinger 2016, p. 32.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1727). Dissertatio physica de sono [Physical dissertation on sound] (in Latin). Basel: E. and J. R. Thurnisiorum. Retrieved 2021-06-06 – via Euler archive.

Translated into English as

Bruce, Ian. "Euler's Dissertation De Sono: E002" (PDF). Some Mathematical Works of the 17th & 18th Centuries, including Newton's Principia, Euler's Mechanica, Introductio in Analysin, etc., translated mainly from Latin into English. Retrieved 2021-06-12. - ^ a b c d e Calinger 1996, p. 125.

- ^ a b "The Paris Academy". Euler Archive. Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ a b c Calinger 1996, p. 156.

- ^ Calinger 1996, pp. 121–166.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. "Nicolaus (II) Bernoulli". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2021-07-02.

- ^ Calinger 1996, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Calinger 1996, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Calinger 1996, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Calinger 1996, p. 128.

- ^ Calinger 1996, pp. 128–129.

- ^ a b Gekker & Euler 2007, p. 402.

- ^ a b c d Calinger 1996, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Gautschi 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1787). "Institutiones calculi differentialis cum eius usu in analysi finitorum ac doctrina serierum" [Foundations of Differential Calculus, with Applications to Finite Analysis and Series]. Academiae Imperialis Scientiarum Petropolitanae (in Latin). 1. Petri Galeatii: 1–880. Retrieved 2021-06-08 – via Euler Archive.

- ^ a b c d Dunham 1999, pp. xxiv–xxv.

- ^ Stén, Johan C.-E. (2014). "Academic events in Saint Petersburg". A Comet of the Enlightenment. Vita Mathematica. Vol. 17. Birkhäuser. pp. 119–135. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-00618-5_7. ISBN 978-3-319-00617-8. See in particular footnote 37, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d Finkel, B. F. (1897). "Biography – Leonhard Euler". The American Mathematical Monthly. 4 (12): 297–302. doi:10.2307/2968971. JSTOR 2968971. MR 1514436.

- ^ Balashov, Yuri (2007). "Rumovsky, Stepan Yakovlevich". In Hockey, Thomas; et al. (eds.). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 991–992. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-30400-7_1196. ISBN 978-0-387-30400-7.

- ^ Clark, William; Golinski, Jan; Schaffer, Simon (1999). The Sciences in Enlightened Europe. University of Chicago Press. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-226-10940-4. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ a b Knobloch, Eberhard (2007). "Leonhard Euler 1707–1783. Zum 300. Geburtstag eines langjährigen Wahlberliners". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung. 15 (4): 276–288. doi:10.1515/dmvm-2007-0092. S2CID 122271644.

- ^ a b Gautschi 2008, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1802). Letters of Euler on Different Subjects of Physics and Philosophy, Addressed to a German Princess. Translated by Hunter, Henry (2nd ed.). London: Murray and Highley. Archived via Internet Archives

- ^ Frederick II of Prussia (1927). Letters of Voltaire and Frederick the Great, Letter H 7434, 25 January 1778. Richard Aldington. New York: Brentano's.

- ^ Lynch, Peter (September 2017). "Euler and the failed fountain of Sanssouci — that's maths: Frederick the Great ignored the advice of a genius in maths and physics". Irish Times. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ a b Vucinich, Alexander (1960). "Mathematics in Russian Culture". Journal of the History of Ideas. 21 (2): 164–165. doi:10.2307/2708192. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708192.

- ^ Gindikin, Simon (2007). "Leonhard Euler". Tales of Mathematicians and Physicists. Springer Publishing. pp. 171–212. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-48811-0_7. ISBN 978-0-387-48811-0. See in particular p. 182.

- ^ Gautschi 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Knobloch, Eberhard (1998). "Mathematics at the Prussian Academy of Sciences 1700–1810". In Begehr, Heinrich; Koch, Helmut; Kramer, Jürg; Schappacher, Norbert; Thiele, Ernst-Jochen (eds.). Mathematics in Berlin. Basel: Birkhäuser Basel. pp. 1–8. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-8787-8_1. ISBN 978-3-7643-5943-0.

- ^ Thiele, Rüdiger (2005). "The Mathematics and Science of Leonhard Euler (1707–1783)". Mathematics and the Historian's Craft. CMS Books in Mathematics. New York: Springer Publishing. pp. 81–140. doi:10.1007/0-387-28272-6_6. ISBN 978-0-387-25284-1.

- ^ Eckert, Michael (2002). "Euler and the Fountains of Sanssouci". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 56 (6): 451–468. doi:10.1007/s004070200054. ISSN 0003-9519. S2CID 121790508.

- ^ Maehara, Hiroshi; Martini, Horst (2017). "On Lexell's Theorem". The American Mathematical Monthly. 124 (4): 337–344. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.124.4.337. ISSN 0002-9890. JSTOR 10.4169/amer.math.monthly.124.4.337. S2CID 125175471.

- ^ a b Thiele, Rüdiger (2005). "The mathematics and science of Leonhard Euler". In Kinyon, Michael; van Brummelen, Glen (eds.). Mathematics and the Historian's Craft: The Kenneth O. May Lectures. Springer Publishing. pp. 81–140. ISBN 978-0-387-25284-1.

- ^ a b Fuss, Nicolas (1783). "Éloge de M. Léonhard Euler" [Eulogy for Leonhard Euler]. Nova Acta Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae (in French). 1: 159–212. Retrieved 2018-05-19 – via Bioheritage Diversity Library. Translated into English as "Eulogy of Leonhard Euler by Nicolas Fuss". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Translated by Glaus, John S. D. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ^ a b Calinger 1996, p. 129.

- ^ Gekker & Euler 2007, p. 405.

- ^ Meade, Phil (27 November 1999). "Letter: Uncommon talent". www.newscientist.com. Retrieved 2024-09-22.

- ^ Nahin, Paul J. (2017). Dr. Euler's Fabulous Formula: Cures Many Mathematical Ills. Princeton Science Library. Princeton Oxford: Princeton University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-691-17591-1.

- ^ a b Lynch, Peter (21 January 2021). "Euler: a mathematician without equal and an overall nice guy". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ a b Gautschi 2008, p. 6.

- ^ a b Eves, Howard W. (1969). "Euler's blindness". In Mathematical Circles: A Selection of Mathematical Stories and Anecdotes, Quadrants III and IV. Prindle, Weber, & Schmidt. p. 48. OCLC 260534353. Also quoted by Richeson (2012), p. 17, cited to Eves.

- ^ a b Asensi, Victor; Asensi, Jose M. (March 2013). "Euler's right eye: the dark side of a bright scientist". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 57 (1): 158–159. doi:10.1093/cid/cit170. PMID 23487386.

- ^ Bullock, John D.; Warwar, Ronald E.; Hawley, H. Bradford (April 2022). "Why was Leonhard Euler blind?". British Journal for the History of Mathematics. 37: 24–42. doi:10.1080/26375451.2022.2052493. S2CID 247868159.

- ^ Gautschi 2008, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Marquis de Condorcet. "Eulogy of Euler – Condorcet". Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ^ Calinger 2016, pp. 530–536.

- ^ a b Boyer, Carl B.; Merzbach, Uta C. (1991). A History of Mathematics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 439–445. ISBN 978-0-471-54397-8.

- ^ Arndt, Jörg; Haenel, Christoph (2006). Pi Unleashed. Springer-Verlag. p. 166. ISBN 978-3-540-66572-4. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- ^ a b Wanner, Gerhard; Hairer, Ernst (2005). Analysis by its history (1st ed.). Springer Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-387-77036-9.

- ^ Ferraro 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Morris, Imogen I. (24 October 2023). Mechanising Euler's use of Infinitesimals in the Proof of the Basel Problem (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. doi:10.7488/ERA/3835.

- ^ Dunham 1999.

- ^ Lagarias, Jeffrey C. (October 2013). "Euler's constant: Euler's work and modern developments". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 50 (4): 556. arXiv:1303.1856. doi:10.1090/s0273-0979-2013-01423-x. MR 3090422. S2CID 119612431.

- ^ Feynman, Richard (1970). "Chapter 22: Algebra". The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Vol. I. p. 10.

- ^ Ferraro 2008, p. 159.

- ^ Davis, Philip J. (1959). "Leonhard Euler's integral: A historical profile of the gamma function". The American Mathematical Monthly. 66: 849–869. doi:10.2307/2309786. JSTOR 2309786. MR 0106810.

- ^ Nickalls, R. W. D. (March 2009). "The quartic equation: invariants and Euler's solution revealed". The Mathematical Gazette. 93 (526): 66–75. doi:10.1017/S0025557200184190. JSTOR 40378672. S2CID 16741834.

- ^ Dunham 1999, Ch. 3, Ch. 4.

- ^ Calinger 1996, p. 130.

- ^ Dunham 1999, p. 7.

- ^ Patterson, S. J. (1988). An introduction to the theory of the Riemann zeta-function. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. Vol. 14. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511623707. ISBN 978-0-521-33535-5. MR 0933558. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- ^ Shiu, Peter (November 2007). "Euler's contribution to number theory". The Mathematical Gazette. 91 (522): 453–461. doi:10.1017/S0025557200182099. JSTOR 40378418. S2CID 125064003.

- ^ Stillwell, John (2010). Mathematics and Its History. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4419-6052-8. Retrieved 2021-06-06..

- ^ Dunham 1999, Ch. 1, Ch. 4.

- ^ Caldwell, Chris. "The largest known prime by year". PrimePages. University of Tennessee at Martin. Retrieved 2021-06-09.

- ^ Hopkins, Brian; Wilson, Robin (2007). "Euler's science of combinations". Leonhard Euler: Life, Work and Legacy. Stud. Hist. Philos. Math. Vol. 5. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 395–408. MR 3890500.

- ^ a b Alexanderson, Gerald (July 2006). "Euler and Königsberg's bridges: a historical view". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 43 (4): 567. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-06-01130-X.

- ^ a b Richeson 2012.

- ^ Gibbons, Alan (1985). Algorithmic Graph Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-28881-1. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- ^ Cauchy, A. L. (1813). "Recherche sur les polyèdres – premier mémoire". Journal de l'École polytechnique (in French). 9 (Cahier 16): 66–86. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ L'Huillier, S.-A.-J. (1812–1813). "Mémoire sur la polyèdrométrie". Annales de mathématiques pures et appliquées. 3: 169–189. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ Butcher, John C. (2003). Numerical Methods for Ordinary Differential Equations. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-471-96758-3. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- ^ Calinger 2016, pp. 96, 137.

- ^ Ferraro 2008, pp. 171–180, Chapter 14: Euler's derivation of the Euler–Maclaurin summation formula.

- ^ Mills, Stella (1985). "The independent derivations by Leonhard Euler and Colin Maclaurin of the Euler–Maclaurin summation formula". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 33 (1–3): 1–13. doi:10.1007/BF00328047. MR 0795457. S2CID 122119093.

- ^ Ojalvo, Morris (December 2007). "Three hundred years of bar theory". Journal of Structural Engineering. 133 (12): 1686–1689. doi:10.1061/(asce)0733-9445(2007)133:12(1686).

- ^ Youschkevitch, A. P. (1971). "Euler, Leonhard". In Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 4: Richard Dedekind – Firmicus Maternus. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 467–484. ISBN 978-0-684-16964-4.

- ^ a b Davidson, Michael W. (February 2011). "Pioneers in Optics: Leonhard Euler and Étienne-Louis Malus". Microscopy Today. 19 (2): 52–54. doi:10.1017/s1551929511000046. S2CID 122853454.

- ^ Calinger 1996, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Home, R. W. (1988). "Leonhard Euler's 'anti-Newtonian' theory of light". Annals of Science. 45 (5): 521–533. doi:10.1080/00033798800200371. MR 0962700.

- ^ Li, Shengcai (October 2015). "Tiny bubbles challenge giant turbines: Three Gorges puzzle". Interface Focus. 5 (5) 20150020. Royal Society. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2015.0020. PMC 4549846. PMID 26442144.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1757). "Principes généraux de l'état d'équilibre d'un fluide" [General principles of the state of equilibrium of a fluid]. Académie Royale des Sciences et des Belles-Lettres de Berlin, Mémoires (in French). 11: 217–273. Retrieved 2021-06-12. Translated into English as Frisch, Uriel (2008). "Translation of Leonhard Euler's: General Principles of the Motion of Fluids". arXiv:0802.2383 [nlin.CD].

- ^ Gautschi 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Baron, Margaret E. (May 1969). "A note on the historical development of logic diagrams". The Mathematical Gazette. 53 (383): 113–125. doi:10.2307/3614533. JSTOR 3614533. S2CID 125364002.

- ^ Lemanski, Jens (2016). "Means or end? On the valuation of logic diagrams". Logic-Philosophical Studies. 14: 98–122.

- ^ Rodgers, Peter (June 2014). "A survey of Euler diagrams" (PDF). Journal of Visual Languages & Computing. 25 (3): 134–155. doi:10.1016/j.jvlc.2013.08.006. S2CID 2571971. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ Smith, D.P. and N. Keyfitz, (2013) Mathematical Demography: Selected Papers, Monographs, DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-35858-6_1 Springer-Verlag Demographic Research - Euler, L. (1760). 11. A general investigation into the mortality and multiplication of the human species. A General Investigation into the Mortality and Multiplication of the Human Species, Theoretical Population Biology 1: 307-314. Translated by Nathan and Beatrice Keyfitz

- ^ Newell, Colin. (1988) Methods and models in demography. Belhaven Press.

- ^ Inaba, Hisashi (2017) Chapter 1 The Stable Population Model in Age-structured population dynamics in demography and epidemiology. Springer Singapore.

- ^ Lotka, A. J. (1907). Relation between birth rates and death rates. Science, 26(653), 21-22.

- ^ Sharpe, F. R., & Lotka, A. J. (1911). L. A problem in age-distribution. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 21(124), 435-438.

- ^ Lotka, A. J. (1922). The stability of the normal age distribution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 8(11), 339-345.

- ^ Calinger 1996, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b Pesic, Peter (2014). "Euler: the mathematics of musical sadness; Euler: from sound to light". Music and the Making of Modern Science. MIT Press. pp. 133–160. ISBN 978-0-262-02727-4. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ Tegg, Thomas (1829). "Binary logarithms". London encyclopaedia; or, Universal dictionary of science, art, literature and practical mechanics: comprising a popular view of the present state of knowledge, Volume 4. pp. 142–143. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Euler 1739, p. 115.

- ^ Emery, Eric (2000). Temps et musique. Lausanne: L'Âge d'homme. pp. 344–345.

- ^ Mattheson, Johannes (1731). Grosse General-Baß-Schule. Vol. I. Hamburg. pp. 104–106. OCLC 30006387. Mentioned by Euler. Also: Mattheson, Johannes (1719). Exemplarische Organisten-Probe. Hamburg. pp. 57–59.

- ^ See:

- Perret, Wilfrid (1926). Some Questions of Musical Theory. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. pp. 60–62. OCLC 3212114.

- "What is an Euler-Fokker genus?". Microtonality. Huygens-Fokker Foundation. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ Euler 1739, p. 147.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1774). "De harmoniae veris principiis per speculum musicum repraesentatis". Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae. 18. Eneström index 457: 330–353. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ Gollin, Edward (2009). "Combinatorial and transformational aspects of Euler's Speculum Musicum". In Klouche, T.; Noll, Th. (eds.). Mathematics and Computation in Music: First International Conference, MCM 2007 Berlin, Germany, May 18–20, 2007, Revised Selected Papers. Communications in Computer and Information Science. Vol. 37. Springer. pp. 406–411. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04579-0_40. ISBN 978-3-642-04578-3.

- ^ Lindley, Mark; Turner-Smith, Ronald (1993). Mathematical Models of Musical Scales: A New Approach. Bonn: Verlag für Systematische Musikwissenschaft. pp. 234–239. ISBN 978-3-922626-66-4. OCLC 27789639. See also Nolan, Catherine (2002). "Music Theory and Mathematics". In Christensen, Th. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 278–279. ISBN 978-1-139-05347-1. OCLC 828741887.

- ^ Bailhache, Patrice (17 January 1997). "La Musique traduite en Mathématiques: Leonhard Euler". Communication au colloque du Centre François Viète, "Problèmes de traduction au XVIIIe siècle", Nantes (in French). Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1747). Rettung der Göttlichen Offenbahrung gegen die Einwürfe der Freygeister [Defense of divine revelation against the objections of the freethinkers] (in German). Eneström index 92. Berlin: Ambrosius Haude and Johann Carl Spener. Retrieved 2021-06-12 – via Euler Archive.

- ^ Marquis de Condorcet (1805). Comparison to the Last Edition of Euler's Letters Published by de Condorcet, with the Original Edition: A Defense of the Revelation Against the Objections of Freethinkers, by Mr. Euler Followed by Thoughts by the Author on Religion, Omitted From the Last Edition of his Letters to a Princess of Germany (PDF). Translated by Ho, Andie. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ Calinger 1996, p. 123.

- ^ Calinger 1996, pp. 153–154

- ^ a b See:

- Brown, B. H. (May 1942). "The Euler–Diderot anecdote". The American Mathematical Monthly. 49 (5): 302–303. doi:10.2307/2303096. JSTOR 2303096.

- Gillings, R. J. (February 1954). "The so-called Euler–Diderot incident". The American Mathematical Monthly. 61 (2): 77–80. doi:10.2307/2307789. JSTOR 2307789.

- Struik, Dirk J. (1967). A Concise History of Mathematics (3rd revised ed.). Dover Books. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-486-60255-4.

- ^ Marty, Jacques (1988). "Quelques aspects des travaux de Diderot en " mathématiques mixtes "" [Some aspects of Diderot's work in general mathematics]. Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie (in French). 4 (1): 145–147. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- ^ a b Debnath, Lokenath (2010). The Legacy of Leonhard Euler: A Tricentennial Tribute. London: Imperial College Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84816-525-0.

- ^ a b Davis, Donald M. (2004). The Nature and Power of Mathematics. Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-486-43896-2. OCLC 56214613.

- ^ Calinger 2016, p. ix.

- ^ Calinger 2016, p. 241.

- ^ "Schweizerische Nationalbank (SNB) – Sechste Banknotenserie (1976)". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ "Schweizerische Nationalbank (SNB) – Siebte Banknotenserie (1984)". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ "E" (PDF). Members of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 1780–2017. American Academy of Arts and Sciences. pp. 164–179. Retrieved 2019-02-17. Entry for Euler is on p. 177.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D., ed. (2007). "(2002) Euler". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Publishing. p. 162. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_2003. ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7.

- ^ Fraser, Craig G. (11 February 2005). Leonhard Euler's 1744 book on the calculus of variations. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4. In Grattan-Guinness 2005, pp. 168–180

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1744). Methodus inveniendi lineas curvas maximi minimive proprietate gaudentes, sive solutio problematis isoperimetrici lattissimo sensu accepti [A method for finding curved lines enjoying properties of maximum or minimum, or solution of isoperimetric problems in the broadest accepted sense] (in Latin). Bosquet. Retrieved 2021-06-08 – via Euler archive.

- ^ Reich, Karin (11 February 2005). 'Introduction' to analysis. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4. In Grattan-Guinness 2005, pp. 181–190

- ^ a b c d Ferraro, Giovanni (2007). "Euler's treatises on infinitesimal analysis: Introductio in analysin infinitorum, institutiones calculi differentialis, institutionum calculi integralis". In Baker, Roger (ed.). Euler Reconsidered: Tercentenary Essays (PDF). Heber City, UT: Kendrick Press. pp. 39–101. MR 2384378. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-09-12.

- ^ Reviews of Introduction to Analysis of the Infinite:

- Aiton, E. J. "Introduction to analysis of the infinite. Book I. Transl. by John D. Blanton. (English)". zbMATH. Zbl 0657.01013.

- Shiu, P. (December 1990). "Introduction to analysis of the infinite (Book II), by Leonard Euler (translated by John D. Blanton)". The Mathematical Gazette. 74 (470): 392–393. doi:10.2307/3618156. JSTOR 3618156.

- Ştefănescu, Doru. "Euler, Leonhard Introduction to analysis of the infinite. Book I. Translated from the Latin and with an introduction by John D. Blanton". Mathematical Reviews. MR 1025504.

- ^ Demidov, S. S. (2005). Treatise on the differential calculus. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4. Retrieved 2015-11-12. In Grattan-Guinness 2005, pp. 191–198.

- ^ a b c Kleinert, Andreas (2015). "Leonhardi Euleri Opera omnia: Editing the works and correspondence of Leonhard Euler". Prace Komisji Historii Nauki PAU. 14. Jagiellonian University: 13–35. doi:10.4467/23921749pkhn_pau.16.002.5258.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard; Fuss, Nikola Ivanovich; Fuss, Paul (1862). Opera postuma mathematica et physica anno 1844 detecta quae Academiae scientiarum petropolitanae obtulerunt ejusque auspicus ediderunt auctoris pronepotes Paulus Henricus Fuss et Nicolaus Fuss. Imperatorskaia akademīia nauk (Russia). OCLC 9094558695.

- ^ Calinger 2016, pp. ix–x.

- ^ "The Eneström Index". Euler Archive. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ Knapp, Susan (19 February 2007). "Dartmouth students build online archive of historic mathematician". Vox of Dartmouth. Dartmouth College. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28.

- ^ Klyve, Dominic (June–July 2011). "Euler Archive Moves To MAA Website". MAA FOCUS. Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ "The Euler Archive". University of the Pacific.

- ^ a b Plüss, Matthias. "Der Goethe der Mathematik". Swiss National Science Foundation. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ^ Varadarajan, V. S. (2006). Euler through time: a new look at old themes. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-3580-7. OCLC 803144928.

- ^ Libri, Gugliemo (January 1846). "Correspondance mathématique et physique de quelques célèbres géomètres du XVIIIe siècle, ..." [Mathematical and physical correspondence of some famous geometers of the eighteenth century, ...]. Journal des Savants (in French): 51. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

Sources

[edit]- Calinger, Ronald (1996). "Leonhard Euler: The First St. Petersburg Years (1727–1741)". Historia Mathematica. 23 (2): 121–166. doi:10.1006/hmat.1996.0015.

- Calinger, Ronald (2016). Leonhard Euler: Mathematical Genius in the Enlightenment. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11927-4. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- Dunham, William (1999). Euler: The Master of Us All. Dolciani Mathematical Expositions. Vol. 22. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-328-3. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- Euler, Leonhard (1739). Tentamen novae theoriae musicae [An attempt at a new theory of music, exposed in all clearness, according to the most well-founded principles of harmony] (in Latin). St. Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2021-06-12 – via Euler archive.

- Ferraro, Giovanni (2008). The Rise and Development of the Theory of Series up to the Early 1820s. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-73467-5. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- Gekker, I. R.; Euler, A. A. (2007). "Leonhard Euler's family and descendants". In Bogolyubov, Nikolaĭ Nikolaevich; Mikhaĭlov, G. K.; Yushkevich, Adolph Pavlovich (eds.). Euler and Modern Science. Translated by Robert Burns. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-564-5. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- Gautschi, Walter (2008). "Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works". SIAM Review. 50 (1): 3–33. Bibcode:2008SIAMR..50....3G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.177.8766. doi:10.1137/070702710. ISSN 0036-1445. JSTOR 20454060.

- Grattan-Guinness, Ivor, ed. (2005). Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640–1940. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4.

- Richeson, David S. (2012). Euler's Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology. Princeton University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4008-3856-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Bradley, Robert E.; D'Antonio, Lawrence A.; Sandifer, Charles Edward (2007). Euler at 300: An Appreciation. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-565-2.

- Bradley, Robert E.; Sandifer, Charles Edward, eds. (2007). Leonhard Euler: Life, Work and Legacy. Studies in the History and Philosophy of Mathematics. Vol. 5. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-52728-8. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- Dunham, William (2007). The Genius of Euler: Reflections on his Life and Work. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-558-4.

- Hascher, Xavier; Papadopoulos, Athanase, eds. (2015). Leonhard Euler: Mathématicien, physicien et théoricien de la musique (in French). Paris: CNRS Editions. ISBN 978-2-271-08331-9. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- Sandifer, C. Edward (2007). The Early Mathematics of Leonhard Euler. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-559-1.

- Sandifer, C. Edward (2007). How Euler Did It. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-563-8.

- Sandifer, C. Edward (2015). How Euler Did Even More. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-584-3. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- Schattschneider, Doris, ed. (November 1983). "A Tribute to Leonhard Euler 1707–1783 (special issue)". Mathematics Magazine. 56 (5). JSTOR i326726.

External links

[edit]- Leonhard Euler at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- The Euler Archive: Composition of Euler works with translations into English

- Opera-Bernoulli-Euler (compiled works of Euler, Bernoulli family, and contemporary peers)

- Euler Tercentenary 2007

- The Euler Society

- Euleriana at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- Euler Family Tree

- Euler's Correspondence with Frederick the Great, King of Prussia

- Works by Leonhard Euler at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. "Leonhard Euler". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews.

- Dunham, William (24 September 2009). "An Evening with Leonhard Euler". YouTube. Muhlenberg College: philoctetesctr (published 9 November 2009). (talk given by William Dunham at )

- Dunham, William (14 October 2008). "A Tribute to Euler – William Dunham". YouTube. Muhlenberg College: PoincareDuality (published 23 November 2011).

.jpg/250px-Leonhard_Euler_-_Jakob_Emanuel_Handmann_(Kunstmuseum_Basel).jpg)

.jpg/1547px-Leonhard_Euler_-_Jakob_Emanuel_Handmann_(Kunstmuseum_Basel).jpg)