Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Monody

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (September 2018) |

In music, monody refers to a solo vocal style distinguished by having a single melodic line and instrumental accompaniment. Although such music is found in various cultures throughout history, the term is specifically applied to Italian song of the early 17th century, particularly the period from about 1600 to 1640. The term is used both for the style and for individual songs (so one can speak both of monody as a whole as well as a particular monody). The term itself is a recent invention of scholars. No composer of the 17th century ever called a piece a monody. Compositions in monodic form might be called madrigals, motets, or even concertos (in the earlier sense of stile concertato, meaning "with instruments").

In poetry, the term monody has become specialized to refer to a poem in which one person laments another's death. (In the context of ancient Greek literature, monody, μονῳδία, could simply refer to lyric poetry sung by a single performer, rather than by a chorus.)

History

[edit]Musical monody, which developed out of an attempt by the Florentine Camerata in the 1580s to restore ancient Greek practices of melody and declamation (probably with little historical accuracy), one solo voice sings a melodic part, usually with considerable ornamentation, over a rhythmically independent bass line. Accompanying instruments could be lute, chitarrone, theorbo, harpsichord, organ, and even on occasion guitar. While some monodies were arrangements for smaller forces of the music for large ensembles which was common at the end of the 16th century, especially in the Venetian School, most monodies were composed independently. The development of monody was one of the defining characteristics of early Baroque practice, as opposed to late Renaissance style, in which groups of voices sang independently and with a greater balance between parts.

Contrasting passages in monodies could be for the most part melodic or for the most part declamatory and the two styles of presentation developed into the aria and the recitative respectively, both of which came to be incorporated into the cantata by about 1635.

The parallel development of solo song with accompaniment in France was called the air de cour: the term monody is not normally applied to these more conservative songs, however, which retained many musical characteristics of the Renaissance chanson.

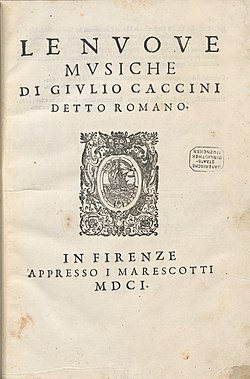

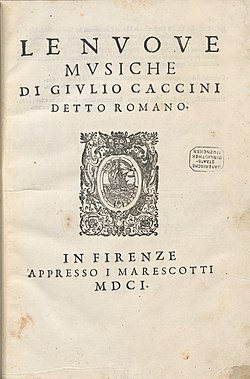

An important early treatise on monody is contained in Giulio Caccini's song collection, Le nuove musiche (Florence, 1601).

Main composers

[edit]- Vincenzo Galilei (1520 – 1591)

- Giulio Caccini (c. 1545 – 1618)

- Emilio de' Cavalieri (c. 1550 – 1602)

- Lucia Quinciani (b. c. 1566)

- Bartolomeo Barbarino (c. 1568 – c. 1617)

- Jacopo Peri (1561 – 1633)

- Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643)

- Alessandro Grandi (c. 1575 – 1630)

- Giovanni Pietro Berti (d. 1638)

- Sigismondo d'India (c. 1582 – 1629)

- Claudio Saracini (1586 – c. 1649)

- Francesca Caccini (1587 – after 1641)

- Benedetto Ferrari (c. 1603 – 1681)

See also

[edit]References and further reading

[edit]- Nigel Fortune, "Monody", in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. 20 vol. London, Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1980. ISBN 1-56159-174-2

- Gustave Reese, Music in the Renaissance. New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1954. ISBN 0-393-09530-4

- Manfred Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1947. ISBN 0-393-09745-5