Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

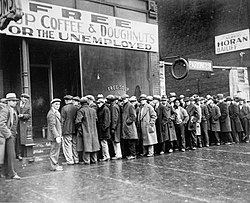

Great Depression

View on Wikipedia

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and business failures around the world. The economic contagion began in 1929 in the United States, the largest economy in the world, with the devastating Wall Street crash of 1929 often considered the beginning of the Depression. Among the countries with the most unemployed were the U.S., the United Kingdom, and Germany.

The Depression was preceded by a period of industrial growth and social development known as the "Roaring Twenties". Much of the profit generated by the boom was invested in speculation, such as on the stock market, contributing to growing wealth inequality. Banks were subject to minimal regulation, resulting in loose lending and widespread debt. By 1929, declining spending had led to reductions in manufacturing output and rising unemployment. Share values continued to rise until the October 1929 crash, after which the slide continued until July 1932, accompanied by a loss of confidence in the financial system. By 1933, the U.S. unemployment rate had risen to 25%, about one-third of farmers had lost their land, and 9,000 of its 25,000 banks had gone out of business. President Herbert Hoover was unwilling to intervene heavily in the economy, and in 1930 he signed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act, which worsened the Depression. In the 1932 presidential election, Hoover was defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt, who from 1933 pursued a set of expansive New Deal programs in order to provide relief and create jobs. In Germany, which depended heavily on U.S. loans, the crisis caused unemployment to rise to nearly 30% and fueled political extremism, paving the way for Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party to rise to power in 1933.

Between 1929 and 1932, worldwide gross domestic product (GDP) fell by an estimated 15%; in the U.S., the Depression resulted in a 30% contraction in GDP.[1] Recovery varied greatly around the world. Some economies, such as the U.S., Germany and Japan started to recover by the mid-1930s; others, like France, did not return to pre-shock growth rates until later in the decade.[2] The Depression had devastating economic effects on both wealthy and poor countries: all experienced drops in personal income, prices (deflation), tax revenues, and profits. International trade fell by more than 50%, and unemployment in some countries rose as high as 33%.[3] Cities around the world, especially those dependent on heavy industry, were heavily affected. Construction virtually halted in many countries, and farming communities and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell by up to 60%.[4][5][6] Faced with plummeting demand and few job alternatives, areas dependent on primary sector industries suffered the most.[7] The outbreak of World War II in 1939 ended the Depression, as it stimulated factory production, providing jobs for women as militaries absorbed large numbers of young, unemployed men.

The precise causes for the Great Depression are disputed. One set of historians, for example, focuses on non-monetary economic causes. Among these, some regard the Wall Street crash itself as the main cause; others consider that the crash was a mere symptom of more general economic trends of the time, which had already been underway in the late 1920s.[3][8] A contrasting set of views, which rose to prominence in the later part of the 20th century,[9] ascribes a more prominent role to failures of monetary policy. According to those authors, while general economic trends can explain the emergence of the downturn, they fail to account for its severity and longevity; they argue that these were caused by the lack of an adequate response to the crises of liquidity that followed the initial economic shock of 1929 and the subsequent bank failures accompanied by a general collapse of the financial markets.[1]

Overview

[edit]The economic picture at the beginning of the crisis

[edit]After the Wall Street crash of 1929, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped from 381 to 198 over the course of two months, optimism persisted for some time. The stock market rose in early 1930, with the Dow returning to 294 (pre-depression levels) in April 1930, before steadily declining for years, to a low of 41 in 1932.[10]

At the beginning, governments and businesses spent more in the first half of 1930 than in the corresponding period of the previous year. On the other hand, consumers, many of whom suffered severe losses in the stock market the previous year, cut expenditures by 10%. In addition, beginning in the mid-1930s, a severe drought ravaged the agricultural heartland of the U.S.[11]

Interest rates dropped to low levels by mid-1930, but expected deflation and the continuing reluctance of people to borrow meant that consumer spending and investment remained low.[12] By May 1930, automobile sales declined to below the levels of 1928. Prices, in general, began to decline, although wages held steady in 1930. Then a deflationary spiral started in 1931. Farmers faced a worse outlook; declining crop prices and a Great Plains drought crippled their economic outlook. At its peak, the Great Depression saw nearly 10% of all Great Plains farms change hands despite federal assistance.[13]

Beyond the United States

[edit]At first, the decline in the U.S. economy was the factor that triggered economic downturns in most other countries due to a decline in trade, capital movement, and global business confidence. Then, internal weaknesses or strengths in each country made conditions worse or better. For example, the U.K. economy, which experienced an economic downturn throughout most of the late 1920s, was less severely impacted by the shock of the depression than the U.S. By contrast, the German economy saw a similar decline in industrial output as that observed in the U.S.[14] Some economic historians attribute the differences in the rates of recovery and relative severity of the economic decline to whether particular countries had been able to effectively devaluate their currencies or not. This is supported by the contrast in how the crisis progressed in, e.g., Britain, Argentina and Brazil, all of which devalued their currencies early and returned to normal patterns of growth relatively rapidly and countries which stuck to the gold standard, such as France or Belgium.[15]

Frantic attempts by individual countries to shore up their economies through protectionist policies – such as the 1930 U.S. Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act and retaliatory tariffs in other countries – exacerbated the collapse in global trade, contributing to the depression.[16] By 1933, the economic decline pushed world trade to one third of its level compared to four years earlier.[17]

| United States | United Kingdom | France | Germany | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial production | −46% | −23% | −24% | −41% |

| Wholesale prices | −32% | −33% | −34% | −29% |

| Foreign trade | −70% | −60% | −54% | −61% |

| Unemployment | +607% | +129% | +214% | +232% |

Course

[edit]

Origins

[edit]While the precise causes for the occurrence of the Great Depression are disputed and can be traced to both global and national phenomena, its immediate origins are most conveniently examined in the context of the U.S. economy, from which the initial crisis spread to the rest of the world.[19]

In the aftermath of World War I, the Roaring Twenties brought considerable wealth to the United States and Western Europe.[20] Initially, the year 1929 dawned with good economic prospects: despite a minor crash on 25 March 1929, the market seemed to gradually improve through September. Stock prices began to slump in September, and were volatile at the end of the month.[21] A large sell-off of stocks began in mid-October. Finally, on 24 October, Black Thursday, the American stock market crashed 11% at the opening bell. Actions to stabilize the market failed, and on 28 October, Black Monday, the market crashed another 12%. The panic peaked the next day on Black Tuesday, when the market saw another 11% drop.[22][23] Thousands of investors were ruined, and billions of dollars had been lost; many stocks could not be sold at any price.[23] The market recovered 12% on Wednesday but by then significant damage had been done. Though the market entered a period of recovery from 14 November until 17 April 1930, the general situation had been a prolonged slump. From September 1929 to 8 July 1932, the market lost 85% of its value.[24]

Despite the crash, the worst of the crisis did not reverberate around the world until after 1929. The crisis hit panic levels again in December 1930, with a bank run on the Bank of United States, a former privately run bank, bearing no relation to the U.S. government (not to be confused with the Federal Reserve). Unable to pay out to all of its creditors, the bank failed.[25][26] Among the 608 American banks that closed in November and December 1930, the Bank of United States accounted for a third of the total $550 million deposits lost and, with its closure, bank failures reached a critical mass.[27]

The Smoot–Hawley Act and the Breakdown of International Trade

[edit]

In an initial response to the crisis, the U.S. Congress passed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act on 17 June 1930. The Act was ostensibly aimed at protecting the American economy from foreign competition by imposing high tariffs on foreign imports. The consensus view among economists and economic historians (including Keynesians, Monetarists and Austrian economists) is that the passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff had, in fact, achieved an opposite effect to what was intended. It exacerbated the Great Depression[28] by preventing economic recovery after domestic production recovered, hampering the volume of trade; still there is disagreement as to the precise extent of the Act's influence.

In a 1995 survey of American economic historians, two-thirds agreed that the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act at least worsened the Great Depression.[29] According to the U.S. Senate website, the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act is among the most catastrophic acts in congressional history.[30]

Many economists have argued that the sharp decline in international trade after 1930 helped to worsen the depression, especially for countries significantly dependent on foreign trade. Most historians and economists blame the Act for worsening the depression by seriously reducing international trade and causing retaliatory tariffs in other countries. While foreign trade was a small part of overall economic activity in the U.S. and was concentrated in a few businesses like farming, it was a much larger factor in many other countries.[31] The average ad valorem (value based) rate of duties on dutiable imports for 1921–1925 was 25.9% but under the new tariff it jumped to 50% during 1931–1935. In dollar terms, American exports declined over the next four years from about $5.2 billion in 1929 to $1.7 billion in 1933; so, not only did the physical volume of exports fall, but also the prices fell by about 1⁄3 as written. Hardest hit were farm commodities such as wheat, cotton, tobacco, and lumber.[32]

Governments around the world took various steps into spending less money on foreign goods such as: "imposing tariffs, import quotas, and exchange controls". These restrictions triggered much tension among countries that had large amounts of bilateral trade, causing major export-import reductions during the depression. Not all governments enforced the same measures of protectionism. Some countries raised tariffs drastically and enforced severe restrictions on foreign exchange transactions, while other countries reduced "trade and exchange restrictions only marginally":[33]

- "Countries that remained on the gold standard, keeping currencies fixed, were more likely to restrict foreign trade." These countries "resorted to protectionist policies to strengthen the balance of payments and limit gold losses." They hoped that these restrictions and depletions would hold the economic decline.[33]

- Countries that abandoned the gold standard allowed their currencies to depreciate which caused their balance of payments to strengthen. It also freed up monetary policy so that central banks could lower interest rates and act as lenders of last resort. They possessed the best policy instruments to fight the Depression and did not need protectionism.[33]

- "The length and depth of a country's economic downturn and the timing and vigor of its recovery are related to how long it remained on the gold standard. Countries abandoning the gold standard relatively early experienced relatively mild recessions and early recoveries. In contrast, countries remaining on the gold standard experienced prolonged slumps."[33]

The gold standard and the spreading of global depression

[edit]The gold standard was the primary transmission mechanism of the Great Depression. Even countries that did not face bank failures and a monetary contraction first-hand were forced to join the deflationary policy since higher interest rates in countries that performed a deflationary policy led to a gold outflow in countries with lower interest rates. Under the gold standard's price–specie flow mechanism, countries that lost gold but nevertheless wanted to maintain the gold standard had to permit their money supply to decrease and the domestic price level to decline (deflation).[34][35]

Gold standard

[edit]

Some economic studies have indicated that the rigidities of the gold standard not only spread the downturn worldwide, but also suspended gold convertibility (devaluing the currency in gold terms) that did the most to make recovery possible.[37]

Every major currency left the gold standard during the Great Depression. The UK was the first to do so. Facing speculative attacks on the pound and depleting gold reserves, in September 1931 the Bank of England ceased exchanging pound notes for gold and the pound was floated on foreign exchange markets. Japan and the Scandinavian countries followed in 1931. Other countries, such as Italy and the United States, remained on the gold standard into 1932 or 1933, while a few countries in the so-called "gold bloc", led by France and including Poland, Belgium and Switzerland, stayed on the standard until 1935–36.[citation needed]

According to later analysis, the earliness with which a country left the gold standard reliably predicted its economic recovery. For example, The UK and Scandinavia, which left the gold standard in 1931, recovered much earlier than France and Belgium, which remained on gold much longer. Countries such as China, which had a silver standard, almost avoided the depression entirely. The connection between leaving the gold standard as a strong predictor of that country's severity of its depression and the length of time of its recovery has been shown to be consistent for dozens of countries, including developing countries. This partly explains why the experience and length of the depression differed between regions and states around the world.[38]

German banking crisis of 1931 and British crisis

[edit]The financial crisis escalated out of control in mid-1931, starting with the collapse of the Credit Anstalt in Vienna in May.[39][40] This put heavy pressure on Germany, which was already in political turmoil. With the rise in violence of National Socialist ('Nazi') and Communist movements, as well as investor nervousness at harsh government financial policies,[41] investors withdrew their short-term money from Germany as confidence spiraled downward. The Reichsbank lost 150 million marks in the first week of June, 540 million in the second, and 150 million in two days, 19–20 June. Collapse was at hand. U.S. President Herbert Hoover called for a moratorium on payment of war reparations. This angered Paris, which depended on a steady flow of German payments, but it slowed the crisis down, and the moratorium was agreed to in July 1931. An International conference in London later in July produced no agreements but on 19 August a standstill agreement froze Germany's foreign liabilities for six months. Germany received emergency funding from private banks in New York as well as the Bank of International Settlements and the Bank of England. The funding only slowed the process. Industrial failures began in Germany, a major bank closed in July and a two-day holiday for all German banks was declared. Business failures were more frequent in July, and spread to Romania and Hungary. The crisis continued to get worse in Germany, bringing political upheaval that finally led to the coming to power of Hitler's Nazi regime in January 1933.[42]

The world financial crisis now began to overwhelm Britain; investors around the world started withdrawing their gold from London at the rate of £2.5 million per day.[43] Credits of £25 million each from the Bank of France and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and an issue of £15 million fiduciary note slowed, but did not reverse, the British crisis. The financial crisis now caused a major political crisis in Britain in August 1931. With deficits mounting, the bankers demanded a balanced budget; the divided cabinet of Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government agreed; it proposed to raise taxes, cut spending, and most controversially, to cut unemployment benefits 20%. The attack on welfare was unacceptable to the Labour movement. MacDonald wanted to resign, but King George V insisted he remain and form an all-party coalition "National Government". The Conservative and Liberals parties signed on, along with a small cadre of Labour, but the vast majority of Labour leaders denounced MacDonald as a traitor for leading the new government. Britain went off the gold standard, and suffered relatively less than other major countries in the Great Depression. In the 1931 British election, the Labour Party was virtually destroyed, leaving MacDonald as prime minister for a largely Conservative coalition.[44][45]

Turning point and recovery

[edit]

In most countries of the world, recovery from the Great Depression began in 1933.[8] In the U.S., recovery began in early 1933,[8] but the U.S. did not return to 1929 GNP for over a decade and still had an unemployment rate of about 15% in 1940, albeit down from the high of 25% in 1933.

There is no consensus among economists regarding the motive force for the U.S. economic expansion that continued through most of the Roosevelt years (and the 1937 recession that interrupted it). The common view among most economists is that Roosevelt's New Deal policies either caused or accelerated the recovery, although his policies were never aggressive enough to bring the economy completely out of recession. Some economists have also called attention to the positive effects from expectations of reflation and rising nominal interest rates that Roosevelt's words and actions portended.[47][48] It was the rollback of those same reflationary policies that led to the interruption of a recession beginning in late 1937.[49][50] One contributing policy that reversed reflation was the Banking Act of 1935, which effectively raised reserve requirements, causing a monetary contraction that helped to thwart the recovery.[51] GDP returned to its upward trend in 1938.[46] A revisionist view among some economists holds that the New Deal prolonged the Great Depression, as they argue that National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and National Labor Relations Act of 1935 restricted competition and established price fixing.[52] John Maynard Keynes did not think that the New Deal under Roosevelt single-handedly ended the Great Depression: "It is, it seems, politically impossible for a capitalistic democracy to organize expenditure on the scale necessary to make the grand experiments which would prove my case—except in war conditions."[53]

According to Christina Romer, the money supply growth caused by huge international gold inflows was a crucial source of the recovery of the United States economy, and that the economy showed little sign of self-correction. The gold inflows were partly due to devaluation of the U.S. dollar and partly due to deterioration of the political situation in Europe.[54] In their book, A Monetary History of the United States, Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz also attributed the recovery to monetary factors, and contended that it was much slowed by poor management of money by the Federal Reserve System. Chairman of the Federal Reserve (2006–2014) Ben Bernanke agreed that monetary factors played important roles both in the worldwide economic decline and eventual recovery.[55] Bernanke also saw a strong role for institutional factors, particularly the rebuilding and restructuring of the financial system,[56] and pointed out that the Depression should be examined in an international perspective.[57]

Role of women and household economics

[edit]Women's primary role was as housewives; without a steady flow of family income, their work became much harder in dealing with food and clothing and medical care. Birthrates fell everywhere, as children were postponed until families could financially support them. The average birthrate for 14 major countries fell 12% from 19.3 births per thousand population in 1930, to 17.0 in 1935.[58] In Canada, half of Roman Catholic women defied Church teachings and used contraception to postpone births.[59]

Among the few women in the labor force, layoffs were less common in the white-collar jobs and they were typically found in light manufacturing work. However, there was a widespread demand to limit families to one paid job, so that wives might lose employment if their husband was employed.[60][61][62] Across Britain, there was a tendency for married women to join the labor force, competing for part-time jobs especially.[63][64]

In France, very slow population growth, especially in comparison to Germany continued to be a serious issue in the 1930s. Support for increasing welfare programs during the depression included a focus on women in the family. The Conseil Supérieur de la Natalité campaigned for provisions enacted in the Code de la Famille (1939) that increased state assistance to families with children and required employers to protect the jobs of fathers, even if they were immigrants.[65]

In rural and small-town areas, women expanded their operation of vegetable gardens to include as much food production as possible. In the United States, agricultural organizations sponsored programs to teach housewives how to optimize their gardens and to raise poultry for meat and eggs.[66] Rural women made feed sack dresses and other items for themselves and their families and homes from feed sacks.[67] In American cities, African American women quiltmakers enlarged their activities, promoted collaboration, and trained neophytes. Quilts were created for practical use from various inexpensive materials and increased social interaction for women and promoted camaraderie and personal fulfillment.[68]

Oral history provides evidence for how housewives in a modern industrial city handled shortages of money and resources. Often they updated strategies their mothers used when they were growing up in poor families. Cheap foods were used, such as soups, beans and noodles. They purchased the cheapest cuts of meat—sometimes even horse meat—and recycled the Sunday roast into sandwiches and soups. They sewed and patched clothing, traded with their neighbors for outgrown items, and made do with colder homes. New furniture and appliances were postponed until better days. Many women also worked outside the home, or took boarders, did laundry for trade or cash, and did sewing for neighbors in exchange for something they could offer. Extended families used mutual aid—extra food, spare rooms, repair-work, cash loans—to help cousins and in-laws.[69]

In Japan, official government policy was deflationary and the opposite of Keynesian spending. Consequently, the government launched a campaign across the country to induce households to reduce their consumption, focusing attention on spending by housewives.[70]

In Germany, the government tried to reshape private household consumption under the Four-Year Plan of 1936 to achieve German economic self-sufficiency. The Nazi women's organizations, other propaganda agencies and the authorities all attempted to shape such consumption as economic self-sufficiency was needed to prepare for and to sustain the coming war. The organizations, propaganda agencies and authorities employed slogans that called up traditional values of thrift and healthy living. However, these efforts were only partly successful in changing the behavior of housewives.[71]

World War II and recovery

[edit]

The common view among economic historians is that the Great Depression ended with the advent of World War II. Many economists believe that government spending on the war caused or at least accelerated recovery from the Great Depression, though some consider that it did not play a very large role in the recovery, though it did help in reducing unemployment.[8][72][73][74]

The rearmament policies leading up to World War II helped stimulate the economies of Europe in 1937–1939. By 1937, unemployment in Britain had fallen to 1.5 million. The mobilization of manpower following the outbreak of war in 1939 ended unemployment.[75]

The American mobilization for World War II at the end of 1941 moved approximately 10 million people out of the civilian labor force and into the war.[76] This finally eliminated the last effects from the Great Depression and brought the U.S. unemployment rate down below 10%.[77]

World War II had a dramatic effect on many parts of the American economy.[78] Government-financed capital spending accounted for only 5% of the annual U.S. investment in industrial capital in 1940; by 1943, the government accounted for 67% of U.S. capital investment.[78] The massive war spending doubled economic growth rates, either masking the effects of the Depression or essentially ending the Depression. Businessmen ignored the mounting national debt and heavy new taxes, redoubling their efforts for greater output to take advantage of generous government contracts.[79]

Causes

[edit]Attempts to return to the Gold Standard

[edit]During World War I, many countries suspended their gold standard in varying ways. There was high inflation from WWI, and in the 1920s in the Weimar Republic, Austria, and throughout Europe. In the late 1920s there was a scramble to deflate prices to get the gold standard's conversation rates back on track to pre-WWI levels, by causing deflation and high unemployment through monetary policy. In 1933 FDR signed Executive Order 6102 and in 1934 signed the Gold Reserve Act.[80]

| Country | Return to Gold | Suspension of Gold Standard | Foreign Exchange Control | Devaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | April 1925 | December 1929 | — | March 1930 |

| Austria | April 1925 | April 1933 | October 1931 | September 1931 |

| Belgium | October 1926 | — | — | March 1935 |

| Canada | July 1926 | October 1931 | — | September 1931 |

| Czechoslovakia | April 1926 | — | September 1931 | February 1934 |

| Denmark | January 1927 | September 1931 | November 1931 | September 1931 |

| Estonia | January 1928 | June 1933 | November 1931 | June 1933 |

| Finland | January 1926 | October 1931 | — | October 1931 |

| France | August 1926 – June 1928 | — | — | October 1936 |

| Germany | September 1924 | — | July 1931 | — |

| Greece | May 1928 | April 1932 | September 1931 | April 1932 |

| Hungary | April 1925 | — | July 1931 | — |

| Italy | December 1927 | — | May 1934 | October 1936 |

| Japan | December 1930 | December 1931 | July 1932 | December 1931 |

| Latvia | August 1922 | — | October 1931 | — |

| Netherlands | April 1925 | — | — | October 1936 |

| Norway | May 1928 | September 1931 | — | September 1931 |

| New Zealand | April 1925 | September 1931 | — | April 1930 |

| Poland | October 1927 | — | April 1936 | October 1936 |

| Romania | March 1927 – February 1929 | — | May 1932 | — |

| Sweden | April 1924 | September 1931 | — | September 1931 |

| Spain | — | — | May 1931 | — |

| United Kingdom | May 1925 | September 1931 | — | September 1931 |

| United States | June 1919 | March 1933 | March 1933 | April 1933 |

Keynesian vs Monetarist view

[edit]

The two classic competing economic theories of the Great Depression are the Keynesian (demand-driven) and the Monetarist explanation.[82] There are also various heterodox theories that downplay or reject the explanations of the Keynesians and monetarists. The consensus among demand-driven theories is that a large-scale loss of confidence led to a sudden reduction in consumption and investment spending. Once panic and deflation set in, many people believed they could avoid further losses by keeping clear of the markets. Holding money became profitable as prices dropped lower and a given amount of money bought ever more goods, exacerbating the drop in demand.[83] Monetarists believe that the Great Depression started as an ordinary recession, but the shrinking of the money supply greatly exacerbated the economic situation, causing a recession to descend into the Great Depression.[84]

Economists and economic historians are almost evenly split as to whether the traditional monetary explanation that monetary forces were the primary cause of the Great Depression is right, or the traditional Keynesian explanation that a fall in autonomous spending, particularly investment, is the primary explanation for the onset of the Great Depression.[85] Today there is also significant academic support for the debt deflation theory and the expectations hypothesis that – building on the monetary explanation of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz – add non-monetary explanations.[86][87]

There is a consensus that the Federal Reserve System should have cut short the process of monetary deflation and banking collapse, by expanding the money supply and acting as lender of last resort. If they had done this, the economic downturn would have been far less severe and much shorter.[88]

Mainstream explanations

[edit]

Modern mainstream economists see the reasons in

- A money supply reduction (Monetarists) and therefore a banking crisis, reduction of credit, and bankruptcies.

- Insufficient demand from the private sector and insufficient fiscal spending (Keynesians).

- Passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act exacerbated what otherwise might have been a more "standard" recession (both Monetarists and Keynesians).[29]

Insufficient spending, the money supply reduction, and debt on margin led to falling prices and further bankruptcies (Irving Fisher's debt deflation).

Monetarist view

[edit]

The monetarist explanation was given by American economists Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz.[89] They argued that the Great Depression was caused by the banking crisis that caused one-third of all banks to vanish, a reduction of bank shareholder wealth and more importantly monetary contraction of 35%, which they called "The Great Contraction". This caused a price drop of 33% (deflation).[90] By not lowering interest rates, by not increasing the monetary base and by not injecting liquidity into the banking system to prevent it from crumbling, the Federal Reserve passively watched the transformation of a normal recession into the Great Depression. Friedman and Schwartz argued that the downward turn in the economy, starting with the stock market crash, would merely have been an ordinary recession if the Federal Reserve had taken aggressive action.[91][92] This view was endorsed in 2002 by Federal Reserve Governor Ben Bernanke in a speech honoring Friedman and Schwartz with this statement:

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression, you're right. We did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.

The Federal Reserve allowed some large public bank failures – particularly that of the New York Bank of United States – which produced panic and widespread runs on local banks, and the Federal Reserve sat idly by while banks collapsed. Friedman and Schwartz argued that, if the Fed had provided emergency lending to these key banks, or simply bought government bonds on the open market to provide liquidity and increase the quantity of money after the key banks fell, all the rest of the banks would not have fallen after the large ones did, and the money supply would not have fallen as far and as fast as it did.[95]

With significantly less money to go around, businesses could not get new loans and could not even get their old loans renewed, forcing many to stop investing. This interpretation blames the Federal Reserve for inaction, especially the New York branch.[96]

One reason why the Federal Reserve did not act to limit the decline of the money supply was the gold standard. At that time, the amount of credit the Federal Reserve could issue was limited by the Federal Reserve Act, which required 40% gold backing of Federal Reserve Notes issued. By the late 1920s, the Federal Reserve had almost hit the limit of allowable credit that could be backed by the gold in its possession. This credit was in the form of Federal Reserve demand notes.[97] A "promise of gold" is not as good as "gold in the hand", particularly when they only had enough gold to cover 40% of the Federal Reserve Notes outstanding. During the bank panics, a portion of those demand notes was redeemed for Federal Reserve gold. Since the Federal Reserve had hit its limit on allowable credit, any reduction in gold in its vaults had to be accompanied by a greater reduction in credit. On 5 April 1933, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102 making the private ownership of gold certificates, coins and bullion illegal, reducing the pressure on Federal Reserve gold.[97]

Keynesian view

[edit]British economist John Maynard Keynes argued in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money that lower aggregate expenditures in the economy contributed to a massive decline in income and to employment that was well below the average. In such a situation, the economy reached equilibrium at low levels of economic activity and high unemployment.

Keynes's basic idea was simple: to keep people fully employed, governments have to run deficits when the economy is slowing, as the private sector would not invest enough to keep production at the normal level and bring the economy out of recession. Keynesian economists called on governments during times of economic crisis to pick up the slack by increasing government spending or cutting taxes.

As the Depression wore on, Franklin D. Roosevelt tried public works, farm subsidies, and other devices to restart the U.S. economy, but never completely gave up trying to balance the budget. According to the Keynesians, this improved the economy, but Roosevelt never spent enough to bring the economy out of recession until the start of World War II.[98]

Debt deflation

[edit]

Irving Fisher argued that the predominant factor leading to the Great Depression was a vicious circle of deflation and growing over-indebtedness.[99] He outlined nine factors interacting with one another under conditions of debt and deflation to create the mechanics of boom to bust. The chain of events proceeded as follows:

- Debt liquidation and distress selling

- Contraction of the money supply as bank loans are paid off

- A fall in the level of asset prices

- A still greater fall in the net worth of businesses, precipitating bankruptcies

- A fall in profits

- A reduction in output, in trade and in employment

- Pessimism and loss of confidence

- Hoarding of money

- A fall in nominal interest rates and a rise in deflation adjusted interest rates[99]

During the Crash of 1929 preceding the Great Depression, margin requirements were only 10%.[100] Brokerage firms, in other words, would lend $9 for every $1 an investor had deposited. When the market fell, brokers called in these loans, which could not be paid back.[101] Banks began to fail as debtors defaulted on debt and depositors attempted to withdraw their deposits en masse, triggering multiple bank runs. Government guarantees and Federal Reserve banking regulations to prevent such panics were ineffective or not used. Bank failures led to the loss of billions of dollars in assets.[101]

Outstanding debts became heavier, because prices and incomes fell by 20–50% but the debts remained at the same dollar amount. After the panic of 1929 and during the first 10 months of 1930, 744 U.S. banks failed. (In all, 9,000 banks failed during the 1930s.) By April 1933, around $7 billion in deposits had been frozen in failed banks or those left unlicensed after the March Bank Holiday.[102] Bank failures snowballed as desperate bankers called in loans that borrowers did not have time or money to repay. With future profits looking poor, capital investment and construction slowed or completely ceased. In the face of bad loans and worsening future prospects, the surviving banks became even more conservative in their lending.[101] Banks built up their capital reserves and made fewer loans, which intensified deflationary pressures. A vicious cycle developed and the downward spiral accelerated.

The liquidation of debt could not keep up with the fall of prices that it caused. The mass effect of the stampede to liquidate increased the value of each dollar owed, relative to the value of declining asset holdings. The very effort of individuals to lessen their burden of debt effectively increased it. Paradoxically, the more the debtors paid, the more they owed.[99] This self-aggravating process turned a 1930 recession into a 1933 great depression.

Fisher's debt-deflation theory initially lacked mainstream influence because of the counter-argument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Pure re-distributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects.

Building on both the monetary hypothesis of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz and the debt deflation hypothesis of Irving Fisher, Ben Bernanke developed an alternative way in which the financial crisis affected output. He builds on Fisher's argument that dramatic declines in the price level and nominal incomes lead to increasing real debt burdens, which in turn leads to debtor insolvency and consequently lowers aggregate demand; a further price level decline would then result in a debt deflationary spiral. According to Bernanke, a small decline in the price level simply reallocates wealth from debtors to creditors without doing damage to the economy. But when the deflation is severe, falling asset prices along with debtor bankruptcies lead to a decline in the nominal value of assets on bank balance sheets. Banks will react by tightening their credit conditions, which in turn leads to a credit crunch that seriously harms the economy. A credit crunch lowers investment and consumption, which results in declining aggregate demand and additionally contributes to the deflationary spiral.[103][104][105]

Expectations hypothesis

[edit]Since economic mainstream turned to the new neoclassical synthesis, expectations are a central element of macroeconomic models. According to Peter Temin, Barry Wigmore, Gauti B. Eggertsson and Christina Romer, the key to recovery and to ending the Great Depression was brought about by a successful management of public expectations. The thesis is based on the observation that after years of deflation and a very severe recession important economic indicators turned positive in March 1933 when Franklin D. Roosevelt took office. Consumer prices turned from deflation to a mild inflation, industrial production bottomed out in March 1933, and investment doubled in 1933 with a turnaround in March 1933. There were no monetary forces to explain that turnaround. Money supply was still falling and short-term interest rates remained close to zero. Before March 1933, people expected further deflation and a recession so that even interest rates at zero did not stimulate investment. But when Roosevelt announced major regime changes, people began to expect inflation and an economic expansion. With these positive expectations, interest rates at zero began to stimulate investment just as they were expected to do. Roosevelt's fiscal and monetary policy regime change helped make his policy objectives credible. The expectation of higher future income and higher future inflation stimulated demand and investment. The analysis suggests that the elimination of the policy dogmas of the gold standard, a balanced budget in times of crisis and small government led endogenously to a large shift in expectation that accounts for about 70–80% of the recovery of output and prices from 1933 to 1937. If the regime change had not happened and the Hoover policy had continued, the economy would have continued its free fall in 1933, and output would have been 30% lower in 1937 than in 1933.[106][107][108]

The recession of 1937–1938, which slowed down economic recovery from the Great Depression, is explained by fears of the population that the moderate tightening of the monetary and fiscal policy in 1937 were first steps to a restoration of the pre-1933 policy regime.[109]

Common position

[edit]There is common consensus among economists today that the government and the central bank should work to keep the interconnected macroeconomic aggregates of gross domestic product and money supply on a stable growth path. When threatened by expectations of a depression, central banks should expand liquidity in the banking system and the government should cut taxes and accelerate spending in order to prevent a collapse in money supply and aggregate demand.[110]

At the beginning of the Great Depression, most economists believed in Say's law and the equilibrating powers of the market, and failed to understand the severity of the Depression. Outright leave-it-alone liquidationism was a common position, and was universally held by Austrian School economists.[111] The liquidationist position held that a depression worked to liquidate failed businesses and investments that had been made obsolete by technological development – releasing factors of production (capital and labor) to be redeployed in other more productive sectors of the dynamic economy. They argued that even if self-adjustment of the economy caused mass bankruptcies, it was still the best course.[111]

Economists like Barry Eichengreen and J. Bradford DeLong note that President Herbert Hoover tried to keep the federal budget balanced until 1932, when he lost confidence in his Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon and replaced him.[111][112][113] An increasingly common view among economic historians is that the adherence of many Federal Reserve policymakers to the liquidationist position led to disastrous consequences.[112] Unlike what liquidationists expected, a large proportion of the capital stock was not redeployed but vanished during the first years of the Great Depression. According to a study by Olivier Blanchard and Lawrence Summers, the recession caused a drop of net capital accumulation to pre-1924 levels by 1933.[114] Milton Friedman called leave-it-alone liquidationism "dangerous nonsense".[110] He wrote:

I think the Austrian business-cycle theory has done the world a great deal of harm. If you go back to the 1930s, which is a key point, here you had the Austrians sitting in London, Hayek and Lionel Robbins, and saying you just have to let the bottom drop out of the world. You've just got to let it cure itself. You can't do anything about it. You will only make it worse. ... I think by encouraging that kind of do-nothing policy both in Britain and in the United States, they did harm.[112]

Heterodox theories

[edit]Austrian School

[edit]Two prominent theorists in the Austrian School on the Great Depression include Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek and American economist Murray Rothbard, who wrote America's Great Depression (1963). In their view, much like the monetarists, the Federal Reserve (created in 1913) shoulders much of the blame; however, unlike the Monetarists, they argue that the key cause of the Depression was the expansion of the money supply in the 1920s which led to an unsustainable credit-driven boom.[115]

In the Austrian view, it was this inflation of the money supply that led to an unsustainable boom in both asset prices (stocks and bonds) and capital goods. Therefore, by the time the Federal Reserve tightened in 1928 it was far too late to prevent an economic contraction.[115] In February 1929 Hayek published a paper predicting the Federal Reserve's actions would lead to a crisis starting in the stock and credit markets.[116]

According to Rothbard, the government support for failed enterprises and efforts to keep wages above their market values actually prolonged the Depression.[117] Unlike Rothbard, after 1970 Hayek believed that the Federal Reserve had further contributed to the problems of the Depression by permitting the money supply to shrink during the earliest years of the Depression.[118] However, during the Depression (in 1932[119] and in 1934)[119] Hayek had criticized both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England for not taking a more contractionary stance.[119]

Hans Sennholz argued that most boom and busts that plagued the American economy, such as those in 1819–20, 1839–1843, 1857–1860, 1873–1878, 1893–1897, and 1920–21, were generated by government creating a boom through easy money and credit, which was soon followed by the inevitable bust.[120]

Ludwig von Mises wrote in the 1930s: "Credit expansion cannot increase the supply of real goods. It merely brings about a rearrangement. It diverts capital investment away from the course prescribed by the state of economic wealth and market conditions. It causes production to pursue paths which it would not follow unless the economy were to acquire an increase in material goods. As a result, the upswing lacks a solid base. It is not real prosperity. It is illusory prosperity. It did not develop from an increase in economic wealth, i.e. the accumulation of savings made available for productive investment. Rather, it arose because the credit expansion created the illusion of such an increase. Sooner or later, it must become apparent that this economic situation is built on sand."[121][122]

Marxist

[edit]Marxists generally argue that the Great Depression was the result of the inherent instability of the capitalist mode of production.[123] According to Forbes, "The idea that capitalism caused the Great Depression was widely held among intellectuals and the general public for many decades."[124]

Inequality

[edit]

Two economists of the 1920s, Waddill Catchings and William Trufant Foster, popularized a theory that influenced many policy makers, including Herbert Hoover, Henry A. Wallace, Paul Douglas, and Marriner Eccles. It held the economy produced more than it consumed, because the consumers did not have enough income. Thus the unequal distribution of wealth throughout the 1920s caused the Great Depression.[125][126]

According to this view, the root cause of the Great Depression was a global over-investment in heavy industry capacity compared to wages and earnings from independent businesses, such as farms. The proposed solution was for the government to pump money into the consumers' pockets. That is, it must redistribute purchasing power, maintaining the industrial base, and re-inflating prices and wages to force as much of the inflationary increase in purchasing power into consumer spending. The economy was overbuilt, and new factories were not needed. Foster and Catchings recommended[127] federal and state governments to start large construction projects, a program followed by Hoover and Roosevelt.

Productivity shock

[edit]It cannot be emphasized too strongly that the [productivity, output, and employment] trends we are describing are long-time trends and were thoroughly evident before 1929. These trends are in nowise the result of the present depression, nor are they the result of the World War. On the contrary, the present depression is a collapse resulting from these long-term trends.

The first three decades of the 20th century saw economic output surge with electrification, mass production, and motorized farm machinery, and because of the rapid growth in productivity there was a lot of excess production capacity and the work week was being reduced. The dramatic rise in productivity of major industries in the U.S. and the effects of productivity on output, wages and the workweek are discussed by Spurgeon Bell in his book Productivity, Wages, and National Income (1940).[129]

Effects by country

[edit]

The majority of countries set up relief programs and most underwent some sort of political upheaval, pushing them to the right. Many of the countries in Europe and Latin America, that were democracies, saw their democratic governments overthrown by some form of dictatorship or authoritarian rule, most famously in Germany in 1933. The Dominion of Newfoundland abandoned its autonomy within the British Empire, becoming the only region ever to voluntarily relinquish democracy. There, too, were severe impacts across the Middle East and North Africa, including economic decline which led to social unrest.[130][131]

Argentina

[edit]Decline in foreign trade hit Argentina hard. The British decision to stop importing Argentine beef led to the signing of the Roca–Runciman Treaty, which preserved a quota in exchange for significant concessions to British exports. By 1935, the economy had recovered to 1929 levels, and the same year, the Central Bank of Argentina was formed.[132] However, the Great Depression was the last time when Argentina was one of the richer countries of the world, as it stopped growing in the decades thereafter, and became underdeveloped.[133]

Australia

[edit]

Australia's dependence on agricultural and industrial exports meant it was one of the hardest-hit developed countries.[134] Falling export demand and commodity prices placed massive downward pressures on wages. Unemployment reached a record high of 29% in 1932,[135] with incidents of civil unrest becoming common.[136] After 1932, an increase in wool and meat prices led to a gradual recovery.[137]

Canada

[edit]

Harshly affected by both the global economic downturn and the Dust Bowl, Canadian industrial production had by 1932 fallen to only 58% of its 1929 figure, the second-lowest level in the world after the United States, and well behind countries such as Britain, which fell to only 83% of the 1929 level. Total national income fell to 56% of the 1929 level, again worse than any country apart from the United States. Unemployment reached 27% at the depth of the Depression in 1933.[138]

Chile

[edit]The League of Nations labeled Chile the country hardest-hit by the Great Depression, because 80% of government revenue came from exports of copper and nitrates, which were in low demand. Chile initially felt the impact of the Great Depression in 1930, when GDP dropped 14%, mining income declined 27%, and export earnings fell 28%. By 1932, GDP had shrunk to less than half of what it had been in 1929, exacting a terrible toll in unemployment and business failures.

Influenced profoundly by the Great Depression, many government leaders promoted the development of local industry in an effort to insulate the economy from future external shocks. After six years of government austerity measures, which succeeded in reestablishing Chile's creditworthiness, Chileans elected to office during the 1938–58 period a succession of center and left-of-center governments interested in promoting economic growth through government intervention.

Prompted in part by the devastating 1939 Chillán earthquake, the Popular Front government of Pedro Aguirre Cerda created the Production Development Corporation (Corporación de Fomento de la Producción, CORFO) to encourage with subsidies and direct investments – an ambitious program of import substitution industrialization. Consequently, as in other Latin American countries, protectionism became an entrenched aspect of the Chilean economy.

China

[edit]China was largely unaffected by the Depression, mainly by having stuck to the Silver standard. However, the U.S. silver purchase act of 1934 created an intolerable demand on China's silver coins, and so, in the end, the silver standard was officially abandoned in 1935 in favor of the four Chinese national banks'[which?] "legal note" issues. China and the British colony of Hong Kong, which followed suit in this regard in September 1935, would be the last to abandon the silver standard. In addition, the Nationalist Government also acted energetically to modernize the legal and penal systems, stabilize prices, amortize debts, reform the banking and currency systems, build railroads and highways, improve public health facilities, legislate against traffic in narcotics, and augment industrial and agricultural production. On 3 November 1935, the government instituted the fiat currency (fapi) reform, immediately stabilizing prices and also raising revenues for the government.

European African colonies

[edit]The sharp fall in commodity prices and the steep decline in exports hurt the economies of the European colonies in Africa and Asia.[139][140] The agricultural sector was especially hard-hit. For example, sisal had recently become a major export crop in Kenya and Tanganyika. During the depression, it suffered severely from low prices and marketing problems that affected all colonial commodities in Africa. Sisal producers established centralized controls for the export of their fibre.[141] There was widespread unemployment and hardship among peasants, labourers, colonial auxiliaries, and artisans.[142] The budgets of colonial governments were cut, which forced the reduction in ongoing infrastructure projects, such as the building and upgrading of roads, ports, and communications.[143] The budget cuts delayed the schedule for creating systems of higher education.[144]

The depression severely hurt the export-based Belgian Congo economy because of the drop in international demand for raw materials and for agricultural products. For example, the price of peanuts fell from 125 to 25 centimes. In some areas, as in the Katanga mining region, employment declined by 70%. In the country as a whole, the wage labour force decreased by 72,000 people, and many men returned to their villages. In Leopoldville, the population decreased by 33% because of this labour migration.[145]

Political protests were not common. However, there was a growing demand, that the paternalistic claims be honored by colonial governments to respond vigorously. The theme was, that economic reforms were more urgently needed than political reforms.[146] French West Africa launched an extensive program of educational reform, in which "rural schools", designed to modernize agriculture, would stem the flow of under-employed farm workers to cities where unemployment was high. Students were trained in traditional arts, crafts, and farming techniques and were then expected to return to their own villages and towns.[147]

France

[edit]

The crisis affected France a bit later than other countries, hitting hard around 1931.[148] While the 1920s saw growth at a strong rate of 4.43% per year, during the 1930s rate fell to only 0.63%.[149]

The depression was relatively mild: unemployment levels peaked at less than 5%, the fall in production was at most 20% below the 1929 output. France also had no major banking crisis.[150]

However, the depression had drastic effects on the local economy, and partly explains the February 6, 1934 riots and even more the formation of the Popular Front, led by SFIO socialist leader Léon Blum, which won the elections in 1936. Ultra-nationalist groups also saw increased popularity, though democracy prevailed into World War II.

France's relatively high degree of self-sufficiency meant the damage was considerably less than in neighbouring states like Germany.

Germany

[edit]

The Great Depression hit Germany hard. The impact of the Wall Street crash forced American banks to end the new loans that had been funding the repayments under the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan. The financial crisis escalated out of control in mid-1931, starting with the collapse of the Credit Anstalt in Vienna in May.[40] This put heavy pressure on Germany, which was already in political turmoil with the rise in violence of national socialist and communist movements, as well as with investor nervousness at harsh government financial policies,[41] investors withdrew their short-term money from Germany as confidence spiraled downward. The Reichsbank lost 150 million marks in the first week of June, 540 million in the second, and 150 million in two days, 19–20 June. Collapse was at hand. U.S. President Herbert Hoover called for a moratorium on payment of war reparations. This angered Paris, which depended on a steady flow of German payments, but it slowed the crisis down, and the moratorium was agreed to in July 1931. An international conference in London later in July produced no agreements, but on 19 August, a standstill agreement froze Germany's foreign liabilities for six months. Germany received emergency funding from private banks in New York as well as the Bank of International Settlements and the Bank of England. The funding only slowed the process. Industrial failures began in Germany, a major bank closed in July, and a two-day holiday for all German banks was declared. Business failures became more frequent in July, and spread to Romania and Hungary.[42]

In 1932, 90% of German reparation payments were cancelled (in the 1950s, Germany repaid all its missed reparations debts). Widespread unemployment reached 25%, as every sector was hurt. The government did not increase government spending to deal with Germany's growing crisis, as they were afraid that a high-spending policy could lead to a return of the hyperinflation that had affected Germany in 1923. Germany's Weimar Republic was hit hard by the depression, as American loans to help rebuild the German economy now stopped.[151] The unemployment rate reached nearly 30% in 1932.[152]

The German political landscape was dramatically altered, leading to Adolf Hitler's rise to power. The Nazi Party rose from being peripheral to winning 18.3% of the vote in the September 1930 election, and the Communist Party also made gains, while moderate forces, like the Social Democratic Party, the Democratic Party, and the People's Party lost seats. The next two years were marked by increased street violence between Nazis and Communists, while governments under President Paul von Hindenburg increasingly relied on rule by decree, bypassing the Reichstag.[153] Hitler ran for the Presidency in 1932, and while he lost to the incumbent Hindenburg in the election, it marked a point during which both Nazi Party and the Communist parties rose in the years following the crash to altogether possess a Reichstag majority following the general election in July 1932.[152][154] Although the Nazis lost seats in November 1932 election, they remained the largest party, and Hitler was appointed as Chancellor the following January. The government formation deal was designed to give Hitler's conservative coalition partners many checks on his power, but over the next few months, the Nazis manoeuvred to consolidate a single-party dictatorship.[155]

Hitler followed an economic policy of autarky, creating a network of client states and economic allies in central Europe and Latin America. By cutting wages and taking control of labor unions, plus public works spending, unemployment fell significantly by 1935. Large-scale military spending played a major role in the recovery.[156] The policies had the effect of driving up the cost of food imports and depleting foreign currency reserves, leading to economic impasse by 1936. Nazi Germany faced a choice of either reversing course or pressing ahead with rearmament and autarky. Hitler chose the latter route, which, according to Ian Kershaw, "could only be partially accomplished without territorial expansion" and therefore war.[157][158]

Greece

[edit]The reverberations of the Great Depression hit Greece in 1932. The Bank of Greece tried to adopt deflationary policies to stave off the crises that were going on in other countries, but these largely failed. For a brief period, the drachma was pegged to the U.S. dollar, but this was unsustainable given the country's large trade deficit and the only long-term effects of this were Greece's foreign exchange reserves being almost totally wiped out in 1932. Remittances from abroad declined sharply, and the value of the drachma began to plummet from 77 drachmas to the dollar in March 1931 to 111 drachmas to the dollar in April 1931. This was especially harmful to Greece, as the country relied on imports from the UK, France, and the Middle East for many necessities. Greece went off the gold standard in April 1932, and declared a moratorium on all interest payments. The country also adopted protectionist policies, such as import quotas, which several European countries also did during the period.

Protectionist policies coupled with a weak drachma and the stifling of imports allowed the Greek industry to expand during the Great Depression. In 1939, the Greek industrial output was 179% that of 1928. These industries were for the most part "built on sand", as one report of the Bank of Greece put it, as without massive protection, they would not have been able to survive. Despite the global depression, Greece managed to suffer comparatively little, averaging an average growth rate of 3.5% from 1932 to 1939. The dictatorial regime of Ioannis Metaxas took over the Greek government in 1936, and economic growth was strong in the years leading up to the Second World War.

Iceland

[edit]Iceland's post-World War I prosperity came to an end with the outbreak of the Great Depression. The Depression hit Iceland hard, as the value of exports plummeted. The total value of Icelandic exports fell from 74 million kronur in 1929 to 48 million in 1932, and was not to rise again to the pre-1930 level until after 1939.[159] Government interference in the economy increased: "Imports were regulated, trade with foreign currency was monopolized by state-owned banks, and loan capital was largely distributed by state-regulated funds".[159] Due to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, which cut Iceland's exports of saltfish by half, the Depression lasted in Iceland until the outbreak of World War II (when prices for fish exports soared).[159]

India

[edit]How much India was affected by the Great Depression has been debated. Historians have argued that it slowed long-term industrial development.[160] Apart from two sectors – jute and coal – the economy was little-affected. However, there were major negative impacts on the jute industry, as world demand fell and prices plunged.[161] Otherwise, conditions were fairly stable. Local markets in agriculture and small-scale industry showed modest gains.[162]

Ireland

[edit]Frank Barry and Mary E. Daly have argued that:

- Ireland was a largely agrarian economy, trading almost exclusively with the UK at the time of the Great Depression. Beef and dairy products comprised the bulk of exports, and Ireland fared well relative to many other commodity producers, particularly in the early years of the depression.[163][164][165][166]

Italy

[edit]

The Great Depression hit Italy very hard.[167] As industries came close to failure they were bought out by the banks in a largely illusionary bail-out—the assets used to fund the purchases were largely worthless. This led to a financial crisis peaking in 1932 and major government intervention. The Industrial Reconstruction Institute (IRI) was formed in January 1933 and took control of the bank-owned companies, suddenly giving Italy the largest state-owned industrial sector in Europe (excluding the USSR). IRI did rather well with its new responsibilities—restructuring, modernising and rationalising as much as it could. It was a significant factor in post-1945 development. But it took the Italian economy until 1935 to recover the manufacturing levels of 1930—a position that was only 60% better than that of 1913.[168][169]

Japan

[edit]The Great Depression did not strongly affect Japan. The Japanese economy shrank by 8% during 1929–31. Japan's Finance Minister Takahashi Korekiyo was the first to implement what have come to be identified as Keynesian economic policies: first, by large fiscal stimulus involving deficit spending; and second, by devaluing the currency. Takahashi used the Bank of Japan to sterilize the deficit spending and minimize resulting inflationary pressures. Econometric studies have identified the fiscal stimulus as especially effective.[170]

The devaluation of the currency had an immediate effect. Japanese textiles began to displace British textiles in export markets. The deficit spending proved to be most profound and went into the purchase of munitions for the armed forces. By 1933, Japan was already out of the depression. By 1934, Takahashi realized that the economy was in danger of overheating, and to avoid inflation, moved to reduce the deficit spending that went towards armaments and munitions.

This resulted in a strong and swift negative reaction from nationalists, especially those in the army, culminating in his assassination in the course of the February 26 Incident. This had a chilling effect on all civilian bureaucrats in the Japanese government. From 1934, the military's dominance of the government continued to grow. Instead of reducing deficit spending, the government introduced price controls and rationing schemes that reduced, but did not eliminate inflation, which remained a problem until the end of World War II.

The deficit spending had a transformative effect on Japan. Japan's industrial production doubled during the 1930s. Further, in 1929 the list of the largest firms in Japan was dominated by light industries, especially textile companies (many of Japan's automakers, such as Toyota, have their roots in the textile industry). By 1940 light industry had been displaced by heavy industry as the largest firms inside the Japanese economy.[171]

Latin America

[edit]Because of high levels of U.S. investment in Latin American economies, they were severely damaged by the Depression. Within the region, Chile, Bolivia and Peru were particularly badly affected.[172]

Before the 1929 crisis, links between the world economy and Latin American economies had been established through American and British investment in Latin American exports to the world. As a result, Latin Americans export industries felt the depression quickly. World prices for commodities such as wheat, coffee and copper plunged. Exports from all of Latin America to the U.S. fell in value from $1.2 billion in 1929 to $335 million in 1933, rising to $660 million in 1940.

But on the other hand, the depression led the area governments to develop new local industries and expand consumption and production. Following the example of the New Deal, governments in the area approved regulations and created or improved welfare institutions that helped millions of new industrial workers to achieve a better standard of living.

Netherlands

[edit]

From roughly 1931 to 1937, the Netherlands suffered a deep and exceptionally long depression. This depression was partly caused by the after-effects of the American stock-market crash of 1929, and partly by internal factors in the Netherlands. Government policy, especially the very late dropping of the Gold Standard, played a role in prolonging the depression. The Great Depression in the Netherlands led to some political instability and riots, and can be linked to the rise of the Dutch fascist political party NSB. The depression in the Netherlands eased off somewhat at the end of 1936, when the government finally dropped the Gold Standard, but real economic stability did not return until after World War II.[173]

New Zealand

[edit]New Zealand was especially vulnerable to worldwide depression, as it relied almost entirely on agricultural exports to the United Kingdom for its economy. The drop in exports led to a lack of disposable income from the farmers, who were the mainstay of the local economy. Jobs disappeared and wages plummeted, leaving people desperate and charities unable to cope. Work relief schemes were the only government support available to the unemployed, the rate of which by the early 1930s was officially around 15%, but unofficially nearly twice that level (official figures excluded Māori and women). In 1932, riots occurred among the unemployed in three of the country's main cities (Auckland, Dunedin, and Wellington). Many were arrested or injured through the tough official handling of these riots by police and volunteer "special constables".[174]

Persia

[edit]In Iran, then known as the Imperial State of Persia, the Great Depression had negative impacts on its exports. In 1933 a new concession was signed with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.[175]

Poland

[edit]Poland was affected by the Great Depression longer and stronger than other countries due to inadequate economic response of the government and the pre-existing economic circumstances of the country. At that time, Poland was under the authoritarian rule of Sanacja, whose leader, Józef Piłsudski, was opposed to leaving the gold standard until his death in 1935. As a result, Poland was unable to perform a more active monetary and budget policy. Additionally, Poland was a relatively young country that emerged merely 10 years earlier after being partitioned between German, Russian, and the Austro-Hungarian Empires for over a century. Prior to independence, the Russian part exported 91% of its exports to Russia proper, while the German part exported 68% to Germany proper. After independence, these markets were largely lost, as Russia transformed into USSR that was mostly a closed economy, and Germany was in a tariff war with Poland throughout the 1920s.[176]

Industrial production fell significantly: in 1932 hard coal production was down 27% compared to 1928, steel production was down 61%, and iron ore production noted an 89% decrease.[177] On the other hand, electrotechnical, leather, and paper industries noted marginal increases in production output. Overall, industrial production decreased by 41%.[178] A distinct feature of the Great Depression in Poland was the de-concentration of industry, as larger conglomerates were less flexible and paid their workers more than smaller ones.

Unemployment rate rose significantly (up to 43%) while nominal wages fell by 51% in 1933 and 56% in 1934, relative to 1928. However, real wages fell less due to the government's policy of decreasing cost of living, particularly food expenditures (food prices were down by 65% in 1935 compared to 1928 price levels). Material conditions deprivation led to strikes, some of them violent or violently pacified – like in Sanok (March of the Hungry in Sanok 6 March 1930), Lesko county (Lesko uprising 21 June – 9 July 1932) and Zawiercie (Bloody Friday (1930) 18 April 1930).

To adapt to the crisis, Polish government employed deflation methods such as high interest rates, credit limits and budget austerity to keep a fixed exchange rate with currencies tied to the gold standard. Only in late 1932 did the government effect a plan to fight the economic crisis.[179] Part of the plan was mass public works scheme, employing up to 100,000 people in 1935.[177] After Piłsudski's death, in 1936 the gold standard regime was relaxed, and launching the development of the Central Industrial Region kicked off the economy, to over 10% annual growth rate in the 1936–1938 period.

Portugal

[edit]Already under the rule of a dictatorial junta, the Ditadura Nacional, Portugal suffered no turbulent political effects of the Depression, although António de Oliveira Salazar, already appointed Minister of Finance in 1928 greatly expanded his powers and in 1932 rose to Prime Minister of Portugal to found the Estado Novo, an authoritarian corporatist dictatorship. With the budget balanced in 1929, the effects of the depression were relaxed through harsh measures towards budget balance and autarky, causing social discontent but stability and, eventually, an impressive economic growth.[180]

Puerto Rico

[edit]In the years immediately preceding the depression, negative developments in the island and world economies perpetuated an unsustainable cycle of subsistence for many Puerto Rican workers. The 1920s brought a dramatic drop in Puerto Rico's two primary exports, raw sugar and coffee, due to a devastating hurricane in 1928 and the plummeting demand from global markets in the latter half of the decade. 1930 unemployment on the island was roughly 36% and by 1933 Puerto Rico's per capita income dropped 30% (by comparison, unemployment in the United States in 1930 was approximately 8% reaching a height of 25% in 1933).[181][182] To provide relief and economic reform, the United States government and Puerto Rican politicians such as Carlos Chardon and Luis Muñoz Marín created and administered first the Puerto Rico Emergency Relief Administration (PRERA) 1933 and then in 1935, the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration (PRRA).[183]

Romania

[edit]Romania was also affected by the Great Depression.[184][185]

South Africa

[edit]As world trade slumped, demand for South African agricultural and mineral exports fell drastically. The Carnegie Commission on Poor Whites had concluded in 1931 that nearly one-third of Afrikaners lived as paupers. The social discomfort caused by the depression was a contributing factor in the 1933 split between the "gesuiwerde" (purified) and "smelter" (fusionist) factions within the National Party and the National Party's subsequent fusion with the South African Party.[186][187] Unemployment programs were begun that focused primarily on the white population.[188]

Soviet Union

[edit]The Soviet Union was the only major socialist state in the world and had very little international trade. Its economy was not tied to the rest of the world and was mostly unaffected by the Great Depression.[189]

At the time of the Depression, the Soviet economy was growing steadily, fuelled by intensive investment in heavy industry. The apparent economic success of the Soviet Union at a time when the capitalist world was in crisis led many Western intellectuals to view the Soviet system favorably. Jennifer Burns wrote:

As the Great Depression ground on and unemployment soared, intellectuals began unfavorably comparing their faltering capitalist economy to Russian Communism. Karl Marx had predicted that capitalism would fall under the weight of its own contradictions, and now with the economic crisis gripping the West, his predictions seem to be coming true. By contrast Russia seemed an emblematic modern nation, making the staggering leap from a feudal past to an industrial future with ease.[190]

The early years of the Great Depression caused mass immigration to the Soviet Union, including 10,000 to 15,000 from Finland and thousands more from Poland, Sweden, Germany, and other nearby countries. The Kremlin was at first happy to help these immigrants settle, believing that they were victims of capitalism who had come to help the Soviet cause. However, by 1933, the worst of the Depression had come to an end in many countries, and word had been received that illegal migrants to the Soviet Union were being sent to Siberia.[191] These factors caused immigration to the Soviet Union to slow significantly, and roughly a tenth of Finnish migrants returned to Finland, either legally or illegally.[191]

Spain

[edit]Spain had a relatively isolated economy, with high protective tariffs and was not one of the main countries affected by the Depression. The banking system held up well, as did agriculture.[192]

By far the most serious negative impact came after 1936 from the heavy destruction of infrastructure and manpower by the civil war, 1936–39. Many talented workers were forced into permanent exile. By staying neutral in the Second World War, and selling to both sides[clarification needed], the economy avoided further disasters.[193]

Sweden

[edit]By the 1930s, Sweden had what America's Life magazine called in 1938 the "world's highest standard of living". Sweden was also the first country worldwide to recover completely from the Great Depression. Taking place amid a short-lived government and a less-than-a-decade old Swedish democracy, events such as those surrounding Ivar Kreuger (who eventually committed suicide) remain infamous in Swedish history. The Social Democrats under Per Albin Hansson formed their first long-lived government in 1932 based on strong interventionist and welfare state policies, monopolizing the office of Prime Minister until 1976 with the sole and short-lived exception of Axel Pehrsson-Bramstorp's "summer cabinet" in 1936. During forty years of hegemony, it was the most successful political party in the history of Western liberal democracy.[194]

Thailand

[edit]In Thailand, then known as the Kingdom of Siam, the Great Depression contributed to the end of the absolute monarchy of King Rama VII in the Siamese revolution of 1932.[195]

Turkey