Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

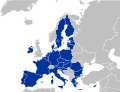

Member state of the European Union

View on Wikipedia

| Member state of the European Union | |

|---|---|

| |

| Category | Member state |

| Location | European Union |

| Created |

|

| Number | 27 (as of 2025) |

| Possible types |

|

| Populations | Smallest: Malta, 542,051 Largest: Germany, 84,358,845[1] |

| Areas | Smallest: Malta, 316 km2 (122 sq mi) Largest: France, 638,475 km2 (246,517 sq mi)[2] |

| Government |

|

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union of 27 member states that are party to the EU's founding treaties, and thereby subject to the privileges and obligations of membership. They have agreed by the treaties to share their own sovereignty through the institutions of the European Union in certain aspects of government. State governments must agree unanimously in the Council for the union to adopt some policies; for others, collective decisions are made by qualified majority voting. These obligations and sharing of sovereignty within the EU make it unique among international organisations, as it has established its own legal order which by the provisions of the founding treaties is both legally binding and supreme on all the member states (after a landmark ruling of the ECJ in 1964). A founding principle of the union is subsidiarity, meaning that decisions are taken collectively if and only if they cannot realistically be taken individually.

Each member country appoints to the European Commission a European commissioner. The commissioners do not represent their member state, but instead work collectively in the interests of all the member states within the EU.

In the 1950s, six core states founded the EU's predecessor European Communities (Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany). The remaining states have acceded in subsequent enlargements. To accede, a state must fulfil the economic and political requirements known as the Copenhagen criteria, which require a candidate to have a democratic government and free-market economy together with the corresponding freedoms and institutions, and respect for the rule of law. Enlargement of the Union is also contingent upon the consent of all existing members and the candidate's adoption of the existing body of EU law, known as the acquis communautaire.

The United Kingdom, which had acceded to the EU's predecessor in 1973, ceased to be an EU member state on 31 January 2020, in a political process known as Brexit. No other member state has withdrawn from the EU and none has been suspended, although some dependent territories or semi-autonomous areas have left.

List

[edit]| Country | ISO | Accession | Population[3] | Area (km2) |

Largest city |

GDP (US$ M) |

GDP (PPP) per cap.[4][5] |

Currency | Gini[6] | HDI[7] | MEPs | Official languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 1 January 1995 | 8,926,000 | 83,855 | Vienna | 535,804 | 73,050 | euro | 29.1 | 0.930 | 20 | German | |

| BE | Founder | 11,566,041 | 30,528 | Brussels | 662,183 | 73,221 | euro | 33.0 | 0.951 | 22 | Dutch French German | |

| BG | 1 January 2007 | 6,916,548 | 110,994 | Sofia | 66,250 | 39,185 | lev | 29.2 | 0.845 | 17 | Bulgarian | |

| HR | 1 July 2013 | 4,036,355 | 56,594 | Zagreb | 89,665 | 48,811 | euro | 29 | 0.878 | 12 | Croatian | |

| CY | 1 May 2004 | 896,000 | 9,251 | Nicosia | 23,380 | 59,858 | euro | 31.2 | 0.913 | 6 | Greek Turkish[b] | |

| CZ | 1 May 2004 | 10,574,153 | 78,866 | Prague | 246,953 | 56,686 | koruna | 25.8 | 0.915 | 21 | Czech[c] | |

| DK | 1 January 1973 | 5,833,883 | 43,075 | Copenhagen | 347,176 | 83,454 | krone | 24.7 | 0.962 | 15 | Danish | |

| EE | 1 May 2004 | 1,330,068 | 45,227 | Tallinn | 43,044 | 48,008 | euro | 36.0 | 0.905 | 7 | Estonian | |

| FI | 1 January 1995 | 5,527,493 | 338,424 | Helsinki | 306,083 | 64,657 | euro | 26.9 | 0.948 | 15 | Finnish Swedish | |

| FR | Founder | 67,439,614 | 632,786[8][f] | Paris | 2,707,074 | 65,940 | euro | 32.7 | 0.920 | 81 | French | |

| DE | Founder[g] | 83,120,520 | 357,386 | Berlin | 4,710,032 | 70,930 | euro | 31.9 | 0.959 | 96 | German | |

| GR | 1 January 1981 | 10,682,547 | 131,990 | Athens | 214,012 | 42,066 | euro | 34.3 | 0.908 | 21 | Greek | |

| HU | 1 May 2004 | 9,730,772 | 93,030 | Budapest | 170,407 | 46,807 | forint | 30.0 | 0.870 | 21 | Hungarian | |

| IE | 1 January 1973 | 5,006,324 | 70,273 | Dublin | 384,940 | 127,750 | euro | 34.3 | 0.949 | 14 | English Irish | |

| IT | Founder | 58,968,501 | 301,338 | Rome | 1,988,636 | 60,993 | euro | 36.0 | 0.915 | 76 | Italian | |

| LV | 1 May 2004 | 1,862,700 | 64,589 | Riga | 35,045 | 43,527 | euro | 35.7 | 0.889 | 9 | Latvian | |

| LT | 1 May 2004 | 2,795,680 | 65,200 | Vilnius | 53,641 | 53,624 | euro | 35.8 | 0.895 | 11 | Lithuanian | |

| LU | Founder | 633,347 | 2,586.4 | Luxembourg | 69,453 | 151,146 | euro | 30.8 | 0.922 | 6 | Luxembourgish[h] French German | |

| MT | 1 May 2004 | 516,100 | 316 | Valletta | 14,859 | 72,942 | euro | 25.8 | 0.924 | 6 | Maltese English | |

| NL | Founder | 17,614,840 | 41,543 | Amsterdam | 902,355 | 81,495 | euro | 30.9 | 0.955 | 31 | Dutch | |

| PL | 1 May 2004 | 37,840,001 | 312,685 | Warsaw | 565,854 | 51,629 | złoty | 34.9 | 0.906 | 56 | Polish | |

| PT | 1 January 1986 | 10,298,252[9] | 92,212[10] | Lisbon | 236,408 | 49,237 | euro | 32.1[11] | 0.890 | 21 | Portuguese[k] | |

| RO | 1 January 2007 | 19,186,201 | 238,391 | Bucharest | 243,698 | 47,204 | leu | 31.5 | 0.845 | 33 | Romanian | |

| SK | 1 May 2004 | 5,422,194 | 49,035 | Bratislava | 106,552 | 45,632 | euro | 25.8 | 0.880 | 15 | Slovak | |

| SI | 1 May 2004 | 2,108,977 | 20,273 | Ljubljana | 54,154 | 55,684 | euro | 31.2 | 0.931 | 9 | Slovene | |

| ES | 1 January 1986 | 48,946,035 | 504,030 | Madrid | 1,647,114 | 55,089 | euro | 32.0 | 0.918 | 61 | Spanish[m] | |

| SE | 1 January 1995 | 10,370,000 | 449,964 | Stockholm | 528,929 | 71,731 | krona | 25.0 | 0.959 | 21 | Swedish |

Notes

- ^ De facto (though not de jure) excludes the disputed territory of Turkish Cyprus and the U.N. buffer zone. See: Cyprus dispute.

- ^ The Turkish language is not an official language of the European Union.

- ^ Officially recognised minority languages:

- ^ Excludes the autonomous regions of Greenland, which left the then-EEC in 1985, and the Faroe Islands.

- ^ Includes Åland, an autonomous region of Finland.

- ^ a b Includes the 101 departments (Metropolitan France + all Overseas Departments: Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Martinique, Mayotte and La Réunion) and the overseas collectivity of Saint Martin, which are part of the European Union. Excludes the other overseas collectivities and French Austral and Antarctic Lands which are not part of the European Union.

- ^ On 3 October 1990, the territory of the former German Democratic Republic acceded to the Federal Republic of Germany to form present-day Germany, automatically becoming part of the EU.

- ^ While Luxembourgish is the national language, it is not an official language of the European Union.

- ^ Excludes the three special municipalities of the Netherlands (Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba). Also excludes the three other constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten).

- ^ Includes the autonomous regions of the Azores and Madeira.

- ^ Mirandese is an officially recognized minority language within Portugal, awarded an official right-of-use. It is not an official language of the European Union.

- ^ Includes the autonomous community of the Canary Islands; the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla; and the territories comprising the plazas de soberanía.

- ^ Basque, Catalan, and Galician are co-official languages with Spanish in their respective territories, allowing their use in EU institutions under limited circumstances.[12]

Former member state

[edit]| Country | ISO | Accession | Withdrawal | Population[3] | Area (km2) | Largest city | GDP (US$ M) |

GDP (PPP) per cap.[4][5] |

Currency | Gini[6] | HDI[7] | Official languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB | 1 January 1973 | 31 January 2020 | 67,791,400 | 242,495 | London | 3,158,938 | 62,574 | sterling | 36.6 | 0.946 | English |

Outermost regions

[edit]There are a number of overseas member state territories which are legally part of the EU, but have certain exemptions based on their remoteness; see Overseas Countries and Territories Association. These "outermost regions" have partial application of EU law and in some cases are outside of Schengen or the EU VAT area—however they are legally within the EU.[13] They all use the euro as their currency.

| Territory | Member State | Location | Area km2 |

Population | Per capita GDP (EU=100) |

EU VAT area | Schengen Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azores | Portugal | Atlantic Ocean | 2,333 | 236,440 | 66.7 | Yes | Yes |

| Canary Islands | Spain | Atlantic Ocean | 7,447 | 2,202,048 | 93.7 | No | Yes |

| French Guiana | France | South America | 84,000 | 295,385 | 50.5 | No | No |

| Guadeloupe | France | Caribbean | 1,710 | 378,561 | 50.5 | No | No |

| Madeira | Portugal | Atlantic Ocean | 795 | 250,769 | 94.9 | Yes | Yes |

| Saint-Martin | France | Caribbean | 52 | 31,477 | 61.9 | No | No |

| Martinique | France | Caribbean | 1,080 | 349,925 | 75.6 | No | No |

| Mayotte[14] | France | Indian Ocean | 374 | 320,901 | No | No | |

| Réunion | France | Indian Ocean | 2,512 | 885,700 | 61.6 | No | No |

Abbreviations

[edit]Abbreviations have been used as a shorthand way of grouping countries by their date of accession.

- EU15 includes the fifteen countries in the European Union from 1 January 1995 to 30 April 2004. The EU15 comprised Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom.[15] Eurostat still uses this expression.

- EU19 includes the countries in the EU15 as well as the Central European member countries of the OECD: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovak Republic.[16]

- EU11 is used to refer to the Central, Southeastern Europe and Baltic European member states that joined in 2004, 2007 and 2013: in 2004 the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia; in 2007 Bulgaria, Romania; and in 2013 Croatia.[17][18]

- EU27 means all the member states. It was originally used in this sense from 2007 until Croatia's accession in 2013, and during the Brexit negotiations from 2017 until the United Kingdom's withdrawal on 31 January 2020 it came to mean all members except the UK.

- EU28 meant all the member states from the accession of Croatia in 2013 to the withdrawal of the United Kingdom in 2020.

Additionally, other abbreviations have been used to refer to countries which had limited access to the EU labour market.[19]

- A8 is eight of the ten countries that joined the EU in 2004, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia.

- A2 is the countries that joined the EU in 2007, Bulgaria and Romania.

Changes in membership

[edit]Enlargement

[edit]

According to the Copenhagen criteria, membership of the European Union is open to any European country that is a stable, free-market liberal democracy that respects the rule of law and human rights. Furthermore, it has to be willing to accept all the obligations of membership, such as adopting all previously agreed law (the 170,000 pages of acquis communautaire) and switching to the euro.[20] For a state to join the European Union, the prior approval of all current member states is required. In addition to enlargement by adding new countries, the EU can also expand by having territories of member states, which are outside the EU, integrate more closely (for example in respect to the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles) or by a territory of a member state which had previously seceded and then rejoined (see withdrawal below).

Suspension

[edit]There is no provision to expel a member state, but TEU Article 7 provides for the suspension of certain rights. Introduced in the Treaty of Amsterdam, Article 7 outlines that if a member persistently breaches the EU's founding principles (liberty, democracy, human rights and so forth, outlined in TEU Article 2) then the European Council can vote to suspend any rights of membership, such as voting and representation. Identifying the breach requires unanimity (excluding the state concerned), but sanctions require only a qualified majority.[21]

The state in question would still be bound by the obligations treaties and the Council acting by majority may alter or lift such sanctions. The Treaty of Nice included a preventive mechanism whereby the council, acting by majority, may identify a potential breach and make recommendations to the state to rectify it before action is taken against it as outlined above.[21] However, the treaties do not provide any mechanism to expel a member state outright.[22]

Withdrawal

[edit]Prior to the Lisbon Treaty, there was no provision or procedure within any of the Treaties of the European Union for a member state to withdraw from the European Union or its predecessor organisations. The Lisbon Treaty changed this and included the first provision and procedure of a member state to leave the bloc. The procedure for a state to leave is outlined in TEU Article 50 which also makes clear that "Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements". Although it calls for a negotiated withdrawal between the seceding state and the rest of the EU, if no agreement is reached two years after the seceding state notifying of its intention to leave, it would cease to be subject to the treaties anyway (thus ensuring a right to unilateral withdrawal).[22] There is no formal limit to how much time a member state can take between adopting a policy of withdrawal, and actually triggering Article 50.[citation needed]

In a referendum in June 2016, the United Kingdom voted to withdraw from the EU. The UK government triggered Article 50 on 29 March 2017.[23] After an extended period of negotiation and internal political debate the UK eventually withdrew from the EU on 31 January 2020.[24][25]

Prior to 2016, no member state had voted to withdraw. However, French Algeria, Greenland and Saint-Barthélemy did cease being part of the EU (or its predecessor) in 1962, 1985, and 2012, respectively, due to status changes. The situation of Greenland being outside the EU while still subject to an EU member state had been discussed as a template for the pro-EU regions of the UK remaining within the EU or its single market.[26]

Beyond the formal withdrawal of a member state, there are a number of independence movements such as Catalonia or Flanders which could result in a similar situation to Greenland. Were a territory of a member state to secede but wish to remain in the EU, some scholars claim it would need to reapply to join as if it were a new country applying from scratch.[27] However, other studies claim internal enlargement is legally viable if, in case of a member state dissolution or secession, the resulting states are all considered successor states.[28] There is also a European Citizens' Initiative that aims at guaranteeing the continuity of rights and obligations of the European citizens belonging to a new state arising from the democratic secession of a European Union member state.[29]

Representation

[edit]

Each state has representation in the institutions of the European Union. Full membership gives the government of a member state a seat in the Council of the European Union and European Council. When decisions are not being taken by consensus, qualified majority voting (which requires majorities both of the number of states and of the population they represent, but a sufficient blocking minority can veto the proposal). The Presidency of the Council of the European Union rotates among each of the member states, allowing each state six months to help direct the agenda of the EU.[30][31]

Similarly, each state is assigned seats in Parliament according to their population (smaller countries receiving more seats per inhabitant than the larger ones). The members of the European Parliament have been elected by universal suffrage since 1979 (before that, they were seconded from national parliaments).[32][33]

The national governments appoint one member each to the European Commission, the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Auditors. Prospective Commissioners must be confirmed both by the President of the Commission and by the European Parliament; prospective justices must be confirmed by the existing members. Historically, larger member states were granted an extra Commissioner. However, as the body grew, this right has been removed and each state is represented equally. The six largest states are also granted an Advocates General in the Court of Justice. Finally, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank includes the governors of the national central banks (who may or may not be government appointed) of each euro area country.[34]

The larger states traditionally carry more weight in negotiations, however smaller states can be effective impartial mediators and citizens of smaller states are often appointed to sensitive top posts to avoid competition between the larger states. This, together with the disproportionate representation of the smaller states in terms of votes and seats in parliament, gives the smaller EU states a greater power of influence than is normally attributed to a state of their size. However most negotiations are still dominated by the larger states. This has traditionally been largely through the "Franco-German motor" but Franco-German influence has diminished slightly following the influx of new members in 2004 (see G6).[35]

Sovereignty

[edit]

- In accordance with Article 5, competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the member states.

- The Union shall respect the equality of member states before the Treaties as well as their national identities, inherent in their fundamental structures, political and constitutional, inclusive of regional and local self-government. It shall respect their essential State functions, including ensuring the territorial integrity of the State, maintaining law and order and safeguarding national security. In particular, national security remains the sole responsibility of each member state.

- Pursuant to the principle of sincere cooperation, the Union and the member states shall, in full mutual respect, assist each other in carrying out tasks which flow from the Treaties. The member states shall take any appropriate measure, general or particular, to ensure fulfilment of the obligations arising out of the Treaties or resulting from the acts of the institutions of the Union. The member states shall facilitate the achievement of the Union's tasks and refrain from any measure which could jeopardise the attainment of the Union's objectives.

While the member states are sovereign, the union partially follows a supranational system for those functions agreed by treaty to be shared. ("Competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the member states"). Previously limited to European Community matters, the practice, known as the 'community method', is currently used in many areas of policy. Combined sovereignty is delegated by each member to the institutions in return for representation within those institutions. This practice is often referred to as 'pooling of sovereignty'. Those institutions are then empowered to make laws and execute them at a European level.

In contrast to some international organisations, the EU's style of integration as a union of states does not "emphasise sovereignty or the separation of domestic and foreign affairs [and it] has become a highly developed system for mutual interference in each other's domestic affairs, right down to beer and sausages.".[36] However, on defence and foreign policy issues (and, pre-Lisbon Treaty, police and judicial matters) less sovereignty is transferred, with issues being dealt with by unanimity and co-operation. Very early on in the history of the EU, the unique state of its establishment and pooling of sovereignty was emphasised by the Court of Justice:[37]

By creating a Community of unlimited duration, having its own institutions, its own personality, its own legal capacity and capacity of representation on the international plane and, more particularly, real powers stemming from a limitation of sovereignty or a transfer of powers from the States to Community, the Member States have limited their sovereign rights and have thus created a body of law which binds both their nationals and themselves...The transfer by the States from their domestic legal system to the Community legal system of the rights and obligations arising under the Treaty carries with it a permanent limitation of their sovereign rights.

— European Court of Justice 1964, in reference to case of Costa v ENEL[38]

The question of whether Union law is superior to State law is subject to some debate. The treaties do not give a judgement on the matter but court judgements have established EU's law superiority over national law and it is affirmed in a declaration attached to the Treaty of Lisbon (the proposed European Constitution would have fully enshrined this). The legal systems of some states also explicitly accept the Court of Justice's interpretation, such as France and Italy, however in Poland it does not override the state's constitution, which it does in Germany.[39][40] The exact areas where the member states have given legislative competence to the Union are as follows. Every area not mentioned remains with member states.[41]

Competences

[edit]In EU terminology, the term 'competence' means 'authority or responsibility to act'. The table below shows which aspects of governance are exclusively for collective action (through the commission) and which are shared to a greater or lesser extent. If an aspect is not listed in the table below, then it remains the exclusive competence of the member state. Perhaps the best known example is taxation, which remains a matter of state sovereignty.

|

|

| |||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

Conditional mutual support

[edit]As a result of the European sovereign debt crisis, some eurozone states were given a bailout from their fellow members via the European Financial Stability Facility and European Financial Stability Mechanism (replaced by the European Stability Mechanism from 2013), but this came with conditions. As a result of the Greek government-debt crisis, Greece accepted a large austerity plan including privatisations and a sell off of state assets in exchange for their bailout. To ensure that Greece complied with the conditions set by the European troika (ECB, IMF, Commission), a 'large-scale technical assistance' from the European Commission and other member states was deployed to Greek government ministries. Some, including the President of the Euro Group Jean-Claude Juncker, stated that "the sovereignty of Greece will be massively limited."[43][44][45] The situation of the bailed out countries (Greece, Portugal and Ireland) has been described as being a ward[46][47] or protectorate[45][48][49] of the EU with some such as the Netherlands calling for a formalisation of the situation.[50]

Multi-speed integration

[edit]EU integration is not always symmetrical, with some states proceeding with integration ahead of hold-outs. There are several different forms of closer integration both within and outside the EU's normal framework. One mechanism is enhanced cooperation where nine or more states can use EU structures to progress in a field that not all states are willing to partake in.[51] Some states have gained an opt-out in the founding treaties from participating in certain policy areas.[52][53]

Political systems

[edit]

The admission of a new state the Union is limited to liberal democracies and Freedom House ranks all EU states as being totally free electoral democracies.[54] All but 4 are ranked at the top 1.0 rating.[55] However, the exact political system of a state is not limited, with each state having its own system based on its historical evolution.

More than half of member states—16 out of 27—are parliamentary republics, while six states are constitutional monarchies, meaning they have a monarch although political powers are exercised by elected politicians. Most republics and all the monarchies operate a parliamentary system whereby the head of state (president or monarch) has a largely ceremonial role with reserve powers. That means most power is in the hands of what is called in most of those countries the prime minister, who is accountable to the national parliament. Of the remaining republics, four[clarification needed] operate a semi-presidential system, where competences are shared between the president and prime minister, while one republic operates a presidential system, where the president is head of both state and government.

Parliamentary structure in member states varies: there are 15 unicameral national parliaments and 12 bicameral parliaments. The prime minister and government are usually directly accountable to the directly elected lower house and require its support to stay in office—the exception being Cyprus with its presidential system. Upper houses are composed differently in different member states: it can be directly elected like the Polish senate; indirectly elected, for example, by regional legislatures like the Federal Council of Austria; or unelected, but representing certain interest groups like the National Council of Slovenia. All elections in member states use some form of proportional representation. The most common type of proportional representation is the party-list system.[citation needed]

There are also differences in the level of self-governance for the sub-regions of a member state. Most states, especially the smaller ones, are unitary states; meaning all major political power is concentrated at the national level. 9 states allocate power to more local levels of government. Austria, Belgium and Germany are full federations, meaning their regions have constitutional autonomies. Denmark, Finland, France and the Netherlands are federacies, meaning some regions have autonomy but most do not. Spain and Italy have systems of devolution where regions have autonomy, but the national government retains the legal right to revoke it.[56]

States such as France have a number of overseas territories, retained from their former empires.

See also

[edit]- Currencies of the European Union

- Economy of the European Union

- Enlargement of the European Union (1973–2013)

- European Economic Area (integration with the EFTA States)

- History of the European Union

- Microstates and the European Union

- Potential enlargement of the European Union

- Special member state territories and the European Union

- United Kingdom membership of the European Union

- Withdrawal from the European Union

- Member states of NATO

Notes

[edit]- ^ The first states first formed the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952 and then created the parallel European Economic Community in 1958. Although the latter was later, it is more often considered the immediate predecessor to the EU. The former has always shared the same membership and has since been absorbed by the EU, which was formally established in 1993.

References

[edit]- ^ "Population change - Demographic balance and crude rates at national level". Eurostat. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Area by NUTS 3 region". Eurostat. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ a b Council Decision (EU, Euratom) 2021/2320 of 22 December 2021 amending the Council's Rules of Procedure (Decision 2021/2320). Council of the European Union. 22 December 2021.

- ^ a b at purchasing power parity, per capita, in international dollars (rounded)

- ^ a b "IMF". www.imf.org. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ a b "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data.

- ^ a b "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ "Comparateur de territoires − Comparez les territoires de votre choix - Résultats pour les communes, départements, régions, intercommunalités... | Insee". www.insee.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "Statistics Portugal - Web Portal". www.ine.pt. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "Portugal tem 92.212 quilómetros quadrados, por enquanto... - Sociedade - PUBLICO.PT". 5 October 2012. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Índice de Gini (percentagem)". www.pordata.pt. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "Regional and minority languages in the European Union" (PDF) (PDF). European Parliament Members' Research Service. September 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Regional policy & outermost regions Archived 16 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, European Commission

- ^ "Council Directive 2013/61/EU of December 2013" (PDF). 17 December 2013. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms - EU15 Definition". stats.oecd.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms - EU21 Definition". stats.oecd.org. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Vértesy, László (2018). "Macroeconomic Legal Trends in the EU11 Countries" (PDF). Public Governance, Administration and Finances Law Review. 3. No. 1. 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Loichinger, Elke; Madzarevic-Sujster, Sanja; Vincelette, Gallina A.; Laco, Matija; Korczyc, Ewa (1 June 2013). "EU11 regular economic report". pp. 1–92. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Who are the "A8 countries"?". 24 April 2005. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Accession criteria". Europa. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- ^ a b Suspension clause Archived 22 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Europa glossary. Retrieved 22 December 2017

- ^ a b Athanassiou, Phoebus (December 2009) Withdrawal and Expulsion from the EU and EMU, Some Reflections Archived 20 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), European Central Bank. Retrieved 8 September 2011

- ^ Elgot, Jessica (2 October 2016). "Theresa May to trigger article 50 by end of March 2017". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Brexit: MPS back Boris Johnson's plan to leave EU on 31 January". BBC News. 20 December 2019. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Brexit: European Parliament overwhelmingly backs terms of UK's exit". BBC News. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Could a 'reverse Greenland' arrangement keep Scotland and Northern Ireland in the EU? Archived 22 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, London School of Economics 7 July 2016

- ^ Happold, Matthew (1999) Scotland Europa: independence in Europe? Archived 22 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Centre for European Reform. Retrieved 14 June 2010 (PDF)

- ^ The Internal Enlargement of the European Union, Centre Maurits Coppieters Foundation [1] Archived 3 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- ^ "英語ぺらぺら君中級編で余った時間を有効活用する". www.euinternalenlargement.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "The presidency of the Council of the EU". Europa (web portal). The Council of the EU. 2 May 2016. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

The presidency of the Council rotates among the EU member states every 6 months

- ^ "European Union – Guide". politics.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

Member states take it in turns to assume the presidency of the Council of Ministers for six months at a time in accordance with a pre-established rota.

- ^ "The European Parliament: Historical Background". Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Previous UK European elections". BBC News. 2 June 1999. Archived from the original on 24 April 2003. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

The 1951 treaty which created the European Coal and Steel Community (a precursor to the European Economic Community and later European Union) provided for a representative assembly of members drawn from the participating nations' national parliaments. In June 1979, the nine EEC countries held the first direct elections to the European Parliament.

- ^ "Governing Council". European Central Bank. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Peel, Q; et al. (26 March 2010). "Deal shows Merkel has staked out strong role]". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Cooper, Robert (7 April 2002) Why we still need empires Archived 21 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian (London)

- ^ ECJ opinion on Costa vs ENEL Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Eur-Lex

- ^ Judgment of the Court of 15 July 1964. Flaminio Costa v E.N.E.L. Reference for a preliminary ruling: Giudice conciliatore di Milano - Italy. Case 6-64. Archived 29 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Eur-Lex

- ^ "Primacy of EU law (precedence, supremacy) - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "The European Commission decides to refer POLAND to the Court of Justice of the European Union for violations of EU law by its Constitutional Tribunal". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Consolidated versions of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union - Tables of equivalences Archived 27 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Eur-Lex

- ^ As outlined in Title I of Part I of the consolidated Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ^ Kirschbaum, Erik (3 July 2011) Kirschbaum, Erik (3 July 2011). "Greek sovereignty to be massively limited: Juncker". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Mahony, Honor (4 July 2011) Greece faces 'massive' loss of sovereignty Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, EUobserver

- ^ a b Athens becomes EU 'protectorate' Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine To Ethnos via PressEurop 4 July 2011

- ^ Fitzgerald, Kyran (15 October 2011) Reform agenda's leading light Archived 23 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Irish Examiner

- ^ Coy, Peter (13 January 2011) If Demography Is Destiny, Then India Has the Edge Archived 6 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg

- ^ Mahler et al (2 September 2010) How Brussels Is Trying to Prevent a Collapse of the Euro Archived 10 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Der Spiegel

- ^ The Economic Protectorate Archived 8 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Open Europe (4 February 2010)

- ^ Phillips, Leigh (7 September 2011). "Netherlands: Indebted states must be made 'wards' of the commission or leave euro". EU Observer. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "20 member states confirm the creation of an European Public Prosecutor's Office". Council of the European Union. 12 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Eder, Florian (13 September 2017). "Juncker to oppose multispeed Europe". Politico. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Macron revives multi-speed Europe idea Archived 29 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, EUObserver 30 August 2017

- ^ "Freedom in the World 2018: Democracy in Crisis". Freedom House. 2018. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Freedom in the World 2018: Table of Country Scores". Freedom House. 2018. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018.

- ^ McGarry, John (2010). Weller, Marc; Nobbs, Katherine (eds.). Asymmetric Autonomy and the Settlement of Ethnic Conflicts. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 148–179. ISBN 978-0-8122-4230-0.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

[edit]Member state of the European Union

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Legal Framework

Accession Criteria and Process

The accession criteria for membership in the European Union, formally known as the Copenhagen criteria, were defined by the European Council at its meeting in Copenhagen on 21–22 June 1993.[7] These criteria establish three principal conditions that candidate countries must satisfy: political, economic, and administrative. Politically, candidates must possess stable institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights, and respect for and protection of minorities.[8] Economically, they require a functioning market economy capable of withstanding the competitive pressures of the EU's internal market.[9] Administratively, candidates must demonstrate the ability to assume the obligations of membership, including full adoption of the acquis communautaire—the accumulated body of EU law comprising approximately 35 chapters covering areas such as free movement, competition policy, and environmental standards.[10] These criteria build on Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union, which permits any European state respecting the EU's foundational values—outlined in Article 2 as including human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, and respect for human rights—to apply for membership.[8] In addition to the Copenhagen criteria, the EU emphasizes the principle of own merits, meaning each candidate's progress is assessed individually based on compliance rather than a uniform timetable.[7] The European Commission monitors adherence through annual reports, evaluating reforms in judiciary independence, anti-corruption measures, and economic convergence, with findings informing negotiation benchmarks.[1] While formal criteria prioritize empirical fulfillment, historical accessions—such as those of 2004 and 2007—have revealed that geopolitical factors and member state consensus can influence pacing, though official policy insists on rigorous conditionality to safeguard EU integration.[11] The accession process unfolds in sequential stages, requiring unanimous approval by EU member states at critical junctures.[12] A prospective member first submits a formal application to the Council of the European Union, after which the European Commission prepares an opinion assessing compatibility with the Copenhagen criteria and Article 2 values.[11] The European Council then decides by unanimity whether to grant candidate status, potentially alongside a pre-accession framework providing financial and technical aid via instruments like the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA III), allocated €14.2 billion for 2021–2027 to support reforms.[1] Upon achieving candidate status, negotiations may commence following a unanimous European Council decision, structured around 35 chapters of the acquis.[7] Each chapter opens after screening the candidate's legislation and closes only when the Commission confirms effective implementation, often tied to benchmarks like judicial reforms or fiscal stability.[1] Interim progress reports guide advancements, with temporary derogations possible for sensitive areas such as free movement of persons. The process culminates in an accession treaty, negotiated by the Commission and signed by the presidency, which must be ratified by all member states' parliaments or referenda and the candidate's authorities before entry.[11] As of October 2025, this framework remains unchanged, though recent geopolitical shifts have prompted discussions on accelerating enlargement while reinforcing conditionality.[12]Legal Status and Treaties

Membership in the European Union is established through the ratification of an accession treaty by a candidate state and all existing member states, following negotiations under Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), which permits any European state respecting the EU's values—such as respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, and human rights—to apply for membership.[13][14] Upon ratification, the acceding state becomes fully bound by the EU's founding treaties, including the TEU and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which entered into force on December 1, 2009, via the Treaty of Lisbon, consolidating and amending prior agreements like the Treaty of Rome (1957) and the Maastricht Treaty (1992).[15][16] These treaties delineate the Union's objectives, institutional framework, decision-making processes, and the division of competences between the EU and member states, with member states retaining sovereignty in areas not conferred to the Union.[15] The legal status of member states entails a partial pooling of sovereignty, whereby they commit to the principle of sincere cooperation under Article 4(3) TEU, requiring them to facilitate the achievement of the Union's tasks and refrain from measures that could jeopardize its effectiveness.[17] EU law holds primacy over conflicting national law within the Union's competences, a doctrine affirmed by the Court of Justice of the European Union to ensure uniform application and effectiveness of EU rules, as national courts must disapply inconsistent domestic provisions without awaiting legislative amendment.[18] This supremacy applies to primary law (treaties), secondary law (regulations, directives), and general principles, but member states maintain autonomy in non-EU fields, such as defense policy for most (with exceptions like Denmark's opt-out under Protocol 22 to the TFEU).[18] Accession treaties, such as the 2003 treaty admitting ten states including Poland and Hungary or the 2011 treaty for Croatia, adapt the founding treaties to incorporate new members, often including transitional arrangements for economic alignment or justice systems, and require approval by the European Council, European Parliament, and national ratifications.[19] Withdrawal is governed by Article 50 TEU, invoked by the United Kingdom on March 29, 2017, leading to its exit on January 31, 2020, after negotiating a withdrawal agreement ratified by the European Parliament and member states, demonstrating that membership is voluntary and reversible through a two-year negotiation period extendable by unanimity.[13] As of October 2025, 27 sovereign states hold this status, each represented equally in the European Council while population-weighted in the European Parliament and Council voting.[16]Current Member States

List of Sovereign Members

The European Union consists of 27 sovereign member states, each retaining full sovereignty while delegating specific competences to EU institutions under the treaties.[3] These states are independent nations that have acceded through formal treaty ratification processes, with the United Kingdom's withdrawal on 31 January 2020 reducing the total from 28.[3] [20] The following table enumerates the sovereign members alphabetically, including their dates of accession to the EU (or predecessor communities for founding members). Accession dates mark the point at which each state became bound by EU law and participated fully in its institutions.[3] [21]| Country | Accession Date |

|---|---|

| Austria | 1 January 1995 |

| Belgium | 1 January 1958 |

| Bulgaria | 1 January 2007 |

| Croatia | 1 July 2013 |

| Cyprus | 1 May 2004 |

| Czechia | 1 May 2004 |

| Denmark | 1 January 1973 |

| Estonia | 1 May 2004 |

| Finland | 1 January 1995 |

| France | 1 January 1958 |

| Germany | 1 January 1958 |

| Greece | 1 January 1981 |

| Hungary | 1 May 2004 |

| Ireland | 1 January 1973 |

| Italy | 1 January 1958 |

| Latvia | 1 May 2004 |

| Lithuania | 1 May 2004 |

| Luxembourg | 1 January 1958 |

| Malta | 1 May 2004 |

| Netherlands | 1 January 1958 |

| Poland | 1 May 2004 |

| Portugal | 1 January 1986 |

| Romania | 1 January 2007 |

| Slovakia | 1 May 2004 |

| Slovenia | 1 May 2004 |

| Spain | 1 January 1986 |

| Sweden | 1 January 1995 |

Territories and Associated Regions

Outermost regions of European Union member states are remote territories fully incorporated into the Union, where EU law applies in its entirety subject to derogations permitted under Article 349 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to address challenges such as insularity, remoteness, and economic dependence on the mainland.[23][24] These regions elect representatives to the European Parliament and receive cohesion funding tailored to their needs, with a combined population of approximately 5.5 million as of 2023.[23] The nine outermost regions consist of five French overseas departments or collectivities, two Portuguese autonomous regions, and one Spanish autonomous community.| Outermost Region | Member State | Location |

|---|---|---|

| French Guiana | France | South America |

| Guadeloupe | France | Caribbean |

| Martinique | France | Caribbean |

| Mayotte | France | Indian Ocean |

| Réunion | France | Indian Ocean |

| Saint-Martin | France | Caribbean |

| Azores | Portugal | North Atlantic |

| Madeira | Portugal | North Atlantic |

| Canary Islands | Spain | North Atlantic |

| OCT | Member State | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Greenland | Denmark | Arctic |

| Aruba | Netherlands | Caribbean |

| Bonaire | Netherlands | Caribbean |

| Curaçao | Netherlands | Caribbean |

| Saba | Netherlands | Caribbean |

| Sint Eustatius | Netherlands | Caribbean |

| Sint Maarten | Netherlands | Caribbean |

| French Polynesia | France | Pacific |

| French Southern and Antarctic Territories | France | Antarctic/Southern Ocean |

| New Caledonia | France | Pacific |

| Saint Barthélemy | France | Caribbean |

| Saint Pierre and Miquelon | France | North Atlantic |

| Wallis and Futuna | France | Pacific |

Historical Changes in Membership

Founding and Early Enlargements

The origins of what became the European Union trace to the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), established by the Treaty of Paris signed on 18 April 1951 by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany).[27] The treaty entered into force on 23 July 1952, creating a supranational authority to oversee coal and steel production among the six signatories, with the explicit aim of making war between France and Germany "not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible" through economic interdependence.[28] This framework pooled resources in key war-related industries, marking the first institutional step toward continental integration following World War II devastation. The same six nations advanced integration via the Treaty of Rome, signed on 25 March 1957 and effective from 1 January 1958, which founded the European Economic Community (EEC) alongside the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom).[29] The EEC established a customs union and common market, eliminating internal tariffs and coordinating policies on agriculture, transport, and competition to foster trade and economic convergence.[28] Membership remained limited to these founding states until the 1970s, reflecting a deliberate focus on core Western European democracies with aligned economic structures and post-war recovery priorities. The first enlargement occurred on 1 January 1973, when Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom acceded, expanding the EEC to nine members after negotiations that addressed transitional periods for tariffs and agriculture.[30] This northern enlargement incorporated nations with strong parliamentary traditions and market economies, though the UK's entry involved budgetary rebates to offset its disproportionate contributions.[31] Greece joined as the tenth member on 1 January 1981, following its 1974 restoration of democracy; accession emphasized political stabilization aid but highlighted economic disparities, with Greece receiving extended transition periods for industrial adjustment.[32] The Iberian enlargement followed on 1 January 1986, with Portugal and Spain becoming the eleventh and twelfth members after their respective democratic transitions from authoritarian regimes in 1974 and 1975.[33] Negotiations, spanning from 1978 for Portugal and 1979 for Spain, included safeguards for sensitive sectors like fisheries and agriculture to mitigate impacts on existing members.[34] German reunification on 3 October 1990 integrated the five eastern Länder of the former German Democratic Republic into the Federal Republic, automatically extending EEC membership eastward without a separate accession process, as East Germany acceded under Article 23 of the West German Basic Law.[35] This effectively enlarged the Community's territory and population by about 20% overnight, prompting rapid adaptations in representation and funding. These early expansions prioritized democratic consolidation and economic compatibility, setting precedents for subsequent waves amid varying geopolitical pressures.Post-Cold War Expansions

The end of the Cold War in 1991 facilitated the European Union's expansion beyond its Western European core, incorporating neutral Nordic states and former communist countries from Central and Eastern Europe, as well as Mediterranean islands, to foster democratic consolidation, economic integration, and geopolitical stability across the continent.[30] This period saw four enlargement waves, increasing membership from 12 in 1994 to 28 by 2013, with accession requiring candidate states to meet the Copenhagen criteria established in 1993: stable institutions guaranteeing democracy, rule of law, human rights, a functioning market economy, and ability to adopt the EU acquis communautaire.[11] On 1 January 1995, Austria, Finland, and Sweden acceded as the EU's fourth enlargement, raising membership to 15; these neutral countries had applied in the early 1990s amid economic pressures and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, though Norway rejected membership in a referendum for the second time.[11] Austria's accession treaty was signed on 24 June 1994, following negotiations that addressed its federal structure and environmental standards, while Finland and Sweden emphasized opt-outs from the euro and certain justice policies.[36] The fifth enlargement on 1 May 2004 marked the largest single expansion, adding ten states—Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia—doubling the EU's population to over 450 million and integrating eight post-communist economies that had undergone market reforms since 1989.[37] Accession treaties were signed in Athens on 16 April 2003 after negotiations opened in 1998, with transitional measures for agriculture, free movement of workers, and structural funds to ease disparities; Poland, the largest newcomer with 38 million inhabitants, received €2.4 billion annually in cohesion aid initially.[38] Bulgaria and Romania joined on 1 January 2007 as the sixth enlargement, bringing membership to 27; their applications dated to 1995, but progress was delayed by governance and judicial reforms, leading to a Cooperation and Verification Mechanism post-accession to monitor anti-corruption and rule-of-law improvements.[39] Despite safeguards like quotas on labor migration imposed by some members, the accessions added 29 million citizens and emphasized continued alignment with EU standards.[40] Croatia became the 28th member on 1 July 2013, following its 2003 application and negotiations concluded in 2011 amid efforts to resolve border disputes and war crimes prosecutions from the 1990s Yugoslav conflicts.[41] The Treaty of Accession was signed on 9 December 2011, with transitional restrictions on fisheries and shipbuilding, reflecting Croatia's GDP per capita of about 60% of the EU average at entry and its strategic Adriatic position.[42]| Enlargement Wave | Date | New Members | Total Membership After |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fourth | 1 January 1995 | Austria, Finland, Sweden | 15 |

| Fifth | 1 May 2004 | Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia | 25 |

| Sixth | 1 January 2007 | Bulgaria, Romania | 27 |

| Seventh | 1 July 2013 | Croatia | 28 |

Withdrawals and Recent Stagnation

The United Kingdom became the first and only sovereign member state to withdraw from the European Union, invoking Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union on March 29, 2017, following a national referendum on June 23, 2016, in which 51.9% voted to leave.[43] The withdrawal took effect at 11:00 p.m. GMT on January 31, 2020, after ratification of the Withdrawal Agreement, with a transition period extending until December 31, 2020, during which EU law continued to apply.[44] This process stemmed from long-standing debates over sovereignty, immigration controls, and contributions to the EU budget, culminating in the UK's exit from the single market, customs union, and most policy frameworks.[45] Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, provides the sole prior precedent for partial withdrawal, having acceded to the European Economic Community (EEC, predecessor to the EU) alongside Denmark in 1973 but exiting on February 1, 1985, after a 1982 referendum where 53% favored departure primarily over fishing rights disputes and economic autonomy concerns.[46] Denmark retained full membership, and Greenland transitioned to Overseas Countries and Territories status, maintaining certain trade preferences but without participatory rights.[47] No other sovereign member has invoked withdrawal procedures under Article 50, reflecting the high political and economic barriers embedded in EU treaties, which require unanimous consent for exit terms and often result in prolonged negotiations.[48] EU membership has stagnated since Croatia's accession on July 1, 2013, leaving the bloc with 27 sovereign states as of 2025, despite ongoing applications from nine candidates: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, and Ukraine.[12] Accession negotiations, governed by the Copenhagen criteria requiring stable democratic institutions, market economies, and alignment with EU acquis communautaire, have advanced unevenly; for instance, Montenegro has opened all 33 negotiating chapters with seven provisionally closed, while Turkey's talks remain effectively frozen since 2016 due to rule-of-law backsliding.[49][50] This halt arises from dual challenges: candidate countries' persistent deficits in judicial independence, anti-corruption measures, and economic reforms, compounded by EU-internal factors including "enlargement fatigue," rising nationalism, and fragmented decision-making amid crises like the eurozone debt issues and migration surges.[51][52] Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine prompted accelerated candidate status for Kyiv and Moldova in June 2022, alongside Georgia in December 2023, yet full membership timelines extend into the 2030s at earliest, as geopolitical incentives clash with the EU's reluctance to dilute cohesion or absorb fiscal burdens without prior reforms.[53][54] Proposals for "gradual integration" or phased accession without immediate voting rights have emerged to bypass stagnation, but unanimous member state approval remains elusive.[55]Rights and Obligations

Economic and Trade Commitments

Member states commit to forming a customs union as stipulated in Articles 28 to 32 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which prohibits customs duties on imports and exports between themselves and requires the application of a common customs tariff toward third countries.[56] This union, operational since 1968 following the initial implementation phase under the Treaty of Rome, eliminates internal border controls for goods and ensures uniform external protection, with the European Commission managing tariff rates through the Combined Nomenclature system updated annually.[57] Non-compliance, such as unilateral tariff impositions, would violate the treaty and expose states to infringement proceedings by the European Court of Justice.[58] Integral to these commitments is participation in the EU single market for goods, established under Articles 26 and 34-36 TFEU, mandating the free movement of goods by removing quantitative restrictions and measures with equivalent effect, such as discriminatory technical standards or sanitary rules.[59] Member states must harmonize or mutually recognize regulations via directives and regulations, with the Commission enforcing compliance; for instance, over 1,000 infringement cases related to single market rules were pursued between 2010 and 2020. This extends to services under Articles 56-62 TFEU, requiring liberalization of cross-border service provision, though derogations for public policy reasons are narrowly permitted if proportionate and non-discriminatory.[60] Externally, member states delegate authority for the common commercial policy (CCP) to the EU under Articles 206-207 TFEU, granting exclusive competence over trade in goods, services, intellectual property, and foreign direct investment since the Lisbon Treaty entered into force on December 1, 2009.[61] The European Commission negotiates all trade agreements on behalf of the 27 members, ratified collectively, prohibiting individual states from pursuing bilateral deals that could undermine the common tariff or policy uniformity; as of 2025, the EU maintains over 45 trade agreements covering 70 countries, representing 40% of global trade.[62] Member states retain influence through Council approval by qualified majority for mandates and Parliament consent for agreements, ensuring alignment with internal market rules like competition policy under Articles 101-109 TFEU, which bans anti-competitive state aid and cartels affecting trade between states.[63]Political and Judicial Alignment

Member states of the European Union are required to adhere to the foundational values outlined in Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), which include respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, and human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities.[64] These values serve as a prerequisite for membership and underpin political coordination, with persistent breaches potentially triggering Article 7 TEU procedures, allowing the Council to suspend certain rights such as voting in EU decision-making.[65] Politically, alignment manifests in the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), where member states commit to pursuing shared objectives through coordinated actions, decisions adopted by qualified majority voting or unanimity in the Council, and an obligation to refrain from actions undermining EU positions, though "constructive abstention" permits non-participation without blocking consensus.[66] In practice, CFSP alignment involves member states aligning national foreign policies with EU declarations and sanctions regimes, as evidenced by routine Council statements on third-country alignments, though divergences occur in sensitive areas like defense neutrality or bilateral relations.[67] Judicial alignment requires acceptance of the primacy of EU law over conflicting national law, a principle established by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in the 1964 Costa v ENEL ruling, which held that EU treaties create a new legal order where secondary legislation overrides prior or subsequent domestic measures to ensure uniform application.[68] The CJEU exercises jurisdiction through preliminary rulings requested by national courts on EU law interpretation, infringement proceedings initiated by the Commission against non-compliant states, and actions for annulment, compelling member states to transpose directives and apply regulations directly.[69] While this fosters harmonization, tensions arise when national constitutional courts challenge CJEU primacy, as in Germany's Federal Constitutional Court rulings asserting ultra vires limits, highlighting ongoing debates over sovereignty versus supranational authority.[69] Certain opt-outs, such as Denmark's partial exemption from Title V TEU on justice and home affairs, allow limited derogations, but core judicial obligations remain binding for all members to maintain the single market and legal coherence.[70]Fiscal and Monetary Rules

Member states of the European Union are bound by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), a framework established under the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 and reformed in 2024, which mandates fiscal discipline to coordinate national budgets and prevent excessive deficits that could destabilize the euro area.[71] The core numerical fiscal criteria require annual budget deficits not to exceed 3% of gross domestic product (GDP) and public debt not to surpass 60% of GDP, or if above, to diminish at a satisfactory pace toward that threshold.[71] Breaches trigger the excessive deficit procedure (EDP), whereby the European Commission assesses compliance and recommends corrective action plans, potentially leading to sanctions such as fines up to 0.5% of GDP if unaddressed.[71] The 2024 reforms introduced net expenditure targets and multi-year medium-term fiscal-structural plans, allowing greater flexibility for investments in green and digital transitions while emphasizing debt sustainability, though enforcement remains uneven due to political negotiations within the Council.[72] These fiscal obligations apply uniformly to all 27 EU member states, irrespective of euro adoption, to foster overall economic stability and avoid spillover risks from high-debt countries.[73] As of October 2025, several states remain under EDP: France and Italy face ongoing scrutiny for persistent deficits exceeding 3%—France at 5.5% in 2024 and Italy's debt at 140% of GDP—while Belgium, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia have active procedures, highlighting challenges in consistent application amid economic pressures like post-pandemic recovery and energy crises.[71] The European Commission monitors compliance through annual stability or convergence programs submitted by member states, with the Council deciding on EDP steps, a process criticized for leniency toward larger economies due to veto powers.[74] On monetary policy, EU member states commit to the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) framework, with eurozone participants—20 countries as of July 2025, including Bulgaria's accession on January 1, 2025—ceding national monetary sovereignty to the European Central Bank (ECB), which conducts a single monetary policy aimed at price stability with a 2% inflation target over the medium term.[75][76] Non-euro states, such as Denmark (with a permanent opt-out under the Maastricht Treaty), Sweden, Poland, Czechia, and others, maintain independent central banks but must coordinate policies with ECB guidelines and prepare for eventual euro adoption by meeting convergence criteria.[75] To join the eurozone, aspiring members must satisfy the Maastricht convergence criteria: inflation not exceeding by more than 1.5 percentage points the average of the three best-performing EU states; budget deficit under 3% of GDP; debt below or approaching 60% of GDP; stable exchange rates via participation in the exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) for at least two years without devaluation; and long-term interest rates not more than 2 percentage points above the three lowest-inflation states' average.[77] The ECB and Commission jointly assess these biennially, as in the June 2025 Convergence Report, which evaluates legal compatibility and economic indicators but does not compel immediate adoption absent political will, allowing delays in countries like Poland where public opposition persists.[78] Eurozone states relinquish exchange rate flexibility, relying solely on fiscal tools and ECB policy for adjustment, which amplifies the importance of adhering to fiscal rules to mitigate asymmetric shocks.[79]Sovereignty and Competences

Exclusive EU Powers

The European Union's exclusive competences, as defined in Article 3 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), encompass policy areas where the Union holds sole authority to make legal acts and conclude international agreements, prohibiting member states from unilateral action except as expressly delegated by the EU or for implementing Union law.[80] This framework, codified by the Lisbon Treaty effective December 1, 2009, ensures uniformity in critical domains essential to the single market and external relations, with member states ceding sovereignty to prevent fragmentation that could undermine EU objectives.[80] The exclusive areas are enumerated as follows:- Customs union: The EU maintains a common external tariff and unified customs procedures for imports from non-EU countries, eliminating internal border controls on goods since the union's establishment in 1968 under the European Economic Community. Member states cannot impose independent tariffs or quotas, with the European Commission representing the bloc in tariff negotiations via the World Trade Organization.[80]

- Competition rules necessary for the functioning of the internal market: The EU enforces antitrust measures, merger controls, and state aid prohibitions through Regulations such as 1/2003 and 139/2004, with the Commission fining violations exceeding €10 billion in cases like Google Shopping (2017) and Amazon (2021 probes). National authorities assist in enforcement but lack autonomous rulemaking.[80]

- Monetary policy for eurozone members: For the 20 states adopting the euro as of 2024, the European Central Bank sets interest rates and conducts operations under the Eurosystem, as per Article 127 TFEU, with national central banks executing decisions; non-euro members retain full monetary sovereignty.[80]

- Conservation of marine biological resources under the common fisheries policy: The EU sets total allowable catches and quotas annually via Council regulations, managing stocks in EU waters (including the North Sea and Atlantic) through scientific advice from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, with member states handling day-to-day enforcement but bound by EU limits.[80]

- Common commercial policy: The EU negotiates and concludes trade agreements exclusively, covering goods, services, intellectual property, and investment; as of 2023, over 70 such agreements exist, including the EU-Mercosur deal (provisionally agreed 2019), with the Commission acting on behalf of all members post-Lisbon expansion of scope to "trade and trade-related aspects."[80]

Shared and Supporting Competences

In areas of shared competence, the European Union and its member states may both legislate and adopt legally binding acts, but member states cease to have the ability to exercise their competence to the extent that the Union has exercised or intends to exercise its competence, as stipulated in Article 2(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).[81][82] This principle ensures that EU measures take precedence once adopted, limiting national autonomy in harmonized fields while preserving member state authority in unexhausted areas. Shared competences encompass the internal market; social policy for aspects defined in the treaties; economic, social, and territorial cohesion; agriculture and fisheries, excluding conservation of marine biological resources; environment; consumer protection; transport; energy; area of freedom, security, and justice; and common safety concerns in the field of nuclear power, as enumerated in Article 4 TFEU.[81][83] The practical operation of shared competences involves the EU adopting directives or regulations that set minimum standards or full harmonization, after which member states must transpose or implement them, often resulting in uniform application across the bloc. For instance, in environmental policy, the EU has legislated extensively through directives like the 2008 Ambient Air Quality Directive (2008/50/EC), preempting divergent national approaches and requiring states to align air quality standards, though implementation remains a national responsibility subject to EU enforcement via infringement proceedings.[81] In the internal market, EU rules on free movement of goods, services, persons, and capital—codified in Titles II-IV of Part Three TFEU—override conflicting national laws, as affirmed by the Court of Justice of the EU in cases like Cassis de Dijon (Case 120/78, 1979), which established mutual recognition principles.[84] This dynamic has expanded EU influence over time; between 1958 and 2022, shared competence legislation grew significantly, with over 80% of environmental directives adopted post-1992 Maastricht Treaty amendments.[85] Supporting competences, outlined in Article 6 TFEU, allow the EU to carry out actions that support, coordinate, or supplement member states' initiatives without harmonizing national laws or encroaching on state primacy.[86] These include protection and improvement of human health; industry; culture; education, youth, sport, and vocational training; civil protection; and tourism, among others. EU involvement is typically non-binding, such as funding programs like Erasmus+ for education (established 2014, with €26.2 billion budget for 2021-2027) or coordinating responses in health crises via the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (founded 2005).[81][85] Member states retain full legislative authority, with EU actions limited to incentives or best-practice sharing; for example, in culture, the Creative Europe program (2014-2020) provided €1.46 billion in grants but did not impose uniform policies.[87] These competence categories balance supranational integration with national sovereignty, but shared areas have prompted debates on competence creep, where EU measures progressively encroach via broad interpretations of treaty bases, as critiqued in analyses of post-Lisbon (2009) expansions.[88] Member states can challenge overreach through annulment actions under Article 263 TFEU or by withholding consensus in Council voting, yet EU law's primacy—enshrined in Article 4(3) TEU and Costa v ENEL (Case 6/64, 1964)—ensures that once activated, shared competences constrain unilateral national action, affecting policy domains representing approximately 60% of EU legislative output as of 2022.[89][85] In supporting competences, sovereignty remains largely intact, with EU roles confined to facilitation, preserving diverse national approaches in non-economic spheres.[81]National Derogations and Opt-Outs

Certain European Union member states benefit from derogations and opt-outs negotiated during treaty accessions or amendments, allowing them to abstain from specific areas of integration while remaining full members. These arrangements, enshrined in protocols annexed to the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), preserve national sovereignty in sensitive domains such as monetary policy, justice and home affairs, and border controls.[90] Denmark holds the most extensive such provisions, stemming from the 1992 Edinburgh Agreement following the Maastricht Treaty's ratification challenges.[91] Denmark's opt-out from Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), formalized in Protocol No 16 to the TFEU, exempts it from adopting the euro and participating in the third stage of EMU, including the European Central Bank's governance. This derogation, justified by Denmark's maintenance of the krone pegged to the euro via the ERM II mechanism since 1999, was secured after a narrow 1992 referendum rejection of the Maastricht Treaty. As of 2025, Denmark remains outside the eurozone alongside six other non-opted-out states that have yet to meet convergence criteria.[92] Additionally, under Protocol No 22, Denmark maintains a general opt-out from Title V of the TFEU on Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (AFSJ), excluding it from EU measures on asylum, immigration, judicial cooperation in civil and criminal matters, and police cooperation unless it chooses to opt in on a case-by-case basis. Denmark has selectively participated in over 30 AFSJ instruments via opt-ins, such as the Dublin Regulation on asylum responsibility.[91] Its previous defence opt-out under the same protocol, which barred involvement in EU common security and defence policy decisions, was repealed following a June 2022 referendum where 66.9% voted to abolish it, enabling full participation effective July 1, 2022.[93] Ireland's primary derogation is its opt-out from the Schengen acquis, as per Protocol No 21 to the TFEU, originally shared with the United Kingdom to safeguard the Common Travel Area (CTA) facilitating open borders between Ireland, the UK, and associated islands. This exemption permits Ireland to maintain independent border controls and visa policies, diverging from the EU's internal border-free zone encompassing 23 land-border states and four associated non-members. Ireland cooperates with Schengen on external border information exchange via the Schengen Information System but conducts its own checks at EU entry points.[94] While Protocol No 21 also applies to AFSJ, Ireland exercises an opt-in mechanism, participating in most AFSJ legislation, including recent asylum pacts adopted in 2024.[95] Other member states lack formal permanent opt-outs but operate de facto derogations through transitional arrangements or non-fulfillment of entry conditions. Sweden, for instance, retains the krona despite treaty obligations to adopt the euro upon meeting convergence criteria, as it has not entered the Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II) since its 1995 accession—a prerequisite it interprets as voluntary. Similar delays affect Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania, though Croatia joined the eurozone on January 1, 2023.[96] Poland's Protocol No 30 provides interpretive guarantees on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, clarifying non-interference with national constitutional identities, but does not constitute a full opt-out from its applicability.[90] Accession treaties for newer members, such as those for Bulgaria and Romania in 2005, included temporary derogations in areas like free movement of persons and competition policy, phased out by 2014 and ongoing for Schengen full membership as of 2025.[97] These mechanisms underscore differentiated integration, balancing uniformity with national exceptions to facilitate consensus in an increasingly heterogeneous union.Representation and Governance

Participation in EU Institutions

Member states participate in the European Council through their heads of state or government, with one representative per state among the 27 voting members, alongside the European Council President and the European Commission President; this body sets the EU's political direction and priorities, where each state holds an equal voice regardless of size.[98][99] Decisions are typically by consensus, though qualified majority voting applies in specified cases.[100] In the Council of the European Union, each member state is represented by its relevant national minister, forming configurations based on policy areas such as foreign affairs or economic matters; this ensures governmental input into legislation, where votes use qualified majority (requiring 55% of states representing 65% of EU population) or unanimity for sensitive issues like taxation.[101][102] The presidency rotates every six months among states, coordinating agendas and representing the Council externally during that term.[103] The European Parliament provides indirect state participation via the allocation of seats to nationals elected directly by citizens; following the 2024 elections, the 720 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) are distributed under degressive proportionality, granting larger states more seats (e.g., Germany with 96) while ensuring smaller states like Malta receive at least 6, with MEPs acting independently to represent EU-wide interests rather than national mandates.[104][105] National electoral laws govern elections, held every five years, but MEPs join transnational political groups for legislative work.[106] Each member state nominates one Commissioner to the European Commission, forming a college of 27 members led by the President; nominees are proposed by national governments but must be approved by the Parliament after hearings, committing to prioritize EU interests over national ones upon appointment for a five-year term.[107][108] The Commission proposes legislation and enforces EU law, with Commissioners collectively responsible for decisions.[109] Judicial participation occurs in the Court of Justice of the European Union, where the Court of Justice includes one judge per member state (27 total) plus 11 Advocates General, appointed by common accord of governments for six-year renewable terms to interpret EU law; the General Court features two judges per state (54 total) for handling disputes involving individuals or states.[69][110] Judges are selected for independence and legal expertise, ensuring balanced representation without national bias in rulings.[111]Decision-Making Mechanisms