Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ethernet

View on Wikipedia

Ethernet (/ˈiːθərnɛt/ EE-thər-net) is a family of wired computer networking technologies commonly used in local area networks (LAN), metropolitan area networks (MAN) and wide area networks (WAN).[1] It was commercially introduced in 1980 and first standardized in 1983 as IEEE 802.3. Ethernet has since been refined to support higher bit rates, a greater number of nodes, and longer link distances, but retains much backward compatibility. Over time, Ethernet has largely replaced competing wired LAN technologies such as Token Ring, FDDI and ARCNET.

The original 10BASE5 Ethernet uses a thick coaxial cable as a shared medium. This was largely superseded by 10BASE2, which used a thinner and more flexible cable that was both less expensive and easier to use. More modern Ethernet variants use twisted pair and fiber optic links in conjunction with switches. Over the course of its history, Ethernet data transfer rates have been increased from the original 2.94 Mbit/s[2] to the latest 800 Gbit/s, with rates up to 1.6 Tbit/s under development. The Ethernet standards include several wiring and signaling variants of the OSI physical layer.

Systems communicating over Ethernet divide a stream of data into shorter pieces called frames. Each frame contains source and destination addresses, and error-checking data so that damaged frames can be detected and discarded; most often, higher-layer protocols trigger retransmission of lost frames. Per the OSI model, Ethernet provides services up to and including the data link layer.[3] The 48-bit MAC address was adopted by other IEEE 802 networking standards, including IEEE 802.11 (Wi-Fi), as well as by FDDI. EtherType values are also used in Subnetwork Access Protocol (SNAP) headers. Ethernet uses serial communication in its PHY.

Ethernet is widely used in homes and industry, and interworks well with wireless Wi-Fi technologies. The Internet Protocol is commonly carried over Ethernet and so it is considered one of the key technologies that make up the Internet.

History

[edit]

Ethernet was developed at Xerox PARC between 1973 and 1974[4][5] as a means to allow Alto computers to communicate with each other.[6] It was inspired by ALOHAnet, which Robert Metcalfe had studied as part of his PhD dissertation[7][8] and was originally called the Alto Aloha Network.[6] Metcalfe's idea was essentially to limit the Aloha-like signals inside a cable, instead of broadcasting into the air. The idea was first documented in a memo that Metcalfe wrote on May 22, 1973, where he named it after the luminiferous aether once postulated to exist as an "omnipresent, completely passive medium for the propagation of electromagnetic waves."[4][9][10]

In 1975, Xerox filed a patent application listing Metcalfe, David Boggs, Chuck Thacker, and Butler Lampson as inventors.[11] In 1976, after the system was deployed at PARC, Metcalfe and Boggs published a seminal paper.[12][a] Ron Crane, Yogen Dalal,[14] Robert Garner, Hal Murray, Roy Ogus, Dave Redell and John Shoch facilitated the upgrade from the original 2.94 Mbit/s protocol to the 10 Mbit/s protocol, which was released to the market in 1980.[15]

Metcalfe left Xerox in June 1979 to form 3Com.[4][16] He convinced Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), Intel, and Xerox to work together to promote Ethernet as a standard. As part of that process Xerox agreed to relinquish their 'Ethernet' trademark.[17] The first standard was published on September 30, 1980, as "The Ethernet, A Local Area Network. Data Link Layer and Physical Layer Specifications".[18] This so-called DIX standard (Digital Intel Xerox)[19] specified 10 Mbit/s Ethernet, with 48-bit destination and source addresses and a global 16-bit Ethertype-type field.[20] Version 2 was published in November 1982[21] and defines what has become known as Ethernet II. Formal standardization efforts proceeded at the same time and resulted in the publication of IEEE 802.3 on June 23, 1983.[22]

Ethernet initially competed with Token Ring and other proprietary protocols. Ethernet was able to adapt to market needs, and with 10BASE2 shift to inexpensive thin coaxial cable, and from 1990 to the now-ubiquitous twisted pair with 10BASE-T. By the end of the 1980s, Ethernet was clearly the dominant network technology.[4] In the process, 3Com became a major company. 3Com shipped its first 10 Mbit/s Ethernet 3C100 NIC in March 1981, and that year started selling adapters for PDP-11s and VAXes, as well as Multibus-based Intel and Sun Microsystems computers.[23]: 9 This was followed quickly by DEC's Unibus to Ethernet adapter, which DEC sold and used internally to build its own corporate network, which reached over 10,000 nodes by 1986, making it one of the largest computer networks in the world at that time.[24] An Ethernet adapter card for the IBM PC was released in 1982, and, by 1985, 3Com had sold 100,000.[16] In the 1980s, IBM's own PC Network product competed with Ethernet for the PC, and through the 1980s, LAN hardware, in general, was not common on PCs. However, in the mid to late 1980s, PC networking did become popular in offices and schools for printer and fileserver sharing, and among the many diverse competing LAN technologies of that decade, Ethernet was one of the most popular. Parallel port based Ethernet adapters were produced for a time, with drivers for DOS and Windows. By the early 1990s, Ethernet became so prevalent that Ethernet ports began to appear on some PCs and most workstations. This process was greatly sped up with the introduction of 10BASE-T and its relatively small modular connector, at which point Ethernet ports appeared even on low-end motherboards.[citation needed]

Since then, Ethernet technology has evolved to meet new bandwidth and market requirements.[25] In addition to computers, Ethernet is now used to interconnect appliances and other personal devices.[4] As Industrial Ethernet it is used in industrial applications and is quickly replacing legacy data transmission systems in the world's telecommunications networks.[26] By 2010, the market for Ethernet equipment amounted to over $16 billion per year.[27]

Standardization

[edit]

In February 1980, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) started project 802 to standardize local area networks (LAN).[16][28] The DIX group with Gary Robinson (DEC), Phil Arst (Intel), and Bob Printis (Xerox) submitted the so-called Blue Book CSMA/CD specification as a candidate for the LAN specification.[20] In addition to CSMA/CD, Token Ring (supported by IBM) and Token Bus (selected and henceforward supported by General Motors) were also considered as candidates for a LAN standard. Competing proposals and broad interest in the initiative led to strong disagreement over which technology to standardize. In December 1980, the group was split into three subgroups, and standardization proceeded separately for each proposal.[16]

Delays in the standards process put at risk the market introduction of the Xerox Star workstation and 3Com's Ethernet LAN products. With such business implications in mind, David Liddle (General Manager, Xerox Office Systems) and Metcalfe (3Com) strongly supported a proposal of Fritz Röscheisen (Siemens Private Networks) for an alliance in the emerging office communication market, including Siemens' support for the international standardization of Ethernet (April 10, 1981). Ingrid Fromm, Siemens' representative to IEEE 802, quickly achieved broader support for Ethernet beyond IEEE by the establishment of a competing Task Group "Local Networks" within the European standards body ECMA TC24. In March 1982, ECMA TC24 with its corporate members reached an agreement on a standard for CSMA/CD based on the IEEE 802 draft.[23]: 8 Because the DIX proposal was most technically complete and because of the speedy action taken by ECMA which decisively contributed to the conciliation of opinions within IEEE, the IEEE 802.3 CSMA/CD standard was approved in December 1982.[16] IEEE published the 802.3 standard as a draft in 1983 and as a standard in 1985.[29]

Approval of Ethernet on the international level was achieved by a similar, cross-partisan action with Fromm as the liaison officer working to integrate with International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) Technical Committee 83 and International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Technical Committee 97 Sub Committee 6. The ISO 8802-3 standard was published in 1989.[30]

Evolution

[edit]Ethernet has evolved to include higher bandwidth, improved medium access control methods, and different physical media. The multidrop coaxial cable was replaced with physical point-to-point links connected by Ethernet repeaters or switches.[31]

Ethernet stations communicate by sending each other data packets: blocks of data individually sent and delivered. As with other IEEE 802 LANs, adapters come programmed with globally unique 48-bit MAC address so that each Ethernet station has a unique address.[b] The MAC addresses are used to specify both the destination and the source of each data packet. Ethernet establishes link-level connections, which can be defined using both the destination and source addresses. On reception of a transmission, the receiver uses the destination address to determine whether the transmission is relevant to the station or should be ignored. A network interface normally does not accept packets addressed to other Ethernet stations.[c][d]

An EtherType field in each frame is used by the operating system on the receiving station to select the appropriate protocol module (e.g., an Internet Protocol version such as IPv4). Ethernet frames are said to be self-identifying, because of the EtherType field. Self-identifying frames make it possible to intermix multiple protocols on the same physical network and allow a single computer to use multiple protocols together.[32] Despite the evolution of Ethernet technology, all generations of Ethernet (excluding early experimental versions) use the same frame formats.[33] Mixed-speed networks can be built using Ethernet switches and repeaters supporting the desired Ethernet variants.[34]

Due to the ubiquity of Ethernet, and the ever-decreasing cost of the hardware needed to support it, by 2004 most manufacturers built Ethernet interfaces directly into PC motherboards, eliminating the need for a separate network card.[35]

Shared medium

[edit]

Ethernet was originally based on the idea of computers communicating over a shared coaxial cable acting as a broadcast transmission medium. The method used was similar to those used in radio systems,[e] with the common cable providing the communication channel likened to the Luminiferous aether in 19th-century physics, and it was from this reference that the name Ethernet was derived.[36]

Original Ethernet's shared coaxial cable (the shared medium) traversed a building or campus to every attached machine. A scheme known as carrier-sense multiple access with collision detection (CSMA/CD) governed the way the computers shared the channel. This scheme was simpler than competing Token Ring or Token Bus technologies.[f] Computers are connected to an Attachment Unit Interface (AUI) transceiver, which is in turn connected to the cable (with thin Ethernet the transceiver is usually integrated into the network adapter). While a simple passive wire is highly reliable for small networks, it is not reliable for large extended networks, where damage to the wire in a single place, or a single bad connector, can make the whole Ethernet segment unusable.[g]

Through the first half of the 1980s, Ethernet's 10BASE5 implementation used a coaxial cable 0.375 inches (9.5 mm) in diameter, later called thick Ethernet or thicknet. Its successor, 10BASE2, called thin Ethernet or thinnet, used the RG-58 coaxial cable. The emphasis was on making installation of the cable easier and less costly.[37]: 57

Since all communication happens on the same wire, any information sent by one computer is received by all, even if that information is intended for just one destination.[h] The network interface card interrupts the CPU only when applicable packets are received: the card ignores information not addressed to it.[c] Use of a single cable also means that the data bandwidth is shared, such that, for example, available data bandwidth to each device is halved when two stations are simultaneously active.[38]

A collision happens when two stations attempt to transmit at the same time. They corrupt transmitted data and require stations to re-transmit. The lost data and re-transmission reduces throughput. In the worst case, where multiple active hosts connected with maximum allowed cable length attempt to transmit many short frames, excessive collisions can reduce throughput dramatically. However, a Xerox report in 1980 studied performance of an existing Ethernet installation under both normal and artificially generated heavy load. The report claimed that 98% throughput on the LAN was observed.[39] This is in contrast with token passing LANs (Token Ring, Token Bus), all of which suffer throughput degradation as each new node comes into the LAN, due to token waits. This report was controversial, as modeling showed that collision-based networks theoretically became unstable under loads as low as 37% of nominal capacity. Many early researchers failed to understand these results. Performance on real networks is significantly better.[40]

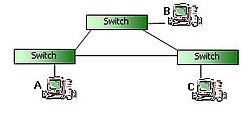

In a modern Ethernet, the stations do not all share one channel through a shared cable or a simple repeater hub; instead, each station communicates with a switch, which in turn forwards that traffic to the destination station. In this topology, collisions are only possible if station and switch attempt to communicate with each other at the same time, and collisions are limited to this link. Furthermore, the 10BASE-T standard introduced a full duplex mode of operation which became common with Fast Ethernet and the de facto standard with Gigabit Ethernet. In full duplex, switch and station can send and receive simultaneously, and therefore modern Ethernets are completely collision-free.

- Comparison between original Ethernet and modern Ethernet

-

The original Ethernet implementation: shared medium, collision-prone. All computers trying to communicate share the same cable, and so compete with each other.

-

Modern Ethernet implementation: switched connection, collision-free. Each computer communicates only with its own switch, without competition for the cable with others.

Repeaters and hubs

[edit]

For signal degradation and timing reasons, coaxial Ethernet segments have a restricted size.[41] Somewhat larger networks can be built by using an Ethernet repeater. Early repeaters had only two ports, allowing, at most, a doubling of network size. Once repeaters with more than two ports became available, it was possible to wire the network in a star topology. Early experiments with star topologies (called Fibernet) using optical fiber were published by 1978.[42]

Shared cable Ethernet is always hard to install in offices because its bus topology is in conflict with the star topology cable plans designed into buildings for telephony. Modifying Ethernet to conform to twisted-pair telephone wiring already installed in commercial buildings provided another opportunity to lower costs, expand the installed base, and leverage building design, and, thus, twisted-pair Ethernet was the next logical development in the mid-1980s.

Ethernet on unshielded twisted-pair cables (UTP) began with StarLAN at 1 Mbit/s in the mid-1980s.[citation needed] In 1987 SynOptics introduced the first twisted-pair Ethernet at 10 Mbit/s in a star-wired cabling topology with a central hub, later called LattisNet.[16][36]: 29 [43] These evolved into 10BASE-T, which was designed for point-to-point links only, and all termination was built into the device. This changed repeaters from a specialist device used at the center of large networks to a device that every twisted pair-based network with more than two machines had to use. The tree structure that resulted from this made Ethernet networks easier to maintain by preventing most faults with one peer or its associated cable from affecting other devices on the network.[citation needed]

Despite the physical star topology and the presence of separate transmit and receive channels in the twisted pair and fiber media, repeater-based Ethernet networks still use half-duplex and CSMA/CD, with only minimal activity by the repeater, primarily generation of the jam signal in dealing with packet collisions. Every packet is sent to every other port on the repeater, so bandwidth and security problems are not addressed. The total throughput of the repeater is limited to that of a single link, and all links must operate at the same speed.[36]: 278

Bridging and switching

[edit]

While repeaters can isolate some aspects of Ethernet segments, such as cable breakages, they still forward all traffic to all Ethernet devices. The entire network is one collision domain, and all hosts have to be able to detect collisions anywhere on the network. This limits the number of repeaters between the farthest nodes and creates practical limits on how many machines can communicate on an Ethernet network. Segments joined by repeaters have to all operate at the same speed, making phased-in upgrades impossible.[citation needed]

To alleviate these problems, bridging was created to communicate at the data link layer while isolating the physical layer. With bridging, only well-formed Ethernet packets are forwarded from one Ethernet segment to another; collisions and packet errors are isolated. At initial startup, Ethernet bridges work somewhat like Ethernet repeaters, passing all traffic between segments. By observing the source addresses of incoming frames, the bridge then builds an address table associating addresses to segments. Once an address is learned, the bridge forwards network traffic destined for that address only to the associated segment, improving overall performance. Broadcast traffic is still forwarded to all network segments. Bridges also overcome the limits on total segments between two hosts and allow the mixing of speeds, both of which are critical to the incremental deployment of faster Ethernet variants.[citation needed]

In 1989, Motorola Codex introduced their 6310 EtherSpan, and Kalpana introduced their EtherSwitch; these were examples of the first commercial Ethernet switches.[i] Early switches such as this used cut-through switching where only the header of the incoming packet is examined before it is either dropped or forwarded to another segment.[44] This reduces the forwarding latency. One drawback of this method is that it does not readily allow a mixture of different link speeds. Another is that packets that have been corrupted are still propagated through the network. The eventual remedy for this was a return to the original store and forward approach of bridging, where the packet is read into a buffer on the switch in its entirety, its frame check sequence verified and only then the packet is forwarded.[44] In modern network equipment, this process is typically done using application-specific integrated circuits allowing packets to be forwarded at wire speed.[citation needed]

When a twisted pair or fiber link segment is used and neither end is connected to a repeater, full-duplex Ethernet becomes possible over that segment. In full-duplex mode, both devices can transmit and receive to and from each other at the same time, and there is no collision domain.[45] This doubles the aggregate bandwidth of the link and is sometimes advertised as double the link speed (for example, 200 Mbit/s for Fast Ethernet).[j] The elimination of the collision domain for these connections also means that all the link's bandwidth can be used by the two devices on that segment and that segment length is not limited by the constraints of collision detection.

Since packets are typically delivered only to the port they are intended for, traffic on a switched Ethernet is less public than on shared-medium Ethernet. Despite this, switched Ethernet should still be regarded as an insecure network technology, because it is easy to subvert switched Ethernet systems by means such as ARP spoofing and MAC flooding.[citation needed][46]

The bandwidth advantages, the improved isolation of devices from each other, the ability to easily mix different speeds of devices and the elimination of the chaining limits inherent in non-switched Ethernet have made switched Ethernet the dominant network technology.[47]

Advanced networking

[edit]

Simple switched Ethernet networks, while a great improvement over repeater-based Ethernet, suffer from single points of failure, attacks that trick switches or hosts into sending data to a machine even if it is not intended for it, scalability and security issues with regard to switching loops, broadcast radiation, and multicast traffic.[citation needed]

Advanced networking features in switches use Shortest Path Bridging (SPB) or the Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) to maintain a loop-free, meshed network, allowing physical loops for redundancy (STP) or load-balancing (SPB). Shortest Path Bridging includes the use of the link-state routing protocol IS-IS to allow larger networks with shortest path routes between devices.

Advanced networking features also ensure port security, provide protection features such as MAC lockdown[48] and broadcast radiation filtering, use VLANs to keep different classes of users separate while using the same physical infrastructure,[49] and use link aggregation to add bandwidth to overloaded links and to provide some redundancy.[50]

In 2016, Ethernet replaced InfiniBand as the most popular system interconnect of TOP500 supercomputers.[51]

Varieties

[edit]

The Ethernet physical layer evolved over a considerable time span and encompasses coaxial, twisted pair and fiber-optic physical media interfaces, with speeds from 1 Mbit/s to 400 Gbit/s.[52] The first introduction of twisted-pair CSMA/CD was StarLAN, standardized as 802.3 1BASE5.[53] While 1BASE5 had little market penetration, it defined the physical apparatus (wire, plug/jack, pin-out, and wiring plan) that would be carried over to 10BASE-T through 10GBASE-T.

The most common forms used are 10BASE-T, 100BASE-TX, and 1000BASE-T. All three use twisted-pair cables and 8P8C modular connectors. They run at 10 Mbit/s, 100 Mbit/s, and 1 Gbit/s, respectively.[54][55][56]

Fiber optic variants of Ethernet (that commonly use SFP modules) are also very popular in larger networks, offering high performance, better electrical isolation and longer distance (tens of kilometers with some versions). In general, network protocol stack software will work similarly on all varieties.[57]

Frame structure

[edit]

In IEEE 802.3, a datagram is called a packet or frame. Packet is used to describe the overall transmission unit and includes the preamble, start frame delimiter (SFD) and carrier extension (if present).[k] The frame begins after the start frame delimiter with a frame header featuring source and destination MAC addresses and the EtherType field giving either the protocol type for the payload protocol or the length of the payload. The middle section of the frame consists of payload data including any headers for other protocols (for example, Internet Protocol) carried in the frame. The frame ends with a 32-bit cyclic redundancy check, which is used to detect corruption of data in transit.[58]: sections 3.1.1 and 3.2 Notably, Ethernet packets have no time-to-live field, leading to possible problems in the presence of a switching loop.

Autonegotiation

[edit]Autonegotiation is the procedure by which two connected devices choose common transmission parameters, e.g. speed and duplex mode. Autonegotiation was initially an optional feature, first introduced with 100BASE-TX (1995 IEEE 802.3u Fast Ethernet standard), and is backward compatible with 10BASE-T. The specification was improved in the 1998 release of IEEE 802.3. Autonegotiation is mandatory for 1000BASE-T and faster.

Error conditions

[edit]Switching loop

[edit]A switching loop or bridge loop occurs in computer networks when there is more than one Layer 2 (OSI model) path between two endpoints (e.g. multiple connections between two network switches or two ports on the same switch connected to each other). The loop creates broadcast storms as broadcasts and multicasts are forwarded by switches out every port, the switch or switches will repeatedly rebroadcast the broadcast messages flooding the network. Since the Layer 2 header does not support a time to live (TTL) value, if a frame is sent into a looped topology, it can loop forever.[59]

A physical topology that contains switching or bridge loops is attractive for redundancy reasons, yet a switched network must not have loops. The solution is to allow physical loops, but create a loop-free logical topology using the SPB protocol or the older STP on the network switches.[citation needed]

Jabber

[edit]A node that is sending longer than the maximum transmission window for an Ethernet packet is considered to be jabbering. Depending on the physical topology, jabber detection and remedy differ somewhat.

- An MAU is required to detect and stop abnormally long transmission from the DTE (longer than 20–150 ms) in order to prevent permanent network disruption.[60]

- On an electrically shared medium (10BASE5, 10BASE2, 1BASE5), jabber can only be detected by each end node, stopping reception. No further remedy is possible.[61]

- A repeater/repeater hub uses a jabber timer that ends retransmission to the other ports when it expires. The timer runs for 25,000 to 50,000 bit times for 1 Mbit/s,[62] 40,000 to 75,000 bit times for 10 and 100 Mbit/s,[63][64] and 80,000 to 150,000 bit times for 1 Gbit/s.[65] Jabbering ports are partitioned off the network until a carrier is no longer detected.[66]

- End nodes utilizing a MAC layer will usually detect an oversized Ethernet frame and cease receiving. A bridge/switch will not forward the frame.[67]

- A non-uniform frame size configuration in the network using jumbo frames may be detected as jabber by end nodes.[citation needed] Jumbo frames are not part of the official IEEE 802.3 Ethernet standard.

- A packet detected as jabber by an upstream repeater and subsequently cut off has an invalid frame check sequence and is dropped.[68]

Runt frames

[edit]See also

[edit]- 5-4-3 rule

- Chaosnet

- Ethernet Alliance

- Ethernet crossover cable

- Ethernet Technology Consortium

- Fiber media converter

- ISO/IEC 11801

- Link Layer Discovery Protocol

- List of interface bit rates

- LocalTalk

- PHY

- Physical coding sublayer

- Power over Ethernet

- Point-to-Point Protocol over Ethernet (PPPoE)

- Sneakernet

- Wake-on-LAN (WoL)

Notes

[edit]- ^ The experimental Ethernet described in the 1976 paper ran at 2.94 Mbit/s and has eight-bit destination and source address fields, so the original Ethernet addresses are not the MAC addresses they are today.[13] By software convention, the 16 bits after the destination and source address fields specify a "packet type", but, as the paper says, "different protocols use disjoint sets of packet types". Thus the original packet types could vary within each different protocol. This is in contrast to the EtherType in the IEEE Ethernet standard, which specifies the protocol being used.

- ^ In some cases, the factory-assigned address can be overridden, either to avoid an address change when an adapter is replaced or to use locally administered addresses.

- ^ a b Unless it is put into promiscuous mode.

- ^ Of course bridges and switches will accept other addresses for forwarding the packet.

- ^ There are fundamental differences between wireless and wired shared-medium communication, such as the fact that it is much easier to detect collisions in a wired system than a wireless system.

- ^ In a CSMA/CD system packets must be large enough to guarantee that the leading edge of the propagating wave of a message gets to all parts of the medium and back again before the transmitter stops transmitting, guaranteeing that collisions (two or more packets initiated within a window of time that forced them to overlap) are discovered. As a result, the minimum packet size and the physical medium's total length are closely linked.

- ^ Multipoint systems are also prone to strange failure modes when an electrical discontinuity reflects the signal in such a manner that some nodes would work properly, while others work slowly because of excessive retries or not at all. See standing wave for an explanation. These could be much more difficult to diagnose than a complete failure of the segment.

- ^ This one speaks, all listen property is a security weakness of shared-medium Ethernet, since a node on an Ethernet network can eavesdrop on all traffic on the wire if it so chooses.

- ^ The term switch was invented by device manufacturers and does not appear in the IEEE 802.3 standard.

- ^ This is misleading, as performance will double only if traffic patterns are symmetrical.

- ^ The carrier extension is defined to assist collision detection on shared-media gigabit Ethernet.

References

[edit]- ^ Ralph Santitoro (2003). "Metro Ethernet Services – A Technical Overview" (PDF). mef.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Xerox (August 1976). "Alto: A Personal Computer System Hardware Manual" (PDF). Xerox. p. 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Charles M. Kozierok (September 20, 2005). "Data Link Layer (Layer 2)". tcpipguide.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e The History of Ethernet. NetEvents.tv. 2006. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Ethernet Prototype Circuit Board". Smithsonian National Museum of American History. 1973. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- ^ a b Joanna Goodrich (November 16, 2023). "Ethernet is Still Going Strong After 50 Years". IEEE Spectrum.

- ^ Gerald W. Brock (September 25, 2003). The Second Information Revolution. Harvard University Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-674-01178-3.

- ^ Metz, Cade (March 22, 2023). "Turing Award Won by Co-Inventor of Ethernet Technology". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 23, 2023. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ Cade Metz (March 13, 2009). "Ethernet – a

networking protocolname for the ages: Michelson, Morley, and Metcalfe". The Register. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2013. - ^ Mary Bellis. "Inventors of the Modern Computer". About.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ U.S. patent 4,063,220 "Multipoint data communication system (with collision detection)"

- ^ Robert Metcalfe; David Boggs (July 1976). "Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 19 (7): 395–405. doi:10.1145/360248.360253. S2CID 429216. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ John F. Shoch; Yogen K. Dalal; David D. Redell; Ronald C. Crane (August 1982). "Evolution of the Ethernet Local Computer Network" (PDF). IEEE Computer. 15 (8): 14–26. Bibcode:1982Compr..15h..10S. doi:10.1109/MC.1982.1654107. S2CID 14546631. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ Pelkey, James L. (2007). "Yogen Dalal". Entrepreneurial Capitalism and Innovation: A History of Computer Communications, 1968–1988. Archived from the original on September 5, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "Introduction to Ethernet Technologies". www.wband.com. WideBand Products. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f von Burg, Urs; Kenney, Martin (December 2003). "Sponsors, Communities, and Standards: Ethernet vs. Token Ring in the Local Area Networking Business" (PDF). Industry & Innovation. 10 (4): 351–375. doi:10.1080/1366271032000163621. S2CID 153804163. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 6, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ Charles E. Spurgeon (2000). "Chapter 1. The Evolution of Ethernet". Ethernet: The Definitive Guide. ISBN 1565926609. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "The ethernet: a local area network: data link layer and physical layer specifications". ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review. 11 (3): 20–66. July 1981. doi:10.1145/1015591.1015594.

- ^ "Ethernet: Bridging the communications gap". Hardcopy. March 1981. p. 12.

- ^ a b Digital Equipment Corporation; Intel Corporation; Xerox Corporation (September 30, 1980). "The Ethernet, A Local Area Network. Data Link Layer and Physical Layer Specifications, Version 1.0" (PDF). Xerox Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 25, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Digital Equipment Corporation; Intel Corporation; Xerox Corporation (November 1982). "The Ethernet, A Local Area Network. Data Link Layer and Physical Layer Specifications, Version 2.0" (PDF). Xerox Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 15, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "IEEE 802.3 'Standard for Ethernet' Marks 30 Years of Innovation and Global Market Growth" (Press release). IEEE. June 24, 2013. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ a b Robert Breyer; Sean Riley (1999). Switched, Fast, and Gigabit Ethernet. Macmillan. ISBN 1-57870-073-6.

- ^ Jamie Parker Pearson (1992). Digital at Work. Digital Press. p. 163. ISBN 1-55558-092-0.

- ^ Rick Merritt (December 20, 2010). "Shifts, growth ahead for 10G Ethernet". E Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "My oh My – Ethernet Growth Continues to Soar; Surpasses Legacy". Telecom News Now. July 29, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Jim Duffy (February 22, 2010). "Cisco, Juniper, HP drive Ethernet switch market in Q4". Network World. International Data Group. Archived from the original on August 11, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^ Vic Hayes (August 27, 2001). "Letter to FCC" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

IEEE 802 has the basic charter to develop and maintain networking standards... IEEE 802 was formed in February 1980...

- ^ IEEE 802.3-2008, p.iv

- ^ "ISO 8802-3:1989". ISO. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Jim Duffy (April 20, 2009). "Evolution of Ethernet". Network World. Archived from the original on June 11, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ Douglas E. Comer (2000). Internetworking with TCP/IP – Principles, Protocols and Architecture (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-018380-6. 2.4.9 – Ethernet Hardware Addresses, p. 29, explains the filtering.

- ^ Iljitsch van Beijnum (July 15, 2011). "Speed matters: how Ethernet went from 3Mbps to 100Gbps... and beyond". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

All aspects of Ethernet were changed: its MAC procedure, the bit encoding, the wiring... only the packet format has remained the same.

- ^ Fast Ethernet Turtorial, Lantronix, December 9, 2014, archived from the original on November 28, 2015, retrieved January 1, 2016

- ^ Geetaj Channana (November 1, 2004). "Motherboard Chipsets Roundup". PCQuest. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

While comparing motherboards in the last issue we found that all motherboards support Ethernet connection on board.

- ^ a b c Charles E. Spurgeon (2000). Ethernet: The Definitive Guide. O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-56592-660-8.

- ^ Heinz-Gerd Hegering; Alfred Lapple (1993). Ethernet: Building a Communications Infrastructure. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-62405-2.

- ^ Ethernet Tutorial – Part I: Networking Basics, Lantronix, December 9, 2014, archived from the original on February 13, 2016, retrieved January 1, 2016

- ^ Shoch, John F.; Hupp, Jon A. (December 1980). "Measured performance of an Ethernet local network". Communications of the ACM. 23 (12). ACM Press: 711–721. doi:10.1145/359038.359044. ISSN 0001-0782. S2CID 1002624.

- ^ Boggs, D.R.; Mogul, J.C. & Kent, C.A. (September 1988). "Measured capacity of an Ethernet: myths and reality" (PDF). DEC WRL. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Ethernet Media Standards and Distances". kb.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ Eric G. Rawson; Robert M. Metcalfe (July 1978). "Fibemet: Multimode Optical Fibers for Local Computer Networks" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Communications. 26 (7): 983–990. Bibcode:1978ITCom..26..983R. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1978.1094189. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ Urs von Burg (2001). The Triumph of Ethernet: technological communities and the battle for the LAN standard. Stanford University Press. p. 175. ISBN 0-8047-4094-1. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Robert J. Kohlhepp (October 2, 2000). "The 10 Most Important Products of the Decade". Network Computing. Archived from the original on January 5, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ Nick Pidgeon (April 2000). "Full-duplex Ethernet". How Stuff Works. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ Wang, Shuangbao Paul; Ledley, Robert S. (October 25, 2012). Computer Architecture and Security: Fundamentals of Designing Secure Computer Systems. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-16883-7. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ "Token Ring-to-Ethernet Migration". Cisco. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

Respondents were first asked about their current and planned desktop LAN attachment standards. The results were clear—switched Fast Ethernet is the dominant choice for desktop connectivity to the network

- ^ David Davis (October 11, 2007). "Lock down Cisco switch port security". Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "Virtual LANs (VLANS) | Department of Computer Science Computing Guide". csguide.cs.princeton.edu. Retrieved October 9, 2025.

- ^ Tholeti, Bhanu Prakash Reddy (2013). "Hypervisors, Virtualization, and Networking". Handbook of Fiber Optic Data Communication. pp. 387–416. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-401673-6.00016-7. ISBN 978-0-12-401673-6.

A link aggregation, or EtherChannel, device is a network port-aggregation technology that allows several Ethernet adapters to be aggregated. The adapters can then act as a single Ethernet device. Link aggregation helps to provide more throughput over a single IP address than would be possible with a single Ethernet adapter.

- ^ "HIGHLIGHTS – JUNE 2016". June 2016. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

InfiniBand technology is now found on 205 systems, down from 235 systems, and is now the second most-used internal system interconnect technology. Gigabit Ethernet has risen to 218 systems up from 182 systems, in large part thanks to 176 systems now using 10G interfaces.

- ^ "[STDS-802-3-400G] IEEE P802.3bs Approved!". IEEE 802.3bs Task Force. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ "1BASE5 Medium Specification (StarLAN)". cs.nthu.edu.tw. December 28, 1996. Archived from the original on July 10, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ IEEE 802.3 14. Twisted-pair medium attachment unit (MAU) and baseband medium, type 10BASE-T including type 10BASE-Te

- ^ IEEE 802.3 25. Physical Medium Dependent (PMD) sublayer and baseband medium, type 100BASE-TX

- ^ IEEE 802.3 40. Physical Coding Sublayer (PCS), Physical Medium Attachment (PMA) sublayer and baseband medium, type 1000BASE-T

- ^ IEEE 802.3 4.3 Interfaces to/from adjacent layers

- ^ "802.3-2012 – IEEE Standard for Ethernet". IEEE. IEEE Standards Association. December 28, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ "Layer 2 Switching Loops in Network Explained". ComputerNetworkingNotes. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ IEEE 802.3 8.2 MAU functional specifications

- ^ IEEE 802.3 8.2.1.5 Jabber function requirements

- ^ IEEE 802.3 12.4.3.2.3 Jabber function

- ^ IEEE 802.3 9.6.5 MAU Jabber Lockup Protection

- ^ IEEE 802.3 27.3.2.1.4 Timers

- ^ IEEE 802.3 41.2.2.1.4 Timers

- ^ IEEE 802.3 27.3.1.7 Receive jabber functional requirements

- ^ IEEE 802.1 Table C-1—Largest frame base values

- ^ "3.1.1 Packet format", 802.3-2012 - IEEE Standard for Ethernet (PDF), IEEE Standards Association, December 28, 2012, retrieved July 5, 2015

- ^ "Troubleshooting Ethernet". Cisco. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- "Ethernet Technologies". Internetworking Technology Handbook. Cisco Systems. Archived from the original on December 28, 2018. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- Charles E. Spurgeon (2000). Ethernet: The Definitive Guide. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1565-9266-08.

- Yogen Dalal. "Ethernet History". blog.

External links

[edit]Ethernet

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Invention and Early Prototypes

Ethernet originated at Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in 1973, where Robert Metcalfe, along with David Boggs and others, developed the concept as a means to interconnect the newly created Alto personal computers for resource sharing, such as printers and file servers.[2][4] The invention drew inspiration from the University of Hawaii's ALOHAnet, a wireless packet radio network operational since 1971 that demonstrated the feasibility of shared-medium communication, as well as the ARPANET's packet-switching principles.[4][5] On May 22, 1973, Metcalfe authored an internal memo titled "Alto Aloha Network," outlining the foundational idea of using coaxial cable to create a multipoint data communication system.[6] This marked the conceptual birth of Ethernet, named after the luminiferous ether as a metaphor for the pervasive medium carrying data packets.[7] The initial prototype, built by Metcalfe and Boggs in late 1973, operated at a data rate of 2.94 Mbps over thick coaxial cable, employing a carrier-sense multiple access with collision detection (CSMA/CD) protocol adapted from ALOHAnet's slotted ALOHA mechanism to manage shared access and resolve conflicts on the bus topology.[8][9] Early implementation faced significant challenges in collision detection, requiring precise timing to ensure stations could sense and abort transmissions within the network's propagation delay—estimated at about 2.5 microseconds per 500 meters of cable—to maintain efficiency and prevent data loss.[10] Cable specifications also posed hurdles, as the system demanded 50-ohm coaxial cable with controlled impedance to minimize signal reflections and attenuation, alongside transceivers capable of injecting and extracting signals without disrupting the bus.[11] Xerox filed the first patent for this multipoint system with collision detection on March 31, 1975 (U.S. Patent 4,063,220, granted in 1977), crediting Metcalfe, Boggs, Chuck Thacker, and Butler Lampson as co-inventors.[12] By 1976, the prototype had evolved into a functional network connecting over 100 Alto computers at PARC, demonstrated successfully in a lab setting to showcase reliable packet transmission and resource sharing, as detailed in the seminal paper "Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks" by Metcalfe and Boggs.[13][14] This demonstration validated the CSMA/CD approach, achieving low collision rates under moderate loads while addressing early issues like signal integrity over longer cable segments. In 1979, to promote broader adoption, Xerox collaborated with Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and Intel to form the DIX consortium, standardizing Ethernet at 10 Mbps using the same CSMA/CD method and coaxial medium, which laid the groundwork for commercial viability.[10]Commercialization and Widespread Adoption

The Digital Equipment Corporation, Intel, and Xerox (DIX) consortium played a pivotal role in commercializing Ethernet by publishing the first Ethernet specification, known as the "Blue Book," on September 30, 1980, which defined the 10BASE5 standard using thick coaxial cable for 10 Mbps operation.[15] This specification enabled the release of the first commercial Ethernet products later that year, including protocol software from 3Com Corporation, founded by Ethernet co-inventor Robert Metcalfe to promote the technology.[16] 3Com followed with its first hardware, the EtherLink network interface card, in 1982, marking the entry of Ethernet into the commercial market for local area networks (LANs).[17] In the early 1980s, Ethernet saw initial adoption primarily in universities and research laboratories, where it facilitated resource sharing among workstations and servers.[18] For instance, institutions like the University of California, Berkeley, integrated Ethernet support into UNIX-based systems through Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) releases, enabling TCP/IP networking over Ethernet in academic environments.[19] This early uptake in research settings demonstrated Ethernet's reliability for collaborative computing, paving the way for broader implementation. The ratification of the IEEE 802.3 standard in June 1983 provided a vendor-neutral framework based on the DIX specification, fostering interoperability and encouraging widespread vendor participation beyond the original consortium.[4] By the mid-1980s, Ethernet had begun to dominate the LAN market, surpassing competitors like Token Ring due to its cost-effectiveness and simplicity, with installations growing rapidly in corporate and institutional settings.[20] A key milestone came in 1985 with AT&T's introduction of StarLAN, the first Ethernet variant using unshielded twisted-pair (UTP) wiring at 1 Mbps in a star topology, which leveraged existing telephone cabling and reduced installation costs.[2] The 1990s witnessed an explosion in Ethernet adoption following the 1990 ratification of the IEEE 802.3i amendment for 10BASE-T, which standardized 10 Mbps over UTP with RJ-45 connectors, and the proliferation of affordable Ethernet hubs that simplified network expansion.[4] These developments made Ethernet accessible for desktop computing, driving its integration into personal computers and office environments. By 1998, Ethernet had captured approximately 85% of the global LAN market share, reflecting its evolution from a niche technology to the dominant standard for wired networking.[21]Standards and Specifications

IEEE 802.3 Standard

The IEEE 802 committee originated from Project 802, authorized by the IEEE Standards Board in October 1979 to establish standards for local area networks (LANs), sponsored by the Computer Society's Technical Committee on Computer Communications.[22] This initiative addressed the growing need for interoperable networking protocols amid competing proprietary systems. Within Project 802, the 802.3 working group was specifically assigned to develop standards for LANs using the Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Detection (CSMA/CD) access method, building on Ethernet's foundational principles.[2] The IEEE 802.3-1983 standard was ratified in June 1983, providing a formalized specification that closely mirrored the Digital-Intel-Xerox (DIX) Ethernet Version 1.0 from 1980 while introducing rigorous testing procedures and conformance criteria to ensure device interoperability.[2] This ratification marked Ethernet's transition from a vendor-specific protocol to an open industry standard, enabling broader adoption in commercial environments.[23] The standard encompassed the Physical Layer for media transmission, the MAC sublayer for access control, and a reconciliation mechanism mapping MAC signals to Physical Layer services, collectively defining the OSI Layers 1 and 2 for CSMA/CD networks.[24] Key specifications in IEEE 802.3-1983 included a nominal data rate of 10 Mbps over 10BASE5 coaxial cable, utilizing Manchester encoding for self-clocking signal transmission to maintain synchronization over shared media.[25] The frame structure incorporated a 7-byte preamble of alternating 1s and 0s for bit synchronization, followed by a 1-byte Start Frame Delimiter (SFD) to signal the frame's beginning, ensuring reliable detection amid potential noise.[26] In contrast to the DIX specification, IEEE 802.3-1983 introduced jabber protection in the MAC sublayer, which disables a station's transmitter after detecting continuous transmission exceeding 20,000 to 50,000 bit times (2 ms to 5 ms at 10 Mb/s) to prevent network disruption from malfunctioning devices.[24] Additionally, it defined a formal service interface to the IEEE 802.2 Logical Link Control (LLC) sublayer, replacing the DIX EtherType field with a length field and enabling protocol multiplexing through LLC headers for enhanced flexibility in upper-layer protocols.[27]Evolution of Standards and Amendments

The IEEE 802.3 Working Group develops amendments to the base Ethernet standard through a structured process initiated by a project authorization request (PAR) submitted to the IEEE Standards Association, outlining the scope, purpose, and technical needs. A task force is then formed to draft specifications, which undergo iterative reviews, including working group ballots for technical consensus and sponsor ballots for broader validation, before final approval by the IEEE Standards Board and publication as an amendment. These amendments are periodically consolidated into revised base standards to streamline the document; for example, IEEE Std 802.3-2018 incorporated over 30 prior amendments, creating a unified reference up to 400 Gb/s operations.[28] Early amendments focused on expanding media options and speeds beyond the original coaxial cable implementations. In 1990, IEEE Std 802.3i introduced 10BASE-T, enabling 10 Mb/s Ethernet over unshielded twisted-pair (UTP) cabling in a star topology, which facilitated widespread adoption in office environments due to its cost-effectiveness and ease of installation.[29] This was followed in 1995 by IEEE Std 802.3u, defining Fast Ethernet at 100 Mb/s with variants like 100BASE-TX over Category 5 UTP and 100BASE-FX over fiber, supporting full-duplex operation to double effective throughput without collisions. By 1999, IEEE Std 802.3ab specified 1000BASE-T for 1 Gb/s over existing Category 5 UTP using all four pairs with advanced encoding, marking a significant leap for enterprise networks while maintaining backward compatibility.[30] The progression to gigabit and higher speeds accelerated in the 2000s, addressing demands from data centers and backbone infrastructure. IEEE Std 802.3ae, ratified in 2002, established 10 Gigabit Ethernet with full-duplex physical layers for LAN (10GBASE-R) and WAN (10GBASE-W) applications over fiber up to 40 km, using wavelength-division multiplexing for scalability. In 2006, IEEE Std 802.3an extended this to 10GBASE-T over Category 6A UTP for distances up to 100 m, incorporating PAM-16 modulation and echo cancellation to enable copper-based 10 Gb/s in legacy cabling environments.[31] Later, IEEE Std 802.3bs in 2017 defined 200 Gb/s and 400 Gb/s Ethernet using 50 Gb/s lanes aggregated via 4-level pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM4), targeting high-density data center switches and supporting multimode and single-mode fiber. Recent amendments have emphasized power delivery, higher speeds, and real-time capabilities. IEEE Std 802.3bt, approved in 2018, enhanced Power over Ethernet (PoE) to deliver up to 90 W per port using all four twisted pairs (Type 3 and Type 4), enabling efficient powering of high-demand devices like pan-tilt-zoom cameras and access points while ensuring backward compatibility with earlier PoE standards.[32] For time-sensitive networking (TSN), amendments like IEEE Std 802.3br (2016) introduced interspersing express traffic (IET) and frame preemption, integrating with IEEE 802.1Qbv's time-aware shaping to provide low-latency, deterministic transmission for industrial and automotive applications by allowing high-priority frames to interrupt lower-priority ones. In 2024, IEEE Std 802.3df added support for 800 Gb/s Ethernet with MAC parameters and physical layers using eight 100 Gb/s or four 200 Gb/s lanes, optimized for short-reach copper and optical interconnects in AI-driven data centers. Looking ahead, the Ethernet Alliance's 2025 Roadmap projects advancements to 1.6 Tb/s speeds by the late 2020s, driven by AI and cloud computing requirements for massive parallelism and low-latency interconnects, with interim milestones including enhanced 800 Gb/s electrical interfaces and co-packaged optics to reduce power consumption and latency.[33]Physical and Data Link Layers

Physical Layer Technologies

The physical layer (PHY) of Ethernet, as defined in the IEEE 802.3 standard, is responsible for the transmission and reception of raw bit streams over physical media, encompassing bit encoding, scrambling for spectral shaping, and equalization to mitigate signal distortion.[34] Bit encoding schemes vary by speed: early 10 Mbps Ethernet (10BASE-T) uses Manchester encoding to ensure clock synchronization through mid-bit transitions, while Fast Ethernet (100 Mbps, 100BASE-TX) employs 4B/5B block coding to map 4 data bits into 5-bit symbols for DC balance and error detection, combined with NRZI (non-return-to-zero inverted) signaling.[35] For higher speeds like 10 Gbps and beyond, 64B/66B encoding is standard, converting 64 data bits into 66-bit blocks with a 2-bit sync header to maintain low overhead (about 3.125%) and support efficient forward error correction.[36] Scrambling, such as self-synchronizing scramblers in 1000BASE-T, randomizes the bit stream to avoid spectral peaks, and equalization techniques like decision-feedback equalizers compensate for inter-symbol interference in twisted-pair channels.[37] Ethernet PHY supports diverse media types to accommodate varying distances and bandwidth needs. Early implementations relied on coaxial cable, such as 10BASE5 (thick coax) for bus topologies up to 500 meters and 10BASE2 (thin coax) for shorter segments, but these have been largely supplanted by more flexible options.[38] Twisted-pair copper, particularly unshielded twisted-pair (UTP) categories like Cat5e and higher, dominates modern deployments for its cost-effectiveness and ease of installation, enabling speeds from 100 Mbps (100BASE-TX) to 10 Gbps (10GBASE-T) over distances up to 100 meters.[38] Fiber optic media, including multimode fiber (MMF) for shorter reaches (e.g., up to 550 meters at 10 Gbps) and single-mode fiber (SMF) for long-haul (up to 40 km or more), provide immunity to electromagnetic interference and support ultra-high speeds, using laser or LED sources.[38] Specific PHY technologies exemplify these principles. For Gigabit Ethernet over twisted pair (1000BASE-T), the standard uses four parallel pairs with PAM-5 (pulse-amplitude modulation with 5 levels) encoding at 125 MHz symbol rate per pair, achieving 1 Gbps aggregate while supporting full-duplex operation through echo cancellation and crosstalk mitigation via digital signal processing.[37] In optical variants, 10GBASE-SR employs short-range multimode fiber with 850 nm vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser (VCSEL) sources, transmitting at 10.3125 Gbps over up to 300 meters using 64B/66B encoding and OM3/OM4 fiber grades. Power over Ethernet (PoE) extends PHY capabilities by delivering DC power alongside data over twisted-pair cables, defined in IEEE 802.3 amendments. The original 802.3af (PoE) standard provides up to 15.4 W at the power sourcing equipment (PSE), with about 12.95 W available at the powered device (PD) after cable losses, using two pairs (Mode A or B).[39] Enhanced by 802.3at (PoE+), it raises power to 30 W at the PSE (25.5 W at PD), still on two pairs, supporting devices like pan-tilt-zoom cameras.[39] The 802.3bt (PoE++) standard, ratified in 2018, enables higher power using all four pairs: Type 3 up to 60 W at the PSE (51 W at PD) and Type 4 up to 90 W at the PSE (71.3 W at PD), facilitating high-power applications such as Wi-Fi 6 access points and LED lighting.[39] As of 2025, advancements in PHY technologies focus on terabit-scale Ethernet, with 400 Gbps and higher variants leveraging PAM4 (pulse-amplitude modulation with 4 levels) for electrical interfaces over twinaxial copper cables. PAM4 doubles the bit rate per symbol compared to NRZ by encoding two bits per level, enabling 400GBASE-CR4 over up to 2 meters of twinax with four 100 Gbps lanes, as outlined in the IEEE 802.3ck amendment and Ethernet Alliance roadmap.[40] These developments incorporate advanced forward error correction and retimers to maintain signal integrity at 106 Gbps per lane, supporting AI-driven data centers.[40]Media Access Control (MAC) Layer

The Media Access Control (MAC) sublayer of Ethernet, defined in IEEE 802.3, operates within the data link layer to provide core functions for frame encapsulation, addressing, and medium access control, enabling reliable data transfer over shared or dedicated links. It assembles higher-layer data into Ethernet frames by adding headers and trailers, including source and destination addresses, while ensuring frame integrity through a frame check sequence. In half-duplex environments, the MAC employs Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Detection (CSMA/CD) to manage contention on shared media, where stations listen to the medium before transmitting and detect collisions during transmission.[28][41] Under CSMA/CD, a station senses the carrier to confirm the medium is idle before sending a frame; if a collision is detected—indicated by signal distortion—the transmission is aborted immediately, and a 32-bit jam signal is sent to ensure all stations recognize the event. To minimize repeated collisions, stations implement a truncated binary exponential backoff algorithm, selecting a random delay from 0 to slot times (where is the collision count, up to 10) before retrying, with the slot time defined as 512 bit times for classic Ethernet. This mechanism supports efficient shared-medium operation but is constrained by network diameter, as signals must propagate across the maximum segment length (typically 2500 meters at 10 Mbps) within the frame transmission time. To guarantee collision detection, frames must meet a minimum size of 64 bytes (excluding preamble and start frame delimiter), achieved by padding shorter payloads; this ensures the frame duration exceeds the round-trip propagation delay plus jam signal time. Additionally, a minimum interframe gap of 96 bit times—9.6 μs at 10 Mbps—separates transmissions, providing receivers time to synchronize and process incoming frames.[41][42][28] Ethernet uses 48-bit MAC addresses to uniquely identify network interfaces, structured as six octets in canonical format, with the first three octets forming the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI) assigned by the IEEE Registration Authority to vendors for global uniqueness. The least significant bit of the first octet distinguishes unicast addresses (0, for individual stations) from multicast addresses (1, for group delivery to multiple recipients), while the all-ones address (FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF) serves as the broadcast address to reach all stations in the local network. These addresses enable direct frame routing within broadcast domains, with OUIs ensuring no overlap in vendor-assigned portions.[43][44] Full-duplex operation, standardized in IEEE 802.3x (1997), extends the MAC for point-to-point links using separate transmit and receive paths, eliminating CSMA/CD since collisions cannot occur. This mode doubles effective throughput by allowing simultaneous bidirectional communication and introduces a MAC Control sublayer for optional flow control via pause frames—special MAC frames with opcode 0x0001 and destination 01-80-C2-00-00-01—that instruct the receiver to suspend transmission for a specified quanta (up to 65,535 slot times), preventing buffer overflow in congested switches. Pause frames can be extended or zeroed to resume flow, negotiated via autonegotiation on twisted-pair media.[45] A key evolution in the MAC layer is support for virtual local area networks (VLANs) through IEEE 802.1Q tagging, which inserts a 4-byte tag (Tag Protocol Identifier 0x8100 plus 12-bit VLAN ID) immediately after the source MAC address in the frame header. This enables bridges and switches to segregate traffic into logical networks at the MAC level, preserving address space efficiency while allowing multiple VLANs over a single physical link, without altering core framing or access mechanisms.[46]Ethernet Topologies and Components

Shared Medium and Collision Domains

Early Ethernet networks employed a bus topology, where all devices shared a single communication medium, typically a thick coaxial cable known as 10BASE5 or "Thicknet." This physical bus formed a logical multi-access segment, allowing multiple stations to connect via vampire taps—specialized connectors that pierced the cable's insulation to attach transceivers without disrupting the signal. The IEEE 802.3 standard specified a maximum segment length of 500 meters for 10BASE5, ensuring signal integrity across the shared medium while supporting up to 100 stations per segment.[47][6] In this shared medium environment, all transmissions occurred in a single collision domain per segment, where simultaneous attempts to send data by multiple stations could result in packet overlaps and interference. To manage access, Ethernet utilized Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Detection (CSMA/CD), a protocol where stations listen to the medium before transmitting (carrier sense), allow multiple stations to attempt access (multiple access), and detect collisions during transmission by monitoring for signal distortions. Upon detecting a collision, the transmitting station aborts the frame, sends a jam signal to alert others, and schedules a retransmission using an exponential backoff algorithm that doubles the wait time after each successive collision for that frame, up to a maximum of 16 attempts. This mechanism ensured fair access but introduced delays under contention.[48][47] The half-duplex nature of shared medium Ethernet meant bandwidth was contention-based and divided among all stations, leading to inefficiencies as network load increased. Under light load, efficiency approached 95% for large packets exceeding 4000 bits, but at high utilization with smaller slot-sized packets (around 512 bits), throughput dropped to approximately 37% due to frequent collisions and retransmissions. Hubs, functioning as multiport repeaters, extended collision domains by regenerating signals across multiple segments while maintaining a single shared domain, though this amplified contention in larger networks.[48] By the 1990s, the scalability limitations of shared medium Ethernet—such as bandwidth bottlenecks and collision overhead—led to its decline, as switched architectures enabled dedicated full-duplex links per station, eliminating collision domains and improving performance.[2][6]Repeaters, Hubs, Bridges, and Switches

Repeaters are physical layer (Layer 1) devices in the OSI model that regenerate and amplify Ethernet signals to extend the physical reach of a network beyond the limitations of a single segment.[49] They operate transparently by receiving a signal on one port, cleaning it of noise, and retransmitting it to all other ports without interpreting the data content.[49] In early 10 Mbps Ethernet networks defined by IEEE 802.3, repeaters were constrained by the 5-4-3 rule, which allowed a maximum of five segments connected by up to four repeaters, with only three segments populated by end stations, to maintain signal integrity and limit round-trip delay.[50] Hubs function as multiport repeaters, enabling the connection of multiple devices to form a single shared Ethernet segment at the physical layer.[51] By broadcasting incoming signals from any port to all other ports, hubs create a unified collision domain where all connected devices compete for medium access using CSMA/CD, potentially leading to reduced performance under heavy load.[52] Hubs are classified as unmanaged, which are simple plug-and-play devices offering no configuration or monitoring capabilities, or managed, which provide basic SNMP-based oversight for diagnostics like port statistics and error rates, though managed hubs are less common today due to the prevalence of switches.[53] Bridges operate at the data link layer (Layer 2) to connect multiple Ethernet segments, filtering traffic based on MAC addresses to reduce unnecessary broadcasts and improve efficiency.[54] They employ a learning mechanism to build a dynamic table of MAC addresses and their associated ports, forwarding frames only to the relevant segment while discarding those destined for local traffic.[54] To prevent loops in redundant topologies, bridges use the Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) specified in IEEE 802.1D, which elects a root bridge and blocks redundant paths to form a loop-free tree structure.[55] Switches represent an evolution of bridges, typically featuring multiple high-speed ports that enable dedicated, full-duplex communication between connected devices, eliminating collisions within each port pair.[56] By creating microsegments—individual collision domains per port—switches support higher throughput and scalability compared to shared-medium hubs.[52] Modern switches incorporate VLAN support via IEEE 802.1Q tagging, allowing logical segmentation of broadcast domains across physical ports for enhanced security and traffic management. The development of application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC)-based switches in the late 1990s enabled Gigabit speeds, with further advancements in the mid-2000s supporting higher speeds like 10 Gb/s and beyond, by providing dedicated hardware for fast packet forwarding and buffering, reducing latency and supporting dense port configurations.[57] More recently, integration with Software-Defined Networking (SDN) has introduced programmable control planes, allowing centralized management of switch behaviors through open standards like OpenFlow, which decouples forwarding from routing decisions for greater flexibility in enterprise and data center environments.[58]Frame Format and Protocols

Ethernet Frame Structure

The Ethernet frame, as specified in IEEE 802.3, encapsulates data for transmission across local area networks, ensuring synchronization, addressing, protocol identification, and error detection.[59] The standard frame format includes a preamble for clock synchronization, address fields for endpoint identification, a protocol indicator, variable-length data, and a checksum for integrity verification.[60] This structure supports reliable delivery in both half-duplex and full-duplex modes, with a minimum frame size of 64 bytes and a maximum of 1518 bytes excluding the preamble and inter-frame gap.[59] The frame begins with a 7-byte preamble consisting of the repeating pattern 10101010 (in binary), which allows the receiver to synchronize its clock with the sender's timing.[60] This is immediately followed by a 1-byte Start Frame Delimiter (SFD) of 10101011, signaling the end of synchronization and the start of the actual frame data.[60] Together, these 8 bytes prepare the physical layer for processing the subsequent fields.[59] Following synchronization, the 6-byte destination MAC address specifies the intended recipient, which can be a unicast, multicast, or broadcast address.[60] The subsequent 6-byte source MAC address identifies the transmitting device.[60] These 48-bit addresses, managed by the IEEE, enable direct communication within the local network segment. The 2-byte EtherType/Length field serves a dual purpose: if its value is 1500 (0x05DC) or less, it indicates the length of the payload in bytes; if greater, it denotes the EtherType, identifying the higher-layer protocol encapsulated in the payload.[60] For example, the EtherType value 0x0800 signifies IPv4.[61] EtherType assignments are maintained by the IEEE Registration Authority to prevent conflicts. The payload field carries the upper-layer protocol data, ranging from 46 to 1500 bytes.[60] To enforce the minimum frame size and ensure proper collision detection in shared media, any payload shorter than 46 bytes is padded with zeros until it reaches this length.[60] The total frame length, from destination address to end of payload, must thus be at least 64 bytes including the 4-byte FCS.[59] The frame terminates with a 4-byte Frame Check Sequence (FCS), a 32-bit cyclic redundancy check (CRC-32) computed over the destination address, source address, EtherType/Length, and payload fields.[60] The CRC uses the generator polynomial: This polynomial, defined in IEEE 802.3, detects burst errors up to 32 bits and most multi-bit errors, with the receiver recomputing and comparing the CRC to verify integrity.[62][59] For virtual LAN (VLAN) segmentation, IEEE 802.1Q modifies the frame by inserting a 4-byte tag between the source MAC address and EtherType/Length field, increasing the maximum frame size to 1522 bytes.[46] The tag comprises a 2-byte Tag Protocol Identifier (TPID) fixed at 0x8100 to denote an 802.1Q frame, and a 2-byte Tag Control Information (TCI) field that includes a 3-bit priority code, a 1-bit Canonical Format Indicator, and a 12-bit VLAN Identifier (VID) for network partitioning.[63] Jumbo frames extend the standard payload limit beyond 1500 bytes, often to 9000 bytes or more, to reduce header overhead and improve throughput in high-speed, low-latency environments like data centers.[64] While not part of the core IEEE 802.3 specification, this extension is widely supported in modern Ethernet implementations for efficiency gains.[59]| Field | Size (bytes) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Preamble | 7 | Clock synchronization |

| SFD | 1 | Frame start delimiter |

| Destination MAC | 6 | Recipient address |

| Source MAC | 6 | Sender address |

| EtherType/Length | 2 | Protocol type or payload length |

| Payload (padded) | 46–1500 | Data (with padding if needed) |

| FCS | 4 | Error detection (CRC-32) |

| Total (standard) | 64–1518 | Excluding preamble/SFD |

Autonegotiation and Speed Negotiation

Autonegotiation is a protocol defined in the IEEE 802.3 standard that enables Ethernet devices connected via twisted-pair cabling to automatically select the highest common transmission parameters, such as speed, duplex mode, and flow control capabilities, prior to establishing a link. This process occurs at the physical layer and ensures interoperability between devices with varying capabilities, reducing manual configuration errors and optimizing link performance. Originally introduced as an optional feature for Fast Ethernet, autonegotiation has become mandatory for many subsequent twisted-pair physical layer specifications to support plug-and-play connectivity.[65] For 10 Mbps and 100 Mbps Ethernet over twisted pair, autonegotiation is specified in Clause 28 of IEEE 802.3, utilizing Fast Link Pulses (FLPs) to exchange capabilities between link partners. FLPs are bursts of clock pulses modulated with data, compatible with the 10BASE-T normal link pulses, allowing devices to advertise supported modes like 10BASE-T half-duplex, 10BASE-T full-duplex, 100BASE-TX half-duplex, or 100BASE-TX full-duplex.[65] The protocol includes parallel detection, which enables negotiation with legacy devices that do not support autonegotiation by monitoring the incoming signal for characteristics of specific speeds and duplex modes. Upon successful exchange, the devices configure the link at the highest mutually supported speed and preferred duplex mode; if negotiation fails, the link may default to a lower-speed half-duplex operation to maintain basic connectivity.[65] Gigabit Ethernet extends autonegotiation through Clause 40, which builds on Clause 28 by incorporating a page exchange mechanism to handle additional parameters required for 1000BASE-T operation. In this process, base pages are first exchanged to advertise core capabilities, such as speed and duplex, while next pages provide further details like support for pause frames used in flow control.[66] For 1000BASE-T, autonegotiation is mandatory and also determines master-slave timing to prevent echo on the bidirectional twisted-pair medium, ensuring stable signal transmission. The protocol supports fallback to 100 Mbps or 10 Mbps if Gigabit modes cannot be agreed upon, prioritizing link establishment over maximum speed. At higher speeds of 10 Gbps and beyond, particularly for backplane and copper applications, autonegotiation evolves into link training protocols, as defined in amendments like IEEE 802.3ap for backplane Ethernet. Clause 72 of 802.3ap specifies a startup procedure using training frames to adapt transmitter equalization and receiver settings, compensating for signal distortions in high-speed serial links over backplanes.[67] This training phase includes coefficient exchange to optimize the channel, followed by error correction validation before entering data mode; failure to converge may result in link failure or reversion to a lower-rate mode if supported.[68] Energy Efficient Ethernet (EEE), introduced in IEEE 802.3az, integrates with autonegotiation to enable power-saving modes during periods of low link utilization. During negotiation, devices can advertise EEE support via dedicated bits in the base or next pages, allowing the link to transition to a low-power idle (LPI) state where the physical layer signaling is quiesced, reducing power consumption by up to 50% on copper interfaces without interrupting the logical link.[69] EEE is applicable to speeds from 100 Mbps to 10 Gbps and requires mutual agreement to avoid compatibility issues, with failure modes including fallback to non-EEE operation if one partner does not support it.[70] The overall autonegotiation process relies on a structured exchange of information: devices transmit FLP bursts or equivalent signaling containing link code words that encode capabilities, with arbitration resolving any conflicts in favor of the highest performance mode. Base pages handle primary parameters like speed and duplex, while next pages extend negotiation for optional features such as flow control via IEEE 802.3x pause or priority-based flow control.[66] Common failure modes include mismatched capabilities leading to half-duplex fallback, signal integrity issues causing repeated negotiation attempts, or timeouts resulting in no link; in such cases, manual intervention or device reconfiguration may be required to resolve the impasse.[65]Variants and Applications

Speed Variants and Media Types

Ethernet has evolved through a series of speed variants defined by the IEEE 802.3 standards, each paired with specific physical media types to support increasing data rates while maintaining compatibility with existing infrastructure.[28] These variants range from the original 10 Mbps implementations using coaxial and twisted-pair cabling to modern terabit-per-second capabilities over fiber optics, driven by demands for higher bandwidth in enterprise, data center, and high-performance computing environments.[71] The foundational 10 Mbps Ethernet, standardized in IEEE 802.3, included 10BASE-T, which operates over unshielded twisted-pair (UTP) cabling such as Category 3 (Cat3), supporting distances up to 100 meters with Manchester encoding for reliable transmission. Complementary fiber-based options like 10BASE-F variants, including 10BASE-FL for up to 2 km over multimode fiber, enabled longer reaches in early local area networks. Fast Ethernet at 100 Mbps, defined in IEEE 802.3u, introduced 100BASE-TX, utilizing two pairs of Category 5 (Cat5) UTP copper cabling for up to 100 meters with 4B/5B encoding and MLT-3 signaling to achieve full-duplex operation.[72] For extended distances, 100BASE-FX employs multimode fiber with ST or SC connectors, supporting up to 2 km at 850 nm wavelength, making it suitable for backbone connections.[73] Gigabit Ethernet, per IEEE 802.3ab and 802.3z, brought 1000BASE-T to four pairs of Cat5e UTP copper, enabling 1 Gbps over 100 meters through PAM-5 encoding and echo cancellation techniques. Fiber variants include 1000BASE-SX for short-range multimode fiber (up to 550 m at 850 nm) and 1000BASE-LX for single-mode or multimode fiber (up to 10 km at 1310 nm), using LC connectors for versatility in mixed environments. Higher speeds beyond 1 Gbps shifted emphasis toward data centers. The 10 Gbps standard IEEE 802.3an specifies 10GBASE-T over augmented Category 6 (Cat6a) UTP or shielded twisted-pair cabling, supporting 100 meters with DSQ128 encoding to mitigate crosstalk. For 40 Gbps and 100 Gbps under IEEE 802.3ba, 40GBASE-SR4 and 100GBASE-SR4 use parallel multimode fiber (MMF) with MPO connectors, transmitting over four lanes at 850 nm for distances up to 100 m (OM3) or 150 m (OM4). Similarly, 400 Gbps in IEEE 802.3bs includes 400GBASE-DR4, which leverages four parallel lanes of single-mode fiber (SMF) at 1310 nm with MPO-12 connectors, achieving up to 500 m using PAM4 modulation. As of 2025, 800 Gbps Ethernet, defined in IEEE 802.3df-2024, employs PAM4 signaling over SMF for variants like 800GBASE-DR8, supporting eight parallel lanes at 1310 nm for up to 500 m, to meet hyperscale data center needs.[74][71] The roadmap for 1.6 Tbps Ethernet, under IEEE P802.3dj (ongoing as of 2025), targets short-reach applications in AI clusters using 200 Gbps PAM4 per lane over copper or fiber backplanes, with initial deployments anticipated by 2027 to handle massive parallel processing workloads.[75][76]| Speed | Key Standard | Primary Media Type | Max Distance | Example Encoding/Modulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|