Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Multicast

View on Wikipedia

| Routing schemes |

|---|

| Unicast |

| Broadcast |

| Multicast |

| Anycast |

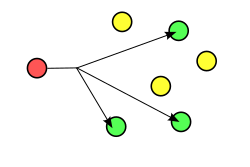

In computer networking, multicast is a type of group communication where data transmission is addressed to a group of destination computers simultaneously.[1] Multicast can be one-to-many or many-to-many distribution.[2][3] Multicast differs from physical layer point-to-multipoint communication.

Group communication may either be application layer multicast[1] or network-assisted multicast, where the latter makes it possible for the source to efficiently send to the group in a single transmission. Copies are automatically created in other network elements, such as routers, switches and cellular network base stations, but only to network segments that currently contain members of the group. Network assisted multicast may be implemented at the data link layer using one-to-many addressing and switching such as Ethernet multicast addressing, Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM), point-to-multipoint virtual circuits (P2MP)[4] or InfiniBand multicast. Network-assisted multicast may also be implemented at the Internet layer using IP multicast. In IP multicast the implementation of the multicast concept occurs at the IP routing level, where routers create optimal distribution paths for datagrams sent to a multicast destination address.

Multicast is often employed in Internet Protocol (IP) applications of streaming media, such as IPTV and multipoint videoconferencing.

Ethernet

[edit]Ethernet frames with a value of 1 in the least-significant bit of the first octet of the destination address are treated as multicast frames and are flooded to all points on the network. This mechanism constitutes multicast at the data link layer. This mechanism is used by IP multicast to achieve one-to-many transmission for IP on Ethernet networks. Modern Ethernet controllers filter received packets to reduce CPU load, by looking up the hash of a multicast destination address in a table, initialized by software, which controls whether a multicast packet is dropped or fully received.

Ethernet multicast is available on all Ethernet networks. Multicasts span the broadcast domain of the network. Multiple Registration Protocol can be used to control Ethernet multicast delivery.

IP

[edit]

IP multicast is a technique for one-to-many communication over an IP network. The destination nodes send Internet Group Management Protocol membership report and leave group messages, for example in the case of IPTV when the user changes from one TV channel to another. IP multicast scales to a larger receiver population by not requiring prior knowledge of who or how many receivers there are. Multicast uses network infrastructure efficiently by requiring the source to send a packet only once, even if it needs to be delivered to a large number of receivers. The nodes in the network take care of replicating the packet to reach multiple receivers only when necessary.

The most common transport layer protocol to use multicast addressing is User Datagram Protocol (UDP). By its nature, UDP is not reliable—messages may be lost or delivered out of order. By adding loss detection and retransmission mechanisms, reliable multicast has been implemented on top of UDP or IP by various middleware products, e.g. those that implement the Real-Time Publish-Subscribe (RTPS) Protocol of the Object Management Group (OMG) Data Distribution Service (DDS) standard, as well as by special transport protocols such as Pragmatic General Multicast (PGM).

IP multicast is always available within the local subnet. Achieving IP multicast service over a wider area requires multicast routing. Many networks, including the Internet, do not support multicast routing. Multicast routing functionality is available in enterprise-grade network equipment but typically needs to be configured by a network administrator. The Internet Group Management Protocol is used to control IP multicast delivery.

Application layer

[edit]Application layer multicast overlay services are not based on IP multicast or data link layer multicast. Instead, they use multiple unicast transmissions to simulate a multicast. These services are designed for application-level group communication. Internet Relay Chat (IRC) implements a single spanning tree across its overlay network for all conference groups.[5] The lesser-known PSYC technology uses custom multicast strategies per conference.[6] Some peer-to-peer technologies employ the multicast concept known as peercasting when distributing content to multiple recipients.

Explicit multi-unicast (Xcast) is another multicast strategy that includes addresses of all intended destinations within each packet. As such, given maximum transmission unit limitations, Xcast cannot be used for multicast groups with many destinations. The Xcast model generally assumes that stations participating in the communication are known ahead of time so that distribution trees can be generated and resources allocated by network elements in advance of actual data traffic.[7]

Wireless networks

[edit]Wireless communications (with the exception of point-to-point radio links using directional antennas) are inherently broadcasting media. However, the communication service provided may be unicast, multicast, or broadcast, depending on if the data is addressed to an individual node, a specific group of nodes, or all nodes in the covered network, respectively.

Wireless networks use electromagnetic waves to transmit data through the air, enabling devices to connect and communicate without physical cables. These networks come in various types, including Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, cellular, and satellite networks, each serving different purposes.

Types of Wireless Communication

[edit]Unicast: In a unicast wireless communication, data is transmitted from a single source to a single, specific receiver. This is typical in point-to-point communication, where a device sends data directly to another device. Examples include internet browsing or file downloads.

Multicast: In multicast communication, data is sent from one source to multiple specific receivers, often to a defined group within a network. This is efficient in scenarios like live streaming, where the data is only sent once but received by multiple devices interested in the same content.

Broadcast: Broadcast communication involves sending data from one source to all devices within the network's range. In this case, every device receives the same data, regardless of whether it is requested. Examples of broadcast communication include certain emergency alerts and some radio communications.

Security Considerations: Wireless networks are more vulnerable to security threats compared to wired networks, primarily because their signals can be intercepted more easily. Common security measures include encryption protocols such as WPA3 for Wi-Fi networks, firewalls, and the use of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) to safeguard communication.

Advantages and Challenges: Wireless networks offer flexibility and mobility, allowing users to connect devices without being tethered to a physical connection. However, they can be affected by interference from physical obstacles, environmental factors, or even other wireless devices, leading to slower speeds or connection issues.[8]

Television

[edit]In digital television, the concept of multicast service sometimes is used to refer to content protection by broadcast encryption, i.e. encrypted pay television content over a simplex broadcast channel only addressed to paying viewers. In this case, data is broadcast to all receivers but only addressed to a specific group.

The concept of interactive multicast, for example using IP multicast, may be used over TV broadcast networks to improve efficiency, offer more TV programs, or reduce the required spectrum. Interactive multicast implies that TV programs are sent only over transmitters where there are viewers and that only the most popular programs are transmitted. It relies on an additional interaction channel (a back-channel or return channel), where user equipment may send join and leave messages when the user changes TV channel. Interactive multicast has been suggested as an efficient transmission scheme in DVB-H and DVB-T2 terrestrial digital television systems,[9] A similar concept is switched broadcast over cable TV networks, where only the currently most popular content is delivered in the cable-TV network.[10] Scalable video multicast in an application of interactive multicast, where a subset of the viewers receive additional data for high-resolution video.

TV gateways converts satellite (DVB-S, DVB-S2), cable (DVB-C, DVB-C2) and terrestrial television (DVB-T, DVB-T2) to IP for distribution using unicast and multicast in home, hospitality and enterprise applications

Another similar concept is Cell-TV, and implies TV distribution over 3G cellular networks using the network-assisted multicasting offered by the Multimedia Broadcast Multicast Service (MBMS) service, or over 4G/LTE cellular networks with the eMBMS (enhanced MBMS) service.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Media-communication based on Application-Layer Multicast

- ^ Lawrence Harte, Introduction to Data Multicasting, Althos Publishing 2008.

- ^ Li, Bing; Atwood, J. William (2016-06-19). "Secure receiver access control for IP multicast at the network level: Design and validation". Computer Networks. 102: 109–128. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2016.03.010. ISSN 1389-1286.

- ^ M. Noormohammadpour; et al. (July 10, 2017). "DCCast: Efficient Point to Multipoint Transfers Across Datacenters". USENIX. Retrieved July 26, 2017 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Reed, D. (May 1992). "A Discussion on Computer Network Conferencing". IETF Datatracker. sec. 2.5.1. RFC 1324.

- ^ v. Loesch, Carlo (2007), Whitepaper on PSYC, EU: PSYC.

- ^ Rick Boivie; Nancy Feldman; Yuji Imai; Wim Livens & Dirk Ooms (November 2007). "Explicit Multicast (Xcast) Concepts and Options". Internet Engineering Task Force Datatracker. doi:10.17487/RFC5058. RFC 5058. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^ Stallings, William (2009). Wireless Communications & Networks (2nd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 9788131720936.[page needed]

- ^ M. Eriksson, S.M. Hasibur Rahman, F. Fraille, M. Sjöström, ”Efficient Interactive Multicast over DVB-T2 - Utilizing Dynamic SFNs and PARPS”, 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (BMSB’13), London, UK, June 2013.

- ^ N. Sinha, R. Oz and S. V. Vasudevan, “The statistics of switched broadcast”, Proceedings of the SCTE 2005 Conference on Emerging Technologies, Tampa, FL, USA, January 2005