Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

MAC address

View on Wikipedia

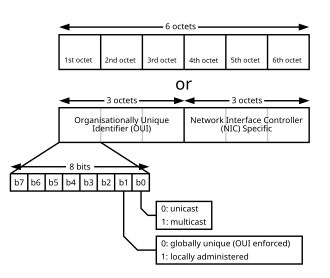

A MAC address (medium access control address or media access control address) is a unique identifier assigned to a network interface controller (NIC) for use as a network address in communications within a network segment. This use is common in most IEEE 802 networking technologies, including Ethernet, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth. Within the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) network model, MAC addresses are used in the medium access control protocol sublayer of the data link layer. As typically represented, MAC addresses are recognizable as six groups of two hexadecimal digits, separated by hyphens, colons, or without a separator.

MAC addresses are primarily assigned by device manufacturers, and are therefore often referred to as the burned-in address, or as an Ethernet hardware address, hardware address, or physical address. Each address can be stored in the interface hardware, such as its read-only memory, or by a firmware mechanism. Many network interfaces, however, support changing their MAC addresses. The address typically includes a manufacturer's organizationally unique identifier (OUI). MAC addresses are formed according to the principles of two numbering spaces based on extended unique identifiers (EUIs) managed by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): EUI-48—which replaces the obsolete term MAC-48—and EUI-64.

Network nodes with multiple network interfaces, such as routers and multilayer switches, must have a unique MAC address for each network interface in the same network. However, two network interfaces connected to two different networks can share the same MAC address.

Address details

[edit]

The IEEE 802 MAC address originally comes from the Xerox Network Systems Ethernet addressing scheme.[1] This 48-bit address space contains potentially 248 (over 281 trillion) possible MAC addresses. The IEEE manages the allocation of MAC addresses, originally known as MAC-48 and now called EUI-48 identifiers. The IEEE has a target lifetime of 100 years (until 2080) for applications using EUI-48 space and restricts applications accordingly. The IEEE encourages adoption of the more plentiful EUI-64 for non-Ethernet applications.[2]

The distinctions between EUI-48 and MAC-48 identifiers are in name and application only. MAC-48 was used to address hardware interfaces within existing 802-based networking applications; EUI-48 is now used for 802-based networking and is also used to identify other devices and software, for example Bluetooth.[3][4] The IEEE now considers MAC-48 to be an obsolete term.[5] EUI-48 is now used in all cases. In addition, the EUI-64 numbering system originally encompassed both MAC-48 and EUI-48 identifiers by a simple translation mechanism.[3][a] These translations have since been deprecated.[3]

The Individual Address Block (IAB) is an inactive registry which has been replaced by the MA-S (MAC address block, small), previously named OUI-36, and has no overlaps in addresses with the IAB[6] registry product as of January 1, 2014. The IAB uses an OUI from the MA-L (MAC address block, large) registry, previously called the OUI registry. The term OUI is still in use,[6] but the IEEE Registration Authority does not administer them. An OUI is concatenated with 12 additional IEEE-provided bits (for a total of 36 bits), leaving only 12 bits for the organisation owning the IAB to assign to its (up to 4096) individual devices. An IAB is ideal for organizations requiring not more than 4096 unique 48-bit numbers (EUI-48). Unlike an OUI, which allows the assignee to assign values in various number spaces (for example, EUI-48, EUI-64, and the various context-dependent identifier number spaces, as in SNAP or EDID), the Individual Address Block could only be used to assign EUI-48 identifiers. All other potential uses based on the OUI from which the IABs are allocated are reserved and remain the property of the IEEE Registration Authority. Between 2007 and September 2012, the OUI value 00:50:C2 was used for IAB assignments. After September 2012, the value 40:D8:55 was used. Owners of an already assigned IAB may continue to use it.[7]

The MA-S registry includes, for each registrant, both a 36-bit unique number used in some standards and a block of EUI-48 and EUI-64 identifiers (while the registrant of an IAB cannot assign an EUI-64). MA-S does not include assignment of an OUI.

Additionally, the MA-M (MAC address block, medium) provides both 220 EUI-48 identifiers and 236 EUI-64 identifiers, the first 28 bits being assigned by IEEE. The first 24 bits of the assigned MA-M block are an OUI assigned to IEEE that will not be reassigned, so the MA-M does not include assignment of an OUI.

Universal vs. local (U/L bit)

[edit]Addresses can either be universally administered addresses (UAA) or locally administered addresses (LAA). A universally administered address is uniquely assigned to a device by its manufacturer. The first three octets (in transmission order) identify the organization that issued the identifier and are known as the organizationally unique identifier (OUI).[3] The remainder of the address (three octets in EUI-48 or five in EUI-64) are assigned by that organization in nearly any manner they please, subject to the constraint of uniqueness. A locally administered address is assigned to a device by software or a network administrator, overriding the burned-in address of a physical device.

Locally administered addresses are distinguished from universally administered addresses by setting (assigning the value of 1 to) the second-least-significant bit of the first octet of the address. This bit is also referred to as the U/L bit, short for Universal/Local, which identifies how the address is administered.[8][self-published source?][9]: 20 If the bit is 0, the address is universally administered, which is why this bit is 0 in all UAAs. If it is 1, the address is locally administered. In the example address 06-00-00-00-00-00, the first octet is 06 (hexadecimal), the binary form of which is 00000110, where the second-least-significant bit is 1. Therefore, it is a locally administered address.[10] Even though many hypervisors manage dynamic MAC addresses within their own OUI, often it is useful to create an entire unique MAC within the LAA range.[11]

Universal addresses that are administered locally

[edit]In virtualisation, hypervisors such as QEMU and Xen have their own OUIs. Each new virtual machine is started with a MAC address set by assigning the last three bytes to be unique on the local network. While this is local administration of MAC addresses, it is not an LAA in the IEEE sense.

A historical example of this hybrid situation is the DECnet protocol, where the universal MAC address (with Digital Equipment Corporation's OUI AA-00-04) is administered locally. The DECnet software sets the last three bytes of the complete MAC address to 00-XX-YY (so that the full MAC address is AA-00-04-00-XX-YY), where XX-YY reflects the host's DECnet network address xx.yy. This eliminates the need for DECnet to have an address resolution protocol since the MAC address of any DECnet host can be determined from its DECnet address.

Unicast vs. multicast (I/G bit)

[edit]The least significant bit of an address's first octet is referred to as the I/G, or Individual/Group, bit.[8][self-published source?][9]: 20 When this bit is 0 (zero), the frame is meant to reach only one receiving network interface.[12] This type of transmission is called unicast. A unicast frame is transmitted to all nodes within the collision domain. In a modern wired setting (i.e. with switches, not simple hubs) the collision domain usually is the length of the Ethernet cabling between two network interfaces. In a wireless setting, the collision domain is all receivers that can detect a given wireless signal. If a switch does not know which port leads to a given MAC address, the switch will forward a unicast frame to all of its ports (except the originating port), an action known as unicast flood.[13][self-published source?] Only the node with the matching hardware MAC address will (normally) accept the frame; network interfaces with non-matching MAC-addresses ignore the frame unless they are in promiscuous mode.

If the least significant bit of the first octet is set to 1 (i.e. the second hexadecimal digit is odd) the frame will still be sent only once; however, network interface controllers will choose to accept or ignore it based on criteria other than the matching of their individual MAC addresses: for example, based on a configurable list of accepted multicast MAC addresses. This is called multicast addressing.

The IEEE has built in several special address types to allow more than one network interface card to be addressed at one time:

- Packets sent to the broadcast address, all one bits, are received by all stations on a local area network. In hexadecimal the broadcast address would be FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF. A broadcast frame is flooded and is forwarded to and accepted by all other nodes.

- Packets sent to a multicast address are received by all stations on a LAN that have been configured to receive packets sent to that address.

- Functional addresses identify one or more Token Ring NICs that provide a particular service, defined in IEEE 802.5.

These are all examples of group addresses, as opposed to individual addresses; the least significant bit of the first octet of a MAC address distinguishes individual addresses from group addresses. That bit is set to 0 in individual addresses and set to 1 in group addresses. Group addresses, like individual addresses, can be universally administered or locally administered.

Ranges of group and locally administered addresses

[edit]The U/L and I/G bits are handled independently, and there are instances of all four possibilities.[10] IPv6 multicast uses locally administered, multicast MAC addresses in the range 33-33-XX-XX-XX-XX (with both bits set).[14]: §2.3.1

Given the locations of the U/L and I/G bits, they can be discerned in a single digit in common MAC address notation as shown in the following table:

U/L I/G

|

Universally administered | Locally administered |

|---|---|---|

| Unicast (individual) | X0-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX X4-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX X8-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX XC-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX |

X2-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX X6-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX XA-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX XE-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX |

| Multicast (group) | X1-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX X5-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX X9-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX XD-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX |

X3-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX X7-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX XB-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX XF-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX |

IEEE 802c local MAC address usage

[edit]IEEE standard 802c[15] further divides the locally administered MAC address block into four quadrants. This additional partitioning is called Structured Local Address Plan (SLAP) and its usage is optional.

| MAC address | Quadrant name | Identifier | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| XA-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX | Extended local | ELI | Assigned by IEEE, but uses a unique 3-octet company ID (CID) instead of an OUI. |

| XE-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX | Standard assigned | SAI | For use in the forthcoming IEEE P802.1CQ specification, to be assigned dynamically by the Block Address Registration and Claiming (BARC) protocol. |

| X2-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX | Administratively assigned | AAI | Can be randomly or arbitrarily assigned to devices. |

| X6-XX-XX-XX-XX-XX | Reserved | Reserved | Reserved for future use, but may be used similarly to AAI until an IEEE specification utilizes this space. |

Applications

[edit]The following network technologies use the EUI-48 identifier format:

- IEEE 802 networks

- Ethernet

- 802.11 wireless networks (Wi-Fi)

- Bluetooth

- IEEE 802.5 Token Ring

- Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI)

- Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM), switched virtual connections only, as part of an NSAP address

- Fibre Channel and Serial Attached SCSI (as part of a World Wide Name)

- The ITU-T G.hn standard, which provides a way to create a high-speed (up to 1 gigabit/s) local area network using existing home wiring (power lines, phone lines and coaxial cables). The G.hn Application Protocol Convergence (APC) layer accepts Ethernet frames that use the EUI-48 format and encapsulates them into G.hn Medium Access Control Service Data Units (MSDUs).

Every device that connects to an IEEE 802 network (such as Ethernet and Wi-Fi) has an EUI-48 address. Common networked consumer devices such as PCs, smartphones and tablet computers use EUI-48 addresses.

EUI-64 identifiers are used in:

- IEEE 1394 (FireWire)

- InfiniBand

- IPv6 (Modified EUI-64 as the least-significant 64 bits of a unicast network address or link-local address when stateless address autoconfiguration is used.)[16] IPv6 uses a modified EUI-64, treats MAC-48 as EUI-48 instead (as it is chosen from the same address pool) and inverts the local bit.[b] This results in extending MAC addresses (such as IEEE 802 MAC address) to modified EUI-64 using only FF-FE (and never FF-FF) and with the local bit inverted.[14]: sec. 2.2.1

- Zigbee / 802.15.4 / 6LoWPAN wireless personal-area networks

- IEEE 11073-20601 (IEEE 11073-20601 compliant medical devices)[17]

Use in hosts

[edit]On broadcast networks, such as Ethernet, the MAC address is expected to uniquely identify each node on that segment and allows frames to be marked for specific hosts. It thus forms the basis of most of the link layer (OSI layer 2) networking upon which upper-layer protocols rely to produce complex, functioning networks.

Many network interfaces support changing their MAC address. On most Unix-like systems, the command utility ifconfig may be used to remove and add link address aliases. For instance, the active ifconfig directive may be used on NetBSD to specify which of the attached addresses to activate.[18] Hence, various configuration scripts and utilities permit the randomization of the MAC address at the time of booting or before establishing a network connection.

Changing MAC addresses is necessary in network virtualization. In MAC spoofing, this is practiced in exploiting security vulnerabilities of a computer system. Some modern operating systems, such as Apple iOS and Android, especially in mobile devices, are designed to assign a random MAC address to their network interface when scanning for wireless access points to avert tracking systems.[19][20]

In Internet Protocol (IP) networks, the MAC address of an interface corresponding to an IP address may be queried with the Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) for IPv4 and the Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP) for IPv6. Thus ARP and NDP relate OSI layer 3 addresses to layer 2 addresses.

Tracking

[edit]Randomization

[edit]According to Edward Snowden, the US National Security Agency has a system that tracks the movements of mobile devices in a city by monitoring MAC addresses.[21] To avert this practice, Apple started using random MAC addresses in iOS devices while scanning for networks.[19] Other vendors quickly followed suit. MAC address randomization during scanning was added in Android starting from version 6.0,[20] in Windows 10,[22] and in Linux 3.18.[23] The actual implementations of the MAC address randomization technique vary largely in different devices.[24] Moreover, various flaws and shortcomings in these implementations may allow an attacker to track a device even if its MAC address is changed, for instance its probe requests' other elements,[25][26] or their timing.[27][24] If random MAC addresses are not used, researchers have confirmed that it is possible to link a real identity to a particular wireless MAC address.[28]

Randomized MAC addresses can be identified by the "locally administered" bit described above.[29]

Other information leakage

[edit]Using wireless access points in SSID-hidden mode (network cloaking), a mobile wireless device may not only disclose its own MAC address when traveling, but even the MAC addresses associated to SSIDs the device has already connected to, if they are configured to send these as part of probe request packets. Alternatives to prevent this include configuring access points to be in either beacon-broadcasting mode or probe-response-with-SSID mode. In these modes, probe requests may be unnecessary or sent in broadcast mode without disclosing the identity of previously known networks.[30]

Anonymization

[edit]Notational conventions

[edit]The standard (IEEE 802) format for printing EUI-48 addresses in human-friendly form is six groups of two hexadecimal digits, separated by hyphens (-) in transmission order (e.g. 01-23-45-67-89-AB). This form is also commonly used for EUI-64 (e.g. 01-23-45-67-89-AB-CD-EF).[3] Other conventions include six groups of two hexadecimal digits separated by colons (:) (e.g. 01:23:45:67:89:AB), and three groups of four hexadecimal digits separated by dots (.) (e.g. 0123.4567.89AB); again in transmission order.[31]

Bit-reversed notation

[edit]The standard notation, also called canonical format, for MAC addresses is written in transmission order with the least significant bit of each byte transmitted first, and is used in the output of the ifconfig, ip address, and ipconfig commands, for example.

However, since IEEE 802.3 (Ethernet) and IEEE 802.4 (Token Bus) send the bytes (octets) over the wire, left-to-right, with the least significant bit in each byte first, while IEEE 802.5 (Token Ring) and IEEE 802.6 (FDDI) send the bytes over the wire with the most significant bit first, confusion may arise when an address in the latter scenario is represented with bits reversed from the canonical representation. For example, an address in canonical form 12-34-56-78-9A-BC would be transmitted over the wire as bits 01001000 00101100 01101010 00011110 01011001 00111101 in the standard transmission order (least significant bit first). But for Token Ring networks, it would be transmitted as bits 00010010 00110100 01010110 01111000 10011010 10111100 in most-significant-bit–first order. The latter might be incorrectly displayed as 48-2C-6A-1E-59-3D. This is referred to as bit-reversed order, non-canonical form, MSB format, IBM format, or Token Ring format.[32]

See also

[edit]- Hot Standby Router Protocol

- MAC filtering

- Network management

- Sleep Proxy Service, which may spoof another device's MAC address during certain periods

- Transparent bridging

- Virtual Router Redundancy Protocol

Notes

[edit]- ^ To convert a MAC-48 into an EUI-64, copy the OUI, append the two octets FF-FF and then copy the organization-specified extension identifier. To convert an EUI-48 into an EUI-64, the same process is used, but the sequence inserted is FF-FE.[3] In both cases, the process could be trivially reversed when necessary. Organizations issuing EUI-64s were cautioned against issuing identifiers that could be confused with these forms.

- ^ With local identifiers indicated with a zero bit, locally assigned EUI-64 begin with leading zeroes and it is easier for administrators to type locally assigned IPv6 addresses based on the modified EUI-64

References

[edit]- ^

IEEE Std 802-2001 (PDF). The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. (IEEE). 2002-02-07. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7381-2941-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 29, 2003. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

The universal administration of LAN MAC addresses began with the Xerox Corporation administering Block Identifiers (Block IDs) for Ethernet addresses.

- ^ "Use of EUI-64 for New Designs". www.ieee802.org. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- ^ a b c d e f "Guidelines for Use of Extended Unique Identifier (EUI), Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI), and Company ID (CID)" (PDF). IEEE Standards Association. IEEE. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ "IEEE-SA – IEEE Registration Authority". IEEE. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- ^ "MAC Address Block Small (MA-S)". Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ a b "IEEE-SA – IEEE Registration Authority". IEEE. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ "IEEE-SA – IEEE Registration Authority". IEEE. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- ^ a b "Ethernet frame IG/LG bit explanation – Wireshark". networkengineering.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- ^ a b R. Hinden; S. Deering (February 2006). IP Version 6 Addressing Architecture. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC4291. RFC 4291. Draft Standard. Obsoletes RFC 3513. Updated by RFC 5952, 6052, 7136, 7346, 7371 and 8064.

- ^ a b "Standard Group MAC Addresses: A Tutorial Guide" (PDF). IEEE-SA. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- ^ "Generating a New Unique MAC Address". RedHat. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ "Guidelines for Fibre Channel Use of the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI)" (PDF). IEEE-SA. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ^ "Overview of Layer 2 Switched Networks and Communication | Getting Started with LANs | Cisco Support Community | 5896 | 68421". supportforums.cisco.com. 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ^ a b D. Eastlake, 3rd; J. Abley (October 2013). IANA Considerations and IETF Protocol and Documentation Usage for IEEE 802 Parameters. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC7042. ISSN 2070-1721. BCP 141. RFC 7042. Best Current Practice 141. Obsoletes RFC 5342. Updates RFC 2153.

- ^ "Local MAC Addresses in the Overview and Architecture based on IEEE Std 802c" (PDF). IEEE-SA. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ^ S. Thomson; T. Narten; T. Jinmei (September 2007). IPv6 Stateless Address Autoconfiguration. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC4862. RFC 4862. Draft Standard. Obsoletes RFC 2462. Updated by RFC 7527.

- ^ IEEE P11073-20601 Health informatics—Personal health device communication Part 20601: Application profile—Optimized Exchange Protocol

- ^ "ifconfig(8) manual page". Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ a b Mamiit, Aaron (2014-06-12). "Apple Implements Random MAC Address on iOS 8. Goodbye, Marketers". Tech Times. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- ^ a b "Android 6.0 Changes". Android developers. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ Bamford, James (2014-08-13). "The Most Wanted Man in the World". Wired. p. 4. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- ^ Winkey Wang. "Wireless networking in Windows 10".

- ^ Emmanuel Grumbach. "iwlwifi: mvm: support random MAC address for scanning". Linux commit effd05ac479b. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ a b Célestin Matte (December 2017). Wi-Fi Tracking: Fingerprinting Attacks and Counter-Measures. 2017 (Theses). Université de Lyon. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ Vanhoef, Mathy; Matte, Célestin; Cunche, Mathieu; Cardoso, Leonardo; Piessens, Frank (10 June 2016). "Why MAC Address Randomization is not Enough: An Analysis of Wi-Fi Network Discovery Mechanisms". Proceedings of the 11th ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security. pp. 413–424. doi:10.1145/2897845.2897883. ISBN 978-1-4503-4233-9. S2CID 12706713. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Martin Jeremy and Mayberry Travis and Donahue Collin and Foppe Lucas and Brown Lamont and Riggins Chadwick and Rye Erik C and Brown Dane. "A study of MAC address randomization in mobile devices and when it fails" (PDF). 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-22. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ Matte Célestin and Cunche Mathieu and Rousseau Franck and Vanhoef Mathy (2016-07-18). "Defeating MAC address randomization through timing attacks". Proceedings of the 9th ACM Conference on Security & Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks. pp. 15–20. doi:10.1145/2939918.2939930. ISBN 9781450342704. S2CID 2625583. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ Cunche, Mathieu (2014). "I know your MAC Address: Targeted tracking of individual using Wi-Fi". Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques. 10 (4): 219–227. doi:10.1007/s11416-013-0196-1. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 19 December 2014. Alt URL

- ^ Nayak, Seema (14 March 2022). "Randomized and Changing MAC (RCM)". Cisco Blogs.

To improve end-user privacy, various operating system vendors (Apple iOS 14, Android 10 and Windows 10) are enabling the use of the locally administered mac address (LAA), also referred to as the random mac address for WIFI operation. When wireless endpoint is associated with random mac address, the MAC address of the endpoint changes over time.

- ^ "Hidden network no beacons". security.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "Agentless Host Configuration Scenario". Configuration Guide for Cisco Secure ACS 4.2. Cisco. February 2008. Archived from the original on 2016-08-02. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

You can enter the MAC address in the following formats for representing MAC-48 addresses in human-readable form: six groups of two hexadecimal digits, separated by hyphens (-) in transmission order,[...]six groups of two separated by colons (:),[...]three groups of four hexadecimal digits separated by dots (.)...

- ^ T. Narten; C. Burton (December 1998). A Caution On The Canonical Ordering Of Link-Layer Addresses. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC2469. RFC 2469. Informational.

External links

[edit]- IEEE Registration Authority Tutorials

- IEEE Registration Authority – Frequently Asked Questions

- IEEE Public OUI and Company ID, etc. Assignment lookup

- IEEE Public OUI/MA-L list

- IEEE Public OUI-28/MA-M list

- IEEE Public OUI-36/MA-S list

- IEEE Public IAB list

- IEEE IAB and OUI MAC Address Lookup Database and API

- IANA list of Ethernet Numbers

- Wireshark's OUI Lookup Tool

MAC address

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Early Development

The concept of the MAC address emerged from the early design of Ethernet, a local area network technology developed at Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) to interconnect computers using coaxial cable for high-speed data sharing.[11] On May 22, 1973, engineer Robert Metcalfe authored an internal memo outlining the potential for such a network, drawing inspiration from the ALOHAnet packet radio system and emphasizing collision avoidance in shared media access.[12] Collaborating with David Boggs, Metcalfe implemented the first experimental Ethernet system, which successfully transmitted packets between two computers on November 11, 1973, operating at 2.94 Mbps over 1 km of cable.[13] Central to this prototype was a 48-bit hardware addressing scheme for uniquely identifying network interfaces, or "stations," on the bus topology, enabling frame delivery and supporting the carrier-sense multiple access with collision detection (CSMA/CD) protocol to manage contention.[14] The choice of 48 bits provided scalability for millions of devices, with the structure allocating the first 24 bits for vendor-specific identifiers and the remainder for unique serial numbers, a division that facilitated global uniqueness without centralized coordination at the time.[15] Early tests connected Xerox Alto personal computers, demonstrating reliable packet transmission amid collisions, though initial speeds were limited by the prototype's custom interface boards.[11] Further refinement occurred through iterative prototyping at PARC throughout the 1970s, incorporating error detection via cyclic redundancy checks and evolving the addressing to handle multicast and broadcast frames for efficient group communication.[16] In 1979, Xerox formed the DIX alliance with Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and Intel to commercialize the technology, culminating in the Ethernet Specification Version 1.0 released in September 1980, which standardized the 48-bit "physical station address" at 10 Mbps over thick coaxial cable.[15] This version retained the core addressing mechanism from PARC's work, emphasizing burned-in, non-routable identifiers tied to the physical layer for low-level medium access control.[17]IEEE Standardization

The IEEE 802 Local and Metropolitan Area Networks Standards Committee was formed in February 1980 to develop interoperable standards for data link and physical layers in LANs and MANs, including the addressing mechanisms that became known as MAC addresses. This effort built upon the 48-bit physical address format from the earlier DIX Ethernet specification (1980) by Digital Equipment Corporation, Intel, and Xerox, adapting it for the MAC sublayer of the IEEE 802 reference model. The committee's work emphasized ensuring address uniqueness to support collision-free communication in shared media environments.[18][19] IEEE Std 802.3, the first standard incorporating the 48-bit address for Ethernet, was approved on June 8, 1983, by the IEEE 802 committee. This standard specified 48-bit destination and source addresses within Ethernet frames, transmitted least significant bit first (little-endian octet order), with the first 24 bits reserved for manufacturer-assigned identifiers to guarantee global uniqueness. Subsequent standards, such as IEEE Std 802.11 for wireless LANs (initially published in 1997), extended the same 48-bit MAC format across diverse physical layers while maintaining compatibility.[19][15] To administer assignments, the IEEE Registration Authority was established as part of the 802 standardization process, allocating 24-bit Organizationally Unique Identifiers (OUIs) to vendors for the first half of MAC addresses. This mechanism, operational from the early 1980s, prevents duplication by requiring vendors to register and incorporate OUIs into devices, with the remaining 24 bits vendor-specific. The IEEE later formalized the 48-bit structure as Extended Unique Identifier-48 (EUI-48) in standards like IEEE Std 802-2001, distinguishing universally administered (globally unique) from locally administered addresses via the second least significant bit of the first octet.[20][21]Evolution and Modern Extensions

Following the establishment of 48-bit MAC addresses (EUI-48) in early IEEE 802 standards during the 1980s, subsequent developments addressed the need for longer identifiers in emerging protocols. The EUI-64 format emerged in the 1990s as an extension mechanism, concatenating a 24-bit Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI) with a 40-bit extension or deriving it by inserting the fixed value 0xFFFE between the first three and last three octets of an EUI-48 while flipping the second-least significant bit of the first octet to indicate local scope.[6] This format supported applications such as IPv6 stateless address autoconfiguration (SLAAC), where the interface identifier portion of the IPv6 address could be generated from the MAC address.[22] However, direct mapping from EUI-48 to EUI-64 has been deprecated since the mid-2010s in favor of distinct EUI-64 assignments by the IEEE Registration Authority to avoid unintended universal address generation and ensure proper uniqueness.[23] In response to growing device densities and the limitations of universal address spaces in local networks, IEEE Std 802c, approved on August 25, 2017, amended the IEEE 802 Overview and Architecture to define structured local MAC address pools.[24] This standard designates ranges within the locally administered address space (second bit set to 1) for protocols using Company IDs (CIDs) assigned by the IEEE Registration Authority, enabling multiple independent administrations to manage unique local identifiers without collision risks across bridged domains.[25] It specifies formats for administratively assigned individual (AAI) and group addresses, ensuring compatibility with existing IEEE 802 media access control while supporting scalability in environments like large-scale IoT deployments.[26] Privacy considerations have driven further extensions since the 2010s, as fixed MAC addresses enable persistent device tracking across networks via probe requests and association frames. To mitigate this, IEEE 802.11 initiated the Randomized and Changing MAC Addresses (RCMAC) Study Group in 2016, leading to amendments that standardize temporary randomized addresses for unauthenticated Wi-Fi scanning and probing, distinct from the stable interface MAC.[27] Operating systems implemented these practices earlier; for instance, Apple introduced randomized MACs for Wi-Fi scans in iOS 8 (released September 17, 2014) and macOS Sierra (released September 20, 2016) when not associated with a network.[28] Similar randomization, often rotating per session or network, became default in Android from version 10 (released September 3, 2019), reducing traceability while preserving network functionality through persistent identifiers for active connections.[29] These changes prioritize causal unlinkability in transient interactions over static hardware binding, though they complicate legacy network management reliant on fixed MACs.[30]Technical Structure

Format and Composition

A MAC address, designated as an EUI-48 or MAC-48 identifier in IEEE standards, comprises 48 bits organized into six octets.[31] It is conventionally represented in hexadecimal format using 12 characters, divided into six pairs separated by colons or hyphens, such as00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E.[21] This notation facilitates readability, with each pair corresponding to one octet.[32]

The structure allocates the first three octets (24 bits) to the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI), a code assigned by the IEEE to manufacturers for uniquely identifying their devices.[31] The remaining three octets form the manufacturer-assigned portion, ensuring uniqueness within the vendor's product line.[21]

Within the first octet, specific bits define address properties: the least significant bit (bit 0, or I/G bit) distinguishes unicast addresses (0) from group or multicast addresses (1), while the second-least significant bit (bit 1, or U/L bit) indicates universally administered addresses (0, globally unique via IEEE) versus locally administered addresses (1, set by network administrators).[32] These flags enable protocols to handle addressing modes appropriately in IEEE 802 networks.[21]

Variations in representation exist, including dashed separators or no delimiters (e.g., 001A2B3C4D5E), but the IEEE recommends canonical forms for interoperability, such as lowercase hexadecimal with colons in certain contexts like YANG data models.[8] The bit ordering follows the standard octet transmission sequence in Ethernet frames, with the first octet sent first.[32]

Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI)

The Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI) is a 24-bit value assigned by the IEEE Registration Authority to uniquely identify an organization, such as a manufacturer or vendor of networking equipment.[6][20] In the context of 48-bit addresses like MAC-48 or EUI-48, the OUI occupies the initial three octets, forming the prefix that distinguishes the assigning organization from others worldwide.[6] The remaining 24 bits serve as an extension identifier, which the OUI assignee must allocate uniquely to individual devices or interfaces to ensure global address uniqueness.[6][20] Assignment of an OUI occurs as part of a MAC Address Block Large (MA-L) registration, where organizations apply through the IEEE Registration Authority's online portal.[20] The process requires payment of a one-time fee of US $3,480 for public listings, plus potential additional costs such as a US $200 contract fee, with applications typically processed within seven business days.[20] Confidentiality for the assignment incurs an annual renewal fee of US $4,020.[20] Once assigned, the OUI cannot be altered or reassigned by the holder, and extensions must conform to IEEE rules to avoid duplication, such as reserving specific bit patterns for group addresses or local use.[6] This identifier underpins the hierarchical structure of MAC addresses in IEEE 802 networks, enabling vendors to produce billions of unique device identifiers (2^24 per OUI) without overlap.[20] Public OUI listings are maintained by the IEEE for lookup and verification, aiding in device identification and forensic analysis in networking.[20] Extensions of the OUI concept, such as OUI-36 for smaller blocks, allow finer-grained assignments but retain the core 24-bit organizational prefix for compatibility.[20]Address Bits and Flags

A standard MAC address, also known as a MAC-48 or EUI-48 identifier, comprises 48 bits divided into six octets, with the first octet containing two key flag bits that define the address's scope and type.[6] The least significant bit (bit 0) of this octet is the Individual/Group (I/G) bit: it is set to 0 for unicast addresses targeting a single network interface and to 1 for group addresses, which include multicast addresses delivered to multiple interfaces or the broadcast address (all bits set to 1) delivered to all interfaces on the local network segment.[6] [33] The second least significant bit (bit 1) is the Universal/Local (U/L) bit, which distinguishes between globally administered addresses and locally administered ones: a value of 0 indicates a universal address assigned by the IEEE through its Registration Authority, ensuring uniqueness across manufacturers, while a 1 denotes a local address configured by network administrators, which may override the manufacturer-assigned identifier but risks collisions if not managed carefully within the local scope.[6] [34] For universal addresses (U/L=0), the upper 24 bits (including bits 2 through 7 of the first octet) form the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI), allocated to vendors by the IEEE, with the remaining 24 bits vendor-specific; setting the U/L bit to 1 allows reuse of the OUI space locally without global uniqueness guarantees.[6] These flags enable efficient frame processing in IEEE 802 networks: receiving interfaces can quickly filter frames based on the I/G bit before deeper inspection, and the U/L bit supports flexible address management in scenarios like virtualization or privacy-enhanced randomization, where devices periodically change local MAC addresses to mitigate tracking.[34] The combination of these bits reserves specific address spaces—for instance, universal unicast addresses occupy the quadrant where both bits are 0—while prohibiting certain patterns, such as universal group addresses with I/G=1 and U/L=0 in standard assignments to avoid conflicts with multicast protocols.[35]Variations in Length and Form

The primary lengths for Extended Unique Identifiers (EUIs) used as MAC addresses are 48 bits for EUI-48 (also known as MAC-48) and 64 bits for EUI-64, as specified by the IEEE for unique network interface identification across its 802 standards family.[21][6] EUI-48 consists of 6 octets (48 bits total), typically represented in hexadecimal as six pairs of digits separated by colons (e.g., 00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E), providing a total address space of approximately 2^48 unique identifiers, with the first 24 bits allocated as the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI) and the remaining 24 bits for manufacturer-specific extensions.[21][36] EUI-64 extends to 8 octets (64 bits), represented similarly in hexadecimal but with eight pairs (e.g., 02-1A-2B-FF-FE-3C-4D-5E), designed to support larger-scale networks and protocols requiring more identifiers, such as certain IEEE 802 wireless and personal area network standards beyond traditional Ethernet.[21][6] This format often incorporates a 24-bit OUI followed by a 40-bit extension or, in derivation from EUI-48, inserts the fixed sequence FF:FE between the OUI-derived and device-specific portions while flipping the universal/local bit for compatibility with IPv6 interface identifiers per RFC 4291.[36][22] IEEE recommends EUI-64 for new designs needing globally unique addresses to future-proof against exhaustion of the 48-bit space, though EUI-48 remains dominant in wired Ethernet (IEEE 802.3) deployments.[37] Less common forms include EUI-60 (60 bits), allocated for specific high-capacity applications, but these are not widely adopted as standard MAC addresses in most networking protocols.[6] Variations in form also encompass bit-level flags: the second-least significant bit of the first octet indicates universal (0, IEEE-assigned) versus local (1, administrator-assigned) administration, while the least significant bit distinguishes individual addresses (0) from group/multicast addresses (1), applicable to both lengths for ensuring uniqueness and scope in layer-2 communications.[21] Transmission may use non-canonical bit ordering in some media (e.g., token ring), but canonical order (least significant bit first within each octet) is standard for representation and assignment.[31]Assignment and Administration

Global Assignment by IEEE

The IEEE Standards Association's Registration Authority administers the global assignment of MAC addresses, ensuring their uniqueness across worldwide networks through the allocation of address blocks to manufacturers and organizations.[38] These assignments follow IEEE 802 standards, where the first 24 bits of a 48-bit MAC address form the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI), uniquely identifying the assignee, while the remaining 24 bits are controlled by the assignee for device-specific identification.[20] The process requires applicants to submit detailed applications specifying intended use, after which the Authority reviews and assigns identifiers from available pools, prohibiting applicant-specified values to maintain impartiality.[39] Assignments are categorized by size to accommodate varying needs: MA-L for large blocks providing a full OUI with up to 2^24 individual EUI-48 addresses; MA-M for medium blocks offering subsets of addresses; and MA-S utilizing a 36-bit OUI-36 for smaller allocations, all usable as MAC, Bluetooth, or Ethernet addresses.[5] Globally unique addresses are distinguished by the universal/local (U/L) bit set to 0 in the second least significant bit of the first octet, contrasting with locally administered addresses (U/L=1) managed independently.[6] The public registry at the IEEE site lists assigned OUIs, enabling verification of vendor ownership and preventing duplication.[40] This centralized mechanism, rooted in IEEE 802's framework since its inception in the early 1980s, mitigates address exhaustion by enforcing structured allocation and reserving ranges for special uses, such as multicast (I/G bit=1).[21] Assignees must adhere to guidelines on address usage, including extensions for group addresses, to preserve the integrity of the global namespace.[6] Updates to assignment information require formal requests, ensuring ongoing accuracy in the registry.[41]Local and Group Address Management

Locally administered MAC addresses are distinguished from universally administered ones by the universal/local (U/L) bit, the second-least-significant bit in the first octet, which is set to 1 to indicate local assignment rather than global uniqueness enforced by the IEEE.[24] These addresses are configured by network administrators or device software to override manufacturer-assigned (burned-in) addresses, commonly for virtual machines, containerized environments, or bridging multiple interfaces while maintaining local network compatibility.[42] Unlike globally unique addresses, local ones require no registration with the IEEE Registration Authority and are intended for scope-limited uniqueness within a single administrative domain, such as a LAN segment, to avoid address collisions in that context.[43] Management of locally administered addresses emphasizes administrative responsibility for ensuring uniqueness and avoiding interference with global assignments, as duplication within a broadcast domain can lead to frame delivery failures or loops.[44] The IEEE Std 802c-2017 amendment introduces the Structured Local Address Plan (SLAP), an optional framework partitioning the local address space into quadrants based on the initial octets (e.g., starting with 02-80-... for CID-based local or x2-xx-xx for semantically opaque local), enabling multiple local administrators to coexist without overlap by adhering to defined ranges and protocols for assignment.[24] Protocols like DHCPv6 extensions in RFC 8948 support SLAP by allowing clients or relays to request preferred quadrants, facilitating automated or semi-automated local assignment while preserving collision avoidance.[35] Administrators must verify configurations, such as through tools overriding NIC settings, and monitor for conflicts, particularly in environments with dynamic virtualization where multiple virtual interfaces share a host.[45] Group MAC addresses, identified by the individual/group (I/G) bit—the least-significant bit in the first octet set to 1—designate multicast or broadcast frames for delivery to multiple recipients rather than a single unicast endpoint.[46] Broadcast addresses, fixed as all-1s (FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF), flood frames to all stations in the broadcast domain, while multicast addresses (e.g., 01-00-5E-... for IPv4 mapping) target protocol-defined groups, with the IEEE reserving ranges like 01-80-C2-00-00-0x for spanning tree and other control protocols.[47] Management involves protocol-specific allocation: for IP multicast, the lower 23 bits of the MAC derive from the IP address's lower 23 bits after mapping (dropping the first 4 bits of the IP), supporting up to 32 IP groups per MAC to conserve address space.[48] In practice, group address management relies on network devices like switches implementing IGMP snooping or MLD for IPv6 to prune unnecessary floods, reducing bandwidth waste, while local administrators configure filters or VLANs to scope multicast domains and prevent leakage across segments.[49] The IEEE maintains reserved group ranges to avoid conflicts with unicast or local spaces, ensuring protocols like Ethernet bridging treat them distinctly for forwarding decisions.[50] Both local and group addresses underscore the layered administration in IEEE 802 networks, where global uniqueness yields to flexible, context-aware assignment under local control, provided implementers follow bit conventions and scope rules to maintain reliable Layer 2 operations.[51]Reserved Ranges and Special Cases

The first octet of a MAC address contains two significant bits: the individual/group (I/G) bit, which is the least significant bit (0 for unicast/individual addresses, 1 for group/multicast/broadcast addresses), and the universal/local (U/L) bit, the second least significant bit (0 for universally administered addresses assigned by the IEEE Registration Authority, 1 for locally administered addresses managed by local network administrators without global uniqueness guarantees).[6] These bits enable differentiation between address types, with universally administered addresses ensuring no duplication across manufacturers and locally administered ones allowing flexibility for virtual machines, temporary assignments, or testing while risking local collisions if not coordinated.[6] The all-ones address (FF-FF-FF-FF-FF-FF) serves as the broadcast address, a group address to which all devices on a local network segment respond, commonly used for protocols like ARP requests.[7] The all-zeros address (00-00-00-00-00-00) is generally reserved and invalid for transmission as a destination address in Ethernet frames, though it may appear as a source in specific contexts like unspecified interfaces or loopback simulations, but it does not correspond to a valid hardware identifier.[52] IEEE reserves specific multicast ranges within the group address space for standards-defined protocols, particularly the block 01-80-C2-00-00-00 to 01-80-C2-00-00-0F, which IEEE 802.1D bridges do not forward to prevent unnecessary propagation of control traffic.[7] Within this, addresses like 01-80-C2-00-00-00 designate the Bridge Group for spanning tree and management protocols, while 01-80-C2-00-00-01 to 01-80-C2-00-00-04 handle MAC control and slow protocols.[47] Additional standard group addresses from 01-80-C2-00-00-10 onward support functions like provider bridge operations (e.g., 01-80-C2-00-00-08) and multiple VLAN registration (01-80-C2-00-00-0D), assigned permanently to IEEE 802 standards or affiliates like ISO/IEC for interoperability.[47] These reservations prioritize scarce resources for essential Layer 2 control, ensuring bridges filter them appropriately to maintain network efficiency.[7]| Address | Assignee/Standard | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 01-80-C2-00-00-00 | IEEE 802.1Q/X/AE/AX | Bridge Group address (not forwarded by bridges) |

| 01-80-C2-00-00-01 | IEEE 802.1Q | MAC-specific control protocols |

| 01-80-C2-00-00-02 | IEEE 802.1Q/AX | Slow Protocols Multicast |

| 01-80-C2-00-00-08 | IEEE 802.1Q | Provider Bridge group |

| 09-00-2B-00-00-04 | ISO 9542 | All End System Network Entities |

IEEE 802c Local Usage Guidelines

IEEE Std 802c-2017, published on August 25, 2017, establishes guidelines for the usage of locally administered 48-bit MAC addresses to enable structured assignment and coexistence of multiple address assignment protocols within local networks.[24] These addresses, identified by setting the universal/local (U/L) bit to 1 in the first octet (resulting in second hexadecimal digits of 2, 6, A, or E), form the locally administered space, which constitutes half of the total 48-bit MAC address pool.[24] The standard introduces the Structured Local Address Plan (SLAP), an optional framework that subdivides this space into four quadrants based on two specific bits (Y and Z), facilitating disjoint address pools to prevent collisions among protocols from different administrations, such as IEEE 802 standards, IETF protocols, or local network managers.[26] SLAP designates the quadrants by the value of the second hexadecimal digit of the MAC address, ensuring that protocols can select ranges aligned with their assignment authority while maintaining global compatibility.[26]| Quadrant | Second Hex Digit | Binary (Y Z) | Identifier Type | Usage Description | Available Bits for Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | 2 (0010) | 00 | AAI (Administratively Assigned Identifier) | Arbitrary assignment by local network administrators; protocols must ensure uniqueness within the LAN scope. | 44 bits (~1.8 × 10¹³ addresses)[26] |

| 10 | 6 (0110) | 10 | Reserved | Intended for future administrative use similar to AAI, but with potential reservations for specific protocols; currently available for local assignment with caution to avoid conflicts. | 44 bits[26] |

| 01 | A (1010) | 01 | ELI (Extended Local Identifier) | Assigned using a 24-bit Company ID (CID) from the IEEE Registration Authority, providing ~16.8 million addresses per CID for protocols requiring structured local uniqueness. | 24 bits (CID) + 20 bits (extension)[24][26] |

| 11 | E (1110) | 11 | SAI (Standard Assigned Identifier) | Reserved exclusively for protocols defined in IEEE 802 standards, enabling large-scale assignments (up to 44 bits) without external coordination. | 44 bits (~1.8 × 10¹³ addresses)[24][26] |

Applications in Networking

Role in Layer 2 Communications

Media Access Control (MAC) addresses function at the data link layer (Layer 2) of the OSI model, serving as hardware identifiers for network interfaces to enable direct communication between devices on the same local network segment.[7][54] In this layer, divided into the MAC sublayer for access control and addressing, and the Logical Link Control (LLC) sublayer for flow and error management, MAC addresses facilitate frame-level addressing without reliance on higher-layer protocols like IP.[55] They are 48 bits long in standard Ethernet implementations, with the first 24 bits typically allocated as the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI) by the IEEE, ensuring global uniqueness for individual addresses while supporting local or group variants.[20] In Ethernet frame transmission, the source MAC address identifies the sending device, while the destination MAC address specifies the recipient, allowing Layer 2 devices such as switches to process and forward frames based solely on local topology.[56] Switches maintain a dynamic MAC address table (also known as a forwarding database), learned by inspecting the source MAC address of incoming frames and associating it with the ingress port; upon receiving a frame, the switch examines the destination MAC to determine the egress port, forwarding unicast frames only to that port or flooding to all ports in the same VLAN if the destination is unknown or a broadcast/multicast address.[57][58] This mechanism reduces unnecessary traffic compared to hubs, which broadcast all frames, by enabling selective forwarding that confines communication to the local broadcast domain.[59] MAC addresses delimit the scope of Layer 2 communications to physical or virtual LANs, preventing frames from traversing routers, which operate at Layer 3 using IP addresses; inter-network traffic requires address resolution protocols like ARP to map IP to MAC for the final hop delivery.[4] Special MAC addresses, such as the broadcast address FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF, propagate frames to all devices on the segment for discovery or announcements, while multicast addresses (with the least significant bit of the first octet set to 1) target groups for efficient distribution in protocols like IGMP snooping.[7] This addressing scheme underpins standards like IEEE 802.3 Ethernet, ensuring collision-free or managed access in shared media environments via Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Detection (CSMA/CD) in half-duplex modes.[56]Integration with Protocols like ARP

The Address Resolution Protocol (ARP), standardized in RFC 826 in November 1982, relies on MAC addresses to resolve IPv4 addresses to corresponding hardware addresses within a broadcast domain, enabling Ethernet frames carrying IP packets to reach their local destinations. ARP operates by encapsulating its messages in Ethernet frames, where the source MAC address identifies the querying device and the destination MAC address is set to the broadcast value 01:00:5e:00:00:00 for the link-layer header in requests, ensuring all devices on the segment receive the query. This broadcast mechanism, integral to ARP's design, leverages the universal/local bit in the MAC address (the second-least significant bit of the first octet) to distinguish individual addresses from group communications, though ARP requests specifically use the reserved broadcast form ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff in the payload fields for target hardware addresses during initial resolution. Within the ARP packet structure, fixed fields explicitly include 6-byte hardware addresses for both sender and target, with the sender's MAC populated in requests to allow responders to reply directly via unicast Ethernet framing using that MAC as the destination. In an ARP reply, the queried device's MAC address fills the sender hardware address field, completing the resolution and populating local ARP caches (typically holding up to 256-1024 entries depending on implementation) to avoid repeated broadcasts for subsequent communications. This tight coupling ensures causal linkage between layer-3 IP routing and layer-2 frame delivery, as unresolved MACs prevent frame transmission; empirical network traces confirm ARP failures manifest as packet drops, with broadcast storms possible if caches lack entries or duplicates arise from misconfigurations.[60] Similar integration occurs in related protocols, such as the Inverse ARP (InARP) extension defined in RFC 2390 for non-broadcast media like Frame Relay, where DLCI identifiers map to MAC-equivalent addresses, or proxy ARP in RFC 1027, which allows routers to respond on behalf of remote hosts using their own MAC in replies to mask subnet boundaries. For IPv6, the Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP) in RFC 4861 mirrors ARP by using solicited-node multicast MAC addresses derived from IPv6 targets (e.g., 33:33:xx:xx:xx:xx prefix) for neighbor solicitation messages, embedding link-layer addresses in ICMPv6 options to achieve stateless autoconfiguration and duplicate address detection without relying on broadcast. These protocols underscore MAC addresses' foundational role in address resolution, with deviations (e.g., in virtualized environments per RFC 9161) requiring explicit mediation to preserve interoperability across bridged domains.Usage in Wired and Wireless Standards

In IEEE 802.3 Ethernet standards, which define wired local area network operations across speeds from 1 Mb/s to 400 Gb/s, MAC addresses serve as the primary identifiers at the media access control (MAC) sublayer of the data link layer.[61] Each Ethernet frame includes a 48-bit destination MAC address followed by a 48-bit source MAC address, enabling devices to determine frame delivery within the local network segment.[62] These addresses support unicast communication to specific devices, multicast to groups via addresses with the least significant bit of the first octet set to 1, and broadcast to all devices using the all-ones address (FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF).[38] The IEEE 802.3 frame format relies on these MAC addresses for carrier sense multiple access with collision detection (CSMA/CD) in half-duplex modes or full-duplex operations without contention, ensuring reliable frame transmission over twisted-pair, fiber, or coaxial media.[63] Universally administered MAC addresses, assigned via the IEEE Registration Authority, predominate, though locally administered addresses can be configured for specific network needs.[38] In IEEE 802.11 wireless LAN standards, MAC addresses perform analogous roles but accommodate infrastructure and ad-hoc topologies, with frames supporting up to four 48-bit address fields to handle scenarios involving access points (APs) and stations.[64] The basic service set identifier (BSSID) is typically the AP's MAC address, uniquely identifying the wireless cell, while probe requests and association frames use source and destination MACs for discovery and connection establishment.[65] Unlike Ethernet's two-address frames, 802.11 data frames in infrastructure mode designate fields for receiver (next-hop station), transmitter (forwarding AP), destination (end recipient), and source (originator), facilitating meshed or relayed transmissions.[64] The 802.11 MAC sublayer employs these addresses within carrier sense multiple access with collision avoidance (CSMA/CA) mechanisms, including request-to-send/clear-to-send (RTS/CTS) handshakes that incorporate MACs to mitigate hidden node problems.[66] Multicast and broadcast frames, identified by group addresses, enable efficient distribution to multiple stations, with the standard mandating support for globally unique 48-bit addresses alongside protocol extensions for power management and quality of service.[67] Both wired and wireless standards under IEEE 802 leverage MAC addresses for layer-2 switching and bridging, with Ethernet bridges forwarding based on learned MAC tables and Wi-Fi APs performing similar functions in extended service sets.[38]Security and Privacy Considerations

Device Tracking and Identification Risks

MAC addresses serve as persistent, unique hardware identifiers for network interfaces, enabling the tracking and identification of devices across networks when exposed in unencrypted frames like Wi-Fi probe requests and beacons. These frames, broadcast to discover available networks, reveal the MAC address to any passive listener within radio range, allowing correlation of a single device's movements over time and space without user consent or authentication.[30] This capability has been exploited in various applications, including retail analytics where vendors deploy Wi-Fi sniffers to log MAC addresses for profiling customer behaviors, such as dwell times and visit frequencies, as documented in industry practices since at least 2013.[68] In surveillance contexts, static MAC addresses facilitate targeted individual tracking; for example, a 2013 research demonstration showed how Wi-Fi-based MAC monitoring could compute point-to-point travel times and infer user trajectories in urban environments, extending beyond vehicular traffic to pedestrian device carriers.[68] Government and private entities have leveraged this for broader monitoring, with passive MAC collection at public hotspots enabling device fingerprinting that links hardware to specific users when combined with contextual data like location timestamps or repeated associations.[69] The Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI) portion of the MAC address further aids identification by revealing the manufacturer, narrowing device types (e.g., Apple vs. Android ecosystems) and potentially tying observations to vendor-specific behaviors.[70] These risks are amplified in dense environments like cities or events, where widespread access point deployment creates comprehensive coverage; studies from 2017 onward confirm that non-randomized MACs allow long-term profiling, with probe requests alone sufficient for 80-90% accuracy in re-identifying devices across sessions in controlled tests.[71] Incidents, such as Apple's 2023 revelation of iOS devices inadvertently transmitting true MAC addresses alongside randomized ones in certain Wi-Fi scenarios, underscore implementation flaws that expose users to unintended tracking by network operators or eavesdroppers.[72] Without countermeasures, this exposes individuals to unauthorized surveillance, commercial exploitation, and potential linkage to personal identities via cross-referenced data sources, as evidenced by academic analyses of Wi-Fi analytics distortions from unmitigated MAC persistence.[73]Spoofing Vulnerabilities and Mitigation

MAC address spoofing involves an attacker altering the MAC address transmitted by their network interface to impersonate a legitimate device, exploiting the lack of inherent authentication in Layer 2 Ethernet frames. This vulnerability arises because MAC addresses are not cryptographically protected; operating systems and drivers permit software overrides of the hardware-burned address, enabling tools likeifconfig on Linux or registry edits on Windows to facilitate changes without hardware modification.[74] [75] In IEEE 802.3 Ethernet networks, switches forward frames based solely on learned MAC addresses in their content-addressable memory (CAM) tables, allowing a spoofed address to redirect traffic intended for the original device, as demonstrated in attacks where duplicate MACs cause frame misdirection.[74]

The primary risks include bypassing access control lists (ACLs) that filter by MAC, enabling unauthorized network entry in environments relying on static MAC whitelisting, such as campus or enterprise LANs. Spoofing facilitates ARP poisoning, where gratuitous ARP replies with the spoofed MAC associate an attacker's interface with a victim's IP, enabling man-in-the-middle (MITM) interception of traffic; this has been a vector in documented Layer 2 attacks since at least the early 2000s.[76] [74] In wireless IEEE 802.11 networks, unencrypted management frames exacerbate spoofing, permitting identity forgery for deauthentication attacks or session hijacking, with received signal strength indicator (RSSI) variations often detectable but not always enforced.[77] Such exploits can lead to data exfiltration, denial-of-service via CAM table exhaustion (if combined with flooding), or evasion of intrusion detection systems tuned to known MACs.[75]

Mitigation strategies focus on network-level validation rather than endpoint enforcement, as client-side prevention (e.g., driver-level disabling) is unreliable against rootkits or physical access. Cisco Catalyst switches implement port security to restrict ports to one or a few learned MAC addresses, using "sticky" learning to bind dynamically observed addresses and shut down violating ports; violation modes include protect (silent drop) or restrict (alert and drop), effective against single-spoof attempts but vulnerable to multi-MAC flooding if limits are high.[74] Dynamic ARP Inspection (DAI) cross-checks ARP packets against a DHCP snooping database of IP-MAC-port bindings, discarding mismatches to block spoofed ARP replies, with rate limiting to prevent exhaustion attacks; deployed since IOS versions around 2005, it requires enabling DHCP snooping upstream.[76] [74]

Additional layered defenses include IP Source Guard, which filters inbound traffic by validated IP-MAC bindings from DHCP snooping, and IEEE 802.1X port-based authentication, which ties access to credentials rather than MAC alone, using EAP methods for mutual verification.[74] In wireless contexts, RSSI fingerprinting detects spoofing by correlating signal patterns inconsistent with the claimed device's location, as validated in IEEE 802.11 studies showing over 90% accuracy in controlled environments, though environmental noise reduces efficacy.[77] Network monitoring tools can flag rapid MAC changes or duplicates via syslog or SNMP traps, but comprehensive prevention demands segmenting untrusted ports and avoiding sole reliance on MAC for policy, as no single IEEE standard mandates spoofing resistance due to the address's design for local, non-routable identification.[77] These measures, while reducing attack surface, introduce overhead like increased CPU load on switches during inspection, necessitating careful configuration in high-traffic deployments.[74]

MAC Randomization Implementations

MAC randomization implementations primarily occur at the operating system level for Wi-Fi client devices, generating temporary addresses derived from randomized values within the locally administered MAC address space (second least significant bit of the first octet set to 1) to obscure the device's permanent hardware identifier during network discovery, association, and data exchange phases.[78][79] These implementations typically maintain a consistent randomized MAC per network profile to ensure connectivity stability, while regenerating the address periodically (e.g., every 24 hours or upon disconnection/reassociation) or for entirely new networks to mitigate tracking risks.[80][81] Apple's iOS introduced MAC randomization in version 8.0 (September 2014) initially for probe requests in the unassociated state, but expanded it to the association phase and made it the default for new Wi-Fi networks in iOS 14 (September 2020), iPadOS 14, and subsequent releases including macOS Ventura and later.[82][29] In these systems, each SSID receives a unique randomized MAC, preserved across sessions for the same network but regenerated for untrusted or public ones, with further enhancements in iOS 16.1 (October 2022) extending randomization to additional frame types on supported Wi-Fi chips.[83] Users or administrators can disable it via settings or MDM policies for managed devices, though it remains opt-out only for privacy-focused defaults.[84] Google's Android implemented MAC randomization as an optional developer feature in Android 9 (August 2018), becoming enabled by default for new Wi-Fi networks in Android 10 (September 2019) and standardizing per-network persistence with re-randomization triggers such as every 24 hours, device reboot, or network profile reset.[78][85] The Android Open Source Project specifies that randomized addresses are generated using a hash of network parameters (e.g., SSID and BSSID) combined with a random seed, ensuring uniqueness and avoiding collisions while supporting enterprise features like certificate-based authentication.[80] Device manufacturers may vary exact behaviors, but core randomization applies to both probe and association frames, with options to revert to hardware MAC for specific networks via advanced Wi-Fi settings.[86] Microsoft Windows supports random hardware addresses starting in Windows 10 (version 1803, April 2018), configurable per Wi-Fi network or globally under Settings > Network & Internet > Wi-Fi > Manage known networks > Properties > Privacy, where enabling it substitutes the device's MAC with a randomized one for outbound frames.[87] This feature randomizes during connection to new networks and can be toggled to refresh the address, aiding privacy on public Wi-Fi but potentially complicating network management tools reliant on static identifiers.[88][89] IEEE 802.11 standards do not mandate randomization but acknowledge its prevalence through study groups since 2014, with IETF documents like RFC 9724 (March 2025) cataloging interoperability impacts and recommending network adaptations such as probing for stable identifiers in enterprise environments.[32][90] Implementations across these platforms prioritize locally administered addresses to comply with OUI allocation rules while avoiding interference with globally unique ranges.[38]Criticisms and Trade-offs of Randomization

MAC address randomization, while intended to enhance privacy by obscuring persistent device identifiers, has been criticized for its incomplete protection against tracking. Studies demonstrate that attackers can still correlate randomized MAC addresses with other probe request attributes, such as sequence numbers, information elements, or timing patterns, enabling device fingerprinting across networks.[91] [30] For instance, research from 2016 showed that Wi-Fi management frames retain sufficient stable data to defeat randomization in practice, undermining its core privacy goal.[91] Subsequent analyses in 2019 confirmed persistent vulnerabilities, including the "No-at-All" attack exploiting unrandomized elements in beacon frames.[92] A primary trade-off involves network usability and reliability, as randomization disrupts systems dependent on static MAC addresses for authentication and policy enforcement. In enterprise environments, mobile device management tools fail to consistently identify or provision devices, leading to recognition errors and communication breakdowns during address changes.[93] Home networks face similar issues, where features like parental controls, whitelisting, or bandwidth allocation break, requiring manual reconfiguration or disabling randomization per network.[73] Frequent regenerations—often per connection or daily—can trigger repeated authentication attempts, increasing latency, failed logins, and service interruptions, particularly in captive portals or enterprise Wi-Fi.[94] Randomization also complicates network diagnostics, analytics, and optimization. Service providers report challenges in device identification for troubleshooting or QoS enforcement, resulting in fragmented usage data and suboptimal performance allocation.[95] [73] While collision risks from randomized addresses remain low in typical deployments (e.g., probability below 0.1% in networks under 1,000 devices), they introduce minor overhead in dense environments.[96] Overall, these drawbacks pit privacy gains against operational stability, prompting recommendations for selective disabling in trusted networks or hybrid approaches combining randomization with higher-layer mitigations.[97]Notational and Implementation Conventions

Standard Hexadecimal Representations

The standard hexadecimal representation of a 48-bit MAC address (also known as MAC-48 or EUI-48) consists of twelve hexadecimal digits, divided into six pairs of two digits each, where each pair corresponds to one octet in canonical order. This format displays the octets from left to right without reversing the bits within each octet, reflecting the sequence as stored in memory or transmitted (with the least significant bit of each octet sent first on the wire, but hex conversion preserving standard binary ordering). Hexadecimal digits range from 0-9 and A-F (case-insensitive, though uppercase is conventional in most documentation).[8][7] In IEEE 802 documentation, hyphens (-) serve as the separator for this canonical hexadecimal notation, yielding formats likeAC-DE-48-00-00-02. This distinguishes it from bit-reversed variants, ensuring clarity in technical specifications. For instance, the IEEE Registration Authority assigns Organizationally Unique Identifiers (OUIs) in this hyphenated canonical form, with the first three octets typically representing the OUI followed by three octets for the device-specific portion.[8][6]

Although IEEE reserves colons (:) for bit-reversed representations (e.g., reversing bits per octet before hex conversion), colons are commonly adopted in practice for canonical addresses across networking tools, operating systems, and IETF documents, such as ac:de:48:00:00:02. This widespread use stems from readability preferences in software like Wireshark or ifconfig outputs, despite deviating from strict IEEE separator conventions for reversal indication. Both separators maintain the same underlying 48-bit value, serving solely for human parsing; unambiguous parsing requires context or validation against known OUIs.[8][98]

Bit-Reversed and Other Notations

The bit-reversed notation, also known as non-canonical or Token Ring format, represents each octet of a MAC address by reversing the order of its eight bits before converting the result to hexadecimal digits.[99][98] For example, the octet 0x1A (binary 00011010) becomes 0x58 (binary 01011000) after bit reversal, transforming a standard MAC address like 1A:2B:3C:4D:5E:6F into 58:D4:3C:B2:7A:F6.[99] This format arose due to differences in bit transmission order: Ethernet sends bits least-significant-bit (LSB) first within each octet, while Token Ring networks transmit most-significant-bit (MSB) first, necessitating bit reversal for consistent display or compatibility in mixed environments.[100][98] It is now rarely used outside legacy systems, as IEEE 802 standards favor the canonical format aligned with Ethernet's transmission order.[8] In the canonical (standard) notation, MAC addresses are displayed as six pairs of hexadecimal digits separated by colons (e.g., aa:bb:cc:dd:ee:ff) or hyphens (e.g., aa-bb-cc-dd-ee-ff), reflecting the octet values in the order of transmission bytes, with hex digits typically in lowercase or uppercase indifferently.[8][101] Alternative separators include periods in Cisco IOS displays, grouping every four bits (e.g., aabb.ccdd.eeff) for readability in command-line interfaces, though this is non-standard for general use.[102] Unseparated hexadecimal strings (e.g., aabbccddeeff) or decimal representations are occasionally employed in programming or databases but lack standardization and can lead to parsing errors.[101] The IEEE recommends colon-separated canonical form to avoid ambiguity, particularly when distinguishing bit order in protocols like IEEE 802.[8]Practical Implementations Across Devices

In network interface controllers (NICs) for personal computers and servers, MAC addresses are embedded in hardware during manufacturing, typically stored in ROM or EEPROM on Ethernet controllers compliant with IEEE 802.3 standards, enabling source and destination addressing in Ethernet frames for local area network communication.[38] Manufacturers obtain blocks of addresses from the IEEE Registration Authority, where the first 24 bits form the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI), and the remaining 24 bits are uniquely assigned by the vendor to each NIC.[103] Wireless devices, including WiFi adapters in laptops and integrated modules in smartphones, implement MAC addresses similarly in their chipsets for IEEE 802.11 protocol operations, such as association requests and frame acknowledgments; for instance, baseband processors in devices like Qualcomm or Broadcom WiFi chips use the hardware MAC as the foundation for link-layer identification.[38] In smartphones, operating systems like Android derive per-network randomized MAC addresses from this base hardware identifier to mitigate tracking, but the underlying silicon-level implementation remains fixed and manufacturer-assigned.[80]Routers and switches allocate unique MAC addresses to each physical or virtual interface from vendor-assigned blocks, facilitating layer-2 forwarding and ARP resolution; Cisco devices, for example, derive interface MACs sequentially from a base address burned into the system, with one address per Ethernet port plus additional for management functions.[104] This ensures distinct identification in bridged or switched domains, as required by IEEE 802.1 bridging standards.[105] In IoT devices, MAC addresses are integrated into microcontroller chips for wireless connectivity, such as in Espressif ESP32 modules where the 48-bit address is fused into the eFuse memory during fabrication, allowing retrieval via APIs for WiFi or Bluetooth provisioning while supporting local modifications for testing.[38] These implementations prioritize low-power operation, with the MAC enabling direct device-to-device or access point communication in standards like IEEE 802.15.4 for certain sensor networks.[106] Across all device types, the second least significant bit of the first octet distinguishes universally administered (factory-set) from locally administered addresses, allowing network operators to override defaults for redundancy or virtualization.[4]