Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

p53, also known as tumor protein p53, TP53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53) is a regulatory transcription factor protein that is often mutated in human cancers. The p53 proteins (originally thought to be, and often spoken of as, a single protein) are crucial in vertebrates, where they prevent cancer formation.[5] As such, p53 has been described as "the guardian of the genome" because of its role in conserving stability by preventing genome mutation.[6] Hence TP53[note 1] is classified as a tumor suppressor gene.[7][8][9][10][11]

The TP53 gene is the most frequently mutated gene (>50%) in human cancer, indicating that the TP53 gene plays a crucial role in preventing cancer formation.[5] TP53 gene encodes proteins that bind to DNA and regulate gene expression to prevent mutations of the genome.[12] In addition to the full-length protein, the human TP53 gene encodes at least 12 protein isoforms.[13]

Gene

[edit]In humans, the TP53 gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 17 (17p13.1).[7][8][9][10] The gene spans 20 kb, with a non-coding exon 1 and a very long first intron of 10 kb, overlapping the Hp53int1 gene. The coding sequence contains five regions showing a high degree of conservation in vertebrates, predominantly in exons 2, 5, 6, 7 and 8, but the sequences found in invertebrates show only distant resemblance to mammalian TP53.[14] TP53 orthologs[15] have been identified in most mammals for which complete genome data are available. Elephants, with 20 genes for TP53, rarely get cancer.[16]

Structure

[edit]

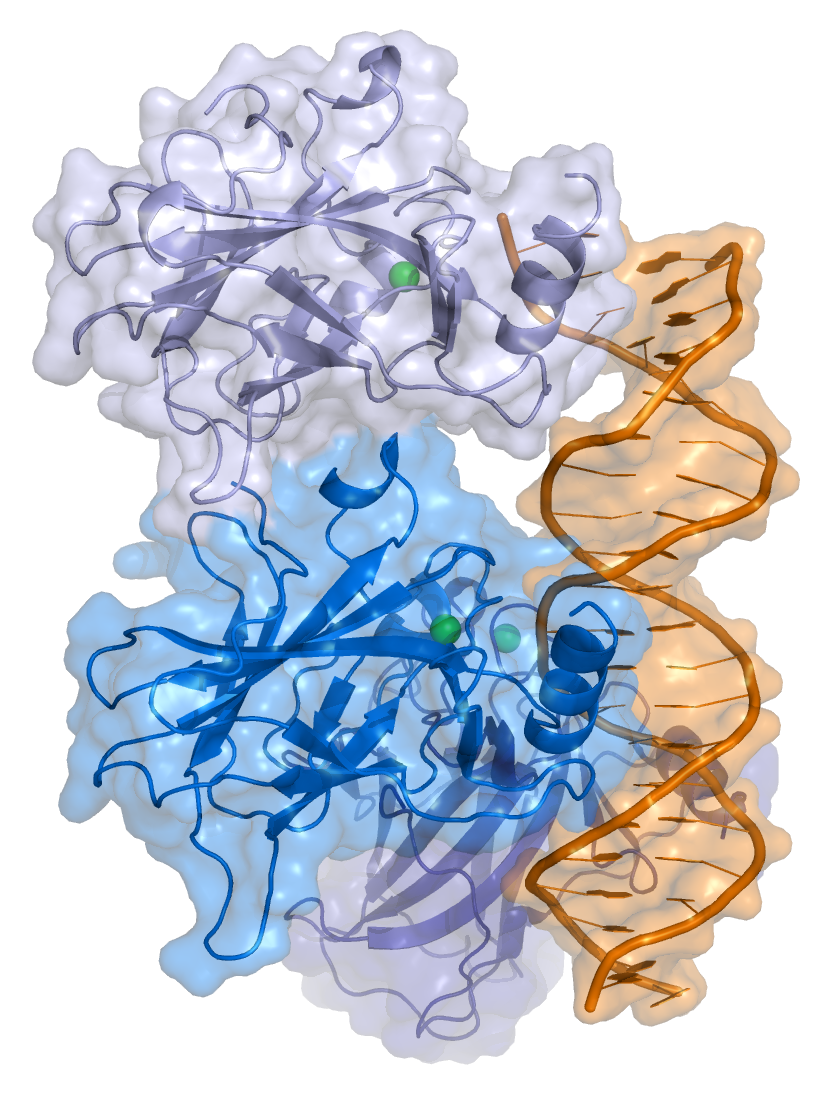

The full-length p53 protein (p53α) comprises seven distinct protein domains:

- An acidic N-terminus transactivation domain (TAD), including activation domains 1 and 2 (AD1: residues 1–42; AD2: residues 43–63), which regulate transcription of several pro-apoptotic genes.[17]

- A proline-rich domain (residues 64–92), involved in apoptotic function and nuclear export via MAPK signaling.

- A central DNA-binding domain (DBD; residues 102–292), containing a zinc atom and multiple arginine residues, essential for sequence-specific DNA interaction and co-repressor binding such as LMO3.[18]

- A nuclear localization sequence (NLS; residues 316–325), required for nuclear import.

- A homo-oligomerization domain (OD; residues 307–355), which mediates tetramerization—essential for p53 activity in vivo.

- A C-terminal regulatory domain (residues 356–393), which modulates the DNA-binding activity of the central domain.[19]

Most cancer-associated mutations in TP53 occur in the DBD, impairing DNA binding and transcriptional activation. These are typically recessive loss-of-function mutations. By contrast, mutations in the OD can exert dominant negative effects by forming inactive complexes with wild-type p53.

Wild-type p53 is a labile protein containing both folded and intrinsically disordered regions that act synergistically.[20]

Although designated as a 53 kDa protein by SDS-PAGE, the actual molecular weight of p53α is 43.7 kDa. The discrepancy is due to its high proline content, which slows electrophoretic migration.[21]

Tetramerization

[edit]p53 initially forms dimers cotranslationally during protein synthesis on ribosomes.[22] Each dimer consists of two p53 monomers joined through their oligomerization domains.[23]

The dimerization interface spans residues 325–356 and includes a beta-strand (residues 325–333), a alpha-helix (residues 335–356), and a sharp turn at the conserved hinge residue Gly334. This configuration links the beta-strand and alpha-helix to form a V-shaped monomer topology. The beta-strand contributes to the formation of an antiparallel intermolecular beta-sheet between two p53 monomers, stabilized by hydrophobic interactions involving Phe328, Leu330, and Ile332. The alpha-helix forms an antiparallel coiled-coil between the two monomers, with a packing angle of 156°. Helix–helix interactions are stabilized by hydrophobic contacts (e.g., Phe338, Phe341, Leu344) and electrostatic interactions, such as the Arg337–Asp352 salt bridge.

Following dimer formation, p53 dimers associate posttranslationally to form tetramers (dimers of dimers).[22][24] The tetramerization domain (residues 325–356) plays a central role in stabilizing the tetrameric structure.[24] In the tetramer, the two primary dimers associate at an angle described as "roughly orthogonal," with a helix bundle packing angle (θ) of approximately 80°.

Tetramers represent the active form of p53 for DNA binding and transcriptional regulation.[25][23]

Isoforms

[edit]Like 95% of human genes, TP53 encodes multiple proteins, collectively known as the p53 isoforms.[5] These vary in size from 3.5 to 43.7 kDa. Since their initial discovery in 2005, 12 human p53 isoforms have been identified: p53α, p53β, p53γ, ∆40p53α, ∆40p53β, ∆40p53γ, ∆133p53α, ∆133p53β, ∆133p53γ, ∆160p53α, ∆160p53β, and ∆160p53γ. Isoform expression is tissue-dependent, and p53α is never expressed alone.[11]

The isoforms differ by the inclusion or exclusion of specific domains. Some, such as Δ133p53β/γ and Δ160p53α/β/γ, lack the transactivation or proline-rich domains and are deficient in apoptosis induction, illustrating the functional diversity of TP53.[26][27]

Isoforms are generated through multiple mechanisms:

- Alternative splicing of intron 9 creates the β and γ isoforms with altered C-termini.

- An internal promoter in intron 4 produces the ∆133 and ∆160 isoforms, which lack part of the TAD and DBD.

- Alternative translation initiation at codons 40 or 160 results in ∆40p53 and ∆160p53 isoforms, respectively.[11]

Function

[edit]DNA damage and repair

[edit]

p53 regulates cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and genomic stability through multiple mechanisms:

- Activates DNA repair proteins in response to DNA damage,[28] suggesting a potential role in aging.[29]

- Arrests the cell cycle at the G1/S checkpoint upon DNA damage, allowing time for repair before progression.

- Initiates apoptosis if the damage is beyond repair.

- Essential for the senescence response triggered by short telomeres.

p53 functions as a transcription factor by binding DNA as a tetramer, a structure that is essential for its stability and effective DNA binding activity.[30] Once bound to DNA, p53 induces the transcription of numerous genes involved in DNA repair pathways. This includes components of base excision repair (BER) such as OGG1 and MUTYH, nucleotide excision repair (NER) factors like DDB2 and XPC, mismatch repair (MMR) genes such as MSH2 and MLH1, and elements of homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) repair.[31][32] These transcriptional responses are crucial for the DNA damage response (DDR), allowing cells to efficiently repair damaged DNA and maintain genomic integrity. While p53's role is most clearly defined in transcriptional activation of repair genes, it also participates in non-transcriptional regulation of DNA repair processes, particularly in HR and NHEJ, by modulating protein interactions and chromatin accessibility.[31][33]

p53 binds specific elements in the promoter of target genes, including CDKN1A, which encodes p21.[30][34] Upon activation by p53, p21 inhibits cyclin-dependent kinases, leading to cell cycle arrest and contributing to tumor suppression.[30][35] However, p21 can also be induced independently of p53 during processes such as differentiation, development, and in response to serum stimulation.[34]

p21 (WAF1) binds to cyclin-CDK complexes (notably CDK2, CDK1, CDK4, and CDK6), inhibiting their activity and blocking the G1/S transition.[36][37] This inhibition enforces a cell cycle pause that allows DNA repair to occur. In cells with functional p53, p21 is upregulated in response to DNA damage, ensuring this checkpoint control. In contrast, p53 mutations impair p21 induction and compromise this control.[30]

In human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), although p21 mRNA is upregulated following DNA damage, the protein is not detectable. This reflects a nonfunctional p53-p21 axis at the G1/S checkpoint.[38] This discrepancy is largely due to post-transcriptional repression, particularly by the miR-302 family of microRNAs, which inhibit p21 translation.[39] Although p53 binds the CDKN1A promoter in hESCs, it does not regulate miR-302, which is constitutively expressed and suppresses p21 expression.[39][38]

The p53 pathway is interconnected with the RB1 pathway via p14^ARF, which links the regulation of these key tumor suppressors.[40]

p53 expression can be induced by UV radiation, which also causes DNA damage. In this context, p53 activation can initiate processes that lead to melanin production and tanning.[41][42]

Stem cells

[edit]Levels of p53 play an important role in the maintenance of stem cells throughout development and the rest of human life.[43]

In human embryonic stem cells (hESCs)s, p53 is maintained at low inactive levels.[44] This is because activation of p53 leads to rapid differentiation of hESCs.[45] Studies have shown that knocking out p53 delays differentiation and that adding p53 causes spontaneous differentiation, showing how p53 promotes differentiation of hESCs and plays a key role in cell cycle as a differentiation regulator. When p53 becomes stabilized and activated in hESCs, it increases p21 to establish a longer G1. This typically leads to abolition of S-phase entry, which stops the cell cycle in G1, leading to differentiation. Work in mouse embryonic stem cells has recently shown however that the expression of P53 does not necessarily lead to differentiation.[46] p53 also activates miR-34a and miR-145, which then repress the hESCs pluripotency factors, further instigating differentiation.[44]

In adult stem cells, p53 regulation is important for maintenance of stemness in adult stem cell niches. Mechanical signals such as hypoxia affect levels of p53 in these niche cells through the hypoxia inducible factors, HIF-1α and HIF-2α. While HIF-1α stabilizes p53, HIF-2α suppresses it.[47] Suppression of p53 plays important roles in cancer stem cell phenotype, induced pluripotent stem cells and other stem cell roles and behaviors, such as blastema formation. Cells with decreased levels of p53 have been shown to reprogram into stem cells with a much greater efficiency than normal cells.[48][49] Papers suggest that the lack of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis gives more cells the chance to be reprogrammed. Decreased levels of p53 were also shown to be a crucial aspect of blastema formation in the legs of salamanders.[50] p53 regulation is very important in acting as a barrier between stem cells and a differentiated stem cell state, as well as a barrier between stem cells being functional and being cancerous.[51]

Other

[edit]

Apart from the cellular and molecular effects above, p53 has a tissue-level anticancer effect that works by inhibiting angiogenesis.[52] As tumors grow they need to recruit new blood vessels to supply them, and p53 inhibits that by (i) interfering with regulators of tumor hypoxia that also affect angiogenesis, such as HIF1 and HIF2, (ii) inhibiting the production of angiogenic promoting factors, and (iii) directly increasing the production of angiogenesis inhibitors, such as arresten.[53][54]

p53 by regulating Leukemia Inhibitory Factor has been shown to facilitate implantation in the mouse and possibly human reproduction.[55]

The immune response to infection also involves p53 and NF-κB. Checkpoint control of the cell cycle and of apoptosis by p53 is inhibited by some infections such as Mycoplasma bacteria,[56] raising the specter of oncogenic infection.

Regulation

[edit]

Basal regulation

[edit]Under normal, unstressed conditions, p53 is maintained at low levels through continuous degradation mediated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2 (HDM2 in humans).[57] MDM2 binds p53, exports it from the nucleus, and targets it for proteasomal degradation. Notably, p53 transcriptionally activates MDM2, establishing a classic negative feedback loop.

This feedback loop gives rise to damped oscillations in p53 levels, as demonstrated both experimentally[58] and in mathematical models.[59][60] These oscillations may determine cell fate decisions between survival and apoptosis.[61]

Activation by cellular stress

[edit]p53 is activated in response to a range of cellular stressors, including DNA damage (from ultraviolet or ionizing radiation, or oxidative chemicals),[62] osmotic shock, ribonucleotide depletion, oncogene activation, and viral pneumonia.[63]

Activation involves two main steps: stabilization of the protein, leading to its accumulation in the nucleus, and a conformational change that allows DNA binding and transcriptional activation. This process is initiated by phosphorylation of the N-terminal transactivation domain by stress-responsive kinases.[citation needed]

Stress-responsive kinases

[edit]Kinases that regulate p53 phosphorylation fall into two major categories. One group includes MAPK pathway members such as JNK1–3, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK, which respond to oxidative stress, membrane damage, and heat shock. The second group comprises DNA damage response kinases, including ATM, ATR, CHK1, CHK2, DNA-PK, CAK, and TP53RK, which respond to genomic instability. Oncogene-induced activation of p53 occurs via p14ARF, which inhibits MDM2 and thereby stabilizes p53.[citation needed]

Deubiquitination

[edit]Several deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) modulate p53 stability by removing ubiquitin chains. USP7, also known as HAUSP, can deubiquitinate both p53 and MDM2. In unstressed cells, HAUSP preferentially stabilizes MDM2, and its depletion may paradoxically increase p53 levels. USP42 is another DUB that stabilizes p53 and enhances its ability to respond to stress.[64] USP10 operates primarily in the cytoplasm, where it counteracts MDM2 by directly deubiquitinating p53. After DNA damage, USP10 translocates to the nucleus and further stabilizes p53. It does not interact with MDM2.[65]

Post-translational modifications and cofactors

[edit]Phosphorylation of the N-terminus not only prevents MDM2 binding but also facilitates the recruitment of cofactors. Pin1 enhances conformational changes in p53, while p300 and PCAF acetylate the C-terminus, exposing the DNA-binding domain and enhancing transcriptional activation. Conversely, deacetylases such as Sirt1 and Sirt7 remove these modifications, suppressing apoptosis and promoting cell survival.[66] Some oncogenes can also activate p53 indirectly by inhibiting MDM2.[67]

Dynamics

[edit]Both experimental evidence and mathematical modeling indicate that p53 levels oscillate over time in response to cellular signals. These oscillations become more pronounced in the presence of DNA damage, such as double-stranded breaks or UV exposure. Modeling approaches also help illustrate how mutations in p53 isoforms affect oscillatory behavior, potentially informing tissue-specific therapeutic development.[68][69][59]

Epigenetics

[edit]p53 function is also influenced by chromatin environment. The corepressor TRIM24 restricts p53 binding to epigenetically repressed loci by recognizing methylated histones. This interaction enables p53 to interpret local chromatin context and regulate gene expression in a locus-specific manner.[70][citation needed]

Role in disease

[edit]

If the TP53 gene is damaged, its ability to suppress tumors is severely compromised. Individuals who inherit only one functional copy of TP53 are predisposed to developing tumors in early adulthood, a condition known as Li–Fraumeni syndrome.[citation needed]

The TP53 gene can also be altered by mutagens—such as chemicals, radiation, or certain viruses—thereby increasing the likelihood of uncontrolled cell division. More than 50 percent of human tumors harbor a mutation or deletion of the TP53 gene.[71] Loss of p53 function leads to genomic instability, frequently resulting in an aneuploidy phenotype.[72]

Certain pathogens can also disrupt p53 activity. For example, human papillomavirus (HPV) produces the viral protein E6, which binds to and inactivates p53. In conjunction with the HPV protein E7, which inactivates the cell cycle regulator pRb, this promotes repeated cell division, clinically presenting as warts. High-risk HPV types, particularly types 16 and 18, can drive the progression from benign warts to low- or high-grade cervical dysplasia, reversible precancerous lesions. Persistent cervical infection can lead to irreversible changes, including carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical cancer. These outcomes are primarily driven by viral integration into the host genome and the continued expression of the E6 and E7 oncoproteins.[73]

Mutations

[edit]Most p53 mutations are detected by DNA sequencing. However, it is known that single missense mutations can have a large spectrum from rather mild to very severe functional effects.[69]

The large spectrum of cancer phenotypes due to mutations in the TP53 gene is also supported by the fact that different isoforms of p53 proteins have different cellular mechanisms for prevention against cancer. Mutations in TP53 can give rise to different isoforms, preventing their overall functionality in different cellular mechanisms and thereby extending the cancer phenotype from mild to severe. Recent studies show that p53 isoforms are differentially expressed in different human tissues, and the loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations within the isoforms can cause tissue-specific cancer or provide cancer stem cell potential in different tissues.[11][27][75][76] TP53 mutation also hits energy metabolism and increases glycolysis in breast cancer cells.[77]

A common human polymorphism in TP53 involves a substitution of arginine for proline at codon 72 of exon 4. Numerous studies have explored the relationship between this variation and cancer susceptibility, yielding mixed results. For instance, a 2009 meta-analysis found no association between the codon 72 polymorphism and cervical cancer risk.[78]

Other studies have identified possible associations between the codon 72 polymorphism and various cancers. A 2011 study reported that the proline variant significantly increased pancreatic cancer risk in males.[79] Another study found that proline homozygosity was associated with decreased breast cancer risk in Arab women.[80] Additional research suggested that TP53 codon 72 polymorphisms, in combination with MDM2 SNP309 and A2164G, may affect susceptibility and age of onset for non-oropharyngeal cancers in women.[81] A separate 2011 study linked the polymorphism to an increased risk of lung cancer in a Korean population.[82]

However, meta-analyses published in 2011 found no significant associations between the codon 72 variant and risks of either colorectal[83] or endometrial cancer.[84] A study of a Brazilian birth cohort found an association between the arginine variant and individuals without a family history of cancer.[85] Meanwhile, another study reported that individuals with the homozygous Pro/Pro genotype had a significantly increased risk of renal cell carcinoma.[86]

Therapeutic reactivation and gene therapy

[edit]While increasing p53 levels might appear beneficial for treating cancer, sustained p53 activation can cause premature aging.[87] A more promising approach involves restoring normal, endogenous p53 function. In some tumor types, this leads to regression via apoptosis or normalization of cell growth.[88][89]

The first commercial gene therapy, Gendicine, was approved in China in 2003 for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. It delivers a functional copy of the TP53 gene using a modified adenovirus.[90]

The small-molecule inhibitor MI-63 can bind to MDM2, blocking its interaction with p53 and reactivating p53 in cancers where its function is suppressed.[91]

Diagnostic and prognostic significance

[edit]

This image shows different patterns of p53 expression in endometrial cancers on chromogenic immunohistochemistry, whereof all except wild-type are variably termed abnormal/aberrant/mutation-type and are strongly predictive of an underlying TP53 mutation:[92]

|

Discovery

[edit]p53 was identified in 1979 by Lionel Crawford, David P. Lane, Arnold Levine, and Lloyd Old, working at Imperial Cancer Research Fund (UK), Princeton University/UMDNJ (Cancer Institute of New Jersey), and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, respectively. It had been hypothesized to exist before as the target of the SV40 virus, a strain that induced development of tumors. The name p53 is in fact a misnomer, as it describes the apparent molecular mass measured when it was first discovered, though it was later realised this was an overestimate: the correct molecular mass is only 43.7 kDa.[95]

The TP53 gene from the mouse was first cloned by Peter Chumakov of The Academy of Sciences of the USSR in 1982,[96] and independently in 1983 by Moshe Oren in collaboration with David Givol (Weizmann Institute of Science).[97][98] The human TP53 gene was cloned in 1984[7] and the full length clone in 1985.[99]

It was initially presumed to be an oncogene due to the use of mutated cDNA following purification of tumor cell mRNA. Its role as a tumor suppressor gene was revealed in 1989 by Bert Vogelstein at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Arnold Levine at Princeton University.[100][101] p53 went on to be identified as a transcription factor by Guillermina Lozano working at MD Anderson Cancer Center.[102]

Warren Maltzman, of the Waksman Institute of Rutgers University first demonstrated that TP53 was responsive to DNA damage in the form of ultraviolet radiation.[103] In a series of publications in 1991–92, Michael Kastan of Johns Hopkins University, reported that TP53 was a critical part of a signal transduction pathway that helped cells respond to DNA damage.[104]

In 1993, p53 was voted molecule of the year by Science magazine.[105]

Interactions

[edit]p53 has been shown to interact with:

- AIMP2,[106]

- ANKRD2,[107]

- APTX,[108]

- ATM,[109][110][111][112][113]

- ATR,[109][110]

- ATF3,[114][115]

- AURKA,[116]

- BAK1,[117]

- BARD1,[118]

- BLM,[119][120][121][122]

- BRCA1,[118][123][124][125][126]

- BRCA2,[118][127]

- BRCC3,[118]

- BRE,[118]

- CEBPZ,[128]

- CDC14A,[129]

- Cdk1,[130][131]

- CFLAR,[132]

- CHEK1,[119][133][134]

- CCNG1,[135]

- CREBBP,[136][137][138]

- CREB1,[138]

- Cyclin H,[139]

- CDK7,[139][140]

- DNA-PKcs,[110][133][141]

- E4F1,[142][143]

- EFEMP2,[144]

- EIF2AK2,[145]

- ELL,[146]

- EP300,[137][147][148][149]

- ERCC6,[150][151]

- GNL3,[152]

- GPS2,[153]

- GSK3B,[154]

- HSP90AA1,[155][156][157]

- HIF1A,[158][159][160][161]

- HIPK1,[162]

- HIPK2,[163][164]

- HMGB1,[165][166]

- HSPA9,[167]

- Huntingtin,[168]

- ING1,[169][170]

- ING4,[171][172]

- ING5,[171]

- IκBα,[173]

- KPNB1,[155]

- LMO3,[18]

- Mdm2,[136][174][175][176]

- MDM4,[177][178]

- MED1,[179][180]

- MAPK9,[181][182]

- MNAT1,[140]

- NDN,[183]

- NCL,[184]

- NUMB,[185]

- NF-κB,[186]

- P16,[142][176][187]

- PARC,[188]

- PARP1,[108][189]

- PIAS1,[144][190]

- CDC14B,[129]

- PIN1,[191][192]

- PLAGL1,[193]

- PLK3,[194][195]

- PRKRA,[196]

- PHB,[197]

- PML,[174][198][199]

- PSME3,[200]

- PTEN,[175]

- PTK2,[201]

- PTTG1,[202]

- RAD51,[118][203][204]

- RCHY1,[205][206]

- RELA,[186]

- Reprimo[citation needed]

- RPA1,[207][208]

- RPL11,[187]

- S100B,[209]

- SUMO1,[210][211]

- SMARCA4,[212]

- SMARCB1,[212]

- SMN1,[213]

- STAT3,[186]

- TBP,[214][215]

- TFAP2A,[216]

- TFDP1,[217]

- TIGAR,[218]

- TOP1,[219][220]

- TOP2A,[221]

- TP53BP1,[119][222][223][224][225][226][227]

- TP53BP2,[227][228]

- TOP2B,[221]

- TP53INP1,[229][230]

- TSG101,[231]

- UBE2A,[232]

- UBE2I,[144][210][233][234]

- UBC,[106][200][211][235][236][237][238][239]

- USP7,[240]

- USP10,[65]

- WRN,[122][241]

- WWOX,[242]

- XPB,[150]

- YBX1,[107][243]

- YPEL3,[244]

- YWHAZ,[245]

- Zif268,[246]

- ZNF148,[247]

- SIRT1,[248]

- circRNA_014511.[249]

See also

[edit]- Eprenetapopt, a reactivator of some mutant forms of p53

- Pifithrin, an inhibitor of p53

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000141510 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000059552 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c Surget S, Khoury MP, Bourdon JC (December 2013). "Uncovering the role of p53 splice variants in human malignancy: a clinical perspective". OncoTargets and Therapy. 7: 57–68. doi:10.2147/OTT.S53876. PMC 3872270. PMID 24379683.

- ^ Toufektchan E, Toledo F (May 2018). "The Guardian of the Genome Revisited: p53 Downregulates Genes Required for Telomere Maintenance, DNA Repair, and Centromere Structure". Cancers. 10 (5): 135. doi:10.3390/cancers10050135. PMC 5977108. PMID 29734785.

- ^ a b c Matlashewski G, Lamb P, Pim D, Peacock J, Crawford L, Benchimol S (December 1984). "Isolation and characterization of a human p53 cDNA clone: expression of the human p53 gene". The EMBO Journal. 3 (13): 3257–62. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02287.x. PMC 557846. PMID 6396087.

- ^ a b Isobe M, Emanuel BS, Givol D, Oren M, Croce CM (1986). "Localization of gene for human p53 tumour antigen to band 17p13". Nature. 320 (6057): 84–5. Bibcode:1986Natur.320...84I. doi:10.1038/320084a0. PMID 3456488. S2CID 4310476.

- ^ a b Kern SE, Kinzler KW, Bruskin A, Jarosz D, Friedman P, Prives C, et al. (June 1991). "Identification of p53 as a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein". Science. 252 (5013): 1708–11. Bibcode:1991Sci...252.1708K. doi:10.1126/science.2047879. PMID 2047879. S2CID 19647885.

- ^ a b McBride OW, Merry D, Givol D (January 1986). "The gene for human p53 cellular tumor antigen is located on chromosome 17 short arm (17p13)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (1): 130–4. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83..130M. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.1.130. PMC 322805. PMID 3001719.

- ^ a b c d Bourdon JC, Fernandes K, Murray-Zmijewski F, Liu G, Diot A, Xirodimas DP, et al. (September 2005). "p53 isoforms can regulate p53 transcriptional activity". Genes & Development. 19 (18): 2122–37. doi:10.1101/gad.1339905. PMC 1221884. PMID 16131611.

- ^ Levine AJ, Lane DP, eds. (2010). The p53 family. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-830-0.

- ^ Khoury MP, Bourdon JC (April 2011). "p53 Isoforms: An Intracellular Microprocessor?". Genes Cancer. 2 (4): 453–65. doi:10.1177/1947601911408893. PMC 3135639. PMID 21779513.

- ^ May P, May E (December 1999). "Twenty years of p53 research: structural and functional aspects of the p53 protein". Oncogene. 18 (53): 7621–36. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203285. PMID 10618702.

- ^ "OrthoMaM phylogenetic marker: TP53 coding sequence". Archived from the original on 2018-03-17. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ^ Sulak M, Fong L, Mika K, Chigurupati S, Yon L, Mongan NP, et al. (September 2016). "TP53 copy number expansion is associated with the evolution of increased body size and an enhanced DNA damage response in elephants". eLife. 5 e11994. doi:10.7554/eLife.11994. PMC 5061548. PMID 27642012.

- ^ Venot C, Maratrat M, Dureuil C, Conseiller E, Bracco L, Debussche L (August 1998). "The requirement for the p53 proline-rich functional domain for mediation of apoptosis is correlated with specific PIG3 gene transactivation and with transcriptional repression". The EMBO Journal. 17 (16): 4668–79. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.16.4668. PMC 1170796. PMID 9707426.

- ^ a b Larsen S, Yokochi T, Isogai E, Nakamura Y, Ozaki T, Nakagawara A (February 2010). "LMO3 interacts with p53 and inhibits its transcriptional activity". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 392 (3): 252–7. Bibcode:2010BBRC..392..252L. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.010. PMID 19995558.

- ^ Harms KL, Chen X (March 2005). "The C terminus of p53 family proteins is a cell fate determinant". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (5): 2014–30. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.5.2014-2030.2005. PMC 549381. PMID 15713654.

- ^ Bell S, Klein C, Müller L, Hansen S, Buchner J (October 2002). "p53 contains large unstructured regions in its native state". Journal of Molecular Biology. 322 (5): 917–27. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00848-3. PMID 12367518.

- ^ Ziemer MA, Mason A, Carlson DM (September 1982). "Cell-free translations of proline-rich protein mRNAs". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 257 (18): 11176–80. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)33948-6. PMID 7107651.

- ^ a b Nicholls CD, McLure KG, Shields MA, Lee PW (April 2002). "Biogenesis of p53 involves cotranslational dimerization of monomers and posttranslational dimerization of dimers. Implications on the dominant negative effect". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (15): 12937–12945. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108815200. PMID 11805092.

- ^ a b Suri V, Lanjuin A, Rosbash M (February 1999). "TIMELESS-dependent positive and negative autoregulation in the Drosophila circadian clock". The EMBO Journal. 18 (3): 675–686. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.3.675. PMC 1171160. PMID 9927427.

- ^ a b Natan E, Hirschberg D, Morgner N, Robinson CV, Fersht AR (August 2009). "Ultraslow oligomerization equilibria of p53 and its implications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (34): 14327–14332. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10614327N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907840106. PMC 2731847. PMID 19667193.

- ^ Ho WC, Fitzgerald MX, Marmorstein R (July 2006). "Structure of the p53 core domain dimer bound to DNA". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (29): 20494–20502. doi:10.1074/jbc.M603634200. PMID 16717092.

- ^ Zhu J, Zhang S, Jiang J, Chen X (December 2000). "Definition of the p53 functional domains necessary for inducing apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (51): 39927–34. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005676200. PMID 10982799.

- ^ a b Khoury MP, Bourdon JC (April 2011). "p53 Isoforms: An Intracellular Microprocessor?". Genes & Cancer. 2 (4): 453–65. doi:10.1177/1947601911408893. PMC 3135639. PMID 21779513.

- ^ a b Janic A, Abad E, Amelio I (January 2025). "Decoding p53 tumor suppression: a crosstalk between genomic stability and epigenetic control?". Cell Death and Differentiation. 32 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1038/s41418-024-01259-9. PMC 11742645. PMID 38379088.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Gilbert SF. Developmental Biology, 10th ed. Sunderland, MA USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers. p. 588.

- ^ a b c d Engeland K (May 2022). "Cell cycle regulation: p53-p21-RB signaling". Cell Death and Differentiation. 29 (5): 946–960. doi:10.1038/s41418-022-00988-z. PMC 9090780. PMID 35361964.

- ^ a b Williams AB, Schumacher B (May 2016). "p53 in the DNA-Damage-Repair Process". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 6 (5) a026070. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a026070. PMC 4852800. PMID 27048304.

- ^ Adimoolam S, Ford JM (September 2003). "p53 and regulation of DNA damage recognition during nucleotide excision repair". DNA Repair. 2 (9): 947–54. doi:10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00087-9. PMID 12967652.

- ^ Gatz SA, Wiesmüller L (June 2006). "p53 in recombination and repair". Cell Death and Differentiation. 13 (6): 1003–16. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401903. PMID 16543940.

- ^ a b Jung YS, Qian Y, Chen X (July 2010). "Examination of the expanding pathways for the regulation of p21 expression and activity". Cellular Signalling. 22 (7): 1003–12. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.013. PMC 2860671. PMID 20100570.

- ^ Sullivan KD, Galbraith MD, Andrysik Z, Espinosa JM (January 2018). "Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by p53". Cell Death and Differentiation. 25 (1): 133–143. doi:10.1038/cdd.2017.174. PMC 5729533. PMID 29125602.

- ^ Al Bitar S, Gali-Muhtasib H (September 2019). "The Role of the Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor p21cip1/waf1 in Targeting Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutics". Cancers. 11 (10): 1475. doi:10.3390/cancers11101475. PMC 6826572. PMID 31575057.

- ^ Karimian A, Ahmadi Y, Yousefi B (June 2016). "Multiple functions of p21 in cell cycle, apoptosis and transcriptional regulation after DNA damage". DNA Repair. 42: 63–71. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.04.008. PMID 27156098.

- ^ a b Ayaz G, Yan H, Malik N, Huang J (October 2022). "An Updated View of the Roles of p53 in Embryonic Stem Cells". Stem Cells. 40 (10): 883–891. doi:10.1093/stmcls/sxac051. PMC 9585900. PMID 35904997.

- ^ a b Dolezalova D, Mraz M, Barta T, Plevova K, Vinarsky V, Holubcova Z, et al. (July 2012). "MicroRNAs regulate p21(Waf1/Cip1) protein expression and the DNA damage response in human embryonic stem cells". Stem Cells. 30 (7): 1362–72. doi:10.1002/stem.1108. PMID 22511267.

- ^ Bates S, Phillips AC, Clark PA, Stott F, Peters G, Ludwig RL, et al. (September 1998). "p14ARF links the tumour suppressors RB and p53". Nature. 395 (6698): 124–5. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..124B. doi:10.1038/25867. PMID 9744267. S2CID 4355786.

- ^ "Genome's guardian gets a tan started". New Scientist. March 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ^ Cui R, Widlund HR, Feige E, Lin JY, Wilensky DL, Igras VE, et al. (March 2007). "Central role of p53 in the suntan response and pathologic hyperpigmentation". Cell. 128 (5): 853–64. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.045. PMID 17350573.

- ^ Fu X, Wu S, Li B, Xu Y, Liu J (2020). "Functions of p53 in pluripotent stem cells". Oxford Academic. 11 (1): 71–78. doi:10.1007/s13238-019-00665-x. PMC 6949194. PMID 31691903.

- ^ a b Jain AK, Allton K, Iacovino M, Mahen E, Milczarek RJ, Zwaka TP, et al. (2012). "p53 regulates cell cycle and microRNAs to promote differentiation of human embryonic stem cells". PLOS Biology. 10 (2) e1001268. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001268. PMC 3289600. PMID 22389628.

- ^ Maimets T, Neganova I, Armstrong L, Lako M (September 2008). "Activation of p53 by nutlin leads to rapid differentiation of human embryonic stem cells". Oncogene. 27 (40): 5277–87. doi:10.1038/onc.2008.166. PMID 18521083.

- ^ ter Huurne M, Peng T, Yi G, van Mierlo G, Marks H, Stunnenberg HG (February 2020). "Critical role for P53 in regulating the cell cycle of ground state embryonic stem cells". Stem Cell Reports. 14 (2): 175–183. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.01.001. PMC 7013234. PMID 32004494.

- ^ Das B, Bayat-Mokhtari R, Tsui M, Lotfi S, Tsuchida R, Felsher DW, et al. (August 2012). "HIF-2α suppresses p53 to enhance the stemness and regenerative potential of human embryonic stem cells". Stem Cells. 30 (8): 1685–95. doi:10.1002/stem.1142. PMC 3584519. PMID 22689594.

- ^ Lake BB, Fink J, Klemetsaune L, Fu X, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, et al. (May 2012). "Context-dependent enhancement of induced pluripotent stem cell reprogramming by silencing Puma". Stem Cells. 30 (5): 888–97. doi:10.1002/stem.1054. PMC 3531606. PMID 22311782.

- ^ Marión RM, Strati K, Li H, Murga M, Blanco R, Ortega S, et al. (August 2009). "A p53-mediated DNA damage response limits reprogramming to ensure iPS cell genomic integrity". Nature. 460 (7259): 1149–53. Bibcode:2009Natur.460.1149M. doi:10.1038/nature08287. PMC 3624089. PMID 19668189.

- ^ Yun MH, Gates PB, Brockes JP (October 2013). "Regulation of p53 is critical for vertebrate limb regeneration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (43): 17392–7. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11017392Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1310519110. PMC 3808590. PMID 24101460.

- ^ Aloni-Grinstein R, Shetzer Y, Kaufman T, Rotter V (August 2014). "p53: the barrier to cancer stem cell formation". FEBS Letters. 588 (16): 2580–9. Bibcode:2014FEBSL.588.2580A. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.011. PMID 24560790. S2CID 37901173.

- ^ a b Babaei G, Aliarab A, Asghari Vostakolaei M, Hotelchi M, Neisari R, Gholizadeh-Ghaleh Aziz S, et al. (November 2021). "Crosslink between p53 and metastasis: focus on epithelial-mesenchymal transition, cancer stem cell, angiogenesis, autophagy, and anoikis". Molecular Biology Reports. 48 (11): 7545–7557. doi:10.1007/s11033-021-06706-1. PMID 34519942. S2CID 237506513.

- ^ Teodoro JG, Evans SK, Green MR (November 2007). "Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by p53: a new role for the guardian of the genome". Journal of Molecular Medicine (Review). 85 (11): 1175–1186. doi:10.1007/s00109-007-0221-2. PMID 17589818. S2CID 10094554.

- ^ Assadian S, El-Assaad W, Wang XQ, Gannon PO, Barrès V, Latour M, et al. (March 2012). "p53 inhibits angiogenesis by inducing the production of Arresten". Cancer Research. 72 (5): 1270–1279. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2348. PMID 22253229.

- ^ Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ (November 2007). "p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF". Nature. 450 (7170): 721–4. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..721H. doi:10.1038/nature05993. PMID 18046411. S2CID 4357527.

- ^ Borchsenius SN, Daks A, Fedorova O, Chernova O, Barlev NA (January 2018). "Effects of mycoplasma infection on the host organism response via p53/NF-κB signaling". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 234 (1): 171–180. doi:10.1002/jcp.26781. PMID 30146800.

- ^ Bykov VJ, Eriksson SE, Bianchi J, Wiman KG (February 2018). "Targeting mutant p53 for efficient cancer therapy". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 18 (2): 89–102. doi:10.1038/nrc.2017.109. PMID 29242642. S2CID 4552678.

- ^ Geva-Zatorsky N, Rosenfeld N, Itzkovitz S, Milo R, Sigal A, Dekel E, et al. (June 2006). "Oscillations and variability in the p53 system". Molecular Systems Biology. 2 2006.0033. doi:10.1038/msb4100068. PMC 1681500. PMID 16773083.

- ^ a b Proctor CJ, Gray DA (August 2008). "Explaining oscillations and variability in the p53-Mdm2 system". BMC Systems Biology. 2 (75) 75. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-2-75. PMC 2553322. PMID 18706112.

- ^ Chong KH, Samarasinghe S, Kulasiri D (December 2013). "Mathematical modelling of p53 basal dynamics and DNA damage response". C-fACS. 259 (20th International Congress on Mathematical Modelling and Simulation): 670–6. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2014.10.010. PMID 25433195.

- ^ Purvis JE, Karhohs KW, Mock C, Batchelor E, Loewer A, Lahav G (June 2012). "p53 dynamics control cell fate". Science. 336 (6087): 1440–1444. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1440P. doi:10.1126/science.1218351. PMC 4162876. PMID 22700930.

- ^ Han ES, Muller FL, Pérez VI, Qi W, Liang H, Xi L, et al. (June 2008). "The in vivo gene expression signature of oxidative stress". Physiological Genomics. 34 (1): 112–126. doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00239.2007. PMC 2532791. PMID 18445702.

- ^ Grajales-Reyes GE, Colonna M (August 2020). "Interferon responses in viral pneumonias". Science. 369 (6504): 626–627. Bibcode:2020Sci...369..626G. doi:10.1126/science.abd2208. PMID 32764056.

- ^ Hock AK, Vigneron AM, Carter S, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH (November 2011). "Regulation of p53 stability and function by the deubiquitinating enzyme USP42". The EMBO Journal. 30 (24): 4921–30. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.419. PMC 3243628. PMID 22085928.

- ^ a b Yuan J, Luo K, Zhang L, Cheville JC, Lou Z (February 2010). "USP10 Regulates p53 Localization and Stability by Deubiquitinating p53". Cell. 140 (3): 384–396. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.032. PMC 2820153. PMID 20096447.

- ^ Vakhrusheva O, Smolka C, Gajawada P, Kostin S, Boettger T, Kubin T, et al. (March 2008). "Sirt7 increases stress resistance of cardiomyocytes and prevents apoptosis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy in mice". Circulation Research. 102 (6): 703–10. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164558. PMID 18239138.

- ^ Inoue K, Fry EA, Frazier DP (April 2016). "Transcription factors that interact with p53 and Mdm2". International Journal of Cancer. 138 (7): 1577–85. doi:10.1002/ijc.29663. PMC 4698088. PMID 26132471.

- ^ Ribeiro AS, Charlebois DA, Lloyd-Price J (December 2007). "CellLine, a stochastic cell lineage simulator". Bioinformatics. 23 (24): 3409–3411. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm491. PMID 17928303.

- ^ a b Bullock AN, Henckel J, DeDecker BS, Johnson CM, Nikolova PV, Proctor MR, et al. (December 1997). "Thermodynamic stability of wild-type and mutant p53 core domain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (26): 14338–42. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9414338B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.26.14338. PMC 24967. PMID 9405613.

- ^ Isbel L, Iskar M, Durdu S, Grand RS, Weiss J, Hietter-Pfeiffer E, et al. (June 2023). "Readout of histone methylation by Trim24 locally restricts chromatin opening by p53". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 30 (7): 948–57. doi:10.1038/s41594-023-01021-8. hdl:2440/139184. PMC 10352137. PMID 37386214.

- ^ Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC (July 1991). "p53 mutations in human cancers". Science. 253 (5015): 49–53. Bibcode:1991Sci...253...49H. doi:10.1126/science.1905840. PMID 1905840. S2CID 38527914.

- ^ Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, Baranov E, Hoffman RM, Lowe SW (April 2002). "Dissecting p53 tumor suppressor functions in vivo". Cancer Cell. 1 (3): 289–98. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00047-8. PMID 12086865.

- ^ Angeletti PC, Zhang L, Wood C (2008). "The Viral Etiology of AIDS-Associated Malignancies". HIV-1: Molecular Biology and Pathogenesis. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 56. pp. 509–57. doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(07)56016-3. ISBN 978-0-12-373601-7. PMC 2149907. PMID 18086422.

- ^ a b Butera A, Amelio I (July 2024). "Deciphering the significance of p53 mutant proteins". Trends in Cell Biology. 35 (3): 258–268. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2024.06.003. PMID 38960851.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Avery-Kiejda KA, Morten B, Wong-Brown MW, Mathe A, Scott RJ (March 2014). "The relative mRNA expression of p53 isoforms in breast cancer is associated with clinical features and outcome". Carcinogenesis. 35 (3): 586–96. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgt411. PMID 24336193.

- ^ Arsic N, Gadea G, Lagerqvist EL, Busson M, Cahuzac N, Brock C, et al. (April 2015). "The p53 isoform Δ133p53β promotes cancer stem cell potential". Stem Cell Reports. 4 (4): 531–40. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.001. PMC 4400643. PMID 25754205.

- ^ Harami-Papp H, Pongor LS, Munkácsy G, Horváth G, Nagy ÁM, Ambrus A, et al. (October 2016). "TP53 mutation hits energy metabolism and increases glycolysis in breast cancer". Oncotarget. 7 (41): 67183–67195. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.11594. PMC 5341867. PMID 27582538.

- ^ Klug SJ, Ressing M, Koenig J, Abba MC, Agorastos T, Brenna SM, et al. (August 2009). "TP53 codon 72 polymorphism and cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of individual data from 49 studies". The Lancet. Oncology. 10 (8): 772–84. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70187-1. PMID 19625214.

- ^ Sonoyama T, Sakai A, Mita Y, Yasuda Y, Kawamoto H, Yagi T, et al. (2011). "TP53 codon 72 polymorphism is associated with pancreatic cancer risk in males, smokers and drinkers". Molecular Medicine Reports. 4 (3): 489–95. doi:10.3892/mmr.2011.449. PMID 21468597.

- ^ Alawadi S, Ghabreau L, Alsaleh M, Abdulaziz Z, Rafeek M, Akil N, et al. (September 2011). "P53 gene polymorphisms and breast cancer risk in Arab women". Medical Oncology. 28 (3): 709–15. doi:10.1007/s12032-010-9505-4. PMID 20443084. S2CID 207372095.

- ^ Yu H, Huang YJ, Liu Z, Wang LE, Li G, Sturgis EM, et al. (September 2011). "Effects of MDM2 promoter polymorphisms and p53 codon 72 polymorphism on risk and age at onset of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck". Molecular Carcinogenesis. 50 (9): 697–706. doi:10.1002/mc.20806. PMC 3142329. PMID 21656578.

- ^ Piao JM, Kim HN, Song HR, Kweon SS, Choi JS, Yun WJ, et al. (September 2011). "p53 codon 72 polymorphism and the risk of lung cancer in a Korean population". Lung Cancer. 73 (3): 264–7. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.12.017. PMID 21316118.

- ^ Wang JJ, Zheng Y, Sun L, Wang L, Yu PB, Dong JH, et al. (November 2011). "TP53 codon 72 polymorphism and colorectal cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis". Molecular Biology Reports. 38 (8): 4847–53. doi:10.1007/s11033-010-0619-8. PMID 21140221. S2CID 11730631.

- ^ Jiang DK, Yao L, Ren WH, Wang WZ, Peng B, Yu L (December 2011). "TP53 Arg72Pro polymorphism and endometrial cancer risk: a meta-analysis". Medical Oncology. 28 (4): 1129–35. doi:10.1007/s12032-010-9597-x. PMID 20552298. S2CID 32990396.

- ^ Thurow HS, Haack R, Hartwig FP, Oliveira IO, Dellagostin OA, Gigante DP, et al. (December 2011). "TP53 gene polymorphism: importance to cancer, ethnicity and birth weight in a Brazilian cohort". Journal of Biosciences. 36 (5): 823–31. doi:10.1007/s12038-011-9147-5. PMID 22116280. S2CID 23027087.

- ^ Huang CY, Su CT, Chu JS, Huang SP, Pu YS, Yang HY, et al. (December 2011). "The polymorphisms of P53 codon 72 and MDM2 SNP309 and renal cell carcinoma risk in a low arsenic exposure area". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 257 (3): 349–55. Bibcode:2011ToxAP.257..349H. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2011.09.018. PMID 21982800.

- ^ Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, et al. (January 2002). "p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes". Nature. 415 (6867): 45–53. Bibcode:2002Natur.415...45T. doi:10.1038/415045a. PMID 11780111. S2CID 749047.

- ^ Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, et al. (February 2007). "Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo". Nature. 445 (7128): 661–5. doi:10.1038/nature05541. PMID 17251932. S2CID 4373520.

- ^ Herce HD, Deng W, Helma J, Leonhardt H, Cardoso MC (2013). "Visualization and targeted disruption of protein interactions in living cells". Nature Communications. 4 2660. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2660H. doi:10.1038/ncomms3660. PMC 3826628. PMID 24154492.

- ^ Pearson S, Jia H, Kandachi K (January 2004). "China approves first gene therapy". Nature Biotechnology. 22 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1038/nbt0104-3. PMC 7097065. PMID 14704685.

- ^ Canner JA, Sobo M, Ball S, Hutzen B, DeAngelis S, Willis W, et al. (September 2009). "MI-63: a novel small-molecule inhibitor targets MDM2 and induces apoptosis in embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cells with wild-type p53". British Journal of Cancer. 101 (5): 774–81. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605199. PMC 2736841. PMID 19707204.

- ^ Köbel M, Ronnett BM, Singh N, Soslow RA, Gilks CB, McCluggage WG (January 2019). "Interpretation of P53 Immunohistochemistry in Endometrial Carcinomas: Toward Increased Reproducibility". International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 38 (Suppl 1): S123 – S131. doi:10.1097/PGP.0000000000000488. PMC 6127005. PMID 29517499.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Image is taken from following source, with some modification by Mikael Häggström, MD:

- Schallenberg S, Plage H, Hofbauer S, Furlano K, Weinberger S, Bruch PG (2023). "Altered p53/p16 expression is linked to urothelial carcinoma progression but largely unrelated to prognosis in muscle-invasive tumors". Acta Oncol. 62 (12): 1880–1889. doi:10.1080/0284186X.2023.2277344. PMID 37938166. - ^ Kalantari MR, Ahmadnia H (2007). "P53 overexpression in bladder urothelial neoplasms: new aspect of World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology classification". Urol J. 4 (4): 230–3. PMID 18270948.

- ^ Levine AJ, Oren M (October 2009). "The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 9 (10): 749–758. doi:10.1038/nrc2723. PMC 2771725. PMID 19776744.

- ^ Chumakov PM, Iotsova VS, Georgiev GP (1982). "[Isolation of a plasmid clone containing the mRNA sequence for mouse nonviral T-antigen]". Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian). 267 (5): 1272–5. PMID 6295732.

- ^ Oren M, Levine AJ (January 1983). "Molecular cloning of a cDNA specific for the murine p53 cellular tumor antigen". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (1): 56–9. Bibcode:1983PNAS...80...56O. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.1.56. PMC 393308. PMID 6296874.

- ^ Zakut-Houri R, Oren M, Bienz B, Lavie V, Hazum S, Givol D (1983). "A single gene and a pseudogene for the cellular tumour antigen p53". Nature. 306 (5943): 594–7. Bibcode:1983Natur.306..594Z. doi:10.1038/306594a0. PMID 6646235. S2CID 4325094.

- ^ Zakut-Houri R, Bienz-Tadmor B, Givol D, Oren M (May 1985). "Human p53 cellular tumor antigen: cDNA sequence and expression in COS cells". The EMBO Journal. 4 (5): 1251–5. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03768.x. PMC 554332. PMID 4006916.

- ^ Baker SJ, Fearon ER, Nigro JM, Hamilton SR, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, et al. (April 1989). "Chromosome 17 deletions and p53 gene mutations in colorectal carcinomas". Science. 244 (4901): 217–21. Bibcode:1989Sci...244..217B. doi:10.1126/science.2649981. PMID 2649981.

- ^ Finlay CA, Hinds PW, Levine AJ (June 1989). "The p53 proto-oncogene can act as a suppressor of transformation". Cell. 57 (7): 1083–93. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(89)90045-7. PMID 2525423.

- ^ Raycroft L, Wu HY, Lozano G (August 1990). "Transcriptional activation by wild-type but not transforming mutants of the p53 anti-oncogene". Science. 249 (4972): 1049–1051. Bibcode:1990Sci...249.1049R. doi:10.1126/science.2144364. PMC 2935288. PMID 2144364.

- ^ Maltzman W, Czyzyk L (September 1984). "UV irradiation stimulates levels of p53 cellular tumor antigen in nontransformed mouse cells". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 4 (9): 1689–94. doi:10.1128/mcb.4.9.1689. PMC 368974. PMID 6092932.

- ^ Kastan MB, Kuerbitz SJ (December 1993). "Control of G1 arrest after DNA damage". Environmental Health Perspectives. 101 (Suppl 5): 55–8. doi:10.2307/3431842. JSTOR 3431842. PMC 1519427. PMID 8013425.

- ^ Koshland DE (December 1993). "Molecule of the year". Science. 262 (5142): 1953. Bibcode:1993Sci...262.1953K. doi:10.1126/science.8266084. PMID 8266084.

- ^ a b Han JM, Park BJ, Park SG, Oh YS, Choi SJ, Lee SW, et al. (August 2008). "AIMP2/p38, the scaffold for the multi-tRNA synthetase complex, responds to genotoxic stresses via p53". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (32): 11206–11. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511206H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800297105. PMC 2516205. PMID 18695251.

- ^ a b Kojic S, Medeot E, Guccione E, Krmac H, Zara I, Martinelli V, et al. (May 2004). "The Ankrd2 protein, a link between the sarcomere and the nucleus in skeletal muscle". Journal of Molecular Biology. 339 (2): 313–25. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.071. PMID 15136035.

- ^ a b Gueven N, Becherel OJ, Kijas AW, Chen P, Howe O, Rudolph JH, et al. (May 2004). "Aprataxin, a novel protein that protects against genotoxic stress". Human Molecular Genetics. 13 (10): 1081–93. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh122. PMID 15044383.

- ^ a b Fabbro M, Savage K, Hobson K, Deans AJ, Powell SN, McArthur GA, et al. (July 2004). "BRCA1-BARD1 complexes are required for p53Ser-15 phosphorylation and a G1/S arrest following ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (30): 31251–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405372200. PMID 15159397.

- ^ a b c Kim ST, Lim DS, Canman CE, Kastan MB (December 1999). "Substrate specificities and identification of putative substrates of ATM kinase family members". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (53): 37538–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.53.37538. PMID 10608806.

- ^ Kang J, Ferguson D, Song H, Bassing C, Eckersdorff M, Alt FW, et al. (January 2005). "Functional interaction of H2AX, NBS1, and p53 in ATM-dependent DNA damage responses and tumor suppression". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (2): 661–70. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.2.661-670.2005. PMC 543410. PMID 15632067.

- ^ Khanna KK, Keating KE, Kozlov S, Scott S, Gatei M, Hobson K, et al. (December 1998). "ATM associates with and phosphorylates p53: mapping the region of interaction". Nature Genetics. 20 (4): 398–400. doi:10.1038/3882. PMID 9843217. S2CID 23994762.

- ^ Westphal CH, Schmaltz C, Rowan S, Elson A, Fisher DE, Leder P (May 1997). "Genetic interactions between atm and p53 influence cellular proliferation and irradiation-induced cell cycle checkpoints". Cancer Research. 57 (9): 1664–7. PMID 9135004.

- ^ Stelzl U, Worm U, Lalowski M, Haenig C, Brembeck FH, Goehler H, et al. (September 2005). "A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome". Cell. 122 (6): 957–68. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0010-8592-0. PMID 16169070.

- ^ Yan C, Wang H, Boyd DD (March 2002). "ATF3 represses 72-kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-2) expression by antagonizing p53-dependent trans-activation of the collagenase promoter". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (13): 10804–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112069200. PMID 11792711.

- ^ Chen SS, Chang PC, Cheng YW, Tang FM, Lin YS (September 2002). "Suppression of the STK15 oncogenic activity requires a transactivation-independent p53 function". The EMBO Journal. 21 (17): 4491–9. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf409. PMC 126178. PMID 12198151.

- ^ Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME, George DL (May 2004). "Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (5): 443–50. doi:10.1038/ncb1123. PMID 15077116. S2CID 43063712.

- ^ a b c d e f Dong Y, Hakimi MA, Chen X, Kumaraswamy E, Cooch NS, Godwin AK, et al. (November 2003). "Regulation of BRCC, a holoenzyme complex containing BRCA1 and BRCA2, by a signalosome-like subunit and its role in DNA repair". Molecular Cell. 12 (5): 1087–99. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00424-6. PMID 14636569.

- ^ a b c Sengupta S, Robles AI, Linke SP, Sinogeeva NI, Zhang R, Pedeux R, et al. (September 2004). "Functional interaction between BLM helicase and 53BP1 in a Chk1-mediated pathway during S-phase arrest". The Journal of Cell Biology. 166 (6): 801–13. doi:10.1083/jcb.200405128. PMC 2172115. PMID 15364958.

- ^ Wang XW, Tseng A, Ellis NA, Spillare EA, Linke SP, Robles AI, et al. (August 2001). "Functional interaction of p53 and BLM DNA helicase in apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (35): 32948–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M103298200. PMID 11399766.

- ^ Garkavtsev IV, Kley N, Grigorian IA, Gudkov AV (December 2001). "The Bloom syndrome protein interacts and cooperates with p53 in regulation of transcription and cell growth control". Oncogene. 20 (57): 8276–80. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205120. PMID 11781842. S2CID 13084911.

- ^ a b Yang Q, Zhang R, Wang XW, Spillare EA, Linke SP, Subramanian D, et al. (August 2002). "The processing of Holliday junctions by BLM and WRN helicases is regulated by p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (35): 31980–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M204111200. hdl:10026.1/10341. PMID 12080066.

- ^ Abramovitch S, Werner H (2003). "Functional and physical interactions between BRCA1 and p53 in transcriptional regulation of the IGF-IR gene". Hormone and Metabolic Research. 35 (11–12): 758–62. doi:10.1055/s-2004-814154. PMID 14710355. S2CID 20898175.

- ^ Ouchi T, Monteiro AN, August A, Aaronson SA, Hanafusa H (March 1998). "BRCA1 regulates p53-dependent gene expression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (5): 2302–6. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.2302O. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2302. PMC 19327. PMID 9482880.

- ^ Chai YL, Cui J, Shao N, Shyam E, Reddy P, Rao VN (January 1999). "The second BRCT domain of BRCA1 proteins interacts with p53 and stimulates transcription from the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter". Oncogene. 18 (1): 263–8. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202323. PMID 9926942. S2CID 7462625.

- ^ Zhang H, Somasundaram K, Peng Y, Tian H, Zhang H, Bi D, et al. (April 1998). "BRCA1 physically associates with p53 and stimulates its transcriptional activity". Oncogene. 16 (13): 1713–21. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201932. PMID 9582019. S2CID 24616900.

- ^ Marmorstein LY, Ouchi T, Aaronson SA (November 1998). "The BRCA2 gene product functionally interacts with p53 and RAD51". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (23): 13869–74. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9513869M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13869. PMC 24938. PMID 9811893.

- ^ Uramoto H, Izumi H, Nagatani G, Ohmori H, Nagasue N, Ise T, et al. (April 2003). "Physical interaction of tumour suppressor p53/p73 with CCAAT-binding transcription factor 2 (CTF2) and differential regulation of human high-mobility group 1 (HMG1) gene expression". The Biochemical Journal. 371 (Pt 2): 301–10. doi:10.1042/BJ20021646. PMC 1223307. PMID 12534345.

- ^ a b Li L, Ljungman M, Dixon JE (January 2000). "The human Cdc14 phosphatases interact with and dephosphorylate the tumor suppressor protein p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (4): 2410–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.4.2410. PMID 10644693.

- ^ Luciani MG, Hutchins JR, Zheleva D, Hupp TR (July 2000). "The C-terminal regulatory domain of p53 contains a functional docking site for cyclin A". Journal of Molecular Biology. 300 (3): 503–18. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3830. PMID 10884347.

- ^ Ababneh M, Götz C, Montenarh M (May 2001). "Downregulation of the cdc2/cyclin B protein kinase activity by binding of p53 to p34(cdc2)". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 283 (2): 507–12. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.4792. PMID 11327730.

- ^ Abedini MR, Muller EJ, Brun J, Bergeron R, Gray DA, Tsang BK (June 2008). "Cisplatin induces p53-dependent FLICE-like inhibitory protein ubiquitination in ovarian cancer cells". Cancer Research. 68 (12): 4511–7. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0673. PMID 18559494.

- ^ a b Goudelock DM, Jiang K, Pereira E, Russell B, Sanchez Y (August 2003). "Regulatory interactions between the checkpoint kinase Chk1 and the proteins of the DNA-dependent protein kinase complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (32): 29940–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301765200. PMID 12756247.

- ^ Tian H, Faje AT, Lee SL, Jorgensen TJ (2002). "Radiation-induced phosphorylation of Chk1 at S345 is associated with p53-dependent cell cycle arrest pathways". Neoplasia. 4 (2): 171–80. doi:10.1038/sj.neo.7900219. PMC 1550321. PMID 11896572.

- ^ Zhao L, Samuels T, Winckler S, Korgaonkar C, Tompkins V, Horne MC, et al. (January 2003). "Cyclin G1 has growth inhibitory activity linked to the ARF-Mdm2-p53 and pRb tumor suppressor pathways". Molecular Cancer Research. 1 (3): 195–206. PMID 12556559.

- ^ a b Ito A, Kawaguchi Y, Lai CH, Kovacs JJ, Higashimoto Y, Appella E, et al. (November 2002). "MDM2-HDAC1-mediated deacetylation of p53 is required for its degradation". The EMBO Journal. 21 (22): 6236–45. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf616. PMC 137207. PMID 12426395.

- ^ a b Livengood JA, Scoggin KE, Van Orden K, McBryant SJ, Edayathumangalam RS, Laybourn PJ, et al. (March 2002). "p53 Transcriptional activity is mediated through the SRC1-interacting domain of CBP/p300". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (11): 9054–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108870200. PMID 11782467.

- ^ a b Giebler HA, Lemasson I, Nyborg JK (July 2000). "p53 recruitment of CREB binding protein mediated through phosphorylated CREB: a novel pathway of tumor suppressor regulation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 20 (13): 4849–58. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.13.4849-4858.2000. PMC 85936. PMID 10848610.

- ^ a b Schneider E, Montenarh M, Wagner P (November 1998). "Regulation of CAK kinase activity by p53". Oncogene. 17 (21): 2733–41. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202504. PMID 9840937. S2CID 6281777.

- ^ a b Ko LJ, Shieh SY, Chen X, Jayaraman L, Tamai K, Taya Y, et al. (December 1997). "p53 is phosphorylated by CDK7-cyclin H in a p36MAT1-dependent manner". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 17 (12): 7220–9. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.12.7220. PMC 232579. PMID 9372954.

- ^ Yavuzer U, Smith GC, Bliss T, Werner D, Jackson SP (July 1998). "DNA end-independent activation of DNA-PK mediated via association with the DNA-binding protein C1D". Genes & Development. 12 (14): 2188–99. doi:10.1101/gad.12.14.2188. PMC 317006. PMID 9679063.

- ^ a b Rizos H, Diefenbach E, Badhwar P, Woodruff S, Becker TM, Rooney RJ, et al. (February 2003). "Association of p14ARF with the p120E4F transcriptional repressor enhances cell cycle inhibition". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (7): 4981–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M210978200. PMID 12446718.

- ^ Sandy P, Gostissa M, Fogal V, Cecco LD, Szalay K, Rooney RJ, et al. (January 2000). "p53 is involved in the p120E4F-mediated growth arrest". Oncogene. 19 (2): 188–99. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203250. PMID 10644996.

- ^ a b c Gallagher WM, Argentini M, Sierra V, Bracco L, Debussche L, Conseiller E (June 1999). "MBP1: a novel mutant p53-specific protein partner with oncogenic properties". Oncogene. 18 (24): 3608–16. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202937. PMID 10380882.

- ^ Cuddihy AR, Wong AH, Tam NW, Li S, Koromilas AE (April 1999). "The double-stranded RNA activated protein kinase PKR physically associates with the tumor suppressor p53 protein and phosphorylates human p53 on serine 392 in vitro". Oncogene. 18 (17): 2690–702. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202620. PMID 10348343. S2CID 22467088.

- ^ Shinobu N, Maeda T, Aso T, Ito T, Kondo T, Koike K, et al. (June 1999). "Physical interaction and functional antagonism between the RNA polymerase II elongation factor ELL and p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (24): 17003–10. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.24.17003. PMID 10358050.

- ^ Grossman SR, Perez M, Kung AL, Joseph M, Mansur C, Xiao ZX, et al. (October 1998). "p300/MDM2 complexes participate in MDM2-mediated p53 degradation". Molecular Cell. 2 (4): 405–15. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80140-9. PMID 9809062.

- ^ An W, Kim J, Roeder RG (June 2004). "Ordered cooperative functions of PRMT1, p300, and CARM1 in transcriptional activation by p53". Cell. 117 (6): 735–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.009. PMID 15186775.

- ^ Pastorcic M, Das HK (November 2000). "Regulation of transcription of the human presenilin-1 gene by ets transcription factors and the p53 protooncogene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (45): 34938–45. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005411200. PMID 10942770.

- ^ a b Wang XW, Yeh H, Schaeffer L, Roy R, Moncollin V, Egly JM, et al. (June 1995). "p53 modulation of TFIIH-associated nucleotide excision repair activity". Nature Genetics. 10 (2): 188–95. doi:10.1038/ng0695-188. hdl:1765/54884. PMID 7663514. S2CID 38325851.

- ^ Yu A, Fan HY, Liao D, Bailey AD, Weiner AM (May 2000). "Activation of p53 or loss of the Cockayne syndrome group B repair protein causes metaphase fragility of human U1, U2, and 5S genes". Molecular Cell. 5 (5): 801–10. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80320-2. PMID 10882116.

- ^ Tsai RY, McKay RD (December 2002). "A nucleolar mechanism controlling cell proliferation in stem cells and cancer cells". Genes & Development. 16 (23): 2991–3003. doi:10.1101/gad.55671. PMC 187487. PMID 12464630.

- ^ Peng YC, Kuo F, Breiding DE, Wang YF, Mansur CP, Androphy EJ (September 2001). "AMF1 (GPS2) modulates p53 transactivation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 21 (17): 5913–24. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.17.5913-5924.2001. PMC 87310. PMID 11486030.

- ^ Watcharasit P, Bijur GN, Zmijewski JW, Song L, Zmijewska A, Chen X, et al. (June 2002). "Direct, activating interaction between glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and p53 after DNA damage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (12): 7951–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.7951W. doi:10.1073/pnas.122062299. PMC 123001. PMID 12048243.

- ^ a b Akakura S, Yoshida M, Yoneda Y, Horinouchi S (May 2001). "A role for Hsc70 in regulating nucleocytoplasmic transport of a temperature-sensitive p53 (p53Val-135)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (18): 14649–57. doi:10.1074/jbc.M100200200. PMID 11297531.

- ^ Wang C, Chen J (January 2003). "Phosphorylation and hsp90 binding mediate heat shock stabilization of p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (3): 2066–71. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206697200. PMID 12427754.

- ^ Peng Y, Chen L, Li C, Lu W, Chen J (November 2001). "Inhibition of MDM2 by hsp90 contributes to mutant p53 stabilization". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (44): 40583–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.M102817200. PMID 11507088.

- ^ Chen D, Li M, Luo J, Gu W (April 2003). "Direct interactions between HIF-1 alpha and Mdm2 modulate p53 function". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (16): 13595–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200694200. PMID 12606552.

- ^ Ravi R, Mookerjee B, Bhujwalla ZM, Sutter CH, Artemov D, Zeng Q, et al. (January 2000). "Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha". Genes & Development. 14 (1): 34–44. doi:10.1101/gad.14.1.34. PMC 316350. PMID 10640274.

- ^ Hansson LO, Friedler A, Freund S, Rudiger S, Fersht AR (August 2002). "Two sequence motifs from HIF-1alpha bind to the DNA-binding site of p53". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (16): 10305–9. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9910305H. doi:10.1073/pnas.122347199. PMC 124909. PMID 12124396.

- ^ An WG, Kanekal M, Simon MC, Maltepe E, Blagosklonny MV, Neckers LM (March 1998). "Stabilization of wild-type p53 by hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha". Nature. 392 (6674): 405–8. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..405A. doi:10.1038/32925. PMID 9537326. S2CID 4423081.

- ^ Kondo S, Lu Y, Debbas M, Lin AW, Sarosi I, Itie A, et al. (April 2003). "Characterization of cells and gene-targeted mice deficient for the p53-binding kinase homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1 (HIPK1)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (9): 5431–6. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.5431K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0530308100. PMC 154362. PMID 12702766.

- ^ Hofmann TG, Möller A, Sirma H, Zentgraf H, Taya Y, Dröge W, et al. (January 2002). "Regulation of p53 activity by its interaction with homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2". Nature Cell Biology. 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1038/ncb715. PMID 11740489. S2CID 37789883.

- ^ Kim EJ, Park JS, Um SJ (August 2002). "Identification and characterization of HIPK2 interacting with p73 and modulating functions of the p53 family in vivo". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (35): 32020–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M200153200. PMID 11925430.

- ^ Imamura T, Izumi H, Nagatani G, Ise T, Nomoto M, Iwamoto Y, et al. (March 2001). "Interaction with p53 enhances binding of cisplatin-modified DNA by high mobility group 1 protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (10): 7534–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008143200. PMID 11106654.

- ^ Dintilhac A, Bernués J (March 2002). "HMGB1 interacts with many apparently unrelated proteins by recognizing short amino acid sequences". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (9): 7021–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108417200. hdl:10261/112516. PMID 11748221.

- ^ Wadhwa R, Yaguchi T, Hasan MK, Mitsui Y, Reddel RR, Kaul SC (April 2002). "Hsp70 family member, mot-2/mthsp70/GRP75, binds to the cytoplasmic sequestration domain of the p53 protein". Experimental Cell Research. 274 (2): 246–53. doi:10.1006/excr.2002.5468. PMID 11900485.

- ^ Steffan JS, Kazantsev A, Spasic-Boskovic O, Greenwald M, Zhu YZ, Gohler H, et al. (June 2000). "The Huntington's disease protein interacts with p53 and CREB-binding protein and represses transcription". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (12): 6763–8. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.6763S. doi:10.1073/pnas.100110097. PMC 18731. PMID 10823891.

- ^ Leung KM, Po LS, Tsang FC, Siu WY, Lau A, Ho HT, et al. (September 2002). "The candidate tumor suppressor ING1b can stabilize p53 by disrupting the regulation of p53 by MDM2". Cancer Research. 62 (17): 4890–3. PMID 12208736.

- ^ Garkavtsev I, Grigorian IA, Ossovskaya VS, Chernov MV, Chumakov PM, Gudkov AV (January 1998). "The candidate tumour suppressor p33ING1 cooperates with p53 in cell growth control". Nature. 391 (6664): 295–8. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..295G. doi:10.1038/34675. PMID 9440695. S2CID 4429461.

- ^ a b Shiseki M, Nagashima M, Pedeux RM, Kitahama-Shiseki M, Miura K, Okamura S, et al. (May 2003). "p29ING4 and p28ING5 bind to p53 and p300, and enhance p53 activity". Cancer Research. 63 (10): 2373–8. PMID 12750254.

- ^ Tsai KW, Tseng HC, Lin WC (October 2008). "Two wobble-splicing events affect ING4 protein subnuclear localization and degradation". Experimental Cell Research. 314 (17): 3130–41. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.002. PMID 18775696.

- ^ Chang NS (March 2002). "The non-ankyrin C terminus of Ikappa Balpha physically interacts with p53 in vivo and dissociates in response to apoptotic stress, hypoxia, DNA damage, and transforming growth factor-beta 1-mediated growth suppression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (12): 10323–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106607200. PMID 11799106.

- ^ a b Kurki S, Latonen L, Laiho M (October 2003). "Cellular stress and DNA damage invoke temporally distinct Mdm2, p53 and PML complexes and damage-specific nuclear relocalization". Journal of Cell Science. 116 (Pt 19): 3917–25. doi:10.1242/jcs.00714. PMID 12915590.

- ^ a b Freeman DJ, Li AG, Wei G, Li HH, Kertesz N, Lesche R, et al. (February 2003). "PTEN tumor suppressor regulates p53 protein levels and activity through phosphatase-dependent and -independent mechanisms". Cancer Cell. 3 (2): 117–30. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00021-7. PMID 12620407.

- ^ a b Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG (March 1998). "ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways". Cell. 92 (6): 725–34. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81401-4. PMID 9529249.

- ^ Badciong JC, Haas AL (December 2002). "MdmX is a RING finger ubiquitin ligase capable of synergistically enhancing Mdm2 ubiquitination". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (51): 49668–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M208593200. PMID 12393902.

- ^ Shvarts A, Bazuine M, Dekker P, Ramos YF, Steegenga WT, Merckx G, et al. (July 1997). "Isolation and identification of the human homolog of a new p53-binding protein, Mdmx" (PDF). Genomics. 43 (1): 34–42. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.4775. hdl:2066/142231. PMID 9226370. S2CID 11794685.

- ^ Frade R, Balbo M, Barel M (December 2000). "RB18A, whose gene is localized on chromosome 17q12-q21.1, regulates in vivo p53 transactivating activity". Cancer Research. 60 (23): 6585–9. PMID 11118038.

- ^ Drané P, Barel M, Balbo M, Frade R (December 1997). "Identification of RB18A, a 205 kDa new p53 regulatory protein which shares antigenic and functional properties with p53". Oncogene. 15 (25): 3013–24. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201492. PMID 9444950.

- ^ Hu MC, Qiu WR, Wang YP (November 1997). "JNK1, JNK2 and JNK3 are p53 N-terminal serine 34 kinases". Oncogene. 15 (19): 2277–87. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201401. PMID 9393873.

- ^ Lin Y, Khokhlatchev A, Figeys D, Avruch J (December 2002). "Death-associated protein 4 binds MST1 and augments MST1-induced apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (50): 47991–8001. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202630200. PMID 12384512.

- ^ Taniura H, Matsumoto K, Yoshikawa K (June 1999). "Physical and functional interactions of neuronal growth suppressor necdin with p53". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (23): 16242–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.23.16242. PMID 10347180.

- ^ Daniely Y, Dimitrova DD, Borowiec JA (August 2002). "Stress-dependent nucleolin mobilization mediated by p53-nucleolin complex formation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (16): 6014–22. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.16.6014-6022.2002. PMC 133981. PMID 12138209.

- ^ Colaluca IN, Tosoni D, Nuciforo P, Senic-Matuglia F, Galimberti V, Viale G, et al. (January 2008). "NUMB controls p53 tumour suppressor activity". Nature. 451 (7174): 76–80. Bibcode:2008Natur.451...76C. doi:10.1038/nature06412. PMID 18172499. S2CID 4431258.

- ^ a b c Choy MK, Movassagh M, Siggens L, Vujic A, Goddard M, Sánchez A, et al. (June 2010). "High-throughput sequencing identifies STAT3 as the DNA-associated factor for p53-NF-kappaB-complex-dependent gene expression in human heart failure". Genome Medicine. 2 (6) 37. doi:10.1186/gm158. PMC 2905097. PMID 20546595.

- ^ a b Zhang Y, Wolf GW, Bhat K, Jin A, Allio T, Burkhart WA, et al. (December 2003). "Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53-dependent ribosomal-stress checkpoint pathway". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (23): 8902–12. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.23.8902-8912.2003. PMC 262682. PMID 14612427.

- ^ Nikolaev AY, Li M, Puskas N, Qin J, Gu W (January 2003). "Parc: a cytoplasmic anchor for p53". Cell. 112 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01255-2. PMID 12526791.

- ^ Malanga M, Pleschke JM, Kleczkowska HE, Althaus FR (May 1998). "Poly(ADP-ribose) binds to specific domains of p53 and alters its DNA binding functions". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (19): 11839–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.19.11839. PMID 9565608.

- ^ Kahyo T, Nishida T, Yasuda H (September 2001). "Involvement of PIAS1 in the sumoylation of tumor suppressor p53". Molecular Cell. 8 (3): 713–8. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00349-5. PMID 11583632.

- ^ Wulf GM, Liou YC, Ryo A, Lee SW, Lu KP (December 2002). "Role of Pin1 in the regulation of p53 stability and p21 transactivation, and cell cycle checkpoints in response to DNA damage". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (50): 47976–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200538200. PMID 12388558.

- ^ Zacchi P, Gostissa M, Uchida T, Salvagno C, Avolio F, Volinia S, et al. (October 2002). "The prolyl isomerase Pin1 reveals a mechanism to control p53 functions after genotoxic insults". Nature. 419 (6909): 853–7. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..853Z. doi:10.1038/nature01120. PMID 12397362. S2CID 4311658.

- ^ Huang SM, Schönthal AH, Stallcup MR (April 2001). "Enhancement of p53-dependent gene activation by the transcriptional coactivator Zac1". Oncogene. 20 (17): 2134–43. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204298. PMID 11360197. S2CID 21331603.

- ^ Xie S, Wu H, Wang Q, Cogswell JP, Husain I, Conn C, et al. (November 2001). "Plk3 functionally links DNA damage to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis at least in part via the p53 pathway". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (46): 43305–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106050200. PMID 11551930.

- ^ Bahassi EM, Conn CW, Myer DL, Hennigan RF, McGowan CH, Sanchez Y, et al. (September 2002). "Mammalian Polo-like kinase 3 (Plk3) is a multifunctional protein involved in stress response pathways". Oncogene. 21 (43): 6633–40. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205850. PMID 12242661. S2CID 24106070.

- ^ Simons A, Melamed-Bessudo C, Wolkowicz R, Sperling J, Sperling R, Eisenbach L, et al. (January 1997). "PACT: cloning and characterization of a cellular p53 binding protein that interacts with Rb". Oncogene. 14 (2): 145–55. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1200825. PMID 9010216.

- ^ Fusaro G, Dasgupta P, Rastogi S, Joshi B, Chellappan S (November 2003). "Prohibitin induces the transcriptional activity of p53 and is exported from the nucleus upon apoptotic signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (48): 47853–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305171200. PMID 14500729.

- ^ Fogal V, Gostissa M, Sandy P, Zacchi P, Sternsdorf T, Jensen K, et al. (November 2000). "Regulation of p53 activity in nuclear bodies by a specific PML isoform". The EMBO Journal. 19 (22): 6185–95. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.22.6185. PMC 305840. PMID 11080164.

- ^ Guo A, Salomoni P, Luo J, Shih A, Zhong S, Gu W, et al. (October 2000). "The function of PML in p53-dependent apoptosis". Nature Cell Biology. 2 (10): 730–6. doi:10.1038/35036365. PMID 11025664. S2CID 13480833.

- ^ a b Zhang Z, Zhang R (March 2008). "Proteasome activator PA28 gamma regulates p53 by enhancing its MDM2-mediated degradation". The EMBO Journal. 27 (6): 852–64. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.25. PMC 2265109. PMID 18309296.

- ^ Lim ST, Chen XL, Lim Y, Hanson DA, Vo TT, Howerton K, et al. (January 2008). "Nuclear FAK promotes cell proliferation and survival through FERM-enhanced p53 degradation". Molecular Cell. 29 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.031. PMC 2234035. PMID 18206965.

- ^ Bernal JA, Luna R, Espina A, Lázaro I, Ramos-Morales F, Romero F, et al. (October 2002). "Human securin interacts with p53 and modulates p53-mediated transcriptional activity and apoptosis". Nature Genetics. 32 (2): 306–11. doi:10.1038/ng997. PMID 12355087. S2CID 1770399.

- ^ Stürzbecher HW, Donzelmann B, Henning W, Knippschild U, Buchhop S (April 1996). "p53 is linked directly to homologous recombination processes via RAD51/RecA protein interaction". The EMBO Journal. 15 (8): 1992–2002. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00550.x. PMC 450118. PMID 8617246.

- ^ Buchhop S, Gibson MK, Wang XW, Wagner P, Stürzbecher HW, Harris CC (October 1997). "Interaction of p53 with the human Rad51 protein". Nucleic Acids Research. 25 (19): 3868–74. doi:10.1093/nar/25.19.3868. PMC 146972. PMID 9380510.

- ^ Leng RP, Lin Y, Ma W, Wu H, Lemmers B, Chung S, et al. (March 2003). "Pirh2, a p53-induced ubiquitin-protein ligase, promotes p53 degradation". Cell. 112 (6): 779–91. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00193-4. PMID 12654245.

- ^ Sheng Y, Laister RC, Lemak A, Wu B, Tai E, Duan S, et al. (December 2008). "Molecular basis of Pirh2-mediated p53 ubiquitylation". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 15 (12): 1334–42. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1521. PMC 4075976. PMID 19043414.

- ^ Romanova LY, Willers H, Blagosklonny MV, Powell SN (December 2004). "The interaction of p53 with replication protein A mediates suppression of homologous recombination". Oncogene. 23 (56): 9025–33. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207982. PMID 15489903. S2CID 23482723.

- ^ Riva F, Zuco V, Vink AA, Supino R, Prosperi E (December 2001). "UV-induced DNA incision and proliferating cell nuclear antigen recruitment to repair sites occur independently of p53-replication protein A interaction in p53 wild type and mutant ovarian carcinoma cells". Carcinogenesis. 22 (12): 1971–8. doi:10.1093/carcin/22.12.1971. PMID 11751427.