Bob

Have a question related to this hub?

Alice

Got something to say related to this hub?

Share it here.

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ratification statuses in signatory states: process completed process not complete process stopped | |||||||||||

| Type | Military pact | ||||||||||

| Context | European integration | ||||||||||

| Drafted | 24 October 1950 | ||||||||||

| Signed | 27 May 1952 | ||||||||||

| Location | Paris | ||||||||||

| Condition | Ratification by all founding states | ||||||||||

| Expiry | 50 years after entry into effect | ||||||||||

| Parties | 6

| ||||||||||

| Ratifiers | 4 / 6

| ||||||||||

| Depositary | Government of France | ||||||||||

| Full text | |||||||||||

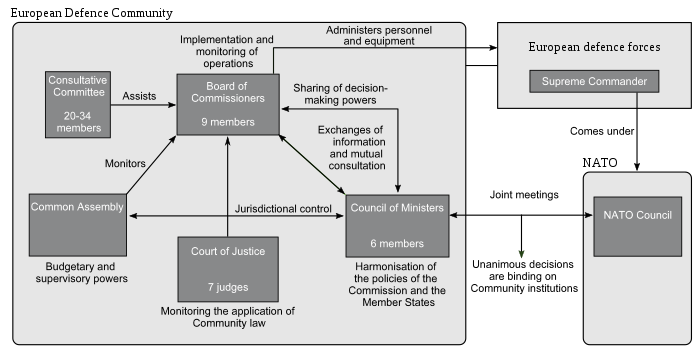

The Treaty establishing the European Defence Community (EDC), also known as the Treaty of Paris,[1] is a treaty of European integration, which upon entry into force would create a European defence force, with shared budget and joint procurement. This force would operate as an autonomous European pillar within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

The treaty was signed on 27 May 1952 by Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, France, Italy, and West Germany. Article 129 of the treaty allows for additional countries to join the community.

By 1954, four out of the six signatories had ratified the treaty. Ratification by France and Italy was not completed, after the French National Assembly voted for indefinite postponement of the process in 1954.[2] The treaty was never formally annulled and ratification remains technically open for completion.[3] Recent geopolitical developments—including the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the re-election of U.S. President Donald Trump in 2024—have renewed interest in the treaty. On 3 April 2025, a bill to ratify the EDC was introduced in both chambers of the Italian Parliament.[4][5][2]

The EDC would entail a unified defence, divided into national components, funded by a common budget, common arms, centralized military procurement, and institutions.

Establishes the intent to strengthen peace and unity in Europe, ensure security, and lay the groundwork for eventual political federation.

Articles 1–7: Legal foundation, aims, principles (e.g., peaceful purpose, equal treatment, NATO cooperation), juridical personality.

Articles 8–12: Establishment of integrated armed forces; restrictions and exceptions for national forces (e.g., police, UN missions, royal guards).

Articles 13–20: Overview of the four institutions: Council of Ministers, Commissariat, Assembly, Court of Justice. Defines legal powers and responsibilities.

Articles 21–30: Composition, voting rules, responsibilities in policy, defense, finance, and inter-institutional cooperation.

Articles 31–40: Executive arm of the Community, responsible for administration, budget execution, operational command, and reporting.

Articles 41–48: Legislative and supervisory body; representatives from member states; powers include approval of budget and motions of censure.

Articles 49–60: Judicial authority to interpret and ensure uniform application of the treaty; jurisdiction over institutions and member states.

Articles 61–71: Details the military command structure, staff organization, training standards, and integration procedures.

Articles 72–84: Establishes Community budget, financial contributions, auditing, and control of expenditures.

Articles 85–90: Obligations regarding treaty compliance, cooperation, enforcement of Community decisions, and prohibition of conflicting agreements.

Articles 91–95: Outlines relations with NATO, the UN, and other international organizations to ensure coordination and consistency.

Articles 96–104: Legal status, discipline, and rights of military and civilian personnel under the Community's jurisdiction.

Articles 105–113: Rules on armaments, shared resources, procurement procedures, and allocation of infrastructure.

Articles 114–120: Transitional arrangements for integrating national forces and institutions; special protocols for initial phases.

Articles 121–132:

The table below summarizes the status of ratification of the treaty by the signatory states. By 1954 4 states had completed ratification, with the process in the remaining 2 states on hold.

| Signatory | Institution | Date | AB | Deposited | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senate | 12 March 1954 | 125 | 40 | 2 | ? | [6] | |

| Chamber of Representatives | 26 November 1953 | 148 | 49 | 3 | ? | [7] | |

| National Assembly | |||||||

| Council of the Republic | |||||||

| Federal Diet | 19 March 1953 | 224 | 165 | ? | ? | [8] | |

| Federal Council | 15 May 1953 | ? | ? | ? | ? | [8] | |

| Senate | ? | [4] | |||||

| Chamber of Deputies | ? | [9] | |||||

| Chamber of Deputies | 7 April 1954 | 47 | 3 | 1 | ? | [10] | |

| House of Representatives | 23 July 1953 | 75 | 11 | 0 | ? | [11] | |

| Senate | 20 January 1954 | 36 | 4 | 10 | ? | [12] |

Recent geopolitical developments—including the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the re-election of U.S. President Donald Trump in 2024—have renewed interest in the treaty. A 2024 article by Professor Federico Fabbrini at Dublin City University,[3] as well as a 2025 study led by former French defence minister Sylvie Goulard,[2] have found that it is still legally feasible for Italy and France to ratify the treaty, thereby bringing it into force. This suggests that the ratification process that halted in 1954 may proceed.

On 30 August 1954, the French National Assembly voted 264 against, 319 in favour and 31 abstentions on a motion for indefinite postponement of ratification.[2]

By the time of the vote, concerns about a future conflict faded with the death of Joseph Stalin and the end of the Korean War. Concomitant to these fears were a severe disjuncture between the original Pleven Plan of 1950 and the one defeated in 1954. Divergences included military integration at the division rather than battalion level and a change in the command structure putting NATO's Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) in charge of EDC operational capabilities. The reasons that led to the failed ratification of the Treaty were twofold, concerning major changes in the international scene, as well as domestic problems of the French Fourth Republic.[13] There were Gaullist fears that the EDC threatened France's national sovereignty, constitutional concerns about the indivisibility of the French Republic, and fears about West Germany's remilitarization. French Communists opposed a plan tying France to the capitalist United States and setting it in opposition to the Communist bloc. Other legislators worried about the absence of the United Kingdom.

The Prime Minister, Pierre Mendès-France, tried to placate the treaty's detractors by attempting to ratify additional protocols with the other signatory states. These included the sole integration of covering forces, or in other words, those deployed within West Germany, as well as the implementation of greater national autonomy in regard to budgetary and other administrative questions. Despite the central role for France, the EDC plan collapsed when it failed to obtain ratification in the French Parliament.

The original ratification process in Italy was halted after the French National Assembly voted for indefinite postponement.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the re-election of US President Trump in 2024, the treaty has regained interest.[5]

On 3 April 3 2025, deputy Mauro Del Barba (Italia Viva – Centro – Renew Europe) tabled a bill to ratify the treaty in both chambers of Parliament. As of now, the bill is still under review and has not yet been assigned to a specific committee for further consideration.[4][9][14][15]

| History of the European Union |

|---|

|

|

|

During the late 1940s, the divisions created by the Cold War were becoming evident. The United States looked with suspicion at the growing power of the USSR and European states felt vulnerable, fearing a possible Soviet occupation. In this climate of mistrust and suspicion, the United States considered the rearmament of West Germany as a possible solution to enhance the security of Europe and of the whole Western bloc.[16]

In August 1950, Winston Churchill proposed the creation of a common European army, including German soldiers, in front of the Council of Europe:

“We should make a gesture of practical and constructive guidance by declaring ourselves in favour of the immediate creation of a European Army under a unified command, and in which we should all bear a worthy and honourable part.”

— Winston Churchill, speech at the Council of Europe 1950[17]

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe subsequently adopted the resolution put forward by the United Kingdom and officially endorsed the idea:

“The Assembly, in order to express its devotion to the maintenance of peace and its resolve to sustain the action of the Security Council of the United Nations in defence of peaceful peoples against aggression, calls for the immediate creation of a unified European Army subject to proper European democratic control and acting in full co-operation with the United States and Canada.”

— Resolution of the Council of Europe 1950[17]

In September 1950, Dean Acheson, under a cable submitted by High Commissioner John J. McCloy, proposed a new plan to the European states; the American plan, called package, sought to enhance NATO's defense structure, creating 12 West German divisions. However, after the destruction that Germany had caused during World War II, European countries, in particular France, were not ready to see the reconstruction of the German military.[18] Finding themselves in the midst of the two superpowers, they looked at this situation as a possibility to enhance the process of integrating Europe, trying to obviate the loss of military influence caused by the new bipolar order and thus supported a common army.[19]

The treaty was initiated by the Pleven plan, proposed in 1950 by then French Prime Minister René Pleven in response to the American call for the rearmament of West Germany. The formation of a pan-European defence architecture, as an alternative to West Germany's proposed accession to NATO, was meant to harness the German military potential in case of conflict with the Soviet bloc. Just as the Schuman Plan was designed to end the risk of Germany having the economic power on its own to make war again, the Pleven Plan and EDC were meant to prevent the military possibility of Germany's making war again.

On 24 October 1950, France's Prime Minister René Pleven proposed a new plan, which took his name although it was drafted mainly by Jean Monnet, that aimed to create a supranational European army. With this project, France tried to satisfy America's demands, avoiding, at the same time, the creation of German divisions, and thus the rearmament of Germany.[20][21]

“Confident as it is that Europe’s destiny lies in peace and convinced that all the peoples of Europe need a sense of collective security, the French Government proposes […] the creation, for the purposes of common defence, of a European army tied to the political institutions of a united Europe.”

— René Pleven, speech at the French Parliament 1950[22]

The EDC was to include West Germany, France, Italy, and the Benelux countries. The United States would be excluded. It was a competitor to NATO (in which the US played the dominant role), with France playing the dominant role. Just as the Schuman Plan was designed to end the risk of Germany having the economic power to make war again, the Pleven Plan and EDC were meant to prevent the same possibility. Britain approved of the plan in principle, but agreed to join only if the supranational element was decreased.[23]

According to the Pleven Plan, the European Army was supposed to be composed of military units from the member states, and directed by a council of the member states’ ministers. Although with some doubts and hesitation, the United States and the six members of the ECSC approved the Pleven Plan in principle.

The initial approval of the Pleven Plan led the way to the Paris Conference, launched in February 1951, where it was negotiated the structure of the supranational army.

France feared the loss of national sovereignty in security and defense, and thus a truly supranational European Army could not be tolerated by Paris.[24] However, because of the strong American interest in a West German army, a draft agreement for a modified Pleven Plan, renamed the European Defense Community (EDC), was ready in May 1952, with French support.

On 27 May 1952 the foreign ministers of the six 'inner' countries of European integration signed the treaty:[25]

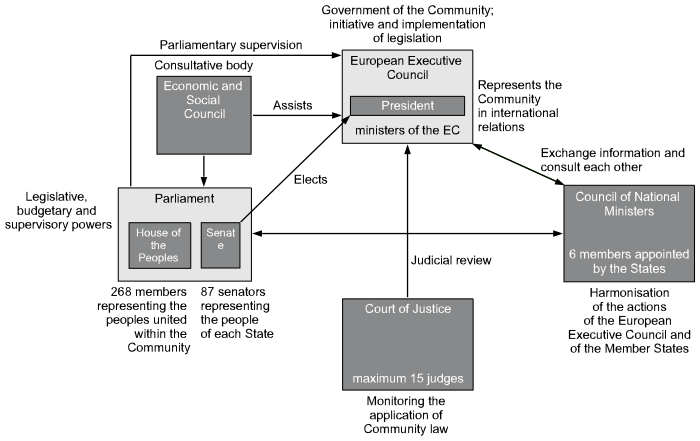

A European Political Community (EPC) was proposed in 1952 as a combination of the existing European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the proposed European Defence Community (EDC). A draft EPC treaty, as drawn up by the ECSC assembly (now the European Parliament), would have seen a directly elected assembly ("the Peoples’ Chamber"), a senate appointed by national parliaments and a supranational executive accountable to the parliament.

In 1953 and 1954, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany ratified the treaty.

Following the French National Assembly's vote to indefinitely postpone ratification in 1954, Italian ratification was also put on hold.

This resulted in the

Since the end of World War II, most sovereign European countries have entered into treaties and thereby co-operated and harmonised policies (or pooled sovereignty) in an increasing number of areas, in the European integration project or the construction of Europe (French: la construction européenne). The following timeline outlines the legal inception of the European Union (EU)—the principal framework for this unification. The EU inherited many of its present organizations, institutions, and responsibilities from the European Communities (EC), which were founded in the 1950s in the spirit of the Schuman Declaration.

| Legend: S: signing F: entry into force T: termination E: expiry de facto supersession Rel. w/ EC/EU framework: de facto inside outside |

[Cont.] | |||||||||||||||||

| (Pillar I) | ||||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or EURATOM) | [Cont.] | |||||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Schengen Rules | European Community (EC) | |||||||||||||||||

| TREVI | Justice and Home Affairs (JHA, pillar III) | |||||||||||||||||

| [Cont.] | Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC, pillar III) | |||||||||||||||||

Anglo-French alliance |

[Defence arm handed to NATO] | European Political Co-operation (EPC) | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP, pillar II) | |||||||||||||||

| [Tasks defined following the WEU's 1984 reactivation handed to the EU] | ||||||||||||||||||

| [Social, cultural tasks handed to CoE] | [Cont.] | |||||||||||||||||

Entente Cordiale

S: 8 April 1904 |

Davignon report

S: 27 October 1970 |

European Council conclusions

S: 2 December 1975 |

||||||||||||||||