Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hydroxy group

View on Wikipedia

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula −OH and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy groups. Both the negatively charged anion HO−, called hydroxide, and the neutral radical HO·, known as the hydroxyl radical, consist of an unbonded hydroxy group.

According to IUPAC definitions, the term hydroxyl refers to the hydroxyl radical (·OH) only, while the functional group −OH is called a hydroxy group.[1]

Properties

[edit]

Water, alcohols, carboxylic acids, and many other hydroxy-containing compounds can be readily deprotonated due to a large difference between the electronegativity of oxygen (3.5) and that of hydrogen (2.1). Hydroxy-containing compounds engage in intermolecular hydrogen bonding increasing the electrostatic attraction between molecules and thus to higher boiling and melting points than found for compounds that lack this functional group. Organic compounds, which are often poorly soluble in water, become water-soluble when they contain two or more hydroxyl groups, as illustrated by sugars and amino acid.[2][3]

Occurrence

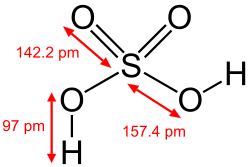

[edit]The hydroxy group is pervasive in chemistry and biochemistry. Many inorganic compounds contain hydroxyl groups, including sulfuric acid, the chemical compound produced on the largest scale industrially.[4]

Hydroxy groups participate in the dehydration reactions that link simple biological molecules into long chains. The joining of a fatty acid to glycerol to form a triacylglycerol removes the −OH from the carboxy end of the fatty acid. The joining of two aldehyde sugars to form a disaccharide removes the −OH from the carboxy group at the aldehyde end of one sugar. The creation of a peptide bond to link two amino acids to make a protein removes the −OH from the carboxy group of one amino acid.[citation needed]

Hydroxyl radical

[edit]Hydroxyl radicals are highly reactive and undergo chemical reactions that make them short-lived. When biological systems are exposed to hydroxyl radicals, they can cause damage to cells, including those in humans, where they can react with DNA, lipids, and proteins.[5]

Planetary observations

[edit]Airglow of the Earth

[edit]The Earth's night sky is illuminated by diffuse light, called airglow, that is produced by radiative transitions of atoms and molecules.[6] Among the most intense such features observed in the Earth's night sky is a group of infrared transitions at wavelengths between 700 nanometers and 900 nanometers. In 1950, Aden Meinel showed that these were transitions of the hydroxyl molecule, OH.[7]

Surface of the Moon

[edit]In 2009, India's Chandrayaan-1 satellite and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Cassini spacecraft and Deep Impact probe each detected evidence of water by evidence of hydroxyl fragments on the Moon. As reported by Richard Kerr, "A spectrometer [the Moon Mineralogy Mapper, also known as "M3"] detected an infrared absorption at a wavelength of 3.0 micrometers that only water or hydroxyl—a hydrogen and an oxygen bound together—could have created."[8] NASA also reported in 2009 that the LCROSS probe revealed an ultraviolet emission spectrum consistent with hydroxyl presence.[9]

On 26 October 2020, NASA reported definitive evidence of water on the sunlit surface of the Moon, in the vicinity of the crater Clavius (crater), obtained by the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).[10] The SOFIA Faint Object infrared Camera for the SOFIA Telescope (FORCAST) detected emission bands at a wavelength of 6.1 micrometers that are present in water but not in hydroxyl. The abundance of water on the Moon's surface was inferred to be equivalent to the contents of a 12-ounce bottle of water per cubic meter of lunar soil.[11]

The Chang'e 5 probe, which landed on the Moon on 1 December 2020, carried a mineralogical spectrometer that could measure infrared reflectance spectra of lunar rock and regolith. The reflectance spectrum of a rock sample at a wavelength of 2.85 micrometers indicated localized water/hydroxyl concentrations as high as 180 parts per million.[12]

Atmosphere of Venus

[edit]The Venus Express orbiter collected Venus science data from April 2006 until December 2014. In 2008, Piccioni, et al. reported measurements of night-side airglow emission in the atmosphere of Venus made with the Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS) on Venus Express. They attributed emission bands in wavelength ranges of 1.40–1.49 micrometers and 2.6–3.14 micrometers to vibrational transitions of OH.[13] This was the first evidence for OH in the atmosphere of any planet other than Earth.[13]

Atmosphere of Mars

[edit]In 2013, OH near-infrared spectra were observed in the night glow in the polar winter atmosphere of Mars by use of the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM).[14]

Exoplanets

[edit]In 2021, evidence for OH in the dayside atmosphere of the exoplanet WASP-33b was found in its emission spectrum at wavelengths between 1 and 2 micrometers.[15] Evidence for OH in the atmosphere of exoplanet WASP-76b was subsequently found.[16] Both WASP-33b and WASP-76b are ultra-hot Jupiters and it is likely that any water in their atmospheres is present as dissociated ions.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Alcohols". Gold Book. IUPAC. February 24, 2014. doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00204. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ "Khan Academy".

- ^ "6.3: Hydrogen Bonding Interactions and Solubility". 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Research Report 2012 – 2013" (PDF). Ludwig Maximilians Universität München Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on Dec 7, 2022.

- ^ Kanno, Taro; Nakamura, Keisuke; Ikai, Hiroyo; Kikuchi, Katsushi; Sasaki, Keiichi; Niwano, Yoshimi (July 2012). "Literature review of the role of hydroxyl radicals in chemically-induced mutagenicity and carcinogenicity for the risk assessment of a disinfection system utilizing photolysis of hydrogen peroxide". Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 51 (1): 9–14. doi:10.3164/jcbn.11-105. ISSN 0912-0009. PMC 3391867. PMID 22798706.

- ^ Silverman SM (October 1970). "Night airglow phenomenology". Space Science Reviews. 11 (2): 341–79. Bibcode:1970SSRv...11..341S. doi:10.1007/BF00241526. S2CID 120677542. Archived from the original on Oct 5, 2023.

- ^ Meinel AB (1950). "OH Emission Bands in the Spectrum of the Night Sky. I". Astrophysical Journal. 111: 555–564. Bibcode:1950ApJ...111..555M. doi:10.1086/145296. Archived from the original on Oct 24, 2022.

- ^ Kerr RA (24 September 2009). "A Whiff of Water Found on the Moon". Science. Archived from the original on Dec 8, 2023. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

- ^ Dino J (13 November 2009). "LCROSS Impact Data Indicates Water on Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 2009-11-15. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ^ Honniball CI, Lucey PG, Li S, Shenoy S, Orlando TM, Hibbitts CA, Hurley DM, Farrell WM (2020). "Molecular water detected on the sunlit Moon by SOFIA". Nature Astronomy. 5 (2): 121–127. Bibcode:2021NatAs...5..121H. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-01222-x. S2CID 228954129.

- ^ Chou F, Hawkes A (26 October 2020). "NASA's SOFIA Discovers Water on Sunlit Surface of Moon". NASA. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ Lin H, Li S, Xu R, Liu Y, Wu X, Yang W, Wei Y, Lin Y, He Z, Hui H, He K, Hu S, Zhang C, Li C, Lv G, Yuan L, Zou Y, Wang C (2022). "In situ detection of water on the Moon by the Chang'E-5 lander". Science Advances. 8 (1) eabl9174. Bibcode:2022SciA....8.9174L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abl9174. PMC 8741181. PMID 34995111.

- ^ a b Piccioni, G.; Drossart, P.; Zasova, L.; Migliorini, A.; Gérard, J.-C.; Mills, F. P.; Shakun, A.; García Muñoz, A.; Ignatiev, N.; Grassi, D.; Cottini, V.; Taylor, F. W.; Erard, S. (2008-04-01). "First detection of hydroxyl in the atmosphere of Venus". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 483 (3). EDP Sciences: L29 – L33. Bibcode:2008A&A...483L..29P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809761. hdl:1885/35639. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Clancy RT, Sandor BJ, García-Muñoz A, Lefèvre F, Smith MD, Wolff MJ, Montmessin F, Murchie SL, Nair H (2013). "First detection of Mars atmospheric hydroxyl: CRISM Near-IR measurement versus LMD GCM simulation of OH Meinel band emission in the Mars polar winter atmosphere". Icarus. 226 (1): 272–281. Bibcode:2013Icar..226..272T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.05.035.

- ^ Stevanus K. Nugroho; Hajime Kawahara; Neale P. Gibson; Ernst J. W. de Mooij; Teruyuki Hirano; Takayuki Kotani; Yui Kawashima; Kento Masuda; Matteo Brogi; Jayne L. Birkby; Chris A. Watson; Motohide Tamura; Konstanze Zwintz; Hiroki Harakawa; Tomoyuki Kudo; Masayuki Kuzuhara; Klaus Hodapp; Masato Ishizuka; Shane Jacobson; Mihoko Konishi; Takashi Kurokawa; Jun Nishikawa; Masashi Omiya; Takuma Serizawa; Akitoshi Ueda; Sébastien Vievard (2021). "First Detection of Hydroxyl Radical Emission from an Exoplanet Atmosphere: High-dispersion Characterization of {WASP}-33b Using Subaru/{IRD}" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal Letters. 910 (1): L9. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abec71. S2CID 232110452.

- ^ R. Landman; A. Sánchez-López; P. Mollière; A. Y. Kesseli; A. J. Louca; I. A. G. Snellen (2021). "Detection of OH in the ultra-hot Jupiter WASP-76b". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 656 (1): A119. arXiv:2110.11946. Bibcode:2021A&A...656A.119L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202141696. S2CID 239616465.

Further

[edit]- Reece J, Urry L, Cain M, Wasserman S, Minorsky P, Jackson R (2011). "Chapter 4&5". In Berge S, Golden B, Triglia L (eds.). Campbell Biology. Vol. Unit 1 (9th ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-321-55823-7.