Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Baghdad

View on Wikipedia

This article contains too many images for its overall length. |

Baghdad[a] is the capital and largest city in Iraq. It is located on the banks of the Tigris in central Iraq. The city has an estimated population of 8 million and span across 673 square kilometres (260 sq mi) of area. It ranks among the most populous and largest cities in the Middle East and the Arab world and constitutes 22% of the country's population. Baghdad is a primary financial and commercial center in the region.

Key Information

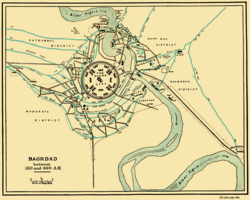

Founded in 762 AD by Al-Mansur, Baghdad was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate and became its most notable development project. The city evolved into an intellectual and cultural center. This, in addition to housing several key academic institutions, including the House of Wisdom, as well as a multi-ethnic and multi-religious environment, garnered it a worldwide reputation as the "Center of Learning". For much of the Abbasid era, during the Islamic Golden Age, Baghdad was one of the largest cities in the world and rivaled Chang'an, as the population peaked at more than one million. It was largely destroyed at the hands of the Mongol Empire in 1258, resulting in a decline that would linger through many centuries due to frequent plagues, shift in power and multiple successive empires. Later, Baghdad served as the administrative center of Ottoman Iraq,[3] exercising authority over the provinces of Basra, Mosul, and Shahrizor.[4] '

During First World War, Baghdad was made the capital of Mandatory Iraq. With the recognition of Iraq as an independent monarchy in 1932, it gradually regained some of its former prominence as a significant center of Arab culture. During the Ba'ath Party rule, the city experienced a period of relative prosperity and growth. However, it faced severe infrastructural damage due to the Iraq War, which began with the invasion of Iraq in 2003, resulting in a substantial loss of cultural heritage and historical artifacts. During the insurgency and renewed war from 2013 to 2017, it had one of the highest rates of terrorist attacks in the world. However, these attacks have gradually declined since the territorial defeat of the Islamic State militant group in Iraq in 2017, and are now rare. Since the end of the war, numerous reconstruction projects have been underway to induce stability.

Iraq's largest city, Baghdad is the seat of government. It generates 40% of the economy of Iraq. A major center of Islamic history, Baghdad is home to numerous historic mosques, as well as churches, mandis and synagogues, highlighting the city's historical diversity. Religious sites such as Masjid al-Kadhimayn, Buratha Mosque, the Shrine of Abdul-Qadir Gilani and Abu Hanifa Mosque are visited by millions of people annually. It was once home to a large Jewish community and was regularly visited by Sikh pilgrims from India.[5] Baghdad is a regional cultural hub. The city is well known for its coffeehouses.

Name

[edit]The name Baghdad is pre-Islamic, and its origin is disputed.[6] The site where the city of Baghdad developed has been populated for millennia. Archaeological evidence shows that the site of Baghdad was occupied by various peoples long before the Arab conquest of Mesopotamia in 637 CE, and several ancient empires had capitals located in the surrounding area.[7]

Arab authors, realizing the pre-Islamic origins of Baghdad's name, generally looked for its roots in Middle Persian.[6] They suggested various meanings, the most common of which was "bestowed by God".[6][8] Modern scholars generally tend to favor this etymology,[6] which views the word as a Persian compound of bagh (![]() ) "god" and dād (

) "god" and dād (![]() ) "given".[9][10] In Old Persian the first element can be traced to boghu and is related to Indo-Iranian bhag and Slavic bog "god."[6][11] A similar term in Middle Persian is the name Mithradāt (Mehrdad in New Persian), known in English by its borrowed Hellenistic form Mithridates, meaning "Given by Mithra" (dāt is the more archaic form of dād, related to Sanskrit dāt, Latin dat and English donor),[6] ultimately borrowed from Persian Mehrdad. There are a number of other locations whose names are compounds of the Middle Persian word bagh, including Baghlan and Bagram in Afghanistan, Baghshan in Iran itself,[12] and Baghdati in Georgia, which likely share the same etymological Iranic origins.[13][14][15]

) "given".[9][10] In Old Persian the first element can be traced to boghu and is related to Indo-Iranian bhag and Slavic bog "god."[6][11] A similar term in Middle Persian is the name Mithradāt (Mehrdad in New Persian), known in English by its borrowed Hellenistic form Mithridates, meaning "Given by Mithra" (dāt is the more archaic form of dād, related to Sanskrit dāt, Latin dat and English donor),[6] ultimately borrowed from Persian Mehrdad. There are a number of other locations whose names are compounds of the Middle Persian word bagh, including Baghlan and Bagram in Afghanistan, Baghshan in Iran itself,[12] and Baghdati in Georgia, which likely share the same etymological Iranic origins.[13][14][15]

Other authors have suggested older origins for the name, in particular the name Bagdadu or Hudadu that existed in Old Babylonian (spelled with a sign that can represent both bag and hu), and the Jewish Babylonian Aramaic name of a place called Baghdatha (בגדתא).[6][16][17] Some scholars suggested Aramaic derivations.[6]

Another highly recommended view is that Baghdad is a reference to Bagh and Dad as in Dadan, Dedan, and Dad as in Hadad, Adad. Another view suggested by Christophe Wall-Romana, is that name of "Baghdad" is derived from "Akkad", as the cuneiform logogram for Akkad (𒀀𒂵𒉈𒆠) is pronounced "a-ga-dèKI" ("Agade") and its resemblance to "Baghdad" is compelling.[18][19] It is argued that, throughout all the various spellings of the city's name, whether Baghdad [بغداد], Baghdadh [بغداذ], Baghdan [بغدان], Maghdad [مغداد], Maghdadh [مغداذ], or Maghdan [مغدان], the only phonetically definite segment of the name appears to be Aghda [ىَغْدَا], which could be equated with the pronunciation of the name Agade.[19][20]

When the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur founded a completely new city for his capital, he chose the name "City of peace" (Arabic: مدینة السلام, romanized: Madīnat as-Salām), which now refers to the Round City of Baghdad proper. By the 11th century, Baghdad became almost the exclusive name for the world-renowned metropolis.

Christophe Wall-Romana has suggested that al-Mansur's choice to found his "new city" at Baghdad because of its strategic location was the same criteria which influenced Sargon's choice to found the original city of Akkad in the exact same location.[21][22]

History

[edit]Foundation

[edit]

After the fall of the Umayyads, the victorious Abbasids sought a new capital.[23][24] On 30 July 762, the Caliph Al-Mansur commissioned Baghdad's construction, guided by the Iranian Barmakids. He believed Baghdad was ideal for ruling the Islamic Empire. Historian al-Tabari recorded a prophecy from Christian monks about a leader named Miklas building a great city in the area, and Al-Mansur, who was once called Miklas, saw this as a good omen. He expressed deep affection for the site, declaring it would be the home of his dynasty.[23][24][25][26]

The two designers who were hired by Al-Mansur to plan the city's design were Naubakht, a Zoroastrian who also determined that the date of the foundation of the city would be astrologically auspicious, and Mashallah, a Jew from Khorasan, Iran.[27][28][29] They determined the city's auspicious founding date under the sign of Leo the lion, symbolizing strength and expansion.[30]

Baghdad's strategic location along the Tigris and its abundant water supply contributed to its rapid growth. It was divided into three judicial districts: Round City (Madinat al-Mansur), al-Karkh (al-Sharqiyya), and Askar al-Mahdi. To prevent disturbances, Al-Mansur moved markets to al-Karkh. Over time, Baghdad became a hub for merchants and craftsmen. Officials called "Muhtasib" monitored trade to prevent fraud.[31][32]

Baghdad surpassed Ctesiphon, the former Sassanid capital, located 30 km southeast. The ruins of Ctesiphon remain in Salman Pak, where Salman the Persian is believed to be buried.[33] Ctesiphon itself had replaced Seleucia, which had earlier succeeded Babylon.[34][35] According to the traveler Ibn Battuta, Baghdad was one of the largest cities,[36] not including the damage it has received. The residents are mostly Hanbalis.[37] Most residents were Hanbali Muslims. The city housed Abu Hanifa's grave, marked by a mosque and cell.[38] Its ruler, Abu Said Bahadur Khan, was a Tatar who had embraced Islam.[39]

Baghdad was designed to symbolize Paradise as described in the Qur'an.[40] It took four years (764–768) to build, with over 100,000 workers involved. Al-Mansur recruited engineers and artisans worldwide. Astrologers Naubakht Ahvazi and Mashallah advised starting construction under Leo, associated with fire, productivity, and expansion. Bricks for the city were 18 inches square, and Abu Hanifah supervised their production. A canal supplied water for drinking and construction. Marble was used extensively, including steps leading to the river.[41][42][30][43][44]

The city's layout consisted of two large semicircles, with a 2 km-wide circular core known as the "Round City." It had parks, gardens, villas, and promenades. Unlike European cities of the time, Baghdad had a sanitation system, fountains, and public baths, with thousands of hammams enhancing hygiene. The mosque and guard headquarters stood at the center, though some central space's function remains unknown. Baghdad's circular design reflected ancient Near Eastern urban planning, similar to the Sasanian city of Gur and older Mesopotamian cities like Mari.[43][45][46] While Tell Chuera and Tell al-Rawda also provide examples of this type of urban planning existing in Bronze Age Syria.[47][48] This style of urban planning contrasted with Ancient Greek and Roman urban planning, in which cities are designed as squares or rectangles with streets intersecting each other at right angles.

Baghdad was lively, with attractions like cabarets, chess halls, live plays, concerts, and acrobatics.[49] Storytelling flourished, with professional storytellers (al-Qaskhun) captivating crowds, inspiring the tales of Arabian Nights.[50] The city had four walls named after major destinations—Kufa, Basra, Khurasan, and Syria; their gates pointed in on these destinations.[51] The gates were 2.4 km apart, with massive iron doors requiring several men to operate.[52] The walls, up to 44 meters thick and 30 meters high, were reinforced with a second wall, towers, and a moat for added defense.[53] On street corners, storytellers engaged crowds with tales such as those later told in Arabian Nights.[46][54] The Golden Gate Palace, home of the caliph, stood at Baghdad's center with a grand 48-meter green dome. Only the caliph could approach its esplanade on horseback. Nearby were officer residences and a guardhouse. After Caliph Al-Amin's death in 813, the palace ceased to be the caliph's residence.

Center of learning (8th–9th centuries)

[edit]Within a generation of its founding, Baghdad became a hub of learning and commerce. The city flourished into an unrivaled intellectual center of science, medicine, philosophy, and education, especially with the Abbasid translation movement began under the second caliph Al-Mansur and thrived under the seventh caliph Al-Ma'mun.[55] Baytul-Hikmah or the "House of Wisdom" was among the most well known academies,[56] and had the largest selection of books in the world by the middle of the 9th century.[citation needed] Notable scholars based in Baghdad during this time include translator Hunayn ibn Ishaq, mathematician al-Khwarizmi, and philosopher Al-Kindi.[56]

Although Arabic was used as the language of science, the scholarship involved not only Arabs, but also Persians, Syriacs,[58] Nestorians, Jews, Arab Christians,[59][60] and people from other ethnic and religious groups native to the region.[61][62][63][64] These are considered among the fundamental elements that contributed to the flourishing of scholarship in the Medieval Islamic world.[65][66][67] Baghdad was also a significant center of Islamic religious learning, with Al-Jahiz contributing to the formation of Mu'tazili theology, as well as Al-Tabari culminating in the scholarship on the Quranic exegesis.[55] Baghdad is likely to have been the largest city in the world from shortly after its foundation until the 930s, when it tied with Córdoba.[68] Several estimates suggest that the city contained over a million inhabitants at its peak.[69] Many of the One Thousand and One Nights tales, widely known as the Arabian Nights, are set in Baghdad during this period. It would surpass even Constantinople in prosperity and size.[70] Among the notable features of Baghdad during this period were its exceptional libraries. Many of the Abbasid caliphs were patrons of learning and enjoyed collecting both ancient and contemporary literature. Although some of the princes of the previous Umayyad dynasty had begun to gather and translate Greek scientific literature, the Abbasids were the first to foster Greek learning on a large scale. Many of these libraries were private collections intended only for the use of the owners and their immediate friends, but the libraries of the caliphs and other officials soon took on a public or a semi-public character.[71]

Four great libraries were established in Baghdad during this period. The earliest was that of the famous Al-Ma'mun, who was caliph from 813 to 833. Another was established by Sabur ibn Ardashir in 991 or 993 for the literary men and scholars who frequented his academy.[71] This second library was plundered and burned by the Seljuks only seventy years after it was established. This was a good example of the sort of library built up out of the needs and interests of a literary society.[71] The last two were examples of madrasa or theological college libraries. The Nezamiyeh was founded by the Persian Nizam al-Mulk, who was vizier of two early Seljuk sultans.[71] It continued to operate even after the coming of the Mongols in 1258. The Mustansiriyya Madrasa, which owned an exceedingly rich library, was founded by Al-Mustansir, the second last Abbasid caliph, who died in 1242.[71] This would prove to be the last great library built by the caliphs of Baghdad.

Stagnation and invasions (10th–16th centuries)

[edit]

By the 10th century, the city's population was between 1.2 million[72] and 2 million.[73] Baghdad's early meteoric growth eventually slowed due to troubles within the Caliphate, including relocations of the capital to Samarra (during 808–819 and 836–892), the loss of the western and easternmost provinces, and periods of political domination by the Iranian Buwayhids (945–1055) and Seljuk Turks (1055–1135). The Seljuks were a clan of the Oghuz Turks from Central Asia that converted to the Sunni branch of Islam. In 1040, they destroyed the Ghaznavids, taking over their land and in 1055, Tughril Beg, the leader of the Seljuks, took over Baghdad. The Seljuks expelled the Buyid dynasty of Shiites that had ruled for some time and took over power and control of Baghdad. They ruled as Sultans in the name of the Abbasid caliphs (they saw themselves as being part of the Abbasid regime). Tughril Beg saw himself as the protector of the Abbasid Caliphs.[74]

Baghdad was captured in 1394, 1534, 1623 and 1638. The city has been sieged in 812, 865, 946, 1157, 1258 and in 1393 and 1401, by Tamerlane. In 1058, Baghdad was captured by the Fatimids under the Turkish general Abu'l-Ḥārith Arslān al-Basasiri, an adherent of the Ismailis along with the 'Uqaylid Quraysh.[75] Not long before the arrival of the Saljuqs in Baghdad, al-Basasiri petitioned to the Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Mustansir to support him in conquering Baghdad on the Ismaili Imam's behalf. It has recently come to light that the famed Fatimid da'i, al-Mu'ayyad al-Shirazi, had a direct role in supporting al-Basasiri and helped the general to succeed in taking Mawṣil, Wāsit and Kufa. Soon after,[76] by December 1058, a Shi'i adhān (call to prayer) was implemented in Baghdad and a khutbah (sermon) was delivered in the name of the Fatimid Imam-Caliph.[76] Despite his Shi'i inclinations, Al-Basasiri received support from Sunnis and Shi'is alike, for whom opposition to the Saljuq power was a common factor.[77]

On 10 February 1258, Baghdad was captured by the Mongols led by Hulegu, a grandson of Genghis Khan (Chingiz Khan), during the siege of Baghdad.[78] Many quarters were ruined by fire, siege, or looting. The Mongols massacred most of the city's inhabitants, including the caliph Al-Musta'sim, and destroyed large sections of the city. The canals and dykes forming the city's irrigation system were also destroyed. During this time, in Baghdad, Christians and Shia were tolerated, while Sunnis were treated as enemies.[79] The sack of Baghdad put an end to the Abbasid Caliphate.[80] It has been argued that this marked an end to the Islamic Golden Age and served a blow from which Islamic civilization never fully recovered.[81]

At this point, Baghdad was ruled by the Ilkhanate, a breakaway state of the Mongol Empire, ruling from Iran. In August 1393, Baghdad was occupied by the Central Asian Turkic conqueror Timur ("Tamerlane"),[82] by marching there in only eight days from Shiraz. Sultan Ahmad Jalayir fled to Syria, where the Mamluk Sultan Barquq protected him and killed Timur's envoys. Timur left the Sarbadar prince Khwaja Mas'ud to govern Baghdad, but he was driven out when Ahmad Jalayir returned.

In 1401, Baghdad was again sacked, by Timur, a Central Asian Turko-Mongol figure.[83] When his forces took Baghdad, he spared almost no one, and ordered that each of his soldiers bring back two severed human heads.[84] Baghdad became a provincial capital controlled by the Mongol Jalayirid (1400–1411), Turkic Kara Koyunlu (1411–1469), Turkic Ak Koyunlu (1469–1508), and the Iranian Safavid (1508–1534) dynasties.

Ottoman and Mamluks (16th–19th centuries)

[edit]The Safavids took control of the city in 1509 under the leadership of Shah Ismail I. It remained under Safavid rule until the Ottomans seized it in 1535, but the Safavids regained control in 1624. A massacre occurred when the Shah's army entered the city. It remained under Safavid rule until 1639 when Sultan Murad IV recaptured it in 1638.

In 1534, Baghdad was captured by the Ottoman Empire,[85] becoming the administrative capital of Ottoman Iraq.[3] Under the Ottomans, Baghdad continued into a period of decline, partially as a result of the enmity between its rulers and Iranian Safavids, which did not accept the Sunni control of the city. Between 1623 and 1638, it returned to Iranian rule before falling back into Ottoman hands.[86] Baghdad has suffered severely from visitations of the plague and cholera,[87] and sometimes two-thirds of its population has been wiped out.[88] The city became part of an eyalet and then a vilayet.[89]

For a time, Baghdad had been the largest city in the Middle East.[90] The city saw relative revival in the latter part of the 18th century, under Mamluk government.[90] Direct Ottoman rule was reimposed by Ali Rıza Pasha in 1831.[90] From 1851 to 1852 and from 1861 to 1867, Baghdad was governed, under the Ottoman Empire by Mehmed Namık Pasha.[90] The Nuttall Encyclopedia reports the 1907 population of Baghdad as 185,000.[90]

The city's municipality was established in 1868, and Ibrahim al-Daftari was appointed its first mayor.[91] The year 1869 is of great importance in the history of Baghdad in the Ottoman era, as it was the beginning of what can be considered a distinct era of the Ottoman eras, the foundations of which were laid by Governor Midhat Pasha, who implemented a number of reform systems and laws that the state legislated during the era of reforms and reconstruction, which was called the Tanzimat era.[91] The overall importance of Baghdad to the Ottomans was that they made the headquarters of the Sixth Corps of the Ottoman Army in the city.[91]

By the 19th century, Baghdad emerged as a leading center for Jewish learning.[92] The city had Jewish population of over 6,000 and had numerous yeshivas.[92] The Jewish population has grown so rapidly that by 1884, there were 30,000 Jews in Baghdad and by 1900, around 50,000, comprising over a quarter of the city's total population.[92] Large-scale Jewish immigration from Kurdistan to Baghdad continued throughout this period.[92] By the mid-19th century, the religious infrastructure of Baghdad grew to include a large yeshiva which trained up to sixty rabbis at time.[92] Religious scholarship flourished in Baghdad, which produced great rabbis, such as Joseph Hayyim ben Eliahu Mazal-Tov, known as the Ben Ish Chai (1834–1909) or Rabbi Abdallah Somekh (1813–1889). During this time, Baghdadi Jews established a successful trade diaspora in China, India and Singapore.

-

Baghdad Eyalet in 1609

-

Baghdad Vilayet in 1900

-

Souk in Baghdad, 1876

Modern era

[edit]

Baghdad and southern Iraq remained under Ottoman rule until 1918, when they were captured by the British during World War I.[93] In 1920, a revolt erupted in Baghdad against new British policies.[94] It began in summer with mass demonstrations by Iraqis, including protests by embittered officers from the old Ottoman Army.[95] The revolt gained momentum and spread to the middle and lower Euphrates.[96] The British authorities retaliated by air bombing across Baghdad, which killed thousands of residents.[97] In 1921, under the Mandate of Mesopotamia, Baghdad became the capital of the British-protected monarchy. Baghdad was made capital of the independent kingdom of Iraq in 1932.

Several architectural and planning projects were commissioned to reinforce this administration.[98] During this period, the substantial Jewish community (probably exceeding 100,000 people) comprised between a quarter and a third of the city's population. The National Museum of Iraq and the University of Baghdad were built by King Faisal, who laid foundation for the modern Iraqi state. The city's population grew from an estimated 145,000 in 1900 to 580,000 in 1950.[99] A development plan came in 1957, visioned by Frank Lloyd Wright.[99] The plan proposed to build a cultural hub on an island on the river, with an opera house, museums, a university, shopping malls, and a 300-foot statue of the fifth Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid.

On 1 April 1941, members of the "Golden Square" led by former minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani staged a coup in Baghdad and installed a pro-German and pro-Italian government to replace the pro-British government of Regent Abd al-Ilah.[100][101] The British forces intervened in the resulting Anglo-Iraqi War.[102] Fearing the advancement, Gaylani and his government had fled, and the mayor of Baghdad surrendered to the British and Commonwealth forces.[101][103] On 1–2 June, during the ensuing power vacuum, Jewish residents were attacked following rumors they had aided the British.[104] In what became known as the Farhud, over 180 Jews were killed and 1,000 injured, 900 Jewish homes were destroyed, and hundreds of Jewish properties were ransacked.[104][105] Many Jewish girls were raped and children maimed in front of their families.[106] Between 300 and 400 non-Jewish rioters were killed in the attempt to quell the violence.[107] Between 1950 and 1951, Jews were targeted in series of bombings.[108] According to Avi Shlaim, Israel was behind bombings.[108]

On 14 July 1958, a significant portion of the Iraqi Army under Abdul-Karim Qasim, staged a coup to topple the Kingdom of Iraq.[109] The army seized control over Baghdad and stormed the radio station and the Al-Rehab Palace.[110][111] Many people were brutally killed during the coup, including King Faisal II, former Regent Abd al-Ilah and former Prime Minister Nuri al-Said and members of the royal family.[111] Many of the royal figures' bodies were dragged through the streets and mutilated. Mob violence emerged and several foreign nationals staying at the Baghdad Hotel, including Americans and Jordanians were killed.[111] New principles were adopted for the city's development. New Baghdad and Sadr City were developed during the reign of Qasim. In 1960, Baghdad hosted an international conference with dignitaries from Iran, Venezuela and Saudi Arabia, that founded Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).[112]

During the 1970s, Baghdad experienced a period of prosperity and growth because of a sharp increase in the price of petroleum, Iraq's main export.[113] New infrastructure including oil pipelines, modern sewerage, and highways were built.[114] Master plans of the city (1967 and 1973) were delivered by the Polish planning office Miastoprojekt-Kraków, mediated by Polservice.[114] Saddam Hussein sponsored architectural and artwork events, that attracted world's popular architects.[115] The city had a vibrant lifestyle.[116] Baghdad was called as "Nuremberg of 1930s" and "Las Vegas of the 1980s".[116]

However, the Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s was a difficult time for the city, as money was diverted to the military and thousands of residents endured devastations.[117] Iran launched a number of missiles and rockets on Baghdad, some of them hitting dangerously close to Al-Rashid Street and the Jewish Quarter.[118][119][120] Power plants and oil refineries were damaged.[118] A nuclear reactor near Baghdad was destroyed in an airstrike by Israel.[121] Despite the war, preparations were underway for Baghdad to host a Non-Alignment Movement summit.[114] Conference centers and hotels such as Palestine Hotel, Al-Mansour Hotel and Ishtar Hotel were built.[114] However, the summit was later shifted to New Delhi, due to deteriorating security.[122][123]

During the Gulf War, Baghdad was the most heavily defended area of Iraq.[124][125] Initially, U.S. airstrikes on Baghdad failed and resulted a tactical victory for the Iraqi Air Force.[126][127] Later, the multionational forces preeceded with aerial bombings.[128] Air defense, communication systems, bridges, chemical weapon facilities, and artilleries were damaged.[129] Oil refineries and airport were targeted.[129] On 13 February 1991, an aerial bombing attack in Amiriya killed at least 408 civilians.[130][131] Shortly after the end of the war, ethnic Kurds and Shi'a Muslims led uprisings against the government.[123] Clashes took place Shi'a rebels and the Republican Guard led by Qusay Hussein.[132] Sadr City was besieged until the order restored.[133] Another uprising occurred in 1999, after Ayatollah Muhammad Sadiq al-Sadr was assassinated in Najaf.[134] Unrest began as large scale protests took place in Shia neighborhoods of Baghdad, specially Saddam City.[134] The Republican Guard deployed in the district suppressed the demonstration, leaving between 27 and 100 dead.[134]

Baghdad was targeted in frequent U.S. airstrikes.[135] On 26 June 1993, cruise missiles were launched into downtown Baghdad, targeting the intelligence headquarters in the Mansour district.[136] The attack killed nine civilians nearby, including actress and painter Layla Al-Attar.[137] During the 1998 bombing of Iraq, missiles struck multiple locations across Baghdad, including presidential palaces, several Republican Guard barrakcs, and offices of the Ministry of Defense and the Military industry. On February 16, 2001, the U.S. launched air strikes on five military targets at Taji.[138][139]

21st century (2001–present)

[edit]

The city was economically drained, as a result of the Gulf War and the subsequent embargo against Iraq.[140] By the end of the 1990s, the government made improvements and began rebuilding Baghdad.[141] Government offices, presidential palaces, bridges and roads damaged in the war and follow-up U.S. attacks were restored.[142] The city's airport was reopened, with flights from Lebanon, Syria and Jordan.[142] Numerous mosques were built as a part of the Faith Campaign. In 2001, a broad initiative came to restore Baghdad's cultural heritage.[143] Older mosques, churches, mandis and synagogues were restored and other historical structures were rebuilt.[144][145] Under Saddam's architectural vision, a large number of palaces were built around the city.[146] However, these efforts were interrupted by the war which began in 2003.[147][148][149]

In 2003, the United States-led coalition invaded Iraq.[150] Coalition forces launched massive aerial assaults.[150] The resistance of the Iraqi Army of the city's airport delayed coalition's entry into Baghdad.[151] Following the fall of Baghdad on 9 April 2003, the government lost its power.[150] A statue of Saddam was toppled in Firdous Square, symbolizing the end of his rule.[150] Many of the former government officials were either killed or captured, while others managed to escape and flee.[152] After the overthrow the government, the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) was formed.[153] CPA's decisions caused a power vacuum.[153][154] Also two minor riots took place in 2003, on 21 July and 2 October, causing some disturbance in the population.[155][156] Shortly after the invasion and the fall of the regime, an insurgancy began against the U.S-led rule of Iraq, consisting of former government officers and Islamist groups.[157] Bombings took place at Jordanian Embassy and Canal Hotel.[158] Religious and ethnic minorities,— Christians, Mandaeans, and Jews, began leaving the city out of fear of being targeted in attacks, as they were subjected to kidnappings, death threats, and violence.[158] The Iraqi Film Archives site was bombed, priceless collection of artifacts in the National Museum was looted, and thousands of ancient manuscripts in the National Library were destroyed.[158][159] The Haifa Street helicopter incident on 12 September was controversial.[158] On the eve of Ashura on 2 March 2004, one of the deadliest bombing took place in Baghdad, that killed at least 80–100 and injured 200 Shi'a Muslims.[158] In 2005, over 965 people were killed in Al-Aimmah Bridge near Al-Kadhimiya Mosque.[160] Attempts were made to rescue people, specially from the Sunni district of Adhamiyah, which is today seen as a symbol of unity.[160]

Coinciding the execution of Saddam Hussein in 2006, violence increased during the civil war between Shi'ite militias and Sunni insurgents.[158] Shi'ite militias were Muqtada as-Sadr's Jaysh al-Mahdi (JAM) and the Iranian-backed Special Groups and among Sunni insurgents, the largest was Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI).[158] Sunni insurgents established their bases Mansour, Adhamiyah and Doura.[158] Mansour district borders the Shi'ite populated Kadhimiyah and East Rasheed.[158] Before 2003, it was home to wealthy Sunnis and Ba'athist officials.[158] Hence, when the regime fell, it quickly became a stronghold for the Sunni insurgency.[158] While Shia militias were based in Sadr City, Kadhimiyah, and West Rasheed, with Bab Al-Sharqi becoming stronghold for the Mahdi Army.[158] Later, they also expanded into the surrounding districts of eastern Baghdad. 9 Nissan, Karadah, and Rusafa were dominated by Shias.[158]

Under Operation Imposing Law (Operation Fardh al-Qanoon), the coalition forces and post-2003 Iraqi Army successfully defeated Al-Qaeda and targeted Shia militias.[158] By 2009, the level of violence decreased.[158] However, violence continued.[158] The period surrounding Provincial Elections was remarkably peaceful.[158] But Baghdad witnessed an uptick in attacks in early April 2009, when a series of suicide bomb and vehicle-borne improvised explosive device attacks were perpetrated across the capital. [158] The war and subsequent occupation ended in 2011, that caused huge damage to Baghdad's transportation, power, and sanitary infrastructure.[150] It resulted in massive civilian casualties, whose number is disputed.[158]

Though the war ended, but an Islamist insurgency lasted until 2013.[161][162] Baghdad experienced anti-government protests by Sunnis during the Arab Spring. It was followed by another war from 2013 to 2017 and a low-level insurgency from 2017, which included suicide bombings in January 2018 and January 2021.[163] It has been site of clashes between the citizens and the government. The city attracted global media attention on 3 January 2020, when Iranian general Qasem Soleimani was assassinated in a U.S. drone strike near Baghdad Airport.[164] In December 2015, Baghdad was selected by UNESCO as the first Arab city of the center of literary creativity.[165]

Geography

[edit]

The city is located on a vast plain bisected by the Tigris river. The Tigris splits Baghdad in half, with the eastern half being called "Risafa" and the Western half known as "Karkh". The land on which the city is built is almost entirely flat and low-lying, being of quaternary alluvial origin due to periodic large flooding of the Tigris river. The Diyala river is a tributary of the Tigris, flowing southeast of the city and bordering its eastern suburbs.

Baghdad is 529.8 kilometres (329.2 mi) northwest of Basra, 402.9 kilometres (250.4 mi) south of Mosul, 366.8 kilometres (227.9 mi) south of Erbil and 103.8 kilometres (64.5 mi) northeast of Karbala.[166] Located to the south is Mahmoudiyah, which serves as the gateway to Baghdad.

Climate

[edit]Baghdad has a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh), featuring extremely hot, prolonged, dry summers and mild to cool, slightly wet, short winters. In the summer, from June through August, the average maximum temperature is as high as 44 °C (111 °F) and accompanied by sunshine. Rainfall has been recorded on fewer than half a dozen occasions at this time of year and has never exceeded 1 mm (0.04 in).[167] Even at night, temperatures in summer are seldom below 24 °C (75 °F). Baghdad's record highest temperature of 51.8 °C (125.2 °F) was reached on 28 July 2020.[168][169] Humidity is under 50% in summer, due to Baghdad's distance from both the marshes in southern Iraq and the coasts of the Persian Gulf. Dust storms from the deserts to the west are a normal occurrence during the summer.

Its winter temperatures are those of a hot desert climate. From December through February, Baghdad has maximum temperatures averaging 16 to 19 °C (61 to 66 °F), with highs possible above 21 °C (70 °F). Lows below freezing occur statistically a couple of times per year.[170]

Annual rainfall, almost entirely confined to the period from November through March, averages approximately 150 mm (5.91 in), but has been as high as 338 mm (13.31 in) and as low as 37 mm (1.46 in).[167] On 11 January 2008, light snow fell across Baghdad for the first time in 100 years.[171] Snowfall was again reported on 11 February 2020, with accumulations across the city.[172]

| Climate data for Baghdad (1991-2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

36.6 (97.9) |

42.0 (107.6) |

46.7 (116.1) |

49.6 (121.3) |

51.8 (125.2) |

50.0 (122.0) |

48.4 (119.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

35.6 (96.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

51.8 (125.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

37.1 (98.8) |

42.2 (108.0) |

44.7 (112.5) |

44.5 (112.1) |

40.3 (104.5) |

34.0 (93.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

29.5 (85.1) |

33.4 (92.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.7 (60.3) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.0 (12.2) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 24.6 (0.97) |

16.6 (0.65) |

15.7 (0.62) |

16.2 (0.64) |

3.3 (0.13) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

7.6 (0.30) |

23.6 (0.93) |

17.0 (0.67) |

124.7 (4.91) |

| Average precipitation days | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 34 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.1 | 58.9 | 48.7 | 41.1 | 31.4 | 24.4 | 23.8 | 25.7 | 30.9 | 41.6 | 57.9 | 68.0 | 43.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 192.2 | 203.4 | 244.9 | 255.0 | 300.7 | 348.0 | 347.2 | 353.4 | 315.0 | 272.8 | 213.0 | 195.3 | 3,240.9 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Source 1: WMO (precipitation days 1976-2008)[173][174] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate & Temperature[175][176] | |||||||||||||

Governance

[edit]

Administratively, Baghdad Governorate is divided into districts which are further divided into sub-districts.[177] Municipally, the governorate is divided into 9 municipalities, which have responsibility for local issues.[177] Regional services, however, are coordinated and carried out by a mayor who oversees the municipalities.[177] The governorate council is responsible for the governorate-wide policy.[177] These official subdivisions of the city served as administrative centers for the delivery of municipal services but until 2003 had no political function.[177] Beginning in April 2003, the U.S—controlled Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) began the process of creating new functions for these.[177] The process initially focused on the election of neighborhood councils in official neighborhoods, elected by neighborhood caucuses.[177] The CPA convened a series of meetings in each neighborhood to explain local government, to describe the caucus election process and to encourage participants to spread the word and bring friends, relatives and neighbors to subsequent meetings.[177]

Each neighborhood process ultimately ended with a final meeting where candidates for the new neighborhood councils identified themselves and asked their neighbors to vote for them.[177] Once all 88 neighborhood councils were in place, each neighborhood council elected representatives from among their members to serve on one of the city's nine district councils.[177] The number of neighborhood representatives on a district council is based upon the neighborhood's population.[177] The next step was to have each of the nine district councils elect representatives from their membership to serve on the 37 member Baghdad City Council.[177] Later, the number of official neighborhoods were increased to 89.[177] This three tier system of local government connected the people of Baghdad to the central government through their representatives from the neighborhood, through the district, and up to the city council.[177] The same process was used to provide representative councils for the other communities in Baghdad Province outside of the city itself.[177] There, local councils were elected from 20 neighborhoods (Nahia) and these councils elected representatives from their members to serve on six district councils (Qada).[177]

As within the city, the district councils then elected representatives from among their members to serve on the 35 member Baghdad Regional Council. The first step in the establishment of the system of local government for Baghdad Province was the election of the Baghdad Provincial Council. As before, the representatives to the Provincial Council were elected by their peers from the lower councils in numbers proportional to the population of the districts they represent. The 41 member Provincial Council took office in February 2004 and served until national elections held in January 2005, when a new Provincial Council was elected. This system of 127 separate councils may seem overly cumbersome; however, Baghdad Province is home to approximately seven million people. At the lowest level, the neighborhood councils, each council represents an average of 75,000 people. The nine District Advisory Councils (DAC) are as follows:[177]

The nine districts are subdivided into 89 smaller neighborhoods which may make up sectors of any of the districts above. The following is a selection (rather than a complete list) of these neighborhoods:

- Al-Ghazaliya

- Al-A'amiriya

- Dora

- Karrada

- Al-Jadriya

- Al-Hebnaa

- Zayouna

- Al-Saydiya

- Al-Sa'adoon

- Al-Shu'ala

- Al-Mahmudiyah

- Bab Al-Moatham

- Al-Za'franiya

- Hayy Ur

- Sha'ab

- Hayy Al-Jami'a

- Al-Adel

- Al Khadhraa

- Hayy Al-Jihad

- Hayy Al-A'amel

- Hayy Aoor

- Al-Hurriya

- Haydar-Khana

- Hayy Al-Shurtta

- Yarmouk

- Jesr Diyala

- Abu Disher

- Al-Maidan

- Raghiba Khatoun

- Arab Jibor

- Al-Fathel

- Al-Ubedy

- Al-Washash

- Al-Wazireya

- Bataween

Notable streets

[edit]

- Haifa Street

- Hilla Road – Runs from the north into Baghdad via Yarmouk (Baghdad)

- Caliphs Street – site of historical mosques and churches

- Al-Sa'doun Street – stretching from Liberation Square to Masbah

- Abu Nuwas Street – runs along the Tigris from the Jumhouriya Bridge to 14 July Suspended Bridge

- Damascus Street – goes from Damascus Square to the Baghdad Airport Road

- Mutanabbi Street – A street with numerous bookshops, named after the 10th century Iraqi poet Al-Mutanabbi

- Rabia Street

- 14 July Street (Mosul Road)

- Muthana al-Shaibani Street

- Bor Saeed (Port Said) Street

- Thawra Street

- Al-Qanat Street – runs through Baghdad north-south

- Al-Khat al-Sare'a – Mohammed al-Qasim (high speed lane) – runs through Baghdad, north–south

- Industry Street runs by the University of Technology – center of the computer trade in Baghdad

- Al Nidhal Street

- Al-Rasheed Street – city center Baghdad

- Al-Jumhuriya Street – city center Baghdad

- Falastin Street

- Tariq al-Muaskar – (Al-Rasheed Camp Road)

- Akhrot street

- Baghdad Airport Road[185]

Demographics

[edit]Baghdad's population was estimated at 7.22 million in 2015. The surrounding metropolitan region's population is estimated to be 10,500,000.[5] It is second largest city in the Arab world after Cairo and fourth largest metropolitan area in the Middle East after Tehran.[5] At the beginning of the 21st century, some 1.5 million people migrated to Baghdad.[5] The 2013–2017 civil war following the Islamic State's invasion in 2014 caused hundreds of thousands of Iraqi internally displaced people to flee to the city.[5]

Ethnicity

[edit]

The vast majority of Baghdad's ethnic population are Iraqi Arabs, while minority groups include Kurds, Feyli, Kurdish, Turkmen, Assyrians, Kawliya, Circassians, Mandaeans, and Armenians.[5][186][187] Post-2003 have left an impact of Baghdad's ethnic composition.[188] In 2003, approximately 500,000 Kurds lived in Baghdad.[188] As of 2016, around 300,000 remained in Baghdad.[188] Among them, about 150,000 are Shi'a mostly of Luri origin.[189] The main Kurdish neighborhood is situated in central Baghdad, known as the Quarter of Kurds (Akd al–Akrad).[190] It is itself home to more than 200 Kurdish families that have lived for generations.[191][192]

Christians in Baghdad are predominantly ethnic Assyrians and Armenians.[193] Assyrians began moving to Baghdad by the mid 20th century from northern Iraq and Iran.[193][194][195] The historic "Assyrian Quarter" of the city – Dora, which boasted a population of 150,000 Assyrians in 2003, made up over 3% of the capital's Assyrian population then.[196] The community has been subject to kidnappings, death threats, vandalism, and house burnings by al-Qaeda and other insurgent groups.[196] As of the end of 2014, only 1,500 Assyrians remained in Dora and others in Karrada district.[196] Before the war, 25,000 Armenians lived in Iraq, with majority them concentrated in Baghdad.[195] Although the Armenian population has reduced, Baghdad is still home to the largest community of Armenians in Iraq, primarily concentrated in the Armenian quarter of Bab al-Sharqi area.[197]

An estimated 60,000 Iraqi Turkmen live in Baghdad, with significant population in the neighborhoods of Adhamiyah and Ragheba Khatun.[198][199][200] There is a Circassian neighborhood in the city, which is home to the largest Circassian community of Iraq.[201][202][203] The metropolitan area and the adjoining governorate is also home to Kawliya, African Iraqis, Chechens and other groups.[204][205][206]

Religion

[edit]

The majority of the citizens are Muslims with minorities of Christians, Yezidis, Jews and Mandeans also present.[207] There are many religious centers distributed around the city including mosques, churches, synagogues and Mashkhannas cultic huts.[207] The city historically has a predominantly Sunni population, but by the early 21st century around 52% of the city's population were Shi'ites.[5] Sunni Muslims make up 29–34% of Iraq's population and they are still a majority in west and north Iraq.[208] As early as 2003, about 20% of the population of the city was the result of mixed marriages between Shi'ites and Sunnis.[208][5] Following the civil war between Sunni and Shia militia groups during the occupation of Iraq, the population of Sunnis significantly decreased as they were pushed out of many neighborhoods.[5] Today majority of the neighborhoods are either entirely Sunni or Shi'ite. While few localities are mixed, such as Yarmouk.

The Christian community in Baghdad is divided among various denominations, mainly the Chaldean Catholic Church and the Syriac Catholic Church.[209] There is also a significant presence of followers of the Assyrian Church of the East and the Syriac Orthodox Church, along with the largest Armenian Apostolic and Protestant communities in Iraq, which is also located in Baghdad.[210] The city serves as the headquarters of the Chaldean Catholic Church, with its see located in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Sorrows,[211] while the Ancient Church of the East has its see in the Cathedral of the Virgin.[209] Before the Iraq War in 2003, Baghdad was home to 300,000–800,000 Christians,[212][209] primarily concentrated in several neighborhoods with a Christian majority or significant minority, the most notable being Karrada and al–Dora, which had around 150,000 Christians.[213] After 2003, a large number of Christians were displaced in wars and many of them fled to Baghdad after ISIS's takeover of Mosul. Today about 100,000 Christians remained in Baghdad, primarily in Karrada and Mansour district.[214][215]

Baghdad was once home to one of the world's most significant Jewish communities.[216] In 1948, Jews numbered approximately 150,000, constituting 33% of the city's population.[217] Persecution forced most Jews to flee Iraq.[218] Even after 1948, up to 100,000 Jews remained, which decreased.[219] Majority of 15,000 Iraqi Jews lived in Baghdad during Saddam Hussein's rule and their population dwindled, not due to persecution but because of lifted travel restrictions that allowed many to emigrate.[218] By 2003, Iraq still had a Jewish community of about 1,500 people, majority of whom resided in Baghdad.[218] But the population decreased sharply after the war.[218] Today, an estimated 160 Jews live in Baghdad out of spotlight, primarily in the old Jewish quarters of Bataween and Shorja, which was once home to vibrant Jewish community.[220][221] The city was historically home to over 60 synagogues, cemeteries, and shrines, many of which were preserved before 2003.[220] However, their condition deteriorated after the war, and only a few sites, such as the Meir Taweig Synagogue and Al-Habibiyah Jewish Cemetery, remain today.[220][222]

Beyond their traditional homelands, around Amarah and Basra, Mandaeans are also found in Baghdad.[223] By the late 20th century, Mandaeans began settling in Baghdad for better opportunities.[223] Most of them live primarily around al-Qadisiyah and Dora, which is location to their place of worship and cultural centers.[223] However, persecution of Mandaeans have been greatly decreased since 2003.[223] There is also a small of community of Baha'is and Sikhs, who live in Baghdad.[224] The Sikhs are mostly Indians.[5] Before 2003, Baghdad was regularly visited by Sikh pilgrims from India.[5]

-

Mandaean Mandi of Baghdad

-

Interior of the Cathedral of Our Lady of Sorrows (headquarter of the Chaldean Catholic Church)

Economy

[edit]Baghdad serves as the commercial and financial hub, home to 22% of the population, and generating 40% of the Iraq's GDP.[225] It connects trade routes between Turkey, Syria, India, and Southeast Asia.[226] As the capital, it hosts government institutions and state enterprises, key sources of employment.[226] The public education system follows Ba'athist socialist ideologies, for employment in the public sector.[227] Since 2003, the public sector has struggled to provide jobs, and the private sector hasn't grown sufficiently, leading companies to hire mainly foreigners.[227] To address this, NGOs are establishing incubation centers in the city.[228]

Baghdad serves as headquarters for important companies of Iraq, such as Iraq National Oil Company, State Organization for Marketing of Oil and Iraqi Airways.[226] Baghdad is home to large insurance companies and banks — Central Bank of Iraq, Rafidain Bank, and Rashid Bank and regional headquarters for First Abu Dhabi Bank, Fransabank and Saudi National Bank.[229] Multinational companies such as Honeywell, Shell, General Electric, SalamAir and Robert Bosch GmbH have established their regional base.[229] Baghdad is also home to Iraq Stock Exchange, that was established in 1992. Most of these establishments are located in Al-Rasheed Street, Karrada and Mansour district.[226]

It was once one of the main destinations in the region with a wealth of cultural attractions.[230] Tourism has diminished due to wars, but in recent years the city has a revival in tourism although still facing challenges.[231] There are numerous historic, scientific and artistic museums in Baghdad.[232][233] Religious tourism in Baghdad has grown since 2003, with sites like Al-Kadhimiya Mosque, Abu Hanifa Mosque, Mausoleum of Abdul-Qadir Gilani, and Buratha Mosque attracting visitors from Iran, Pakistan, and India, while non-religious tourists mainly come from Turkey, France, and the United States.[234] Around 1 million people visit the city annually for religious purposes.[234] The pilgrims are both Shia and Sunni Muslims.[235]

The city contains the factories of carpets, leather and textiles, workshops, cement and tobacco factories.[236] Industrial areas extend from the city center to outside and suburbs in the metropolitan area, such as Taji and northern Baghdad.[236] Subsequently, it has produced a wide variety of consumer and industrial goods, including processed foods and beverages, clothes, footwear, wood products, furniture, paper and printed material, bricks, chemicals, plastics, electrical equipment, and metal and nonmetallic products.[236] Bismayah, southeast of Baghdad, is home to world's largest precast factory.[229] In agricultural aspect, palm groves are spread in the city, and many of its people depends on the cultivation of many yields.[229]

Baghdad, like other provinces such as Babylon, Karbala and Qadissiya, contains metals such as aluminum, ceramics, nickel, manganese and chromium, whose size is not yet known, being recently discovered by local Iraqi cadres lacking experience and mechanisms to determine the size of these explorations.[229] An oilfield is located in eastern Baghdad.[237] It was believed that the quantities of oil is modest, but the drilling disclosed that its size exceeds the initial estimates, and has northern extensions in the province of Salah al-Din, and southern province of Wasit.[237] The city is also home to Dora Refinery, a large oil refinery in Dora, which is the 3rd largest in Iraq in terms of production.[229] The production of it exceeds 200,000 barrels (32,000 m3) per day, while its total production estimated if it was developed up to 120,000 barrels (19,000 m3) per day.[229]

Most reconstruction efforts have been devoted to the restoration and repair of badly damaged urban infrastructure.[238] Some of the private projects includes Baghdad Renaissance Plan, Sindbad Hotel Complex and Conference Center, and Central Bank of Iraq Tower. Other project proposed includes Romantic Island and Baghdad Gate.[239][240] Numerous projects have been also impacted due to corruption.[241] According to a report published by CNBC, there are around 150 entertainment projects planned for the city.[242] Many of them were delayed due to government policies.[242] Also Baghdad has witnessed the opening of dozens of tourist complexes annually with areas reaching 20,000 square metres (4.9 acres) in addition to some major tourism projects with areas exceeding 50,000 square metres (12 acres) with the aim of investment combining trade and tourism as a distinctive economic model.[242] In recent years, Baghdad has also adopted modern economic trends like, establishment of startup hubs, office space and incubation center, as well as development of shopping malls such Baghdad Mall and Dijlah Village.[228]

Transportation

[edit]

Baghdad lacks substantial public transportation, and taxis are the primary means of transportation in the city. Roads in Baghdad are noted to be especially congested and this began since 2003.[243] According to MP Jassim Al-Bukhati in 2021, "Baghdad's roads are designed to accommodate 700,000 cars, while now there are between 2.5 and 3 million cars on them".[244] It is because since 2003, import of car has increased.[244] Since then water transport from river have become a popular mode of transport. Use of boats crossing across the river saves time for travelers to escape congestion.[245] Private organizations are working to improve transport system.[246][247] Among the major bridges connecting Karkh and Rusafa are 14th of July Bridge, Al-Aimmah Bridge and Al-Sarafiya Bridge.[248] In 2023, the authorities announced to build 19 bridges in Baghdad.[248] It is a part of its post-war reconstruction efforts, as many bridges were damaged during the war.[248] Streets, avenues and alleys plays an important role in creating network of transport.[249] Al-Sa'doun Street stretches from Liberation Square to Masbah.[249] Abu Nuwas Street runs along the Tigris from the Jumhouriya Bridge to 14 July Suspended Bridge.[249] Damascus Street goes from Damascus Square to the Baghdad Airport Road.[249] Hilla Road runs from the north into Baghdad via Yarmouk.[249] Mutanabbi Street is a street with numerous bookshops, named after the 10th century Iraqi poet Al-Mutanabbi.[249] Caliphs Street is the site of historical mosques and churches.[249]

Air transport

[edit]Iraqi Airways, the national airline of Iraq, operates out of Baghdad International Airport in Baghdad.[250] The airport was opened by Saddam Hussein in 1982 as Saddam International Airport.[250] It was closed as result of the Gulf War and subsequent embargo.[251] The airport was reopened in August 2000.[251] The airport adopted its current name after the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[251]

Planned Baghdad Metro

[edit]The Baghdad Metro project was first proposed during the 1970s but did not come to fruition due to wars and sanctions. After the Iraq war, Iraqi authorities intended to revive the project, but it was again delayed due to domestic instability.[252] In 2019, it was reported that Korean Hyundai and French Alstom would be building the metro.[253] However, the planned construction did not happen.

As of February 2024, the current plan consisted of fully electric and automated (driverless) trains running on an extensive railway network including an underground railway portion as well as an elevated railway. The proposed Baghdad Metro system includes seven main lines with a total length of more than 148 kilometres, 64 metro stations, four workshops and depots for trains, several operations control centers (OCC) and seven main power stations (MPS) with a capacity of 250 mega-watts, and several Global System for Mobile Communication (GSM) towers. The metro will be equipped with CCTV and internet as well as USB ports for charging. Special compartments will be allocated for women and children as well as seats for people with special needs, pregnant women, and the elderly. The metro stations will be connected to other public transport networks such as buses and taxis, and 10 parking spaces will be available for commuters. The planned operating speed will be 80–140 km/hour with an estimated 3.25 million riders per day.[254]

In July 2024, it was announced that an international consortium of German French, Spanish, and Turkish companies was awarded $17.5 billion contract to construct Baghdad's metro.[255] The consortium includes Alstom, Systra, SNCF, Talgo, Deutsche Bank and SENER. The consortium was then to negotiate the technical, financial and operational details of the project which is now estimated to be completed in May 2029.[256]

Cityscape

[edit]The Round City was the core of the city, during the establishment of Baghdad. It ceased to exist, as a result of the Mongolian siege. Urban features such as streets, avenues, alleyways and squares clusters a large number of landmarks, which itself creates an identity of cultural or intellectual hubs and define the beauty of Baghdad.

Al-Rasheed Street is one of the most significant landmarks in Baghdad. Located in al-Rusafa area, the street was an artistic, intellectual and cultural center for many Baghdadis. It also included many prominent theaters and nightclubs such as the Crescent Theatre where Egyptian Singer Umm Kulthum sang during her visit in 1932 as well as the Chakmakji Company that recorded the music of various Arab singers.[257] The street also contains famous and well-known landmarks including the ancient Haydar-Khana Mosque as well as numerous well-known cafés such as al-Zahawi Café and the Brazilian Café.[258][259]

Mutanabbi Street is located near the old quarter of Baghdad; at Al-Rasheed Street. It is the historic center of Baghdadi book-selling, a street filled with bookstores and outdoor book stalls. It was named after the 10th-century classical Iraqi poet Al-Mutanabbi.[260] This street is well established for bookselling and has often been referred to as the heart and soul of the Baghdad literacy and intellectual community.[260] Firdos Square is a public open space in Baghdad and the location of two of the best-known hotels, the Palestine Hotel and the Sheraton Ishtar, which are both also the tallest buildings in Baghdad.[261] The square was the site of the statue of Saddam Hussein that was pulled down by the coalition forces in a widely televised event during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Qushla or Qishla is a public square and the historical complex located in al-Rusafa neighborhood at the riverbank of Tigris.[262] The place and its surroundings is where the historical features and cultural capitals of Baghdad are concentrated, from the Mutanabbi Street, Abbasid-era palace and bridges, Ottoman-era mosques to the Mustansariyah Madrasa.[262] The square developed during the Ottoman era as a military barracks.[262] Today, it is a place where the citizens of Baghdad find leisure such as reading poetry in gazebos.[262] It is characterized by the iconic clock tower which was donated by George V.[262] The entire area is submitted to the UNESCO World Heritage Site Tentative list.[263]

Architecture

[edit]During the 1970s and 1980s, Saddam Hussein's government spent a lot of money on new monuments, mosques, palaces and hotels.[264] The Street is also notable for its architecture and aesthetic which was inspired by Renaissance architecture and also includes the famous Iraqi shanasheel.[265]

Modern Landmarks

[edit]

The National Museum of Iraq whose collection of artifacts was looted during the invasion, and the iconic Hands of Victory arches.[266] Multiple political parties are in discussions as to whether the arches should remain as historical monuments or be dismantled.[266] Thousands of ancient manuscripts in the National Library were destroyed under Saddam's command.[266]

Grand Festivities Square is the main square where public celebrations are held and is also the home to three important monuments commemorating Iraqi's fallen soldiers and victories in war; namely Al-Shaheed Monument, the Victory Arch and the Unknown Soldier's Monument.[267] Al-Shaheed Monument, also known as the Martyr's Memorial, is a monument dedicated to the Iraqi soldiers who died in the Iran–Iraq War.[267] However, now it is generally considered by Iraqis to be for all of the martyrs of Iraq, especially those allied with Iran and Syria fighting ISIS, not just of the Iran–Iraq War.[267] The monument was opened in 1983, and was designed by the Iraqi architect Saman Kamal and the Iraqi sculptor and artist Ismail Fatah Al Turk.[267] Though these works symbolize the ruling entity.[113] Neverthelsess, they have remained part of architectural legacy, which beautified Baghdad.[113]

Masjid Al-Kadhimain is a shrine that is located in the Kādhimayn suburb of Baghdad.[207][268] It contains the tombs of the seventh and ninth Twelver Shi'ite Imams, Musa al-Kadhim and Muhammad at-Taqi respectively, upon whom the title of Kādhimayn ("Two who swallow their anger") was bestowed.[269][268][207] Many Shi'ites travel to the mosque from far away places to commemorate those imams.[207][268] A'dhamiyyah is a predominantly Sunni area with a Mosque that is associated with the Sunni Imam Abu Hanifa. The name of Al-Aʿẓamiyyah is derived from Abu Hanifa's title, al-Imām al-Aʿẓam (the Great Imam).[270][271]

The historic Jewish quarters of Bataween and Shorja is home to numerous sites that are associated with Jews.[272] These sites were preserved during the Ba'athist regime.[273] However, after 2003, many of them are in poor conditions.[273] Meir Taweig Synagogue is the only active synagogue of Iraq, which have a large compound, that consist of community center, Jewish school and library.[273] Daniel Market (Souq Danial), which was named after Menahem Saleh Daniel, still bears the same name. It is popular for fabrics and shoes.[273] The Great Synagogue of Baghdad, the oldest synagogue of Iraq, is now restored as a museum.[273] Al-Habibiyah Cemetery is the largest Jewish cemetery in Baghdad, home to around 1,000 graves.[273] The Tomb of Joshua, now a Muslim shrine, is believed to be the burial site of Joshua.[273] Shaykh Yitzhak Tomb and Synagogue was preserved until 2003. Today it is neglected. Other sites includes House of Sassoon Eskell and library of Mir Basri.[273]

The Sabian–Mandaean Mandi of Baghdad is a Mandaen temple in al-Qadisiyyah.[274] It is the main community center for Mandaeans in Iraq.[274] Plans are underway to demolish and build a larger one to accommodate more worshippers.[274] A cultural institute for Mandeans is also in Baghdad.[275] The city is home to Baba Nanak Shrine, a sacred site in Sikhism.[5] It was destroyed during the Iraq War in 2003.[5] In the Kadhimiya district of Baghdad, was the house of Baháʼu'lláh, (Prophet Founder of the Baha'i Faith) also known as the "Most Great House" (Bayt-i-Aʻzam) and the "House of God", where Baháʼu'lláh mostly resided from 1853 to 1863. It is considered a holy place and a place of pilgrimage by Baha'is according to their "Most Holy Book".[276] On 23 June 2013, the house was destroyed under unclear circumstances.[224]

Baghdad Zoo used to be the largest zoological park in the Middle East. Within eight days following the 2003 invasion, however, only 35 of the 650 animals in the facility survived.[277] This was a result of theft of some animals for human food, and starvation of caged animals that had no food.[277] Conservationist Lawrence Anthony and some of the zoo keepers cared for the animals and fed the carnivores with donkeys they had bought locally.[277][278] Eventually Paul Bremer, Director of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq after the invasion, ordered protection for the zoo and enlisted U.S. engineers to help reopen the facility.[277] Al-Zawraa Park is also part of the zoo, which is main urban park of the city.[277]

Education

[edit]

The House of Wisdom was a major academy and public center in Baghdad. The Mustansiriya Madrasa was established in 1227 by the Abbasid Caliph al-Mustansir. The name was changed to al-Mustansiriya University in 1963. The University of Baghdad is the largest university in Iraq and the second largest in the Arab world. Prior to the Gulf War, multiple international schools operated in Baghdad, including:

- École française de Bagdad[279]

- Deutsche Schule Bagdad[280]

- Baghdad Japanese School (バグダッド日本人学校), a nihonjin gakko[281]

Universities

[edit]Culture

[edit]

Baghdad has always played a significant role in the broader Arab cultural sphere, contributing several significant writers, musicians and visual artists. Historically, the city had a vibrant modern culture and lifestyle.[116] Famous Arab poets and singers such as Nizar Qabbani, Umm Kulthum, Fairuz, Salah Al-Hamdani, Ilham al-Madfai and others have performed for the city. The dialect of Arabic spoken in Baghdad today differs from that of other large urban centers in Iraq, having features more characteristic of nomadic Arabic dialects (Versteegh, The Arabic Language). It is possible that this was caused by the repopulating of the city with rural residents after the multiple sackings of the late Middle Ages. For poetry written about Baghdad, see Reuven Snir (ed.), Baghdad: The City in Verse (Harvard, 2013).[282] Baghdad joined the UNESCO Creative Cities Network as a City of Literature in December 2015.[283]

Some of the important cultural institutions in the city include the National Theater, which was looted during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, but efforts are underway to restore the theater.[284] The live theater industry received a boost during the 1990s, when UN sanctions limited the import of foreign films. As many as 30 movie theaters were reported to have been converted to live stages, producing a wide range of comedies and dramatic productions.[285] Institutions offering cultural education in Baghdad include The Music and Ballet School of Baghdad and the Institute of Fine Arts Baghdad. The Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra is a government funded symphony orchestra in Baghdad. The INSO plays primarily classical European music, as well as original compositions based on Iraqi and Arab instruments and music. Mandaeans had cultural club in Al-Zawraa, where poetry evenings and cultural seminars were held, attended by poets, writers, artists, officials, and dignitaries of the communities.[286] There is also a social cultural center of Mandaeans at al-Qadisiyyah.[286] Baghdad Jewish Community Center is located in Al-Rashid Street.[287]

Baghdad is also home to a number of museums which housed artifacts and relics of ancient civilization; many of these were stolen, and the museums looted, during the widespread chaos immediately after United States forces entered the city.

During occupation of Iraq, AFN Iraq ("Freedom Radio") broadcast news and entertainment within Baghdad, among other locations. There is also a private radio station called "Dijlah" (named after the Arabic word for the Tigris River) that was created in 2004 as Iraq's first independent talk radio station. Radio Dijlah offices, in the Jamia neighborhood of Baghdad, have been attacked on several occasions.[288]

Sport

[edit]Baghdad is home to some of the most successful football (soccer) teams in Iraq, the biggest being Al-Shorta (Police), Al-Quwa Al-Jawiya (Air Force), Al-Zawraa, and Al-Talaba (Students). The largest stadium in Baghdad is Al-Shaab Stadium, which was opened in 1966. In recent years, the capital has seen the building of several football stadiums which are meant be opened in near future. The city has also had a strong tradition of horse racing ever since World War I, known to Baghdadis simply as 'Races'. There are reports of pressures by the Islamists to stop this tradition due to the associated gambling.[289]

| Club | Founded | League |

|---|---|---|

| Al-Quwa Al-Jawiya SC | 1931 | Iraq Stars League |

| Al-Shorta SC | 1932 | Iraq Stars League |

| Al-Zawraa SC | 1969 | Iraq Stars League |

| Al-Talaba SC | 1969 | Iraq Stars League |

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Petersen, Andrew (13 September 2011). "Baghdad (Madinat al-Salam)". Islamic Arts & Architecture. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ "المؤشرات الديمغرافية والسكانية - هيأة الإحصاء ونظم المعلومات الجغرافية" (in Arabic). هيأة الاحصاء ونظم المعلومات الجغرافية.

- ^ a b Ceylan, Ebubekir (2009). "Namık Paşa'nın Bağdat Valilikleri". Toplumsal Tarih (in Turkish) (186): 61.

- ^ Ceylan, Ebubekir (2011). The Ottoman Origins of Modern Iraq: Political Reform, Modernization and Development in the Nineteenth Century Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Baghdad". European Union Agency for Asylum. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Duri, A.A. (2012). "Bag̲h̲dād". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0084.

- ^ "Baghdad, Foundation and early growth". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

[...] the site located between present-day Al-Kāẓimiyyah and Al-Karkh and occupied by a Persian village called Baghdad, was selected by al-Manṣūr, the second caliph of the Abbāsid dynasty, for his capital.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (24 October 2019). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780191882913.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-188291-3.

- ^ Mackenzie, D. (1971). A concise Pahlavi Dictionary (p. 23, 16).

- ^ "BAGHDAD i. Before the Mongol Invasion – Encyclopædia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Guy Le Strange, "Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate from Contemporary Arabic and Persian", pg 10

- ^ Joneidi, F. (2007). متنهای پهلوی. In Pahlavi Script and Language (Arsacid and Sassanid) نامه پهلوانی: آموزش خط و زبان پهلوی اشکانی و ساسانی (second ed., p. 109). Tehran: Balkh (نشر بلخ).

- ^ "Persimmons surviving winter in Bagdati, Georgia". Georgian Journal. 22 February 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. BRILL. 1987. ISBN 978-90-04-08265-6. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. BRILL. 1987. pp. 564–. ISBN 978-90-04-08265-6. OCLC 1025754805. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ John Block Friedman; Kristen Mossler Figg, eds. (4 July 2013). Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-59094-9. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Brinkmann J.a. (1968). Political history of Post-Kassite Babylonia (1158-722 b. C.) (A). Pontificio Istituto Biblico. ISBN 978-88-7653-243-6. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Wall-Romana, Christophe (1990). "An Areal Location of Agade". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 49 (3): 205–245, 244. doi:10.1086/373442. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 546244. S2CID 161165836.

- ^ a b Sallaberger, Walther (1999). Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit. Aage Westenholz. Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätsverlag. p. 245. ISBN 978-3-7278-1210-1. OCLC 43521617.

- ^ Le Strange, Guy. "Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate from Contemporary Arabic and Persian Sources". Internet Archive. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Wall-Romana, Christophe (1990). "An Areal Location of Agade". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 49 (3): 234–238, 244–245. doi:10.1086/373442. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 546244. S2CID 161165836.

- ^ Sallaberger, Walther (1999). Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit. Aage Westenholz. Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätsverlag. p. 32. ISBN 978-3-7278-1210-1. OCLC 43521617.

- ^ a b Corzine, Phyllis (2005). The Islamic Empire. Thomson Gale. pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Times History of the World. London: Times Books. 2000.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 14

- ^ Wiet, Gastron (1971). Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-0922-0.

- ^ Hill, Donald R. (1994). Islamic Science and Engineering. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7486-0457-9.

- ^ Islam's Contribution to Science By Husain Muzzafar, S. Muzaffar Husain, pg. 31

- ^ "Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī (Sāriya) | ISMI". ismi.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de. Retrieved 14 April 2025.

- ^ a b Wiet 1971, p. 12.

- ^ Tillier, Mathieu (2009). Les cadis d'Iraq et l'État Abbasside (132/750-334/945). Presses de l'Ifpo. doi:10.4000/books.ifpo.673. ISBN 978-2-35159-028-7.

- ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1 January 2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2.

- ^ "سلمان الفارسي - الصحابة - موسوعة الاسرة المسلمة" (in Arabic). Islam.aljayyash.net. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, by Edward Gibbon

- ^ [1] Pedersén, Olof, "Excavated and Unexcavated Libraries in Babylon", Babylon: Wissenskultur in Orient und Okzident, edited by Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum, Margarete van Ess and Joachim Marzahn, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 47-68, 2011

- ^ Dunn 2005, p. 102; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, p. 142 Vol. 2

- ^ Zayn Kassam; Bridget Blomfield (2015), "Remembering Fatima and Zaynab: Gender in Perspective", in Farhad Daftory (ed.), The Shi'i World, I.B Tauris Press

- ^ al-Aadhamy, Waleed (2001). Elders of Time and Neighbors of Nu'man. Baghdad: al-Raqeem Library.

- ^ Battuta, pg. 75[full citation needed]

- ^ "'Soul Of Old Baghdad': City Centre Sees Timid Revival". Forbes India. Retrieved 14 April 2025.

- ^ Corzine, Phyllis (2005). The Islamic Empire. Thomson Gale. p. 69.

- ^ Wiet 1971, p. 13.

- ^ a b "Abbasid Ceramics: Plan of Baghdad". Archived from the original on 25 March 2003. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Yakut: Baghdad under the Abbasids, c. 1000CE"

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 65

- ^ a b Bobrick 2012, p. 67

- ^ Jan-Waalke Meyer, Tell Chuera: Vorberichte zu den Grabungskampagnen 1998 bis 2005, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2010 ,ISBN 978-3-447-06182-7

- ^ Helms, Tobias, and Philippe Quenet, "The Fortifiction of Circular Cities: The Examples of Tell Chuēra and Tell al-Rawda", Circular Cities of Early Bronze Age Syria, pp. 77-99, 2020

- ^ Kennedy, H. "BAGHDAD i. Before the Mongol Invasion – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2007). "Arabian Nights". In Kate Fleet; Gudrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_0021.

Arabian Nights, the work known in Arabic as Alf layla wa-layla

- ^ See:

- Hattstein, Markus; Peter Delius (2000). Islam Art and Architecture. Könemann. p. 96. ISBN 3-8290-2558-0.

- Encyclopædia Iranica, Columbia University, p.413.

- ^ الباب الوسطاني حكاية بغداد المدوّرة وأقدم مدفع عراقي Archived 23 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Narjes Magazine. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Marozzi, Justin (16 March 2016). "Story of cities #3: the birth of Baghdad was a landmark for world civilisation". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 April 2025.

- ^ "بالصور.. أبو تحسين آخر حكواتي في بغداد". الجزيرة نت (in Arabic). Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ a b Gordon, M.S. (2006). Baghdad. In Meri, J.W. ed. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b When Baghdad was centre of the scientific world Archived 14 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Historical Features of the Tigris River in Baghdad Rusafa, which extends from the school Al-Mustansiriya to the Abbasid Palace". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ Yarshater, E., ed. (1983). The Cambridge History of Iran. doi:10.1017/chol9780521200929. ISBN 978-1-139-05494-2.

The population of Hira comprised its townspeople, the 'Ibad "devotees", who were Nestorian Christians using Syriac as their liturgical and cultural language, though Arabic was probably the language of daily intercourse.

- ^ Ohlig, Karl-Heinz (2013). Early Islam – The hidden origins of Islam: new research into its early history. Prometheus Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-61614-825-6. OCLC 914334282.

The 'Ibad are tribes made up of different Arabian families that became connected with Christianity in al-Hira.

- ^ Beeston, A.F.L.; Shahîd, Irfan (2012). "al-ḤĪRA". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_sim_2891.

- ^ Meri, Josef (12 January 2018). Routledge Revivals: Medieval Islamic Civilization (2006). doi:10.4324/9781315162416. ISBN 978-1-315-16241-6.

- ^ "Sir Henry Lyons, F.R.S". Nature. 132 (3323): 55. July 1933. Bibcode:1933Natur.132S..55.. doi:10.1038/132055c0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 47244046.

- ^ Pormann, Peter E. (2007). Medieval Islamic medicine. Savage-Smith, Emilie. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-58901-160-1. OCLC 71581787.