Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

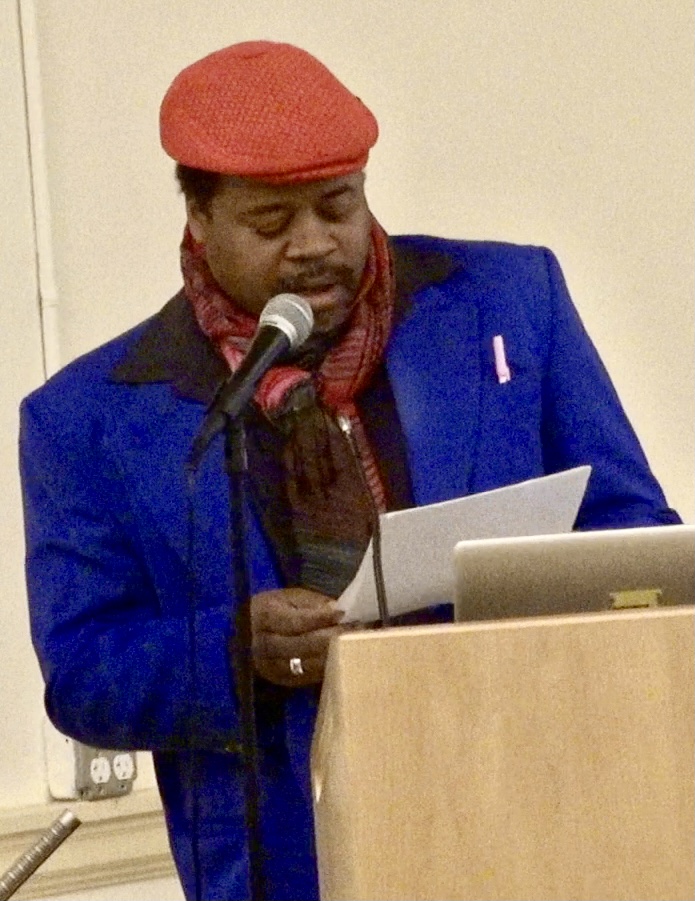

Greg Tate

View on Wikipedia

Gregory Stephen Tate (October 14, 1957 – December 7, 2021) was an American writer, musician, and producer. A long-time critic for The Village Voice, Tate focused particularly on African-American music and culture, helping to establish hip-hop as a genre worthy of music criticism. Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America (1992) collected 40 of his works for the Voice and he published a sequel, Flyboy 2, in 2016. A musician himself, he was a founding member of the Black Rock Coalition and the leader of Burnt Sugar.[1]

Key Information

In 2024, Tate was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize, a Special Citation award.[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Gregory Stephen Tate was born on October 14, 1957,[3] in Dayton, Ohio.[1][4] When he was 13 years old, his family moved to Washington, D.C.[5][6] His parents Charles and Florence (Grinner) Tate were civil rights movement activists involved in the Congress of Racial Equality, and played Malcolm X speeches and Nina Simone's music around the house.[3]

Tate credited Amiri Baraka's Black Music and Rolling Stone, which he first read when he was 14, with stimulating his interest in collecting and writing about music.[7] As a teenager, Tate taught himself how to play guitar. He attended Howard University, where he studied journalism and film.[8]

Career

[edit]Early career and music

[edit]In 1981, following an introduction by family friend Thulani Davis,[3] The Village Voice critic Robert Christgau asked Tate to contribute to the Voice.[9] The following year Tate moved to New York City, where he developed friendships with other musicians, including James "Blood" Ulmer and Vernon Reid.[9] In 1985, he co-founded the Black Rock Coalition (BRC) with some of the African-American musicians he knew who had a common interest in playing rock music, writing in a manifesto that the group "opposes those racist and reactionary forces within the American music industry which undermine and purloin our musical legacy and deny Black artists the expressive freedom and economic rewards that our Caucasian counterparts enjoy as a matter of course".[8][10]

In 1999, Tate established Burnt Sugar, an improvisational ensemble that varies in size between 13 and 35 musicians and blended a range of genres including funk, free jazz, and psychedelic rock.[11][10] Tate, who played guitar and conducted the group,[10][12] described it in 2004 as "a band I wanted to hear but could not find".[13]

Writing

[edit]Though initially a freelancer, Tate quickly became the leading critic on Black culture for the Voice and in that position, one of the leading cultural critics in New York City.[3] He became a staff writer for The Village Voice in 1987, a position he held until 2003.[14] He developed a reputation for "slangy erudition", Hua Hsu wrote: "His best paragraphs throbbed like a party and chattered like a salon; they were stylishly jam-packed with names and reference points that shouldn't have got along but did, a trans-everything collision of pop stars, filmmakers, subterranean graffiti artists, Ivory Tower theorists, and Tate's personal buddies, who often came across as the wisest of the bunch."[12]

Tate's 1986 essay "Cult-Nats Meet Freaky Deke" for the Voice Literary Supplement is widely regarded as a milestone in black cultural criticism;[15] in the essay, he juxtaposed the "somewhat stultified stereotype of the black intellectual as one who operates from a narrow-minded, essentialized notion of black culture" (cultural nationalists, or Cult-Nats) with the freaky "many vibrant colors and dynamics of African American life and art",[16][15] trying to find a middle ground in order to break down "that bastion of white supremacist thinking, the Western art [and literary] world[s]".[17] His work was also published in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Artforum, DownBeat, Essence, JazzTimes, Rolling Stone, and VIBE.[18] At Vibe he became a columnist in 1992, titling his series "Black-Owned".[19] The Source described Tate as one of "the Godfathers of hip hop journalism".[20] A key contribution was his conceptualisation of hip-hop as existing on a continuum with jazz,[12] claiming for the former the level of cultural respect and inquiry the latter commanded.[21]

In 1992, Tate published Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America, a collection of 40 essays on culture and politics, drawn from his writing for the Village Voice.[22][4] Writing for Pitchfork, Allison Hussey said, "It became a definitive work for Tate", treating subjects like Miles Davis, Public Enemy, and Jean Michel Basquiat.[4] Jelani Cobb called the collection "a clinic on literary brilliance" with significant influence on other writers.[10] This impact on subsequent generations of critics was one of Tate's major contributions, with Jon Caramanica writing that "he affected every writer I cared about and learned from — we're all Tate's children."[19]

Tate often had the admiration of the musicians he wrote about, like David Bowie and Flea of Red Hot Chili Peppers; Flea cried in appreciation when Tate reviewed the Peppers' 1999 album Californication.[23]

In 2003, Tate published Everything But the Burden: What White People Are Taking From Black Culture, an edited collection of 18 Black writers addressing the topic of white appropriation of Black art.[24][25] The same year, he published Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix And The Black Experience, an appraisal of the rock legend as a Black icon.[26]

In 2016, Tate published Flyboy 2. In The New Yorker, Hua Hsu wrote that this follow-up to his first collection brought "into sharper focus" Tate's interest in what Tate described as “the way Black people ‘think,’ mentally, emotionally, physically,” and “how those ways of thinking and being inform [their] artistic choices."[12]

Later career

[edit]He was the Louis Armstrong Visiting Professor at Columbia University's Center for Jazz Studies in 2009 and a visiting professor of Africana studies at Brown University in 2012.[18][20] In 2010, he was awarded a United States Artists fellowship.[27]

Personal life

[edit]Tate had a daughter, Chinara Tate, born circa 1979.[28][3] In New York, he was a longtime resident of Harlem.[29]

Tate died of cardiac arrest on December 7, 2021, in New York City, at the age of 64.[3][30] That night, the Apollo Theater in Harlem displayed his name on the marquee in remembrance, its usual response for cultural icons.[29]

Works

[edit]- Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1992. ISBN 0-671-72965-9. Foreword by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

- Editor Everything But the Burden: What White People Are Taking From Black Culture. New York: Broadway Books. 2003. ISBN 0-7679-0808-2.

- Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix and the Black Experience. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books. 2003. ISBN 1-55652-469-2.

- Flyboy 2: The Greg Tate Reader. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. 2016. ISBN 978-0-8223-6180-0.

- Co-editor with Liz Munsell. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the hip-hop generation. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. 2020. ISBN 978-0-8784-6871-3.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Limbong, Andrew (December 7, 2021). "Greg Tate, a powerful chronicler and critic of Black life and culture, has died at 64". NPR. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (May 6, 2024). "Greg Tate Receives Posthumous Pulitzer Prize". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Risen, Clay (December 8, 2021). "Greg Tate, Influential Black Cultural Critic, Dies at 64". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c Hussey, Allison (December 7, 2021). "Greg Tate, Celebrated Hip-Hop Journalist and Cultural Critic, Dies at 64". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Every Show Unique". University of Dayton. July 31, 2006. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Robinson, Amelia (June 15, 2009). "Dayton native gets shoutout in 'Rolling Stone'". Dayton Daily News. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ The Independent Ear (October 30, 2009). "Ain't But a Few of Us: Black Jazz Writers Tell Their Story". Open Sky Jazz. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ a b Infantry, Ashante (March 23, 2008). "Acid Funk Never Sounded Sweeter". Toronto Star. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ a b "Greg Tate (c. 1958–2021)". ArtForum. December 7, 2021. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Shteamer, Hank (December 7, 2021). "Greg Tate, Groundbreaking Cultural Critic and Black Rock Coalition Co-Founder, Has Died". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Greg Tate". Cooper Union. April 12, 2010. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Hsu, Hua (September 21, 2016). "The Critic Who Convinced Me That Criticism Could Be Art". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Tate, Greg (May 25, 2004). "Band in My Head". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Stein, Alex Harris (January 20, 2016). "Tate, Greg(ory Stephen)". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.a2289548. ISBN 9781561592630.

- ^ a b Lordi, Emily (July 26, 2017). "Post-Soul Aesthetics". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Vincent, Rickey (June 25, 2003). "Black Music and Ivory Towers". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Tate, Greg (December 1986). "Cult-Nats Meet Freaky Deke". Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America. New York: Simon & Schuster (published 1992). p. 201. ISBN 0-671-72965-9.

- ^ a b "Greg Tate: Visiting Professor of Africana Studies". Brown University. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ a b Caramanica, Jon (December 8, 2021). "The Peerless Imagination of Greg Tate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Casey, Caroline (October 13, 2009). "Visiting Professor Brings Hip-Hop to Columbia". Columbia Daily Spectator. Archived from the original on December 13, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (December 7, 2021). "Music and cultural critic Greg Tate dead at 64". NBC News. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "Nonfiction Book Review: Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America". Publishers Weekly. May 4, 1992. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (December 7, 2021). "A Warrior for the Heart: The Gigantic Music Legacy of Greg Tate". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Lindsey, Craig (June 1, 2003). "'Everything But the Burden' by Greg Tate". Chron. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Dawes, Laina (September 20, 2005). "Everything but the burden: An interview with author and cultural theo…". AfroToronto. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Battaglia, Andy (July 29, 2003). "Greg Tate: Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix And The Black Experience". The A.V. Club. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ "Greg Tate: Fellow Profile". United States Artists. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Mirakhor, Leah (March 1, 2018). "Fly as Hell: An Interview with Greg Tate". Los Angeles Review of Books. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Caldwell, Noah; Sundaresan, Mano (December 8, 2021). "Revered cultural critic Greg Tate has died at age 64". All Things Considered. NPR. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ Battaglia, Andy (December 7, 2021). "Greg Tate, Influential Critic, Essayist, and Chronicler of the Black Avant-Garde, Dies". ARTnews.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Hunter, J. (January 26, 2012). "Interview: Greg Tate of Burnt Sugar the Arkestra Chamber". Nippertown.

- Clayton Perry, "Interview: Greg Tate – Writer, Musician and Producer", April 8, 2012

External links

[edit]- Articles by Greg Tate Archived June 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine at The Village Voice

- Greg Tate discography at Discogs

- Greg Tate at IMDb

- The Independent Ear, "The Passing of an Ironman", Open Sky Jazz, December 13, 2021.