Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Standard score

View on Wikipedia

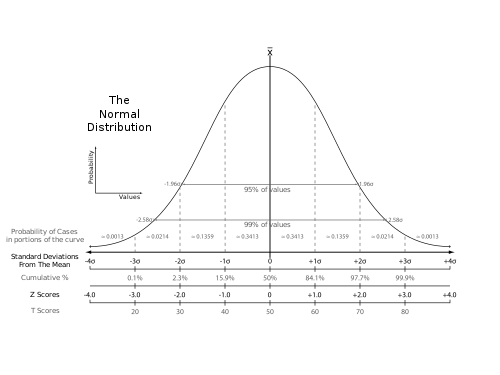

In statistics, the standard score or z-score is the number of standard deviations by which the value of a raw score (i.e., an observed value or data point) is above or below the mean value of what is being observed or measured. Raw scores above the mean have positive standard scores, while those below the mean have negative standard scores.

It is calculated by subtracting the population mean from an individual raw score and then dividing the difference by the population standard deviation. This process of converting a raw score into a standard score is called standardizing or normalizing (however, "normalizing" can refer to many types of ratios; see Normalization for more).

Standard scores are most commonly called z-scores; the two terms may be used interchangeably, as they are in this article. Other equivalent terms in use include z-value, z-statistic, normal score, standardized variable and pull in high energy physics.[1][2]

Computing a z-score requires knowledge of the mean and standard deviation of the complete population to which a data point belongs; if one only has a sample of observations from the population, then the analogous computation using the sample mean and sample standard deviation yields the t-statistic.

Calculation

[edit]If the population mean and population standard deviation are known, a raw score x is converted into a standard score by[3]

where:

- μ is the mean of the population,

- σ is the standard deviation of the population.

The absolute value of z represents the distance between that raw score x and the population mean in units of the standard deviation. z is negative when the raw score is below the mean, positive when above.

Calculating z using this formula requires use of the population mean and the population standard deviation, not the sample mean or sample deviation. However, knowing the true mean and standard deviation of a population is often an unrealistic expectation, except in cases such as standardized testing, where the entire population is measured.

When the population mean and the population standard deviation are unknown, the standard score may be estimated by using the sample mean and sample standard deviation as estimates of the population values.[4][5][6][7]

In these cases, the z-score is given by

where:

- is the mean of the sample,

- S is the standard deviation of the sample.

Though it should always be stated, the distinction between use of the population and sample statistics often is not made. In either case, the numerator and denominator of the equations have the same units of measure so that the units cancel out through division and z is left as a dimensionless quantity.

Applications

[edit]Z-test

[edit]The z-score is often used in the z-test in standardized testing – the analog of the Student's t-test for a population whose parameters are known, rather than estimated. As it is very unusual to know the entire population, the t-test is much more widely used.

Prediction intervals

[edit]The standard score can be used in the calculation of prediction intervals. A prediction interval [L,U], consisting of a lower endpoint designated L and an upper endpoint designated U, is an interval such that a future observation X will lie in the interval with high probability , i.e.

For the standard score Z of X it gives:[8]

By determining the quantile z such that

it follows:

Process control

[edit]In process control applications, the Z value provides an assessment of the degree to which a process is operating off-target.

Comparison of scores measured on different scales: ACT and SAT

[edit]

When scores are measured on different scales, they may be converted to z-scores to aid comparison. Dietz et al.[9] give the following example, comparing student scores on the (old) SAT and ACT high school tests. The table shows the mean and standard deviation for total scores on the SAT and ACT. Suppose that student A scored 1800 on the SAT, and student B scored 24 on the ACT. Which student performed better relative to other test-takers?

| SAT | ACT | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1500 | 21 |

| Standard deviation | 300 | 5 |

The z-score for student A is

The z-score for student B is

Because student A has a higher z-score than student B, student A performed better compared to other test-takers than did student B.

Percentage of observations below a z-score

[edit]Continuing the example of ACT and SAT scores, if it can be further assumed that both ACT and SAT scores are normally distributed (which is approximately correct), then the z-scores may be used to calculate the percentage of test-takers who received lower scores than students A and B.

Cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling

[edit]"For some multivariate techniques such as multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis, the concept of distance between the units in the data is often of considerable interest and importance… When the variables in a multivariate data set are on different scales, it makes more sense to calculate the distances after some form of standardization."[10]

Principal components analysis

[edit]In principal components analysis, "Variables measured on different scales or on a common scale with widely differing ranges are often standardized."[11]

Relative importance of variables in multiple regression: standardized regression coefficients

[edit]Standardization of variables prior to multiple regression analysis is sometimes used as an aid to interpretation.[12] (page 95) state the following.

"The standardized regression slope is the slope in the regression equation if X and Y are standardized … Standardization of X and Y is done by subtracting the respective means from each set of observations and dividing by the respective standard deviations … In multiple regression, where several X variables are used, the standardized regression coefficients quantify the relative contribution of each X variable."

However, Kutner et al.[13] (p 278) give the following caveat: "… one must be cautious about interpreting any regression coefficients, whether standardized or not. The reason is that when the predictor variables are correlated among themselves, … the regression coefficients are affected by the other predictor variables in the model … The magnitudes of the standardized regression coefficients are affected not only by the presence of correlations among the predictor variables but also by the spacings of the observations on each of these variables. Sometimes these spacings may be quite arbitrary. Hence, it is ordinarily not wise to interpret the magnitudes of standardized regression coefficients as reflecting the comparative importance of the predictor variables."

Standardizing in mathematical statistics

[edit]In mathematical statistics, a random variable X is standardized by subtracting its expected value and dividing the difference by its standard deviation

If the random variable under consideration is the sample mean of a random sample of X:

then the standardized version is

- Where the standardised sample mean's variance was calculated as follows:

T-score

[edit]In educational assessment, T-score is a standard score Z shifted and scaled to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.[14][15][16] It is also known as hensachi in Japanese, where the concept is much more widely known and used in the context of high school and university admissions.[17]

In bone density measurement, the T-score is the standard score of the measurement compared to the population of healthy 30-year-old adults, and has the usual mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mulders, Martijn; Zanderighi, Giulia, eds. (2017). 2015 European School of High-Energy Physics: Bansko, Bulgaria 02 - 15 Sep 2015. CERN Yellow Reports: School Proceedings. Geneva: CERN. ISBN 978-92-9083-472-4.

- ^ Gross, Eilam (2017-11-06). "Practical Statistics for High Energy Physics". CERN Yellow Reports: School Proceedings. 4/2017: 165–186. doi:10.23730/CYRSP-2017-004.165.

- ^ E. Kreyszig (1979). Advanced Engineering Mathematics (Fourth ed.). Wiley. p. 880, eq. 5. ISBN 0-471-02140-7.

- ^ Spiegel, Murray R.; Stephens, Larry J (2008), Schaum's Outlines Statistics (Fourth ed.), McGraw Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-148584-5

- ^ Mendenhall, William; Sincich, Terry (2007), Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences (Fifth ed.), Pearson / Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0131877061

- ^ Glantz, Stanton A.; Slinker, Bryan K.; Neilands, Torsten B. (2016), Primer of Applied Regression & Analysis of Variance (Third ed.), McGraw Hill, ISBN 978-0071824118

- ^ Aho, Ken A. (2014), Foundational and Applied Statistics for Biologists (First ed.), Chapman & Hall / CRC Press, ISBN 978-1439873380

- ^ E. Kreyszig (1979). Advanced Engineering Mathematics (Fourth ed.). Wiley. p. 880, eq. 6. ISBN 0-471-02140-7.

- ^ Diez, David; Barr, Christopher; Çetinkaya-Rundel, Mine (2012), OpenIntro Statistics (Second ed.), openintro.org

- ^ Everitt, Brian; Hothorn, Torsten J (2011), An Introduction to Applied Multivariate Analysis with R, Springer, ISBN 978-1441996497

- ^ Johnson, Richard; Wichern, Wichern (2007), Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis, Pearson / Prentice Hall

- ^ Afifi, Abdelmonem; May, Susanne K.; Clark, Virginia A. (2012), Practical Multivariate Analysis (Fifth ed.), Chapman & Hall/CRC, ISBN 978-1439816806

- ^ Kutner, Michael; Nachtsheim, Christopher; Neter, John (204), Applied Linear Regression Models (Fourth ed.), McGraw Hill, ISBN 978-0073014661

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ John Salvia; James Ysseldyke; Sara Witmer (29 January 2009). Assessment: In Special and Inclusive Education. Cengage Learning. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-0-547-13437-6.

- ^ Edward S. Neukrug; R. Charles Fawcett (1 January 2014). Essentials of Testing and Assessment: A Practical Guide for Counselors, Social Workers, and Psychologists. Cengage Learning. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-1-305-16183-2.

- ^ Randy W. Kamphaus (16 August 2005). Clinical Assessment of Child and Adolescent Intelligence. Springer. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-0-387-26299-4.

- ^ Goodman, Roger; Oka, Chinami (2018-09-03). "The invention, gaming, and persistence of the hensachi ('standardised rank score') in Japanese education". Oxford Review of Education. 44 (5): 581–598. doi:10.1080/03054985.2018.1492375. ISSN 0305-4985. JSTOR 26836035.

- ^ "Bone Mass Measurement: What the Numbers Mean". NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center. National Institute of Health. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Carroll, Susan Rovezzi; Carroll, David J. (2002). Statistics Made Simple for School Leaders (illustrated ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-4322-6. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- Larsen, Richard J.; Marx, Morris L. (2000). An Introduction to Mathematical Statistics and Its Applications (Third ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 282. ISBN 0-13-922303-7.

External links

[edit]Standard score

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A standard score, commonly referred to as a z-score, quantifies the position of a raw score relative to the mean of its distribution by expressing the deviation in units of standard deviation. It transforms an original value into a standardized form that allows for meaningful comparisons across diverse datasets or measurement scales.[2] The formula for a standard score in a population is given by where represents the raw score, denotes the population mean, and indicates the population standard deviation. When these population parameters are unavailable, sample-based estimates substitute in: the sample mean for and the sample standard deviation for . By construction, standard scores from a population have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.[4][5] This standardization enables the assessment of relative performance or extremity without regard to the original units, such as comparing test results from exams with different means and variances. The concept of standardization traces its origins to the late 19th century, emerging from Karl Pearson's foundational contributions to the mathematical theory of evolution, including his introduction of the standard deviation in 1894. Although z-scores gain probabilistic interpretability under the assumption of an underlying normal distribution—for instance, linking values to percentiles in the standard normal curve—they remain useful beyond normality for gauging a score's relative standing within any distribution.[2][6][5]Properties

The standard score, or z-score, transforms a dataset to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. If the original distribution is normal, the result follows the standard normal distribution, which is symmetric and bell-shaped, facilitating comparison across different scales.[7] This standardization ensures that the distribution is centered at zero, with values indicating deviations from the mean in units of standard deviation, promoting uniformity in statistical analysis.[8] A key property of standard scores is their invariance under linear transformations of the original data. If the raw scores undergo an affine transformation—such as scaling by a positive constant and shifting by another constant—the resulting z-scores remain unchanged, preserving the relative distances between data points in terms of standard deviations.[9] This invariance arises because both the mean and standard deviation of the transformed data adjust proportionally, maintaining the z-score's scale-free nature.[7] For datasets approximating a normal distribution, standard scores adhere to the empirical rule, also known as the 68-95-99.7 rule. Approximately 68% of the data falls within ±1 standard deviation of the mean (z-scores between -1 and 1), 95% within ±2 standard deviations (z-scores between -2 and 2), and 99.7% within ±3 standard deviations (z-scores between -3 and 3).[10] This rule provides a quick heuristic for understanding data dispersion and probability coverage in normally distributed populations.[11] Standardization does not alter the shape of the distribution, including measures of skewness and kurtosis, which remain invariant under linear transformations. Skewness quantifies asymmetry, while kurtosis measures tail heaviness; these moments are unaffected by scaling or shifting, allowing z-scores to retain the original distribution's non-normality characteristics for assessment purposes.[12] Consequently, z-scores enable evaluation of normality through standardized skewness and kurtosis tests, where values near zero indicate symmetry and mesokurtosis akin to the normal distribution.[13] Despite these advantages, standard scores have notable limitations, particularly their sensitivity to outliers in small samples. Outliers can disproportionately inflate the mean and standard deviation, leading to distorted z-scores that misrepresent typical deviations.[14] Additionally, standardization does not induce normality; if the raw data is non-normal, the z-scores will inherit the same distributional irregularities, potentially invalidating assumptions in parametric tests.[15]Calculation and Standardization

Formula and Derivation

The standard score, or z-score, for a value from a population distributed as normal with mean and standard deviation is given by the formula This transformation standardizes the variable to express it in units of standard deviations from the mean.[16] To derive this formula and show that follows a standard normal distribution when , begin with the probability density function (PDF) of : Substitute , so , and apply the change-of-variable formula for the PDF, accounting for the Jacobian determinant : This is the PDF of the standard normal distribution.[16] The standardization yields a distribution with mean 0 and variance 1, as confirmed by the moments: the expected value , and the variance . These follow directly from the linearity of expectation and the definition of variance for the normal distribution. To verify unit variance via integration, compute . Using integration by parts or known Gaussian integrals, this equals 1, confirming the standard normal properties.[16] When population parameters and are unknown, sample estimates are used: the sample z-score is where is the sample mean and is the sample standard deviation, with degrees of freedom to provide an unbiased estimate of the population variance. This adjustment accounts for the loss of one degree of freedom when estimating the mean from the sample.[17][18] If (or for constant data), the z-score is undefined due to division by zero, as all values are identical and no variability exists for standardization. In non-normal distributions, the z-score formula remains applicable for descriptive purposes, but probabilistic interpretations assuming normality (e.g., via the standard normal table) do not hold, and the transformed values may not follow .Practical Computation Steps

To compute a standard score (z-score) for a dataset, follow these sequential steps. First, determine the mean of the data values, which serves as the central tendency; for a sample, this is , where is the number of observations and are the data points. Second, calculate the standard deviation to measure variability; for a sample, use , incorporating Bessel's correction (dividing by ) to provide an unbiased estimate of the population standard deviation. Third, for each individual score , subtract the mean and divide by the standard deviation: .[19][20] Consider a hypothetical dataset of exam scores: 70, 80, 90. The mean is . The sample standard deviation is (computed as ). The resulting z-scores are -1 for 70, 0 for 80, and 1 for 90, indicating the scores are one standard deviation below, at, and above the mean, respectively. This example illustrates how z-scores reposition raw values relative to the dataset's center and spread.[19] In practice, software tools streamline these computations, especially for larger datasets. In Microsoft Excel, the STANDARDIZE function computes z-scores directly with the syntax=STANDARDIZE(x, [mean](/page/Mean), standard_dev), where it normalizes a value based on provided mean and standard deviation parameters. In R, the scale() function from the base package centers and scales a numeric vector or matrix by default, subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation (with options to specify center and scale arguments); for a vector x, scale(x) yields z-scores. In Python, the scipy.stats.zscore function from SciPy computes z-scores for an array, using the syntax scipy.stats.zscore(a, ddof=0), where ddof=0 is the default (population standard deviation, dividing by n) and ddof=1 applies Bessel's correction for samples (dividing by n-1).[21][22][23]

For large datasets, leverage vectorized operations in these tools to avoid inefficient loops, enabling simultaneous computation across all elements for improved performance; for instance, R's scale() and SciPy's zscore inherently support this for arrays or matrices. When handling missing values, exclude them (listwise deletion) during mean and standard deviation calculations to prevent bias, as implemented by default in R's scale() (via na.rm=TRUE option) and SciPy's zscore (with nan_policy='omit').[24][22][23]

A common pitfall is misapplying the standard deviation type: using the population formula (dividing by ) instead of the sample formula (dividing by ) underestimates variability in finite samples, as the latter corrects for the bias introduced by estimating the mean from the data itself (Bessel's correction). Always verify whether the dataset represents the full population or a sample to select the appropriate formula.[20]

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} [X]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/44dd294aa33c0865f58e2b1bdaf44ebe911dbf93)

![{\displaystyle Z={X-\operatorname {E} [X] \over \sigma (X)}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4c8f3b9ca897926a8d0e28707f1400b9396986da)

![{\displaystyle Z={\frac {{\bar {X}}-\operatorname {E} [{\bar {X}}]}{\sigma (X)/{\sqrt {n}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2acf468c72121de0afb89521b2b709c042730963)