Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nonchord tone

View on Wikipedia

A nonchord tone (NCT), nonharmonic tone, or embellishing tone is a note in a piece of music or song that is not part of the implied or expressed chord set out by the harmonic framework. In contrast, a chord tone is a note that is a part of the functional chord. Nonchord tones are most often discussed in the context of the common practice period of classical music, but the term can also be used in the analysis of other types of tonal music, such as Western popular music.

Nonchord tones are often categorized as accented non-chord tones and unaccented non-chord tones depending on whether the dissonance occurs on an accented or unaccented beat (or part of a beat).

Over time, some musical styles assimilated chord types outside of the common-practice style. In these chords, tones that might normally be considered nonchord tones are viewed as chord tones, such as the seventh of a minor seventh chord. For example, in 1940s-era bebop jazz, an F♯ played with a C 7 chord would be considered a chord tone if the chord were analyzed as C7(♯11). In European classical music, "[t]he greater use of dissonance from period to period as a result of the dialectic of linear/vertical forces led to gradual normalization of ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords [in analysis and theory]; each additional non-chord tone above the foundational triad became frozen into the chordal mass."[2]

Theory

[edit]

Chord and nonchord tones are defined by their membership (or lack of membership) in a chord: "The pitches which make up a chord are called chord-tones: any other pitches are called non-chord-tones."[3] They are also defined by the time at which they sound: "Nonharmonic tones are pitches that sound along with a chord but are not chord pitches."[4] For example, if an excerpt from a piece of music implies or uses a C-major chord, then the notes C, E and G are members of that chord, while any other note played at that time (e.g., notes such as F♯) is a nonchord tone. Such tones are most obvious in homophonic music but occur at least as frequently in contrapuntal music.

According to Music in Theory and Practice, "Most nonharmonic tones are dissonant and create intervals of a second, fourth or seventh",[4] which are required to resolve to a chord tone in conventional ways. If the note fails to resolve until the next change of harmony, it may instead create a seventh chord or extended chord. While theoretically in a three-note chord, there are nine possible nonchord tones in equal temperament, in practice nonchord tones are usually in the prevailing key. Augmented and diminished intervals are also considered dissonant, and all nonharmonic tones are measured from the bass note, or lowest note sounding in the chord except in the case of nonharmonic bass tones.[4]

Nonharmonic tones generally occur in a pattern of three pitches, of which the nonharmonic tone is the center:[4]

Chord tone – Nonchord tone – Chord tone Preparation – Dissonance – Resolution

Nonchord tones are categorized by how they are used. The most important distinction is whether they occur on a strong or weak beat and are thus either accented or unaccented nonchord tones.[4] They are also distinguished by their direction of approach and departure and the voice or voices in which they occur and the number of notes they contain.

Unaccented

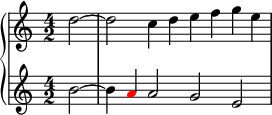

[edit]Anticipation

[edit]An anticipation (ANT) occurs when this note is approached by step and then remains the same. It is basically a note of the second chord played early. In the example below, the dissonant B in bar 1 is approached by step and resolves when that same pitch becomes a chord tone in bar 2.

A portamento is the late Renaissance precursor to the anticipation,[5] though today it refers to a glissando.

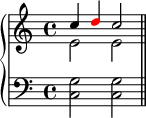

Neighbor tone

[edit]A neighbor tone (NT) or auxiliary note (AUX) is a nonchord tone that passes stepwise from a chord tone directly above or below it (which frequently causes the NT to create dissonance with the chord) and resolves to the same chord tone:

In practice and analysis, neighboring tones are sometimes differentiated depending upon whether or not they are lower or higher than the chord tones surrounding them. A neighboring tone that is a step higher than the surrounding chord tones is called an upper neighboring tone or an upper auxiliary note while a neighboring tone that is a step lower than the surrounding chord tones is a lower neighboring tone or lower auxiliary note. However, following Heinrich Schenker's usage in Free Composition, some authors reserve the term "neighbor note" to the lower neighbor a half step below the main note.[6]

The German term Nebennote is a somewhat broader category, including all nonchord tones approached from the main note by step.[6]

Escape tone

[edit]An escape tone (ET) or echappée is a particular type of unaccented incomplete neighbor tone that is approached stepwise from a chord tone and resolved by a skip in the opposite direction back to the harmony.

Passing tone

[edit]A passing tone (PT) or passing note is a nonchord tone prepared by a chord tone a step above or below it and resolved by continuing in the same direction stepwise to the next chord tone (which is either part of the same chord or of the next chord in the harmonic progression).

Where two nonchord tones are before the resolution they are double passing tones or double passing notes.

Accented non-chord tones

[edit]Passing tone

[edit]A tone that sits between two chord tones and is between them.

Neighbor tone

[edit]A neighbour tone is where there is a step up or down from a note (or chord tone) and then move back to the original note.[7]

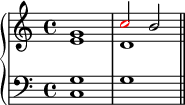

Suspension and retardation

[edit]

Endeavor, moreover, to introduce suspensions now in this voice, now in that, for it is incredible how much grace the melody acquires by this means. And every note which has a special function is rendered audible thereby.

— Johann Joseph Fux (1725)[8]

A suspension (SUS) (sometimes referred to as a syncope)[9] occurs when the harmony shifts from one chord to another, but one or more notes of the first chord (the preparation) are either temporarily held over into or are played again against the following chord (against which they are nonchord tones called the suspension) before resolving downwards to a chord tone by step (the resolution). The whole process is called a suspension as well as the specific nonchord tone(s).

Suspensions may be further described with two numbers: (1) the interval between the suspended note and the bass note and (2) the interval between the resolution and the bass note. The most common suspensions are 4–3 suspension, 7–6 suspension, or 9–8 suspension. Note that except for the 9–8 suspensions, the numbers are typically referred to using the simple intervals, so for instance, if the intervals are actually an 11th and a 10th (the first example below), one would typically call it a 4–3 suspension. If the bass note is suspended, then the interval is calculated between the bass and the part that is most dissonant with it, often resulting in a 2–3 suspension.[10]

Suspensions must resolve downwards. If a tied note is prepared like a suspension but resolves upwards, it is called a retardation. Common retardations include 2–3 and 7–8 retardations.

Decorated suspensions are common and consist of portamentos or double eighth notes, the second being a lower neighbor tone.

A chain of suspensions constitutes the fourth species of counterpoint; an example may be found in the second movement of Corelli's Christmas Concerto.

Appoggiatura

[edit]An appoggiatura (APP) is a type of accented incomplete neighbor tone approached skip-wise from one chord tone and resolved stepwise to another chord tone ("overshooting" the chord tone).

Nonharmonic bass

[edit]Nonharmonic bass notes are bass notes that are not a member of the chord below which they are written. Examples include the Elektra chord.[11] An example of a nonharmonic bass from the third movement of Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms.[12]

Involving more than three notes

[edit]Changing tones

[edit]Changing tones (CT) are two successive nonharmonic tones. A chord tone steps to a nonchord tone which skips to another nonchord tone which leads by step to a chord tone, often the same chord tone. They may imply neighboring tones with a missing or implied note in the middle. Also called double neighboring tones or neighbor group.[4]

Pedal point

[edit]Another form of nonchord tone is a pedal point or pedal tone (PD) or note, almost always the tonic or dominant, which is held through a series of chord changes. The pedal point is almost always in the lowest voice (the term originates from organ playing), but it may be in an upper voice; then it may be called an inverted pedal. It may also be between the upper and lower voices, in which case it is called an internal pedal.

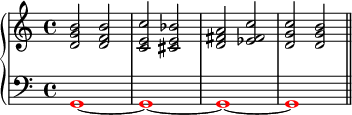

Chromatic nonharmonic tone

[edit]A chromatic nonharmonic tone is a nonharmonic tone that is chromatic, or outside of the key and creates half-step motion. The use of which, especially chromatic appoggiaturas and chromatic passing tones, increased in the Romantic Period.[13] The example below shows chromatic nonharmonic tones (in red) in the first four measures of Chopin's Prelude No. 21, op. 28.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kostka & Payne (2004), p. 189.

- ^ Roland Nadeau (September 1979). "Debussy and the Crisis of Tonality". Music Educators Journal. 66 (1): 72 (69–73). doi:10.2307/3395721. JSTOR 3395721.

- ^ Kroepel, Bob (1993). Mel Bay Creative Keyboard's Deluxe Encyclopedia of Piano Chords: A Complete Study of Chords and How to Use Them, p. 8. ISBN 978-0-87166-579-9. Emphasis original.

- ^ a b c d e f Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p. 92. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn Nadine (2009). Music in Theory and Practice. Vol. II (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- ^ a b Drabkin, William (2001). "Non-harmonic note". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.20039. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription required)

- ^ "Nonharmonic Tones".

- ^ Forte 1979, p. 304.

- ^ Jonas 1982, p. 96.

- ^ Kostka & Payne 2004, p. 172.

- ^ Lawrence Kramer. "Fin-de-siècle Fantasies: Elektra, Degeneration and Sexual Science", Cambridge Opera Journal, vol. 5, no. 2. (July 1993), pp. 141–165.

- ^ Andriessen, Louis & Schönberger, Elmer (2006). The Apollonian Clockwork: On Stravinsky. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053568569.

- ^ a b Benward & Saker (2009), pp. 217–218

Sources

- Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony (3rd ed.). Holt, Rinehart, and Wilson. ISBN 0-03-020756-8.

- Jonas, Oswald (1982). Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker (translation of Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einführung in die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers (1934)). Translated by John Rothgeb. Longman. ISBN 0-582-28227-6.

- Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy (2004). Tonal Harmony (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0072852607. OCLC 51613969.

External links

[edit] Media related to Nonchord tones at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nonchord tones at Wikimedia Commons

![{

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative c'' {

\tempo "Cantabile"

\clef treble \key bes \major \time 3/4

\override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #2.5

f2.\p( d2 \acciaccatura { f8 } es4 d2. g,2.)

}

>>

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative c {

\clef bass \key bes \major \time 3/4

\override NoteHead.color = #red \hide Stem s4 e8 s4.

s4 e8 s4.

s4 fis8 b s4

s4 fis8 b s4

}

\new Voice \relative c, {

\clef bass \key bes \major \time 3/4

bes8\<\sustainOn_[ f''^( <e g>\sustainOff <es a> <d bes'> <c c'>]\!

bes8\<\sustainOn_[) <f' d'>^( <e g>\sustainOff <es a> <d bes'> bes]\!

es,8\<\sustainOn_[) g'^( <fis a>\sustainOff <f b> <es c'> <d d'>]\!

c8\<\sustainOn_[) <g' es'>^( <fis a>\sustainOff <f b> <es c'> <c es'>])\!

}

>>

>> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/c/tcjekb1ivlqux7kmvgn3ndd0od59g6c/tcjekb1i.png)