Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Interaction nets

View on WikipediaInteraction nets are a graphical model of computation devised by French mathematician Yves Lafont in 1990[1] as a generalisation of the proof structures of linear logic. An interaction net system is specified by a set of agent types and a set of interaction rules. Interaction nets are an inherently distributed model of computation in the sense that computations can take place simultaneously in many parts of an interaction net, and no synchronisation is needed. The latter is guaranteed by the strong confluence property of reduction in this model of computation. Thus interaction nets provide a natural language for massive parallelism. Interaction nets are at the heart of many implementations of the lambda calculus, such as efficient closed reduction[2] and optimal, in Lévy's sense, Lambdascope.[3]

Definitions

[edit]Interactions nets are graph-like structures consisting of agents and edges.

An agent of type and with arity has one principal port and auxiliary ports. Any port can be connected to at most one edge. Any edge is connected to exactly two ports. Ports that are not connected to any edge are called free ports. Free ports together form the interface of an interaction net. All agent types belong to a set called signature.

An interaction net that consists solely of edges is called a wiring and usually denoted as . A tree with its root is inductively defined either as an edge , or as an agent with its free principal port and its auxiliary ports connected to the roots of other trees .

Graphically, the primitive structures of interaction nets can be represented as follows:

When two agents are connected to each other with their principal ports, they form an active pair. For active pairs one can introduce interaction rules which describe how the active pair rewrites to another interaction net. An interaction net with no active pairs is said to be in normal form. A signature (with defined on it) along with a set of interaction rules defined for agents together constitute an interaction system.

Interaction calculus

[edit]Textual representation of interaction nets is called the interaction calculus[4] and can be seen as a programming language.

Inductively defined trees correspond to terms in the interaction calculus, where is called a name.

Any interaction net can be redrawn using the previously defined wiring and tree primitives as follows:

which in the interaction calculus corresponds to a configuration

,

where , , and are arbitrary terms. The ordered sequence in the left-hand side is called an interface, while the right-hand side contains an unordered multiset of equations . Wiring translates to names, and each name has to occur exactly twice in a configuration.

Just like in the -calculus, the interaction calculus has the notions of -conversion and substitution naturally defined on configurations. Specifically, both occurrences of any name can be replaced with a new name if the latter does not occur in a given configuration. Configurations are considered equivalent up to -conversion. In turn, substitution is the result of replacing the name in a term with another term if has exactly one occurrence in the term .

Any interaction rule can be graphically represented as follows:

where , and the interaction net on the right-hand side is redrawn using the wiring and tree primitives in order to translate into the interaction calculus as using Lafont's notation.

The interaction calculus defines reduction on configurations in more details than seen from graph rewriting defined on interaction nets. Namely, if , the following reduction:

is called interaction. When one of equations has the form of , indirection can be applied resulting in substitution of the other occurrence of the name in some term :

or .

An equation is called a deadlock if has occurrence in term . Generally only deadlock-free interaction nets are considered. Together, interaction and indirection define the reduction relation on configurations. The fact that configuration reduces to its normal form with no equations left is denoted as .

Properties

[edit]Interaction nets benefit from the following properties:

- locality (only active pairs can be rewritten);

- linearity (each interaction rule can be applied in constant time);

- strong confluence also known as one-step diamond property (if and , then and for some ).

These properties together allow massive parallelism.

Interaction combinators

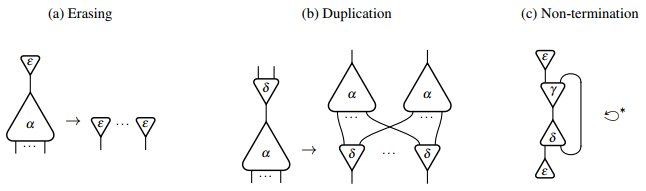

[edit]One of the simplest interaction systems that can simulate any other interaction system is that of interaction combinators.[5] Its signature is with and . Interaction rules for these agents are:

- called erasing;

- called duplication;

- and called annihilation.

Graphically, the erasing and duplication rules can be represented as follows:

with an example of a non-terminating interaction net that reduces to itself. Its infinite reduction sequence starting from the corresponding configuration in the interaction calculus is as follows:

Non-deterministic extension

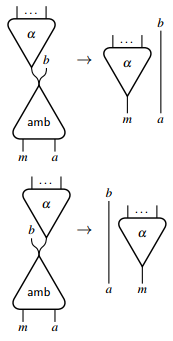

[edit]Interaction nets are essentially deterministic and cannot model non-deterministic computations directly. In order to express non-deterministic choice, interaction nets need to be extended. In fact, it is sufficient to introduce just one agent [6] with two principal ports and the following interaction rules:

This distinguished agent represents ambiguous choice and can be used to simulate any other agent with arbitrary number of principal ports. For instance, it allows to define a boolean operation that returns true if any of its arguments is true, independently of the computation taking place in the other arguments.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lafont, Yves (1990). "Interaction nets". Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT symposium on Principles of programming languages - POPL '90. ACM. pp. 95–108. doi:10.1145/96709.96718. ISBN 0897913434. S2CID 1165803.

- ^ Mackie, Ian (2008). "An Interaction Net Implementation of Closed Reduction". Implementation and Application of Functional Languages: 20th International Symposium. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5836. pp. 43–59. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-24452-0_3. ISBN 978-3-642-24451-3.

- ^ van Oostrom, Vincent; van de Looij, Kees-Jan; Zwitserlood, Marijn (2010). "Lambdascope: Another optimal implementation of the lambda-calculus" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fernández, Maribel; Mackie, Ian (1999). "A calculus for interaction nets". Principles and Practice of Declarative Programming. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 1702. Springer. pp. 170–187. doi:10.1007/10704567. ISBN 978-3-540-66540-3. S2CID 19458687.

- ^ Lafont, Yves (1997). "Interaction Combinators". Information and Computation. 137 (1). Academic Press, Inc.: 69–101. doi:10.1006/inco.1997.2643.

- ^ Fernández, Maribel; Khalil, Lionel (2003). "Interaction Nets with McCarthy's Amb: Properties and Applications". Nordic Journal of Computing. 10 (2): 134–162.

Further reading

[edit]- Asperti, Andrea; Guerrini, Stefano (1998). The Optimal Implementation of Functional Programming Languages. Cambridge Tracts in Theoretical Computer Science. Vol. 45. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521621120.

- Fernández, Maribel (2009). "Interaction-Based Models of Computation". Models of Computation: An Introduction to Computability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 107–130. ISBN 9781848824348.

External links

[edit]- de Falco, Marc. "tikz-inet. A set of tikz-based macros for drawing interaction nets".

- de Falco, Marc. "INL. Interaction Nets Laboratory".

- Vilaça, Miguel. "INblobs. An editor and interpreter for Interaction Nets".

- Asperti, Andrea. "The Bologna Optimal Higher-Order Machine". GitHub.

- Salikhmetov, Anton (22 March 2018). "JavaScript Engine for Interaction Nets".

- Salikhmetov, Anton. "Macro Lambda Calculus".

- Xie, Yuheng. "iNet, a language and interactive playground for exploring interaction nets".

Interaction nets

View on GrokipediaHistory and Motivation

Origins

Interaction nets were introduced by French mathematician Yves Lafont in 1990 as a graphical model of computation designed to capture parallel reduction strategies efficiently.[1] This foundational work generalized the proof structures known as proof nets from linear logic into a broader framework for computation.[4] The development of interaction nets was motivated by advances in proof theory and categorical logic during the late 1980s, particularly the need for a graphical representation that avoided the inefficiencies of traditional term rewriting systems while enabling local, atomic interactions. Lafont's seminal paper, "Interaction Nets," presented at the 17th ACM Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages (POPL '90), established the core principles, emphasizing determinism and strong confluence to model computational processes akin to those in functional programming.[1] Key milestones followed rapidly. In 1995, Lafont published "From Proof-Nets to Interaction Nets" in Advances in Linear Logic, bridging the gap between logical proofs and computational graphs more formally.[4] By 1997, his paper "Interaction Combinators" extended the model to a Turing-complete system using a minimal set of combinators, incorporating mechanisms for sharing and garbage collection that supported optimal reduction strategies in lambda calculus implementations. These developments up to 1997 solidified interaction nets as a foundation for efficient parallel computing paradigms. Post-1990, researchers like Ian Mackie advanced practical implementations, notably with YALE (Yet Another Lambda Evaluator) in 1998, an efficient interaction net-based evaluator for the lambda calculus that addressed encoding inefficiencies.[5] Similarly, Vincent van Oostrom contributed to optimal reduction techniques, co-developing Lambdascope around 2004 as another high-performance lambda calculus implementation using interaction nets for Lévy-optimal reductions.[6] These efforts highlighted the model's applicability to real-world functional programming evaluators.Relation to Linear Logic

Interaction nets were developed as a graphical model of computation that generalizes the proof nets of linear logic, providing a framework for resource-sensitive parallel reductions beyond logical proofs. Linear logic, introduced by Jean-Yves Girard in 1987, refines classical logic by treating formulas as consumable resources, thereby restricting structural rules like contraction and weakening to better model computational scarcity and multiplicity.[7] Within linear logic, proof nets represent sequent calculus proofs as graphs whose reductions correspond to cut-elimination, offering a parallel and confluent alternative to sequential proof normalization.[7] In his 1990 paper, Yves Lafont proposed interaction nets as a broader generalization of these proof nets, extending their principles to arbitrary computational systems while preserving key properties like determinism and local interactions. This framework shifts the focus from static proof verification to dynamic, distributed computation, where nets evolve through rewriting rules that enforce resource management akin to linear logic's tensorial and exponential modalities. Central to this relation are structural parallels: atomic agents in interaction nets correspond to axiom links in proof nets, both acting as foundational nodes that link principal ports to represent basic assertions or data elements without duplication. Interactions between agents, triggered only when two active ports connect, mimic cut-elimination steps in linear logic, reducing the net in a way that eliminates "cuts" or conflicts while propagating connections locally. A key advantage of interaction nets over traditional proof nets is their applicability to non-logical computations, such as encoding Turing machines or simulating strong normalization in typed lambda calculi, which proof nets—limited to linear-time reductions in the logical setting—cannot efficiently handle. This extension supports resource-aware programming paradigms, including functional languages, by allowing nets to model higher-order functions and recursion without the rigidity of proof structures. As a concrete illustration, the multiplicative fragment of linear logic—which includes the tensor (multiplicative conjunction) and par (multiplicative disjunction) connectives—maps directly to interaction nets, where agents embody these operators and their interactions enforce the fragment's inference rules through graph rewrites that preserve logical equivalence. Lafont's 1990 work briefly outlines this mapping as a foundational step in bridging logical proofs with general-purpose computing.Formal Definition

Agents and Nets

Interaction nets consist of agents connected by wires in a graphical structure that models computation through local rewrites. An agent is a typed atomic symbol drawn from a finite signature , characterized by an arity , featuring exactly one principal port and auxiliary ports. The principal port serves as the primary interaction point, while auxiliary ports enable connections to other agents or the external interface. A net is a finite undirected multigraph in which nodes represent agents and edges, termed wires, connect compatible ports between agents or to the exterior. Free ports—those not connected to another port within the net—collectively form the interface, allowing nets to be composed or linked to other nets. The signature comprises a finite set of distinct agent types, each assigned a specific arity that dictates the number of its auxiliary ports. An active pair arises when the principal ports of exactly two agents are directly connected by a single wire, positioning the net for a local rewrite operation. As an illustrative example, a basic net might feature two agents and linked solely by a wire between their principal ports, with all auxiliary ports left free; these free ports then constitute the net's interface for further connections. A net reaches its normal form when it possesses no active pairs, rendering it irreducible under the system's rules.Interaction Rules

Interaction nets are governed by an interaction system defined as a pair , where is a finite set of agent symbols and is a finite set of interaction rules that specify the allowed rewrites between agents.[8] Each rule in describes a binary interaction between two distinct agent types and , denoted as , where the principal ports of and are directly connected to form an active pair. The left side of the rule depicts the connected and agents, while the right side shows the replacement net that substitutes this pair, with all auxiliary port connections from the original agents preserved and reconnected to the new agents. This replacement ensures that the overall net structure remains intact except at the local interaction site.[8] A generic binary interaction rule takes the form , where and are the principal ports of and , respectively, and (for ) and (for ) are the auxiliary ports. In this notation, the variables representing the wires connected to auxiliary ports occur exactly once on the left side and once on the right side, maintaining the connectivity of the net during reduction.[8] Interaction rules adhere to three key constraints to ensure well-behaved computation. First, linearity requires that each auxiliary port variable appears exactly once on each side of the rule, preventing duplication or loss of connections. Second, locality confines the rewrite to the active pair alone, without affecting distant parts of the net. Third, determinism mandates that there is at most one rule for each unordered pair of distinct symbols , with no rules defined for a symbol interacting with itself, guaranteeing a unique rewrite for any active pair.[8]Computational Model

Interaction Calculus

The interaction calculus provides a textual syntax for representing interaction nets, allowing formal manipulation and analysis of their computational behavior as a programming language-like formalism. This calculus encodes the graphical structure of nets using terms and configurations, facilitating algebraic operations while preserving the essential properties of interactions between agents. It was developed to bridge the graphical model introduced by Lafont with more traditional term-rewriting frameworks, enabling proofs and implementations in a linear, confluent manner. Terms in the interaction calculus are defined by the grammar , where is a variable representing a free port, and is an agent type (or symbol) with arity , connected to subterms at its auxiliary ports. The principal port of is implicitly free unless bound in a larger structure. This syntax mirrors the node-and-edge structure of graphical agents, where each agent has one distinguished principal port for interactions and multiple auxiliary ports for connections. Configurations extend terms to represent entire nets as multi-hole contexts with bindings: . Here, the are terms occupying holes (free principal ports), and the equations denote wirings between variables, capturing connections between auxiliary ports across the net. This form allows the representation of disconnected components and shared bindings, akin to multi-contexts in process calculi, while ensuring linearity by restricting variables to exactly two occurrences. Alpha-conversion in the interaction calculus involves renaming bound variables in configurations to avoid capture, analogous to the process in lambda calculus. Specifically, a variable bound in an equation can be consistently renamed throughout the configuration without altering its meaning, preserving the net's topology and interaction potential. This operation ensures fresh names during manipulations, maintaining acyclicity and well-formedness. Substitution is defined as , which replaces all free occurrences of variable in term with term , while preserving the free ports and respecting the linearity constraint that no variable appears more than twice. This operation is crucial for propagating connections after interactions, and it is performed modulo alpha-conversion to handle bindings correctly. Substitutions in configurations update multiple terms simultaneously via the binding equations. The indirection rule eliminates variables in configurations by converting a substitution-like binding: if a configuration contains , it reduces to one where is replaced by throughout, effectively inlining the term to simplify the net. Formally, (modulo other bindings), removing the indirection and potentially exposing new active pairs. This rule supports garbage collection and optimization in reductions. As an example, consider a simple binary interaction between two agents and in textual form: . Here, the principal ports of and are free (the holes), connected via the binding at auxiliary ports, representing an active pair ready for reduction. Applying alpha-conversion if needed (e.g., renaming to ) and substitution would prepare this for an interaction rule, while the indirection rule could inline if for some term . This configuration illustrates how textual forms capture graphical active pairs without explicit diagrams. A notable modern development building on the general concept of interaction calculus is the specific Interaction Calculus introduced by Victor Taelin and the HigherOrderCO group. This is a minimal term rewriting system inspired by the lambda calculus but grounded in interaction nets principles, providing a textual syntax for representing interaction combinators. It forms the basis for practical implementations, such as the HVM runtime, which enables massively parallel evaluation of functional programs encoded in interaction nets.[9][10]Reduction Semantics

The reduction semantics of interaction nets operates on configurations, which represent nets possibly augmented with bindings for free ports, via a one-step reduction relation denoted . This relation encompasses two complementary mechanisms: interaction reduction, which applies rewriting rules to active pairs, and indirection reduction, which simplifies variable bindings. These steps collectively drive the computation toward a normal form, where no further reductions are possible.[8][11] Interaction reduction targets an active pair, consisting of two agents and connected via their principal ports (), replacing the pair with the right-hand side net specified by the interaction rule for that symbol combination. Rules are constrained to ensure linearity (each auxiliary port appears exactly twice across left and right sides), binarity (left side is precisely the active pair), unambiguity (at most one rule per distinct agent pair), and optimization (right side contains no active pairs). For instance, in a net encoding list operations, the rule for concatenating difference lists might rewrite to , reconnecting auxiliary ports accordingly and preserving the overall net structure. This local rewrite is atomic and does not alter distant parts of the configuration.[8] Indirection reduction addresses bindings of the form , where is a free port (variable) connected to a term , by eliminating the indirection and substituting the connection directly. In implementations using auxiliary indirection nodes (e.g., denoted as \t )), this involves rules such as ( $t = s \to t = s t = $s \to t = s $, which propagate the binding and simplify the configuration by removing the node. This step is essential for resolving deferred connections introduced during prior interactions, ensuring the net remains compact without unnecessary intermediaries. Together with interaction steps, indirections enable the full reduction relation to handle both computational rewriting and structural simplification.[11] A configuration reaches normal form when it contains no active pairs and all bindings are resolved, meaning no further -steps apply. Deadlock-freeness holds for simple configurations—those free of vicious circles (cycles through principal ports)—guaranteeing termination in a normal form without infinite reduction or stalled active pairs. This property arises from the rule constraints and net construction principles, preventing pathological loops.[8][2] Parallel reduction extends the semantics by allowing simultaneous application of non-interfering steps to multiple disjoint active pairs (or indirections) within a single -step, leveraging the locality of rules. Strong confluence ensures that any sequence of such parallel or sequential reductions yields the same normal form, independent of the order or degree of parallelism chosen.[8][2] As an illustrative example, consider a simple configuration in interaction combinators with an active pair of two -agents connected at principal ports, alongside free ports. The interaction rule (with auxiliary ports crossed) replaces the pair in one step, yielding two -agents connected via auxiliaries, which forms a normal form since has no principal port and no active pairs remain. If indirections were present (e.g., a free port bound to \ \epsilon + \ [ \mathrm{Parse}(u, \mathrm{Parse}(w, y)) ] + \mathrm{Parse}\mathrm{Parse}( \mathrm{Plus}(v, w), y )$, a normal form ready for output observation.[8]Key Properties

Confluence and Parallelism

Interaction nets exhibit a strong confluence property, ensuring that the order of reductions does not affect the final result. Formally, if a net reduces in one step to nets and via distinct active pairs, then there exists a net such that reduces in one step to and reduces in one step to . This one-step diamond property extends to multi-step reductions, implying the Church-Rosser theorem: for any sequences of reductions from a common net to and , there exists a net such that reduces to and reduces to . The proof of strong confluence relies on two key design principles of interaction nets: locality and determinism. Locality ensures that each reduction step replaces only the connected active pair of agents, without affecting disjoint parts of the net, as rewrites occur within isolated contexts defined by the wiring. Determinism guarantees that for any pair of agent symbols, at most one interaction rule exists, preventing ambiguous or overlapping reductions that could lead to divergence. When two redexes are disjoint, their reductions commute directly due to locality; if they share structure, the unique rule per principal port pair ensures a common successor without interference. This confluence enables efficient parallelism in interaction net computation. Since reductions of disjoint active pairs are independent and converge to the same normal form regardless of order, no global synchronization is required between parallel steps, allowing reductions to proceed concurrently without coordination overhead. Consequently, interaction nets support distributed implementations where local interactions can be evaluated in parallel across separate processors, mirroring the inherent locality of the model. In comparison to the lambda calculus, where beta-reduction satisfies confluence via the Church-Rosser theorem but lacks strong confluence without a specific evaluation strategy (potentially leading to non-local effects), interaction net reductions achieve strong confluence inherently through their graphical structure and rule constraints. For example, consider a net containing two disjoint active pairs; reducing one pair followed by the other yields the same normal form as reducing both in parallel, demonstrating how the property preserves correctness under concurrent execution.Efficiency Characteristics

Interaction nets exhibit notable efficiency characteristics stemming from their design principles, particularly in how reductions are performed. A key feature is the locality of rewrites, where each interaction involves only an active pair of agents connected via their principal ports, along with any directly connected auxiliary agents, without requiring any global search across the net. This localized operation ensures that reductions are confined to a small, fixed portion of the graph, minimizing computational overhead and enabling straightforward parallel execution where multiple disjoint active pairs exist.[12] The linearity condition of interaction nets further enhances efficiency by stipulating that each auxiliary port connects to at most one other port, meaning every edge in the net appears exactly twice—once at each endpoint. Consequently, each rule application operates in constant time, O(1), independent of the overall net size, as the rewiring process involves a fixed number of pointer updates to replace the interacting agents with the right-hand side net while preserving free ports.[12] This linearity also bounds resource usage strictly by the net's size, eliminating the need for garbage collection since no dangling references or unused structures accumulate during computation. Interaction nets support optimal implementations in encodings of higher-level languages, such as lambda calculus, by facilitating closed reduction strategies that avoid redundant computations through inherent sharing mechanisms.[13] For instance, in a binary interaction rule application like the addition of successor agents in an arithmetic encoding—whereAdd(S(x), y) interacts with a successor to yield S(Add(x, y))—the rewrite completes in constant time by locally substituting the agents and reconnecting the involved ports, demonstrating how the entire process scales independently of the represented values.[3]

Specific Systems

Interaction Combinators

Interaction combinators form a minimal universal subsystem of interaction nets, consisting of just three agent types: the eraser ε of arity 0, the duplicator δ of arity 2, and the mediator γ of arity 2. The eraser ε serves to terminate connections, possessing a single principal port with no auxiliary ports. The duplicator δ copies information across its two auxiliary ports when interacting appropriately, while the mediator γ facilitates connections between its two auxiliary ports in a structured manner, enabling the construction of complex nets. These agents connect via wires at their ports, with interactions occurring only when two principal ports are linked, following strict locality and determinism principles.[14] The system is governed by six interaction rules, each specifying a local rewrite when two agents are connected at their principal ports. The ε-ε rule annihilates the pair, reducing to an empty net: The δ-ε rule erases the duplicator: if δ with auxiliary ports connected to terms x and y is principally linked to ε, denoted δ(x, y) — ε, it reduces to x — ε y — ε, connecting each auxiliary port to a new ε agent. The γ-ε rule erases the mediator: γ(x, y) — ε → x — y, directly connecting the two auxiliary ports. The δ-γ rule mediates the interaction by restructuring connections: δ(x, y) — γ(u, v) → γ(δ(x, u), δ(y, v)), producing a single γ whose auxiliary ports connect to the principal ports of two δ agents, with the δ agents' auxiliary ports wired to x with u and y with v, respectively. The γ-γ rule similarly restructures without crossing: γ(x, y) — γ(u, v) → δ(γ(x, u), γ(y, v)), yielding a δ whose auxiliary ports connect to the principal ports of two γ agents, with the γ agents' auxiliary ports connected as x to u and y to v. The δ-δ rule restructures with crossing: δ(x, y) — δ(u, v) → γ(δ(x, v), δ(y, u)), yielding a γ whose auxiliary ports connect to the principal ports of two δ agents, with crossed wiring: x to v and y to u. This minimal set of rules renders interaction combinators Turing-complete and universal for interaction nets, as any general interaction net can be encoded using these agents via a translation that simulates arbitrary agents with menus and selectors built from γ and δ. In particular, lambda calculus terms can be encoded, with abstractions represented as γ-nets that mediate variable binding and application through auxiliary port connections. For instance, a lambda abstraction λx.M translates to a γ agent whose auxiliary ports link to the encoding of x and M, facilitating β-reduction via γ interactions.[14] An example of a non-terminating net, analogous to the Ω term in lambda calculus, involves a cyclic configuration of δ and γ agents that loops indefinitely. Specifically, a net with a γ connected principally to a δ, where the δ's auxiliary ports link back directly to the γ's auxiliary ports, reduces in four steps to an isomorphic copy of itself, perpetuating the cycle without normalization.[14]Non-Deterministic Extensions

Non-deterministic extensions to interaction nets address limitations in modeling computations involving choice or ambiguity, which standard deterministic nets cannot capture due to their strict one-to-one interaction rules. A prominent such extension introduces the amb agent, inspired by McCarthy's nondeterministic amb operator from Lisp, to enable selective reduction paths. This agent allows interaction nets to simulate non-deterministic behaviors, such as those found in concurrent systems or parallel algorithms requiring branching decisions.[15] The amb agent is defined with an arity of 2 and two principal ports, which serve as inputs for connecting two sub-nets between which a choice must be made. Its auxiliary ports (two in total) interface with the rest of the net. The interaction rule for amb, when connected to agents α and β on its principal ports, permits non-deterministic reduction: the net evolves either to a configuration where α connects to amb's main output while β's auxiliary ports remain attached, or symmetrically to the configuration where β connects to the output and α's ports are preserved. This rule selection occurs arbitrarily, introducing genuine nondeterminism into the reduction process.[15] A direct consequence of incorporating the amb agent is the loss of strong confluence, a hallmark property of vanilla interaction nets that guarantees unique normal forms regardless of reduction order. With amb, parallel reductions can yield multiple distinct normal forms, reflecting the inherent ambiguity of nondeterministic choices and enabling the representation of computations with multiple possible outcomes.[15] An illustrative example is the implementation of parallel-or (por) for boolean logic, which cannot be encoded in deterministic interaction nets due to its need for superposition-like rules. The por operation reduces to true if at least one input is true (por(true, x) → true or por(x, true) → true) and to false only if both inputs are false (por(false, false) → false). By integrating amb, the net for amb(true, false) nondeterministically selects the true branch, aligning with the semantics of parallel-or and demonstrating how amb handles such choice-based logic.[15] These extensions find applications in modeling concurrency, where the amb agent simulates fair or angelic nondeterministic choice in parallel processes, facilitating encodings of process calculi like the π-calculus and non-sequential functions such as merges in term rewriting systems. This capability extends interaction nets' utility beyond deterministic parallel computation to broader domains involving ambiguity and interaction in distributed settings.[15]Applications and Implementations

Encoding Functional Languages

Interaction nets offer a graphical rewriting model for encoding functional languages like the lambda calculus, facilitating efficient evaluation through local interactions that preserve sharing and support parallelism. In this encoding, lambda terms are translated into nets where variables are represented as free ports on the net's interface, allowing them to connect to multiple occurrences without explicit duplication until needed. Abstractions are encoded using γ-nets, which manage binding by duplicating subterms upon application, while applications are represented by δ-nets that connect the function and argument ports to enable beta-reduction via active pairs.[16][17] The closed reduction strategy in this framework focuses on reducing redexes (reducible expressions) internally without performing eta-expansions, which avoids unnecessary term growth and ensures efficient normalization for closed terms. This strategy leverages explicit substitutions to handle variable bindings, reducing the net by interacting agents at active pairs while maintaining the interface unchanged.[13] A notable implementation is Lambdascope, developed by van Oostrom, van de Looij, and Zwitserlood in 2004, which serves as an optimal reducer for the lambda calculus based on interaction nets, achieving full laziness and sharing without garbage collection overhead. The encoding requires O(n) space for lambda terms of size n, as the graph structure directly mirrors the term's syntax tree with shared substructures, and it inherently supports parallel evaluation since interactions occur locally and independently across the net.[18][19] As an example, the S and K combinators—foundational for encoding lambda terms without variables—can be represented in interaction combinators as specific net configurations. The K combinator, which discards its second argument, is encoded as a net with a Z₃ cell connected to a D cell and an ε cell: K = Z₃ D ε. The S combinator, which applies its first argument to the third twice with the second applied to the third, uses δ, Z₄, ζ, and D cells: S = δ Z₄ Z₄ Z₄ ζ ζ ζ D. These encodings reduce via the standard interaction rules, demonstrating how combinatory logic translates to efficient net reductions.[20]Visual and Concurrent Programming

Interaction nets have been employed in visual programming environments where the graphical structure of the nets serves as a direct, manipulable representation of computational processes. This approach allows programmers to interact with diagrams visually, providing intuitive insights into algorithm dynamics and facilitating error detection through graphical inspection. For instance, nets can be edited by connecting agents and ports, enabling a form of direct manipulation that mirrors the underlying graph rewriting mechanics.[21] In practical implementations, interaction nets support the development of compilers and abstract machines tailored for net-based languages. The Interaction Abstract Machine (IAM), introduced as part of a compilation framework, executes nets using a stack-based strategy that processes active pairs in a last-in-first-out manner, ensuring deterministic reduction while maintaining the visual integrity of the nets. This machine compiles textual descriptions of nets—specifying agents, ports, and rules—into efficient C code, supporting built-in data types and conditional behaviors for broader applicability in visual languages. The IAM's design leverages the locality of interactions to achieve efficient evaluation, minimizing global state changes during reductions.[22] For concurrent programming, interaction nets model parallel processes through disjoint sub-nets that evolve independently until synchronization points, promoting true concurrency without interference. Synchronization is often handled via theamb operator, which introduces non-deterministic choice and coordination between concurrent branches, as explored in extensions like multiport interaction nets. These extensions allow multiple agents to interact at shared ports, enabling the representation of distributed systems where local rewritings propagate effects efficiently. A key contribution is the establishment of a hierarchy among concurrent variants: multi-rule nets are less expressive than multi-wire or multi-port systems, with the latter providing optimal concurrency support by encoding arbitrary interaction systems.[23]

An illustrative example is the producer-consumer problem, modeled using multiport nets where producer cells generate resources into a shared buffer (represented by a central agent with multiple auxiliary ports), and consumer cells synchronize via amb to access available items without global locking. This setup demonstrates local interactions: productions and consumptions occur in disjoint sub-nets until amb resolves non-deterministically at the buffer, ensuring causal independence and efficient parallel execution. Such models highlight interaction nets' suitability for concurrent systems, where disjointness guarantees no unintended overlaps.[23]

Developments since 2013 include bigraphical nets (or binets), which integrate the hierarchical nesting and site mobility of bigraphs with interaction nets' port-based rewriting, allowing agents to be embedded within others and edges to span boundaries for dynamic reconfiguration. This supports non-binary interactions and parallel reductions, ideal for modeling mobile computations in concurrent and reactive systems, as seen in encodings of the ρ-calculus.[24]

More recent applications as of 2025 include the HVM runtime, which uses interaction combinators for massively parallel evaluation of functional programs, and the Vine programming language, designed specifically around interaction nets for distributed computing.[25][26]

![{\displaystyle t[x:=u]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b2e65fa99a7c681d46f41c8b58cc4d02b7b5b651)

![{\displaystyle \alpha [v_{1},\dots ,v_{m}]\bowtie \beta [w_{1},\dots ,w_{n}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/014774914c4f5f0e916594f86fd6ee30dc525a14)

![{\displaystyle \langle \dots t\dots \ |\ x=u,\Delta \rangle \rightarrow \langle \dots t[x:=u]\dots \ |\ \Delta \rangle }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/745dbafb888b76547de986c6d04d4074d04c7600)

![{\displaystyle \langle {\vec {t}}\ |\ x=u,t=w,\Delta \rangle \rightarrow \langle {\vec {t}}\ |\ t[x:=u]=w,\Delta \rangle }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/97231863f84843cbe59ed135ed0dc5571ff6f79b)

![{\displaystyle \epsilon \bowtie \alpha [\epsilon ,\dots ,\epsilon ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/64412d3fa187028b991f8a4e2bbac81e41c2effb)

![{\displaystyle \delta [\alpha (x_{1},\dots ,x_{n}),\alpha (y_{1},\dots ,y_{n})]\bowtie \alpha [\delta (x_{1},y_{1}),\dots ,\delta (x_{n},y_{n})]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f7f424403a7a9c6b4c0d9942a4980e69f0a403fa)

![{\displaystyle \delta [x,y]\bowtie \delta [x,y]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e9e367c7553220dbd80243582db94f8d5806fad1)

![{\displaystyle \gamma [x,y]\bowtie \gamma [y,x]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/efc29c4bf4004628db3efd6146f26edc276eec86)