Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

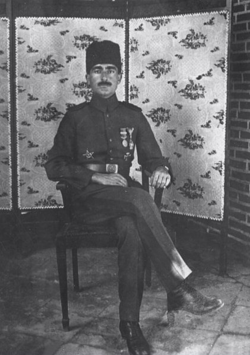

Halil Kut

View on WikipediaHalil Kut (1881 – 20 August 1957),[2] also known as Halil Pasha,[a] was an Ottoman Turkish military commander and politician. He served in the Ottoman Army during World War I, notably taking part in the military campaigns against Russia in the Caucasus and the British in Mesopotamia.

Key Information

Halil was responsible for numerous atrocities committed against Armenian and Assyrian civilians during the Armenian genocide, overseeing the massacres of Armenian men, women and children in Bitlis, Mush, and Beyazit.[3][4][5] Many of the victims were buried alive in specially prepared ditches.[6] He also crossed into neighboring Persia and massacred Armenians, Assyrians and Persians.[7]

Biography

[edit]Halil Pasha graduated from the War Academy (Staff College) in Constantinople in 1905 and received a commission with the rank of Distinguished Captain (Mümtaz Yüzbaşı).[8] His paternal lineage was based on the Gagauz people.[9]

When the Ottoman empire entered World War I, Kut was serving in the Ottoman High Command in Constantinople. He was the military commander of the Istanbul Vilayat between January and December 1914.[10]

In January 1916, he was given command of the Ottoman forces besieging the British garrison held up in Kut in southern Iraq.[11]

Role in Armenian genocide

[edit]Halil Pasha was responsible for massacring Armenians during the course of the Armenian genocide.[3][4][5] He took part in the killings of civilians during the Siege of Van in 1915. He ordered Armenian men in the units under his command be put to death.[12] A Turkish officer in Halil's force testified that "Halil had the entire Armenian population (men, women and children) in the areas of Bitlis, Muş, and Beyazit also massacred without pity. My company received a similar order. Many of the victims were buried alive in especially prepared ditches."[6]

The German vice-consul of Erzurum Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter reported that "Halil Bey's campaign in northern Persia included the massacre of his Armenian and Syrian battalions and the expulsion of the Armenian, Syrian, and Persian population out of Persia ..."[7] After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I he was charged for his role in the Armenian genocide before the Turkish Courts-Martial. Kut was arrested in January 1919 and later sent to detention in Malta.[13] He managed to evade prosecution and fled from detention to Anatolia in August 1920.[14]

Kut went on to claim in his memoirs that he had "more or less" killed 300,000 Armenians.[12] During a meeting with a group of Armenians in Yerevan in the summer of 1918, he declared to that he had "endeavored to wipe out the Armenian nation to the last individual."[12][15] Halil justified his actions by accusing the Armenians of being a threat to the Ottoman Empire. He wrote:

The Armenian nation, because it tried to erase my country from history as prisoners of the enemy in the most horrible and painful days of my homeland, which I had tried to annihilate to the last member of, the Armenian nation, which I want to restore its peace and luxury, because today it takes shelter under the virtue of the Turkish nation. If you remain loyal to the Turkish homeland, I'll do every good thing that I can. If you hook on several senseless Komitadjis again, and try to betray Turks and the Turkish homeland, I will order my forces which surround all your country and I won't leave even a single breathing Armenian all over the earth. Come to your senses.[16]

Kut was permitted to return to Turkey after the declaration of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. He died in 1957 in Istanbul. His last wish was to have rakı (an alcoholic drink) poured on his grave, which became a source of controversy among conservatives in Turkey.[17]

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Biographical note - Khalil Pasha - downloaded from FirstWorldWar.com, January 13, 2006.

- Gaunt, David (2006). Massacres, resistance, protectors: muslim-christian relations in Eastern Anatolia during world war I (1st Gorgias Press ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias. ISBN 1-59333-301-3.[permanent dead link]

- Kiernan, Ben (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500–2000. Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-85477-0.

- Winter, J. M. (2003). America and the Armenian genocide of 1915. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-16382-1.

Notes

[edit]- ^ In this Ottoman Turkish style name, the given name is Halil, the title is Pasha, and there is no family name.

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.soylentidergi.com/kutun-kahramani-halil-pasa/

- ^ "Kutülamara kahramanı Halil Kut dün vefat etti", Milliyet, 21 August 1957.

- ^ a b Morris, B.; Ze'evi, D. (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Harvard University Press. pp. 161–164.

- ^ a b Kiernan, B. (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-300-10098-3.

- ^ a b Winter, J., ed. (2003). America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-0-521-82958-8.

- ^ a b Kiernan 2008, p. 413.

- ^ a b Gaunt 2006, p. 109.

- ^ Simon, Rachel (1987). Libya between Ottomanism and nationalism: the Ottoman involvement in Libya during the War with Italy (1911-1919). K. Schwarz. p. 140. ISBN 978-3-922968-58-0.

- ^ https://macedonia.kroraina.com/en/samo/samo_1_6.htm

- ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N. (1991). "The Documentation of the World War I Armenian Massacres in the Proceedings of the Turkish Military Tribunal". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 23 (4): 559. doi:10.1017/S0020743800023412. S2CID 159478874.

- ^ Eugene Rogan. The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East (New York: Basic Books, 2015), pp. 245-46.

- ^ a b c Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2004-01-08), Winter, Jay (ed.), "The Armenian Genocide: an interpretation", America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915 (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 64–65, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511497605.005, ISBN 978-0-521-82958-8, retrieved 2023-04-11

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N.; Akçam, Taner (2011). Judgment at Istanbul: The Armenian Genocide Trials. Berghahn Books. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-85745-251-1.

- ^ Kévorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 794.

- ^ Gaunt 2006, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Halil Pasha, Bitmeyen Savaş, pp. 240–41. The original text reads: "Vatanımın en korkunç ve acı günlerinde vatanımı düşmana esir olarak tarihten silmeye kalktıkları için son ferdine kadar yok etmeye çalıştığım Ermeni Milleti, bugün Türk milletinin âlicenaplığına sığındığı için huzura ve rahata kavuşturmak istediğim Ermeni milleti. Eğer siz Türk vatanına sâdık kalırsanız elimden gelen her iyi şeyi yapacağım. Eğer yine bir takım şuursuz komitacılara takılarak Türk'e ve Türk vatanına ihanete kalkarsanız bütün memleketinizi saran ordularıma emir vererek dünya üstünde nefes alacak tek Ermeni bırakmayacağım, aklınızı başınıza alın."

- ^ Kut'ül Amare komutanı: Mezarıma rakı dökün

Halil Kut

View on GrokipediaHalil Kut Pasha (1881–1957) was an Ottoman military commander, notable for his leadership in the Mesopotamia campaign during World War I, where he orchestrated the siege and capture of British forces at Kut al-Amara.[1]

Born in Constantinople to a family connected to Ottoman elites, Kut graduated from the War Academy in 1905 and rose through the ranks amid the Young Turk Revolution, serving as commander of the Imperial Guard and participating in the Italo-Turkish War and Balkan Wars.[1][2] As uncle to War Minister Enver Pasha and a member of the Committee of Union and Progress, he was appointed to key positions, including military governor of Constantinople in 1914.[1] In late 1915, Kut assumed command of Ottoman forces in Mesopotamia, replacing Nureddin Pasha; his strategic encirclement and blockade led to the surrender of 13,309 British and Indian troops on 29 April 1916 after a five-month siege, a rare Ottoman triumph that boosted morale and earned him promotion to major general and the title of pasha.[1] Despite this success, subsequent operations under his command, including the defense of Baghdad, ended in retreat and loss to advancing British forces in March 1917.[1] Later redeployed to the Caucasus, he contributed to the Ottoman advance on Baku in 1918.[1] Postwar, Kut faced Allied arrest in 1919 for alleged complicity in the massacres of Armenians and Assyrians during deportations in Mesopotamia, charges linked to Special Organization units under his oversight that reportedly executed thousands; though indicted for crimes against humanity, he escaped Malta exile in 1920, mediated in the Turkish War of Independence, and returned to Turkey in 1923 without facing trial.[1][3] He died in Istanbul on 20 August 1957.[1]

Early Life and Education

Family Background and Upbringing

Halil Kut was born in 1881 in Constantinople, within the Ottoman Empire. He was the paternal uncle of İsmail Enver Pasha, who later became the Ottoman Minister of War, despite Halil being only one year younger than Enver, born in late 1881. This close familial tie integrated him into the networks of Ottoman military and reformist elites associated with the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).[1][2] From an early age, Kut's upbringing oriented toward military service, reflecting the Ottoman tradition of grooming promising youth from officer families for leadership roles. He entered the Ottoman military education system and graduated from the War Academy in 1905, marking the completion of his formal training.[1][2] Following graduation, Kut's initial postings with the Third Army in Macedonia from 1905 to 1908 exposed him to the ethnic tensions and administrative challenges of the Balkan provinces, further shaping his career trajectory amid the empire's pre-war reforms and insurgencies. His early involvement with the CUP underscored the political dimensions of his family-influenced upbringing.[1]

Military Training and Early Influences

Halil Kut underwent formal military training at the Ottoman Imperial Military Academy (Harbiye Mektebi) in Istanbul, graduating in 1905 as a staff officer.[1] This education emphasized modern infantry tactics, strategy, and administration, aligning with the Ottoman Empire's efforts to reform its army under German advisory influence following the 1908 Young Turk Revolution.[1] Following graduation, Kut was assigned to the Third Army in Macedonia, serving there from 1905 to 1908, a region rife with ethnic tensions and revolutionary fervor that exposed him to irregular warfare and political intrigue.[1] During this posting, he joined the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the dominant reformist and nationalist organization driving the empire's modernization, which profoundly shaped his ideological outlook toward centralized authority and anti-imperialist resistance.[1] In 1908, at CUP direction, he was dispatched to Persia to organize dissident forces against Shah Mohammad Ali, honing skills in covert operations and tribal mobilization.[1] Kut's rapid early advancement reflected both merit and nepotism, as he was the uncle of İsmail Enver Pasha, a rising CUP leader and his junior by one year, fostering access to elite networks.[1] After suppressing the 1909 counter-revolutionary uprising in Istanbul, he commanded the Imperial Guard and mobile gendarmerie units in Salonica, roles that involved internal security and loyalty enforcement amid factional strife.[1] Pre-World War I combat experience came via the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912) in Tripoli, where he led units against Italian invaders, and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), exposing him to defensive attrition and alliance betrayals that reinforced CUP emphases on military self-reliance.[1] By war's eve, he headed a gendarmerie regiment in Van, blending administrative duties with frontier defense against Armenian unrest.[1]Pre-World War I Career

Balkan Wars Participation

During the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, Halil Kut served as a commander of a military unit in the Ottoman Army, marking one of his early instances of active combat duty.[1] At approximately 30 years old and holding the rank of major following his 1905 graduation from the Ottoman War Academy, Kut participated amid the Ottoman Empire's rapid territorial losses in Europe during the First Balkan War, where allied forces of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro overran positions in Thrace and Macedonia, culminating in the siege and fall of Edirne on 26 March 1913.[1] Specific details of his unit's engagements, such as precise battles or tactical contributions, are sparsely documented, reflecting his relatively junior status and the broader chaos of Ottoman defeats that displaced over 400,000 Muslim refugees and reduced European holdings to a sliver of Thrace.[4] In the Second Balkan War, triggered by Bulgaria's disputes with its allies on 29 June 1913, Ottoman forces exploited the fragmentation to launch a counteroffensive, recapturing Edirne by 21 July 1913 under the command of Shukri Pasha.[4] Kut's military unit likely supported these operations in Thrace, though primary accounts do not attribute standout actions to him individually, consistent with the decentralized and often improvised nature of Ottoman field commands during the conflict.[1] The wars exposed systemic Ottoman military weaknesses, including logistical failures and mobilization issues that mobilized around 1.2 million troops yet yielded disproportionate casualties exceeding 200,000, setting the stage for internal reforms and Kut's subsequent intelligence and administrative roles before World War I.[4]Administrative and Intelligence Roles

Prior to the Italo-Turkish War, Halil Kut's roles emphasized internal security and covert operations aligned with the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the revolutionary organization he joined while serving in the Ottoman Third Army in Macedonia from 1905 to 1908.[1] In 1908, the CUP dispatched Kut to Persia to incite insurrection against Shah Mohammad Ali Qajar, a clandestine assignment that demonstrated his early engagement in intelligence and subversive activities on behalf of Ottoman interests.[1] Returning in 1909, Kut assumed command of the Imperial Guard, an elite administrative and protective force under the sultan's direct authority, before transitioning to lead mobile gendarmerie units in Salonica; these positions involved coordinating law enforcement, suppressing unrest, and maintaining order in a volatile European province prone to ethnic tensions.[1] By the early 1910s, Kut held the post of chief of a gendarmerie regiment in Van province in eastern Anatolia, where his duties centered on administrative management of provincial security forces and active pursuit of armed bands, including Kurdish and Armenian insurgents, requiring intelligence assessment of threats to Ottoman control in a frontier region.[1]World War I Service

Mesopotamian Front and Kut al-Amara Victory

Halil Pasha, appointed commander of the Ottoman Sixth Army's Tigris Group following the dismissal of Nurettin Pasha amid heavy casualties in late 1915, assumed responsibility for the ongoing siege of Kut al-Amara in early 1916.[5] The British-Indian force under Major General Charles Townshend, numbering approximately 11,600 combatants and 3,350 non-combatants, had retreated into the town on December 3, 1915, after Ottoman counterattacks halted their advance up the Tigris River.[6] Ottoman forces, initially under Nurettin and later reinforced under Halil's direction, encircled the position on December 7, 1915, initiating a 147-day blockade.[7] Under Halil Pasha's leadership, Ottoman troops repelled multiple British relief expeditions, including the failed attempts at the Battle of Wadi on January 13, 1916, and subsequent operations that inflicted heavy losses on the relief column led by Lieutenant General Sir Fenton Aylmer.[8] [6] Besieged troops endured severe shortages of food and supplies, exacerbated by failed aerial resupply drops and riverine efforts, leading to widespread starvation and disease by spring 1916. Halil rejected British offers of ransom for the garrison, insisting on unconditional surrender as directed by War Minister Enver Pasha.[9] On April 29, 1916, Townshend capitulated, with 13,000 British and Indian soldiers surrendering—the largest such capitulation by British forces until World War II.[7] [10] The victory, achieved despite Ottoman casualties estimated at 24,000 during the broader Kut operations, boosted morale across the empire and temporarily halted British advances in Mesopotamia.[6] Halil Pasha received the Ottoman Gold Medal of Distinguished Service for his role in securing the triumph.[11] This success underscored effective Ottoman defensive tactics and exploitation of terrain and logistics against a numerically inferior but initially aggressive foe.[12]Caucasus Campaign and Baku Expedition

In the wake of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918, which ended Russian participation in World War I, Ottoman forces initiated a renewed offensive in the Caucasus to reclaim territories lost during earlier campaigns. Halil Pasha, drawing on his prior successes in Mesopotamia, assumed command of Ottoman units in the eastern theater, including elements of the 6th Army, which provided intelligence and operational support for advances into Transcaucasia. These efforts focused on securing Muslim-majority regions and countering Bolshevik and Armenian irregulars amid the collapse of Russian authority.[13] On 29 June 1918, Halil Pasha was appointed commander of the Eastern Army Group, replacing Vehip Pasha, with oversight of the Third Army and the newly formed Army of Islam under Nuri Pasha. This group, comprising approximately 15,000 Ottoman troops augmented by Azerbaijani militias, aimed to capture Baku to control vital oil resources and establish Ottoman influence in the Caspian region. Halil's command coordinated logistics and reinforcements from eastern Anatolia, enabling the Army of Islam to defeat opposing forces—primarily Bolsheviks supported by Armenian units and a small British Dunsterforce—at the Battle of Goychay from 27 June to 1 July 1918, where Ottoman artillery and infantry overwhelmed disorganized defenders, resulting in over 2,000 enemy casualties.[13][14] The subsequent siege of Baku commenced in early August 1918, with Ottoman forces encircling the city defended by around 6,000-9,000 troops under the Baku Commune. Halil Pasha's group pressured supply lines from the north and east, while Nuri Pasha's field units conducted assaults amid harsh terrain and limited munitions. On 15 September 1918, after the defenders evacuated under British urging, Ottoman-Azerbaijani troops entered Baku unopposed, securing the city and its oil fields without a final pitched battle. Halil Pasha reported witnessing extensive prior atrocities, including Armenian and Bolshevik tortures of Muslim civilians, followed by retaliatory violence; Armenian National Council records, cited in his accounts, documented 8,988 Armenian deaths in the ensuing unrest. Ottoman authorities under his direction imposed martial law on 16 September, executing over 100 individuals for looting and killings to restore order.[15][13][14]Eastern Anatolia Operations

Security Measures Amid Armenian Rebellions

In early 1915, as the Ottoman Third Army faced setbacks in the Caucasus, Armenian revolutionary groups in eastern Anatolia, including committees affiliated with the Dashnaktsutyun party, initiated armed uprisings that threatened Ottoman control over rear areas and supply lines.[16] These actions, coordinated with advancing Russian forces, included the seizure of Van on April 20, 1915, by approximately 1,500 Armenian fighters who killed Ottoman officials and an estimated 8,000 Muslim civilians.[17] Halil Kut, serving as a divisional commander in the Third Army, was involved in the military response to these security threats.[1] Security measures under Halil's command emphasized rapid suppression of rebel strongholds through combined regular army units and local irregular forces, such as Kurdish tribal militias, to prevent further collaboration with the enemy.[1] In June 1915, the Fifth Expeditionary Corps, operating in the Siirt district of Bitlis Province amid local Armenian resistance, conducted operations that resulted in the deaths of thousands of Armenians and about 5,000 Assyrians or Chaldeans.[1] Similarly, in July 1915, Halil ordered actions in the Muş district targeting Armenian villages, leading to the reported massacre of 75,000 inhabitants, with men executed and women and children subjected to mass burnings.[1] These operations aimed to neutralize armed groups but extended to civilian populations suspected of supporting the rebellions. Halil's approach reflected the Ottoman high command's prioritization of rear security during wartime, viewing Armenian communities as potential fifth columns due to prior revolutionary activities and Russian incitement.[18] In his post-war memoirs, he claimed personal responsibility for the elimination of 300,000 Armenians as a necessary measure against existential threats to the empire.[1] Post-war Ottoman court-martials charged him with complicity in atrocities against Armenians, though he evaded prosecution by fleeing in August 1920.[1] Turkish historical accounts frame these actions as defensive countermeasures against documented uprisings, contrasting with international characterizations of systematic extermination.[16]Deportations and Population Relocations

Halil Kut's involvement in population relocations in Eastern Anatolia stemmed from his military commands and brief leadership of the Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization), a paramilitary unit tasked with irregular operations, including suppressing rebellions and managing displaced groups amid World War I. Appointed director of the organization in November 1914, Kut oversaw early activities in eastern provinces where Armenian nationalist groups had launched uprisings, such as the Van revolt in April 1915, which coincided with Russian advances and resulted in the deaths of Ottoman soldiers and Muslim civilians. The Special Organization assisted in enforcing the Ottoman government's Temporary Law of Deportation (Tehcir Kanunu), enacted on May 27, 1915, which authorized the relocation of Armenians from frontline areas to southern provinces like Syria and Mesopotamia to neutralize perceived security threats from potential fifth-column activities.[19][20] Following his victory at Kut al-Amara in April 1916, Kut was redeployed to eastern commands, including Bitlis province, where he directed operations during the Russian retreat in mid-1916. These efforts involved relocating remaining Armenian populations suspected of collaboration with occupying forces, as well as resettling Muslim refugees fleeing Russian incursions in the Caucasus. In Bitlis and adjacent areas like Muş and Beyazıt, deportation convoys under Ottoman and tribal escorts faced ambushes, disease, and exposure, leading to high mortality; Armenian accounts report massacres of thousands by local Kurds mobilized for security, while Ottoman military correspondence attributes losses to wartime chaos, banditry, and retaliatory actions against documented Armenian attacks on Muslim villages. Kut's forces reportedly neutralized resistance in these regions, with one Ottoman officer's memoir describing the execution of armed Armenian groups "without pity" to restore order.[21][22] The relocations displaced an estimated 300,000-400,000 Armenians from eastern vilayets by late 1916, with vacated lands allocated to Muslim refugees from Russia and the Balkans, reflecting a broader Ottoman strategy of demographic reconfiguration for loyalty and defense. Halil Kut maintained in post-war statements that these measures prevented further insurgencies, citing intelligence on Armenian-Russian pacts and prior massacres of 100,000+ Muslims in the region since 1914. Accusations of systematic extermination leveled against him in Allied-inspired trials were dismissed in Ottoman court-martials as distortions by biased witnesses, often Armenian nationalists; Turkish historiography emphasizes the relocations' provisional nature and parallels to Allied population transfers, critiquing Western and academic sources for overlooking empirical evidence of mutual wartime violence and systemic anti-Ottoman bias in post-war tribunals.[23][24]Controversies and Legal Proceedings

Accusations of Atrocities

Halil Kut, as commander of Ottoman forces in Eastern Anatolia from January 1916, was accused of directing massacres of Armenian civilians during the implementation of deportation orders, with claims that his units systematically killed deportees rather than merely relocating them for security reasons. Indictments in the post-war Ottoman military tribunals, convened under international pressure in 1919, charged him with the "crime of massacres" (taktil cinayeti) for atrocities in provinces under his authority, including Bitlis and Muş, where prosecutors alleged coordinated killings of Armenian populations amid reported rebellions.[23] These proceedings cited witness testimonies and telegrams purportedly ordering excessive violence beyond wartime exigencies.[25] In the Caucasus Campaign of 1918, Kut commanded the Ottoman Army of Islam during the capture of Baku on September 15, after which Ottoman and Azerbaijani forces were implicated in reprisal killings targeting Armenian residents, resulting in an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 deaths over the following week. Accusers, including Armenian survivors and contemporary observers, attributed direct responsibility to Kut for inciting or failing to curb the violence, pointing to his pre-offensive statements threatening annihilation of Armenians in the region as evidence of intent.[25] Similar charges extended to Assyrian (Syriac) communities in Hakkari and Urmia areas, where his forces were said to have conducted punitive expeditions involving village burnings and executions in 1915–1916, framed by critics as ethnic cleansing rather than counterinsurgency.[19] Western Allied powers, in compiling lists of suspected Ottoman war criminals for potential trials, included Kut for "crimes against humanity" linked to these events, a novel legal category invoked in 1919 correspondence among British, French, and American officials reviewing deportation-related deaths estimated in the hundreds of thousands across the empire.[26] These accusations drew from consular reports, missionary accounts, and survivor narratives, though Ottoman defenders countered that documented Armenian insurgencies—such as arms seizures and uprisings in Van and Bitlis—justified relocations and reprisals to prevent rear-guard sabotage.[25] No convictions resulted from Allied efforts, as Kut evaded extradition during the Turkish War of Independence.Ottoman Court-Martial and Turkish Perspectives

Following the Armistice of Mudros on October 30, 1918, the Ottoman government in Istanbul, led by Grand Vizier Damad Ferid Pasha and under Allied occupation influence, established special military tribunals in 1919 to prosecute former Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) officials for wartime actions, including the 1915 Armenian deportations. Halil Kut, as commander of the Third Army in eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus from 1915 onward, faced charges of complicity in organizing mass deportations and associated civilian deaths, with tribunal indictments citing his telegrams authorizing relocations from provinces like Van and Bitlis amid reported Armenian uprisings.[27] These proceedings referenced his oversight of irregular units linked to the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization), alleging systematic excesses beyond security needs. Halil Kut departed Istanbul in early 1919 before a verdict, joining Mustafa Kemal's nationalist movement in Anatolia and evading formal judgment, as the tribunals convicted several CUP leaders in absentia but saw limited enforcement amid political instability.[28] Turkish historical accounts dismiss the Istanbul tribunals as coerced show trials orchestrated by British and Allied authorities to impose the Treaty of Sèvres and undermine Ottoman sovereignty, lacking impartiality and relying on coerced testimonies or fabricated evidence.[29] From this perspective, Halil Kut's directives for population relocations were pragmatic responses to documented Armenian revolutionary activities—such as the Van uprising in April-May 1915, coordinated with Russian advances and involving arms caches uncovered in Armenian communities—aimed at securing rear lines during existential threats from Russia and internal sabotage. Casualties during marches are attributed primarily to wartime hardships, disease epidemics (e.g., typhus outbreaks affecting all populations), banditry, and localized unauthorized killings by rogue elements, rather than centralized extermination policy; Armenian sources amplifying massacre claims are viewed as exaggerated by diaspora narratives seeking reparations or territorial gains, often ignoring Ottoman records of provisioning convoys and relief efforts hampered by logistical collapse. Halil's acquittal in absentia by the Turkish Grand National Assembly's 1926 amnesty for nationalist fugitives reinforced this framing, nullifying prior verdicts as invalid under the new republic. In contemporary Turkish historiography and public memory, Halil Kut—known as "Kut'ül Amare Fatihi" (Conqueror of Kut al-Amara)—embodies martial prowess and patriotic defiance, credited with the April 29, 1916, siege victory capturing 13,000 British troops and boosting Ottoman morale amid broader defeats.[6] His Eastern operations are recast as integral to national survival against a multi-front war, with deportation orders (e.g., Tehcir Law of May 27, 1915) justified by empirical threats like Armenian legion formations aiding Russian invasions, evidenced by captured documents and POW interrogations. Critics of atrocity accusations highlight inconsistencies in Allied-era reports, influenced by wartime propaganda, and note Halil's post-war role as a Grand National Assembly deputy (1923-1927), underscoring rehabilitation as a defender of the homeland rather than perpetrator.[30] This view prioritizes causal chains of rebellion provoking relocation over intent-based genocide claims, emphasizing that similar internment policies occurred globally during World War I without equivalent condemnation.Post-War Life

Involvement in Turkish Independence

Following his arrest by British authorities in January 1919 and subsequent exile to Malta on charges related to wartime actions in the Caucasus, Halil Kut escaped detention in August 1920 and traveled to Moscow.[31] There, he acted as an intermediary between Soviet Bolshevik leaders and the Turkish National Movement led by Mustafa Kemal, facilitating early diplomatic and material support crucial to the nationalists' resistance against Allied occupation forces and Greek advances in Anatolia.[31] In a key operation, Kut personally delivered a shipment of gold bullion provided by Vladimir Lenin to Kemal's representatives, intended to secure the return of the Batum region from Soviet control to Turkish hands as part of broader negotiations amid the independence struggle.[31] He further arbitrated disputes between Bolshevik interests and Kemalist forces, helping to align Soviet aid— including arms, financial resources, and recognition—with the Turkish nationalists' military campaigns from 1920 to 1922, which proved instrumental in sustaining operations against superior enemy numbers.[31] This behind-the-scenes role underscored Kut's alignment with the independence movement despite his prior Ottoman affiliations and Enver Pasha's rival pan-Turkic activities in Central Asia. Kut visited Germany in 1922 to gauge European sentiments toward the Turkish cause before returning to Turkey in 1923, shortly after the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey and the Treaty of Lausanne, which formalized independence.[31] His contributions, though non-combatant, bolstered the movement's logistical resilience during its most precarious phases, reflecting a pragmatic shift from Ottoman loyalism to support for the emerging republican framework.[31]Later Years and Death

Following his return to Turkey in 1923 after the proclamation of the Republic, Halil Kut retired from public life and resided in Istanbul without further military or political involvement.[1][2] He lived quietly for the remaining decades, having been granted special permission to re-enter the country after years of exile and movement through the Soviet Union and Germany.[2] Kut died in Istanbul on August 20, 1957, at the age of 76.[1]Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Military Accomplishments

Halil Kut, known as Halil Pasha, emerged as a key Ottoman commander during World War I, commanding forces in Mesopotamia and the Caucasus regions with notable successes against numerically superior Allied armies. Graduating from the Ottoman War Academy in 1905, he held staff positions before the war and was assigned to the Third Army in the Caucasus upon Ottoman entry into the conflict in November 1914. [2] [1] In April 1915, Halil commanded the 1st Expeditionary Force advancing into northern Persia to counter Russian advances and suppress the Armenian rebellion in the Van region, capturing the city of Dilman after initial setbacks against Russian forces. [1] [32] This operation aimed to secure Ottoman flanks amid the broader Caucasus Campaign, where Halil served as a divisional commander, contributing to defensive efforts despite the Third Army's overall strains. [1] Transferred to Mesopotamia in late 1915, Halil replaced Nureddin Bey as commander of the Tigris Corps within the Sixth Army, assuming responsibility for besieging the British-Indian garrison at Kut al-Amara on 8 December 1915. [5] Under his leadership, Ottoman forces withstood harsh conditions and repelled multiple British relief expeditions, including the failed advance under General Aylmer, which suffered over 23,000 casualties. [6] The 147-day siege culminated on 29 April 1916 with the surrender of Major General Charles Townshend's force of 13,309 troops, including nine generals, marking one of the Ottoman Empire's most decisive victories of the war and yielding 13,000 prisoners alongside significant materiel. [8] [1] In early 1917, Halil redeployed elements of his command to Persia to disrupt British-backed governance and support Ottoman strategic aims, conducting raids that temporarily destabilized the region before Allied reinforcements shifted the balance. [1] These campaigns, executed with limited resources, demonstrated Halil's tactical acumen in mobile warfare and siege operations, earning him promotion to pasha and medals for valor, though Ottoman casualties across his commands exceeded 24,000 in Mesopotamia alone. [6] His achievements bolstered Ottoman morale amid broader wartime setbacks, highlighting effective leadership in peripheral fronts. [33]