Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neuron

View on Wikipedia| Neuron | |

|---|---|

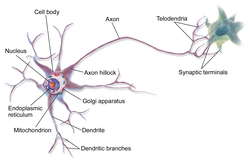

Anatomy of a multipolar neuron | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D009474 |

| NeuroLex ID | sao1417703748 |

| TA98 | A14.0.00.002 |

| TH | H2.00.06.1.00002 |

| FMA | 54527 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

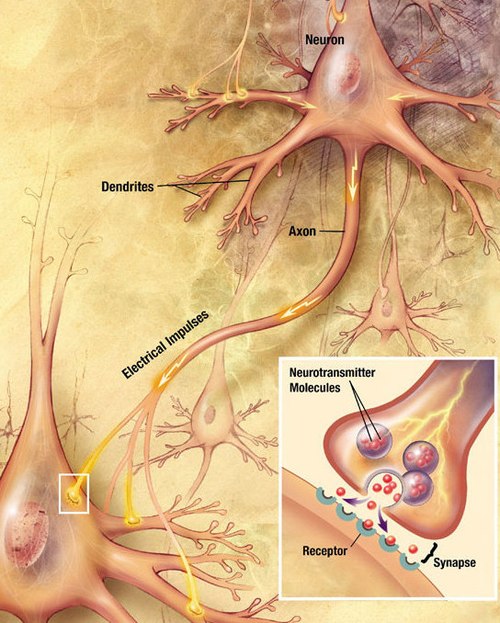

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English),[1] or nerve cell, is an excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network in the nervous system. They are located in the nervous system and help to receive and conduct impulses. Neurons communicate with other cells via synapses, which are specialized connections that commonly use minute amounts of chemical neurotransmitters to pass the electric signal from the presynaptic neuron to the target cell through the synaptic gap.

Neurons are the main components of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoans. Plants and fungi do not have nerve cells. Molecular evidence suggests that the ability to generate electric signals first appeared in evolution some 700 to 800 million years ago, during the Tonian period. Predecessors of neurons were the peptidergic secretory cells. They eventually gained new gene modules which enabled cells to create post-synaptic scaffolds and ion channels that generate fast electrical signals. The ability to generate electric signals was a key innovation in the evolution of the nervous system.[2]

Neurons are typically classified into three types based on their function. Sensory neurons respond to stimuli such as touch, sound, or light that affect the cells of the sensory organs, and they send signals to the spinal cord and then to the sensorial area in the brain. Motor neurons receive signals from the brain and spinal cord to control everything from muscle contractions[3] to glandular output. Interneurons connect neurons to other neurons within the same region of the brain or spinal cord. When multiple neurons are functionally connected together, they form what is called a neural circuit.

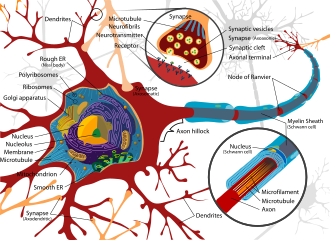

A neuron contains all the structures of other cells such as a nucleus, mitochondria, and Golgi bodies but has additional unique structures such as an axon, and dendrites.[4] The soma or cell body, is a compact structure, and the axon and dendrites are filaments extruding from the soma. Dendrites typically branch profusely and extend a few hundred micrometers from the soma. The axon leaves the soma at a swelling called the axon hillock and travels for as far as 1 meter in humans or more in other species. It branches but usually maintains a constant diameter. At the farthest tip of the axon's branches are axon terminals, where the neuron can transmit a signal across the synapse to another cell. Neurons may lack dendrites or have no axons. The term neurite is used to describe either a dendrite or an axon, particularly when the cell is undifferentiated.

Most neurons receive signals via the dendrites and soma and send out signals down the axon. At the majority of synapses, signals cross from the axon of one neuron to the dendrite of another. However, synapses can connect an axon to another axon or a dendrite to another dendrite. The signaling process is partly electrical and partly chemical. Neurons are electrically excitable, due to the maintenance of voltage gradients across their membranes. If the voltage changes by a large enough amount over a short interval, the neuron generates an all-or-nothing electrochemical pulse called an action potential. This potential travels rapidly along the axon and activates synaptic connections as it reaches them. Synaptic signals may be excitatory or inhibitory, increasing or reducing the net voltage that reaches the soma.

In most cases, neurons are generated by neural stem cells during brain development and childhood. Neurogenesis largely ceases during adulthood in most areas of the brain.

Nervous system

[edit]Neurons are the primary components of the nervous system, along with the glial cells that give them structural and metabolic support.[5] The nervous system is made up of the central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system, which includes the autonomic, enteric and somatic nervous systems.[6] In vertebrates, the majority of neurons belong to the central nervous system, but some reside in peripheral ganglia, and many sensory neurons are situated in sensory organs such as the retina and cochlea.

Axons may bundle into nerve fascicles that make up the nerves in the peripheral nervous system (like strands of wire that make up a cable). In the central nervous system bundles of axons are called nerve tracts.

Anatomy and histology

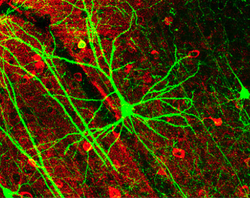

[edit]Neurons are highly specialized for the processing and transmission of cellular signals. Given the diversity of functions performed in different parts of the nervous system, there is a wide variety in their shape, size, and electrochemical properties. For instance, the soma of a neuron can vary from 4 to 100 micrometers in diameter.[7]

- The soma is the body of the neuron. As it contains the nucleus, most protein synthesis occurs here. The nucleus can range from 3 to 18 micrometers in diameter.[8]

- The dendrites of a neuron are cellular extensions with many branches. This overall shape and structure are referred to metaphorically as a dendritic tree. The branches form fractal patterns that repeat at multiple size scales.[9] This fractal tree is where the majority of input to the neuron occurs via the dendritic spine.

- The axon is a finer, cable-like projection that can extend tens, hundreds, or even tens of thousands of times the diameter of the soma in length. The axon primarily carries nerve signals away from the soma and carries some types of information back to it. Many neurons have only one axon, but this axon may—and usually will—undergo extensive branching, enabling communication with many target cells. The part of the axon where it emerges from the soma is called the axon hillock. Besides being an anatomical structure, the axon hillock also has the greatest density of voltage-dependent sodium channels. This makes it the most easily excited part of the neuron and the spike initiation zone for the axon. In electrophysiological terms, it has the most negative threshold potential.

- While the axon and axon hillock are generally involved in information outflow, this region can also receive input from other neurons.

- The axon terminal is found at the end of the axon farthest from the soma and contains synapses. Synaptic boutons are specialized structures where neurotransmitter chemicals are released to communicate with target neurons. In addition to synaptic boutons at the axon terminal, a neuron may have en passant boutons, which are located along the length of the axon.

The accepted view of the neuron attributes dedicated functions to its various anatomical components; however, dendrites and axons often act in ways contrary to their so-called main function.[10]

Axons and dendrites in the central nervous system are typically only about one micrometer thick, while some in the peripheral nervous system are much thicker. The soma is usually about 10–25 micrometers in diameter and often is not much larger than the cell nucleus it contains. The longest axon of a human motor neuron can be over a meter long, reaching from the base of the spine to the toes.

Sensory neurons can have axons that run from the toes to the posterior column of the spinal cord, over 1.5 meters in adults. Giraffes have single axons several meters in length running along the entire length of their necks. Much of what is known about axonal function comes from studying the squid giant axon, an ideal experimental preparation because of its relatively immense size (0.5–1 millimeter thick, several centimeters long).

Fully differentiated neurons are permanently postmitotic[11] however, stem cells present in the adult brain may regenerate functional neurons throughout the life of an organism (see neurogenesis). Astrocytes are star-shaped glial cells that have been observed to turn into neurons by virtue of their stem cell-like characteristic of pluripotency.[12]

Membrane

[edit]Like all animal cells, the cell body of every neuron is enclosed by a plasma membrane, a bilayer of lipid molecules with many types of embedded protein structures.[13] A lipid bilayer is a powerful electrical insulator, but in neurons, many of the protein structures embedded in the membrane are electrically active. These include ion channels that permit electrically charged ions to flow across the membrane and ion pumps that chemically transport ions from one side of the membrane to the other. Most ion channels are gated, permeable only to specific types of ions. Some ion channels are voltage gated, meaning that they can be switched between open and closed states by altering the voltage difference across the membrane. Others are chemically gated, meaning that they can be switched between open and closed states by interactions with chemicals that diffuse through the extracellular fluid. The ions include sodium, potassium, chloride, and calcium. The interactions between ion channels and ion pumps produce a voltage difference across the membrane, typically a little less than 1/10 of a volt at baseline. This voltage has two functions: first, it provides a power source for an assortment of voltage-dependent protein machineries that are embedded in the membrane; second, it provides a basis for electrical signal transmission between different parts of the membrane.

Histology and internal structure

[edit]

Numerous microscopic clumps called Nissl bodies (or Nissl substance) are seen when nerve cell bodies are stained with a basophilic ("base-loving") dye. These structures consist of rough endoplasmic reticulum and associated ribosomal RNA. Named after German psychiatrist and neuropathologist Franz Nissl (1860–1919), they are involved in protein synthesis and their prominence can be explained by the fact that nerve cells are very metabolically active. Basophilic dyes such as aniline or (weakly) hematoxylin[14] highlight negatively charged components, and so bind to the phosphate backbone of the ribosomal RNA.

The cell body of a neuron is supported by a complex mesh of structural proteins called neurofilaments, which together with neurotubules (neuronal microtubules) are assembled into larger neurofibrils.[15] Some neurons also contain pigment granules, such as neuromelanin (a brownish-black pigment that is byproduct of synthesis of catecholamines), and lipofuscin (a yellowish-brown pigment), both of which accumulate with age.[16][17][18] Other structural proteins that are important for neuronal function are actin and the tubulin of microtubules. Class III β-tubulin is found almost exclusively in neurons. Actin is predominately found at the tips of axons and dendrites during neuronal development. There the actin dynamics can be modulated via an interplay with microtubule.[19]

There are different internal structural characteristics between axons and dendrites. Typical axons seldom contain ribosomes, except some in the initial segment. Dendrites contain granular endoplasmic reticulum or ribosomes, in diminishing amounts as the distance from the cell body increases.

Classification

[edit]

Neurons vary in shape and size and can be classified by their morphology and function.[21] The anatomist Camillo Golgi grouped neurons into two types; type I with long axons used to move signals over long distances and type II with short axons, which can often be confused with dendrites. Type I cells can be further classified by the location of the soma. The basic morphology of type I neurons, represented by spinal motor neurons, consists of a cell body called the soma and a long thin axon covered by a myelin sheath. The dendritic tree wraps around the cell body and receives signals from other neurons. The end of the axon has branching axon terminals that release neurotransmitters into a gap called the synaptic cleft between the terminals and the dendrites of the next neuron.[citation needed]

Structural classification

[edit]Polarity

[edit]

Most neurons can be anatomically characterized as:[4]

- Unipolar: single process. Unipolar cells are exclusively sensory neurons. Their dendrites receive sensory information, sometimes directly from the stimulus itself. The cell bodies of unipolar neurons are always found in ganglia. Sensory reception is a peripheral function, so the cell body is in the periphery, though closer to the CNS in a ganglion. The axon projects from the dendrite endings, past the cell body in a ganglion, and into the central nervous system.

- Bipolar: 1 axon and 1 dendrite. They are found mainly in the olfactory epithelium, and as part of the retina.

- Multipolar: 1 axon and 2 or more dendrites

- Anaxonic: where the axon cannot be distinguished from the dendrite(s)

- Pseudounipolar: 1 process which then serves as both an axon and a dendrite

Other

[edit]Some unique neuronal types can be identified according to their location in the nervous system and distinct shape. Some examples are:[citation needed]

- Basket cells, interneurons that form a dense plexus of terminals around the soma of target cells, found in the cortex and cerebellum

- Betz cells, large motor neurons in primary motor cortex

- Lugaro cells, interneurons of the cerebellum

- Medium spiny neurons, most neurons in the corpus striatum

- Purkinje cells, huge neurons in the cerebellum, a type of Golgi I multipolar neuron

- Pyramidal cells, neurons with triangular soma, a type of Golgi I

- Rosehip cells, unique human inhibitory neurons that interconnect with Pyramidal cells

- Renshaw cells, neurons with both ends linked to alpha motor neurons

- Unipolar brush cells, interneurons with unique dendrite ending in a brush-like tuft

- Granule cells, a type of Golgi II neuron

- Anterior horn cells, motoneurons located in the spinal cord

- Spindle cells, interneurons that connect widely separated areas of the brain

Functional classification

[edit]Direction

[edit]- Afferent neurons convey information from tissues and organs into the central nervous system and are also called sensory neurons.

- Efferent neurons (motor neurons) transmit signals from the central nervous system to the effector cells.

- Interneurons connect neurons within specific regions of the central nervous system.

Afferent and efferent also refer generally to neurons that, respectively, bring information to or send information from the brain.

Action on other neurons

[edit]A neuron affects other neurons by releasing a neurotransmitter that binds to chemical receptors. The effect on the postsynaptic neuron is determined by the type of receptor that is activated, not by the presynaptic neuron or by the neurotransmitter. Receptors are classified broadly as excitatory (causing an increase in firing rate), inhibitory (causing a decrease in firing rate), or modulatory (causing long-lasting effects not directly related to firing rate).[citation needed]

The two most common (90%+) neurotransmitters in the brain, glutamate and GABA, have largely consistent actions. Glutamate acts on several types of receptors and has effects that are excitatory at ionotropic receptors and a modulatory effect at metabotropic receptors. Similarly, GABA acts on several types of receptors, but all of them have inhibitory effects (in adult animals, at least). Because of this consistency, it is common for neuroscientists to refer to cells that release glutamate as "excitatory neurons", and cells that release GABA as "inhibitory neurons". Some other types of neurons have consistent effects, for example, "excitatory" motor neurons in the spinal cord that release acetylcholine, and "inhibitory" spinal neurons that release glycine.[citation needed]

The distinction between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters is not absolute. Rather, it depends on the class of chemical receptors present on the postsynaptic neuron. In principle, a single neuron, releasing a single neurotransmitter, can have excitatory effects on some targets, inhibitory effects on others, and modulatory effects on others still. For example, photoreceptor cells in the retina constantly release the neurotransmitter glutamate in the absence of light. So-called OFF bipolar cells are, like most neurons, excited by the released glutamate. However, neighboring target neurons called ON bipolar cells are instead inhibited by glutamate, because they lack typical ionotropic glutamate receptors and instead express a class of inhibitory metabotropic glutamate receptors.[22] When light is present, the photoreceptors cease releasing glutamate, which relieves the ON bipolar cells from inhibition, activating them; this simultaneously removes the excitation from the OFF bipolar cells, silencing them.[citation needed]

It is possible to identify the type of inhibitory effect a presynaptic neuron will have on a postsynaptic neuron, based on the proteins the presynaptic neuron expresses. Parvalbumin-expressing neurons typically dampen the output signal of the postsynaptic neuron in the visual cortex, whereas somatostatin-expressing neurons typically block dendritic inputs to the postsynaptic neuron.[23]

Discharge patterns

[edit]Neurons have intrinsic electroresponsive properties like intrinsic transmembrane voltage oscillatory patterns.[24] So neurons can be classified according to their electrophysiological characteristics:

- Tonic or regular spiking. Some neurons are typically constantly (tonically) active, typically firing at a constant frequency. Example: interneurons in neurostriatum.

- Phasic or bursting. Neurons that fire in bursts are called phasic.

- Fast-spiking. Some neurons are notable for their high firing rates, for example, some types of cortical inhibitory interneurons, cells in globus pallidus, retinal ganglion cells.[25][26]

Neurotransmitter

[edit]

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers passed from one neuron to another neuron or to a muscle cell or gland cell.

- Cholinergic neurons – acetylcholine. Acetylcholine is released from presynaptic neurons into the synaptic cleft. It acts as a ligand for both ligand-gated ion channels and metabotropic (GPCRs) muscarinic receptors. Nicotinic receptors are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels composed of alpha and beta subunits that bind nicotine. Ligand binding opens the channel causing the influx of Na+ depolarization and increases the probability of presynaptic neurotransmitter release. Acetylcholine is synthesized from choline and acetyl coenzyme A.

- Adrenergic neurons – noradrenaline. Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) is released from most postganglionic neurons in the sympathetic nervous system onto two sets of GPCRs: alpha adrenoceptors and beta adrenoceptors. Noradrenaline is one of the three common catecholamine neurotransmitters, and the most prevalent of them in the peripheral nervous system; as with other catecholamines, it is synthesized from tyrosine.

- GABAergic neurons – gamma aminobutyric acid. GABA is one of two neuroinhibitors in the central nervous system (CNS), along with glycine. GABA has a homologous function to ACh, gating anion channels that allow Cl− ions to enter the post synaptic neuron. Cl− causes hyperpolarization within the neuron, decreasing the probability of an action potential firing as the voltage becomes more negative (for an action potential to fire, a positive voltage threshold must be reached). GABA is synthesized from glutamate neurotransmitters by the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase.

- Glutamatergic neurons – glutamate. Glutamate is one of two primary excitatory amino acid neurotransmitters, along with aspartate. Glutamate receptors are one of four categories, three of which are ligand-gated ion channels and one of which is a G-protein coupled receptor (often referred to as GPCR).

- AMPA and Kainate receptors function as cation channels permeable to Na+ cation channels mediating fast excitatory synaptic transmission.

- NMDA receptors are another cation channel that is more permeable to Ca2+. The function of NMDA receptors depends on glycine receptor binding as a co-agonist within the channel pore. NMDA receptors do not function without both ligands present.

- Metabotropic receptors, GPCRs modulate synaptic transmission and postsynaptic excitability.

- Glutamate can cause excitotoxicity when blood flow to the brain is interrupted, resulting in brain damage. When blood flow is suppressed, glutamate is released from presynaptic neurons, causing greater NMDA and AMPA receptor activation than normal outside of stress conditions, leading to elevated Ca2+ and Na+ entering the post synaptic neuron and cell damage. Glutamate is synthesized from the amino acid glutamine by the enzyme glutamate synthase.

- Dopaminergic neurons—dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that acts on D1 type (D1 and D5) Gs-coupled receptors, which increase cAMP and PKA, and D2 type (D2, D3, and D4) receptors, which activate Gi-coupled receptors that decrease cAMP and PKA. Dopamine is connected to mood and behavior and modulates both pre- and post-synaptic neurotransmission. Loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra has been linked to Parkinson's disease. Dopamine is synthesized from the amino acid tyrosine. Tyrosine is catalyzed into levodopa (or L-DOPA) by tyrosine hydroxylase, and levodopa is then converted into dopamine by the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase.

- Serotonergic neurons—serotonin. Serotonin (5-Hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) can act as excitatory or inhibitory. Of its four 5-HT receptor classes, 3 are GPCR and 1 is a ligand-gated cation channel. Serotonin is synthesized from tryptophan by tryptophan hydroxylase, and then further by decarboxylase. A lack of 5-HT at postsynaptic neurons has been linked to depression. Drugs that block the presynaptic serotonin transporter are used for treatment, such as Prozac and Zoloft.

- Purinergic neurons—ATP. ATP is a neurotransmitter acting at both ligand-gated ion channels (P2X receptors) and GPCRs (P2Y) receptors. ATP is, however, best known as a cotransmitter. Such purinergic signaling can also be mediated by other purines like adenosine, which particularly acts at P2Y receptors.

- Histaminergic neurons—histamine. Histamine is a monoamine neurotransmitter and neuromodulator. Histamine-producing neurons are found in the tuberomammillary nucleus of the hypothalamus.[27] Histamine is involved in arousal and regulating sleep/wake behaviors.

Multimodel classification

[edit]Since 2012 there has been a push from the cellular and computational neuroscience community to come up with a universal classification of neurons that will apply to all neurons in the brain as well as across species. This is done by considering the three essential qualities of all neurons: electrophysiology, morphology, and the individual transcriptome of the cells. Besides being universal this classification has the advantage of being able to classify astrocytes as well. A method called patch-sequencing in which all three qualities can be measured at once is used extensively by the Allen Institute for Brain Science.[28] In 2023, a comprehensive cell atlas of the adult, and developing human brain at the transcriptional, epigenetic, and functional levels was created through an international collaboration of researchers using the most cutting-edge molecular biology approaches.[29]

Connectivity

[edit]

Neurons communicate with each other via synapses, where either the axon terminal of one cell contacts another neuron's dendrite, soma, or, less commonly, axon. Neurons such as Purkinje cells in the cerebellum can have over 1000 dendritic branches, making connections with tens of thousands of other cells; other neurons, such as the magnocellular neurons of the supraoptic nucleus, have only one or two dendrites, each of which receives thousands of synapses.

Synapses can be excitatory or inhibitory, either increasing or decreasing activity in the target neuron, respectively. Some neurons also communicate via electrical synapses, which are direct, electrically conductive junctions between cells.[30]

When an action potential reaches the axon terminal, it opens voltage-gated calcium channels, allowing calcium ions to enter the terminal. Calcium causes synaptic vesicles filled with neurotransmitter molecules to fuse with the membrane, releasing their contents into the synaptic cleft. The neurotransmitters diffuse across the synaptic cleft and activate receptors on the postsynaptic neuron. High cytosolic calcium in the axon terminal triggers mitochondrial calcium uptake, which, in turn, activates mitochondrial energy metabolism to produce ATP to support continuous neurotransmission.[31]

An autapse is a synapse in which a neuron's axon connects to its dendrites.

The human brain has some 8.6 x 1010 (eighty six billion) neurons.[32][33] Each neuron has on average 7,000 synaptic connections to other neurons. It has been estimated that the brain of a three-year-old child has about 1015 synapses (1 quadrillion). This number declines with age, stabilizing by adulthood. Estimates vary for an adult, ranging from 1014 to 5 x 1014 synapses (100 to 500 trillion).[34]

Nonelectrochemical signaling

[edit]Beyond electrical and chemical signaling, studies suggest neurons in healthy human brains can also communicate through:

- force generated by the enlargement of dendritic spines[35]

- the transfer of proteins – transneuronally transported proteins (TNTPs)[36][37]

They can also get modulated by input from the environment and hormones released from other parts of the organism,[38] which could be influenced more or less directly by neurons. This also applies to neurotrophins such as BDNF. The gut microbiome is also connected with the brain.[39] Neurons also communicate with microglia, the brain's main immune cells via specialized contact sites, called "somatic junctions". These connections enable microglia to constantly monitor and regulate neuronal functions, and exert neuroprotection when needed.[40]

Mechanisms for propagating action potentials

[edit]In 1937 John Zachary Young suggested that the squid giant axon could be used to study neuronal electrical properties.[41] It is larger than but similar to human neurons, making it easier to study. By inserting electrodes into the squid giant axons, accurate measurements were made of the membrane potential.

The cell membrane of the axon and soma contain voltage-gated ion channels that allow the neuron to generate and propagate an electrical signal (an action potential). Some neurons also generate subthreshold membrane potential oscillations. These signals are generated and propagated by charge-carrying ions including sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), chloride (Cl−), and calcium (Ca2+).

Several stimuli can activate a neuron leading to electrical activity, including pressure, stretch, chemical transmitters, and changes in the electric potential across the cell membrane.[42] Stimuli cause specific ion-channels within the cell membrane to open, leading to a flow of ions through the cell membrane, changing the membrane potential. Neurons must maintain the specific electrical properties that define their neuron type.[43]

Thin neurons and axons require less metabolic expense to produce and carry action potentials, but thicker axons convey impulses more rapidly. To minimize metabolic expense while maintaining rapid conduction, many neurons have insulating sheaths of myelin around their axons. The sheaths are formed by glial cells: oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system. The sheath enables action potentials to travel faster than in unmyelinated axons of the same diameter, whilst using less energy. The myelin sheath in peripheral nerves normally runs along the axon in sections about 1 mm long, punctuated by unsheathed nodes of Ranvier, which contain a high density of voltage-gated ion channels. Multiple sclerosis is a neurological disorder that results from the demyelination of axons in the central nervous system.

Some neurons do not generate action potentials but instead generate a graded electrical signal, which in turn causes graded neurotransmitter release. Such non-spiking neurons tend to be sensory neurons or interneurons, because they cannot carry signals long distances.

Neural coding

[edit]Neural coding is concerned with how sensory and other information is represented in the brain by neurons. The main goal of studying neural coding is to characterize the relationship between the stimulus and the individual or ensemble neuronal responses and the relationships among the electrical activities of the neurons within the ensemble.[44] It is thought that neurons can encode both digital and analog information.[45]

All-or-none principle

[edit]

The conduction of nerve impulses is an example of an all-or-none response. In other words, if a neuron responds at all, then it must respond completely. Greater intensity of stimulation, like brighter image/louder sound, does not produce a stronger signal but can increase firing frequency.[46]: 31 Receptors respond in different ways to stimuli. Slowly adapting or tonic receptors respond to a steady stimulus and produce a steady rate of firing. Tonic receptors most often respond to increased stimulus intensity by increasing their firing frequency, usually as a power function of stimulus plotted against impulses per second. This can be likened to an intrinsic property of light where greater intensity of a specific frequency (color) requires more photons, as the photons can not become "stronger" for a specific frequency.

Other receptor types include quickly adapting or phasic receptors, where firing decreases or stops with a steady stimulus; examples include skin which, when touched causes neurons to fire, but if the object maintains even pressure, the neurons stop firing. The neurons of the skin and muscles that are responsive to pressure and vibration have filtering accessory structures that aid their function.

The pacinian corpuscle is one such structure. It has concentric layers like an onion, which form around the axon terminal. When pressure is applied and the corpuscle is deformed, mechanical stimulus is transferred to the axon, which fires. If the pressure is steady, the stimulus ends; thus, these neurons typically respond with a transient depolarization during the initial deformation and again when the pressure is removed, which causes the corpuscle to change shape again. Other types of adaptation are important in extending the function of several other neurons.[47]

Although neurons have long been assumed to always give a stereotyped maximal response or none at all, there is a body of research that argues that this is only partially correct, and that while it is true that Neurons either fire an Action Potential or do not, the amplitude and duration of the Action Potentials that a Neuron fires can vary greatly, allowing the Neuron to encode information in at least the strength of the Action Potential. Additionally, the analog information carried in the Action Potential has been shown to be able to survive and travel distances originally not thought to be possible. This has been proposed to be a highly effective way to encode information compared to the usual rate and temporal coding theories commonly seen in the literature, with the ability to transfer around 4 times more information than current wisdom would suggest.[48][49][50][51][52]

Etymology and spelling

[edit]The German anatomist Heinrich Wilhelm Waldeyer introduced the term neuron in 1891,[53] based on the ancient Greek νεῦρον neuron 'sinew, cord, nerve'.[54]

The word was adopted in French with the spelling neurone. That spelling was also used by many writers in English,[55] but has now become rare in American usage and uncommon in British usage.[56][54]

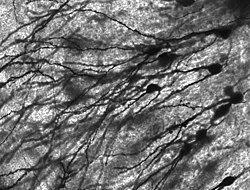

Some previous works used nerve cell (cellule nervose), as adopted in Camillo Golgi's 1873 paper on the discovery of the silver staining technique used to visualize nervous tissue under light microscopy.[57]

History

[edit]

The neuron's place as the primary functional unit of the nervous system was first recognized in the late 19th century through the work of the Spanish anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal.[58]

To make the structure of individual neurons visible, Ramón y Cajal improved a silver staining process that had been developed by Camillo Golgi.[58] The improved process involves a technique called "double impregnation" and is still in use.

In 1888 Ramón y Cajal published a paper about the bird cerebellum. In this paper, he stated that he could not find evidence for anastomosis between axons and dendrites and called each nervous element "an autonomous canton."[58][53] This became known as the neuron doctrine, one of the central tenets of modern neuroscience.[58]

In 1891, the German anatomist Heinrich Wilhelm Waldeyer wrote a highly influential review of the neuron doctrine in which he introduced the term neuron to describe the anatomical and physiological unit of the nervous system.[59][60]

The silver impregnation stains are a useful method for neuroanatomical investigations because, for reasons unknown, it stains only a small percentage of cells in a tissue, exposing the complete micro structure of individual neurons without much overlap from other cells.[61]

Neuron doctrine

[edit]

The neuron doctrine is the now fundamental idea that neurons are the basic structural and functional units of the nervous system. The theory was put forward by Santiago Ramón y Cajal in the late 19th century. It held that neurons are discrete cells (not connected in a meshwork), acting as metabolically distinct units.

Later discoveries yielded refinements to the doctrine. For example, glial cells, which are non-neuronal, play an essential role in information processing.[62] Also, electrical synapses are more common than previously thought,[63] comprising direct, cytoplasmic connections between neurons; In fact, neurons can form even tighter couplings: the squid giant axon arises from the fusion of multiple axons.[64]

Ramón y Cajal also postulated the Law of Dynamic Polarization, which states that a neuron receives signals at its dendrites and cell body and transmits them, as action potentials, along the axon in one direction: away from the cell body.[65] The Law of Dynamic Polarization has important exceptions; dendrites can serve as synaptic output sites of neurons[66] and axons can receive synaptic inputs.[67]

Compartmental modelling of neurons

[edit]Although neurons are often described as "fundamental units" of the brain, they perform internal computations. Neurons integrate input within dendrites, and this complexity is lost in models that assume neurons to be a fundamental unit. Dendritic branches can be modeled as spatial compartments, whose activity is related to passive membrane properties, but may also be different depending on input from synapses. Compartmental modelling of dendrites is especially helpful for understanding the behavior of neurons that are too small to record with electrodes, as is the case for Drosophila melanogaster.[68]

Neurons in the brain

[edit]The number of neurons in the brain varies dramatically from species to species.[69] In a human, there are an estimated 10–20 billion neurons in the cerebral cortex and 55–70 billion neurons in the cerebellum.[70] By contrast, the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans has just 302 neurons, making it an ideal model organism as scientists have been able to map all of its neurons. The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, a common subject in biological experiments, has around 100,000 neurons and exhibits many complex behaviors. Many properties of neurons, from the type of neurotransmitters used to ion channel composition, are maintained across species, allowing scientists to study processes occurring in more complex organisms in much simpler experimental systems.

Neurological disorders

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) is a heterogeneous inherited disorder of nerves (neuropathy) that is characterized by loss of muscle tissue and touch sensation, predominantly in the feet and legs extending to the hands and arms in advanced stages. Presently incurable, this disease is one of the most common inherited neurological disorders, affecting 36 in 100,000 people.[71]

Alzheimer's disease (AD), also known simply as Alzheimer's, is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive cognitive deterioration, together with declining activities of daily living and neuropsychiatric symptoms or behavioral changes.[72] The most striking early symptom is loss of short-term memory (amnesia), which usually manifests as minor forgetfulness that becomes steadily more pronounced with illness progression, with relative preservation of older memories. As the disorder progresses, cognitive (intellectual) impairment extends to the domains of language (aphasia), skilled movements (apraxia), and recognition (agnosia), and functions such as decision-making and planning become impaired.[73][74]

Parkinson's disease (PD), also known as Parkinson's, is a degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that often impairs motor skills and speech.[75] Parkinson's disease belongs to a group of conditions called movement disorders.[76] It is characterized by muscle rigidity, tremor, a slowing of physical movement (bradykinesia), and in extreme cases, a loss of physical movement (akinesia). The primary symptoms are the results of decreased stimulation of the motor cortex by the basal ganglia, normally caused by the insufficient formation and action of dopamine, which is produced in the dopaminergic neurons of the brain. Secondary symptoms may include high-level cognitive dysfunction and subtle language problems. PD is both chronic and progressive.

Myasthenia gravis is a neuromuscular disease leading to fluctuating muscle weakness and fatigability during simple activities. Weakness is typically caused by circulating antibodies that block acetylcholine receptors at the postsynaptic neuromuscular junction, inhibiting the stimulative effect of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Myasthenia is treated with immunosuppressants, cholinesterase inhibitors and, in selected cases, thymectomy.

Demyelination

[edit]

Demyelination is a process characterized by the gradual loss of the myelin sheath enveloping nerve fibers. When myelin deteriorates, signal conduction along nerves can be significantly impaired or lost, and the nerve eventually withers. Demyelination may affect both central and peripheral nervous systems, contributing to various neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Although demyelination is often caused by an autoimmune reaction, it may also be caused by viral infections, metabolic disorders, trauma, and some medications.

Axonal degeneration

[edit]Although most injury responses include a calcium influx signaling to promote resealing of severed parts, axonal injuries initially lead to acute axonal degeneration, which is the rapid separation of the proximal and distal ends, occurring within 30 minutes of injury.[77] Degeneration follows with swelling of the axolemma, and eventually leads to bead-like formation. Granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton and inner organelles occurs after axolemma degradation. Early changes include accumulation of mitochondria in the paranodal regions at the site of injury. The endoplasmic reticulum degrades and mitochondria swell up and eventually disintegrate. The disintegration is dependent on ubiquitin and calpain proteases (caused by the influx of calcium ions), suggesting that axonal degeneration is an active process that produces complete fragmentation. The process takes about roughly 24 hours in the PNS and longer in the CNS. The signaling pathways leading to axolemma degeneration are unknown.

Development

[edit]Neurons develop through the process of neurogenesis, in which neural stem cells divide to produce differentiated neurons. Once fully differentiated they are no longer capable of undergoing mitosis. Neurogenesis primarily occurs during embryonic development.

Neurons initially develop from the neural tube in the embryo. The neural tube has three layers – a ventricular zone, an intermediate zone, and a marginal zone. The ventricular zone surrounds the tube's central canal and becomes the ependyma. Dividing cells of the ventricular zone form the intermediate zone which stretches to the outermost layer of the neural tube called the pial layer. The gray matter of the brain is derived from the intermediate zone. The extensions of the neurons in the intermediate zone make up the marginal zone when myelinated becomes the brain's white matter.[78]

Differentiation of the neurons is ordered by their size. Large motor neurons are first. Smaller sensory neurons together with glial cell differentiate at birth.[78]

Adult neurogenesis can occur and studies of the age of human neurons suggest that this process occurs only for a minority of cells and that the vast majority of neurons in the neocortex form before birth and persist without replacement. The extent to which adult neurogenesis exists in humans, and its contribution to cognition are controversial, with conflicting reports published in 2018.[79]

The body contains a variety of stem cell types that can differentiate into neurons. Researchers found a way to transform human skin cells into nerve cells using transdifferentiation, in which "cells are forced to adopt new identities".[80]

During neurogenesis in the mammalian brain, progenitor and stem cells progress from proliferative divisions to differentiative divisions. This progression leads to the neurons and glia that populate cortical layers. Epigenetic modifications play a key role in regulating gene expression in differentiating neural stem cells, and are critical for cell fate determination in the developing and adult mammalian brain. Epigenetic modifications include DNA cytosine methylation to form 5-methylcytosine and 5-methylcytosine demethylation.[81] DNA cytosine methylation is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). Methylcytosine demethylation is catalyzed in several stages by TET enzymes that carry out oxidative reactions (e.g. 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine) and enzymes of the DNA base excision repair (BER) pathway.[81]

At different stages of mammalian nervous system development, two DNA repair processes are employed in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. These pathways are homologous recombinational repair used in proliferating neural precursor cells, and non-homologous end joining used mainly at later developmental stages[82]

Intercellular communication between developing neurons and microglia is also indispensable for proper neurogenesis and brain development.[83]

Nerve regeneration

[edit]Peripheral axons can regrow if they are severed,[84] but one neuron cannot be functionally replaced by one of another type (Llinás' law).[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/neurone

- ^ Najle, Sebastián R.; Grau-Bové, Xavier; Elek, Anamaria; Navarrete, Cristina; Cianferoni, Damiano; Chiva, Cristina; Cañas-Armenteros, Didac; Mallabiabarrena, Arrate; Kamm, Kai; Sabidó, Eduard; Gruber-Vodicka, Harald; Schierwater, Bernd; Serrano, Luis; Sebé-Pedrós, Arnau (Oct 2023). "Stepwise emergence of the neuronal gene expression program in early animal evolution". Cell. 186 (21): 4676–4693.e29. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.027. PMC 10580291. PMID 37729907.

- ^ Zayia LC, Tadi P. Neuroanatomy, Motor Neuron. [Updated 2022 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (June 8, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 12.2 Nervous tissue. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (June 8, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 12.2 Nervous tissue. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

- ^ Moore, Keith; Dalley, Arthur (2005). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (5th ed.). LWW. pp. 47. ISBN 0-7817-3639-0.

A bundle of nerve fibers (axons) connecting neighboring or distant nuclei of the CNS is a tract.

- ^ "What are the parts of the nervous system?". October 2018. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ^ Davies, Melissa (2002-04-09). "The Neuron: size comparison". Neuroscience: A journey through the brain. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Chudler EH. "Brain Facts and Figures". Neuroscience for Kids. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ J.H. Smith, C. Rowland, B. Harland, S. Moslehi, K. Schobert, R.M. Montgomery, W.J. Watterson, J. Dalrymple-Alford, R.P. Taylor, "How Neurons Exploit Fractal Geometry to Maximize Physical Connectivity", Scientific Reports, 11, 2332 (2021)

- ^ "16.7: Nervous System". Biology LibreTexts. 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ Herrup K, Yang Y (May 2007). "Cell cycle regulation in the postmitotic neuron: oxymoron or new biology?". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (5): 368–78. doi:10.1038/nrn2124. PMID 17453017. S2CID 12908713.

- ^ Talifu Z, Liu JY, Pan YZ, Ke H, Zhang CJ, Xu X, Gao F, Yu Y, Du LJ, Li JJ (April 2023). "In vivo astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming for central nervous system regeneration: a narrative review". Neural Regen Res. 18 (4): 750–755. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.353482. PMC 9700087. PMID 36204831.

- ^ Giménez, C. (February 1998). "[Composition and structure of the neuronal membrane: molecular basis of its physiology and pathology]". Revista de Neurologia. 26 (150): 232–239. ISSN 0210-0010. PMID 9563093.

- ^ State Hospitals Bulletin. State Commission in Lunacy. 1897. p. 378.

- ^ "Medical Definition of Neurotubules". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ Zecca L, Gallorini M, Schünemann V, Trautwein AX, Gerlach M, Riederer P, Vezzoni P, Tampellini D (March 2001). "Iron, neuromelanin and ferritin content in the substantia nigra of normal subjects at different ages: consequences for iron storage and neurodegenerative processes". Journal of Neurochemistry. 76 (6): 1766–73. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00186.x. PMID 11259494. S2CID 31301135.

- ^ Herrero MT, Hirsch EC, Kastner A, Luquin MR, Javoy-Agid F, Gonzalo LM, Obeso JA, Agid Y (1993). "Neuromelanin accumulation with age in catecholaminergic neurons from Macaca fascicularis brainstem". Developmental Neuroscience. 15 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1159/000111315. PMID 7505739.

- ^ Brunk UT, Terman A (September 2002). "Lipofuscin: mechanisms of age-related accumulation and influence on cell function". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 33 (5): 611–9. doi:10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00959-0. PMID 12208347.

- ^ Zhao B, Meka DP, Schellenberg R, König T, Schwanke B, Kobler O, Windhorst S, Kreutz MR, Mikhaylova M, Calderon de Anda F (August 2017). "Microtubules Modulate F-actin Dynamics during Neuronal Polarization". Scientific Reports. 7 (1) 9583. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.9583Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09832-8. PMC 5575062. PMID 28851982.

- ^ Lee WC, Huang H, Feng G, Sanes JR, Brown EN, So PT, Nedivi E (February 2006). "Dynamic remodeling of dendritic arbors in GABAergic interneurons of adult visual cortex". PLOS Biology. 4 (2) e29. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040029. PMC 1318477. PMID 16366735.

- ^ Al, Martini, Frederic Et (2005). Anatomy and Physiology' 2007 Ed.2007 Edition. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 288. ISBN 978-971-23-4807-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gerber U (January 2003). "Metabotropic glutamate receptors in vertebrate retina". Documenta Ophthalmologica. Advances in Ophthalmology. 106 (1): 83–7. doi:10.1023/A:1022477203420. PMID 12675489. S2CID 22296630.

- ^ Wilson NR, Runyan CA, Wang FL, Sur M (August 2012). "Division and subtraction by distinct cortical inhibitory networks in vivo". Nature. 488 (7411): 343–8. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..343W. doi:10.1038/nature11347. hdl:1721.1/92709. PMC 3653570. PMID 22878717.

- ^ a b Llinás RR (2014-01-01). "Intrinsic electrical properties of mammalian neurons and CNS function: a historical perspective". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 8: 320. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00320. PMC 4219458. PMID 25408634.

- ^ Kolodin YO, Veselovskaia NN, Veselovsky NS, Fedulova SA. Ion conductances related to shaping the repetitive firing in rat retinal ganglion cells. Acta Physiologica Congress. Archived from the original on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ "Ionic conductances underlying excitability in tonically firing retinal ganglion cells of adult rat". Ykolodin.50webs.com. 2008-04-27. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ^ Scammell TE, Jackson AC, Franks NP, Wisden W, Dauvilliers Y (January 2019). "Histamine: neural circuits and new medications". Sleep. 42 (1). doi:10.1093/sleep/zsy183. PMC 6335869. PMID 30239935.

- ^ "Patch-seq technique helps depict the variation of neural cells in the brain". News-medical.net. 3 December 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Science AAAS. "BRAIN CELL CENSUS". Retrieved 2023-10-17.

- ^ Macpherson, Gordon (2002). Black's Medical Dictionary (40 ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. pp. 431–434. ISBN 0-8108-4984-4.

- ^ Ivannikov MV, Macleod GT (June 2013). "Mitochondrial free Ca²⁺ levels and their effects on energy metabolism in Drosophila motor nerve terminals". Biophysical Journal. 104 (11): 2353–61. Bibcode:2013BpJ...104.2353I. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.064. PMC 3672877. PMID 23746507.

- ^ Herculano-Houzel S (November 2009). "The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 3: 31. doi:10.3389/neuro.09.031.2009. PMC 2776484. PMID 19915731.

- ^ "Why is the human brain so difficult to understand? We asked 4 neuroscientists". Allen Institute. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Drachman DA (June 2005). "Do we have brain to spare?". Neurology. 64 (12): 2004–5. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000166914.38327.BB. PMID 15985565. S2CID 38482114.

- ^ Ucar, Hasan; Watanabe, Satoshi; Noguchi, Jun; Morimoto, Yuichi; Iino, Yusuke; Yagishita, Sho; Takahashi, Noriko; Kasai, Haruo (December 2021). "Mechanical actions of dendritic-spine enlargement on presynaptic exocytosis". Nature. 600 (7890): 686–689. Bibcode:2021Natur.600..686U. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04125-7. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34819666. S2CID 244648506.

Lay summary:

"Forceful synapses reveal mechanical interactions in the brain". Nature. 24 November 2021. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-03516-0. Retrieved 21 February 2022. - ^ "Researchers discover new type of cellular communication in the brain". The Scripps Research Institute. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Schiapparelli, Lucio M.; Sharma, Pranav; He, Hai-Yan; Li, Jianli; Shah, Sahil H.; McClatchy, Daniel B.; Ma, Yuanhui; Liu, Han-Hsuan; Goldberg, Jeffrey L.; Yates, John R.; Cline, Hollis T. (25 January 2022). "Proteomic screen reveals diverse protein transport between connected neurons in the visual system". Cell Reports. 38 (4) 110287. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110287. ISSN 2211-1247. PMC 8906846. PMID 35081342.

- ^ Levitan, Irwin B.; Kaczmarek, Leonard K. (2015). "Electrical Signaling in Neurons". The Neuron. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–62. doi:10.1093/med/9780199773893.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-977389-3.

- ^ O'Leary, Olivia F.; Ogbonnaya, Ebere S.; Felice, Daniela; Levone, Brunno R.; C. Conroy, Lorraine; Fitzgerald, Patrick; Bravo, Javier A.; Forsythe, Paul; Bienenstock, John; Dinan, Timothy G.; Cryan, John F. (1 February 2018). "The vagus nerve modulates BDNF expression and neurogenesis in the hippocampus". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (2): 307–316. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.12.004. ISSN 0924-977X. PMID 29426666. S2CID 46819013.

- ^ Cserép C, Pósfai B, Lénárt N, Fekete R, László ZI, Lele Z (January 2020). "Microglia monitor and protect neuronal function through specialized somatic purinergic junctions". Science. 367 (6477): 528–537. Bibcode:2020Sci...367..528C. doi:10.1126/science.aax6752. PMID 31831638. S2CID 209343260.

- ^ Chudler EH. "Milestones in Neuroscience Research". Neuroscience for Kids. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Patlak J, Gibbons R (2000-11-01). "Electrical Activity of Nerves". Action Potentials in Nerve Cells. Archived from the original on August 27, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Harris-Warrick, RM (October 2011). "Neuromodulation and flexibility in Central Pattern Generator networks". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 21 (5): 685–92. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2011.05.011. PMC 3171584. PMID 21646013.

- ^ Brown EN, Kass RE, Mitra PP (May 2004). "Multiple neural spike train data analysis: state-of-the-art and future challenges". Nature Neuroscience. 7 (5): 456–61. doi:10.1038/nn1228. PMID 15114358. S2CID 562815.

- ^ Thorpe SJ (1990). "Spike arrival times: A highly efficient coding scheme for neural networks" (PDF). In Eckmiller R, Hartmann G, Hauske G (eds.). Parallel processing in neural systems and computers. North-Holland. pp. 91–94. ISBN 978-0-444-88390-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-15.

- ^ a b Kalat, James W (2016). Biological psychology (12 ed.). Australia: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-305-10540-9. OCLC 898154491.

- ^ Eckert R, Randall D (1983). Animal physiology: mechanisms and adaptations. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-7167-1423-1.

- ^ Juusola, Mikko; Robinson, Hugh P. C.; de Polavieja, Gonzalo G. (February 2007). "Coding with spike shapes and graded potentials in cortical networks". BioEssays: News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology. pp. 178–187. doi:10.1002/bies.20532.

- ^ "Myelination Increases the Spatial Extent of Analog Modulation of Synaptic Transmission: A Modeling Study". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience.

- ^ Zbili, M.; Debanne, D. (2019). "Past and Future of Analog-Digital Modulation of Synaptic Transmission". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 13: 160. doi:10.3389/fncel.2019.00160. PMC 6492051. PMID 31105529.

- ^ Clark, Beverley; Häusser, Michael (8 August 2006). "Neural Coding: Analog Signalling in Axons". Current Biology. 16 (15): R585 – R588. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.007. PMID 16890514. S2CID 8295969.

- ^ Liu, Wenke; Liu, Qing; Crozier, Robert A.; Davis, Robin L. (2021). "Analog transmission of action potential fine structure in spiral ganglion axons". Journal of Neurophysiology. 126 (3): 888–905. doi:10.1152/jn.00237.2021. PMC 8461829. PMID 34346782.

- ^ a b Finger, Stanley (1994). Origins of neuroscience: a history of explorations into brain function. Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3. OCLC 27151391.

Ramon y Cajal's first paper on the Golgi stain was on the bird cerebellum, and it appeared in the Revista in 1888. He acknowledged that he found the nerve fibers to be very intricate, but stated that he could find no evidence for either axons or dendrites undergoing anastomosis and forming nets. He called each nervous element 'an autonomous canton.'

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, 2003, s.v.

- ^ Mehta AR, Mehta PR, Anderson SP, MacKinnon BL, Compston A (January 2020). "Grey Matter Etymology and the neuron(e)". Brain. 143 (1): 374–379. doi:10.1093/brain/awz367. PMC 6935745. PMID 31844876.

- ^ "Google Books Ngram Viewer". books.google.com. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Golgi, C. (1873). Sulla struttura della sostanza grigia del cervello (Comunicazione preventiva). Gaz. Med. Ital. Lomb. 33, 244–246. [1].

- ^ a b c d López-Muñoz F, Boya J, Alamo C (October 2006). "Neuron theory, the cornerstone of neuroscience, on the centenary of the Nobel Prize award to Santiago Ramón y Cajal". Brain Research Bulletin. 70 (4–6): 391–405. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.07.010. PMID 17027775. S2CID 11273256.

- ^ Finger, Stanley (1994). Origins of neuroscience: a history of explorations into brain function. Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3. OCLC 27151391.

... a man who would write a highly influential review of the evidence in favor of the neuron doctrine two years later. In his paper, Waldeyer (1891), ... , wrote that nerve cells terminate freely with end arborizations and that the 'neuron' is the anatomical and physiological unit of the nervous system. The word 'neuron' was born this way.

- ^ "Whonamedit - dictionary of medical eponyms". www.whonamedit.com.

Today, Wilhelm von Waldeyer-Hartz is remembered as the founder of the neurone theory, coining the term "neurone" to describe the cellular function unit of the nervous system and enunciating and clarifying that concept in 1891.

- ^ Grant G (October 2007). "How the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was shared between Golgi and Cajal". Brain Research Reviews. 55 (2): 490–8. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.004. PMID 17306375. S2CID 24331507.

- ^ Witcher MR, Kirov SA, Harris KM (January 2007). "Plasticity of perisynaptic astroglia during synaptogenesis in the mature rat hippocampus". Glia. 55 (1): 13–23. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.598.7002. doi:10.1002/glia.20415. PMID 17001633. S2CID 10664003.

- ^ Connors BW, Long MA (2004). "Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 27 (1): 393–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131128. PMID 15217338.

- ^ Guillery RW (June 2005). "Observations of synaptic structures: origins of the neuron doctrine and its current status". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 360 (1458): 1281–307. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1459. PMC 1569502. PMID 16147523.

- ^ Sabbatini RM (April–July 2003). "Neurons and Synapses: The History of Its Discovery". Brain & Mind Magazine: 17.

- ^ Djurisic M, Antic S, Chen WR, Zecevic D (July 2004). "Voltage imaging from dendrites of mitral cells: EPSP attenuation and spike trigger zones". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (30): 6703–14. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0307-04.2004. hdl:1912/2958. PMC 6729725. PMID 15282273.

- ^ Cochilla AJ, Alford S (March 1997). "Glutamate receptor-mediated synaptic excitation in axons of the lamprey". The Journal of Physiology. 499 (Pt 2): 443–57. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021940. PMC 1159318. PMID 9080373.

- ^ Gouwens NW, Wilson RI (2009). "Signal propagation in Drosophila central neurons". Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (19): 6239–6249. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0764-09.2009. PMC 2709801. PMID 19439602.

- ^ Williams RW, Herrup K (1988). "The control of neuron number". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 11 (1): 423–53. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.002231. PMID 3284447.

- ^ von Bartheld CS, Bahney J, Herculano-Houzel S (December 2016). "The search for true numbers of neurons and glial cells in the human brain: A review of 150 years of cell counting". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 524 (18): 3865–3895. doi:10.1002/cne.24040. PMC 5063692. PMID 27187682.

- ^ Krajewski KM, Lewis RA, Fuerst DR, Turansky C, Hinderer SR, Garbern J, Kamholz J, Shy ME (July 2000). "Neurological dysfunction and axonal degeneration in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A". Brain. 123 (7): 1516–27. doi:10.1093/brain/123.7.1516. PMID 10869062.

- ^ "About Alzheimer's Disease: Symptoms". National Institute on Aging. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Burns A, Iliffe S (February 2009). "Alzheimer's disease". BMJ. 338: b158. doi:10.1136/bmj.b158. PMID 19196745. S2CID 8570146.

- ^ Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM (January 2010). "Alzheimer's disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (4): 329–44. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0909142. PMID 20107219. S2CID 205115756.

- ^ "Parkinson's Disease Information Page". NINDS. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ "Movement Disorders". The International Neuromodulation Society.

- ^ Kerschensteiner M, Schwab ME, Lichtman JW, Misgeld T (May 2005). "In vivo imaging of axonal degeneration and regeneration in the injured spinal cord". Nature Medicine. 11 (5): 572–7. doi:10.1038/nm1229. PMID 15821747. S2CID 25287010.

- ^ a b Caire, Michael J.; Reddy, Vamsi; Varacallo, Matthew (2024). "Physiology, Synapse". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30252303. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Kempermann G, Gage FH, Aigner L, Song H, Curtis MA, Thuret S, Kuhn HG, Jessberger S, Frankland PW, Cameron HA, Gould E, Hen R, Abrous DN, Toni N, Schinder AF, Zhao X, Lucassen PJ, Frisén J (July 2018). "Human Adult Neurogenesis: Evidence and Remaining Questions". Cell Stem Cell. 23 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2018.04.004. PMC 6035081. PMID 29681514.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (26 May 2011). "How to make a human neuron". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.328.

By transforming cells from human skin into working nerve cells, researchers may have come up with a model for nervous-system diseases and perhaps even regenerative therapies based on cell transplants. The achievement, reported online today in Nature, is the latest in a fast-moving field called transdifferentiation, in which cells are forced to adopt new identities. In the past year, researchers have converted connective tissue cells found in the skin into heart cells, blood cells, and liver cells.

- ^ a b Wang Z, Tang B, He Y, Jin P (March 2016). "DNA methylation dynamics in neurogenesis". Epigenomics. 8 (3): 401–14. doi:10.2217/epi.15.119. PMC 4864063. PMID 26950681.

- ^ Orii KE, Lee Y, Kondo N, McKinnon PJ (June 2006). "Selective utilization of nonhomologous end-joining and homologous recombination DNA repair pathways during nervous system development". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (26): 10017–22. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10310017O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602436103. PMC 1502498. PMID 16777961.

- ^ Cserép, Csaba; Schwarcz, Anett D.; Pósfai, Balázs; László, Zsófia I.; Kellermayer, Anna; Környei, Zsuzsanna; Kisfali, Máté; Nyerges, Miklós; Lele, Zsolt; Katona, István (September 2022). "Microglial control of neuronal development via somatic purinergic junctions". Cell Reports. 40 (12) 111369. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111369. PMC 9513806. PMID 36130488. S2CID 252416407.

- ^ Yiu G, He Z (August 2006). "Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 7 (8): 617–27. doi:10.1038/nrn1956. PMC 2693386. PMID 16858390.

Further reading

[edit]- Bullock TH, Bennett MV, Johnston D, Josephson R, Marder E, Fields RD (November 2005). "Neuroscience. The neuron doctrine, redux". Science. 310 (5749): 791–3. doi:10.1126/science.1114394. PMID 16272104. S2CID 170670241.

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM (2000). Principles of Neural Science (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-8385-7701-6.

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HS (1991). The Fine Structure of the Nervous System (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506571-9.

- Ramón y Cajal S (1933). Histology (10th ed.). Baltimore: Wood.

- Roberts A, Bush BM (1981). Neurones without Impulses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29935-7.

- Snell RS (2010). Clinical Neuroanatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-9427-5.

External links

[edit]- IBRO (International Brain Research Organization). Fostering neuroscience research especially in less well-funded countries.

- NeuronBank Archived 2021-04-13 at the Wayback Machine an online neuromics tool for cataloging neuronal types and synaptic connectivity.

- High Resolution Neuroanatomical Images of Primate and Non-Primate Brains.

- The Department of Neuroscience at Wikiversity, which presently offers two courses: Fundamentals of Neuroscience and Comparative Neuroscience.

- NIF Search – Neuron Archived 2015-01-22 at the Wayback Machine via the Neuroscience Information Framework

- Cell Centered Database – Neuron

- Complete list of neuron types according to the Petilla convention, at NeuroLex.

- NeuroMorpho.Org an online database of digital reconstructions of neuronal morphology.

- Immunohistochemistry Image Gallery: Neuron

- Khan Academy: Anatomy of a neuron

- Neuron images