Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Musical note

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

In music, notes are distinct and isolatable sounds that act as the most basic building blocks for nearly all of music. This discretization facilitates performance, comprehension, and analysis.[1] Notes may be visually communicated by writing them in musical notation.

Notes can distinguish the general pitch class or the specific pitch played by a pitched instrument. Although this article focuses on pitch, notes for unpitched percussion instruments distinguish between different percussion instruments (and/or different manners to sound them) instead of pitch. Note value expresses the relative duration of the note in time. Dynamics for a note indicate how loud to play them. Articulations may further indicate how performers should shape the attack and decay of the note and express fluctuations in a note's timbre and pitch. Notes may even distinguish the use of different extended techniques by using special symbols.

The term note can refer to a specific musical event, for instance when saying the song "Happy Birthday to You", begins with two notes of identical pitch. Or more generally, the term can refer to a class of identically sounding events, for instance when saying "the song begins with the same note repeated twice".

Distinguishing duration

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2024) |

A note can have a note value that indicates the note's duration relative to the musical meter. In order of halving duration, these values are:

| "American" name | "British" name | |

|---|---|---|

| double note | breve | |

| whole note | semibreve | |

| half note | minim | |

| quarter note | crotchet | |

| eighth note | quaver | |

| sixteenth note | semiquaver | |

| thirty-second note | demisemiquaver | |

| sixty-fourth note | hemidemisemiquaver | |

| 𝅘𝅥𝅲 | hundred twenty-eighth note | semihemidemisemiquaver, quasihemidemisemiquaver |

Longer note values (e.g. the longa) and shorter note values (e.g. the two hundred fifty-sixth note) do exist, but are very rare in modern times. These durations can further be subdivided using tuplets.

A rhythm is formed from a sequence in time of consecutive notes (without particular focus on pitch) and rests (the time between notes) of various durations.

Distinguishing pitch

[edit]

Distinguishing pitches of a scale

[edit]Music theory in most European countries and others[note 1] use the solfège naming convention. Fixed do uses the syllables re–mi–fa–sol–la–ti specifically for the C major scale, while movable do labels notes of any major scale with that same order of syllables.

Alternatively, particularly in English- and some Dutch-speaking regions, pitch classes are typically represented by the first seven letters of the Latin alphabet (A, B, C, D, E, F and G), corresponding to the A minor scale. Several European countries, including Germany and Czechia, use H instead of B (see § 12-tone chromatic scale for details). Byzantium used the names Pa–Vu–Ga–Di–Ke–Zo–Ni (Πα–Βου–Γα–Δι–Κε–Ζω–Νη).[2]

In traditional Indian music, musical notes are called svaras and commonly represented using the seven notes, Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha and Ni.

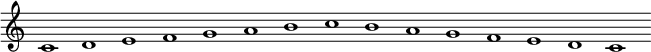

Writing notes on a staff

[edit]In a score, each note is assigned a specific vertical position on a staff position (a line or space) on the staff, as determined by the clef. Each line or space is assigned a note name. These names are memorized by musicians and allow them to know at a glance the proper pitch to play on their instruments.

The staff above shows the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C and then in reverse order, with no key signature or accidentals.

Accidentals

[edit]Notes that belong to the diatonic scale relevant in a tonal context are called diatonic notes. Notes that do not meet that criterion are called chromatic notes or accidentals. Accidental symbols visually communicate a modification of a note's pitch from its tonal context. Most commonly,[note 2] the sharp symbol (♯) raises a note by a half step, while the flat symbol (♭) lowers a note by a half step. This half step interval is also known as a semitone (which has an equal temperament frequency ratio of 12√2 ≅ 1.0595). The natural symbol (♮) indicates that any previously applied accidentals should be cancelled. Advanced musicians use the double-sharp symbol (![]() ) to raise the pitch by two semitones, the double-flat symbol (

) to raise the pitch by two semitones, the double-flat symbol (![]() ) to lower it by two semitones, and even more advanced accidental symbols (e.g. for quarter tones). Accidental symbols are placed to the right of a note's letter when written in text (e.g. F♯ is F-sharp, B♭ is B-flat, and C♮ is C natural), but are placed to the left of a note's head when drawn on a staff.

) to lower it by two semitones, and even more advanced accidental symbols (e.g. for quarter tones). Accidental symbols are placed to the right of a note's letter when written in text (e.g. F♯ is F-sharp, B♭ is B-flat, and C♮ is C natural), but are placed to the left of a note's head when drawn on a staff.

Systematic alterations to any of the 7 lettered pitch classes are communicated using a key signature. When drawn on a staff, accidental symbols are positioned in a key signature to indicate that those alterations apply to all occurrences of the lettered pitch class corresponding to each symbol's position. Additional explicitly-noted accidentals can be drawn next to noteheads to override the key signature for all subsequent notes with the same lettered pitch class in that bar. However, this effect does not accumulate for subsequent accidental symbols for the same pitch class.

12-tone chromatic scale

[edit]Assuming enharmonicity, accidentals can create pitch equivalences between different notes (e.g. the note B♯ represents the same pitch as the note C). Thus, a 12-note chromatic scale adds 5 pitch classes in addition to the 7 lettered pitch classes.

The following chart lists names used in different countries for the 12 pitch classes of a chromatic scale built on C. Their corresponding symbols are in parentheses. Differences between German and English notation are highlighted in bold typeface. Although the English and Dutch names are different, the corresponding symbols are identical.

| English | C | C sharp (C♯) |

D | D sharp (D♯) |

E | F | F sharp (F♯) |

G | G sharp (G♯) |

A | A sharp (A♯) |

B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D flat (D♭) |

E flat (E♭) |

G flat (G♭) |

A flat (A♭) |

B flat (B♭) | ||||||||

| German[3][note 3] | C | Cis (C♯) |

D | Dis (D♯) |

E | F | Fis (F♯) |

G | Gis (G♯) |

A | Ais (A♯) |

H |

| Des (D♭) |

Es (E♭) |

Ges (G♭) |

As (A♭) |

B | ||||||||

| Swedish compromise[4] | C | Ciss (C♯) |

D | Diss (D♯) |

E | F | Fiss (F♯) |

G | Giss (G♯) |

A | Aiss (A♯) |

H |

| Dess (D♭) |

Ess (E♭) |

Gess (G♭) |

Ass (A♭) |

Bess (B♭) | ||||||||

| Dutch[3][note 4] | C | Cis (C♯) |

D | Dis (D♯) |

E | F | Fis (F♯) |

G | Gis (G♯) |

A | Ais (A♯) |

B |

| Des (D♭) |

Es (E♭) |

Ges (G♭) |

As (A♭) |

Bes (B♭) | ||||||||

| Romance languages[5][note 5] | do | do diesis (do♯) |

re | re diesis (re♯) |

mi | fa | fa diesis (fa♯) |

sol | sol diesis (sol♯) |

la | la diesis (la♯) |

si |

| re bemolle (re♭) |

mi bemolle (mi♭) |

sol bemolle (sol♭) |

la bemolle (la♭) |

si bemolle (si♭) | ||||||||

| Byzantine[6] | Ni | Ni diesis | Pa | Pa diesis | Vu | Ga | Ga diesis | Di | Di diesis | Ke | Ke diesis | Zo |

| Pa hyphesis | Vu hyphesis | Di hyphesis | Ke hyphesis | Zo hyphesis | ||||||||

| Japanese[7] | Ha (ハ) | Ei-ha (嬰ハ) |

Ni (ニ) | Ei-ni (嬰ニ) |

Ho (ホ) | He (ヘ) | Ei-he (嬰へ) |

To (ト) | Ei-to (嬰ト) |

I (イ) | Ei-i (嬰イ) |

Ro (ロ) |

| Hen-ni (変ニ) |

Hen-ho (変ホ) |

Hen-to (変ト) |

Hen-i (変イ) |

Hen-ro (変ロ) | ||||||||

| Hindustani Indian[8] | Sa (सा) |

Re Komal (रे॒) |

Re (रे) |

Ga Komal (ग॒) |

Ga (ग) |

Ma (म) |

Ma Tivra (म॑) |

Pa (प) |

Dha Komal (ध॒) |

Dha (ध) |

Ni Komal (नि॒) |

Ni (नि) |

| Carnatic Indian | Sa | Shuddha Ri (R1) | Chatushruti Ri (R2) | Sadharana Ga (G2) | Antara Ga (G3) | Shuddha Ma (M1) | Prati Ma (M2) | Pa | Shuddha Dha (D1) | Chatushruti Dha (D2) | Kaisika Ni (N2) | Kakali Ni (N3) |

| Shuddha Ga (G1) | Shatshruti Ri (R3) | Shuddha Ni (N1) | Shatshruti Dha (D3) | |||||||||

| Bengali Indian[9] | Sa (সা) |

Komôl Re (ঋ) |

Re (রে) |

Komôl Ga (জ্ঞ) |

Ga (গ) |

Ma (ম) |

Kôṛi Ma (হ্ম) |

Pa (প) |

Komôl Dha (দ) |

Dha (ধ) |

Komôl Ni (ণ) |

Ni (নি) |

Distinguishing pitches of different octaves

[edit]Two pitches that are any number of octaves apart (i.e. their fundamental frequencies are in a ratio equal to a power of two) are perceived as very similar. Because of that, all notes with these kinds of relations can be grouped under the same pitch class and are often given the same name.

The top note of a musical scale is the bottom note's second harmonic and has double the bottom note's frequency. Because both notes belong to the same pitch class, they are often called by the same name. That top note may also be referred to as the "octave" of the bottom note, since an octave is the interval between a note and another with double frequency.

Scientific versus Helmholtz pitch notation

[edit]Two nomenclature systems for differentiating pitches that have the same pitch class but which fall into different octaves are:

- Helmholtz pitch notation, which distinguishes octaves using prime symbols and letter case of the pitch class letter.

- The octave below tenor C is called the "great" octave. Notes in it and are written as upper case letters.

- The next lower octave is named "contra". Notes in it include a prime symbol below the note's letter.

- Names of subsequent lower octaves are preceded with "sub". Notes in each include an additional prime symbol below the note's letter.

- The octave starting at tenor C is called the "small" octave. Notes in it are written as lower case letters, so tenor C itself is written c in Helmholtz notation.

- The next higher octave is called "one-lined". Notes in it include a prime symbol above the note's letter, so middle C is written c′.

- Names of subsequently higher octaves use higher numbers before the "lined". Notes in each include an addition prime symbol above the note's letter.

- The octave below tenor C is called the "great" octave. Notes in it and are written as upper case letters.

- Scientific pitch notation, where a pitch class letter (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) is followed by a subscript Arabic numeral designating a specific octave.

- Middle C is named C4 and is the start of the 4th octave.

- Higher octaves use successively higher number and lower octaves use successively lower numbers.

- The lowest note on most pianos is A0, the highest is C8.

- Middle C is named C4 and is the start of the 4th octave.

For instance, the standard 440 Hz tuning pitch is named A4 in scientific notation and instead named a′ in Helmholtz notation.

Meanwhile, the electronic musical instrument standard called MIDI doesn't specifically designate pitch classes, but instead names pitches by counting from its lowest note: number 0 (C−1 ≈ 8.1758 Hz); up chromatically to its highest: number 127 (G9 ≈ 12,544 Hz). (Although the MIDI standard is clear, the octaves actually played by any one MIDI device don't necessarily match the octaves shown below, especially in older instruments.)

Comparison of pitch naming conventions over different octaves Helmholtz notation 'Scientific'

note

namesLatin notation MIDI

note

numbersFrequency of

that octave's A

(in Hertz)Frequency of

that octave's C

(in Hertz)octave name note names sub-subcontra C„‚ – B„‚ C−1 – B−1 Do−2 – Si−2 0 – 11 13.75 8.176 sub-contra C„ – B„ C0 – B0 Do−1 – Si−1 12 – 23 27.5 16.352 contra C‚ – B‚ C1 – B1 Do0 – Si0 24 – 35 55 32.703 great C – B C2 – B2 Do1 – Si1 36 – 47 110 65.406 small c – b C3 – B3 Do2 – Si2 48 – 59 220 130.813 one-lined c′ – b′ C4 – B4 Do3 – Si3 60 – 71 440 261.626 two-lined c″ – b″ C5 – B5 Do4 – Si4 72 – 83 880 523.251 three-lined c‴ – b‴ C6 – B6 Do5 – Si5 84 – 95 1 760 1046.502 four-lined c⁗ – b⁗ C7 – B7 Do6 – Si6 96 – 107 3 520 2093.005 five-lined c″‴ – b″‴ C8 – B8 Do7 – Si7 108 – 119 7 040 4186.009 six-lined c″⁗ – b″⁗ C9 – B9 Do8 – Si8 120 – 127

(ends at G9)14 080 8372.018

Pitch frequency in hertz

[edit]Pitch is associated with the frequency of physical oscillations measured in hertz (Hz) representing the number of these oscillations per second. While notes can have any arbitrary frequency, notes in more consonant music tends to have pitches with simpler mathematical ratios to each other.

Western music defines pitches around a central reference "concert pitch" of A4, currently standardized as 440 Hz. Notes played in tune with the 12 equal temperament system will be an integer number of half-steps above (positive ) or below (negative ) that reference note, and thus have a frequency of:

Octaves automatically yield powers of two times the original frequency, since can be expressed as when is a multiple of 12 (with being the number of octaves up or down). Thus the above formula reduces to yield a power of 2 multiplied by 440 Hz:

Logarithmic scale

[edit]

The base-2 logarithm of the above frequency–pitch relation conveniently results in a linear relationship with or :

When dealing specifically with intervals (rather than absolute frequency), the constant can be conveniently ignored, because the difference between any two frequencies and in this logarithmic scale simplifies to:

Cents are a convenient unit for humans to express finer divisions of this logarithmic scale that are 1⁄100th of an equally-tempered semitone. Since one semitone equals 100 cents, one octave equals 12 ⋅ 100 cents = 1200 cents. Cents correspond to a difference in this logarithmic scale, however in the regular linear scale of frequency, adding 1 cent corresponds to multiplying a frequency by 1200√2 (≅ 1.000578).

MIDI

[edit]For use with the MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) standard, a frequency mapping is defined by:

where is the MIDI note number. 69 is the number of semitones between C−1 (MIDI note 0) and A4.

Conversely, the formula to determine frequency from a MIDI note is:

Pitch names and their history

[edit]This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may only interest a particular audience. (November 2023) |

Music notation systems have used letters of the alphabet for centuries. The 6th century philosopher Boethius is known to have used the first fourteen letters of the classical Latin alphabet (the letter J did not exist until the 16th century),

- A B C D E F G H I K L M N O

to signify the notes of the two-octave range that was in use at the time[10] and in modern scientific pitch notation are represented as

- A2 B2 C3 D3 E3 F3 G3 A3 B3 C4 D4 E4 F4 G4

Though it is not known whether this was his devising or common usage at the time, this is nonetheless called Boethian notation. Although Boethius is the first author known to use this nomenclature in the literature, Ptolemy wrote of the two-octave range five centuries before, calling it the perfect system or complete system – as opposed to other, smaller-range note systems that did not contain all possible species of octave (i.e., the seven octaves starting from A, B, C, D, E, F, and G). A modified form of Boethius' notation later appeared in the Dialogus de musica (ca. 1000) by Pseudo-Odo, in a discussion of the division of the monochord.[11]

Following this, the range (or compass) of used notes was extended to three octaves, and the system of repeating letters A–G in each octave was introduced, these being written as lower-case for the second octave (a–g) and double lower-case letters for the third (aa–gg). When the range was extended down by one note, to a G, that note was denoted using the Greek letter gamma (Γ), the lowest note in Medieval music notation.[citation needed] (It is from this gamma that the French word for scale, gamme derives,[citation needed][12] and the English word gamut, from "gamma-ut".[13])

The remaining five notes of the chromatic scale (the black keys on a piano keyboard) were added gradually; the first being B♭, since B was flattened in certain modes to avoid the dissonant tritone interval. This change was not always shown in notation, but when written, B♭ (B flat) was written as a Latin, cursive "𝒷", and B♮ (B natural) a Gothic script (known as Blackletter) or "hard-edged" 𝔟. These evolved into the modern flat (♭) and natural (♮) symbols respectively. The sharp symbol arose from a ƀ (barred b), called the "cancelled b".[citation needed]

B♭, B and H

[edit]In parts of Europe, including Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, Norway, Denmark, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Finland, and Iceland (and Sweden before the 1990s), the Gothic 𝔟 transformed into the letter h (possibly for hart, German for "harsh", as opposed to blatt, German for "planar", or just because the Gothic 𝔟 and 𝔥 resemble each other). Therefore, in current German music notation, H is used instead of B♮ (B natural), and B instead of B♭ (B flat). Occasionally, music written in German for international use will use H for B natural and Bb for B flat (with a modern-script lower-case b, instead of a flat sign, ♭).[citation needed] Since a Bes or B♭ in Northern Europe (notated B![]() in modern convention) is both rare and unorthodox (more likely to be expressed as Heses), it is generally clear what this notation means.

in modern convention) is both rare and unorthodox (more likely to be expressed as Heses), it is generally clear what this notation means.

System "do–re–mi–fa–sol–la–si"

[edit]In Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, French, Romanian, Greek, Albanian, Russian, Mongolian, Flemish, Persian, Arabic, Hebrew, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Turkish and Vietnamese the note names are do–re–mi–fa–sol–la–si rather than C–D–E–F–G–A–B. These names follow the original names reputedly given by Guido d'Arezzo, who had taken them from the first syllables of the first six musical phrases of a Gregorian chant melody Ut queant laxis, whose successive lines began on the appropriate scale degrees. These became the basis of the solfège system. For ease of singing, the name ut was largely replaced by do (most likely from the beginning of Dominus, "Lord"), though ut is still used in some places. It was the Italian musicologist and humanist Giovanni Battista Doni (1595–1647) who successfully promoted renaming the name of the note from ut to do. For the seventh degree, the name si (from Sancte Iohannes, St. John, to whom the hymn is dedicated), though in some regions the seventh is named ti (again, easier to pronounce while singing).[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Solfège is used in Albania, Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, most Latin American countries, Arabic-speaking and Persian-speaking countries.

- ^ Another style of notation, rarely used in English, uses the suffix "is" to indicate a sharp and "es" (only "s" after A and E) for a flat (e.g. Fis for F♯, Ges for G♭, Es for E♭). This system first arose in Germany and is used in almost all European countries whose main language is not English, Greek, or a Romance language (such as French, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and Romanian). In most countries using these suffixes, the letter H is used to represent what is B natural in English, the letter B is used instead of B♭, and Heses (i.e., H𝄫) is used instead of B𝄫 (although Bes and Heses both denote the English B𝄫). Dutch-speakers in Belgium and the Netherlands use the same suffixes, but applied throughout to the notes A to G, so that B, B♭ and B have the same meaning as in English, although they are called B, Bes, and Beses instead of B, B flat and B double flat. Denmark also uses H, but uses Bes instead of Heses for B𝄫.

- ^ used in Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Norway, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden.

- ^ used in the Netherlands, and sometimes in Scandinavia after the 1990s, and Indonesia.

- ^ used in Italy (diesis/bemolle are Italian spellings), France, Spain, Romania, Russia, Latin America, Greece, Israel, Turkey, Latvia and many other countries.

References

[edit]- ^ Nattiez 1990, p. 81, note 9.

- ^ Savas I. Savas (1965). Byzantine Music in Theory and in Practice. Translated by Nicholas Dufault. Hercules Press.

- ^ a b -is = sharp; -es (after consonant) and -s (after vowel) = flat

- ^ -iss = sharp; -ess (after consonant) and -ss (after vowel) = flat

- ^ diesis = sharp; bemolle = flat

- ^ diesis (or diez) = sharp; hyphesis = flat

- ^ 嬰 (ei) = ♯ (sharp); 変 (hen) = ♭ (flat)

- ^ According to Bhatkhande Notation. Tivra = ♯ (sharp); Komal = ♭ (flat)

- ^ According to Akarmatrik Notation (আকারমাত্রিক স্বরলিপি). Kôṛi = ♯ (sharp); Komôl = ♭ (flat)

- ^ Boethius, A.M.S. [[scores:De institutione musica (Boëthius, Anicius Manlius Severinus) |De institutione musica]]: text at the International Music Score Library Project. Gottfried Friedlein Boethius. Book IV, chapter 14, page 341.

- ^ Browne, Alma Colk (1979). Medieval letter notations: A survey of the sources (Ph.D. thesis). Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois.

- ^ Pick, Edward (1869). An Etymological Dictionary Of The French Language. John Murray.

- ^ Owens, Jessie Ann (2012). "Review of The Renaissance Reform of Medieval Music Theory: Guido of Arezzo between Myth and History". Speculum. 87 (3): 906–908. ISSN 0038-7134.

Bibliography

[edit]- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990) [1987]. Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music [Musicologie générale et sémiologie]. Translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02714-5.

External links

[edit]- Converter: Frequencies to note name, ± cents

- Note names, keyboard positions, frequencies and MIDI numbers

- Music notation systems − Frequencies of equal temperament tuning – The English and American system versus the German system

- Frequencies of musical notes

- Learn How to Read Sheet Music

- Free music paper for printing and downloading

Musical note

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Musical Notes

Definition and role in music

A musical note is an abstract representation of a discrete sound in music, primarily characterized by its pitch—the perceived highness or lowness of the tone—and duration, the length of time the sound is sustained. As the most basic building block of musical expression, a note encapsulates these attributes to form the foundational elements of auditory art, allowing for the organization of sound into coherent patterns. While timbre (the unique quality or color of the sound produced by different instruments or voices) and intensity (the loudness or dynamic level) may sometimes accompany a note, they are typically considered supplementary rather than core definitional features in standard music theory.[4][7] In musical practice, notes fulfill essential roles in constructing melodies, harmonies, and rhythms, serving as the atomic units that enable composition, performance, and analysis. A melody emerges from a sequence of notes arranged in varying pitches and durations, creating a linear flow that conveys emotion or narrative, as seen in a simple ascending line like do-re-mi that outlines a basic tune. Harmonies arise when multiple notes sound simultaneously, forming chords that provide vertical depth and support to the melody—for instance, a single note such as G might function alone in a sparse phrase or integrate into a G major triad (G-B-D) to enrich texture. Rhythms, meanwhile, derive from the temporal relationships between note durations, patterning the pulse and groove of a piece. These roles underscore the note's versatility across musical genres, from orchestral works to popular songs.[4][7] Composers manipulate notes to craft intricate structures, performers interpret them to infuse personal expression, and analysts dissect them to reveal underlying principles of form and style. By isolating and combining notes, musicians achieve clarity in intent, whether emphasizing a poignant solo note in a ballad or layering them in polyphonic ensembles. This foundational function persists universally in music-making, adapting to diverse cultural contexts while rooted in the interplay of pitch and duration as key attributes.[4][7]Basic elements: Pitch and duration

A musical note's pitch refers to the subjective perception of its highness or lowness, which arises from the auditory system's interpretation of the sound's periodic waveform.[8] This perception is primarily determined by the fundamental frequency, the lowest frequency component in the sound wave that establishes its overall periodicity, akin to the repetition rate of a simple oscillating waveform.[9] Unlike an interval, which describes the relational difference in pitch between two distinct notes, pitch itself pertains to the absolute quality of a single tone.[10] The duration of a musical note denotes the length of time for which it is sustained or sounded, measured relative to the prevailing tempo and meter of the composition.[11] Basic durations include the whole note, which occupies a full measure in common time; the half note, equivalent to half that length; and the quarter note, half again of the half note, forming the foundational subdivisions in Western music theory.[12] Pitch and duration interrelate to form the temporal and melodic structure of music, where a sequence of pitches varying over durations creates rhythmic lines and harmonic progressions, much as the steady oscillation of a waveform conveys a sustained tone's continuity.[6] This combination allows notes to contribute to both vertical harmony and horizontal melody, independent yet complementary elements in musical expression.[13]Notation Systems

Staff notation for pitch

The musical staff, also known as the stave, is a fundamental component of Western music notation, consisting of five horizontal lines and the four spaces between them, which together provide a visual framework for representing pitch.[2] These lines and spaces are arranged vertically, with pitches ascending from bottom to top, allowing composers and performers to denote relative heights of notes corresponding to their frequencies.[6] A clef is placed at the beginning of the staff to specify the pitch range and assign specific notes to particular lines or spaces. The treble clef, also called the G clef, curls around the second line from the bottom to indicate that it represents the pitch G above middle C, making it suitable for higher ranges such as those used in vocal soprano parts or instruments like the violin.[14] The bass clef, or F clef, positions its two dots on either side of the fourth line from the bottom to denote F below middle C, commonly employed for lower ranges in vocal bass lines or instruments like the cello.[15] The alto clef, a C clef that centers its middle mark on the third line to indicate middle C, is typically used for viola parts and certain vocal scores to bridge middle registers.[14] Notes are placed on the lines or in the spaces of the staff to indicate pitches within a diatonic scale, with each successive position representing the next stepwise interval. For instance, in the treble clef, the bottom line corresponds to E, the space above it to F, the second line to G, and so on up to the top space for F in the octave above middle C.[16] Ledger lines, short horizontal extensions added above or below the staff, enable the notation of pitches that fall outside the standard five-line range, such as high Cs above the treble staff or low As below the bass staff, ensuring comprehensive representation without altering the core structure.[17] The modern five-line staff evolved from earlier notational systems in 11th-century Europe, where the monk Guido d'Arezzo advanced the use of a four-line staff derived from neumes—simple symbols indicating melodic direction—to precisely fix pitches on lines for easier sight-reading by choirs.[18] This innovation, detailed in Guido's treatise Micrologus around 1026, laid the groundwork for the standardized staff system still in use today, transforming music education and composition.[19]Symbols for duration and rhythm

In musical notation, symbols for duration and rhythm represent the temporal length of notes and their organization within a metrical framework, distinguishing them from pitch elements.[20] The primary symbols for note durations form a hierarchical system based on binary subdivisions, where each successive value halves the previous one. The whole note, also known as the semibreve in British terminology, is depicted as an open oval notehead without a stem and typically lasts four beats in common time (4/4 meter).[21][22] The half note or minim features an open oval notehead attached to a vertical stem and endures for two beats, half the duration of a whole note.[21][23] The quarter note, or crotchet, has a filled (blackened) oval notehead with a stem and represents one beat, serving as the fundamental unit in many time signatures.[21][22] Shorter durations include the eighth note (quaver), which adds a single flag to the stem of a quarter note, lasting half a beat; the sixteenth note (semiquaver), with two flags and a quarter of a beat; and further subdivisions like the thirty-second note (demisemiquaver) with three flags.[21][20] In groups of multiple short notes, flags are often replaced by beams—horizontal lines connecting the stems—to enhance readability.[20] To extend or modify these basic durations, additional symbols are employed. A tie is a curved line connecting the heads of two or more adjacent notes of the same pitch, combining their values into a single sustained sound; for example, tying two quarter notes produces a duration equivalent to a half note.[23][21] A dot placed after a notehead augments its value by half, such as a dotted quarter note equaling one and a half beats (three eighth notes); double dots further add a quarter of the original value for more precise rhythmic complexity.[23][20] These duration symbols operate within a metrical context defined by time signatures, which indicate the number of beats per measure and the note value assigned to each beat. For instance, in 4/4 time, the upper numeral 4 specifies four beats per measure, while the lower 4 designates the quarter note as the beat unit; in 3/4, three quarter-note beats form a measure, common in waltzes.[24][21] This structure ensures rhythmic coherence, with durations aligning to the beat subdivision for synchronized performance across instruments.[20]| Note Name (American/British) | Appearance | Relative Duration (in 4/4 time) |

|---|---|---|

| Whole note / Semibreve | Open oval, no stem | 4 beats |

| Half note / Minim | Open oval with stem | 2 beats |

| Quarter note / Crotchet | Filled oval with stem | 1 beat |

| Eighth note / Quaver | Filled oval with stem and 1 flag (or beam) | 1/2 beat |

| Sixteenth note / Semiquaver | Filled oval with stem and 2 flags (or beam) | 1/4 beat |

Accidentals and chromatic alterations

In Western music notation, accidentals are symbols placed before a note to alter its pitch from the diatonic scale defined by the key signature. The sharp (♯) raises the pitch by one semitone, the flat (♭) lowers it by one semitone, and the natural (♮) cancels any previous sharp or flat, restoring the note to its original pitch as indicated by the key signature.[25][26] These symbols are positioned on the staff immediately before the note they affect, typically in the same octave, and their alteration applies to all subsequent notes of the same pitch class within the same measure (bar) unless overridden by another accidental or a natural sign.[25][27] For instance, a sharp applied to a G in one measure will cause all subsequent Gs in that measure to be played as G♯, but the effect ends at the bar line and does not carry over to the next measure without reapplication. Double accidentals extend these alterations: the double sharp (𝄪) raises a note by two semitones (a whole step), while the double flat (𝄫) lowers it by two semitones; each also cancels prior accidentals on that note.[25] These are used in contexts like harmonic analysis or modulations where maintaining traditional scale degrees is preferable to enharmonic equivalents, such as notating C𝄪 instead of D in C major to preserve its identity as the augmented fourth scale degree.[28] Beyond standard semitonal changes, contemporary music often employs extensions for finer chromatic alterations, including quarter-tone symbols that divide the semitone into halves. The Stein-Zimmermann system, a widely adopted standard, uses modified accidentals like the half sharp (raising by a quarter tone) and reversed flat (lowering by a quarter tone), along with arrow variants for even smaller intervals such as eighth tones; these are implemented in notation software like Sibelius and LilyPond.[29] Composers like Iannis Xenakis have utilized such notations, extending traditional symbols with arrows or minimal additions to indicate microtonal shifts in works like Nomos Alpha, enabling precise expression on instruments like strings or winds.[30] In non-Western traditions, similar microtonal concepts appear, such as the Indian shrutis, which represent 22 subtle pitch intervals subdividing the octave beyond the 12 semitones, often notated through variations in swara names like komal (flat) or shuddha (natural) with contextual adjustments for raga-specific intonations.[31][32] These allow for expressive nuances, as in the flatter reeshabh in Raga Ahir Bhairav, though formal Western-style symbols are rarely used, relying instead on oral tradition and approximate staff placements.[32]Pitch Structure and Scales

Diatonic scale degrees

In diatonic scales, pitches are organized into seven distinct degrees relative to a central tonic note, forming the foundational structure for many Western musical modes, such as the major and natural minor scales.[33] These degrees are numbered from 1 to 7, with the tonic as degree 1, and they cycle through the letter names A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, repeating in subsequent octaves to build scales. This seven-note framework distinguishes diatonic scales from chromatic ones by emphasizing whole and half steps between consecutive degrees, creating a hierarchical tonal organization that underpins harmony and melody.[34] The technical names for these scale degrees reflect their functional roles in music theory: degree 1 is the tonic, providing stability and resolution; degree 2 is the supertonic, often leading away from the tonic; degree 3 is the mediant, bridging tonic and dominant; degree 4 is the subdominant, introducing a sense of departure; degree 5 is the dominant, creating tension that resolves back to the tonic; degree 6 is the submediant, offering relative minor or major contrast; and degree 7 is the leading tone in major scales (tending strongly to resolve to the tonic) or the subtonic in natural minor scales (providing a softer resolution).[33] These names remain consistent across major and minor modes, though their intervallic relationships differ slightly.[34] In the major scale, the interval pattern between degrees follows whole-whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half steps (W-W-H-W-W-W-H), resulting in major seconds between degrees 1-2, 2-3, 4-5, 5-6, and 6-7, and minor seconds between 3-4 and 7-1.[33] For example, in C major, the degrees are C (1, tonic), D (2, supertonic), E (3, mediant), F (4, subdominant), G (5, dominant), A (6, submediant), and B (7, leading tone).[35] In contrast, the natural minor scale uses a whole-half-whole-whole-half-whole-whole pattern (W-H-W-W-H-W-W), featuring a minor third from degree 1 to 3, and treating degree 7 as the subtonic with a whole step to the tonic.[34] An example is A minor: A (1, tonic), B (2, supertonic), C (3, mediant), D (4, subdominant), E (5, dominant), F (6, submediant), and G (7, subtonic).[33]| Scale Degree | Technical Name | Interval to Next (Major) | Interval to Next (Natural Minor) | Example in C Major | Example in A Minor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tonic | Whole step | Whole step | C | A |

| 2 | Supertonic | Whole step | Half step | D | B |

| 3 | Mediant | Half step | Whole step | E | C |

| 4 | Subdominant | Whole step | Whole step | F | D |

| 5 | Dominant | Whole step | Half step | G | E |

| 6 | Submediant | Whole step | Whole step | A | F |

| 7 | Leading tone / Subtonic | Half step | Whole step | B | G |