Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Music Row

View on Wikipedia

Music Row is a historic district located southwest of downtown Nashville, Tennessee, United States. Widely considered the heart of Nashville's entertainment industry, Music Row has also become a metonymous nickname for the music industry as a whole, particularly in country music, gospel music, and contemporary Christian music.

Key Information

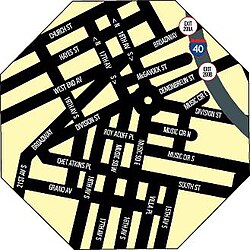

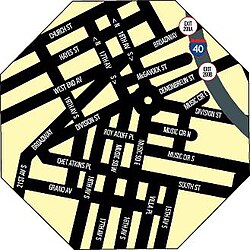

The district is centered on 16th and 17th Avenues South (called Music Square East and Music Square West, respectively, within the Music Row area), along with several side streets.[1] Lacy J. Dalton had a hit song in the 1980s about 16th Avenue, while the area served as namesake to Dolly Parton's 1973 composition "Down on Music Row". In 1999, the song "Murder on Music Row" was released and gained fame when it was recorded by George Strait and Alan Jackson, lamenting the rise of country pop and the accompanying decline of the traditional country music sound.[2][3]

The area hosts the offices of numerous record labels, publishing houses, music licensing firms, recording studios, video production houses, along with other businesses that serve the music industry, as well as radio networks, and radio stations. MusicRow Magazine has reported on the music industry since 1981.[4]

In present years, the district has been marked for extensive historical preservation and local as well as national movements to revive its rich and vibrant history. A group dedicated to this mission is the Music Industry Coalition.[5][6][7]

History

[edit]In his 1970 book The Nashville Sound, Paul Hemphill described Music Row as the area "where almost all of Nashville's music-related businesses operate out of a smorgasbord of renovated old single- and two-story houses and sleek new office buildings."[8] RCA Victor, Decca Records, and Columbia Records each completed at least 90 percent of country recordings at music Row.[9] Elsewhere, observed Hemphill, Music Row had "a montage of 'For Sale' signs [and] old houses done up with false fronts to look like office buildings."[9]

Throughout the 1960s, property values on Music Row grew, for instance a 50-foot lot from $15,000 in 1961 to $80,000 in 1966.[10]

Points of interest

[edit]Music Row includes historic sites such as RCA's famed Studio B and Studio A, where hundreds of notable and famous musicians have recorded. Country music entertainers Roy Acuff and Chet Atkins have streets named in their honor within the area.[11][12]

The Country Music Association (CMA) opened its $750,000 headquarters in Music Row in 1967. The modernist building included CMA's executive offices and the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.[9] Next door to the CMA headquarters is Broadcast Music Inc.[9]

The first Country Music Hall of Fame sat at the corner of Music Square East and Division Street from April 1967 to December 2000, but the building has since been torn down and the museum moved to a state-of-the-art building 11 blocks away in Downtown Nashville in May 2001.[13]

One area of Music Row, along Demonbreun Street, was once littered with down-market tourist attractions and vanity "museums" of various country music stars. These began to disappear in the late 1990s with the announced move of the Country Music Hall of Fame. The strip sat largely vacant for a few years but has been recently redeveloped with a number of upscale restaurants and bars serving the Downtown and Music Row areas.

At the confluence of Demonbreun Street, Division Street, 16th Avenue South, and Music Square East is the "Music Row Roundabout," a circular intersection designed to accommodate a continuous flow of traffic. Flanking the intersection to the west is Owen Bradley Park, a very small park dedicated to notable songwriter, performer, and publisher Owen Bradley. Within the park is a life-size bronze statue of Bradley behind a piano. Inside the roundabout is a large statue called the "Musica".[14]

At the other end of Music Row, across Wedgewood Avenue sits the Belmont University campus, and Vanderbilt University is also adjacent to the area. Belmont is of particular note because of its Mike Curb College of Entertainment & Music Business (CEMB), part of Belmont University and a major program in its commercial music performance division.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Sources

- Hemphill, Paul (1970). The Nashville Sound: Bright Lights and Country Music. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-20493-9.

- Notes

- ^ "Music Row, Nashville". Tennessee Encyclopedia. March 1, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ “Murder On Music Row” and McCourys Rake In Bluegrass Hardware

- ^ Alan Jackson gives Nashville the finger

- ^ "David Ross, Founder of Music Row". This Week In Music. Ian Rogers. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ Rau, Nate (November 21, 2016). "Music Row preservation takes major step forward". The Tennessean. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ "Nashville's Music Row". National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (May 2, 2016). "To Honor Nashville's Music Row, Entire District Submitted for Historic Recognition". Curbed.com. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Hemphill 1970, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b c d Hemphill 1970, p. 36.

- ^ Hemphill 1970, p. 37.

- ^ "RCA Studio B". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Garrison, Joey (October 21, 2017). "Iconic signs at Nashville's historic Studio A return after nearly 50 years". The Tennessean. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Thanki, Juli (March 24, 2017). "Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum celebrates 50 years". The Tennessean. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Todd, Jen (February 25, 2016). "Music Row statue Musica to get fountains". The Tennessean. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Michael Kosser (2006). How Nashville Became Music City, U.S.A.: 50 Years of Music Row. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-634-09806-2.