Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Singing

View on Wikipedia

Singing is the art of creating music with the voice. It is the oldest form of musical expression, and the human voice can be considered the first musical instrument.[1] The definition of singing varies across sources.[1] Some sources define singing as the act of creating musical sounds with the voice.[2][3][4] Other common definitions include "the utterance of words or sounds in tuneful succession"[1] or "the production of musical tones by means of the human voice".[5]

A person whose profession (or hobby) is singing is called a singer or a vocalist (in jazz or popular music).[6][7] Singers perform music (arias, recitatives, songs, etc.) that can be sung with or without accompaniment by musical instruments. Singing is often done in an ensemble of musicians, such as a choir. Singers may perform as soloists or accompanied by anything from a single instrument (as in art songs or some jazz styles) up to a symphony orchestra or big band. Many styles of singing exist throughout the world.

Singing can be formal or informal, arranged, or improvised. It may be done as a form of religious devotion, as a hobby, as a source of pleasure, comfort, as part of a ritual, during music education or as a profession. Excellence in singing requires time, dedication, instruction, and regular practice. If practice is done regularly then the sounds can become clearer and stronger.[8] Professional singers usually build their careers around one specific musical genre, such as classical or rock, although there are singers with crossover success (singing in more than one genre). Professional singers typically receive voice training from vocal coaches or voice teachers throughout their careers.

Singing should not be confused with rapping as they are not the same.[9][10][11] According to music scholar and rap historian Martin E. Connor, "Rap is often defined by its very opposition to singing."[12] While also a form of vocal music, rap differs from singing in that it does not engage with tonality in the same way and does not require pitch accuracy.[10] Like singing, rap does use rhythm in connection to words but these are spoken rather than sung on specific pitches.[10] Grove Music Online states that "Within the historical context of popular music in the United States, rap can be seen as an alternative to singing that could connect directly with stylistic speech practices in African American English."[9] However, some rap artists do employ singing as well as rapping in their music; using the switch between the rhythmic speech of rapping and the sung pitches of singing as a striking contrast to grab the attention of the listener.[13]

Voices

[edit]

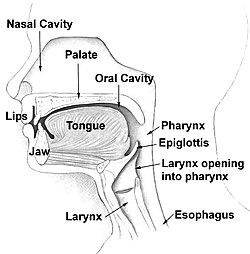

In its physical aspect, singing has a well-defined technique that depends on the use of the lungs, which act as an air supply or bellows; on the larynx, which acts as a reed or vibrator; on the chest, head cavities and the skeleton, which have the function of an amplifier, as the tube in a wind instrument; and on the tongue, which together with the palate, teeth, and lips articulate and impose consonants and vowels on the amplified sound. Though these four mechanisms function independently, they are nevertheless coordinated in the establishment of a vocal technique and are made to interact upon one another.[14] During passive breathing, air is inhaled with the diaphragm while exhalation occurs without any effort. Exhalation may be aided by the abdominal, internal intercostal and lower pelvis/pelvic muscles. Inhalation is aided by use of external intercostals, scalenes, and sternocleidomastoid muscles. The pitch is altered with the vocal cords. With the lips closed, this is called humming.

The sound of each individual's singing voice is entirely unique not only because of the actual shape and size of an individual's vocal cords, but also due to the size and shape of the rest of that person's body. Humans have vocal folds which can loosen, tighten, or change their thickness, and over which breath can be transferred at varying pressures. The shape of the chest and neck, the position of the tongue, and the tightness of otherwise unrelated muscles can be altered. Any one of these actions results in a change in pitch, volume (loudness), timbre, or tone of the sound produced. Sound also resonates within different parts of the body and an individual's size and bone structure can affect the sound produced by an individual.

Singers can also learn to project sound in certain ways so that it resonates better within their vocal tract. This is known as vocal resonation. Another major influence on vocal sound and production is the function of the larynx which people can manipulate in different ways to produce different sounds. These different kinds of laryngeal function are described as different kinds of vocal registers.[15] The primary method for singers to accomplish this is through the use of the singer's formant; which has been shown to match particularly well to the most sensitive part of the ear's frequency range.[16][17]

It has also been shown that a more powerful voice may be achieved with a fatter and fluid-like vocal fold mucosa.[18][19] The more pliable the mucosa, the more efficient the transfer of energy from the airflow to the vocal folds.[20]

Vocal classification

[edit]| Voice type |

|---|

| Female |

| Male |

In European classical music and opera, voices are treated like musical instruments. Composers who write vocal music must have an understanding of the skills, talents, and vocal properties of singers. Voice classification is the process by which human singing voices are evaluated and are thereby designated into voice types. These qualities include but are not limited to vocal range, vocal weight, vocal tessitura, vocal timbre, and vocal transition points such as breaks and lifts within the voice. Other considerations are physical characteristics, speech level, scientific testing, and vocal registration.[21] The science behind voice classification developed within European classical music has been slow in adapting to more modern forms of singing. Voice classification is often used within opera to associate possible roles with potential voices. There are currently several different systems in use within classical music including the German Fach system and the choral music system among many others. No system is universally applied or accepted.[22]

However, most classical music systems acknowledge seven different major voice categories. Women are typically divided into three groups: soprano, mezzo-soprano, and contralto. Men are usually divided into four groups: countertenor, tenor, baritone, and bass. With regard to voices of pre-pubescent children, an eighth term, treble, can be applied. Within each of these major categories, several sub-categories identify specific vocal qualities like coloratura facility and vocal weight to differentiate between voices.[23]

Within choral music, singers' voices are divided solely on the basis of vocal range. Choral music most commonly divides vocal parts into high and low voices within each sex (SATB, or soprano, alto, tenor, and bass). As a result, the typical choral situation gives many opportunities for misclassification to occur.[23] Since most people have medium voices, they must be assigned to a part that is either too high or too low for them; the mezzo-soprano must sing soprano or alto and the baritone must sing tenor or bass. Either option can present problems for the singer, but for most singers, there are fewer dangers in singing too low than in singing too high.[24]

Within contemporary forms of music (sometimes referred to as contemporary commercial music), singers are classified by the style of music they sing, such as jazz, pop, blues, soul, country, folk, and rock styles. There is currently no authoritative voice classification system within non-classical music. Attempts have been made to adopt classical voice type terms to other forms of singing but such attempts have been met with controversy.[25] The development of voice categorizations were made with the understanding that the singer would be using classical vocal technique within a specified range using unamplified (no microphones) vocal production. Since contemporary musicians use different vocal techniques and microphones and are not forced to fit into a specific vocal role, applying such terms as soprano, tenor, baritone, etc. can be misleading or even inaccurate.[26]

Vocal registration

[edit]| Vocal registers |

|---|

| HighestLowest |

Vocal registration refers to the system of vocal registers within the voice. A register in the voice is a particular series of tones, produced in the same vibratory pattern of the vocal folds, and possessing the same quality. Registers originate in laryngeal function. They occur because the vocal folds are capable of producing several different vibratory patterns.[27] Each of these vibratory patterns appears within a particular range of pitches and produces certain characteristic sounds.[28] The occurrence of registers has also been attributed to the effects of the acoustic interaction between the vocal fold oscillation and the vocal tract.[29] The term "register" can be somewhat confusing as it encompasses several aspects of the voice. The term register can be used to refer to any of the following:[23]

- A particular part of the vocal range such as the upper, middle, or lower registers.

- A resonance area such as chest voice or head voice.

- A phonatory process (phonation is the process of producing vocal sound by the vibration of the vocal folds that is in turn modified by the resonance of the vocal tract)

- A certain vocal timbre or vocal "color"

- A region of the voice which is defined or delimited by vocal breaks.

In linguistics, a register language is a language which combines tone and vowel phonation into a single phonological system. Within speech pathology, the term vocal register has three constituent elements: a certain vibratory pattern of the vocal folds, a certain series of pitches, and a certain type of sound. Speech pathologists identify four vocal registers based on the physiology of laryngeal function: the vocal fry register, the modal register, the falsetto register, and the whistle register. This view is also adopted by many vocal pedagogues.[23]

Vocal resonation

[edit]

Vocal resonation is the process by which the basic product of phonation is enhanced in timbre or intensity by the air-filled cavities through which it passes on its way to the outside air. Various terms related to the resonation process include amplification, enrichment, enlargement, improvement, intensification, and prolongation, although in strictly scientific usage acoustic authorities would question most of them. The main point to be drawn from these terms by a singer or speaker is that the result of resonation is, or should be, to make a better sound.[23] There are seven areas that may be listed as possible vocal resonators. In sequence from the lowest within the body to the highest, these areas are the chest, the tracheal tree, the larynx itself, the pharynx, the oral cavity, the nasal cavity, and the sinuses.[30]

Chest voice and head voice

[edit]Chest voice and head voice are terms used within vocal music. The use of these terms varies widely within vocal pedagogical circles and there is currently no one consistent opinion among vocal music professionals in regards to these terms. Chest voice can be used in relation to a particular part of the vocal range or type of vocal register; a vocal resonance area; or a specific vocal timbre.[23] Head voice can be used in relation to a particular part of the vocal range or type of vocal register or a vocal resonance area.[23] In Men, the head voice is commonly referred to as the falsetto. The transition from and combination of chest voice and head voice is referred to as vocal mix or vocal mixing in the singer's performance.[31] Vocal mixing can be inflected in specific modalities of artists who may concentrate on smooth transitions between chest voice and head voice, and those who may use a "flip"[32] to describe the sudden transition from chest voice to head voice for artistic reasons and enhancement of vocal performances.

History and development

[edit]The first recorded mention of the terms chest voice and head voice was around the 13th century when it was distinguished from the "throat voice" (pectoris, guttoris, capitis—at this time it is likely that head voice referred to the falsetto register) by the writers Johannes de Garlandia and Jerome of Moravia.[33] The terms were later adopted within bel canto, the Italian opera singing method, where chest voice was identified as the lowest and head voice the highest of three vocal registers: the chest, passagio, and head registers.[22] This approach is still taught by some vocal pedagogists today. Another current popular approach that is based on the bel canto model is to divide both men and women's voices into three registers. Men's voices are divided into "chest register", "head register", and "falsetto register" and woman's voices into "chest register", "middle register", and "head register". Such pedagogists teach that the head register is a vocal technique used in singing to describe the resonance felt in the singer's head.[34]

However, as knowledge of physiology has increased over the past two hundred years, so has the understanding of the physical process of singing and vocal production. As a result, many vocal pedagogists, such as Ralph Appelman at Indiana University and William Vennard at the University of Southern California, have redefined or even abandoned the use of the terms chest voice and head voice.[22] In particular, the use of the terms chest register and head register have become controversial since vocal registration is more commonly seen today as a product of laryngeal function that is unrelated to the physiology of the chest, lungs, and head. For this reason, many vocal pedagogists argue that it is meaningless to speak of registers being produced in the chest or head. They argue that the vibratory sensations which are felt in these areas are resonance phenomena and should be described in terms related to vocal resonance, not to registers. These vocal pedagogists prefer the terms chest voice and head voice over the term register. This view believes that the problems which people identify as register problems are really problems of resonance adjustment. This view is also in alignment with the views of other academic fields that study vocal registration including speech pathology, phonetics, and linguistics. Although both methods are still in use, current vocal pedagogical practice tends to adopt the newer more scientific view. Also, some vocal pedagogists take ideas from both viewpoints.[23]

The contemporary use of the term chest voice often refers to a specific kind of vocal coloration or vocal timbre. In classical singing, its use is limited entirely to the lower part of the modal register or normal voice. Within other forms of singing, chest voice is often applied throughout the modal register. Chest timbre can add a wonderful array of sounds to a singer's vocal interpretive palette.[35] However, the use of an overly strong chest voice in the higher registers in an attempt to hit higher notes in the chest can lead to forcing. Forcing can lead consequently to vocal deterioration.[36]

Vocal registers: General discussion of transitions

[edit]Passaggio (Italian pronunciation: [pasˈsaddʒo]) is a term used in classical singing to describe the transition area between the vocal registers. The passaggi (plural) of the voice lie between the different vocal registers, such as the chest voice, where any singer can produce a powerful sound, the middle voice, and the head voice, where a penetrating sound is accessible, but usually only through vocal training. The historic Italian school of singing describes a primo passaggio and a secondo passaggio connected through a zona di passaggio in the male voice and a primo passaggio and secondo passaggio in the female voice. A major goal of classical voice training in classical styles is to maintain an even timbre throughout the passaggio. Through proper training, it is possible to produce a resonant and powerful sound.

Vocal registers and transitions

[edit]One cannot adequately discuss the vocal passaggio without having a basic understanding of the different vocal registers. In his book The Principles of Voice Production, Ingo Titze states, "The term register has been used to describe perceptually distinct regions of vocal quality that can be maintained over some ranges of pitch and loudness."[37] Discrepancies in terminology exist between different fields of vocal study, such as teachers and singers, researchers, and clinicians. As Marilee David points out, "Voice scientists see registration primarily as acoustic events."[38] For singers, it is more common to explain registration events based on the physical sensations they feel when singing. Titze also explains that there are discrepancies in the terminology used to talk about vocal registration between speech pathologists and singing teachers.[39] Since this article discusses the passaggio, which is a term used by classical singers, the registers will be discussed as they are in the field of singing rather than speech pathology and science.

The three main registers, described as head, middle (mixed), and chest voice, are described as having a rich timbre, because of the overtones due to the sympathetic resonance within the human body. Their names are derived from the area in which the singer feels these resonant vibration in the body. The chest register, more commonly referred to as the chest voice, is the lowest of the registers. When singing in the chest voice the singer feels sympathetic vibration in the chest. This is the register that people most commonly use while speaking. The middle voice falls in between the chest voice and head voice. The head register, or the head voice, is the highest of the main vocal registers. When singing in the head voice, the singer may feel sympathetic vibration occurring in the face or another part of the head. Where these registers lie in the voice is dependent on sex and the voice type within each sex.[40]

There are an additional two registers called falsetto and flageolet register, which lie above their head register.[41][42] Training is often required to access the pitches within these registers. Men and women with lower voices rarely sing in these registers. Lower-voiced women in particular receive very little if any training in the flageolet register. Men have one more additional register called the strohbass, which lies below the chest voice. Singing in this register is hard on the vocal cords, and therefore, is hardly ever used.[43]

Vocal pedagogy

[edit]

Vocal pedagogy is the study of the teaching of singing. The art and science of vocal pedagogy has a long history that began in Ancient Greece[44] and continues to develop and change today. Professions that practice the art and science of vocal pedagogy include vocal coaches, choral directors, vocal music educators, opera directors, and other teachers of singing.

Vocal pedagogy concepts are a part of developing proper vocal technique. Typical areas of study include the following:[45][46]

- Anatomy and physiology as it relates to the physical process of singing

- Vocal health and voice disorders related to singing

- Breathing and air support for singing

- Phonation

- Vocal resonation or Voice projection

- Vocal registration: a particular series of tones, produced in the same vibratory pattern of the vocal folds, and possessing the same quality, which originate in laryngeal function, because each of these vibratory patterns appears within a particular range of pitches and produces certain characteristic sounds.

- Voice classification

- Vocal styles: for classical singers, this includes styles ranging from Lieder to opera; for pop singers, styles can include "belted out" a blues ballads; for jazz singers, styles can include Swing ballads and scatting.

- Techniques used in styles such as sostenuto and legato, range extension, tone quality, vibrato, and coloratura

Vocal technique

[edit]Singing when done with proper vocal technique is an integrated and coordinated act that effectively coordinates the physical processes of singing. There are four physical processes involved in producing vocal sound: respiration, phonation, resonation, and articulation. These processes occur in the following sequence:

- Breath is taken

- Sound is initiated in the larynx

- The vocal resonators receive the sound and influence it

- The articulators shape the sound into recognizable units

Although these four processes are often considered separately when studied, in actual practice, they merge into one coordinated function. With an effective singer or speaker, one should rarely be reminded of the process involved as their mind and body are so coordinated that one only perceives the resulting unified function. Many vocal problems result from a lack of coordination within this process.[26]

Since singing is a coordinated act, it is difficult to discuss any of the individual technical areas and processes without relating them to others. For example, phonation only comes into perspective when it is connected with respiration; the articulators affect resonance; the resonators affect the vocal folds; the vocal folds affect breath control; and so forth. Vocal problems are often a result of a breakdown in one part of this coordinated process which causes voice teachers to frequently focus intensively on one area of the process with their student until that issue is resolved. However, some areas of the art of singing are so much the result of coordinated functions that it is hard to discuss them under a traditional heading like phonation, resonation, articulation, or respiration.

Once the voice student has become aware of the physical processes that make up the act of singing and of how those processes function, the student begins the task of trying to coordinate them. Inevitably, students and teachers will become more concerned with one area of the technique than another. The various processes may progress at different rates, with a resulting imbalance or lack of coordination. The areas of vocal technique which seem to depend most strongly on the student's ability to coordinate various functions are:[23]

- Extending the vocal range to its maximum potential

- Developing consistent vocal production with a consistent tone quality

- Developing flexibility and agility

- Achieving a balanced vibrato

- A blend of chest and head voice on every note of the range[47]

Developing the singing voice

[edit]Singing is a skill that requires highly developed muscle reflexes. Singing does not require much muscle strength but it does require a high degree of muscle coordination. Individuals can develop their voices further through the careful and systematic practice of both songs and vocal exercises. Vocal exercises have several purposes, including[23] warming up the voice; extending the vocal range; "lining up" the voice horizontally and vertically; and acquiring vocal techniques such as legato, staccato, control of dynamics, rapid figurations, learning to sing wide intervals comfortably, singing trills, singing melismas and correcting vocal faults.

Vocal pedagogists instruct their students to exercise their voices in an intelligent manner. Singers should be thinking constantly about the kind of sound they are making and the kind of sensations they are feeling while they are singing.[26]

Learning to sing is an activity that benefits from the involvement of an instructor. A singer does not hear the same sounds inside their head that others hear outside. Therefore, having a guide who can tell a student what kinds of sounds he or she is producing guides a singer to understand which of the internal sounds correspond to the desired sounds required by the style of singing the student aims to re-create.[citation needed]

Extending vocal range

[edit]An important goal of vocal development is to learn to sing to the natural limits[48] of one's vocal range without any obvious or distracting changes of quality or technique. Vocal pedagogists teach that a singer can only achieve this goal when all of the physical processes involved in singing (such as laryngeal action, breath support, resonance adjustment, and articulatory movement) are effectively working together. Most vocal pedagogists believe in coordinating these processes by (1) establishing good vocal habits in the most comfortable tessitura of the voice, and then (2) slowly expanding the range.[15]

There are three factors that significantly affect the ability to sing higher or lower:

- The energy factor – "energy" has several connotations. It refers to the total response of the body to the making of sound; to a dynamic relationship between the breathing-in muscles and the breathing-out muscles known as the breath support mechanism; to the amount of breath pressure delivered to the vocal folds and their resistance to that pressure; and to the dynamic level of the sound.

- The space factor – "space" refers to the size of the inside of the mouth and the position of the palate and larynx. Generally speaking, a singer's mouth should be opened wider the higher he or she sings. The internal space or position of the soft palate and larynx can be widened by relaxing the throat. Vocal pedagogists describe this as feeling like the "beginning of a yawn".

- The depth factor – "depth" has two connotations. It refers to the actual physical sensations of depth in the body and vocal mechanism, and to mental concepts of depth that are related to tone quality.

McKinney says, "These three factors can be expressed in three basic rules: (1) As you sing higher, you must use more energy; as you sing lower, you must use less. (2) As you sing higher, you must use more space; as you sing lower, you must use less. (3) As you sing higher, you must use more depth; as you sing lower, you must use less."[23]

Posture

[edit]The singing process functions best when certain physical conditions of the body are put in place. The ability to move air in and out of the body freely and to obtain the needed quantity of air can be seriously affected by the posture of the various parts of the breathing mechanism. A sunken chest position will limit the capacity of the lungs, and a tense abdominal wall will inhibit the downward travel of the diaphragm. Good posture allows the breathing mechanism to fulfill its basic function efficiently without any undue expenditure of energy. Good posture also makes it easier to initiate phonation and to tune the resonators as proper alignment prevents unnecessary tension in the body. Vocal pedagogists have also noted that when singers assume good posture it often provides them with a greater sense of self-assurance and poise while performing. Audiences also tend to respond better to singers with good posture. Habitual good posture also ultimately improves the overall health of the body by enabling better blood circulation and preventing fatigue and stress on the body.[15]

Good singing posture typically involves an aligned spine, relaxed shoulders, and balanced stance to allow for optimal breath support and resonance. There are eight components of the ideal singing posture:

- Feet slightly apart

- Legs straight but knees slightly bent

- Hips facing straight forward

- Spine aligned

- Abdomen flat

- Chest comfortably forward

- Shoulders down and back

- Head facing straight forward

Breathing and breath support

[edit]Natural breathing has three stages: a breathing-in period, breathing out period, and a resting or recovery period; these stages are not usually consciously controlled. Within singing, there are four stages of breathing: a breathing-in period (inhalation); a setting up controls period (suspension); a controlled exhalation period (phonation); and a recovery period.

These stages must be under conscious control by the singer until they become conditioned reflexes. Many singers abandon conscious controls before their reflexes are fully conditioned which ultimately leads to chronic vocal problems.[49]

Vibrato

[edit]Vibrato is a technique in which a sustained note wavers very quickly and consistently between a higher and a lower pitch, giving the note a slight quaver. Vibrato is the pulse or wave in a sustained tone. Vibrato occurs naturally and is the result of proper breath support and a relaxed vocal apparatus.[50] Some studies have shown that vibrato is the result of a neuromuscular tremor in the vocal folds. In 1922 Max Schoen was the first to make the comparison of vibrato to a tremor due to change in amplitude, lack of automatic control and it being half the rate of normal muscular discharge.[51] Vibrato is commonly used in classical, jazz, and popular singing styles as a means of expression, often contributing to a richer tone quality.

Extended vocal technique

[edit]Extended vocal techniques include rapping, screaming, growling, overtones, sliding, falsetto, yodeling, belting, use of vocal fry register, using sound reinforcement systems, among others. A sound reinforcement system is the combination of microphones, signal processors, amplifiers, and loudspeakers. The combination of such units may also use reverb, echo chambers and Auto-Tune among other devices.

Vocal music

[edit]Vocal music is music performed by one or more singers, which are typically called songs, and which may be performed with or without instrumental accompaniment, in which singing provides the main focus of the piece. Vocal music is probably the oldest form of music since it does not require any instrument or equipment besides the voice. All musical cultures have some form of vocal music and there are many long-standing singing traditions throughout the world's cultures. Music which employs singing but does not feature it prominently is generally considered instrumental music. For example, some blues rock songs may have a short, simple call-and-response chorus, but the emphasis in the song is on the instrumental melodies and improvisation. Vocal music typically features sung words called lyrics, although there are notable examples of vocal music that are performed using non-linguistic syllables or noises, sometimes as musical onomatopoeia. A short piece of vocal music with lyrics is broadly termed a song, although, in classical music, terms such as aria are typically used.

Genres of vocal music

[edit]

Vocal music is written in many different forms and styles which are often labeled within a particular genre of music. These genres include popular music, art music, religious music, secular music, and fusions of such genres. Within these larger genres are many subgenres. For example, popular music would encompass blues, jazz, country music, easy listening, hip hop, rock music, and several other genres. There may also be a subgenre within a subgenre such as vocalese and scat singing in jazz.

Popular and traditional music

[edit]In many modern pop musical groups, a lead singer performs the primary vocals or melody of a song, as opposed to a backing singer who sings backup vocals or the harmony of a song. Backing vocalists sing some, but usually, not all, parts of the song often singing only in a song's refrain or humming in the background. An exception is five-part gospel a cappella music, where the lead is the highest of the five voices and sings a descant and not the melody. Some artists may sing both the lead and backing vocals on audio recordings by overlapping recorded vocal tracks.

Popular music includes a range of vocal styles. Hip hop uses rapping, the rhythmic delivery of rhymes in a rhythmic speech over a beat or without accompaniment. Some types of rapping consist mostly or entirely of speech and chanting, like the Jamaican "toasting". In some types of rapping, the performers may interpolate short sung or half-sung passages. Blues singing is based on the use of the blue notes – notes sung at a slightly lower pitch than that of the major scale for expressive purposes. In heavy metal and hardcore punk subgenres, vocal styles can include techniques such as screams, shouts, and unusual sounds such as the "death growl".

One difference between live performances in the popular and Classical genres is that whereas Classical performers often sing without amplification in small- to mid-size halls, in popular music, a microphone and PA system (amplifier and speakers) are used in almost all performance venues, even a small coffee house. The use of the microphone has had several impacts on popular music. For one, it facilitated the development of intimate, expressive singing styles such as "crooning" which would not have enough projection and volume if done without a microphone. As well, pop singers who use microphones can do a range of other vocal styles that would not project without amplification, such as making whispering sounds, humming, and mixing half-sung and sung tones. As well, some performers use the microphone's response patterns to create effects, such as bringing the mic very close to the mouth to get an enhanced bass response, or, in the case of hip-hop beatboxers, doing plosive "p" and "b" sounds into the mic to create percussive effects. In the 2000s, controversy arose over the widespread use of electronic Auto-Tune pitch correction devices with recorded and live popular music vocals. Controversy has also arisen due to cases where pop singers have been found to be lip-syncing to a pre-recorded recording of their vocal performance or, in the case of the controversial act Milli Vanilli, lip-syncing to tracks recorded by other uncredited singers.

While some bands use backup singers who only sing when they are on stage, it is common for backup singers in popular music to have other roles. In many rock and metal bands, the musicians doing backup vocals also play instruments, such as rhythm guitar, electric bass, or drums. In Latin or Afro-Cuban groups, backup singers may play percussion instruments or shakers while singing. In some pop and hip hop groups and in musical theater, the backup singers may be required to perform elaborately choreographed dance routines while they sing through headset microphones.

Careers

[edit]The salaries and working conditions for vocalists vary a great deal. While jobs in other music fields such as music education choir conductors tend to be based on full-time, salaried positions, singing jobs tend to be based on contracts for individual shows or performances, or for a sequence of shows.

Aspiring singers and vocalists must have musical skills, an excellent voice, the ability to work with people, and a sense of showmanship and drama. Additionally, singers need to have the ambition and drive to continually study and improve.[52]

Professional singers continue to seek out vocal coaching to hone their skills, extend their range, and learn new styles. As well, aspiring singers need to gain specialized skills in the vocal techniques used to interpret songs, learn about the vocal literature from their chosen style of music, and gain skills in choral music techniques, sight singing and memorizing songs, and vocal exercises.

Some singers learn other music related jobs, such as composing, music producing and songwriting. Some singers put videos on YouTube and streaming apps. Singers market themselves to buyers of vocal talent, by doing auditions in front of a music director. Depending on the style of vocal music that a person has trained in, the "talent buyers" that they seek out may be record company, A&R representatives, music directors, choir directors, nightclub managers, or concert promoters. A CD or DVD with excerpts of vocal performances is used to demonstrate a singer's skills. Some singers hire an agent or manager to help them to seek out paid engagements and other performance opportunities; the agent or manager is often paid by receiving a percentage of the fees that the singer gets from performing onstage.

Singing competitions

[edit]There are several television shows that showcase singing. Since the 1990s, televised singing competitions such as Sa Re Ga Ma Pa (India), American Idol (US), and The Voice (international franchise) have become popular formats for discovering and promoting vocal talent.. American Idol was launched in 2002. The first singing reality show was Sa Re Ga Ma Pa launched by Zee TV in 1995.[53] At the American Idol Contestants audition in front of a panel of judges to see if they can move on to the next round in Hollywood, from then, the competition begins. The field of contestants is narrowed down week by week until a winner is chosen. To move on to the next round, the contestants' fate is determined by a vote by viewers. The Voice is another singing competition program. Similar to American Idol, the contestants audition in front of a panel of judges, however, the judges' chairs are faced towards the audience during the performance. If the coaches are interested in the artist, they will press their button signifying they want to coach them. Once the auditions conclude, coaches have their team of artists and the competition begins. Coaches then mentor their artists and they compete to find the best singer. Other well-known singing competitions include The X Factor, America's Got Talent, Rising Star and The Sing-Off.

A different example of a singing competition is Don't Forget the Lyrics!, where the show's contestants compete to win cash prizes by correctly recalling song lyrics from a variety of genres. The show contrasts to many other music-based game shows in that artistic talent (such as the ability to sing or dance in an aesthetically pleasing way) is irrelevant to the contestants' chances of winning; in the words of one of their commercials prior to the first airing, "You don't have to sing it well; you just have to sing it right." In a similar vein, The Singing Bee combines karaoke singing with a spelling bee-style competition, with the show featuring contestants trying to remember the lyrics to popular songs.

Singing and language

[edit]Every spoken language, natural or non-natural language has its own intrinsic musicality which affects singing by means of pitch, phrasing, and accent.

American Sign Language: Artistic Song Signing

[edit]An artistic signer, a signer who translates the lyrics of a song into American Sign Language (ASL), can modify existing signs, create new signs from the three basic parameters of sign language, and manipulate the typical signing space, thus deliberately expressing "rhythm, pitch, phrasing, and timbre."[54] Moreover, an artistic signer can be a person who is "Deaf, hearing, or hard of hearing" such as Justina Miles, a Deaf performer who used ASL to interpret Rihanna's 2023 Super Bowl Halftime Show performance, and Stephen Torrence, a hearing person who created signed songs on YouTube.[54][55]

Neurological aspects

[edit]Much research has been done recently on the link between music and language, especially singing. It is becoming increasingly clear that these two processes are very much alike, and yet also different. Levitin describes how, beginning with the eardrum, sound waves are translated into pitch, or a tonotopic map, and then shortly thereafter "speech and music probably diverge into separate processing circuits" (130).[56] There is evidence that neural circuits used for music and language may start out in infants undifferentiated. There are several areas of the brain that are used for both language and music. For example, Brodmann area 47, which has been implicated in the processing of syntax in oral and sign languages, as well as musical syntax and semantic aspects of language. Levitin recounts how in certain studies, "listening to music and attending its syntactic features", similar to the syntactic processes in language, activated this part of the brain. In addition, "musical syntax ... has been localized to ... areas adjacent to and overlapping with those regions that process speech syntax, such as Broca's area" and "the regions involved in musical semantics ... appear to be [localized] near Wernicke's area." Both Broca's area and Wernicke's area are important steps in language processing and production.

Singing has been shown to help stroke victims recover speech. According to neurologist Gottfried Schlaug, there is a corresponding area to that of speech, which resides in the left hemisphere, on the right side of the brain.[57] This is casually known as the "singing center". By teaching stroke victims to sing their words, this can help train this area of the brain for speech. In support of this theory, Levitin asserts that "regional specificity", such as that for speech, "may be temporary, as the processing centers for important mental functions actually move to other regions after trauma or brain damage."[56] Thus in the right hemisphere of the brain, the "singing center" may be retrained to help produce speech.[58]

Accents and singing

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2013) |

The speaking dialect or accent of a person may differ greatly from the general singing accent that a person uses while singing. When people sing, they generally use the accent or neutral accent that is used in the style of music they are singing in, rather than a regional accent or dialect; the style of music and the popular center/region of the style has more influence on the singing accent of a person than where they come from. For example, in the English language, British singers of rock or popular music often sing in an American accent or neutral accent instead of an English accent.[59][60]

Legal

[edit]In Iran women are not allowed to sing.[61]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sears, Tom (2003). "Singing". In Blakemore, Colin; Jennett, Sheila (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Body. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191727511.

- ^ "Definition of SINGING". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Definition of sing | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: sing". ahdictionary.com. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "singing". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 16 December 2024.

- ^ "VOCALIST – meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". Dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Vocalist | Definition of vocalist in US English by Oxford Dictionaries". Archived from the original on 2 October 2018.

- ^ Falkner, Keith, ed. (1983). Voice. Yehudi Menuhin music guides. London: MacDonald Young. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-356-09099-3. OCLC 10418423.

- ^ a b Greenberg, Jonathan (31 January 2014). "Singing". Singing. Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2258282. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^ a b c Ashley, Martin (2015). Singing in the Lower Secondary School. Oxford University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-19-339900-6.

- ^ Condry, Ian (1999). Japanese Rap Music: An Ethnography of Globalization in Popular Culture. Yale University. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-349-33445-2.

- ^ Connor, Martin E. (2018). The Musical Artistry of Rap. McFarland & Company. p. 71. ISBN 9780786498987.

- ^ Berry, Michael (2018). "Chapter 3: Listening to the Voice". Listening to Rap: An Introduction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781315315867.

- ^ "Singing". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b c polka dots Vennard, William (1967). Singing: the mechanism and the technic. New York: Carl Fischer Music. ISBN 978-0-8258-0055-9. OCLC 248006248.

- ^ Hunter, Eric J; Titze, Ingo R (2004). "Overlap of hearing and voicing ranges in singing" (PDF). Journal of Singing. 61 (4): 387–392. PMC 2763406. PMID 19844607. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Hunter, Eric J; Švec, Jan G; Titze, Ingo R (December 2006). "Comparison of the produced and perceived voice range profiles in untrained and trained classical singers". J Voice. 20 (4): 513–526. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2005.08.009. PMC 4782147. PMID 16325373.

- ^ Titze, I. R. (23 September 1995). "What's in a voice". New Scientist: 38–42.

- ^ Speak and Choke 1, by Karl S. Kruszelnicki, ABC Science, News in Science, 2002

- ^ Lucero, Jorge C. (1995). "The minimum lung pressure to sustain vocal fold oscillation". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 98 (2): 779–784. Bibcode:1995ASAJ...98..779L. doi:10.1121/1.414354. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 7642816. S2CID 24053484.

- ^ Shewan, Robert (January–February 1979). "Voice classification: An examination of methodology". The NATS Bulletin. 35 (3): 17–27. ISSN 0884-8106. OCLC 16072337.

- ^ a b c Stark, James (2003). Bel Canto: A history of vocal pedagogy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8614-3. OCLC 53795639.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k McKinney, James C (1994). The diagnosis and correction of vocal faults. Nashville, TN: Genovex Music Group. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-56593-940-0. OCLC 30786430.

- ^ Smith, Brenda; Thayer Sataloff, Robert (2005). Choral pedagogy. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59756-043-6. OCLC 64198260.

- ^ Peckham, Anne (2005). Vocal workouts for the contemporary singer. Boston: Berklee Press. pp. 117. ISBN 978-0-87639-047-4. OCLC 60826564.

- ^ a b c Appelman, Dudley Ralph (1986). The science of vocal pedagogy: theory and application. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-253-35110-4. OCLC 13083085.

- ^ Lucero, Jorge C. (1996). "Chest- and falsetto-like oscillations in a two-mass model of the vocal folds". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 100 (5): 3355–3359. Bibcode:1996ASAJ..100.3355L. doi:10.1121/1.416976. ISSN 0001-4966.

- ^ Large, John W (February–March 1972). "Towards an integrated physiologic-acoustic theory of vocal registers". The NATS Bulletin. 28: 30–35. ISSN 0884-8106. OCLC 16072337.

- ^ Lucero, Jorge C.; Lourenço, Kélem G.; Hermant, Nicolas; Hirtum, Annemie Van; Pelorson, Xavier (2012). "Effect of source–tract acoustical coupling on the oscillation onset of the vocal folds" (PDF). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 132 (1): 403–411. Bibcode:2012ASAJ..132..403L. doi:10.1121/1.4728170. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 22779487. S2CID 29954321.

- ^ Margaret C. L. Greene; Mathieson, Lesley (2001). The voice and its disorders (6th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-86156-196-1. OCLC 47831173.

- ^ "What is Chest Voice, Head Voice, and Mix?" by KO NAKAMURA. SWVS journal. MARCH 11, 2017. [1]

- ^ Nickson, Chris (1998), Mariah Carey revisited: her story, St. Martin's Press, p. 32, ISBN 978-0-312-19512-0

- ^ Grove, George; Sadie, Stanley, eds. (1980). The New Grove Dictionary of Music & Musicians. Vol. 6: Edmund to Fryklunde. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-174-9. OCLC 191123244.

- ^ Clippinger, David Alva (1917). The head voice and other problems: Practical talks on singing. Oliver Ditson. p. 12.

- ^ Miller, Richard (2004). Solutions for singers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-19-516005-5. OCLC 51258100.

- ^ Warrack, John Hamilton; West, Ewan (1992). The Oxford dictionary of opera. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-869164-8. OCLC 25409395.

- ^ Ingo R. Titze, The Principles of Voice Production, Second Printing (Iowa City: National Center for Voice and Speech, 2000) 282.

- ^ Marilee David, The New Voice Pedagogy, 2nd ed. (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2008) 59.

- ^ Ingo R. Titze, The Principles of Voice Production, Second Printing (Iowa City: National Center for Voice and Speech, 2000) 281.

- ^ Miller, Richard (1986). The Structure of Singing. New York, NY: Schirmer Books. p. 115. ISBN 002872660X.

- ^ Richard Miller, The Structure of Singing: System and Art in Vocal Technique (New York: Schirmer Books: A Division of Macmillan, Inc., 1986) 115-149.

- ^ Marilee David, The New Voice Pedagogy, 2nd ed. (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2008) 63.

- ^ Richard Miller, The Structure of Singing: System and Art in Vocal Technique (New York: Schirmer Books: A Division of Macmillan, Inc., 1986) 125.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark (5 January 2013). "Ancient Greek Music". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Titze Ingo R (2008). "The human instrument". Scientific American. 298 (1): 94–101. Bibcode:2008SciAm.298a..94T. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0108-94. PMID 18225701.

- ^ Titze Ingo R (1994). Principles of voice production. Prentice Hall. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-13-717893-3. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ Ramsey, Matt (24 June 2020). "10 Singing Techniques to Improve Your Singing Voice". Ramsey Voice Studio.

- ^ "Is it good to take natural cough syrup to sing". VisiHow.

- ^ Sundberg, Johan (January–February 1993). "Breathing behavior during singing" (PDF). The NATS Journal. 49: 2–9, 49–51. ISSN 0884-8106. OCLC 16072337. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2019.

- ^ Fulford, Phyllis; Miller, Michael (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Singing. Penguin Books. p. 64.

- ^ Stark, James (2003). Bel Canto: A History of Vocal Pedagogy. University of Toronto Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8020-8614-3.

- ^ "National Association for Music Education (NAfME)". Menc.org. 29 June 2017. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "Contestants on Saregamapa". 10 March 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ a b Maler, Anabel (March 2013). "Songs for Hands: Analyzing Interactions of Sign Language and Music". Music Theory Online. 19 (1): 1–8. doi:10.30535/mto.19.1.4 – via Academic Search Premier.

- ^ "Justina Miles (Deaf performer) performs Super Bowl LVII 2023 Halftime show by Rihanna in ASL (HD)". YouTube. 18 February 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2024.

- ^ a b Levitin, Daniel J. (2006). This is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession. New York: Plume. ISBN 978-0-452-28852-2.

- ^ "Singing 'rewires' damaged brain". BBC News. 21 February 2010. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Loui, Psyche; Wan, Catherine Y.; Schlaug, Gottfried (July 2010). "Neurological Bases of Musical Disorders and Their Implications for Stroke Recovery" (PDF). Acoustics Today. 6 (3): 28–36. doi:10.1121/1.3488666. PMC 3145418. PMID 21804770.

- ^ Alleyne, Richard (2 August 2010). "Rock 'n' roll best sung in American accents". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 6 August 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Anderson, L.V. (19 November 2012). "Why Do British Singers Sound American?". Slate. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "Iran's judiciary opens case against female singer after viral 'imaginary' concert". ABC News.

Further reading

[edit]- Blackwood, Alan. The Performing World of the Singer. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1981. 113 p., amply ill. (mostly with photos.). ISBN 0-241-10588-9

- Platte, S. L.; et al. (2024). "Breathing with the Conductor? A Prospective, Quasi-Experimental Exploration of Breathing Habits in Choral Singers". Journal of Voice. 38 (1): 152–160. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2021.07.020. PMID 34551860. S2CID 237608913.

- Reid, Cornelius. A Dictionary of Vocal Terminology: an Analysis. New York: J. Patelson Music House, 1983. ISBN 0-915282-07-0

.jpg/250px-Ah_cricket_20122_(7364759010).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Ah_cricket_20122_(7364759010).jpg)