Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Eleven-plus

View on Wikipedia

| Purpose | Determining admission to selective secondary schools |

|---|---|

| Year started | 1944 |

| Offered | To Year Six/Year 6 Primary, Seven/Primary 7 school pupils |

| Restrictions on attempts | Single attempt |

| Regions | England and Northern Ireland |

| Fee | Free (England)[citation needed] £50 administration fee (Northern Ireland)[1] |

| Used by | Selective secondary schools |

The eleven-plus (11+) is a standardised examination administered to some students in England and Northern Ireland in their last year of primary education, which governs admission to grammar schools and other secondary schools that use academic selection. The name derives from the age group for secondary entry: 11–12 years.

The eleven-plus was once used throughout the UK, but is now only used in counties and boroughs in England that offer selective schools instead of comprehensive schools.[2] Also known as the transfer test, it is especially associated with the Tripartite System which was in use from 1944 until it was phased out across most of the UK by 1976.[3]

The examination tests a student's ability to solve problems using a test of verbal reasoning and non-verbal reasoning, and most tests now also offer papers in mathematics and English. The intention was that the eleven-plus should be a general test for intelligence (cognitive ability) similar to an IQ test, but by also testing for taught curriculum skills it is evaluating academic ability developed over previous years, which implicitly indicates how supportive home and school environments have been.[citation needed]

Introduced in 1944, the examination was used to determine which type of school the student should attend after primary education: a grammar school, a secondary modern school, or a technical school. The base of the Tripartite System was the idea that skills were more important than financial resources in determining what kind of schooling a child should receive: different skills required different schooling.

In some local education authorities the Thorne plan or scheme or system developed by Alec Clegg, named in reference to Thorne Grammar School, which took account of primary school assessment as well as the once-off 11+ examination, was later introduced.[4][5]

Within the Tripartite System

[edit]The Tripartite System of education, with an academic, a technical and a functional strand, was established in the 1940s. Prevailing educational thought at the time was that testing was an effective way to discover the strand to which a child was most suited. The results of the exam would be used to match children's secondary schools to their abilities and future career needs.

When the system was implemented, technical schools were not available on the scale envisaged. Instead, the Tripartite System came to be characterised by fierce competition for places at the prestigious grammar schools. As such, the eleven-plus took on a particular significance. Rather than allocating according to need or ability, it became seen as a question of passing or failing. This led to the exam becoming widely resented by some although strongly supported by others.[6]

Structure

[edit]The structure of the eleven-plus varied over time, and among the different counties which used it. Usually, it consisted of three papers:

- Arithmetic – A mental arithmetic test.

- Writing – An essay question on a general subject.

- General Problem Solving – A test of general knowledge, assessing the ability to apply logic to simple problems.

Some exams have:

- Verbal Reasoning

- Non-Verbal Reasoning

Most children took the eleven-plus in their final year of primary school: usually at age 10 or 11. In Berkshire and Buckinghamshire it was also possible to sit the test a year early – a process named the ten-plus; later, the Buckinghamshire test was called the twelve-plus and taken a year later than usual.

Originally, the test was voluntary; as of 2009[update], some 30% of students in Northern Ireland do not sit for it.[7]

In Northern Ireland, pupils sitting the exam were awarded grades in the following ratios: A (25%), B1 (5%), B2 (5%), C1 (5%), C2 (5%), D (55%). There was no official distinction between pass grades and fail grades.

Current practice

[edit]

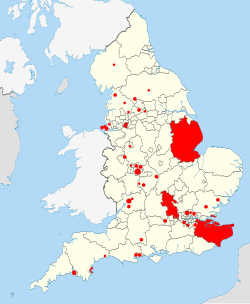

There are 163 remaining grammar schools in various parts of England, and 67 in Northern Ireland. In counties in which vestiges of the Tripartite System still survive, the eleven-plus continues to exist. Today it is generally used as an entrance test to a specific group of schools, rather than a blanket exam for all pupils, and is taken voluntarily. For more information on these, see the main article on grammar schools.

Eleven-plus and similar exams vary around the country but will use some or all of the following components:

- Verbal Reasoning (VR)

- Non-Verbal reasoning (NVR)

- Mathematics (MA)

- English (EN)

Eleven-plus tests take place in September of children's final primary school year with results provided to parents in October to allow application for secondary schools. In Lincolnshire children will sit the Verbal Reasoning and Non-Verbal Reasoning. In Buckinghamshire children sit tests in Verbal Reasoning, Mathematics and Non-Verbal reasoning. In Kent, where the eleven-plus test is more commonly known as the Kent Test, children sit all four of the above disciplines; however the Creative Writing, which falls as part the English test, will only be used in circumstances of appeal.[9] In the London Borough of Bexley from September 2008, following a public consultation, pupils sitting the Eleven-Plus exam are only required to do a Mathematics and Verbal Reasoning paper. In Essex, where the examination is optional, children sit Verbal Reasoning, Mathematics and English. Other areas use different combinations. Some authorities/areas operate an opt-in system, while others (such as Buckinghamshire) operate an opt-out system where all pupils are entered unless parents decide to opt out. In the North Yorkshire, Harrogate/York area, children are only required to sit two tests: Verbal and Non-Verbal Reasoning.

Independent schools in England generally select children at the age of 13, using a common set of papers known as the Common Entrance Examination.[10] About ten do select at eleven; using papers in English, Mathematics and Science. These also have the Common entrance exam name.[11]

Scoring

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (April 2023) |

| Authority/consortium | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Bishop Wordsworth | 100 | 15 |

| Chelmsford | 100 | 15 |

| Dover Grammar School for Boys | 100 | 15 |

| Folkestone | 100 | 15 |

| Gloucester | 100 | 15 |

| Harvey | 100 | 15 |

| Heckmondwike | 100 | 15 |

| Henrietta Barnett School | 100 | 15 |

| Kendrick School | 100 | 15 |

| Mayfield | 100 | 15 |

| Reading School | 100 | 15 |

| Redbridge | 100 | 15 |

| The Latymer School | 100 | 15 |

| Torbay and Devon Consortium | 100 | 15 |

| West Midland Boys | 100 | 15 |

| West Midland Girls | 100 | 15 |

| Buckinghamshire | 100 | 43 |

| Dame Alice Owen | 106 | 15 |

| Slough Consortium | 106 | 15 |

| South West Herts | 106 | 15 |

| Bexley | 200 | 30 |

| King Edwards Consortium | 200 | 30 |

| Warwickshire | 200 | 30 |

| Wirral Borough Council | 234 | 15 |

| Altrincham | 315 | 30 |

| Sale | 318 | 30 |

| Stretford | 327 | 30 |

| Urmston | 328 | 30 |

England has 163 grammar schools 155 of which control their own admissions including the choice of test. (143 Academy Converters, six Foundation schools and six Voluntary aided schools control their own admissions. Admissions for the remaining seven Community Schools and one Voluntary Controlled school are determined by the local authority.; [12] [13]

Over 95% of grammar schools now determine their own admissions policies, choosing what tests to set and how to weight each component. Although some form consortia with nearby schools to agree on a common test, there may be as many as 70 different 11+ tests set across the country [14] meaning it is not possible to refer to the eleven plus test as a single entity.

Tests are multiple choice. The number of questions varies but the guidance provided by GLA [15] shows that full length Maths and English Comprehension tests are both 50 minutes duration and consist of about 50 questions. Verbal Reasoning is 60 minutes containing 80 questions. Non-Verbal Reasoning is 40 minutes broken into four 10-minute separately-timed sections each containing 20 questions. At a rate of one question every 30 seconds, it could be argued that the test is one of speed rather than intelligence.

One mark is awarded for each correct answer. No marks are deducted for incorrect or un-attempted responses. [16] There are usually five possible answers, one of which is always correct meaning a random guess has a 20% chance of being correct and a strategy of guessing all un-attempted questions in the last few seconds of the exam will, if anything, gain the candidate a few additional marks which may make the difference needed to gain a place.

The actual marks from these tests, referred to as raw marks, are not disclosed by all schools, and instead parents are given Standard Age Scores (SAS). A standard score shows how well the individual has performed relative to the mean (average) score for the population although the term population is open to interpretation. GL Assessment, who set the majority of 11+ tests, say it should be, "a very large, representative sample of students usually across the UK";[17] however, grammar schools may standardise their tests against just those children who apply to them in a given year, as this enables them to match supply to demand.

Test results follow a normal distribution resulting in the familiar bell curve which reliably predicts how many test takers gain each different score. For example, only 15.866% score more than one standard deviation above the mean (+1σ generally represented as 115 SAS) as can be seen by adding up the proportions in this graph based on the original provided by M. W. Toews).

By standardising on just the cohort of applicants, a school with, for example, 100 places which regularly gets 800 applications can set a minimum pass mark of 115 which selects approximately 127 applicants filling all of the places and leaving about 27 on the waiting list. The downside of this local standardisation, as it has been called, is parents are frequently unaware that their children are being judged as much by the standard of other applicants as their own abilities.

Another issue with the lack of national standards in testing is it prevents any comparison between schools. Public perception may be that only pupils who are of grammar school standard are admitted to grammar schools; however, other information such as the DfE league tables[18][19] calls into question the existence of any such standard. Competition for places at Sutton Grammar School is extremely fierce with, according to an online forum[20] over 2,500 applicants in 2016. At the other end of the scale, Buckinghamshire council website says, "If your child's STTS is 121 or above, they qualify for grammar school. We expect that about 37% of children will get an STTS of 121 or more."[21] Official statistics show 100% of those admitted to Sutton Grammar School have, "high prior attainment at the end of key stage 2", compared to only 44% of those who attend Skegness Grammar School. The Grammar Schools Heads Association's Spring 2017 newsletter[22][23] says the government are considering a national selection test which would remove the lack of consistency between different 11+ tests.

Between them, GL (Granada Learning) and CEM (Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring) earn an estimated £2.5m annually[24] from setting and marking the 11+ tests. Releasing the raw marks would bring some clarity to the admissions process but attempts to do so have generally been unsuccessful. GL have used the fact that they are not covered by Freedom of Information legislation to withhold information[25] made for information relating to the 11+ exams used by Altrincham Grammar School for Boys, who stated, "Our examination provider, GL Assessment Limited (GL) is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOI) as it is not a public body.“, whilst their main rival CEM successfully argued in court[26][27] that, "one of the benefits of its 11+ testing is that it is 'tutor proof'” and releasing the raw marks would undermine this unique selling point.

When a standard score is calculated the results is a negative value for any values below the mean. As it would seem very strange to be given a negative score Goldstein and Fogelman (1974)[28] explain, "It is common to 'normalise' the scores by transforming them to give a distribution with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15."[29] Thus a normalised SAS of 100 indicates the mean (average) achievement whilst a score of 130 would be two standard deviations above the mean. A score achieved by only 2.2% of the population. Most, but not all, authorities normalise follow this convention. The following table[30] showing the normalisation values used by some for 2017 entry (tests taken in 2016).

Northern Ireland

[edit]The system in Northern Ireland differed from that in England. The last eleven-plus was held in November 2008.[31] A provision in the Education Order (NI) 1997 states that "the Department may issue and revise guidance as it thinks appropriate for admission of pupils to grant-aided schools". Citing this on 21 January 2008, Northern Ireland's Education Minister Caitríona Ruane passed new guidelines regarding post-primary progression as regulation rather than as legislation. This avoided the need for the proposals to be passed by the Northern Ireland Assembly, where cross-party support for the changes did not exist.[32][33] Some schools, parents and political parties object to the new legal framework. As a result, many post-primary schools are setting their own entrance examinations.

Controversy

[edit]

The 11-plus was a result of major changes which took place in English and Welsh education in the years up to 1944. In particular, the Hadow Report of 1926 called for the division of primary and secondary education to take place on the cusp of adolescence at 11 or 12. The implementation of this break by the Butler Act seemed to offer an ideal opportunity to implement streaming, since all children would be changing school anyway. Thus testing at 11 emerged largely as an historical accident, without other specific reasons for testing at that age.

The test, composed of Maths, English and Verbal Reasoning could not be passed by 10-year-olds who had not been trained for the test.[according to whom?] Martin Stephen a former High Master of Manchester Grammar School asserted on BBC Radio 4's The Moral Maze that no child who had not seen the verbal reasoning tests that formed the basis of the 11-plus before attempting them would have a "hope in hell" of passing them, and he had dispensed with the 11-plus as "worthless". Instead he used personal interviews.[34] Children in school were drilled in the 11-plus until it was "coming out of their ears".[citation needed] Families had to play the system, little booklets were available from local newsagents that showed how to pass the exam and contained many past papers with all the answers provided, which the children then learned by rote.[34]

Criticism of the 11-plus arose on a number of grounds, though many related more to the wider education system than to academic selection generally or the 11-plus specifically. The proportions of schoolchildren gaining a place at a grammar school varied by location and sex. 35% of pupils in the South West of England secured grammar school places as opposed to 10% in Nottinghamshire.[35] In some areas, because of the continuance of single-sex schooling in those areas, there were sometimes fewer places for girls than for boys. Some areas were coeducational and had equal number of places for each sex.

Critics of the 11-plus also claimed that there was a strong class bias in the exam. JWB Douglas, studying the question in 1957, found that children on the borderline of passing were more likely to get grammar school places if they came from middle-class families.[36] For example, questions about the role of household servants or classical composers were far easier for middle-class children to answer than for those from less wealthy or less educated backgrounds.[citation needed] In response, the 11-plus was redesigned during the 1960s to be more like an IQ test. However, even after this modification, grammar schools were largely attended by middle-class children while secondary modern schools were attended by mostly working-class children.[37][38][39] By testing cognitive skills the child's innate ability is evaluated as a predictor to future academic performance and is largely independent of background and support [citation needed]. The problem lies with the testing of academic subjects, such as Maths and English, where a child from a working class background with a less supportive school and less educated parents is being measured on their learning environment instead of potential to succeed [citation needed].

Passing – or not passing – the 11-plus was a "defining moment in many lives", with education viewed as "the silver bullet for enhanced social mobility."[40] Richard Hoggart claimed in 1961 that "what happens in thousands of homes is that the 11-plus examination is identified in the minds of parents, not with 'our Jimmy is a clever lad and he's going to have his talents trained', but 'our Jimmy is going to move into another class, he's going to get a white-collar job' or something like that."[41]

References

[edit]- ^ https://seagni.co.uk/ [bare URL]

- ^ Adams, Richard (6 September 2024). "English grammar schools raising funds with charge for mock 11-plus exam". The Guardian.

- ^ Moonsammy, Ashminnie (7 May 2025). "Education officials fan out for 11-Plus exams". nationnews.com.

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (7 December 1999). "The great grammar divide". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ "Medway: Parents raise concerns over this year's 11-plus exam". www.bbc.com. 19 September 2024.

- ^ Fletcher, Tony (1998). Dear Boy: The Life of Keith Moon. Omnibus Press. pp. 9, 11. ISBN 978-1-84449-807-9.

- ^ "Transfer Procedure – Department of Education, Northern Ireland". Deni.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ The Education (Grammar School Ballots) Regulations 1998, Statutory Instrument 1998 No. 2876, UK Parliament.

- ^ "Kent Test Guidance". How2Become.

- ^ "Common Entrance at 13+". www.iseb.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ "Common Entrance at 11+". www.iseb.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ DfE Schools Pupils and Characteristics datasetSchool level data. Department for Education.

- ^ West, Anne and David Wolfe. Academies, autonomy, equality and democratic accountability: Reforming the fragmented publicly funded school system in England. London Review of Education (2019)

- ^ CEM set tests for 28 different LAs, consortia and individual schools and claim to have 40% of the market. Extrapolating would suggest there are approx. 70 different sets of tests in total.

- ^ Free familiarisation materials[1]. Granada Learning Assessment (GLA).

- ^ Freedom of Information[2]. Buckinghamshire Grammar Schools.

- ^ GL Assessment A short guide to standardised tests. 013 GL Assessment Limited.

- ^ "Download data – GOV.UK – Find and compare schools in England". Find and compare schools in England.

- ^ Data source: England_ks4final.csv. Field 39, PTPRIORHI shows the Percentage of pupils at the end of key stage 4 with high prior attainment at the end of key stage 2.

- ^ "11 plus Surrey, Grammar School Admissions". www.elevenplusexams.co.uk.

- ^ Marking the Secondary Transfer Test[3]. Buckinghamshire Council.

- ^ "GSHA Newsletter" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2018.

- ^ "The Grammar Schools Heads Association's website went offline in early July 2017 but a copy of their Spring newsletter is still available from Schools Week's website" (PDF).

- ^ Coombs v Information Commissioner, EA/2015/0226, 22 April 2016, p. 11. CEM told the Information Commissioner they earn £1m from 40% of the market making £2.5m a reasonable estimate for 100% of the market.

- ^ "Request for report on 11+ exam – a Freedom of Information request to Altrincham Grammar School For Boys". 23 May 2016.

- ^ "Case no. EA/2015/0226" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2020.

- ^ Coombs v Information Commissioner (ibid), p. 5.

- ^ "Age standardisation and seasonal effects in mental testing" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 May 2015.

- ^ "Goldstein H and Fogelman K, 1974, Age standardisation and seasonal effects in mental testing. Downloaded from /www.bristol.ac.uk" (PDF).

- ^ "CEM 11+ test results 2014 – 2016. – a Freedom of Information request to Durham University". 6 October 2016.

- ^ "Future uncertain as 11-plus ends". BBC News Online. 21 November 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- ^ Anne Murray (3 February 2009). "Ruane urged to publish legal advice on transfer plans – Education, News". Belfasttelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ "The tricky path from peace to harmony". Public Service. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ a b Horrie, Chris (4 May 2017). "Grammar schools: back to the bad old days of inequality". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Szreter, S. Lecture, University of Cambridge, Lent Term 2004.

- ^ Sampson, A. Anatomy of Britain Today, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1965, p. 195.

- ^ Hart, R.A., Moro M., Roberts J.E., 'Date of birth, family background, and the Eleven-Plus exam: short- and long-term consequences of the 1944 secondary education reforms in England and Wales', Stirling Economics Discussion Paper 2012-10 May 2012 pp. 6 to 25. "Working Papers". Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "Reflecting Education". reflectingeducation.net.

- ^ Sampson, A., Anatomy of Britain Today, Hodder and Stoughton, 1965, pp. 194–195.

- ^ David Kynaston, Modernity Britain: A Shake of the Dice 1959–62, Bloomsbury, 2014, pp.179–182.

- ^ Kynaston, p. 192.

External links

[edit]- Taylor, Matthew (28 July 2005). "PAT, dissenting teaching union, calls for return of 11-plus". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Beckett, Francis (15 October 2002). "Not so special after all". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Baker, Mike (15 February 2003). "What future for grammar schools?". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "School admissions 'socially divisive'". BBC News. 31 January 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "State schools 'failing brightest pupils'". The Guardian. 23 May 2005. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

Eleven-plus

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Development

The selective entrance examinations that foreshadowed the eleven-plus originated in the early 20th century, when grammar schools in England and Wales admitted pupils primarily through fee-paying places or competitive scholarships awarded via tests administered around age 11, often focusing on arithmetic, English, and general intelligence measures; however, these were not standardized nationally and access remained limited to a small proportion of children, with many grammar schools drawing disproportionately from middle-class families able to afford preparatory coaching or direct fees.[12][13] The Education Act 1944, also known as the Butler Act, marked the formal origin of the eleven-plus as a nationwide selection mechanism, mandating free secondary education for all children and establishing a tripartite system of grammar schools for the academically able, technical schools for those suited to applied sciences, and secondary modern schools for the majority; selection was to occur at age 11 through a standardized examination designed to allocate approximately 20-25% of pupils to grammar schools based on perceived innate ability.[14][15] The eleven-plus exam's design drew from contemporary psychological research on intelligence testing, incorporating elements like verbal reasoning, arithmetic, and composition to approximate IQ assessments, with contributions from figures such as Cyril Burt, who during World War II collaborated on prototypes aimed at efficient pupil classification amid postwar reconstruction; initial implementations from 1945 onward varied by local education authorities, but by the late 1940s, most areas adopted a core format of two or three papers testing innate rather than coached abilities, though technical schools largely failed to materialize, concentrating selection pressure on grammar places.[16][17] In Northern Ireland, where the Act's principles were adapted, the exam was introduced in 1947 as a transfer test to grammar schools, achieving near-universal application by 1950 and influencing cross-border practices.[18] Early development revealed inconsistencies, such as regional variations in pass marks and emerging evidence of birth-month biases favoring summer-born children due to relative age effects within year groups, prompting minor adjustments like age allowances in scoring by the 1950s, yet the core principle of ability-based streaming persisted without fundamental overhaul until the 1960s.[12][15]Implementation in the Tripartite System

The Education Act 1944 empowered local education authorities (LEAs) to organize secondary education into a tripartite structure of grammar, technical, and secondary modern schools, with provision for selection at age 11 based on ability and aptitude to ensure education suited to each child's needs.[14] Although the Act did not mandate a specific selection mechanism or rigidly prescribe the tripartite model, LEAs increasingly adopted the 11-plus examination as the tool for allocating pupils, drawing on pre-war recommendations from reports like Spens (1938) and Norwood (1943) that advocated differentiated schooling.[19] This exam, typically comprising verbal reasoning, non-verbal reasoning, arithmetic, and English components, was first trialed in some areas during the early 1940s but rolled out nationally post-war, with widespread implementation by 1947 as LEAs built or repurposed schools to accommodate the system.[15] In practice, the 11-plus determined entry to grammar schools for the estimated top 15-25% of pupils, depending on local quotas set by LEAs to match available places, while the remainder attended secondary modern schools; technical schools, intended for those with practical or technical aptitudes, were established in only a small fraction of areas, enrolling fewer than 5% of pupils by the 1950s due to funding constraints and shifting priorities.[20][21] Selection aimed to identify innate academic potential through standardized testing, with pass marks adjusted locally—often around 80-90% in aggregate scores—to fill grammar school capacities, which by 1950 served approximately 20% of the secondary cohort in most English LEAs.[22] The Ministry of Education provided guidance on test design and moderation to minimize regional disparities, but implementation remained decentralized, leading to variations in exam formats and appeal processes for borderline cases.[23] By the mid-1950s, the tripartite system via 11-plus selection was entrenched across England and Wales, with over 1,200 grammar schools operational and secondary moderns absorbing the majority; however, technical provision lagged, comprising just 200 schools nationwide by 1960, as LEAs prioritized grammar and modern expansions amid post-war reconstruction.[19] This structure reflected an empirical commitment to ability-based differentiation, though early data indicated inconsistencies in test reliability across socioeconomic groups, prompting LEA adjustments like additional interviews or retests in some districts.[15] The system's rollout emphasized free provision up to age 15, funded centrally with LEA discretion, achieving near-universal secondary coverage by 1952.[14]Decline and Regional Persistence

The Eleven-plus examination experienced a marked national decline after the Department of Education and Science issued Circular 10/65 on 12 July 1965, which instructed local education authorities to prepare plans for comprehensive secondary schooling and end selection by ability at age 11.[24] This policy shift accelerated the closure or conversion of grammar schools, with their numbers falling from a peak of 1,298 in 1964—a figure representing about 25% of state secondary pupils—to far fewer as most authorities adopted non-selective systems by the late 1970s.[25][26] Subsequent measures reinforced the trend: the proportion of pupils in grammar schools dropped below 20% in the early 1970s, under 10% by the mid-1970s, and stabilized at approximately 5% from the late 1970s, reflecting the dominance of comprehensive education across England, Wales, and Scotland.[26] In England, the remaining grammar schools—numbering around 163 by the 1980s—were protected from further reduction by the Education Act 1996, which banned new state grammars unless approved via parental ballot, a threshold unmet since 1998.[27] This stabilization occurred despite ongoing debates over the exam's role in perpetuating social selection, as evidenced by pass rates hovering at 20-25% in selective areas amid criticisms of coaching advantages.[28] Regional persistence endures in England, where 163 grammar schools operate in 36 of 151 local authorities, serving roughly 5% of secondary pupils through Eleven-plus testing.[5] Selective systems remain intact in counties like Kent (fully selective), Buckinghamshire, Lincolnshire, and Trafford, and in London boroughs including Bexley, Bromley, Sutton, and Kingston upon Thames, where local ballots have upheld grammar provision.[29] In Northern Ireland, academic selection via the Transfer Test—equivalent to the Eleven-plus—continues for entry to over 60 grammar schools, with more than 10,000 pupils receiving results annually for Year 8 admissions as of January 2025.[30] Though the formal Eleven-plus ended in 2009 following reviews highlighting inequality, private providers like the Association for Quality Education have sustained standardized testing, resisting full abolition despite periodic reform proposals.[31] Wales and Scotland maintain no state grammar schools, having fully transitioned to comprehensives by the 1980s.[25]Examination Design

Test Components and Format

The eleven-plus examination typically assesses pupils' abilities in English, mathematics, verbal reasoning, and non-verbal reasoning through timed papers designed to evaluate both academic knowledge and cognitive skills. These components aim to identify suitability for selective grammar school education, with content drawn from the national curriculum up to Year 5 level alongside reasoning tasks that test problem-solving independent of taught material.[6][32] Formats differ significantly by provider or consortium, reflecting regional consortia preferences in England. GL Assessment tests, common in areas like Birmingham and Warwickshire, use separate papers per subject—verbal reasoning, non-verbal reasoning, mathematics, and English—with multiple-choice questions answered on a scannable sheet; each paper lasts 45 to 50 minutes and contains around 80 to 100 questions, emphasizing speed and accuracy under time constraints.[33][34] In contrast, CEM Select exams, utilized in regions such as Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire and developed by Durham University's Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring, consist of two 50-minute papers mixing subjects: one combining mathematics and non-verbal reasoning, the other English and verbal reasoning; questions employ varied formats including short-answer, cloze, and comprehension without multiple-choice options, with internally timed sections to prevent over-reliance on coaching.[35][36][37] The Consortium for Selective Schools in Essex (CSSE) adopts a curriculum-focused structure with two 50-minute papers dedicated to English (including comprehension, vocabulary, and composition elements) and mathematics, respectively, using standard written responses rather than multiple choice or heavy reasoning; this format prioritizes depth in core subjects over abstract puzzles, aligning more closely with school-based testing.[38] Some independent or hybrid providers, like ISEB for pre-prep entry, offer computer-adaptive online formats, but these are less common for state grammar selections. Across providers, exams are paper-based unless specified otherwise, administered in supervised venues in September of Year 6, with no calculators permitted and emphasis on unaided recall.[39] Variations may include practice or familiarization elements, but core components remain consistent in targeting age-standardized performance around the 11-year mark.[40]Scoring Mechanisms

The Eleven-plus examination utilizes standardized age scores (SAS) derived from raw marks to account for variations in candidates' ages within the testing cohort, typically children aged 10 to 11 in their final primary school year. Raw scores, representing the number of correct answers, are converted using statistical norms where the mean score is set at 100 and the standard deviation at 15, akin to intelligence quotient scaling; this adjustment ensures younger candidates are not disadvantaged compared to those closer to their 11th birthday.[41][42][43] Scoring mechanisms vary by exam provider, with GL Assessment employing separate SAS for subjects like verbal reasoning, non-verbal reasoning, mathematics, and English, often aggregated into a total score for selection. In contrast, the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring (CEM) typically combines raw scores from multiple papers into a single standardized total, such as out of a maximum adjusted scale around 121, without always providing subject breakdowns to reduce coaching predictability.[34][44] Grammar schools or consortia determine pass thresholds or cut-off scores annually based on applicant numbers and available places, rather than a fixed national standard; for instance, many require an aggregate SAS of 110 or higher, though competitive areas may demand 115–121 to qualify.[41][45][46] Some regions, like certain English counties, apply additional weighting or minimum sub-scores per section to prevent imbalances from overperformance in one area.[47]| Provider | Scoring Approach | Typical Aggregation | Example Pass Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| GL Assessment | Subject-specific SAS (mean 100, SD 15), age-adjusted | Summed total SAS | 110+ aggregate[42][34] |

| CEM | Combined raw-to-standardized total | Single scaled score (e.g., up to 121) | 110–121, school-set[44] |

Preparation and Coaching Influences

Preparation for the eleven-plus examination typically involves a combination of school-based instruction, parental guidance, and private tutoring, with the latter becoming increasingly prevalent in areas retaining selective grammar schools. In regions such as Kent and Buckinghamshire, where grammar school entry depends on the exam, up to 40% of candidates reportedly receive private tuition, often starting 12-18 months in advance to familiarize children with verbal reasoning, non-verbal reasoning, mathematics, and English components.[50] This coaching market, valued at billions annually in the UK, targets skills like pattern recognition and vocabulary expansion, which are not always emphasized in standard primary curricula.[51] Empirical research indicates that coaching yields measurable score gains, though the magnitude and persistence vary. A study administering parallel test forms found that short-term coaching (approximately three hours) produced a small but statistically significant improvement in performance, equivalent to a few percentile points, while extended practice further elevated scores without substantially altering candidates' relative rankings.[52] However, these gains appear to reflect enhanced test familiarity rather than deepened underlying ability, as coached pupils from affluent backgrounds often underperform relative to expectations at later key stages like GCSE, suggesting inflated early assessments.[51] Coaching exacerbates socioeconomic disparities in access to grammar schools, as families with greater financial resources—typically higher-income households—can afford specialized tuition costing £20-£50 per hour, disadvantaging lower-income candidates who rely solely on free school preparation. In Buckinghamshire, for instance, pass rates hover around 20% for state primary pupils versus 70% for those from independent schools, where intensive coaching is routine, despite efforts to design "tutor-proof" tests.[53] This pattern aligns with broader data showing grammar school intakes skewed toward higher socioeconomic groups, with private tutoring correlating to a 10-15% higher likelihood of selection after controlling for prior attainment.[54] Such influences undermine claims of meritocratic selection, as coaching effectively functions as a paid advantage in cognitive test preparation, with limited evidence of long-term academic benefits justifying the early streaming.[51]Current Implementation

Practice in England

In England, the eleven-plus examination serves as the primary mechanism for admitting pupils to the 163 state-funded grammar schools, which enroll about 188,000 secondary pupils or roughly 5% of the state sector.[55] These institutions are distributed across 35 local authorities, with concentrations in areas such as Kent (38 schools), Buckinghamshire, and Trafford, where selection rates can reach one in four or five children.[56][57] Fully selective systems operate in 11 authorities including Bexley, Kent, Lincolnshire, Medway, Slough, Southend-on-Sea, Sutton, Torbay, Trafford, and parts of Wiltshire, while others maintain partial selectivity alongside comprehensives.[5] The examination lacks a national standard, with formats determined by local consortia, individual schools, or providers like GL Assessment (used by over 80% of grammar schools) and, to a lesser extent, CEM from Durham University.[6] GL tests typically comprise multiple-choice or short-answer questions in English, mathematics, verbal reasoning, and non-verbal reasoning, administered over one or two sessions in early September for Year 7 entry the following academic year.[39] CEM assessments emphasize comprehension, vocabulary, and numerical/spatial reasoning with a focus on less coachable content, though CEM announced a shift to online delivery in late 2022, affecting some regions.[44] Shared tests occur in consortia, such as the one covering Warwickshire, Birmingham, Walsall, Wolverhampton, and Shropshire grammar schools.[58] Registration for the tests generally opens in June and closes by mid-July, with results released in October to align with secondary school applications via local authority coordinated schemes.[59] Qualification thresholds vary; for instance, Buckinghamshire requires a standardized score of at least 121 across combined papers, placing candidates in the top 25-30% nationally, while other areas adjust for local competition.[60] Successful candidates receive offers based on ranked scores, sibling priorities, and distance tie-breakers, though oversubscription panels and appeals processes allow for independent reviews of marking or suitability.[61] Participation is voluntary but competitive, with around 40-50% of eligible pupils in selective areas sitting the exam annually, influenced by parental choice and primary school encouragement.[32] Despite national policy prohibiting new grammar schools since 1998, existing ones maintain the practice, serving pupils from diverse backgrounds though access disparities persist by socioeconomic status.[55]Practice in Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, the state-administered 11-plus examination was formally abolished in 2009 following legislative changes aimed at reducing academic selection at age 11, yet grammar schools—numbering 66 out of 193 post-primary institutions—have maintained selective admissions through privately organized transfer tests.[62][63] The Schools' Entrance Assessment Group (SEAG), formed by a consortium of grammar schools, now administers a standardized transfer test used by the majority of these institutions as the principal criterion for Year 8 entry, with results determining eligibility based on performance relative to the cohort.[64][65] This system effectively replicates the selective function of the former 11-plus, channeling approximately 37-43% of pupils into grammar schools annually, though exact proportions vary by year and intake.[66][67] The SEAG transfer test, typically sat in the autumn term of Primary 7 (age 10-11), consists of two scored components following an unscored practice section: an English paper with 28 questions (22 multiple-choice on comprehension, spelling, and grammar; 6 requiring short written responses) and a mathematics paper with 56 multiple-choice questions covering topics such as number operations, measurement, shape, data handling, and problem-solving aligned to the Key Stage 2 curriculum.[68][69] The test is conducted under timed conditions, lasting about 90 minutes per paper, and is available in both paper and onscreen formats at designated centers, with accommodations for pupils with disabilities or those educated abroad.[70] Results are issued in January, providing a Total Standardised Age Score (TSAS) that aggregates standardized scores from English (or Irish) and mathematics, normalized to a mean of 100 with a standard deviation of 15 to account for age differences within the cohort.[71][72] Grammar schools rank applicants primarily by TSAS, often setting thresholds equivalent to Band 1 (top 40% of performers, or cohort percentile rank of 60% or higher) for admission, though some apply additional criteria such as siblings, residence, or special circumstances if oversubscribed.[73][74] Parents submit preferences for up to five post-primary schools via the Education Authority's online portal by mid-January, with allocations determined by school-specific criteria published annually; non-grammar options must be included to ensure placement.[62][75] Participation rates exceed 70% of the year group, driven by parental choice and the perceived academic advantages of grammar education, though private tutoring is widespread, potentially influencing outcomes for up to 50% of test-takers.[67] During the 2020-2021 academic year, COVID-19 disruptions led to test cancellation and reliance on alternative selectors like primary school reports, but the SEAG framework resumed thereafter without substantive reform.[76]Variations by Exam Providers

The primary providers of 11+ examinations for grammar school entry in England are GL Assessment and the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring (CEM), with GL used by over 80% of grammar schools as of 2025.[6] These providers differ in test format, content emphasis, and design philosophy, reflecting efforts to balance assessment of curriculum knowledge against reasoning skills and to mitigate advantages from private coaching.[77] [78] GL Assessment tests typically consist of four distinct papers covering English, mathematics, verbal reasoning, and non-verbal or spatial reasoning, administered as separate timed sections or combined into two papers.[79] [80] Questions align closely with the national primary curriculum up to Year 6, using multiple-choice formats scored electronically, with past papers and practice materials publicly available, which facilitates preparation through tutoring.[81] This structure is employed in regions such as Kent, Lincolnshire, and parts of the North West, where local authorities standardize tests across multiple schools.[82] In contrast, CEM exams, used in areas including Birmingham, Warwickshire, Buckinghamshire, and Durham, feature two papers combining verbal reasoning (including comprehension and vocabulary), numerical reasoning, and non-verbal reasoning, without dedicated English or mathematics sections.[83] [84] CEM deliberately avoids publishing past papers to reduce coachability, emphasizing innate reasoning over rote learning or curriculum-specific drills, with questions designed to be "tutor-proof" through novel formats and adaptive difficulty in some implementations.[85] [86] Scoring converts raw marks to age-standardized scores, often requiring higher thresholds (e.g., 121+ out of 141 in some consortia) due to the test's focus on differentiation at the upper ability range.[39] Other variations occur through independent consortia or local providers, such as the Consortium for Selective Schools in Essex (CSSE), which uses non-multiple-choice papers testing comprehension, vocabulary, mathematics, and an original writing task, without reasoning components.[87] Medway in Kent employs a similar GL-aligned but locally adapted format with multiple-choice and short-answer elements.[88] These bespoke tests prioritize creative and applied skills but maintain selective pass rates around 20-25% to limit grammar school intake.[89] Providers like ISEB are more common for independent schools and less relevant to state grammar selection.[81]Empirical Evidence of Outcomes

Academic Attainment Data

In England, grammar school pupils consistently achieve higher GCSE results than those in non-selective comprehensive schools, with raw attainment metrics showing substantial gaps attributable in part to the selective intake process based on 11+ performance. For instance, grammar school pupils obtain an average of 50.9 points per GCSE (where A* = 60, A = 50, down to G = 10), compared to 47.1 points in non-grammar schools, equating to roughly 0.5 to 1 grade advantage per subject.[90] After controlling for prior attainment at Key Stage 2, grammar pupils still secure approximately one-third of a grade higher across eight GCSEs than demographically similar pupils in comprehensives.[91] A systematic review of 32 quantitative studies confirms a small to moderate positive effect, with grammar attendees gaining 2.3 additional GCSE grade points over comparable comprehensive pupils, though non-grammar pupils in selective areas lag by 0.6 points.[92] A-level outcomes similarly favor grammar schools, where pupils outperform comprehensive peers after adjusting for GCSE entry qualifications, though value-added analyses indicate the premium diminishes when fully accounting for intake quality.[90] These patterns hold across multiple datasets, including the Pupil Level Annual School Census (PLASC) and National Pupil Database, using methods like regression discontinuity and propensity score matching to isolate school effects from selection biases.[90][92] In Northern Ireland, where the 11+ system applies more broadly to classify pupils into grammar and non-grammar (secondary) schools, attainment disparities are stark. In 2018/19, 94.3% of grammar school leavers achieved five or more GCSEs at A*-C (including English and Mathematics), compared to 51% in non-grammar schools.[93] At A-level, 63% of grammar pupils attained three or more qualifications at A*-C, versus 22% in non-grammar schools.[93] These figures, drawn from official Department of Education statistics, reflect systemic outcomes where grammar schools capture nearly all high-11+ performers, yielding elevated benchmarks despite controls for socioeconomic factors in multi-level regressions.[93]| Metric (2018/19) | Grammar Schools | Non-Grammar Schools |

|---|---|---|

| 5+ GCSEs A*-C (incl. Eng/Maths) | 94.3% | 51% |

| 3+ A-levels A*-C | 63% | 22% |