Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

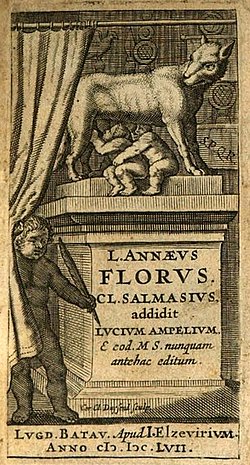

Florus

View on Wikipedia

Three main sets of works are attributed to Florus (a Roman cognomen): Virgilius orator an poeta, the Epitome of Roman History and a collection of 14 short poems (66 lines in all). As to whether these were composed by the same person, or set of people, is unclear, but the works are variously attributed to:

- Publius Annius Florus, described as a Roman poet and rhetorician.

- Julius Florus, described as an ancient Roman poet, orator, and author who was born around 74 AD and died around 130 AD[1] Florus was born in Africa,[1] but raised in Rome.

- Lucius Annaeus Florus (circa 74 – 130 AD[2]), a Roman historian, who lived in the time of Trajan and Hadrian and was also born in Africa.

Virgilius orator an poeta

[edit]

The introduction to a dialogue called Virgilius orator an poeta is extant, in which the author (whose name is given as Publius Annius Florus) states that he was born in Africa, and at an early age took part in the literary contests on the Capitol instituted by Domitian. Having been refused a prize owing to the prejudice against North African provincials, he left Rome in disgust, and after travelling for some time, set up at Tarraco as a teacher of rhetoric. Here he was persuaded by an acquaintance to return to Rome, for it is generally agreed that he is the Florus who wrote the well-known lines quoted together with Hadrian's answer by Aelius Spartianus (Hadrian I 6). Twenty-six trochaic tetrameters, De qualitate vitae, and five graceful hexameters, De rosis, are also attributed to him.[3]

Poems

[edit]Florus was also an established poet.[4] He was once thought to have been "the first in order of a number of second-century North African writers who exercised a considerable influence on Latin literature, and also the first of the poetae neoterici or novelli (new-fashioned poets) of Hadrian's reign, whose special characteristic was the use of lighter and graceful meters (anapaestic and iambic dimeters), which had hitherto found little favour."[3] Since Cameron's article on the topic, however, the existence of such a school has been widely called into question, in part because the remnants of all poets supposedly involved are too scantily attested for any definitive judgment.[5]

The little poems will be found in E. Bahrens, Poëtae Latini minores (1879–1883). There is one 4-line poem in iambic dimeter catalectic; 8 short poems (26 lines in all) in trochaic septenarius; and 5 poems about roses in dactylic hexameters (36 lines in all). For an unlikely identification of Florus with the author of the Pervigilium Veneris see E. H. O. Müller, De P. Anino Floro poéta et de Pervigilio Veneris (1855), and, for the poet's relations with Hadrian, Franz Eyssenhardt, Hadrian und Florus (1882); see also Friedrich Marx in Pauly-Wissowa's Realencyclopädie, i. pt. 2 (1894).[3]

Some his poems include "Quality of Life", "Roses in Springtime", "Roses", "The Rose", "Venus’ Rose-Garden", and "The Nine Muses". Florus’ better-known poetry is also associated with his smaller poems that he would write to Hadrian out of admiration for the emperor.[6]

Epitome of Roman History

[edit]The two books of the Epitome of Roman History were written in admiration of the Roman people.[1] The books illuminate many historical events in a favorable tone for the Roman citizens.[7] The book is mainly based on Livy's enormous Ab Urbe Condita Libri. It consists of a brief sketch of the history of Rome from the foundation of the city to the closing of the Gates of Janus by Augustus in 25 BC. The work, which is called Epitome de T. Livio Bellorum omnium annorum DCC Libri duo, is written in a bombastic and rhetorical style – a panegyric of the greatness of Rome, the life of which is divided into the periods of infancy, youth and manhood.

According to Edward Forster, Florus' history is largely politically unbiased, except when discussing the civil wars where he favours Caesar over Pompey.[8] The first book of the Epitome of Roman History is mainly about the establishment and growth of Rome.[7] The second is mainly about the decline of Rome and its changing morals.[7]

Florus has taken some criticism on his writing due to inaccuracies found chronologically and geographically in his stories,[4] but even so, the Epitome of Roman History was vastly popular during the late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, as well as being used as a school book until the 19th century.[9] In the manuscripts, the writer is variously named as Julius Florus, Lucius Anneus Florus, or simply Annaeus Florus. From certain similarities of style, he has been identified as Publius Annius Florus, poet, rhetorician and friend of Hadrian, author of a dialogue on the question of whether Virgil was an orator or poet, of which the introduction has been preserved.

The most accessible modern text and translation are in the Loeb Classical Library (no. 231, published 1984, ISBN 0-674-99254-7).

Christopher Plantin, Antwerp, in 1567, published two Lucius Florus texts (two title pages) in one volume. The titles were roughly as follows: 1) L.IVLII Flori de Gestis Romanorum, Historiarum; 2) Commentarius I STADII L.IVLII Flori de Gestis Romanorum, Historiarum. The first title has 149 pages; the second has 222 pages plus an index in a 12mo-size book.

Attribution of the works

[edit]Tentative attribution Description Works Dates Other bio Identified with Florus "a Roman historian" Epitome of Roman History circa 74-130 born in Africa; lived in the time of Trajan and Hadrian "In the manuscripts, the writer is variously named as Julius Florus, Lucius Anneus Florus, or simply Annaeus Florus"; "he has been identified as Publius Annius Florus" Julius Florus "an ancient Roman poet, orator, and author" Epitome of Roman History ; poems including "Quality of Life", "Roses in Springtime", "Roses", "The Rose", "Venus’ Rose-Garden", and "The Nine Muses" circa 74-130 born in Africa; accompanied Tiberius to Armenia; lost Domitian's Capital Competition due to prejudice; travelled in the Greek Empire; founded a school in Tarraco, Spain; returned to Rome; a friend of Hadrian "variously identified with Julius Florus, a distinguished orator and uncle of Julius Secundus, an intimate friend of Quintilian (Instit. x. 3, 13); with the leader of an insurrection of the Treviri (Tacitus, Ann. iii. 40); with the Postumus of Horace (Odes, ii. 14) and even with the historian Florus."[10] Publius Annius Florus "Roman poet and rhetorician" Virgilius orator an poeta; 26 trochaic tetrameters, De qualitate vitae, and five graceful hexameters, De rosis born in Africa; accompanied Tiberius to Armenia; lost Domitian's Capital Competition due to prejudice; travelled; founded a school in Tarraco; returned to Rome; knew Hadrian "identified by some authorities with the historian Florus." "generally agreed that he is the Florus who wrote the well-known lines quoted together with Hadrian's answer by Aelius Spartianus" "for an unlikely identification of Florus with the author of the Pervigilium Veneris see E. H. O. Müller"[3]

Tentative biography

[edit]The Florus identified as Julius Florus was one of the young men who accompanied Tiberius on his mission to settle the affairs of Armenia. He has been variously identified with Julius Florus, a distinguished orator and uncle of Julius Secundus, an intimate friend of Quintilian (Instit. x. 3, 13); with the leader of an insurrection of the Treviri (Tacitus, Ann. iii. 40); with the Postumus of Horace (Odes, ii. 14) and even with the historian Florus.[10]

Under Domitian's rule, he competed in the Capital Competition,[4] which was an event in which poets received rewards and recognition from the emperor himself.[4] Although he acquired great applause from the crowds, he was not victorious in the event. Florus himself blamed his loss on favoritism on behalf of the emperor.[9]

Shortly after his defeat, Florus departed from Rome to travel abroad.[9] His travels are said to have taken him through the Greek-speaking sections of the Roman Empire, taking in Sicily, Crete, the Cyclades, Rhodes, and Egypt.[9]

At the conclusion of his travels, he resided in Tarraco, Spain.[4] In Tarraco, Florus founded a school and taught literature.[9] During this time, he also began to write the Epitome of Roman History.[4]

After many years in Spain, he eventually migrated back to Rome during the rule of Hadrian (117-138 AD).[4] Hadrian and Florus became very close friends, and Florus was rumored to be involved in government affairs during the second half of Hadrian's rule.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Epitome of Roman History".

- ^ Saecula Latina (1962), p. 215

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911a.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "LacusCurtius • Florus — Epitome".

- ^ "Cameron, A. "Poetae Novelli" in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 84 (1980), pp. 127-175.

- ^ "Florus: Introduction". Lacus Curtius. 2014. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ a b c Lucius Annaeus, Florus (1929). Epitome of Roman History. London: Heinemann.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Edward S. Forster. "Introduction to Florus' Epitome". LacusCurtius. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "P. Annius Florus". Archived from the original on August 31, 2015.

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911b.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911a). "Florus, Publius Annius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 547.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911b). "Florus, Julius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 547.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jona Lendering. "Publius Annius Florus". Livius.org. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012.

- José Miguel Alonso-Nuñez (2006). "Floro y los historiadores contemporáneos". Acta Classica Universitatis Scientiarum Debreceniensis. 42: 117–126.

- W. den Boer (1972). Some Minor Roman Historians. Leiden: Brill.

- Florus (2005) [c. 120]. Römische Geschichte : lateinisch und deutsch. Eingel., übers. und kommentiert von Günter Laser. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

External links

[edit]- Latin and English texts of Florus, Epitome of Roman History, the 1929 Loeb Classical Library translation by E.S. Forster, Bill Thayer's edition. Lacus Curtius website

- Latin and English texts of Florus's poems. Lacus Curtius website.

Florus

View on GrokipediaIdentity and Attribution

Scholarly Debate on Singularity of Identity

Scholars have long debated whether the Roman poet, rhetorician, and presumed historian known through disparate manuscript traditions constitutes a single figure. The Epitome of Roman History is typically ascribed in surviving manuscripts to Lucius Annaeus Florus or, in some cases, Julius Florus, while the dialogue Virgilius orator an poeta and associated poems are attributed to Publius Annius Florus, dated approximately 74–140 AD.[3][1] This divergence in nomenclature and attribution has fueled questions about singularity, with empirical evidence drawn from textual traditions, chronology, and internal stylistic features rather than explicit ancient biographical linkages. Proponents of a unified identity emphasize chronological compatibility, noting both figures' activity during Emperor Hadrian's reign (117–138 AD), alongside probable North African origins for each. Stylistic analysis reveals shared rhetorical flourishes, such as epigrammatic concision and vivid imagery, alongside lexical overlaps—e.g., recurring terms like virtus and imperium employed in analogous moralizing contexts between the Epitome and the dialogue. These parallels, first systematically argued by 19th-century philologists, suggest a common authorial hand adapting rhetorical training to historical and poetic genres, with name variants (Annius/Annaeus, Publius/Lucius) attributable to scribal confusions or adoptions rather than distinct persons.[4][5] Opposing views highlight persistent onomastic inconsistencies, including the gentilicium shift from Annius to Annaeus (potentially echoing Seneca's family but without direct ties) and praenomen differences, as evidence against conflation. Manuscript traditions for the Epitome and poetic works remain separate, lacking ancient citations that cross-reference the corpora or equate the authors explicitly—e.g., no contemporary like Suetonius or the Historia Augusta merges the identities. While stylistic affinities exist, they may reflect broader Silver Age conventions rather than individual authorship, and the absence of irrefutable proof, despite 19th- and 20th-century syntheses, sustains scholarly division, with some maintaining two or even three contemporaneous Floruses of African provenance.[3][1]Evidence from Manuscripts and Stylistic Analysis

The manuscript tradition of Florus's Epitome of Roman History provides indirect evidence for authorship debates, as no autograph copies survive, with the earliest extant manuscripts dating to the 9th century. The Codex Bambergensis E III 22 (B), a parchment manuscript from the early 9th century, represents the superior textual witness and attributes the work to Iulius Florus, though this praenomen is often viewed as a scribal error or variant lacking firm support from ancient sources.[4] Other key manuscripts, such as the Codex Palatinus Latinus 894 (N) from the Lorsch Monastery (also 9th century), favor Lucius Annaeus Florus, while later copies like the Codex Leidensis Vossianus 14 (L, 11th century) show familial relations but introduce discrepancies traceable to a shared archetype.[4] These variations in nomenclature—ranging from Iulius to Annaeus or Annius—underscore uncertainties in attribution, compounded by the absence of pre-9th-century witnesses, though Jordanes's 6th-century Getica cites a version akin to B, suggesting an older, lost tradition.[4] Stylistic analysis bolsters arguments for a unified authorship encompassing the Epitome and the dialogue Virgilius orator an poeta, revealing consistent markers of rhetorical sophistication. Both works employ brevitas—a deliberate conciseness prioritizing epigrammatic force over exhaustive detail—as seen in the Epitome's abbreviated historical summaries and the dialogue's argumentative framing of Virgil's orator-poet duality.[6] Pointed rhetoric dominates, with moralistic undertones framing Roman history as a panegyric of imperial virtue in the Epitome and ethical debates on literary merit in the dialogue, evoking influences from Virgil, Lucan, and Seneca.[4] Scholarly editions, such as those by Rossbach, highlight lexical and syntactical overlaps, including shared vocabulary for rhetorical flourish (e.g., terms denoting eloquence and moral decay), supporting single-authorship hypotheses despite the works' generic differences.[7] These parallels outweigh divergences, as the Epitome's bombastic tendencies align with the dialogue's performative style, typical of a sophist active in Hadrianic circles.[8] Chronological anchors from internal references further link the texts to a single early 2nd-century composer. The Epitome alludes to "not much less than two hundred years" since Augustus (preface, 1.8), positioning composition in the latter half of Hadrian's reign (c. 117–138 CE) if dated from Augustus's birth (63 BCE) or principate (27 BCE).[4] The Virgilius dialogue, preserved fragmentarily in a Brussels manuscript, reflects contemporaneous imperial interests in Virgil's rhetorical prowess, aligning with Hadrian's era of literary revival and Florus's reported poetic exchanges with the emperor.[5] This temporal convergence, absent contradictory evidence, reinforces attribution to one figure navigating Trajanic-to-Hadrianic transitions, rather than disparate authors.[8]Biography

Origins and Early Life

Florus was born in the Roman province of Africa, likely in the latter half of the first century CE, with some traditions placing his birth around 74 CE.[4][1] Biographical details remain sparse, deriving mainly from manuscript traditions and later chroniclers like Jerome, who note his activity under Hadrian but provide no direct family lineage or senatorial connections beyond the aspirations common to provincial elites.[4] As a youth, Florus traveled to Rome and participated in the Agon Capitolinus, the poetic and rhetorical contests established by Domitian in 86 CE to revive Greek-style games under Roman patronage.[4] This involvement indicates early exposure to competitive declamation and verse composition, aligning with the educational trajectory of ambitious provincials who sought recognition in the imperial capital through public performances.[1] Subsequently, he resided in Tarraco, the administrative center of Hispania Tarraconensis (modern Tarragona, Spain), a hub for rhetorical instruction among the empire's western provinces.[4] There, Florus likely pursued advanced training in oratory and poetry, reflecting standard patterns for Roman elites from peripheral regions who honed skills in declamation to prepare for civic and literary roles, though no specific teachers or institutions are attested.[1]Rhetorical Career and Connections

Florus established himself as a rhetorician in Tarraco, the provincial capital of Hispania Tarraconensis, where he taught and advocated for the profession's merits over mere accumulation of property.[9] In the dialogue Vergilius orator an poeta, attributed to him and set in Tarraco, Florus portrays himself engaging in rhetorical exercises and defending the practical value of teaching literature and declamation, reflecting a focus on applied oratory suited to Roman educational demands rather than esoteric philosophy.[10] This emphasis on declamatory practice aligned with the era's rhetorical training, which prioritized forensic and deliberative speech preparation through improvised themes drawn from history and mythology.[5] His professional networks extended to Rome and imperial circles, evidenced by documented interactions with Emperor Hadrian. Annius Florus, identified as the rhetor, exchanged epigrams with Hadrian, as recorded in the Historia Augusta; Florus composed a verse protesting the rigors of ceaseless travel—"I do not wish to be Caesar, to wander among the Britons, to lurk among the Scythians"—to which Hadrian replied in kind, highlighting taverns and insects as preferable hardships.[11] This exchange indicates Florus's access to the emperor's literary circle, likely as a poet and orator whose wit earned imperial notice, though the Historia Augusta's late composition warrants caution regarding anecdotal embellishments.[12] These court ties appear to have influenced his output, steering him toward genres like abbreviated history that served rhetorical utility and patronage expectations, grounded in verifiable exchanges such as the epigrams rather than unsubstantiated provincial slights or romantic affiliations.[5] No direct evidence confirms denial of Roman rhetorical prizes due to his origins, but his Tarraconensian base underscores the challenges provincials faced in competing at the metropolitan level.[13]Later Years and Possible Patronage

Florus remained active as a writer into the reign of Emperor Hadrian (r. 117–138 AD), with the Epitome of Roman History likely composed between approximately 120 and 130 AD. This dating is supported by the work's rhetorical flourishes characteristic of Hadrianic-era literature and subtle references to the stability of the contemporary empire, contrasting with earlier periods of strife described in the text.[4] [14] The Epitome concludes its narrative with the reign of Augustus but employs phrasing that evokes the Pax Romana extended into Hadrian's time, such as praise for imperial peace without explicit anachronism.[7] Evidence for possible imperial patronage emerges from the identification of Florus with Publius Annius Florus, a poet noted as a friend of Hadrian who exchanged verses with the emperor, as recorded in the Historia Augusta (Hadrian 16). This connection, while debated due to nominal variations, suggests that favor at the imperial court may have contributed to the survival and transmission of Florus's lesser works, including poems and the dialogue Virgilius orator an poeta, amid the selective preservation typical of Roman literature.[4] Such patronage aligns with Hadrian's documented interest in poetry and rhetoric, potentially elevating Florus's profile beyond that of an obscure rhetorician.[15] Florus's death is not directly attested, with estimates placing it around 130–140 AD based on the cessation of his literary activity and absence from subsequent contemporary records, such as those of Antonine biographers. No epitaph, obituary, or personal commemoration survives, reflecting the tentative nature of biographical details for non-elite figures; reliance on cross-references, like the Historia Augusta's biographical notices, underscores the inferential quality of this timeline.[16] The lack of mentions in later sources implies he did not outlive the early Antonine period, consistent with a lifespan commencing circa 74 AD.[17]

.jpg/250px-Lucius_Annaeus_Florus_(74-130).jpg)

.jpg)