Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Delta blues

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2011) |

| Delta blues | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Blues |

| Cultural origins | Early twentieth century Mississippi, U.S. |

| Derivative forms | |

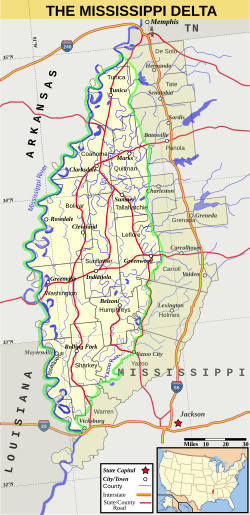

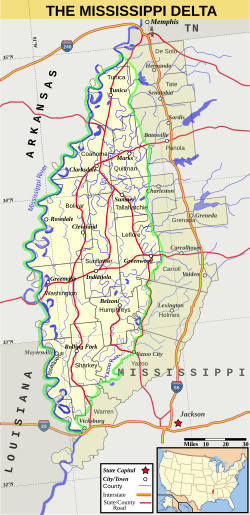

Delta blues is one of the earliest-known styles of blues. It originated in the Mississippi Delta and is regarded as a regional variant of country blues. Guitar and harmonica are its dominant instruments; slide guitar is a hallmark of the style. Vocal styles in Delta blues range from introspective and soulful to passionate and fiery.

Origin

[edit]Although Delta blues certainly existed in some form or another at the turn of the twentieth century, it was first recorded in the late 1920s, when record companies realized the potential African-American market for "race records". The major labels produced the earliest recordings, consisting mostly of one person singing and playing an instrument. Live performances, however, more commonly involved a group of musicians. Record company talent scouts made some of the early recordings on field trips to the South, and some performers were invited to travel to northern cities to record. Current research suggests that Freddie Spruell is the first Delta blues artist to have been recorded; his "Milk Cow Blues" was recorded in Chicago in June 1926.[1] According to Dixon and Godrich (1981), Tommy Johnson and Ishmon Bracey were recorded by Victor on that company's second field trip to Memphis, in 1928. Robert Wilkins was first recorded by Victor in Memphis in 1928, and Big Joe Williams and Garfield Akers by Brunswick/Vocalion, also in Memphis, in 1929.

Charley Patton recorded for Paramount in Grafton, in June 1929 and May 1930. He also traveled to New York City for recording sessions in January and February 1934.

Son House first recorded in Grafton, Wisconsin, in 1930 for Paramount Records.[2]

Robert Johnson recorded his only sessions, in San Antonio in 1936 and in Dallas in 1937, for ARC. Many other artists were recorded during this period.

Subsequently, the early Delta blues (as well as other genres) were extensively recorded by John Lomax and his son Alan Lomax, who crisscrossed the southern U.S. recording music played and sung by ordinary people, helping establish the canon of genres known today as American folk music. Their recordings, numbering in the thousands, now reside in the Smithsonian Institution. According to Dixon and Godrich (1981) and Leadbitter and Slaven (1968), Alan Lomax and the Library of Congress researchers did not record any Delta bluesmen or blueswomen prior to 1941, when he recorded Son House and Willie Brown near Lake Cormorant, Mississippi, and Muddy Waters at Stovall, Mississippi. However, among others, John and Alan Lomax recorded Lead Belly in 1933,[3] and Bukka White in 1939.[4]

Female performers

[edit]In big-city blues, female singers such as Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Mamie Smith dominated the recordings of the 1920s.[5] Although very few women were recorded playing Delta blues and other rural or folk-style blues, many performers did not get professionally recorded.

Geeshie Wiley was a blues singer and guitar player who recorded six songs for Paramount Records that were issued on three records in April 1930. According to the blues historian Don Kent, Wiley "may well have been the rural South's greatest female blues singer and musician".[6]

Memphis Minnie was a blues guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter whose recording career lasted for more than three decades. She recorded approximately 200 songs, some of the best known being "Bumble Bee", "Nothing in Rambling", and "Me and My Chauffeur Blues".

Bertha Lee was a blues singer, active in the 1920s and 1930s. She recorded with and was the common-law wife of, Charley Patton.[7]

Rosa Lee Hill, daughter of Sid Hemphill, learned guitar from her father and by the time she was ten, was playing at dances with him.[8] Several of her songs, such as "Rolled and Tumbled", were recorded by Alan Lomax between 1959 and 1960.[9] In the late 1960s, Jo Ann Kelly (UK) started her recording career.[10] In the 1970s, Bonnie Raitt and Phoebe Snow performed blues.[11]

Bonnie Raitt, Susan Tedeschi and Rory Block are contemporary female blues artists, who were influenced by Delta blues and learned from some of the most notable of the original artists still living. Sue Foley and Shannon Curfman also performed blues music.

Influence

[edit]Many Delta blues artists, such as Big Joe Williams, moved to Detroit and Chicago, creating a pop-influenced city blues style. This was displaced by the new Chicago blues sound in the early 1950s, pioneered by Delta bluesmen Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, and Little Walter, that was harking back to a Delta-influenced sound, but with amplified instruments.

Delta blues was also an inspiration for the creation of British skiffle music, from which eventually came the British invasion bands, while simultaneously influencing British blues that led to the birth of early hard rock and heavy metal.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Leggett, Steve. "Freddie Spruell". AllMusic. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Paramount Records". Msbluestrail.org.

- ^ Richard Havers (September 23, 2022). "The Lomax Legacy: Giving A Voice to the Voiceless". Udiscovermusic.com.

- ^ Annika Van Farowe (February 26, 2018). "Bukka White and the Record Companies". Pages.stolaf.edu.

- ^ Wyman, Havers, Doggett (2001). Bill Wyman's Blues Odyssey. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 77–96.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kent, Don (1994). Liner notes to Mississippi Masters: Early American Blues Classics 1927–35. Reprinted at ParamountsHome.org. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ "Biography by Joslyn Layne". AllMusic. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Liner notes, Lomax Collection, Culturalequity.org

- ^ Lomax, Alan; Hill, Rosa (1959-09-25). "Rolled and tumbled". Alan Lomax Collection.

- ^ Martin, Terry. "Jo Ann Kelly". Martin & Kingsbury. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "Phoebe Snow San Francisco Bay Blues". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cobb, Charles E. Jr. "Traveling the Blues Highway", National Geographic Magazine, April 1999, vol. 195, no. 4.

- Dixon, R. M. W., and Godrich, J. (1981). Blues and Gospel Records: 1902–1943. Storyville: London, ISBN 978-0902391031.

- Ferris, William R. (1988). Blues from the Delta (rev. ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80327-5, ISBN 978-0306803277.

- Ferris, William R. (2009). Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-3325-8, ISBN 978-0807833254 (with CD and DVD).

- Ferris, William R., and Hinson, Glenn (2009). The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Vol. 14: Folklife. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-3346-0, ISBN 978-0-8078-3346-9.

- Gioia, Ted (2009). Delta Blues: The Life and Times of the Mississippi Masters Who Revolutionized American Music. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-33750-2, ISBN 978-0393337501.

- Hamilton, Marybeth. In Search of the Blues, Basic Books, 2009, ISBN 978-0465018123.

- Harris, Sheldon (1979). Blues Who's Who. Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0306801556.

- Leadbitter, M., and Slaven, N. (1968). Blues Records 1943–1966. Oak Publications, London.

- Nicholson, Robert (1999). Mississippi Blues Today! Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80883-8, ISBN 978-0-306-80883-8.

- Palmer, Robert (1982). Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta. Penguin Reprint edition. ISBN 0-14-006223-8, ISBN 978-0-14-006223-6.

- Ramsey, Frederic Jr. (1960). Been Here and Gone. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Idem, Second printing (1969). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Idem, (2000). University of Georgia Press, ISBN 978-0820321950.

- Wilson, Charles Reagan, Ferris, William, Abadie, Ann J. (1989). Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Second Ed. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1823-2, ISBN 978-0-8078-1823-7.