Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

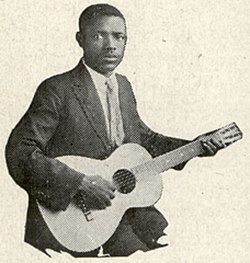

Furry Lewis

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Walter E. "Furry" Lewis (March 6, 1893[1] or 1899[2] – September 14, 1981) was an American country blues guitarist and songwriter from Memphis, Tennessee. He was one of the earliest of the blues musicians active in the 1920s to be brought out of retirement and given new opportunities to record during the folk blues revival of the 1960s.

Life and career

[edit]Lewis was born in Greenwood, Mississippi. His birth year is uncertain. Many sources give 1893, the date he gave in his later years, but researchers Bob Eagle and Eric LeBlanc suggest 1899, based on his 1900 census entry, and other sources suggest 1895 or 1898.[2] His family moved to Memphis when he was age 7.[1] He acquired the nickname Furry from childhood playmates. By 1908, he was playing solo at parties, in taverns, and on the street. He was also invited to play several dates with W. C. Handy's Orchestra.[3]

In his travels as a musician, he was exposed to a wide variety of performers, including Bessie Smith, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and Alger "Texas" Alexander. In 1916,[a] Lewis lost a leg in an accident when trying to jump a freight train in the area around Du Quoin, Illinois, despite having enough cash to pay for a rail ticket.[4] He spent a month in hospital at Carbondale, Illinois recovering, although it took him a year to adjust to his artificial leg and in the meantime he gave up his traveling lifestyle and returned to Memphis, where he performed on street corners.[4] In 1922 he took a permanent position as a street sweeper for the city of Memphis, a job he held until his retirement in 1966, which allowed him to continue performing music in Memphis.[3]

Lewis made his first recordings for Vocalion Records in Chicago in 1927.[5] A year later, he recorded for Victor Records at the Memphis Auditorium in a session with the Memphis Jug Band, Jim Jackson, Frank Stokes, and others. He again recorded for Vocalion in Memphis in 1929.[3] The tracks were mostly blues but included two-part versions of "Casey Jones" and "John Henry". He sometimes fingerpicked and sometimes played with a slide.[6] He made many successful records in the late 1920s, including "Kassie Jones", "Billy Lyons & Stack-O-Lee" and "Judge Harsh Blues" (later called "Good Morning Judge").

On October 3, 1959, Sam Charters, with the assistance of his wife Ann Charters, recorded Furry in his rented room in Memphis, Tennessee. The recordings were released on a Folkways Records LP that same year. On April 3, 1961, Charters again recorded two albums of Furry Lewis - this time at the Sun Studio in Memphis, Tennessee, for the Prestige / Bluesville imprint: "Back on my Feet Again" (BV 1036), and "Done Changed my Mind" (BV 1037). One track was included in Sam and Ann Charters' movie The Blues, finished in 1962, and finding wide release, after being lost for many years, in a 2020 package titled Searching for Secret Heroes by Document Records, thanks to producer Gary Atkinson.

In July 1968, Bob West recorded Furry Lewis along with Bukka White in Lewis's Memphis apartment. In 1972, West, with Bob Graf, in Seattle, released the recording on a 12-inch vinyl record.[7] In 2001 the recording was released on CD as Furry Lewis, Bukka White & Friends, Party! at Home, by Arcola Records.[8]

In 1969, the record producer Terry Manning recorded Lewis in his Fourth Street apartment in Memphis, near Beale Street. These recordings were released in Europe at the time by Barclay Records and again in the early 1990s by Lucky Seven Records in the United States and in 2006 by Universal Records.

In 1972, he was the featured performer in the Memphis Blues Caravan, which included Bukka White, Sleepy John Estes, Clarence Nelson, Hammie Nixon, Memphis Piano Red, Sam Chatmon, and Mose Vinson.[citation needed]

He opened twice for the Rolling Stones, performed on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, had a part in a Burt Reynolds movie (W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, 1975), and was profiled in Playboy magazine.[1][6]

Joni Mitchell's song "Furry Sings the Blues" (on her album Hejira) is about her visit to Lewis's apartment and a mostly ruined Beale Street on February 5, 1976.[3] She wrote "You bring him smoke and drink and he'll play for you, It's mostly muttering now and sideshow spiel, But there was one song he played I could really feel"[9] Lewis hated the Mitchell song and said she should pay him royalties for being its subject.[4]

Lewis began to lose his eyesight because of cataracts in his final years. He contracted pneumonia in 1981, which led to his death from heart failure in Memphis on September 14 of that year at the age of 88.[10] He is buried in the Hollywood Cemetery in South Memphis, where his grave bears two headstones. The second, larger headstone, was purchased by fans.[4]

Discography

[edit]- 1927-29 - Furry's Blues _The Complete Vintage Recordings (Document Recs, 1990/2003)

- 1959 - Furry Lewis (Folkway Recs, 1959)

- 1961 - Back on My Feet Again (Prestige Bluesville, 1961)

- 1961 - Done Changed My Mind (Prestige Bluesville, 1962)

- 1968 - Presenting the Country Blues (?, ?)

- 1969 - Beale Street Blues/ Forth and Bealt (Barclay/Blue Star, ?)

- 1971 - Live at the Gaslight at the Au Go Go (Ampex, 1971)

- Shake 'Em On Down (compilation), 1972

- The Alabama State Troupers Road Show, 1973

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Eder, Bruce (1981). "Furry Lewis: Biography". AllMusic.com. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Eagle, Bob; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues: A Regional Experience. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. pp. 187, 447. ISBN 978-0313344237.

- ^ a b c d Colin Larkin, ed. (1995). The Guinness Who's Who of Blues (Second ed.). Guinness Publishing. p. 237. ISBN 0-85112-673-1.

- ^ a b c d [1] Archived January 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine"Furry Lewis", by Greg Johnson - Article Reprint from the July 2001 BluesNotes, via Cascade Blues Association

- ^ Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books. p. 12. ISBN 1-85868-255-X.

- ^ a b Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books. pp. 134–35. ISBN 1-85868-255-X.

- ^ "popsike.com - SCARCE BLUES LP Furry Lewis & Bukka White ASP1 - auction details". Popsike.com. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "Arcola Records, music cds, Traditional Jazz Blues, Furry Lewis and Friends". Arcolarecords.com. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "Joni Mitchell - Furry Sings The Blues - lyrics". Jonimitchell.com. Retrieved March 6, 2025.

- ^ Doc Rock. "The 1980s". TheDeadRockStarsClub.com. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

External links

[edit]- Fansite reminiscences

- Furry Lewis at Find a Grave

- Mini-biography @ cr.nps.gov Archived February 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Furry Lewis on Myspace

- Mississippi Blues Trail

- Illustrated Furry Lewis discography

- Furry Lewis discography at Discogs

Furry Lewis

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Family Background

Walter E. Lewis, better known as Furry Lewis, was born on March 6, 1893 (though the 1900 census records him as born in 1899), in Greenwood, Mississippi, although some accounts place his birthplace in nearby Greenville.[5][6][7][2] His father, also named Walter Lewis, abandoned the family before his son's birth, leaving young Walter to be raised by his mother, Victoria Coleman, alongside two sisters in conditions of significant poverty typical of sharecropping households in the Mississippi Delta.[6][8] Around 1900, when Lewis was approximately seven years old, his mother relocated the family to Memphis, Tennessee, seeking better opportunities amid ongoing economic hardship; there, Lewis contributed to the household by working as a delivery boy from an early age and acquired the nickname "Furry" from childhood playmates.[6][8][7][2] Formal education for Lewis was limited, as he attended school only through the fifth grade before the demands of family survival and street life in Memphis took precedence, shaping his self-reliant upbringing.[6]Introduction to Music and Early Influences

Walter "Furry" Lewis developed an early interest in music after his family relocated to Memphis, Tennessee, around 1900, providing access to the vibrant musical scene on Beale Street.[3] As a young boy, he constructed his first makeshift guitar from a cigar box and scraps found around the home, beginning his musical journey through self-taught observation of street performers in the area.[9] By around age 14 in 1907, Lewis had debuted on Beale Street, honing his skills by watching and emulating local musicians without formal instruction.[1] Lewis's key influences included mentors from the Memphis blues community, notably Jim Jackson, a prominent songster with whom he later collaborated on traveling medicine shows, and the lively jug band scene that characterized early 20th-century Beale Street entertainment.[10] He also expressed admiration for W.C. Handy, the "Father of the Blues," claiming to have played with Handy, who gifted him his first proper Martin guitar, which elevated his playing capabilities.[11] These figures and the surrounding environment shaped Lewis's approach, blending ragtime elements with emerging blues forms observed in house parties, fish fries, and street gatherings. His early style emerged as a distinctive country blues, characterized by intricate fingerpicking techniques that contrasted with the raw intensity of Delta blues, often employing a slide or bottleneck method for expressive slides.[12] Lewis incorporated humorous, witty lyrics into his songs, drawing from everyday life and storytelling traditions, which added a lighthearted, narrative quality to his performances and set him apart in the Memphis blues landscape.[6] This foundation of relaxed, improvisatory playing and vocal delivery would define his contributions to the genre long before his recording debut.[10]Musical Career

Pre-Recording Performances and 1920s Sessions

Walter E. "Furry" Lewis began his professional music career as a street performer on Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee, debuting around 1907 and continuing through the 1910s and early 1920s.[1] Primarily a solo guitarist, he occasionally joined jug band ensembles, performing with local musicians such as Will Shade and Gus Cannon of the Memphis Jug Band in clubs like Pee Wee's.[13] In the early 1920s, Lewis briefly collaborated with songster Jim Jackson in medicine shows, which helped expand his performance opportunities beyond street corners.[9] Lewis's recording career commenced in 1927 with sessions for Vocalion Records (a Brunswick subsidiary) in Chicago. On April 20, he recorded six titles, including "Rock Island Blues" and "Jelly Roll"; a second session on October 9 yielded seven more, among them "Kassie Jones" (a blues adaptation of the "Casey Jones" ballad) and "Billy Lyons and Stack O'Lee."[5] These 13 sides captured Lewis's distinctive fingerpicking style and narrative songcraft, emblematic of the Memphis country blues tradition.[12] In 1928, Lewis traveled to the Memphis Auditorium for a Victor Records session on August 28, where he cut eight sides, including "Cannon Ball Blues," "Judge Harsh Blues," and further takes of "Kassie Jones."[5] His final pre-revival sessions occurred in September 1929 for Brunswick Records in Memphis, yielding three sides: two takes of "John Henry (The Steel Driving Man)" and "Black Gypsy Blues."[5] This work positioned him amid the late-1920s Memphis blues recording surge, alongside artists like Frank Stokes and the Memphis Jug Band, as labels scouted regional talent.[11] However, his releases saw limited commercial traction amid the era's competitive market and the onset of the Great Depression, resulting in no additional sessions for nearly three decades.[14]Mid-Century Hiatus and Employment

Following his final recording sessions in September 1929 for Brunswick Records, where he cut two takes of "John Henry (The Steel Driving Man)" and "Black Gypsy Blues," Furry Lewis's professional recording career effectively ended as the Great Depression devastated the music industry, leading to a sharp decline in blues record sales and opportunities for artists like him.[13] The economic collapse, which began that year, forced many blues performers to abandon music as a primary livelihood, with shifting public tastes toward other genres further diminishing demand for traditional country blues in the commercial market.[13] Lewis, already balancing music with manual labor, saw his sporadic recording work dry up entirely during this period, reflecting the broader struggles of African American musicians in the South amid widespread unemployment and financial hardship.[1] To support himself, Lewis maintained steady employment with the City of Memphis, joining the sanitation department in 1922 as a street sweeper—a role he held for over four decades until his retirement in 1966 at age 73.[13] His duties involved early-morning shifts cleaning streets, including the iconic Beale Street area, providing reliable income during an era when the instability of performance work made full-time music untenable for most blues artists.[15] This long-term job underscored the economic realities facing early blues musicians, many of whom turned to public service or labor roles to survive the Depression and subsequent decades of limited opportunities in the genre.[13] Despite the hiatus from professional recordings and tours, Lewis continued occasional informal musical performances in Memphis throughout the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, often at local house parties, street corners, and W.C. Handy Park on Beale Street.[13] These low-key gigs allowed him to share his guitar and songwriting skills with community audiences, preserving his connection to the blues tradition without the pressures of commercial viability.[1] However, such activities remained secondary to his sanitation work, with no new releases or extended engagements, highlighting how economic necessity sidelined full-time artistry for Lewis and his contemporaries during this mid-century lull.[13]1960s Revival and Folk Blues Resurgence

In the late 1950s, as interest in traditional American folk music surged, folklorist and author Samuel Charters sought out overlooked blues performers from earlier decades. On October 3, 1959, Charters, assisted by his wife Ann, visited Lewis at his home in Memphis, Tennessee, where they recorded a session that captured his distinctive fingerpicking guitar style and warm vocal delivery.[2] These recordings formed the basis of Lewis's first post-1920s album, Furry Lewis, released by Folkways Records in 1960, which featured tracks like "John Henry" and "Pearlee Blues" drawn from his pre-Depression repertoire.[16] This release marked a pivotal moment in Lewis's career, reintroducing his music to a new generation amid the burgeoning folk blues revival. The success of the Folkways album aligned with the 1960s folk music boom, where audiences embraced acoustic blues as an authentic root of American popular music, often alongside figures like Mississippi John Hurt and Skip James. Lewis's renewed visibility led to additional recordings on the Prestige label's Bluesville imprint, including Back on My Feet Again in 1961, recorded at Sun Studio in Memphis and highlighting his slide guitar work on songs such as "When My Baby Left Me," and Done Changed My Mind later that year. These albums solidified his place in the resurgence, emphasizing his gentle, narrative-driven style that contrasted with the more intense Delta blues contemporaries.[1] By the mid-1960s, Lewis began performing at key folk festivals, contributing to the cultural shift that elevated early blues artists to festival stages and college audiences. This period culminated in broader exposure through US performances and recordings, further cementing his revival.[11]1970s Performances and Media Appearances

In the 1970s, Furry Lewis experienced the height of his late-career resurgence, building on the momentum from his 1960s rediscovery by folk enthusiasts to achieve broader mainstream exposure through live performances and media. He became a sought-after act in blues and rock circuits, captivating audiences with his fingerpicked guitar style and wry, narrative-driven songs rooted in Memphis blues traditions.[1] Lewis's high-profile gigs underscored his crossover appeal. In 1975, he opened for the Rolling Stones at the Liberty Bowl in Memphis, performing before a crowd of over 50,000 and sharing the bill with acts like the J. Geils Band and the Meters, an event that highlighted the blues-rock fusion of the era.[17] He repeated this role in 1978 at the Mid-South Coliseum, again opening for the Stones alongside Etta James, drawing praise from band members like Bill Wyman for his authentic Delta sound.[18] Additionally, Lewis made annual appearances at the Beale Street Music Festival starting in 1977, performing on the historic street where he had debuted decades earlier, including a notable set in 1979 that celebrated Memphis's blues heritage.[19] Media milestones further elevated Lewis's profile. On July 11, 1974, he appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, delivering a memorable performance of classics like "Kassie Jones" that introduced his music to a national television audience and showcased his charismatic stage presence.[12] The following year, in 1975, Lewis portrayed the character "Uncle Furry," a juke joint musician, in the Burt Reynolds comedy film W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, contributing to the soundtrack with "Dirty Car Blues" alongside Jerry Reed and earning acclaim for bringing authentic blues flavor to the production. Amid these engagements, Lewis continued recording, capturing his live energy in intimate settings. In 1972, he released Shake 'Em On Down on Rounder Records, a collection of solo performances featuring tracks like "John Henry" and "When My Baby Left Me," recorded in Memphis to preserve his unaccompanied style.[20] That same year, he participated in the Memphis Blues Caravan tour and contributed to the collaborative album Party! At Home with Bukka White, blending their guitars in a raw, house-party atmosphere.[1] These efforts solidified his role as a bridge between early 20th-century blues and contemporary audiences.Personal Life and Challenges

1917 Train Accident and Disability

In 1917, at approximately age 24, Furry Lewis suffered a severe injury while attempting to hop a moving freight train near Du Quoin, Illinois, during his travels as a young hobo. His foot became caught in a coupling between cars, and as the train accelerated up a grade, his leg was crushed under the wheels, nearly costing him his life.[21] The incident led to the amputation of his left leg below the knee, a life-altering event that occurred far from his early home in Memphis, Tennessee.[12][22] Following the accident, Lewis spent several months hospitalized at the Illinois Central Railroad Hospital in Carbondale, Illinois, where he underwent recovery and was fitted with a wooden prosthesis. He wore this prosthetic leg for the remainder of his life, adapting to its limitations despite ongoing physical challenges. The prosthesis enabled him to maintain mobility, though it required adjustments in his daily movements and activities.[23][3] The disability profoundly influenced Lewis's approach to music, pushing him toward guitar playing as a primary means of livelihood. He learned to perform one-legged, initially sitting down to master the instrument, which shaped his distinctive style of dragging his left arm across the strings for emphasis during live shows. This adaptation not only sustained his street performing in Memphis but also contributed to the rhythmic, mobile quality of his blues delivery, allowing him to continue gigging throughout the South shortly after the accident.[12][3]Daily Life and Relationships

Furry Lewis maintained a modest and stable residence in Memphis, Tennessee, throughout much of his adult life, including a duplex at 811 Mosby Street where he lived during the 1970s.[17] Earlier, he resided on Brinkley Street, reflecting his preference for simple, affordable housing in neighborhoods close to the city's blues heritage areas.[21] His longtime home in one of Memphis's poorer districts near downtown allowed for a low-key existence, centered on routine domesticity rather than extravagance.[24] Lewis led a quiet, unassuming daily life, marked by humor and a gentle demeanor that endeared him to those around him. His long tenure as a Memphis city sanitation worker until his retirement in 1968 provided a steady routine that balanced his personal habits with financial security.[1] Post-retirement, he embraced a relaxed pace, often spending time at home, engaging in light-hearted conversations, and occasionally participating in community programs like anti-poverty education initiatives.[25] Known for his witty interactions, Lewis once quipped on The Tonight Show in 1974 about avoiding marriage, stating, “Why should I marry, when the man next door to me's got a wife?”—a remark that highlighted his playful outlook on personal independence.[26] In terms of relationships, Lewis had no known marriages or children, choosing instead a solitary yet sociable path within Memphis's tight-knit blues circles. He shared close friendships with fellow musicians, notably Bukka White, with whom he maintained a neighborly bond and recorded informal sessions at his apartment in 1968.[27] These ties extended to the broader Memphis blues community, where he enjoyed camaraderie with contemporaries like Sleepy John Estes during shared tours and local gatherings in the 1970s.[1] Lewis's personal sphere emphasized enduring platonic connections over romantic or familial ones, fostering a sense of belonging through mutual respect and shared cultural roots.[14]Death and Legacy

Final Years and Death

In the late 1970s, as Furry Lewis entered his mid-80s, his performances became less frequent due to advancing age and declining health, particularly the onset of cataracts that progressively impaired his vision.[14] In 1968, producer Bob West captured him performing in his Memphis apartment alongside fellow bluesman Bukka White.[28] On August 14, 1981, Lewis sustained severe burns in a fire at his duplex in Memphis, requiring hospitalization that weakened him further.[24] He suffered a heart attack five days before his death and passed away from pneumonia on September 14, 1981, at City of Memphis Hospital, at the age of 88.[29][1] Lewis's funeral took place on September 16, 1981, drawing attendance from the local blues community, including musician Sid Selvidge and members of the Beale Street Caravan.[24] He was initially buried in a pauper's grave at Hollywood Cemetery in Memphis; a larger headstone was later financed and erected by fans to honor his legacy.[30]Posthumous Recognition and Cultural Impact

Furry Lewis was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2012, recognizing his pivotal role in early Memphis blues and his rediscovery during the 1960s folk revival.[11] In 2018, he received further posthumous honors with induction into the Memphis Music Hall of Fame, where he is celebrated as the personification of the city's blues tradition.[1] Cultural tributes to Lewis have extended his legacy beyond blues circles. Joni Mitchell's 1976 song "Furry Sings the Blues," inspired by her encounter with him in Memphis, captures the decline of Beale Street and Lewis's resilient spirit, maintaining his visibility in broader popular music narratives.[31] Additionally, rare 1962 footage of Lewis performing, originally captured in the short film The Blues by folklorist Sam Charters, was restored and reissued in 2020 as part of the documentary Sitting Here Thinking – The Blues of Sam Charters, preserving his authentic country blues style for contemporary audiences.[32] In 2025, a remastered vinyl reissue of his 1961 album Back on My Feet Again was released, further highlighting his influence.[33] Lewis's influence persists as an inspiration for blues revivalists and in the preservation of Memphis country blues within modern genres. His idiosyncratic guitar techniques and humorous lyricism shaped the 1960s-1970s Memphis revival scene, influencing subsequent generations of performers who draw on early 20th-century blues forms.[2] Notably, his legacy has resonated strongly in Memphis's alternative rock community, where artists have incorporated elements of his raw, narrative-driven style into post-1980s indie and experimental sounds, ensuring the endurance of his contributions to regional music heritage.[34]Discography

Original Studio Recordings

Furry Lewis's earliest original studio recordings occurred during two sessions for the Vocalion label (under the Brunswick Recording Corporation) in Chicago in 1927. The first session on April 20 yielded six sides, including "Rock Island Blues," "Everybody's Blues," "Jelly Roll," "Mr. Furry's Blues," and "Sweet Papa Moan," with Lewis providing vocals and guitar, occasionally accompanied by mandolin.[5] The second session on October 9 produced eight additional sides, such as "Good Looking Girl Blues," "Falling Down Blues," "Big Chief Blues," "Billy Lyons and Stack O'Lee," and "Mean Old Bedbug Blues," all featuring Lewis solo on vocals and guitar.[5] Of the 14 sides recorded across these sessions, 10 were issued as 78 rpm singles on Vocalion, marking Lewis's debut as a recording artist and showcasing his distinctive fingerpicking style and narrative songcraft rooted in Memphis blues traditions.| Title | Matrix/Take | Issue Number (Vocalion) | Accompaniment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock Island Blues | C754-C | 1111-A | Vocals, guitar |

| Everybody's Blues | C748-C | 1111-B | Vocals, guitar, mandolin |

| Jelly Roll | C761-C | 1122-A | Vocals, guitar |

| Mr. Furry's Blues | C750-C | 1122-B | Vocals, guitar, mandolin |

| Sweet Papa Moan | C752-C | 1133-A | Vocals, guitar, mandolin |

| Good Looking Girl Blues | C1246-C | 1133-B | Vocals, guitar |

| Falling Down Blues | C1250-C | 1144-A | Vocals, guitar |

| Big Chief Blues | C1252-C | 1144-B | Vocals, guitar |

| Billy Lyons and Stack O'Lee | C1254-C | 1155-A | Vocals, guitar |

| Mean Old Bedbug Blues | C1258-C | 1155-B | Vocals, guitar |

| Title | Matrix/Take | Issue Number (Victor) | Accompaniment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kassie Jones, Pt. 1 | BVE-45431 | V-38519-A | Vocals, guitar |

| Kassie Jones, Pt. 2 | BVE-45432 | V-38519-B | Vocals, guitar |

| Furry's Blues | BVE-45424 | V-38521-A | Vocals, guitar |

| Judge Harsh Blues | BVE-45433 | V-38521-B | Vocals, guitar |

| Title | Duration | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Longing Blues | 2:42 | Song |

| John Henry | 4:51 | Song |

| I Will Turn Your Money Green | 4:41 | Song |

| Early Recording Career | 1:46 | Spoken |

| Pearlee Blues | 4:08 | Song |

| Judge Boushay Blues | 3:42 | Song |

| I'm Going to Brownsville | 3:20 | Song |

| The Medicine Shows | 2:57 | Spoken |

| Kassie Jones (Casey Jones) | 2:58 | Song |

| St. Louis Blues | 4:25 | Song |

| Let Your Money Talk | 3:42 | Song |

| East St. Louis Blues | 3:20 | Song |

| Album Title | Key Tracks Example |

|---|---|

| Back on My Feet Again | John Henry, Shake 'Em On Down, Big Chief Blues, Roberta |

| Done Changed My Mind | Baby You Don't Want Me, Goin' to Kansas City, Judge Boushay Blues, This Time Tomorrow |