Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

1910s

View on Wikipedia

| Millennia |

|---|

| 2nd millennium |

| Centuries |

| Decades |

| Years |

| Categories |

The 1910s (pronounced "nineteen-tens" often shortened to the "'10s" or the "Tens") was the decade that began on January 1, 1910, and ended on December 31, 1919.

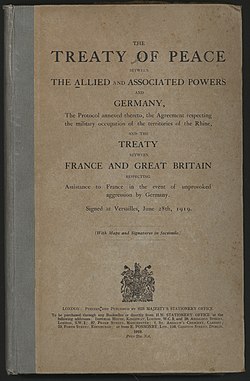

The 1910s represented the climax of European militarism which had its beginnings during the second half of the 19th century. The conservative lifestyles during the first half of the decade, as well as the legacy of military alliances, were forever changed by the June 28, 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne. The archduke's murder triggered a chain of events in which, within 33 days, World War I broke out in Europe on August 1, 1914. The conflict dragged on until a truce was declared on November 11, 1918, leading to the controversial and one-sided Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919.

The war's end triggered the abdication of various monarchies and the collapse of four of the last modern empires of Russia, Germany, Ottoman Turkey, and Austria-Hungary, with the latter splintered into Austria, Hungary, southern Poland (who acquired most of their land in a war with Soviet Russia), Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, as well as the unification of Romania with Transylvania and Bessarabia.[a] However, each of these states (with the possible exception of Yugoslavia) had large German and Hungarian minorities, creating some unexpected problems that would be brought to light in the next two decades.

The decade was also a period of revolution in many countries. The Portuguese 5 October 1910 revolution, which ended the eight-century-long monarchy, spearheaded the trend, followed by the Mexican Revolution in November 1910, which led to the ousting of dictator Porfirio Díaz, developing into a violent civil war that dragged on until mid-1920, not long after a new Mexican Constitution was signed and ratified. The Russian Empire had a similar fate, since its participation in World War I led it to a social, political, and economical collapse which made the tsarist autocracy unsustainable and, succeeding the events of 1905, culminated in the Russian Revolution and the establishment of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, under the direction of the Bolshevik Party, later renamed as the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The Russian Revolution of 1918, known as the October Revolution, was followed by the Russian Civil War, which dragged on until approximately late 1922. China saw 2,000 years of imperial rule ended with the Xinhai Revolution, becoming a nominal republic until Yuan Shikai's failed attempt to restore the monarchy and his death started the Warlord Era in 1916.

Much of the music in these years was ballroom-themed. Many of the fashionable restaurants were equipped with dance floors. Prohibition in the United States began January 16, 1919, with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Best-selling books of this decade include The Inside of the Cup, Seventeen, Mr. Britling Sees It Through, and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

During the 1910s, the world population increased from 1.75 to 1.87 billion, with approximately 640 million births and 500 million deaths in total.

Politics and wars

[edit]

Wars

[edit]- World War I (1914–1918)

- The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary in Sarajevo leads to the outbreak of the First World War.

- The Armenian genocide during and just after World War I. It was characterized by the use of massacres and deportations involving forced marches under conditions designed to lead to the death of the deportees, with the total number of Armenian deaths generally held to have been between one and one-and-a-half million.[1][2][3]

- The Arab Revolt was an armed uprising of Arabs against the Ottoman Empire.

- Germany signs the Treaty of Versailles after losing the First World War.

- Wadai War (1909–1911)

- Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912)

- Balkan Wars (1912–1913) – two wars that took place in South-eastern Europe in 1912 and 1913.

- Saudi-Ottoman War (1913)

- Latvian War of Independence (1918–1920) – a military conflict in Latvia between the Republic of Latvia and the Russian SFSR.

Internal conflicts

[edit]- The October Revolution in Russia results in the overthrow of capitalism and the establishment of the world's first self-proclaimed socialist state; political upheaval in Russia culminating in the establishment of the Russian SFSR and the assassination of Emperor Nicholas II and the royal family.

- The Russian Revolution is the collective term for the series of revolutions in Russia in 1917, which destroyed the Tsarist autocracy and led to the creation of the Soviet Union. It led to the Russian Civil War and other conflicts such as the Finnish Civil War, the Ukrainian War of Independence and the Polish–Soviet War.

- The Jallianwala Bagh massacre (1919), at Amritsar in the Punjab Province of British India, sows the seeds of discontent and leads to the birth of the Indian independence movement.

- The Xinhai Revolution causes the overthrow of China's ruling Qing dynasty, and the establishment of the Republic of China. The Warlord Era (1916–1928) began.

- The Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) Francsico Madero proclaims the elections of 1910 null and void and calls for an armed revolution at 6 p.m. against the illegitimate presidency/dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. The revolution led to the ousting of Díaz (who ruled from 1876 to 1880 and since 1884) six months later. The revolution progressively became a civil war with multiple factions and phases, culminating with the Mexican Constitution of 1917, but combat would persist for three more years.

- The German Revolution of 1918-1919 is fought between the workers and soldiers at the tail end of World War I, leading to the creation of the Weimar-era Freikorps, paramilitary units that would be a decisive political force throughout the Weimar Era.[4]

Major political change

[edit]

- Portugal became the first republican country in the century after the 5 October 1910 revolution, ending its long-standing monarchy and creating the First Portuguese Republic in 1911.

- Germany abolished its monarchy and established a new elected government, the Weimar Republic.

- Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution is passed, requiring US senators to be directly elected rather than appointed by the state legislatures.

- Federal Reserve Act is passed in 1913 by the United States Congress, establishing a Central Bank in the US.

- On the death of Edward VII, his son George V becomes King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India. The Coronation of George V and Mary takes place on 22 June 1911.

- Dissolution of the German colonial empire, Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary and the Russian Empire, reorganization of European states, territorial boundaries, and the creation of several new European states and territorial entities: Austria, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Finland, Free City of Danzig, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Saar, Ukraine, and Yugoslavia.

- Fourteen Points as designed by United States President Woodrow Wilson advocates the right of all nations to self-determination.

- Rise to power of the Bolsheviks in Russia under Vladimir Lenin, creating the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic, the first state committed to the establishment of communism.

- The Balfour Declaration was a declaration by the British Government that announced the British desire to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. This declaration has often been characterized as a betrayal of the Arabs and the agreement between the British and Sharif Hussein of Mecca in the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence which promised freedom to all Arab lands from the Ottoman Empire.[5][6][7]

- Zionism becomes more popular after the Balfour Declaration.[where?]

Decolonization and independence

[edit]- The Easter Rising against the British in Ireland eventually leads to Irish independence.

- Several nations in Eastern Europe get their nation-state, thereby replacing major multiethnic empires.

- The Republic of China was established on January 1, 1912.

Assassinations

[edit]Prominent assassinations include:

- March 18, 1913: George I of Greece

- June 11, 1913: Mahmud Şevket Pasha, Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire

- June 28, 1914: Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary is assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina; prompting the events that led up to the start of World War I.

- July 17, 1918: Murder of the Romanov family, including former Russian Emperor Nicholas II, his consort Alix of Hesse, their five children, and four retainers at the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg following the October Revolution of 1917, and the usurpation of power by the Bolsheviks.

- April 10, 1919: Emiliano Zapata in Mexico.

Disasters

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

- The RMS Titanic, a British ocean liner which was the largest and most luxurious ship at that time, struck an iceberg and sank two hours and 40 minutes later in the North Atlantic during its maiden voyage on April 15, 1912. 1,517 people perished in the disaster.

- On May 29, 1914, the British ocean liner RMS Empress of Ireland collided in thick fog with the SS Storstad, a Norwegian collier, near the mouth of Saint Lawrence River in Canada, sinking in 14 minutes. 1,012 people died.

- On May 7, 1915, the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed by U-20, a German U-boat, off the Old Head of Kinsale in Ireland, sinking in 18 minutes. 1,199 people died.

- On November 21, 1916, HMHS Britannic was holed in an explosion while passing through a channel that had been seeded with enemy mines and sank in 55 minutes.

- From 1918 through 1920, the Spanish flu killed from 17.4 to 100 million people worldwide.

- In 1916, the Netherlands was hit by a North Sea storm that flooded the lowlands and killed 19 people.

- From July 1 to July 12, 1916, a series of shark attacks, known as the Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916, occurred along the Jersey Shore, killing four and injuring one.

- On January 11, 1914, Sakurajima erupted which resulted in the death of 35 people. In addition, the surrounding islands were consumed, and an isthmus was created between Sakurajima and the mainland.

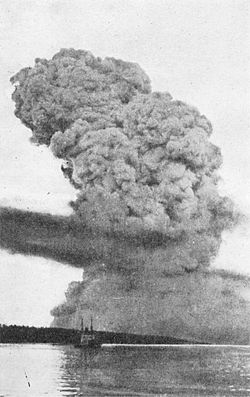

- In 1917, the Halifax Explosion killed 2,000 people.

- In 1919, the Great Molasses Flood in Boston, Massachusetts killed 21 people and injured 150.

Other significant international events

[edit]- The Panama Canal is completed in 1914.

- World War I from 1914 until 1918 dominates the Western world.

- Hiram Bingham rediscovers Machu Picchu on July 24, 1911.

Science and technology

[edit]Technology

[edit]

- In 1912, articulated trams, were invented and first used by the Boston Elevated Railway.[8]

- In 1913, the Haber process was first utilized on an industrial scale.[9]

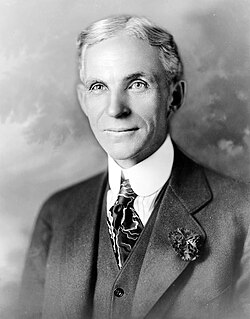

- The Model T Ford dominated the automobile market, selling more than all other makers combined in 1914.[10]

- In 1916, Jan Czochralski invented the Czochralski process.[11]

- In 1917, Alexander M. Nicolson invented the crystal oscillator using a piece of Rochelle salt.[12]

- In 1919, Alice Parker invented the first system of natural gas-powered central heating for homes

- Gideon Sundback patented the first modern zipper.[13]

- Harry Brearley invented stainless steel.[14]

- Charles Strite invented the first pop-up bread toaster.[15]

- The army tank was invented. Tanks in World War I were used by the British Army, the French Army and the German Army.[16]

Science

[edit]- In 1911, the cloud chamber was invented by Charles Thomson Rees Wilson.[17]

- Victor Hess’s daring balloon experiments in 1912 led to the discovery of cosmic rays.[18]

- In 1912, Alfred Wegener puts forward his theory of continental drift.[19]

- In 1913, Niels Bohr introduced the Bohr model his revolutionary model of the atom.[20]

- In 1916, Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity.[21]

- Noether's first theorem was proven by mathematician Emmy Noether in 1915 and was published in 1918

- Max von Laue discovers the diffraction of x-rays by crystals.[22]

Economics

[edit]- In the years 1910 and 1911, there was a minor economic depression known as the Panic of 1910–1911, which was followed by the enforcement of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.

- The outbreak of World War I caused the Financial Crisis of 1914, leading to the closure of the New York Stock Exchange for four months. U.S. Treasury Secretary William McAdoo implemented measures to stabilize the economy, marking the United States' transition from a debtor to a creditor nation.[23]

- Following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, Russia experienced severe hyperinflation due to economic disarray and war. By 1924, three currency redenominations occurred, culminating in the introduction of the "gold ruble," stabilizing the economy.[24]

- The United States emerged as a global economic power during World War I, benefiting from industrial expansion and increased consumerism. Wartime loans to Allied nations further strengthened its financial position.[25]

- The British government implemented extensive controls during World War I under the Defense of the Realm Act, nationalizing key industries and introducing food rationing. Postwar economic challenges included high debt and unemployment.[26]

- Germany's wartime mobilization strained its economy, leading to shortages and inflation. The Treaty of Versailles in 1919 imposed reparations that further destabilized its postwar economy.[27]

- Italy faced significant economic challenges during World War I, including a 40% devaluation of its currency relative to the British pound. Allied intervention stabilized its currency in 1918.[28]

- Japan experienced rapid industrialization during World War I, driven by increased demand for exports such as textiles and machinery. This period saw significant growth in heavy industries like steel and shipbuilding, concentrated in urban centers along the Tōkaidō industrial belt.[29]

Popular culture

[edit]- Flying Squadron of America promotes temperance movement in the United States.

- Edith Smith Davis edits the Temperance Educational Quarterly.

- The first U.S. feature film, Oliver Twist, was released in 1912.

- The first mob film, D. W. Griffith's The Musketeers of Pig Alley, was released in 1912.

- Hollywood, California, replaces the East Coast as the center of the movie industry.

- The first crossword puzzle was published 21 December 1913 appearing in The New York World newspaper.

- The comic strip Krazy Kat begins.

- Charlie Chaplin débuts his trademark mustached, baggy-pants "Little Tramp" character in Kid Auto Races at Venice in 1914.

- The first African American owned studio, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, was founded in 1917.

- The four Warner brothers, (from older to younger) Harry, Albert, Samuel, and Jack opened their first major film studio in Burbank in 1918.

- Tarzan of the Apes starring Elmo Lincoln is released in 1918, the first Tarzan film.

- The first jazz music is recorded by the Original Dixieland Jass Band for Victor (#18255) in late February 1917.

- The Salvation Army has a new international leader, General Bramwell Booth who served from 1912 to 1929. He replaces his father and co-founder of the Christian Mission (the forerunner of the Salvation Army), William Booth.

Sports

[edit]- 1912 Summer Olympics were held in Stockholm, Sweden.

- 1916 Summer Olympics were cancelled because of World War I.

Literature and arts

[edit]Below are the best-selling books in the United States of each year, as determined by The Bookman, a New York-based literary journal (1910–1912) and Publishers Weekly (1913 and beyond).[30]

- 1910: The Rosary by Florence L. Barclay

- 1911: The Broad Highway by Jeffery Farnol

- 1912: The Harvester by Gene Stratton Porter

- 1913: The Inside of the Cup by Winston Churchill

- 1914: The Eyes of the World by Harold Bell Wright

- 1915: The Turmoil by Booth Tarkington

- 1916: Seventeen by Booth Tarkington

- 1917: Mr. Britling Sees It Through by H. G. Wells

- 1918: The U.P. Trail by Zane Grey

- 1919: The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez

Visual Arts

[edit]-

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, The Art Institute of Chicago. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque co-invent Cubism, revolutionizing the art of painting and advancing the concepts of Modern art and Modernism.

-

Henri Matisse, L'Atelier Rouge, 1911, oil on canvas, 162 × 130 cm., The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

-

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917, Duchamp introduces his Readymades, as an example of Dada and Anti-art. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz

-

Armory Show poster, 1913, Internationally groundbreaking exhibition of Modern art

The 1913 Armory Show in New York City was a seminal event in the history of Modern Art. Innovative contemporaneous artists from Europe and the United States exhibited together in a massive group exhibition in New York City, and Chicago.

Art movements

[edit]Expressionism and related movements

[edit]Geometric abstraction and related movements

[edit]Other movements and techniques

[edit]Influential artists

[edit]People

[edit]Business

[edit]

- Arnold Rothstein, gangster, gambler, fixed the 1919 World Series

- Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

Inventors

[edit]Politics

[edit]- John Barrett, Director-general Organization of American States

- George Louis Beer, Chairman Permanent Mandates Commission

- Henry P. Davison, Chairman International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- Sir James Eric Drummond, Secretary-general League of Nations

- Emil Frey, Director International Telecommunication Union

- Christian Louis Lange, Secretary-general Inter-Parliamentary Union

- Baron Louis Paul Marie Hubert Michiels van Verduynen, Secretary-general Permanent Court of Arbitration

- William E. Rappard, Secretary-general International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- Manfred von Richthofen, alias the "Red Baron", fighter pilot

- Eugène Ruffy, Director Universal Postal Union

- William Napier Shaw, President World Meteorological Organization

- Albert Thomas, Director International Labour Organization

- Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Communist International

Authors

[edit]Entertainers

[edit]

- Fatty Arbuckle

- Theda Bara

- Richard Barthelmess

- Béla Bartók

- Irving Berlin

- Eubie Blake

- Shelton Brooks

- Lew Brown

- Tom Brown

- Anne Caldwell

- Eddie Cantor

- Enrico Caruso

- Charlie Chaplin

- Lon Chaney

- George M. Cohan

- Henry Creamer

- Bebe Daniels

- Cecil B. DeMille

- Buddy De Sylva

- Walter Donaldson

- Marie Dressler

- Eddie Edwards

- Gus Edwards

- Douglas Fairbanks

- Fred Fisher

- John Ford

- Eddie Foy

- George Gershwin

- Beniamino Gigli

- Dorothy Gish

- Lillian Gish

- Samuel Goldwyn

- D. W. Griffith

- W. C. Handy

- Otto Harbach

- Lorenz Hart

- Victor Herbert

- Harry Houdini

- Charles Ives

- Tony Jackson

- Emil Jannings

- William Jerome

- Al Jolson

- Gus Kahn

- Gustave Kahn

- Buster Keaton

- Jerome David Kern

- Ring Lardner

- Nick LaRocca

- Harry Lauder

- Florence Lawrence

- Ted Lewis

- Harold Lloyd

- Charles McCarron

- Joseph McCarthy

- Winsor McCay

- Oscar Micheaux

- Mae Murray

- Alla Nazimova

- Pola Negri

- Anna Q. Nilsson

- Mabel Normand

- Ivor Novello

- Alcide Nunez

- Geoffrey O'Hara

- Sidney Olcott

- Jack Pickford

- Mary Pickford

- Armand J. Piron

- Cole Porter

- American Quartet

- Richard Rodgers

- Sigmund Romberg

- Jean Schwartz

- Mack Sennett

- Larry Shields

- Chris Smith

- Erich von Stroheim

- Arthur Sullivan

- Gloria Swanson

- Wilber Sweatman

- Blanche Sweet

- Albert Von Tilzer

- Harry Von Tilzer

- Musicians of the Titanic

- Sophie Tucker

- Pete Wendling

- Pearl White

- Bert Williams

- Clarence Williams

- Harry Williams

- Spencer Williams

- P. G. Wodehouse

Sports figures

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (November 2023) |

Baseball

[edit]

- Babe Ruth, (American baseball player)

- Honus Wagner, (American baseball player)

- Christy Mathewson, (American baseball player)

- Walter Johnson, (American baseball player)

- Ty Cobb, (American baseball player)

- Tris Speaker, (American baseball player)

- Nap Lajoie, (American baseball player)

- Eddie Collins, (American baseball player)

- Mordecai Brown, (American baseball player)

Olympics

[edit]Boxing

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of decades, centuries, and millennia

- Edwardian era (commonly extended into the decade's early years)

- Progressive Era (up until late into the decade)

- List of years in literature § 1910s

- Lost Generation (the decade when the majority of the WWI vets came of age)

- Interbellum Generation (when the oldest members of that demographic had matured in the decade's final year)

Timeline

[edit]The following articles contain brief timelines which list the most prominent events of the decade:

1910 • 1911 • 1912 • 1913 • 1914 • 1915 • 1916 • 1917 • 1918 • 1919

Notes

[edit]- ^ See Dissolution of Austria-Hungary § Successor states for better description of composition of names of successor countries following the splinter.

References

[edit]- ^ Dictionary of Genocide, by Samuel Totten, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, ISBN 0-313-34642-9, p. 19

- ^ Intolerance: a general survey, by Lise Noël, Arnold Bennett, 1994, ISBN 0773511873, p. 101

- ^ Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, by Richard T. Schaefer, 2008, p. 90

- ^ Pool, James & Suzanne. Who Financed Hitler?. pp. 230–233.

- ^ "The Mcmahon Correspondence of 1915–16." Bulletin of International News, vol. 16, no. 5, 1939, pp. 6–13. JSTOR, JSTOR 25642429. Accessed 8 Nov. 2023.

- ^ Sole, Kent M. "THE ARABS, A PEOPLE BETRAYED." Journal of Third World Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, 1985, pp. 59–62. JSTOR, JSTOR 45197139. Accessed 8 Nov. 2023.

- ^ Barnett, David (2022-10-30). "Revealed: TE Lawrence felt 'bitter shame' over UK's false promises of Arab self-rule". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ MBTA (2010). "About the MBTA-The "El"". MBTA. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ Philip, Phylis Morrison (2001). "Fertile Minds (Book Review of Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production)". American Scientist. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (2004). Wheels for the world : Henry Ford, his company, and a Century of progress, 1903–2003. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780142004395. OCLC 796971541.

- ^ "Czochralski Process and Silicon Wafers". www.waferworld.com. Retrieved 2025-03-13.

- ^ Nicolson, Alexander M. Generating and transmitting electric currents U.S. patent 2,212,845, filed April 10, 1918, granted August 27, 1940

- ^ Friedel, Robert D (1996). Zipper : an Exploration in Novelty. New York: Norton. p. 94. ISBN 0393313654. OCLC 757885297.

- ^ "A Non-Rusting Steel: Sheffield Invention Especially Good for Table Cutlery" (PDF). The New York Times. 1914-01-31. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ^ "Bread-toaster" (Patent #1,387,670 application filed May 29, 1919, granted August 16, 1921). Google Patents. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Watson, Greig (2014-02-24). "World War One: The tank's secret Lincoln origins". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ^ "Nobel Prize in Physics 1927". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2025-03-13.

- ^ "Victor Hess discovers cosmic rays | timeline.web.cern.ch". timeline.web.cern.ch. Retrieved 2025-03-13.

- ^ Demhardt, Imre (2012) [1912]. "Alfred Wegeners Hypothesis on Continental Drift and its Discussion in Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen" (PDF). Polarforschung. 75: 29–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-04.

- ^ "Bohr Atomic Theory". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 March 2025.

- ^ O'Conner, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (May 1996). "General relativity". st-andrews.ac.uk. University of St. Andrews. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ^ "Gerade auf LeMO gesehen: LeMO Bestand: Biografie". dhm.de (in German). Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum. 2014-09-14. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ^ Silber, William L. (2007). When Washington Shut Down Wall Street: The Great Financial Crisis of 1914 and the Origins of America's Monetary Supremacy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13876-3.

- ^ Efremov, Steven (2012-08-15). "The Role of Inflation in Soviet History: Prices, Living Standards, and Political Change". Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (2004). Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress, 1903–2003. Penguin Books.

- ^ Marwick, Arthur (1965). The Deluge: British Society and the First World War. Bodley Head.

- ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1919). The Economic Consequences of the Peace. Macmillan & Co.

- ^ Sarti, Roland (2004). "Italy: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present". Facts on File Library of World History.

- ^ "Japanese Industrialization and Economic Growth". eH.net. Retrieved 2025-03-14.

- ^ "Annual Bestsellers, 1910–1919". 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-10-16.

Further reading

[edit]- Blanke, David. The 1910s (Greenwood, 2002); popular culture in USA online.

- Craats, Rennay. 1910s (2012) for Canadian middle schools online

- Chisholm, Hugh (1913). Britannica Year-book 1913. pp. 1 v. (worldwide coverage for 1910–1912)

- Cornelissen, Christoph, and Arndt Weinrich, eds. Writing the Great War – The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present (2020) free download; advanced coverage of major countries.

- Sharman, Margaret. 1910s (1991) European history for middle schools. online

- Uschan, Michael V. The 1910s (1999) a cultural history of USA, for secondary schools. online

- Whalan, Mark. American Culture in the 1910s (Edinburgh University Press, 2010).

1910s

View on GrokipediaThe 1910s was a decade of seismic global transformations, from January 1, 1910, to December 31, 1919, overshadowed by the First World War (1914–1918), which mobilized over 70 million military personnel and inflicted more than 9 million military deaths alongside approximately 5 million civilian fatalities, fundamentally altering international power structures through the dissolution of empires including the German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman.[1] The war's trench stalemates, industrialized killing via machine guns and artillery, and involvement of colonial forces underscored the era's shift toward total warfare, culminating in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles that imposed punitive terms on the Central Powers, sowing seeds for future instability. Concurrently, the 1917 Russian Revolutions—first deposing Tsar Nicholas II in February amid wartime privations and then installing Bolshevik rule under Vladimir Lenin in October—heralded the advent of communist governance and civil war, fracturing the Russian Empire. The decade's cataclysmic toll extended beyond combat with the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic, claiming an estimated 50 million lives worldwide, exceeding war dead and exposing vulnerabilities in global health amid troop movements. Technological strides, such as Henry Ford's 1913 introduction of the moving assembly line for the Model T automobile, revolutionized mass production and mobility, while aviation and tank prototypes emerged from wartime necessities. Culturally, the period witnessed the rise of modernism in art through Cubism and Dada, alongside the maturation of cinema with feature-length films and stars like Charlie Chaplin, reflecting societal flux toward urbanization and women's expanding roles, evidenced by suffrage gains like New Zealand's precedents and U.S. momentum toward the 19th Amendment.[2]

Overview

Chronological Summary

![Montage of key events from the 1910s][float-right] The decade began with significant political upheavals, including the Mexican Revolution starting in 1910, which overthrew the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz after widespread discontent with economic inequality and foreign influence.[3] In China, the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 ended over two millennia of imperial rule, establishing the Republic of China under Sun Yat-sen following the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.[3] Italy's invasion of Libya in 1911 marked the Italo-Turkish War, resulting in Italy's annexation of Ottoman territories in North Africa.[3] The Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 saw the Balkan League defeat the Ottoman Empire, redrawing regional boundaries and heightening ethnic tensions that contributed to broader European instability.[4] Maritime disasters underscored technological vulnerabilities, with the RMS Titanic sinking on April 15, 1912, after striking an iceberg, claiming over 1,500 lives and prompting international safety regulations for ocean liners.[4] Exploration milestones included Roald Amundsen reaching the South Pole on December 14, 1911, ahead of Robert Falcon Scott's fatal British expedition.[5] Tensions in Europe escalated with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, by Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb nationalist, triggering Austria-Hungary's ultimatum to Serbia and the July Crisis.[6] World War I erupted on July 28, 1914, as Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, drawing in alliances: Germany invaded Belgium and France on August 4, prompting Britain to enter the conflict, while Russia mobilized against Austria-Hungary and Germany.[6] The war's early phase featured the Schlieffen Plan's failure, leading to trench stalemate on the Western Front by late 1914, with battles like the Marne (September 1914) and Ypres halting German advances. On the Eastern Front, Russia's invasion of East Prussia was repelled at Tannenberg (August 1914). Naval engagements included the Battle of Jutland (May 1916), the war's largest fleet clash, which maintained British dominance despite heavy losses.[4] The Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in October 1914, opening fronts in the Middle East and Caucasus, while Bulgaria aligned with them in 1915.[4] Italy entered on the Allied side in May 1915 after the Treaty of London promised territorial gains.[4] Unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany from 1917 alienated neutrals, sinking the Lusitania in 1915 (1,198 deaths) and resuming in 1917, which, combined with the Zimmermann Telegram proposing a Mexican alliance against the U.S., prompted American entry on April 6, 1917.[4] The Russian February Revolution of 1917 abdicated Tsar Nicholas II amid war fatigue and food shortages, establishing a provisional government, followed by the Bolshevik October Revolution led by Vladimir Lenin, seizing power and exiting the war via the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918). Civil war ensued in Russia as Bolsheviks consolidated control against White forces. The war's end came with the Armistice of November 11, 1918, after Allied offensives, including the Hundred Days Offensive, broke German lines, exacerbated by internal revolution and naval mutiny. Casualties exceeded 16 million military and civilian deaths, with the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic killing an estimated 50 million worldwide, facilitated by troop movements.[4] The Paris Peace Conference in 1919 produced the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, imposing reparations, territorial losses, and disarmament on Germany, while creating the League of Nations, though the U.S. Senate rejected ratification.[4] Other treaties redrew maps, dissolving empires and fostering new nations amid ongoing conflicts like the Greco-Turkish War.[4]Defining Global Themes

The 1910s were defined by the eruption of World War I in 1914, the first industrialized global conflict that mobilized over 65 million soldiers and resulted in approximately 9.7 million military deaths and 6.8 million civilian fatalities from warfare, famine, and disease.[7] Triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, and exacerbated by rigid alliance systems, imperial rivalries, and arms races among European powers, the war expanded beyond Europe to colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, introducing total war tactics including trench warfare, chemical weapons, and aerial bombing.[4] This catastrophe dismantled four major empires—the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian—reshaping national boundaries and sowing seeds for future instability through punitive treaties like Versailles in 1919.[5] Amid the war's devastation, revolutionary upheavals and a global pandemic amplified the era's turmoil. The Russian Revolutions of 1917, beginning with the February overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II and culminating in the Bolshevik October seizure of power under Vladimir Lenin, established the world's first communist state and inspired worldwide socialist movements, influencing labor unrest and anti-colonial agitation from Europe to Asia.[8] The 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, originating likely from military camps and spreading via troop movements, infected one-third of the global population and caused an estimated 50 million deaths, exceeding World War I's toll and straining post-war recovery efforts.[9] These events underscored vulnerabilities in centralized empires and mobilized societies, accelerating demands for self-determination and social reform. Parallel to geopolitical fractures, the 1910s witnessed cultural and scientific modernism challenging traditional paradigms. Artistic innovations like Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque around 1910, fragmented representation to reflect subjective perception, while Dada in 1917 rejected rationality amid war's absurdity./05:A_World_in_Turmoil(1900-1940)/5.05:American_Modernism(1910-1935)) Scientifically, Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1915, revolutionizing understandings of gravity and space-time, and the Haber-Bosch process enabled mass ammonia production for fertilizers and explosives, demonstrating technology's dual civilian and martial applications.[10] These advancements, occurring against a backdrop of destruction, highlighted the decade's paradoxical drive toward innovation, laying foundations for 20th-century progress despite immediate human costs.[11]International Relations and Conflicts

World War I: Causes and Outbreak

![Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, whose assassination triggered the July Crisis]float-right The causes of World War I encompassed intertwined long-term tensions in Europe, including militarism, alliance systems, imperial rivalries, and nationalism, which created a volatile international environment primed for conflict. Militarism fueled an arms race, particularly the Anglo-German naval competition, where Germany's construction of dreadnought battleships under the Tirpitz Plan challenged Britain's naval supremacy, leading to heightened suspicions and military planning for rapid mobilization.[12][13] The alliance system rigidified divisions: the Triple Alliance bound Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy, while the Triple Entente linked France, Russia, and Britain through mutual defense understandings, turning potential bilateral disputes into continental escalations.[14] Imperialism exacerbated frictions through colonial scrambles, as seen in the Moroccan Crises of 1905 and 1911, where German challenges to French influence in North Africa tested alliance commitments and nearly provoked war.[13] Nationalism, especially in the Balkans, intensified pressures; Serbian irredentism sought to unite South Slavs, undermining Austria-Hungary's multi-ethnic empire and prompting fears of disintegration.[15] The immediate trigger occurred on June 28, 1914, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie were assassinated in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb nationalist affiliated with the Black Hand group backed by elements in the Serbian military.[13] This act provided Austria-Hungary, seeking to assert dominance over Serbia and curb Slavic nationalism, an opportunity to deliver a harsh ultimatum on July 23, 1914, demanding suppression of anti-Austrian activities, participation in investigations, and arrest of conspirators—terms Serbia partially accepted on July 25 but which Vienna deemed insufficient.[16] Germany provided Austria-Hungary with a "blank cheque" of support around July 6, encouraging aggressive action without restraint, reflecting Berlin's strategic interest in backing its ally against Russian influence in the Balkans.[17] The July Crisis escalated rapidly due to mobilization timetables and perceived threats of preemption. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914, prompting Russia to order partial mobilization against Austria on July 29 and full general mobilization on July 30 to honor its Slavic ally and deter further aggression.[13] Germany, viewing Russian mobilization as a direct threat, demanded its halt on July 31; receiving no compliance, Berlin declared war on Russia on August 1, 1914, and implemented the Schlieffen Plan by declaring war on France on August 3 and invading neutral Belgium on August 4.[17] Britain, committed to Belgian neutrality via the 1839 Treaty of London and wary of German dominance, issued an ultimatum on August 4, leading to its declaration of war on Germany that evening, thus drawing in the Entente powers.[13] These decisions, driven by fear of disadvantage in delayed mobilization—where armies could deploy millions within days—escalated a regional Balkan conflict into a general European war, with structural rigidities preventing de-escalation despite diplomatic efforts like British mediation proposals.[16]World War I: Major Phases and Battles

World War I transitioned from rapid maneuvers in 1914 to entrenched stalemate by late that year, followed by attritional battles through 1917, and decisive offensives in 1918 leading to Allied victory.[18] The initial war of movement on the Western Front saw German forces execute the Schlieffen Plan, invading neutral Belgium on August 4, 1914, and advancing toward Paris, but halted by the Allied victory at the First Battle of the Marne from September 6–12, 1914, which prevented the fall of the French capital and initiated trench lines from the North Sea to Switzerland.[19] On the Eastern Front, the Battle of Tannenberg (August 26–30, 1914) resulted in a decisive Russian defeat, with over 120,000 Russian casualties and the encirclement of the Russian Second Army, due to superior German coordination under Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff.[20] The trench warfare phase dominated 1915–1917, characterized by static fronts, massive artillery barrages, and high casualties from failed infantry assaults. The Gallipoli Campaign (April 25, 1915–January 9, 1916) aimed to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war but ended in Allied evacuation after 250,000 casualties, highlighting logistical failures and Ottoman defenses under Mustafa Kemal.[21] In 1916, the Battle of Verdun (February 21–December 18, 1916) became a prolonged meat grinder, with French forces under Philippe Pétain holding against German attacks, incurring 700,000–1,250,000 total casualties as both sides sought to "bleed the enemy white."[20] The Battle of the Somme (July 1–November 18, 1916), intended to relieve Verdun, saw British forces suffer 57,000 casualties on the first day alone, totaling over 1 million combined losses, with minimal territorial gains but introduction of tanks on September 15. By 1917, mutinies in the French army after the failed Nivelle Offensive (April 16–May 9, 1917) and the disastrous Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) (July 31–November 10, 1917), which yielded five miles of mud-choked ground at 500,000 casualties, exemplified the stalemate's toll.[19] The Central Powers' Caporetto Offensive (October 24–November 19, 1917) shattered Italian lines, capturing 300,000 prisoners and forcing retreat, but strained German resources.[21] The United States' entry on April 6, 1917, following unrestricted submarine warfare, began shifting the balance, though American Expeditionary Forces saw first combat at Cantigny on May 28, 1918.[18] In 1918, Germany's Spring Offensives, including Operation Michael (March 21–April 5, 1918), achieved initial breakthroughs using stormtrooper tactics and gained 40 miles but faltered due to supply shortages and exhaustion, with 239,000 German casualties.[22] Allied responses, bolstered by fresh American troops, culminated in the Hundred Days Offensive, starting with the Battle of Amiens (August 8, 1918), where tanks and air power enabled rapid advances, inflicting 75,000 German losses in days and marking the "Black Day of the German Army."[19] The Meuse-Argonne Offensive (September 26–November 11, 1918) involved 1.2 million U.S. troops, resulting in 26,000 American deaths and breaking German lines, contributing to the armistice on November 11, 1918.[23] These phases underscored how technological stalemates gave way to combined arms maneuvers under superior Allied resources and manpower.[24]World War I: Home Fronts and Societal Impacts

Governments across belligerent nations implemented total war economies, directing industrial production toward munitions and supplies while imposing state controls on labor, resources, and transportation. In Britain, the Defence of the Realm Act of 1914 enabled the government to requisition factories and raw materials, leading to a tripling of munitions output by 1918.[25] Similar measures in the United States, through the War Industries Board established in 1917, coordinated production and prioritized military needs, averting shortages in key sectors like steel and chemicals.[26] These efforts strained civilian economies, fostering inflation and debt; for instance, British national debt rose from £650 million in 1914 to over £7 billion by 1919 due to war financing via bonds and taxes.[27] Labor shortages from male conscription drew women into factories, agriculture, and clerical roles, temporarily expanding female employment. In the United Kingdom, women's workforce participation climbed from 23.6 percent of the working-age population in 1914 to 37.7–46.7 percent by 1918, with over 900,000 filling roles in munitions and transport.[28] Germany employed nearly 1.4 million women in war-related industries by 1917, comprising 30 percent of its armaments workforce.[29] In the United States, women constituted about 20 percent of manufacturing workers by war's end, often in hazardous munitions assembly where accidents caused thousands of injuries from toxic exposure like TNT poisoning, dubbed "canary girls" for yellowed skin.[30] These shifts challenged traditional gender norms but proved largely reversible post-armistice, as returning veterans displaced many women amid economic contraction.[31] Food rationing became widespread to combat shortages exacerbated by naval blockades and U-boat campaigns, prioritizing military needs over civilian consumption. Britain introduced voluntary conservation in 1915 before compulsory rationing of meat, sugar, and butter in 1918, reducing per capita consumption by 20–30 percent in staples like wheat.[25] Germany's "Turnip Winter" of 1916–1917, triggered by a potato crop failure and Allied blockade, led to widespread malnutrition, with daily caloric intake dropping below 1,000 for many urban dwellers and contributing to over 400,000 excess civilian deaths from starvation-related causes.[32] The United States avoided formal rationing but promoted "wheatless" and "meatless" days via the Food Administration under Herbert Hoover, conserving 15 percent of grain for export to allies.[33] Such policies sparked social unrest, including riots in Berlin over bread queues and strikes in Allied nations demanding equitable distribution.[34] Propaganda campaigns sustained morale and recruitment, while conscription provoked resistance amid growing war fatigue. British and American governments distributed millions of posters depicting German atrocities to justify enlistment, with the U.S. Committee on Public Information producing films and pamphlets reaching 75 million citizens.[35] Conscription laws, such as Britain's Military Service Act of 1916, drafted over 2.5 million men but faced opposition, including a Trafalgar Square protest of 200,000 in April 1916 and exemptions for conscientious objectors numbering around 16,000, many imprisoned.[36] In the U.S., the Selective Service Act of 1917 registered 24 million men, enforced by Espionage and Sedition Acts that prosecuted over 2,000 for dissent, curbing anti-war speech.[37] These measures reflected causal pressures of prolonged stalemate, where voluntary recruitment faltered after initial enthusiasm, but also sowed domestic divisions exploited by labor strikes, totaling 4,000 in the U.S. alone in 1917–1918.[38] Societal impacts extended to civilian hardships and demographic shifts, with air raids and disease amplifying war's toll. German zeppelin and Gotha bomber attacks on Britain from 1915 killed 1,414 and injured 3,416 by 1918, prompting blackouts and shelter drills that disrupted daily life.[39] The 1918 influenza pandemic, facilitated by troop movements, killed an estimated 50 million worldwide, including 675,000 Americans, overwhelming home front medical systems already strained by resource diversion.[40] Racial and class tensions surfaced, as in the U.S. Great Migration of 500,000 African Americans to northern factories, fueling urban riots like Chicago's in 1919 with 38 deaths.[37] Overall, civilian deaths reached about 7 million from direct and indirect causes, underscoring how home front mobilization prioritized victory over welfare, leaving lasting scars on social cohesion and economic stability.[27]Other International Conflicts

The Italo-Turkish War, fought from September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912, pitted the Kingdom of Italy against the Ottoman Empire over control of the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in North Africa, which Italy sought to colonize as modern Libya.[41] Italian forces, numbering around 150,000 troops, invaded Tripoli on October 3, 1911, and captured key coastal cities including Tobruk, Benghazi, and Homs by late October, though Ottoman and local Arab irregulars mounted guerrilla resistance inland.[42] The conflict marked the first use of aircraft in warfare, with Italian pilots conducting aerial reconnaissance and dropping bombs on Ottoman positions starting October 23, 1911.[43] To force Ottoman capitulation, Italy extended operations to the Aegean, bombarding the Dardanelles in April 1912 and occupying the Dodecanese Islands in May, prompting international mediation.[44] The war ended with the Treaty of Ouchy (also known as the Treaty of Lausanne), under which the Ottomans ceded Libya to Italy while retaining nominal suzerainty to appease Arab populations; Italy suffered approximately 3,300 killed and 4,400 wounded, while Ottoman losses exceeded 10,000 including disease.[41] This victory weakened Ottoman control in North Africa and encouraged Balkan states to challenge Ottoman rule in Europe.[42] The First Balkan War erupted on October 8, 1912, when Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire, followed by Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece on October 17, as the Balkan League sought to expel Ottoman forces from remaining European territories including Macedonia, Thrace, and Albania.[45] The League mobilized roughly 750,000 troops against an Ottoman force of about 300,000 in the Balkans, achieving rapid advances: Bulgarian armies captured Kirk Kilisse on October 24 and advanced toward Constantinople, while Serbs took Skopje and Greeks occupied Ioannina by March 1913.[45] Ottoman defenses collapsed due to logistical failures and internal disarray, leading to armistices in December 1912 after battles like Lule Burgas, where Bulgaria inflicted heavy casualties.[46] The war concluded with the Treaty of London on May 30, 1913, stripping the Ottomans of nearly all European holdings except Eastern Thrace around Adrianople (Edirne); total casualties included over 80,000 Balkan League deaths (Bulgaria ~65,000, Serbia ~36,000, Greece ~9,500, Montenegro ~3,000) and more than 100,000 Ottoman fatalities from combat and disease.[46] Ethnic violence during the campaign displaced populations and sowed seeds for further conflict, with disputes over Macedonia's partition fueling tensions among the victors.[45] Tensions boiled over into the Second Balkan War in June 1913, as Bulgaria attacked Serbia and Greece over Macedonian territories gained in the first war, drawing in Romania and the Ottoman Empire as opportunists against Bulgaria.[47] Bulgarian forces, exhausted from prior fighting, faced a coalition that quickly reversed their gains: Romania invaded from the north capturing Silistra, Greece and Serbia pushed back in Macedonia, and Ottomans retook Adrianople on July 21, 1913.[46] The brief conflict, lasting about two months, ended with Bulgaria's defeat and the Treaty of Bucharest on August 10, 1913, which awarded most of Macedonia to Serbia and Greece, Dobruja to Romania, and southern Thrace to Bulgaria while restoring Adrianople to Ottoman control.[46] Bulgaria suffered around 30,000 casualties, with the coalition incurring fewer losses; the war's outcomes heightened Serbian power and irredentist claims, contributing to regional instability that precipitated broader European war in 1914.[47] Beyond these, lesser international engagements included the United States' occupation of Veracruz, Mexico, from April 21 to November 23, 1914, during the Mexican Revolution, where U.S. Marines seized the port to block German arms shipments to revolutionary general Victoriano Huerta, resulting in 19 American and 126 Mexican deaths before withdrawal under diplomatic pressure.[48] In the Pacific, Japan's Twenty-One Demands on China in January 1915 expanded influence in Shandong and Manchuria amid World War I distractions, though not escalating to full invasion until later. These episodes underscored imperial rivalries but paled in scale compared to the Ottoman-European clashes.Domestic Political Developments

Revolutions and Regime Changes

The 1910s marked a period of profound political upheaval, with multiple monarchies toppled and republics established amid widespread discontent over autocratic rule, economic inequality, and the strains of World War I. These revolutions reflected a global shift toward republicanism and constitutional governance, though outcomes varied from democratic experiments to authoritarian consolidations. Key events included the overthrow of long-standing dynasties in Portugal, China, Mexico, Russia, and Germany, often involving military revolts, popular uprisings, and provisional governments that struggled to stabilize power.[48][49] In Portugal, republican forces, galvanized by opposition to King Manuel II's perceived weakness and the influence of conservative monarchists, launched an insurrection on October 4, 1910. Naval bombardments of Lisbon and army defections forced the king's flight to exile on October 5, ending the Braganza dynasty after 800 years and proclaiming the First Portuguese Republic under Teófilo Braga as provisional president. The new regime promptly expelled religious orders, confiscated church property, and enacted anticlerical laws, though it faced immediate instability with over 40 governments in the following 16 years.[50] China's Xinhai Revolution began with the Wuchang Uprising on October 10, 1911, when New Army units mutinied against Qing Dynasty corruption and foreign concessions, sparking provincial secessions across southern and central China. Sun Yat-sen, leader of the revolutionary Tongmenghui alliance, returned from exile to assume the provisional presidency of the Republic of China on January 1, 1912, but yielded to Yuan Shikai to avoid civil war; the last emperor, Puyi, abdicated on February 12, 1912, formally ending over two millennia of imperial rule. This transition preserved Yuan's military dominance but sowed seeds for warlord fragmentation in the ensuing decade.[49][51] The Mexican Revolution commenced on November 20, 1910, with Francisco Madero's Plan of San Luis Potosí denouncing Porfirio Díaz's dictatorship and calling for elections; armed risings by figures like Pascual Orozco, Pancho Villa, and Emiliano Zapata compelled Díaz's resignation and exile on May 25, 1911. Madero's subsequent presidency (November 1911–February 1913) implemented modest reforms but alienated radicals, leading to his coup and assassination by General Victoriano Huerta on February 19, 1913; Huerta's regime fell in July 1914 amid U.S. intervention and Constitutionalist advances under Venustiano Carranza, whose forces captured Mexico City on August 15, 1914, though factional warfare persisted until the 1920s, claiming an estimated 1–2 million lives.[48][52] Russia experienced dual revolutions in 1917, exacerbated by World War I losses exceeding 2 million dead and food shortages. The February Revolution (March 8–16, New Style) saw Petrograd strikes escalate into mutinies, forcing Tsar Nicholas II's abdication on March 15 and the Romanov dynasty's end after 304 years; Prince Georgy Lvov formed a Provisional Government, but its continuation of the war fueled unrest. The October Revolution (November 7, New Style) involved Bolshevik seizure of Petrograd's key sites, with Vladimir Lenin proclaiming Soviet power and dissolving the Provisional Government, initiating civil war and the world's first communist state by 1922.[53] Germany's revolution unfolded in the war's final months, triggered by a Kiel naval mutiny on October 29, 1918, against suicidal orders for a final battle fleet sortie. Worker and soldier councils proliferated, prompting Kaiser Wilhelm II's abdication on November 9, 1918, and the Hohenzollern monarchy's collapse; Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert assumed chancellorship, suppressing Spartacist uprisings in January 1919 with Freikorps aid and convening the National Assembly at Weimar on February 6, 1919, to draft a republican constitution ratified in August. This transition averted immediate Bolshevik-style radicalism but left unresolved tensions contributing to later instability.[54][55]Electoral and Institutional Shifts

In the United States, the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment on April 8, 1913, marked a significant institutional shift by establishing the direct election of U.S. senators by popular vote, replacing the prior system of selection by state legislatures.[56] This change, certified on May 31, 1913, aimed to enhance democratic accountability and reduce corruption in senatorial appointments.[57] Concurrently, women's suffrage advanced at the state level, with Washington granting full voting rights to women in 1910, followed by California in 1911, Arizona, Kansas, and Oregon in 1912, and Illinois allowing presidential and municipal suffrage in 1913.[58] In the United Kingdom, the Parliament Act of 1911 fundamentally altered the balance of power between the House of Commons and the House of Lords by eliminating the Lords' veto on money bills and restricting their ability to block other legislation to a two-session or three-year delay.[59] Enacted on August 18, 1911, amid constitutional tensions following the rejection of the Liberal budget in 1909, it asserted Commons' primacy in financial matters.[60] The Representation of the People Act of 1918 extended the franchise to all men over 21 and women over 30 meeting a property qualification, expanding the electorate from about 8 million to 21 million and enfranchising approximately 8.4 million women.[61] Germany experienced electoral shifts without formal institutional overhaul, as the 1912 Reichstag election saw the Social Democratic Party (SPD) secure 4.2 million votes (34.8 percent), electing 110 deputies and becoming the largest single party in the legislature for the first time.[62] This outcome reflected growing working-class mobilization under the existing universal male suffrage system but did not alter the Prussian three-class voting restrictions that skewed outcomes toward conservatives.[63] In the Russian Empire, the June 3, 1907, electoral law revision—issued alongside the dissolution of the Second Duma—disproportionately reduced representation for peasants and workers while increasing seats for landowners, resulting in more conservative compositions for the Third Duma (1907–1912) and Fourth Duma (1912–1917).[64] This change curtailed the democratic elements introduced by the 1905 Fundamental Laws, maintaining tsarist control until the 1917 revolutions introduced provisional universal suffrage for the Constituent Assembly election in November 1917.[65]Political Violence and Assassinations

![Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria][float-right] The 1910s were marked by a surge in political assassinations, often driven by anarchist ideologies, nationalist fervor, or revolutionary discontent, contributing to global instability. On November 12, 1912, Spanish Prime Minister José Canalejas was shot dead in Madrid by anarchist Manuel Pardiñas, who subsequently took his own life; the killing was inspired by resentment over the execution of educator Francisco Ferrer.[66] In Mexico, President Francisco I. Madero and Vice President José María Pino Suárez were assassinated on February 22, 1913, during a military coup led by General Victoriano Huerta, an event known as part of the Decena Trágica that escalated the Mexican Revolution.[67] [68] King George I of Greece fell victim to assassination on March 18, 1913, while walking unguarded in Thessaloniki, shot by Alexandros Schinas, a mentally unstable individual with possible anarchist leanings; Schinas died days later, reportedly by suicide or police action.[69] The most consequential assassination occurred on June 28, 1914, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie were killed in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb nationalist affiliated with the Black Hand group, precipitating the July Crisis and the outbreak of World War I. In Russia, Grigori Rasputin, the influential mystic advisor to the imperial family, was murdered on December 30, 1916 (Old Style), by a conspiracy of nobles led by Prince Felix Yusupov, who poisoned, shot, and drowned him in an effort to curb his sway over Tsar Nicholas II amid wartime crises; autopsy confirmed death by gunshot.[70] Political violence extended beyond targeted killings, as seen in the United States where labor disputes turned deadly: the October 1, 1910, dynamite bombing of the Los Angeles Times building, attributed to union militants James McNamara and his brother John, killed 21 people and injured over 100, highlighting tensions between organized labor and anti-union publishers.[71] The decade closed with a wave of anarchist bombings in the U.S., peaking in 1919 with attacks on prominent figures including a June 2 bomb at the home of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, which killed the bomber and damaged the residence; these incidents, linked to Italian anarchists like those inspired by Luigi Galleani, fueled the First Red Scare and prompted federal crackdowns.[72] Such acts of violence reflected broader ideological clashes, including anti-capitalist radicalism and fears of Bolshevism following the 1917 Russian Revolution, though they often lacked coordination and achieved limited political aims.[73]Economic Dynamics

Pre-War Growth and Industrialization

The pre-World War I period from 1910 to 1914 marked the culmination of the Second Industrial Revolution, with sustained growth in industrial output across major economies driven by advancements in chemicals, electricity, and mass production techniques. In the United States, the annual index of industrial production, constructed from 43 quantity series, increased from 1,783.9 in 1910 to 1,975.0 in 1913, representing an average annual growth of approximately 3.4 percent amid minor fluctuations, such as a dip to 1,717.9 in 1911.[74] This expansion reflected broader manufacturing gains, including steel and machinery, fueled by immigration bolstering the industrial workforce.[75] A pivotal development occurred in the automotive sector when Henry Ford implemented the moving assembly line at his Highland Park plant on December 1, 1913, slashing Model T production time from over 12 hours to 93 minutes per vehicle.[76] This innovation drastically reduced unit costs through economies of scale, making automobiles accessible to the middle class and exemplifying efficient standardization that influenced global manufacturing.[76] Concurrently, Ford raised daily wages to $5 in January 1914, enhancing worker productivity and consumer purchasing power while tying remuneration to performance.[77] In Europe, industrial growth concentrated in high-technology sectors, with Germany emerging as a leader. By 1913, German steel production hit 18.6 million tons—three times Britain's 6.9 million tons—while iron output reached 14.8 million tons, overtaking Britain's 9.8 million.[78] Coal production in Germany had doubled since 1880, supporting expanded energy needs.[78] The chemical industry advanced significantly with the Haber-Bosch process, patented in 1910, enabling synthetic ammonia production for fertilizers and underscoring Germany's dominance in synthetic dyes and pharmaceuticals.[79] Electrical engineering matured, with incandescent bulb prices falling to one-fifth of 1880 levels by 1910 and efficiency doubling, facilitating urban electrification and traction systems like streetcars.[79] These innovations, alongside falling freight rates from steel-hulled ships and diesel engines, integrated global markets and propelled urbanization, as industrial hubs drew rural migrants.[79] Overall, pre-war industrialization laid foundations for wartime mobilization but remained vulnerable to geopolitical disruptions evident by 1914's production dip in the US index to 1,774.1.[74]Wartime Economies and Resource Mobilization

The outbreak of World War I in July 1914 compelled major belligerent powers to restructure their economies for total war, prioritizing munitions, vehicles, and supplies over civilian goods through centralized planning and state directives.[80] Industrial production in the United States, initially neutral, rose 32 percent from 1914 to 1917, with gross national product increasing nearly 20 percent, driven by exports to Allied powers.[81] In contrast, Central Powers like Germany faced severe constraints from Allied naval blockades, which restricted imports and forced reliance on domestic substitution, such as chemical processes for nitrates.[82] Labor mobilization involved conscripting millions of men, depleting agricultural and industrial workforces; in Germany, approximately 40 percent of the male agricultural labor force was redirected to military service by 1915.[80] This gap was partially filled by women, whose employment in German factories with ten or more workers grew from 1.59 million in 1913 to 2.32 million by 1918.[83] In Britain, female participation in the workforce expanded from 23.6 percent of the working-age population in 1914 to between 37.7 and 46.7 percent by 1918, enabling sustained output of artillery shells and vehicles.[84] By 1917, nearly 1.4 million German women were integrated into war-related labor, underscoring the scale of societal reconfiguration.[29] Resource allocation featured rationing systems to prioritize military needs, particularly food and fuel; Britain's formal food rationing began in February 1918, while Germany's "Turnip Winter" of 1916-1917 highlighted blockade-induced famines, with civilian calorie intake dropping below subsistence levels.[85] Governments financed these efforts mainly through borrowing, with the U.S. issuing Liberty Bonds that raised over $21 billion by 1919 to cover war costs equaling 52 percent of its gross national product.[85][86] Allied advantages in prewar industrial capacity—2.9 times that of the Central Powers—facilitated superior mobilization, producing disproportionate materiel despite comparable initial mobilizations.[87] The U.S. entry in April 1917 amplified this disparity, supplying vast munitions and raw materials that tipped production balances decisively.[88]Post-War Disruptions and Inflation

The Armistice of November 11, 1918, triggered widespread economic disruptions as governments shifted from wartime to peacetime production, leading to demobilization of millions of soldiers and abrupt declines in industrial demand. In the United States, factory employment dropped 15 percent from the third quarter of 1918 peak to the second quarter of 1919 low, contributing to a modest recession amid the reintegration of veterans into civilian labor markets.[89] Concurrently, the 1918 influenza pandemic exacerbated these shocks by reducing economic activity and amplifying inflationary pressures, resulting in substantial declines in real returns on investments.[90] Wartime fiscal policies, including deficit spending and monetary expansion, sustained high inflation into 1919 across major belligerents. In the US, consumer prices rose at an annualized rate of 18.5 percent from 1917 to 1920, with everyday goods like shoes increasing from $3 pre-war to $10–$12 by 1918, reflecting persistent supply shortages and excess liquidity.[91][92] European nations experienced similar dynamics after abandoning the gold standard, with inflation accelerating due to reconstruction needs and food/raw material scarcities; governments responded by expanding money supplies, sowing seeds for instability.[93][94] In Germany, the newly formed Weimar Republic inherited war debts and faced acute inflationary pressures from 1919 onward, as fiscal deficits and import barriers hindered recovery. The Treaty of Versailles, signed June 28, 1919, mandated reparations equivalent to 132 billion gold marks (about $33 billion at the time), straining finances and prompting monetary accommodation that devalued the mark; by late 1919, floating exchange rates further fueled price rises.[95] Economic policy uncertainty, including debates over reparations and debt monetization, elevated risks of hyperinflation in Central Europe, though full episodes emerged post-1919.[94] These disruptions, compounded by political turmoil, delayed stabilization and contributed to social unrest across the continent.Scientific and Technological Progress

Theoretical Advances in Physics

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford proposed the nuclear model of the atom based on the scattering of alpha particles by thin gold foil, concluding that atoms consist of a small, dense, positively charged nucleus containing nearly all the mass, orbited by electrons in a mostly empty space.[96] This overturned J.J. Thomson's plum pudding model and provided a framework for subsequent atomic theories, though it initially struggled to explain electron stability without radiation.[96] Building on Rutherford's nucleus, Niels Bohr introduced in 1913 a quantized model for the hydrogen atom, where electrons occupy discrete orbits with fixed angular momentum multiples of Planck's constant, preventing continuous energy loss and accounting for the atom's emission spectrum.[97] Bohr's postulates marked the onset of the "old quantum theory," reconciling classical mechanics with quantum ideas for specific systems, though it remained semi-classical and limited to hydrogen-like atoms.[98] Albert Einstein finalized the general theory of relativity in November 1915, submitting the field equations on November 25 that unify gravity with spacetime geometry, where mass-energy curves four-dimensional spacetime, predicting phenomena like the deflection of light by gravity.[99] This extended special relativity to accelerated frames and non-inertial observers, resolving inconsistencies in Newtonian gravity for high speeds and strong fields, with initial predictions verified observationally in later eclipse expeditions.[100] These advances, discussed at forums like the 1911 Solvay Conference on atomic structure, shifted physics toward probabilistic and geometric paradigms, challenging determinism and absolute space-time.[10] While experimental confirmations followed, the theoretical innovations of Rutherford, Bohr, and Einstein established core principles enduring in modern physics.[101]Engineering and Industrial Innovations

The decade saw transformative advancements in manufacturing, exemplified by Henry Ford's introduction of the moving assembly line on December 1, 1913, at the Highland Park plant in Michigan, which drastically reduced Model T production time from over 12 hours to approximately 93 minutes per vehicle and lowered costs, enabling mass affordability.[102][76] This innovation, drawing from earlier industrial practices like Chicago meatpacking, standardized tasks and worker specialization, boosting output to over 500,000 vehicles annually by 1914 and influencing global factory systems.[103] In automotive engineering, Charles Kettering's electric self-starter, patented in 1911 and first implemented in the 1912 Cadillac, replaced hazardous hand-cranking, using a compact motor to engage the flywheel and enhancing vehicle accessibility, particularly for women drivers.[104][105] By 1913, it became standard on Cadillac models, with the system operating on 24 volts for starting while integrating 6-volt lighting, marking a shift toward electrical integration in internal combustion engines.[106] World War I catalyzed military engineering breakthroughs, including the British Mark I tank, prototyped in 1915 and first deployed on September 15, 1916, at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, where its tracked design and armor enabled traversal of trenches and barbed wire, though initial mechanical unreliability limited impact until later models like the Mark V improved reliability.[107][108] Over 2,000 tanks were produced by war's end, laying groundwork for mechanized warfare.[107] Aviation progressed rapidly during the war, evolving from fragile reconnaissance biplanes in 1914 to synchronized fighter aircraft by 1917, with interrupter gears allowing machine guns to fire through propellers without damage, as in the German Fokker E.III, enabling dogfights and air dominance strategies.[109] Production scaled massively, with Allied forces fielding thousands of planes by 1918, incorporating stronger engines, maneuverable designs, and early bombsights, while seaplanes advanced naval reconnaissance.[110] Materials science advanced with Harry Brearley's 1913 development of stainless steel, a 12.8% chromium, 0.24% carbon alloy created accidentally during gun barrel erosion tests at Sheffield's Brown-Firth laboratory, offering unprecedented corrosion resistance for cutlery and industrial tools.[111] This martensitic steel, patented soon after, found wartime applications in weaponry and post-war expansion in durable goods manufacturing.[112] Industrial electrification expanded, with interconnected power grids and larger generators enabling factory scalability, while wartime demands spurred chemical engineering, such as scaled Haber-Bosch ammonia synthesis for explosives, sustaining prolonged conflict through synthetic nitrates.[11] These innovations, driven by commercial efficiency and military necessity, fundamentally reshaped production and engineering paradigms entering the 1920s.Medical and Public Health Developments

In 1910, Paul Ehrlich and Sahachiro Hata introduced Salvarsan (arsphenamine), the first synthetic chemotherapeutic agent specifically designed to combat syphilis, an arsenic-based compound that marked a breakthrough in targeted antimicrobial therapy by selectively attacking the causative spirochete Treponema pallidum.[113] This "magic bullet" approach, tested on over 10 million patients by the 1920s, reduced syphilis mortality and transmission rates, though its administration required intravenous injection and carried risks of toxicity like arsenic poisoning.[114] Ehrlich's work built on earlier organoarsenic research, emphasizing rational drug design over empirical remedies, and laid groundwork for modern pharmacology despite initial controversies over efficacy claims.[115] The Flexner Report, commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and published in 1910, catalyzed reforms in American medical education by evaluating 155 schools and recommending closure of those lacking rigorous scientific training, resulting in the shuttering of about half by 1920 and elevating standards through integration of laboratory sciences and clinical practice.[116] Authored by educator Abraham Flexner, the report privileged evidence-based curricula over proprietary or homeopathic institutions, fostering a biomedical model that prioritized empirical validation and reduced quackery, though critics noted its bias toward elite, research-oriented programs.[116] World War I accelerated blood transfusion techniques, with Belgian physician Albert Hustin demonstrating in 1914 that sodium citrate could anticoagulate blood for indirect transfusion, enabling storage and reducing clotting risks during battlefield use.[117] American pathologist Roger Lee advanced compatibility testing in the mid-1910s by refining cross-matching methods, minimizing hemolytic reactions and allowing broader application; by 1917-1918, transfusions saved thousands of soldiers from hemorrhagic shock, with British and French armies performing over 20,000 procedures.[118] These innovations, including Oswald Robertson's mobile blood depots, transitioned transfusions from rare, direct arm-to-arm methods to scalable interventions, though pre-war ABO typing by Karl Landsteiner (1901) remained foundational.[119] Wartime exigencies also spurred antiseptics and surgical advances, such as the Carrel-Dakin method (1915), which used dilute sodium hypochlorite (Dakin's solution) for continuous wound irrigation, drastically lowering infection rates in trench injuries from over 50% to under 5% in treated cases.[120] Plastic surgery pioneered by Harold Gillies in 1916 at Sidcup established reconstructive techniques for facial wounds, using tubular pedicle flaps to restore functionality and appearance in over 5,000 patients.[121] Typhoid vaccination, developed pre-war by Almroth Wright, saw mandatory implementation in Allied forces by 1914, reducing incidence from 10-20% in unvaccinated troops to near zero, via heat-killed bacterial inoculations that elicited protective antibodies.[122] The 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, caused by an H1N1 virus, infected one-third of the global population and killed 50 million, overwhelming medical systems with secondary bacterial pneumonias treatable only supportively absent antibiotics.[123] Public health responses emphasized non-pharmaceutical interventions: cities implementing early school closures, bans on public gatherings, and mask mandates saw 30-50% lower peak mortality, as quantified in U.S. analyses of 43 cities.[124] Failed vaccines targeting Haemophilus influenzae (misidentified as the agent) underscored virological gaps, yet the crisis advanced epidemiology, with contact tracing and quarantine protocols informing future preparedness; U.S. deaths exceeded 675,000, disproportionately affecting young adults via cytokine storms.[125] Vitamin D isolation from cod-liver oil in 1917 supported rickets prevention campaigns, linking deficiency to public health initiatives in urban slums.[126]Social Transformations

Demographic Shifts and Migrations