Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Huntingtin

View on Wikipedia

Huntingtin (Htt) is a human protein encoded by the HTT gene, also known as IT15 ("interesting transcript 15").[5] Pathogenic expansions in HTT (disease-causing repeat length increases) cause Huntington's disease (HD), and the protein has also been implicated in mechanisms of long-term memory storage.[6]

HTT is expressed in many tissues, with the highest levels in the brain. Expression is developmentally regulated and required for embryogenesis.[7] Huntingtin normally consists of 3,144 amino acids and has a predicted mass of ~350 kDa, depending on the length of its polyglutamine tract. Polymorphisms in HTT alter the number of glutamine residues: the wild-type allele encodes 6–35 repeats, whereas pathogenic expansions in HD exceed 36, with severe juvenile cases reaching ~250 repeats.[8] The name huntingtin reflects this association with disease; IT15 was its earlier designation.

The molecular functions of huntingtin are not fully defined, but the protein is essential for neuronal survival and development. It is thought to contribute to intracellular signaling pathways, axonal transport, and vesicle trafficking, as well as to mediate protein–protein interactions. Huntingtin has also been shown to exert protective effects against apoptosis. Experimental disruption of HTT in model organisms results in embryonic lethality, underscoring its critical role in development.[7] Expanded polyglutamine tracts in huntingtin cause toxic gain-of-function effects leading to Huntington's disease, an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disease. The pathogenic protein aggregates in neurons, disrupting cellular processes and ultimately causing cell death.

Gene

[edit]The 5'-end (five prime end) of the HTT gene has a sequence of three DNA bases, cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG), coding for the amino acid glutamine, that is repeated multiple times. This region is called a trinucleotide repeat. The usual CAG repeat count is between seven and 35 repeats.

The HTT gene is located on the short arm (p) of chromosome 4 at position 16.3, from base pair 3,074,510 to base pair 3,243,960.[9]

Structure

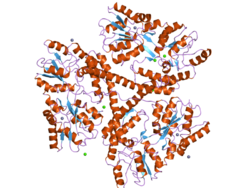

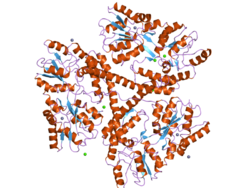

[edit]The Huntingtin (HTT) protein is a large, predominantly α-helical molecule composed of 3,144 amino acids and weighing approximately 348kDa in its canonical form. Its structure is organized into three major domains: the amino-terminal domain, the carboxy-terminal domain, and a smaller bridge domain that connects the two. Both the amino- and carboxy-terminal regions are characterized by multiple HEAT repeats (named for Huntingtin, Elongation factor 3, Protein phosphatase 2A, and lipid kinase TOR), which are arranged in a solenoid or superhelical fashion and play a crucial role in mediating protein-protein interactions. The bridge domain contains various types of tandem repeats and helps maintain the structural connection between the larger domains. The highly variable N-terminal segment of huntingtin contains the polyglutamine (polyQ) tract—expanded in Huntington's disease—which is often intrinsically disordered and not fully resolved in high-resolution structures. Huntingtin's flexible, extended architecture is stabilized when complexed with HAP40, a partner protein, allowing the protein to function as a scaffold and interaction hub in the cell.[10][11]

In recent years, multiple research groups have managed to resolve the 3D structure of full-size HTT using cryogenic electron microscopy cryoEM. This revealed the 3D architecture of the various helical HEAT repeat domains that make up the protein's native fold, as illustrated in the figure to right.[10] However, up to 25% of the protein chain was not visible in the structure, due to flexibility. This notably included the N-terminal region affected by mutations in Huntington's disease, as discussed below.

Function

[edit]The function of huntingtin (Htt) is not well understood but it is involved in axonal transport.[12] Huntingtin is essential for development, and its absence is lethal in mice.[7] The protein has no sequence homology with other proteins and is highly expressed in neurons and testes in humans and rodents.[13] Huntingtin upregulates the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) at the transcription level, but the mechanism by which huntingtin regulates gene expression has not been determined.[14] From immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and subcellular fractionation studies of the molecule, it has been found that huntingtin is primarily associated with vesicles and microtubules.[15][16] These appear to indicate a functional role in cytoskeletal anchoring or transport of mitochondria. The Htt protein is involved in vesicle trafficking as it interacts with HIP1, a clathrin-binding protein, to mediate endocytosis, the trafficking of materials into a cell.[17][18] Huntingtin has also been shown to have a role in the establishment in epithelial polarity through its interaction with RAB11A.[19]

Interactions

[edit]Huntingtin has been found to interact directly with at least 19 other proteins, of which six are used for transcription, four for transport, three for cell signalling, and six others of unknown function (HIP5, HIP11, HIP13, HIP15, HIP16, and CGI-125).[20] Over 100 interacting proteins have been found, such as huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) and huntingtin interacting protein 1 (HIP1), these were typically found using two-hybrid screening and confirmed using immunoprecipitation.[21][22]

| Interacting Protein | PolyQ length dependence | Function |

|---|---|---|

| α-adaptin C/HYPJ | Yes | Endocytosis |

| Akt/PKB | No | Kinase |

| CBP | Yes | Transcriptional co-activator with acetyltransferase activity |

| CA150 | No | Transcriptional activator |

| CIP4 | Yes | cdc42-dependent signal transduction |

| CtBP | Yes | Transcription factor |

| FIP2 | Not known | Cell morphogenesis |

| Grb2[23] | Not known | Growth factor receptor binding protein |

| HAP1 | Yes | Membrane trafficking |

| HAP40 (F8A1, F8A2, F8A3) | Not known | Unknown |

| HIP1 | Yes | Endocytosis, proapoptotic |

| HIP14/HYP-H | Yes | Trafficking, endocytosis |

| N-CoR | Yes | Nuclear receptor co-repressor |

| NF-κB | Not known | Transcription factor |

| p53[24] | No | Transcription factor |

| PACSIN1[25] | Yes | Endocytosis, actin cytoskeleton |

| DLG4 (PSD-95) | Yes | Postsynaptic Density 95 |

| RASA1 (RasGAP)[23] | Not known | Ras GTPase activating protein |

| SH3GL3[26] | Yes | Endocytosis |

| SIN3A | Yes | Transcriptional repressor |

| Sp1[27] | Yes | Transcription factor |

Huntingtin has also been shown to interact with:

Clinical significance

[edit]Huntington's disease

[edit]| Repeat count | Classification | Disease status |

|---|---|---|

| <26 | Normal | Unaffected |

| 27–35 | Intermediate | Unaffected |

| 36–40 | Reduced penetrance | +/- Affected |

| >40 | Full penetrance | Affected |

Huntington's disease (HD) is caused by a mutated form of the huntingtin gene, where excessive (more than 36) CAG repeats result in formation of an unstable protein.[34] These expanded repeats lead to production of a huntingtin protein that contains an abnormally long polyglutamine tract at the N-terminus. This makes it part of a class of neurodegenerative disorders known as trinucleotide repeat disorders or polyglutamine disorders. The key sequence which is found in Huntington's disease is a trinucleotide repeat expansion of glutamine residues beginning at the 18th amino acid. In unaffected individuals, this contains between 9 and 35 glutamine residues with no adverse effects.[5] However, 36 or more residues produce an erroneous mutant form of Htt, (mHtt). Reduced penetrance is found in counts 36–39.[35]

N-terminal fragments of mHtt have been discovered in Huntington's disease patients. These fragments can be generated by protease enzymes that cut this elongated protein into fragments. Moreover, recent research has identified aberrant splicing to affect the mutant gene products, yielding fragments that coincide with the first exon of the protein.[36] These protein fragments are observed to form abnormal clumps, known as neuronal intranuclear inclusions (NIIs), inside nerve cells, and may attract other, normal proteins into the clumps. The characteristic presence of these clumps in patients was thought to contribute to the development of Huntington disease.[37] However, later research raised questions about the role of the inclusions (clumps) by showing the presence of visible NIIs extended the life of neurons and acted to reduce intracellular mutant huntingtin in neighboring neurons.[38] One confounding factor is that different types of aggregates are now recognised to be formed by the mutant protein, including protein deposits that are too small to be recognised as visible deposits in the above-mentioned studies.[39] The likelihood of neuronal death remains difficult to predict. Likely multiple factors are important, including: (1) the length of CAG repeats in the huntingtin gene and (2) the neuron's exposure to diffuse intracellular mutant huntingtin protein. NIIs (protein clumping) can be helpful as a coping mechanism—and not simply a pathogenic mechanism—to stem neuronal death by decreasing the amount of diffuse huntingtin.[40] This process is particularly likely to occur in the striatum (a part of the brain that coordinates movement) primarily, and the frontal cortex (a part of the brain that controls thinking and emotions). Further, it is possible the pathogenic mechanism lay more with the RNA transcripts and their potential CAG repeats to exhibit RNAi than with the actual huntingtin protein itself.[41]

People with 36 to 40 CAG repeats may or may not develop the signs and symptoms of Huntington disease, while people with more than 40 repeats will develop the disorder during a normal lifetime. When there are more than 60 CAG repeats, the person develops a severe form of HD known as juvenile HD. Therefore, the number of CAG (the sequence coding for the amino acid glutamine) repeats influences the age of onset of the disease. No case of HD has been diagnosed with a count less than 36.[35]

As the altered gene is passed from one generation to the next, the size of the CAG repeat expansion can change; it often increases in size, especially when it is inherited from the father. People with 28 to 35 CAG repeats have not been reported to develop the disorder, but their children are at risk of having the disease if the repeat expansion increases.

In the pathogenesis of the disease, there is further somatic expansion of CAG repeats. It takes decades to reach 80 repeats, then years to reach 150 repeats. Beyond 150, cellular toxicity start to manifest. Over months, the neuron slowly loses its cell identity until cell death pathways are activated.[42]

Mitochondrial dysfunction

[edit]Huntingtin is a scaffolding protein in the ATM oxidative DNA damage response complex. Mutant huntingtin (mHtt) plays a key role in mitochondrial dysfunction involving the inhibition of mitochondrial electron transport, inhibition of mitochondrial import processes, higher levels of reactive oxygen species and increased oxidative stress.[43][44] The promotion of oxidative damage to DNA may contribute to Huntington's disease pathology.[45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000197386 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029104 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group (Mar 1993). "A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group". Cell. 72 (6): 971–983. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-E. hdl:2027.42/30901. PMID 8458085. S2CID 802885.

- ^ Choi YB, Kadakkuzha BM, Liu XA, Akhmedov K, Kandel ER, Puthanveettil SV (July 23, 2014). "Huntingtin is critical both pre- and postsynaptically for long-term learning-related synaptic plasticity in Aplysia". PLOS ONE. 9 (7) e103004. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j3004C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103004. PMC 4108396. PMID 25054562.

- ^ a b c Nasir J, Floresco SB, O'Kusky JR, Diewert VM, Richman JM, Zeisler J, et al. (Jun 1995). "Targeted disruption of the Huntington's disease gene results in embryonic lethality and behavioral and morphological changes in heterozygotes". Cell. 81 (5): 811–823. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90542-1. PMID 7774020. S2CID 16835259.

- ^ Nance MA, Mathias-Hagen V, Breningstall G, Wick MJ, McGlennen RC (Jan 1999). "Analysis of a very large trinucleotide repeat in a patient with juvenile Huntington's disease". Neurology. 52 (2): 392–394. doi:10.1212/wnl.52.2.392. PMID 9932964. S2CID 33091017.

- ^ "HTT gene". Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ^ a b Guo Q, Huang B, Cheng J, Seefelder M, Engler T, Pfeifer G, et al. (Mar 2018). "The cryo-electron microscopy structure of huntingtin". Nature. 555 (7694): 117–120. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..117G. doi:10.1038/nature25502. PMC 5837020. PMID 29466333.

- ^ Truant R, Harding RJ, Neuman K, Maiuri T (November 2024). "Revisiting huntingtin activity and localization signals in the context of protein structure". Journal of Huntington's Disease. 13 (4): 419–430. doi:10.1177/18796397241295303. PMID 39973382.

- ^ Vitet H, Brandt V, Saudou F (August 2020). "Traffic signaling: new functions of huntingtin and axonal transport in neurological disease". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 63: 122–130. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2020.04.001. PMID 32408142. S2CID 218596089.

- ^ Cattaneo E, Zuccato C, Tartari M (December 2005). "Normal huntingtin function: an alternative approach to Huntington's disease". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 6 (12): 919–930. doi:10.1038/nrn1806. PMID 16288298. S2CID 10119487.

- ^ Zuccato C, Ciammola A, Rigamonti D, Leavitt BR, Goffredo D, Conti L, et al. (July 2001). "Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington's disease". Science. 293 (5529). New York, N.Y.: 493–498. doi:10.1126/science.1059581. PMID 11408619. S2CID 20703272.

- ^ Hoffner G, Kahlem P, Djian P (March 2002). "Perinuclear localization of huntingtin as a consequence of its binding to microtubules through an interaction with beta-tubulin: relevance to Huntington's disease". Journal of Cell Science. 115 (Pt 5): 941–948. doi:10.1242/jcs.115.5.941. PMID 11870213.

- ^ DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase K, Schwarz C, Meloni A, Young C, et al. (May 1995). "Huntingtin is a cytoplasmic protein associated with vesicles in human and rat brain neurons". Neuron. 14 (5): 1075–1081. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(95)90346-1. PMID 7748555. S2CID 18071283.

- ^ Velier J, Kim M, Schwarz C, Kim TW, Sapp E, Chase K, et al. (July 1998). "Wild-type and mutant huntingtins function in vesicle trafficking in the secretory and endocytic pathways". Experimental Neurology. 152 (1): 34–40. doi:10.1006/exnr.1998.6832. PMID 9682010. S2CID 36726422.

- ^ Waelter S, Scherzinger E, Hasenbank R, Nordhoff E, Lurz R, Goehler H, et al. (August 2001). "The huntingtin interacting protein HIP1 is a clathrin and alpha-adaptin-binding protein involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis". Human Molecular Genetics. 10 (17): 1807–1817. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.17.1807. PMID 11532990.

- ^ Elias S, McGuire JR, Yu H, Humbert S (May 2015). "Huntingtin Is Required for Epithelial Polarity through RAB11A-Mediated Apical Trafficking of PAR3-aPKC". PLOS Biology. 13 (5) e1002142. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002142. PMC 4420272. PMID 25942483.

- ^ Harjes P, Wanker EE (Aug 2003). "The hunt for huntingtin function: interaction partners tell many different stories". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 28 (8): 425–433. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00168-3. PMID 12932731.

- ^ Goehler H, Lalowski M, Stelzl U, Waelter S, Stroedicke M, Worm U, et al. (Sep 2004). "A protein interaction network links GIT1, an enhancer of huntingtin aggregation, to Huntington's disease". Molecular Cell. 15 (6): 853–865. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.016. PMID 15383276.

- ^ Wanker EE, Rovira C, Scherzinger E, Hasenbank R, Wälter S, Tait D, et al. (Mar 1997). "HIP-I: a huntingtin interacting protein isolated by the yeast two-hybrid system". Human Molecular Genetics. 6 (3): 487–495. doi:10.1093/hmg/6.3.487. PMID 9147654.

- ^ a b Liu YF, Deth RC, Devys D (Mar 1997). "SH3 domain-dependent association of huntingtin with epidermal growth factor receptor signaling complexes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (13): 8121–8124. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.13.8121. PMID 9079622.

- ^ Steffan JS, Kazantsev A, Spasic-Boskovic O, Greenwald M, Zhu YZ, Gohler H, et al. (Jun 2000). "The Huntington's disease protein interacts with p53 and CREB-binding protein and represses transcription". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (12): 6763–6768. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.6763S. doi:10.1073/pnas.100110097. PMC 18731. PMID 10823891.

- ^ Modregger J, DiProspero NA, Charles V, Tagle DA, Plomann M (Oct 2002). "PACSIN 1 interacts with huntingtin and is absent from synaptic varicosities in presymptomatic Huntington's disease brains". Human Molecular Genetics. 11 (21): 2547–2558. doi:10.1093/hmg/11.21.2547. PMID 12354780.

- ^ Sittler A, Wälter S, Wedemeyer N, Hasenbank R, Scherzinger E, Eickhoff H, et al. (Oct 1998). "SH3GL3 associates with the Huntingtin exon 1 protein and promotes the formation of polygln-containing protein aggregates". Molecular Cell. 2 (4): 427–436. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80142-2. PMID 9809064.

- ^ Li SH, Cheng AL, Zhou H, Lam S, Rao M, Li H, et al. (Mar 2002). "Interaction of Huntington disease protein with transcriptional activator Sp1". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (5): 1277–1287. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.5.1277-1287.2002. PMC 134707. PMID 11839795.

- ^ Kalchman MA, Graham RK, Xia G, Koide HB, Hodgson JG, Graham KC, et al. (Aug 1996). "Huntingtin is ubiquitinated and interacts with a specific ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (32): 19385–19394. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.32.19385. PMID 8702625.

- ^ Liu YF, Dorow D, Marshall J (Jun 2000). "Activation of MLK2-mediated signaling cascades by polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (25): 19035–19040. doi:10.1074/jbc.C000180200. PMID 10801775.

- ^ Hattula K, Peränen J (2000). "FIP-2, a coiled-coil protein, links Huntingtin to Rab8 and modulates cellular morphogenesis". Current Biology. 10 (24): 1603–1606. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.1603H. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00864-2. PMID 11137014. S2CID 12836037.

- ^ a b c Faber PW, Barnes GT, Srinidhi J, Chen J, Gusella JF, MacDonald ME (Sep 1998). "Huntingtin interacts with a family of WW domain proteins". Human Molecular Genetics. 7 (9): 1463–1474. doi:10.1093/hmg/7.9.1463. PMID 9700202.

- ^ Holbert S, Dedeoglu A, Humbert S, Saudou F, Ferrante RJ, Néri C (Mar 2003). "Cdc42-interacting protein 4 binds to huntingtin: neuropathologic and biological evidence for a role in Huntington's disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (5): 2712–2717. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.2712H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0437967100. PMC 151406. PMID 12604778.

- ^ Singaraja RR, Hadano S, Metzler M, Givan S, Wellington CL, Warby S, et al. (Nov 2002). "HIP14, a novel ankyrin domain-containing protein, links huntingtin to intracellular trafficking and endocytosis". Human Molecular Genetics. 11 (23): 2815–2828. doi:10.1093/hmg/11.23.2815. PMID 12393793.

- ^ a b Walker FO (Jan 2007). "Huntington's disease". Lancet. 369 (9557). London, England: 218–228. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. PMID 17240289. S2CID 46151626.

- ^ a b Chong SS, Almqvist E, Telenius H, LaTray L, Nichol K, Bourdelat-Parks B, et al. (Feb 1997). "Contribution of DNA sequence and CAG size to mutation frequencies of intermediate alleles for Huntington disease: evidence from single sperm analyses". Human Molecular Genetics. 6 (2): 301–309. doi:10.1093/hmg/6.2.301. PMID 9063751.

- ^ Sathasivam K, Neueder A, Gipson TA, Landles C, Benjamin AC, Bondulich MK, et al. (Feb 2013). "Aberrant splicing of HTT generates the pathogenic exon 1 protein in Huntington disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (6): 2366–2370. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.2366S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221891110. hdl:1721.1/79814. PMC 3568346. PMID 23341618.

- ^ Davies SW, Turmaine M, Cozens BA, DiFiglia M, Sharp AH, Ross CA, et al. (Aug 1997). "Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation". Cell. 90 (3): 537–548. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80513-9. PMID 9267033. S2CID 549691.

- ^ Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S (Oct 2004). "Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death". Nature. 431 (7010): 805–810. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..805A. doi:10.1038/nature02998. PMID 15483602.

- ^ Sahl SJ, Lau L, Vonk WI, Weiss LE, Frydman J, Moerner WE (2016). "Delayed Emergence of Subdiffraction-Sized Mutant Huntingtin Fibrils Following Inclusion Body Formation". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 49 e2. doi:10.1017/S0033583515000219. PMC 4785097. PMID 26350150.

- ^ Orr HT (Oct 2004). "Neurodegenerative disease: neuron protection agency". Nature. 431 (7010): 747–748. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..747O. doi:10.1038/431747a. PMID 15483586. S2CID 285829.

- ^ Murmann AE, Patel M, Jeong SY, Bartom ET, Jennifer Morton A, Peter ME (2022). "The length of uninterrupted CAG repeats in stem regions of repeat disease associated hairpins determines the amount of short CAG oligonucleotides that are toxic to cells through RNA interference". Cell Death & Disease. 13 (12) 1078. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-05494-1. PMC 9803637. PMID 36585400.

- ^ Handsaker RE, Kashin S, Reed NM, Tan S, Lee WS, McDonald TM, et al. (February 2025). "Long somatic DNA-repeat expansion drives neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease". Cell. 188 (3): 623–639.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.11.038. PMC 11822645. PMID 39824182.

- ^ Liu Z, Zhou T, Ziegler AC, Dimitrion P, Zuo L (2017). "Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2017 2525967. doi:10.1155/2017/2525967. PMC 5529664. PMID 28785371.

- ^ Maiuri T, Mocle AJ, Hung CL, Xia J, van Roon-Mom WM, Truant R (25 December 2016). "Huntingtin is a scaffolding protein in the ATM oxidative DNA damage response complex". Human Molecular Genetics. 26 (2): 395–406. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddw395. PMID 28017939.

- ^ Ayala-Peña S (September 2013). "Role of oxidative DNA damage in mitochondrial dysfunction and Huntington's disease pathogenesis". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 62: 102–110. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.017. PMC 3722255. PMID 23602907.

Further reading

[edit]- Kosinski CM, Schlangen C, Gellerich FN, Gizatullina Z, Deschauer M, Schiefer J, et al. (August 2007). "Myopathy as a first symptom of Huntington's disease in a Marathon runner". Movement Disorders. 22 (11): 1637–1640. doi:10.1002/mds.21550. PMID 17534945. S2CID 30904037.

- Bates G (May 2003). "Huntingtin aggregation and toxicity in Huntington's disease". Lancet. 361 (9369). London, England: 1642–1644. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13304-1. PMID 12747895. S2CID 7587406.

- Cattaneo E (Feb 2003). "Dysfunction of wild-type huntingtin in Huntington disease". News in Physiological Sciences. 18: 34–37. doi:10.1152/nips.01410.2002. PMID 12531930.

- Gárdián G, Vécsei L (Oct 2004). "Huntington's disease: pathomechanism and therapeutic perspectives". Journal of Neural Transmission. 111 (10–11). Vienna, Austria: 1485–1494. doi:10.1007/s00702-004-0201-4. PMID 15480847. S2CID 2961376.

- Landles C, Bates GP (Oct 2004). "Huntingtin and the molecular pathogenesis of Huntington's disease. Fourth in molecular medicine review series". EMBO Reports. 5 (10): 958–963. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400250. PMC 1299150. PMID 15459747.

- Jones AL (Jun 1999). "The localization and interactions of huntingtin". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 354 (1386): 1021–1027. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0454. PMC 1692601. PMID 10434301.

- Li SH, Li XJ (Oct 2004). "Huntingtin and its role in neuronal degeneration". The Neuroscientist. 10 (5): 467–475. doi:10.1177/1073858404266777. PMID 15359012. S2CID 19491573.

- MacDonald ME, Novelletto A, Lin C, Tagle D, Barnes G, Bates G, et al. (May 1992). "The Huntington's disease candidate region exhibits many different haplotypes". Nature Genetics. 1 (2): 99–103. doi:10.1038/ng0592-99. PMID 1302016. S2CID 25472459.

- MacDonald ME (Nov 2003). "Huntingtin: alive and well and working in middle management". Science's STKE. 2003 (207) pe48. doi:10.1126/stke.2003.207.pe48. PMID 14600292. S2CID 35318234.

- Myers RH (Apr 2004). "Huntington's disease genetics". NeuroRx. 1 (2): 255–262. doi:10.1602/neurorx.1.2.255. PMC 534940. PMID 15717026.

- Rangone H, Humbert S, Saudou F (Jul 2004). "Huntington's disease: how does huntingtin, an anti-apoptotic protein, become toxic?". Pathologie-Biologie. 52 (6): 338–342. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2003.06.004. PMID 15261377.

- Young AB (Feb 2003). "Huntingtin in health and disease". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 111 (3): 299–302. doi:10.1172/JCI17742. PMC 151871. PMID 12569151.

External links

[edit]- Huntingtin+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- The Huntingtin Protein and Protein Aggregation at HOPES Archived 2021-02-12 at the Wayback Machine: Huntington's Outreach Project for Education at Stanford

- The HDA Huntington's Disease Association UK

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 143100

- EntrezGene 3064

- GeneCard

- iHOP