Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Malta Police Force

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2019) |

| Malta Police Il-Korp tal-Pulizija ta’ Malta | |

|---|---|

Malta Police Force Logo | |

Official Insignia | |

Flag of the Malta Police Force | |

| Common name | Il-Pulizija |

| Motto | Domine Dirige Nos Lord Guide Us |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 12 July 1814 |

| Annual budget | €76,480,000 (2020)[1] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| National agency (Operations jurisdiction) | Malta |

| Operations jurisdiction | Malta |

| |

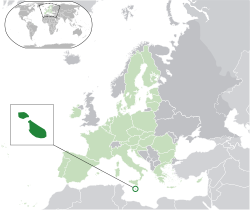

| Map of Malta Police's jurisdiction | |

| Size | 316 km² |

| Population | 475,700[2] |

| Legal jurisdiction | As per operations jurisdiction |

| Constituting instrument |

|

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Police General Headquarters, Pjazza San Kalcidonju, Floriana FRN 1530, Malta |

| Police Officers | 2.400 (2020) |

| Civilians | 102 (2018) |

| Minister responsible |

|

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | Ministry for Home Affairs, Security, Reforms & Equality |

| Notables | |

| Anniversary |

|

| Website | |

| pulizija | |

| Emergency Telephone Number 112 Crime Stop Line 119 | |

The Malta Police Force (Maltese: Il-Korp tal-Pulizija ta’ Malta) is the national police force of the Republic of Malta. It falls under the responsibility of the Ministry for Home Affairs, Security, Reforms & Equality and its objectives are set out in The Police Act, Chapter 164[3] of the Laws of Malta.

As of 2020, the force is made up of around 2,400 members.

Organisation

[edit]The duty of the executive police is to preserve public order and peace, to prevent and to detect and investigate offences, to collect evidence and to bring the offenders, whether principals or accomplices, before the judicial authorities.

Specialised Branches:[4]

- Anti-Money Laundering

- Community Policing

- Counter Terrorism Unit (CTU)

- Criminal Intelligence & Analysis Unit (CIAU)

- Cyber Crime Unit (CCU)

- Domestic Violence Unit (DSQ)

- Drugs Squad (DSQ)

- Economic Crimes

- Environment Protection Unit (EPU)

- Gender-Based & Domestic Violence (GBDV)

- Homicide

- Immigration

- International Relations Unit (IRU)

- K9 Section

- Major Crimes (CID)

- Mounted Section

- Rapid Intervention Unit (RIU)

- Special Intervention Unit (SIU)

- Stolen Vehicle Squad (SVS)

- Traffic

- Vice Squad (VSQ)

- Victim Support Unit (VSU)

Ranks

[edit]| Insignia[5][6] | Name | English |

|---|---|---|

|

Kummisarju | Commissioner of police |

| Deputat Kummisarju | Deputy commissioner | |

|

Assistent Kummisarju | Assistant commissioner |

|

Supretendent | Superintendent |

| Spettur | Inspector | |

|

Surġent Maġġur I | Sergeant major I |

|

Surġent Maġġur II | Sergeant major II |

|

Surġent | Police sergeant |

|

Kuntisstabli | Police constable |

History

[edit]The Malta Police Force is one of the oldest police forces in Europe. In its present form, it dates from a proclamation during the governorship of Sir Thomas Maitland (1813–1814). When Malta became a crown colony of the United Kingdom by the Treaty of Paris, Maitland was appointed Governor and commander-in-chief of Malta and its dependencies by the Prince Regent's Commission of 23 July 1813. On his appointment Maitland, embarked on many far reaching reforms, including the maintenance of law and order.[7]

By Proclamation XXII of 1 July 1814, Maitland ordered and directed that all powers up to then exercised with respect to the administration of the police of the island of Malta and its dependencies were to be administered by the authorities under established procedures, after 12 July 1814.[7]

The police was to be divided into two distinct departments – the executive police and the judicial. The inspector general of police (nowadays the commissioner of police) was to be the head of the executive police, and received orders from the governor. The magistrates of police for Malta and for Gozo were to be the heads of the judicial police.[7]

After the grant of self-government in 1921, the police department became the responsibility of the Maltese government. The first minister appointed, who was responsible for justice and the police, was Dr Alfredo Caruana Gatto.[7]

General headquarters

[edit]The Police Depot, as it is known today, was built by the Portuguese Grand Master Manoel De Vilhena in 1734 and at first it served as an institute called Casa D'Industria, a home for homeless women. They were taught basic skills and education such as reading, writing and some trades like weaving, carding and processing cotton.

In 1850, during the British occupation period, this building was used as the General Hospital. Beneath this building, a shelter was dug at the beginning of the Second World War in order to tend to wounded patients who could not be easily moved from one place to another. This space therefore provided a safer environment for patients during air bombardments. This is not only the only shelter in the Maltese Islands used for this function. There is no known underground hospital on the continent that was built or dug out to operate in this way.

It was in 1954 that the Police Force moved into this building and turned it into its General Headquarters, from where it still operates today.[8]

Police museum

[edit]The museum is divided into two sections: each section is housed in a separate hall. The first section deals with the administrative history of the force and the second part is about some of the criminal cases.

In the first hall, one will see various objects and belongings, for example uniforms, badges, medals, decorations, weapons and many other interesting things including tools and vehicles which were all required and used in different periods which helped the Police Force to carry out its duty to the best of its ability.

In the second hall one can see made-up scenes of crime that happened in Malta.[8]

Police commissioners

[edit]- Col Francesco Rivarola (1814–1822)

- Lt Col Henry Balneavis (1822–1832)

- Charles Godfrey (1832–1844)

- Frederick Sedley (1845–1858)

- Hector Zimelli (1858–1869)

- Raffaele Bonello (1869–1880)

- Col Attillo Sceberras (1880–1884)

- Capt. Richard Casolani, RMFA (1884–1888)

- Melitone Caruana (1888–1890)

- Comm. Hon. Clement La Primaudaye, MVO., RN (1890–1903)

- Tancred Curmi (1903–1915)

- Claude W. Duncan (1916–1919)

- Col Henry W. Bamford, OBE (1919–1922)

- Antonio Busuttil (1922–1923)

- Mjr Frank Stivala (1923–1928)

- Captain Salvatore Galea (1928–1939)

- Lt Col Gustavus S. Brander, OBE (1930–1932)

- Joseph Axisa (1939–1947)

- Joseph Ullo (1947–1951)

- Herbert Grech, CVO (1951–1954)[9]

- George Cachia, L.P. (1954–1956)

- Vivian Byres de Gray, MVO., MBE., BEM (1956–1971)

- Comm. Alfred J. Bencini (1971–1973)

- Edward Bencini (1973–1974)

- Enoch Tonna (1974–1977)

- John N. Cachia (1977–1980)

- Dr Lawrence Pullicino, LL.D. (1980–1987)

- Bgdr. John Spiteri, AFM (1987–1988)

- Alfred A. Calleja (1988-1992)

- George Grech (1992–2001)

- John Rizzo (2001–2013)

- Peter Paul Zammit, L.P. (2013–2014)

- Michael Cassar (2014–2016)

- Lawrence Cutajar (2016–2020)

- Angelo Gafa (2020–)

References

[edit]- ^ "The Budget Speech 2020" (PDF). mfin.gov.mt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Eurostat: Population on 1 January" (PDF). Eurostat. 14 June 2018.

- ^ Police Act, 2017 (Act No. XVIII of 2017) (Act XVIII). 2017.

- ^ "Organisational Chart". pulizija.gov.mt. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Police Force Ranks". pulizija.gov.mt. The Malta Police Force. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "Police Force Ranks". homeaffairs.gov.mt. Post of First Class Sergeant - Major in the Malta Police Force. 10 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d "History of the Malta Police". pulizija.gov.mt. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Police Museum". pulizija.gov.mt. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ London Gazette, May 1954

External links

[edit]Malta Police Force

View on GrokipediaRole and Mandate

Legal Foundation and Core Duties

The Malta Police Force derives its legal foundation from the Police Act (Chapter 164) of the Laws of Malta, which establishes the statutory framework for its organization, discipline, and operational mandate. Enacted as Act No. XVIII of 2017 on April 28, 2017, this legislation repealed earlier ordinances, including the 1961 version, and consolidates provisions governing the Force's structure and authority as the primary civilian law enforcement agency of the Republic.[8][9] The Act vests the Force with executive powers to uphold the rule of law, subject to oversight by the Ministry for Home Affairs and National Security, ensuring alignment with Malta's constitutional obligations for public safety.[8] Core duties encompass preserving public order and peace, preventing offences, and enforcing legal observance as a foundational safeguard for citizens' rights. These include proactive measures to combat crime, maintain national security, and investigate violations across Malta, Gozo, and Comino, with the Force serving as the lead entity for both preventive policing and criminal inquiries.[2][10] In practice, officers exercise powers of arrest, search, and detention under the Act to address immediate threats to safety, while collaborating with communities to enhance overall security without delegating core enforcement roles to auxiliary civilian staff.[8][11]Jurisdiction and Powers

The Malta Police Force exercises exclusive jurisdiction for internal law enforcement across the entire territory of the Republic of Malta, including the main islands of Malta, Gozo, and Comino, as well as territorial waters extending up to 12 nautical miles offshore where police powers apply in coordination with maritime authorities.[12][13] This national scope ensures centralized control without devolved regional policing, enabling rapid response to crimes and public order threats throughout the 316 square kilometers of land area.[11] Under the Police Act (Chapter 164 of the Laws of Malta), the Force's core duties encompass preserving public order and peace, preventing offences, promoting enforcement of all laws as a safeguard for individual rights and liberties, detecting crimes, collecting evidence, apprehending fugitives, and prosecuting offenders through judicial processes.[8][14] These objectives position the police as the primary executive authority for maintaining internal security, distinct from the Armed Forces of Malta's role in external defense and limited domestic support.[15] Police powers include the authority to arrest individuals without a warrant upon reasonable suspicion of an offence, conduct warrantless stops and searches of persons or vehicles if there are grounds to believe evidence of a crime will be found, and use proportional force—including firearms in cases of imminent threat to life or widespread violence—to neutralize dangers.[16][17] Such powers are exercised under strict legal constraints to prevent abuse, with accountability mechanisms including internal inquiries by the Commissioner and judicial oversight, reflecting the Act's emphasis on balancing enforcement efficacy with civil liberties.[8] International cooperation extends jurisdiction indirectly through joint operations and extradition under Article 92, allowing liaison with foreign forces for cross-border crimes affecting Malta.[18]History

Establishment and British Colonial Period (1814–1964)

The Malta Police Force was established on 12 July 1814 through Proclamation XXII issued by British Governor Sir Thomas Maitland on 1 July 1814, centralizing fragmented policing authorities previously held by figures such as the Castellan, Captain of the Rod, criminal judges, magistrates, the Advocate Fiscal, and the Governor of Gozo.[19][20] This reform addressed inefficiencies in pre-British systems under the Knights of St. John and French occupation, modeling the new force on the English system with a separation of executive and judicial functions to enhance law and order during Malta's transition to a British Crown Colony, confirmed by the Treaty of Paris.[3][19] The force was structured into an executive branch led by an Inspector General—initially Francesco Rivarola, a Corsican serving in the British Army—and a judicial branch overseen by magistrates, dividing Malta into districts for enforcement.[20][19] Key reforms prohibited torture, limited detentions to 48 hours without charges (with scrutiny within 10 days), mandated open court trials, and required itemized records of seizures with witnesses, establishing a civil rather than military policing model where officers carried swords, pistols, and batons but lacked initial uniforms.[19] By 1842, the force comprised 1 inspector, 49 officers, and 159 constables operating from 45 stations across two main districts (Valletta and Mdina areas), though sanctuary rights in churches initially hindered arrests until their abolition in 1828.[20] In 1850, under Governor Sir Richard More O’Ferrall, further reorganization reduced commissioned officers to 30 while introducing 27 first-class constables, refining the hierarchy that evolved to include formalized ranks and uniforms by 1870.[20] Throughout the British colonial era, the police maintained order amid growing administrative demands, adapting to challenges like plague prevention in 1814 and post-World War II smuggling enforcement at ports.[21] In 1921, with Malta's partial self-governance, control shifted to local authorities, emphasizing community policing while retaining British-influenced structures until independence in 1964.[3] The force's civil focus and procedural safeguards from Maitland's proclamation endured, influencing Malta's criminal law framework.[19]Post-Independence Era (1964–2004)

Upon Malta's attainment of independence on September 21, 1964, the Malta Police Force transitioned fully to local control under the Maltese government, ending residual British oversight as stipulated by the Malta Independence Act.[22] This shift aligned the force with national sovereignty, with the Police Act (Chapter 164 of the Laws of Malta) continuing to define its mandate for law enforcement, public order maintenance, and crime prevention across the islands.[3] The 1970s and early 1980s were marked by frequent leadership instability amid political turbulence under Prime Minister Dom Mintoff's Labour administrations (1971–1984). Commissioners such as Alfred Bencini (1972–1973) resigned following clashes with Mintoff over personnel transfers, while Enoch Tonna (1974–1977) was asked to resign and Lawrence Pullicino (1980–1987) was compulsorily retired on public interest grounds.[23] The force faced accusations of politicization, including alleged bias in handling opposition Nationalist Party gatherings, as seen during the 1979 Black Monday violence when Labour supporters attacked the Progress Press offices and Eddie Fenech Adami's residence, with police reportedly failing to intervene effectively or even blocking access for opposition events.[24] Similar tensions persisted into the mid-1980s, exemplified by police actions during the 1986 Tal-Barrani incident where Nationalist supporters were obstructed from attending a political meeting.[24] Following the 1987 electoral victory of the Nationalist Party, efforts intensified to depoliticize the force, including the reinstatement of officers like Alfred Calleja (commissioner 1988–1992) and expectations of a broader clean-up of entrenched influences from prior regimes.[25] George Grech served as commissioner from 1992 until his 2001 resignation amid a personal scandal, marking the end of a period of relative stability but highlighting ongoing vulnerabilities to external pressures.[23] In the 1990s, the force initiated modernization, culminating in the 1996 Change Management Programme aimed at reorienting towards community policing, improving operational efficiency, and addressing structural inefficiencies inherited from earlier decades.[26] This included efforts to enhance training, resource allocation, and public engagement, though implementation faced resistance from internal cultural norms and limited funding.[27] By 2004, these reforms laid groundwork for further adaptations, with the force maintaining a strength of approximately 1,800 personnel focused on core duties amid Malta's evolving socio-economic landscape.[21]Contemporary Developments (2004–Present)

Malta's accession to the European Union on May 1, 2004, facilitated increased international police cooperation for the Malta Police Force, including participation in EU missions and access to funding for projects enhancing operational capabilities, such as training and equipment upgrades.[28] The Force's personnel grew from approximately 1,936 officers in 2004 to 2,405 by November 2024, amid a population increase from around 400,000 to over 550,000, reflecting efforts to address rising demands from migration and urban expansion.[29] Over this period, the crime profile shifted significantly, with indoor offenses rising from 4% of total crimes in 2004 to nearly 40% by 2025, driven by socioeconomic changes and improved detection methods.[30] The assassination of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia by car bomb on October 16, 2017, exposed deficiencies in the Force's investigative processes, including delays in pursuing leads and alleged interference by then-Commissioner Lawrence Cutajar, who resigned on January 17, 2020, amid public and governmental pressure following the change in prime ministership.[31] [32] A public inquiry concluded in July 2021 that the state bore ultimate responsibility for her death due to a culture of impunity and institutional failures, including police inaction on prior threats against her, though three low-level perpetrators were convicted by 2023 with limited progress on higher-level enablers.[33] [34] [35] Angelo Gafà, appointed Commissioner on June 23, 2020, after a public selection process, implemented cosmetic changes to the Force's image but faced repeated calls for resignation over perceived continuities in investigative shortcomings and handling of corruption cases.[36] [37] In response to eroded public trust post-2017, the Force launched its Transformation Strategy 2020–2025 on September 25, 2020, targeting internal corruption, officer fitness, functional restructuring, and a shift to knowledge-based policing, with over 80% of its 49 initiatives completed by September 2025 through officer dedication and EU-aligned reforms.[38] [6] This built on EU-driven enhancements in cross-border operations and was succeeded by the Corporate Strategy 2025–2030, unveiled on September 19, 2025, under the theme "Safer Communities, Smarter Policing," emphasizing three pillars: public safety via proactive tactics, trust-building through transparency, and efficient resource use with data analytics and community engagement.[39] [6] These strategies addressed cascading effects from historical legacies, including colonial-era structures, by prioritizing Peelian principles of preventive policing and financial crime units, though challenges in enforcement amid population pressures persist.[40]Organizational Structure

Command and Administrative Hierarchy

The Malta Police Force is commanded by the Commissioner of Police, who exercises overall operational and administrative authority as the chief executive officer.[41] The position, currently held by Angelo Gafà since June 2020, is appointed by the President of Malta on the advice of the Prime Minister and reports to the Minister for Home Affairs, Security, Reforms and Equality.[42] [41] Beneath the Commissioner, the command structure includes two Deputy Commissioners responsible for key operational oversight, with Alexander Gatt appointed in March 2023 and Kenneth Haber in February 2024.[43] [44] A Director General for Strategy and Support handles consolidated administrative functions, including resource allocation and policy implementation, as part of reforms to streamline top-level management and reduce silos.[45] Administrative hierarchy is organized into specialized divisions, regional districts, and support functions to ensure efficient law enforcement across Malta's territory. As of recent restructuring, eight Assistant Commissioners oversee portfolios such as crime investigations, protective services, drugs enforcement, and economic crimes, directing superintendents in operational units.[46] Key administrative branches include the Internal Audit and Investigations Unit for maintaining professional standards; Investigations and Technical Support encompassing forensics, victim support, and crime prevention; and specialized units for organized crime, immigration, cybersecurity, and counter-terrorism.[5] Regional districts provide localized policing, while support areas cover human resources, ICT and data management, finance, projects and logistics, and strategy transformation.[5] This framework, refined through the 2020-2025 Transformation Strategy, aims to optimize span of control and accountability by defining clear remits for units and integrating functions under senior command.[45]Specialized Units and Operations

The Malta Police Force maintains specialized units to address targeted threats, including organized crime, terrorism, cyber offenses, and high-risk tactical scenarios. These units operate under divisions such as the Organised Crime Division, which tackles major financial crimes, and the Investigations & Technical Support Division, encompassing forensic science, victim support, and crime prevention efforts. Cybersecurity and counter-terrorism initiatives form core focuses, supplemented by dedicated squads for drug enforcement and gender-based violence.[5] The Special Intervention Unit (SIU), established in 2016, serves as the primary tactical response for high-risk operations, including arrests related to drug trafficking, hostage rescues, and counterterrorism warrants. It functions as a last-resort intervention in critical situations requiring specialized skills in close-quarter combat and threat neutralization.[47][48] Complementing the SIU, the Rapid Intervention Unit (RIU) provides swift tactical support in dynamic operations, such as raids on suspected drug distribution networks, where it has assisted in apprehending multiple suspects during coordinated searches.[49][50] The Counter Terrorism Unit (CTU) concentrates on mitigating terrorism risks, integrating with broader security efforts amid Malta's international relations and immigration challenges. It collaborates on assessments aligned with global standards, such as United Nations Security Council resolutions.[50][51][5] The Cybercrime Unit investigates digital offenses, offering technical expertise to general investigators on matters like data retrieval and online fraud, with reports automatically routed for specialized handling. This unit has expanded to counter emerging threats, including scams and identity theft, through dedicated sections for online fraud disruption.[18][52][53] The Drugs Squad conducts proactive enforcement against trafficking and distribution, executing raids that have yielded seizures of substances like cocaine and cannabis, alongside arrests of organized groups possessing weapons and ammunition. Recent operations, such as those in December 2024, underscore ongoing efforts yielding multiple detentions.[54][55][50] Additional units include the Vice Squad for vice-related crimes, the Gender-Based and Domestic Violence Unit (GBDVU) for violence-specific interventions, and support from the Economic Crimes Squad within financial investigations. These entities enable integrated operations, often leveraging inter-unit collaboration for complex cases involving immigration, international relations, and technical forensics.[50][5]Personnel Ranks and Training

The Malta Police Force maintains a hierarchical rank structure derived from British colonial influences, featuring commissioned officers at senior levels and non-commissioned personnel at operational levels. The apex is the Commissioner of Police, appointed by the President on government advice and responsible for overall command, assisted by Deputy Commissioners and Assistant Commissioners as stipulated in the Police Act. Gazetted officers, defined as those of Inspector rank or above, handle supervisory and investigative duties, while lower ranks focus on frontline enforcement.[56][41] The full rank order, from highest to lowest, comprises: Commissioner, Deputy Commissioner, Assistant Commissioner, Superintendent (including Senior Superintendent variants), Inspector, Sergeant Major (1st Class), Sergeant Major (2nd Class), Sergeant, and Constable. Promotions occur through performance evaluations, service length, and internal examinations, with salary scales aligned to public service grades—Constables starting at Scale 14 and advancing to Scale 11, Inspectors at Scale 8 progressing to Scale 6. No intermediate ranks like Corporal are formally delineated in standard structures.[21][57] Recruitment for entry-level Constables targets Maltese citizens aged 18–38 with Maltese and English proficiency, a clean criminal record, medical fitness, and minimum MQF Level 3 qualifications (e.g., four SEC/O-Level passes including languages). The selection process spans 4–8 months, encompassing application submission, initial screening, preliminary medical and physical efficiency tests, selective interviews, security vetting (including social media and associates), full medical examination, psychological assessment, and final interview before conditional appointment.[57] Selected recruits undergo a mandatory one-year full-time Pre-Tertiary Certificate in Policing (MQF/EQF Level 4) at the Academy for Disciplined Forces, effective from intakes starting October 2025, extending from prior six-month programs for enhanced accreditation by the University of Malta. The 750-hour curriculum includes 439 contact hours on topics such as evidence-based policing, ethics, legal frameworks, use of force, physical fitness, crime prevention, community engagement, investigation techniques, and report writing, assessed via exams (50% pass mark), practicals, and work placements. Successful graduates qualify as Constables, with ongoing in-service training for specialization or promotion. Higher-entry roles like Inspectors require an MQF Level 6 degree in fields such as law or criminology.[58][59][60][57]Facilities and Equipment

General Headquarters and Regional Stations

The Police General Headquarters is located at Pjazza San Kalcidonju, Floriana FRN 1530, Malta, serving as the central administrative, operational, and command hub for the Malta Police Force.[61] It houses key support functions including the Internal Audit and Investigations Unit, which oversees professional standards and disciplinary matters; the Investigations and Technical Support Division, encompassing forensic science, victim support, and crime prevention; and specialized branches such as Organised Crime, Cybersecurity, Counter-Terrorism, and International Relations.[5] Administrative units for human resources, ICT, finance, logistics, and strategy are also centralized here, facilitating coordination across the force's approximately 2,400 personnel as of 2020.[62] The Malta Police Force organizes its regional policing through a decentralized structure dividing Malta and Gozo into two regions—Region A and Region B—further segmented into 12 districts to enable localized enforcement, community engagement, and rapid response tailored to demographic and geographic needs.[63] Each region is led by an Assistant Commissioner responsible for district policing, with districts covering clusters of localities and featuring dedicated police stations or headquarters for routine operations, crime reporting, and patrols.[5] This framework, updated in February 2022 to align with contemporary urban growth and security challenges, assigns district officers familiar with local dynamics to enhance effectiveness.[64]| Region | Districts | Primary Coverage Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Region A (Southern and Central Malta) | 1 PD 2 PD 3 PD 4 PD 5 PD 6 PD | Valletta, Floriana Hamrun, Santa Venera, Pieta, Marsa Paola, Fgura, Santa Lucia, Tarxien, Luqa Bormla, Birgu, Isla, Kalkara, Xghajra, Zabbar, Marsaskala Zejtun, Birzebbuga, Marsaxlokk, Gudja, Ghaxaq, Mqabba, Kirkop, Safi, Zurrieq, Qrendi Qormi, Zebbug, Siggiewi |

| Region B (Northern Malta and Gozo) | 7 PD 8 PD 9 PD 10 PD 11 PD 12 PD | Sliema, Gzira, Ta’ Xbiex, Msida St. Julians, Pembroke, Swieqi, San Gwann Birkirkara, Balzan, Lija, Attard, Iklin, Naxxar, Gharghur Mosta, Mgarr, Rabat, Dingli, Mdina, Mtarfa St. Pauls Bay, Mellieha Gozo (all localities) |

Police Museum and Historical Artifacts

The Malta Police Museum, situated at the Police General Headquarters in Floriana, preserves artifacts and exhibits documenting the evolution of the force from its establishment in 1814 under British colonial rule.[66][67] The collection spans two primary rooms: one focused on the institutional history, featuring period-specific equipment, uniforms, badges, tools, and emblems used by officers over two centuries; the other dedicated to forensic reconstructions of notable murder cases, highlighting investigative techniques and crime scene artifacts.[68][69] Key historical artifacts include firearms such as machine guns, shotguns, and pistols from various eras, alongside clothing and operational gear that illustrate shifts in policing methods during the British protectorate, post-independence period, and modern times.[67][66] These items, drawn from the force's operational archives, provide tangible evidence of adaptations in law enforcement amid Malta's geopolitical changes, including the transition to sovereignty in 1964 and EU accession in 2004.[69] Early setup efforts for the museum received external support, such as contributions from cultural organizations in the 1990s, underscoring its role in public education on Maltese policing heritage.[70] In February 2024, the Malta Police Force entered a five-year memorandum of understanding with Heritage Malta to renovate and professionally manage the facility, transforming it into a modern interpretive center with enhanced preservation standards for its artifacts.[71][72] This initiative aims to digitize records, improve exhibit accessibility, and integrate advanced curatorial practices, ensuring long-term safeguarding of items like colonial-era proclamations and vintage vehicles while addressing prior limitations in space and display technology.[73] The museum also incorporates elements of a dedicated Crime Museum, showcasing case-specific relics to demonstrate forensic advancements.[74] Access remains geared toward educational visits, though public hours are limited and coordinated through headquarters.[68]Reforms and Modernization

Strategic Transformations (1996–2019)

The 1996 Modernisation Programme marked a pivotal shift for the Malta Police Force, aiming to reorient the organization towards community policing to enhance crime-fighting effectiveness and public accountability. Launched on 19 December 1996 by Prime Minister Alfred Sant, the initiative responded to criticisms of outdated practices and sought to decentralize operations, revise officer selection criteria, and introduce specialized training for community engagement. A Management Systems Unit report submitted on 6 January 1997 outlined 78 recommendations spanning legislation, strategy, internal controls, and operational procedures, emphasizing a broader police role in societal integration rather than reactive enforcement alone.[26] Implementation faced significant hurdles, including officer resistance rooted in entrenched organizational culture, high personnel turnover, and a top-down approach that eroded institutional identity. By 2002, the programme achieved partial success through structural reorganizations, such as improved decentralization and initial community outreach efforts, but persistent disengagement and incomplete cultural shifts limited deeper transformation. These challenges highlighted the difficulties of reforming a historically insular force, with outcomes including modest gains in public perception but ongoing needs for adaptive leadership.[26][75] Malta's accession to the European Union on 1 May 2004 necessitated further alignments in policing standards, including harmonization with EU acquis on human rights, data protection, and cross-border cooperation. This period saw incremental modernization via EU-funded initiatives, focusing on equipment upgrades, infrastructure enhancements, and advanced training programs to meet supranational requirements for professionalization and interoperability. For instance, investments supported specialized capabilities in areas like economic crime and border security, reflecting broader strategic adaptations to transnational threats without a singular comprehensive plan until later years.[28]Recent Strategies and Achievements (2020–2025 Onward)

In 2020, the Malta Police Force launched its Transformation Strategy 2020–2025, aimed at modernizing the organization into a flexible, efficient, data-driven, and community-centric entity while enhancing public trust, legitimacy, and responsiveness.[45] The strategy outlined 11 objectives and 49 initiatives, focusing on technological integration such as deployed case management systems, workflow tools, and human resources platforms; organizational restructuring to optimize workforce size and leadership frameworks; and strengthened community engagement through improved communication and feedback mechanisms.[45] These efforts emphasized anti-corruption measures, workforce diversity, and EU-funded professionalization to deliver a reliable, transparent service by 2025.[45] Key achievements under this strategy included sustained crime reductions, with 16,662 reported offences in 2024—a 1% decline from 2023 and a 35% per capita drop since 2004—alongside a 23% decrease in Gozo, marking the lowest theft levels in over 20 years.[6][30] Homicide investigations achieved a 100% clearance rate since 2018, with no unsolved cases.[6] Gender-based violence reporting rose 68% since 2020, reaching Malta's highest EU rate at 48.2%, supported by a dedicated unit.[6] Public trust metrics improved, with 90% confidence in 2022 surveys and the force ranked as Malta's most trusted institution per Eurobarometer data, outperforming the judiciary and media.[6][30] Operational enhancements encompassed nationwide community policing coverage, 95,042 hours of foot patrols, and 12,735 hours of e-bike patrols in 2024; expanded cyber crime capabilities with an Online Fraud Section; and the introduction of body-worn cameras, digital reporting, and AI tools via collaborations like the Malta Digital Innovation Authority.[30] Notable seizures included 1.5 tonnes of cocaine in 2022, the largest on record.[6] Governance reforms fully implemented 100% of National Audit Office recommendations by 2024, contributing to a global 10th ranking in order and security by the World Justice Project.[6] Building on these outcomes, the force introduced the Corporate Strategy 2025–2030 in September 2025, themed "Safer Communities, Smarter Policing," with three pillars: ensuring public safety and security, strengthening trust and legitimacy, and delivering smarter policing.[6] This framework expands to 15 priorities and 75 commitments—26 more than the prior strategy—prioritizing crime prevention through community partnerships, advanced technology adoption, officer wellness, and transparency metrics like ongoing public trust surveys and efficiency indicators.[6] Specialized advancements include a new Roads Policing Unit for traffic investigations and continued emphasis on proactive enforcement amid post-COVID crime stability below pre-pandemic levels.[30]Controversies and Criticisms

Internal Corruption and Fraud Cases

In February 2020, an investigation into the Malta Police Force's Traffic Section uncovered widespread overtime fraud following an anonymous whistleblower tip, resulting in the arrest of more than half of the unit's approximately 50 officers, including Superintendent Clint Camilleri.[76] The scheme involved falsified claims for unperformed overtime shifts, with officers allegedly logging hours for non-existent duties such as traffic management at construction sites.[77] Internal probes revealed directives from senior officers to delay or shelve evidence files related to the fraud, prompting further scrutiny of command accountability.[78] By mid-2020, charges of fraud and falsification of documents were filed against 32 traffic section officers in court, marking one of the largest internal disciplinary actions in the force's recent history.[79] Several defendants, including sergeants Matthew Azzopardi and Francis Larry Sciberras, were acquitted in subsequent trials, with courts citing insufficient evidence of direct complicity in the racket.[80] The case highlighted vulnerabilities in overtime verification processes but also exposed divisions within the force, as investigating officers reported pressure to minimize the probe's scope.[78] In January 2025, former Police Superintendent Ray Aquilina, who had headed the force's Financial Crime Investigation Department anti-money laundering unit, was charged with money laundering and corruption alongside businessman Yorgen Fenech, a figure linked to prior high-profile cases.[81] The charges stemmed from allegations of illicit financial transactions and abuse of office, though proceedings remain ongoing as of late 2025.[82] This incident underscored persistent risks of internal compromise in specialized units handling financial crimes, amid broader criticisms of oversight in the department.[83]Handling of High-Profile Investigations

The Malta Police Force's investigation into the October 16, 2017, assassination of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia exemplified both progress and profound shortcomings. Pre-assassination, the force failed to conduct formal risk assessments or provide sustained protection despite Caruana Galizia's repeated exposures of high-level corruption via the Panama Papers and Financial Intelligence Analysis Unit (FIAU) reports implicating figures like Keith Schembri and Konrad Mizzi, with protective patrols withdrawn after 2013 and no proactive probes into linked threats.[84] Post-assassination, initial delays, evidence mishandling (including lost mobile data), leaks to suspects, and ties between senior officers like Deputy Commissioner Silvio Valletta and prime suspect Yorgen Fenech compromised impartiality, amid understaffing in the Economic Crimes Unit and reliance on international aid from the FBI and Europol for breakthroughs.[84] A 2021 public inquiry attributed state responsibility for her death to these lapses, citing breaches of European Convention on Human Rights Article 2 obligations and a culture of impunity fostered by police inaction on financial crimes.[34] Arrests marked partial successes: the three alleged hitmen were apprehended in December 2017 based on forensic evidence, leading to convictions on June 6, 2025, while Fenech, identified as mastermind via pardoned middleman Melvin Theuma's testimony, was detained in November 2019 and charged with complicity, facing additional 2025 indictments for money laundering alongside former anti-money laundering unit head Ray Aquilina.[85][86] Police Commissioner Lawrence Cutajar resigned on January 17, 2020, amid public and official criticism of investigative inertia, though successors pursued leads with some vigor.[31] The inquiry recommended bolstering police independence, resources, ethical training, and protocols for at-risk journalists, including an Independent Police Complaints Board, yet implementation has lagged, perpetuating concerns over capacity for complex, politically sensitive probes.[84] In other high-profile cases, such as a July 2024 customs fraud and corruption probe involving six officers and operators, the force collaborated with the European Public Prosecutor's Office to secure charges against 11 suspects, demonstrating procedural competence in transnational financial crimes.[87] However, broader critiques persist regarding resource shortages and selective enforcement, with reports noting stalled inquiries into elite corruption and mafia-style killings since 2008, undermining public trust despite occasional successes like 15 arrests in a sophisticated money laundering ring.[88][89][90]Allegations of Political Influence and Resource Shortfalls

Allegations of political interference in the Malta Police Force have centered on high-profile investigations, particularly the 2017 assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia. In November 2019, international organizations including Reporters Without Borders expressed concern over apparent political interference in the probe, following the arrest of suspects linked to then-Prime Minister Joseph Muscat's inner circle.[91] A senior European monitor reported in October 2019 that Maltese police may have rejected key evidence in the case, raising questions about investigative integrity amid political pressures.[92] In December 2024, PEN International urged European leaders to hold Muscat accountable for alleged interference in the ongoing inquiry, highlighting persistent doubts about the force's autonomy.[93] Broader critiques have targeted the police commissioner's appointment process, with opposition calls in August 2024 for constitutional reforms to shield the role from executive influence, amid allegations of crimes with political dimensions.[94] A September 2023 report by the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) identified corruption among high-level politicians as a continuing concern, attributing weaknesses in Malta's law enforcement to insufficient safeguards against undue influence.[88] The force has denied specific interference claims, such as in the 2024 Vitals Global Healthcare scandal, asserting independent operations without external pressure.[95] Internal testimony from investigators, including Magistrate Alexandra Mamo in November 2021, has affirmed no direct political meddling in sensitive cases, though external pressures on prominent figures were acknowledged.[96] Resource shortfalls have compounded these issues, with the police force facing chronic understaffing and high resignation rates. By March 2024, resignations had surged, leaving the force "severely undermined by a lack of resources, including expert and dedicated investigative capabilities," per GRECO assessments.[97] The Financial Crimes Investigation Department lost about 20% of its officers between 2020 and 2022 due to resignations and reassignments, disrupting complex probes.[98] Nationalist MP Alex Borg warned in June 2022 that human resource shortages—exacerbated by low salaries—were causing public safety incidents, with citizens bearing the consequences.[99] In July 2022, opposition figures held Police Commissioner Angelo Gafa and Home Affairs Minister Byron Camilleri accountable for mishaps linked to personnel deficits, including inadequate coverage in high-crime areas.[100] By July 2025, low pay was flagged as a national security risk, prompting calls for salary hikes to retain talent amid reliance on foreign recruits to fill gaps.[101] The force's 2025 corporate strategy acknowledged limited human resources, prioritizing efficient allocation but highlighting strains on core duties like enforcement and investigations.[102] These deficits have been cited as hindering effective responses to organized crime and corruption, with ratios in urban areas like Sliema reaching one officer per 700 residents by 2024.[103]Leadership

Police Commissioners and Tenure

The Commissioner of Police heads the Malta Police Force and is responsible for its overall command, operations, and administration.[41] The position, established in 1814, has seen numerous incumbents, with appointments historically influenced by colonial authorities and, post-independence in 1964, by the Maltese government, often leading to short tenures amid political pressures or scandals. [23] The following table enumerates Police Commissioners from 1955 onward, including appointment and end dates where available, drawn from documented historical accounts.[23]| Name | Appointment Date | End of Tenure Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| George Cachia | November 1954 | June 1956 | Retired after inquiry-related issues. |

| Vivian De Gray | June 1, 1956 | May 1972 | Retired following clashes with Prime Minister Mintoff. |

| Alfred Bencini | May 1972 | January 1973 | Resigned after internal conflicts. |

| Edward Bencini | January 1973 | January 1974 | Retired at age 60. |

| Enoch Tonna | 1974 | September 9, 1977 | Asked to resign. |

| John Cachia | September 9, 1977 | March 28, 1980 | Retired. |

| Lawrence Pullicino | March 3, 1980 | November 1987 | Compulsorily retired on public interest grounds. |

| Alfred Calleja | April 4, 1988 | November 1, 1992 | Retired; tenure reportedly involuntary. |

| George Grech | November 1992 | October 30, 2001 | Resigned due to sex scandal. |

| John Rizzo | November 2, 2001 | April 13, 2013 | Stepped down after political change. |

| Peter Paul Zammit | April 13, 2013 | July 2014 | Stepped down after one year. |

| Raymond Zammit | July 2014 | December 9, 2014 | Resigned. |

| Michael Cassar | December 9, 2014 | April 27, 2016 | End of tenure. |

| Lawrence Cutajar | April 27, 2016 | January 17, 2020 | Resigned amid criticism over high-profile investigations.[104] |

| Carmelo Magri (acting) | January 17, 2020 | June 2020 | Interim leadership.[105] |

| Angelo Gafà | June 23, 2020 | Incumbent (as of 2025) | Appointed for four-year term, renewed in June 2024 for second term ending 2028.[41] [106] |