Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hyperconjugation

View on WikipediaIn organic chemistry, hyperconjugation (σ-conjugation or no-bond resonance) refers to the delocalization of electrons with the participation of bonds of primarily σ-character. Usually, hyperconjugation involves the interaction of the electrons in a sigma (σ) orbital (e.g. C–H or C–C) with an adjacent unpopulated non-bonding p or antibonding σ* or π* orbitals to give a pair of extended molecular orbitals. However, sometimes, low-lying antibonding σ* orbitals may also interact with filled orbitals of lone pair character (n) in what is termed negative hyperconjugation.[1] Increased electron delocalization associated with hyperconjugation increases the stability of the system.[2][3] In particular, the new orbital with bonding character is stabilized, resulting in an overall stabilization of the molecule.[4] Only electrons in bonds that are in the β position can have this sort of direct stabilizing effect — donating from a sigma bond on an atom to an orbital in another atom directly attached to it. However, extended versions of hyperconjugation (such as double hyperconjugation[5]) can be important as well. The Baker–Nathan effect, sometimes used synonymously for hyperconjugation,[6] is a specific application of it to certain chemical reactions or types of structures.[7]

Applications

[edit]Hyperconjugation can be used to rationalize a variety of chemical phenomena, including the anomeric effect, the gauche effect, the rotational barrier of ethane, the beta-silicon effect, the vibrational frequency of exocyclic carbonyl groups, and the relative stability of substituted carbocations and substituted carbon centred radicals, and the thermodynamic Zaitsev's rule for alkene stability. More controversially, hyperconjugation is proposed by quantum mechanical modeling to be a better explanation for the preference of the staggered conformation rather than the old textbook notion of steric hindrance.[8][9]

Effect on chemical properties

[edit]Hyperconjugation affects several properties.[6][10]

- Bond length: Hyperconjugation is suggested as a key factor in shortening of sigma bonds (σ bonds). For example, the single C–C bonds in 1,3-butadiene and propyne are approximately 1.46 Å in length, much less than the value of around 1.54 Å found in saturated hydrocarbons. For butadiene, this can be explained as normal conjugation of the two alkenyl parts. But for propyne, it is generally accepted that this is due to hyperconjugation between the alkyl and alkynyl parts.

- Dipole moments: The large increase in dipole moment of 1,1,1-trichloroethane as compared with chloroform can be attributed to hyperconjugated structures.

- The heat of formation of molecules with hyperconjugation are greater than sum of their bond energies and the heats of hydrogenation per double bond are less than the heat of hydrogenation of ethylene.

- Stability of carbocations:

- (CH3)3C+ > (CH3)2CH+ > (CH3)CH2+ > CH3+

- The three C–H σ bonds of the methyl group(s) attached to the carbocation can undergo the stabilization interaction but only one of them can be aligned perfectly with the empty p-orbital, depending on the conformation of the carbon–carbon bond. Donation from the two misaligned C–H bonds is weaker.[11] The more adjacent methyl groups there are, the larger hyperconjugation stabilization is because of the increased number of adjacent C–H bonds.

Hyperconjugation in unsaturated compounds

[edit]Hyperconjugation was suggested as the reason for the increased stability of carbon-carbon double bonds as the degree of substitution increases. Early studies in hyperconjugation were performed by in the research group of George Kistiakowsky. Their work, first published in 1937, was intended as a preliminary progress report of thermochemical studies of energy changes during addition reactions of various unsaturated and cyclic compounds. The importance of hyperconjugation in accounting for this effect has received support from quantum chemical calculations.[12] The key interaction is believed to be the donation of electron density from the neighboring C–H σ bond into the π* antibonding orbital of the alkene (σC–H→π*). The effect is almost an order of magnitude weaker than the case of alkyl substitution on carbocations (σC–H→pC), since an unfilled p orbital is lower in energy, and, therefore, better energetically matched to a σ bond. When this effect manifests in the formation of the more substituted product in thermodynamically controlled E1 reactions, it is known as Zaitsev's rule, although in many cases the kinetic product also follows this rule. (See Hofmann's rule for cases where the kinetic product is the less substituted one.)

One set of experiments by Kistiakowsky involved collected heats of hydrogenation data during gas-phase reactions of a range of compounds that contained one alkene unit. When comparing a range of monoalkyl-substituted alkenes, they found any alkyl group noticeably increased the stability, but that the choice of different specific alkyl groups had little to no effect.[13]

A portion of Kistiakowsky's work involved a comparison of other unsaturated compounds in the form of CH2=CH(CH2)n-CH=CH2 (n=0,1,2). These experiments revealed an important result; when n=0, there is an effect of conjugation to the molecule where the ΔH value is lowered by 3.5 kcal. This is likened to the addition of two alkyl groups into ethylene. Kistiakowsky also investigated open chain systems, where the largest value of heat liberated was found to be during the addition to a molecule in the 1,4-position. Cyclic molecules proved to be the most problematic, as it was found that the strain of the molecule would have to be considered. The strain of five-membered rings increased with a decrease degree of unsaturation. This was a surprising result that was further investigated in later work with cyclic acid anhydrides and lactones. Cyclic molecules like benzene and its derivatives were also studied, as their behaviors were different from other unsaturated compounds.[13]

Despite the thoroughness of Kistiakowsky's work, it was not complete and needed further evidence to back up his findings. His work was a crucial first step to the beginnings of the ideas of hyperconjugation and conjugation effects.

Stabilization of 1,3-butadiyne and 1,3-butadiene

[edit]The conjugation of 1,3-butadiene was first evaluated by Kistiakowsky, a conjugative contribution of 3.5 kcal/mol was found based on the energetic comparison of hydrogenation between conjugated species and unconjugated analogues.[13] Rogers who used the method first applied by Kistiakowsky, reported that the conjugation stabilization of 1,3-butadiyne was zero, as the difference of ΔhydH between first and second hydrogenation was zero. The heats of hydrogenation (ΔhydH) were obtained by computational G3(MP2) quantum chemistry method.[14]

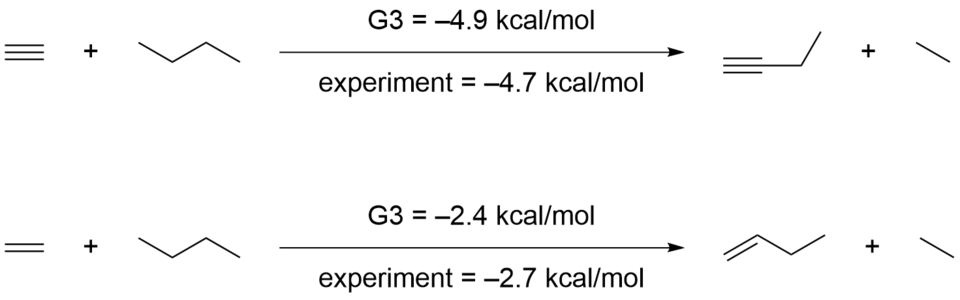

Another group led by Houk[15] suggested the methods employed by Rogers and Kistiakowsky was inappropriate, because that comparisons of heats of hydrogenation evaluate not only conjugation effects but also other structural and electronic differences. They obtained -70.6 kcal/mol and -70.4 kcal/mol for the first and second hydrogenation respectively by ab initio calculation, which confirmed Rogers’ data. However, they interpreted the data differently by taking into account the hyperconjugation stabilization. To quantify hyperconjugation effect, they designed the following isodesmic reactions in 1-butyne and 1-butene.

Deleting the hyperconjugative interactions gives virtual states that have energies that are 4.9 and 2.4 kcal/mol higher than those of 1-butyne and 1-butene, respectively. Employment of these virtual states results in a 9.6 kcal/mol conjugative stabilization for 1,3-butadiyne and 8.5 kcal/mol for 1,3-butadiene.

Trends in hyperconjugation

[edit]A relatively recent work by Fernández and Frenking (2006) summarized the trends in hyperconjugation among various groups of acyclic molecules, using energy decomposition analysis or EDA. Fernández and Frenking define this type of analysis as "...a method that uses only the pi orbitals of the interacting fragments in the geometry of the molecule for estimating pi interactions.[16]" For this type of analysis, the formation of bonds between various molecular moieties is a combination of three component terms. ΔEelstat represents what Fernández and Frenking call a molecule's “quasiclassical electrostatic attractions.[16]” The second term, ΔEPauli, represents the molecule's Pauli repulsion. ΔEorb, the third term, represents stabilizing interactions between orbitals, and is defined as the sum of ΔEpi and ΔEsigma. The total energy of interaction, ΔEint, is the result of the sum of the 3 terms.[16]

A group whose ΔEpi values were very thoroughly analyzed were a group of enones that varied in substituent.

Fernández and Frenking reported that the methyl, hydroxyl, and amino substituents resulted in a decrease in ΔEpi from the parent 2-propenal. Conversely, halide substituents of increasing atomic mass resulted in increasing ΔEpi. Because both the enone study and Hammett analysis study substituent effects (although in different species), Fernández and Frenking felt that comparing the two to investigate possible trends might yield significant insight into their own results. They observed a linear relationship between the ΔEpi values for the substituted enones and the corresponding Hammett constants. The slope of the graph was found to be -51.67, with a correlation coefficient of -0.97 and a standard deviation of 0.54.[16] Fernández and Frenking conclude from this data that ..."the electronic effects of the substituents R on pi conjugation in homo- and heteroconjugated systems is similar and thus appears to be rather independent of the nature of the conjugating system.".[16][17]

Rotational barrier of ethane

[edit]An instance where hyperconjugation may be overlooked as a possible chemical explanation is in rationalizing the rotational barrier of ethane (C2H6). It had been accepted as early as the 1930s that the staggered conformations of ethane were more stable than the eclipsed conformation. Wilson had proven that the energy barrier between any pair of eclipsed and staggered conformations is approximately 3 kcal/mol, and the generally accepted rationale for this was the unfavorable steric interactions between hydrogen atoms.

In their 2001 paper, however, Pophristic and Goodman[8] revealed that this explanation may be too simplistic.[18] Goodman focused on three principal physical factors: hyperconjugative interactions, exchange repulsion defined by the Pauli exclusion principle, and electrostatic interactions (Coulomb interactions). By comparing a traditional ethane molecule and a hypothetical ethane molecule with all exchange repulsions removed, potential curves were prepared by plotting torsional angle versus energy for each molecule. The analysis of the curves determined that the staggered conformation had no connection to the amount of electrostatic repulsions within the molecule. These results demonstrate that Coulombic forces do not explain the favored staggered conformations, despite the fact that central bond stretching decreases electrostatic interactions.[8]

Goodman also conducted studies to determine the contribution of vicinal (between two methyl groups) vs. geminal (between the atoms in a single methyl group) interactions to hyperconjugation. In separate experiments, the geminal and vicinal interactions were removed, and the most stable conformer for each interaction was deduced.[8]

| Deleted interaction | Torsional angle | Corresponding conformer |

|---|---|---|

| None | 60° | Staggered |

| All hyperconjugation | 0° | Eclipsed |

| Vicinal hyperconjugation | 0° | Eclipsed |

| Geminal hyperconjugation | 60° | Staggered |

From these experiments, it can be concluded that hyperconjugative effects delocalize charge and stabilize the molecule. Further, it is the vicinal hyperconjugative effects that keep the molecule in the staggered conformation.[8] Thanks to this work, the following model of the stabilization of the staggered conformation of ethane is now more accepted:

Hyperconjugation can also explain several other phenomena whose explanations may also not be as intuitive as that for the rotational barrier of ethane.[18]

The matter of the rotational barrier of ethane is not settled within the scientific community. An analysis within quantitative molecular orbital theory shows that 2-orbital-4-electron (steric) repulsions are dominant over hyperconjugation.[19] A valence bond theory study also emphasizes the importance of steric effects.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "hyperconjugation". doi:10.1351/goldbook.H02924

- ^ John McMurry. Organic chemistry, 2nd edition. ISBN 0-534-07968-7

- ^ Alabugin, I.V.; Gilmore, K.; Peterson, P. (2011). "Hyperconjugation". WIREs Comput Mol Sci. 1: 109–141. doi:10.1002/wcms.6. S2CID 222197582.

- ^ The mixed orbital of antibonding character is, in fact, raised in energy compared to the original antibonding orbital. However, since the antibonding orbital remains unpopulated in most cases, this does not usually affect the energy of the system.

- ^ Alabugin, I. V. (2016) Remote Stereoelectronic Effects, in Stereoelectronic Effects: A Bridge Between Structure and Reactivity, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK. doi:10.1002/9781118906378.ch8

- ^ a b Deasy, C.L. (1945). "Hyperconjugation". Chem. Rev. 36 (2): 145–155. doi:10.1021/cr60114a001.

- ^ Madan, R.L. (2013). "4.14: Hyperconjugation or No-bond Resonance". Organic Chemistry. Tata McGraw–Hill. ISBN 9789332901070.

- ^ a b c d e Pophristic, V.; Goodman, L. (2001). "Hyperconjugation not steric repulsion leads to the staggered structure of ethane". Nature. 411 (6837): 565–8. Bibcode:2001Natur.411..565P. doi:10.1038/35079036. PMID 11385566. S2CID 205017635.

- ^ Weinhold, Frank (2001). "Chemistry. A new twist on molecular shape". Nature. 411 (6837): 539–41. Bibcode:2001Natur.411..539W. doi:10.1038/35079225. PMID 11385553. S2CID 9812878.

- ^ Schmeising, H.N.; et al. (1959). "A Re-Evaluation of Conjugation and Hyperconjugation: The Effects of Changes in Hybridisation on Carbon Bonds". Tetrahedron. 5 (2–3): 166–178. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(59)80102-2.

- ^ Alabugin, Igor V.; Bresch, Stefan; dos Passos Gomes, Gabriel (2014). "Orbital hybridization: a key electronic factor in control of structure and reactivity". Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry. 28 (2): 147–162. doi:10.1002/poc.3382.

- ^ Braida, Benoit; Prana, Vinca; Hiberty, Philippe C. (2009). "The Physical Origin of Saytzeff's Rule". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48 (31): 5724–5728. doi:10.1002/anie.200901923. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 19562814.

- ^ a b c Kistiakowsky, G. B.; et al. (1937). "Energy Changes Involved in the Addition Reactions of Unsaturated Hydrocarbons". Chem. Rev. 20 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1021/cr60066a002.

- ^ Rogers, D. W.; et al. (2003). "The Conjugation Stabilization of 1,3-Butadiyne is Zero". Org. Lett. 5 (14): 2373–5. doi:10.1021/ol030019h. PMID 12841733.

- ^ Houk, K.N.; et al. (2004). "How Large is the Conjugative Stabilization of Diynes?". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (46): 15036–7. doi:10.1021/ja046432h. PMID 15547994.

- ^ a b c d e Fernandez, I.; Frenking, G. (2006). "Direct Estimate of the Strength of Conjugation and Hyperconjugation by the Energy Decomposition Analysis Method". Chem. Eur. J. 12 (13): 3617–29. doi:10.1002/chem.200501405. PMID 16502455.

- ^ Refer to Reference 12 for the graph and its full analysis

- ^ a b Schreiner, P. (2002). "Teaching the Right Reasons: Lessons from the Mistaken Origin of the Rotational Barrier in Ethane". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41 (19): 3579–81, 3513. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20021004)41:19<3579::AID-ANIE3579>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 12370897.

- ^ Bickelhaupt, F.M.; Baerends (2003). "The case for steric repulsion causing the staggered conformation of ethane". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42 (35): 4183–4188. doi:10.1002/anie.200350947. PMID 14502731.

- ^ Mo, Y.R.; et al. (2004). "The magnitude of hyperconjugation in ethane: A perspective from ab initio valence bond theory". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43 (15): 1986–1990. doi:10.1002/anie.200352931. PMID 15065281.