Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Protocol stack

View on Wikipedia

The protocol stack or network stack is an implementation of a computer networking protocol suite or protocol family. Some of these terms are used interchangeably, but strictly speaking, the suite is the definition of the communication protocols, and the stack is the software implementation of them.[1]

Individual protocols within a suite are often designed with a single purpose in mind. This modularization simplifies design and evaluation. Because each protocol module usually communicates with two others, they are commonly imagined as layers in a stack of protocols. The lowest protocol always deals with low-level interaction with the communications hardware. Each higher layer adds additional capabilities. User applications usually deal only with the topmost layers.[2]

General protocol suite description

[edit]T ~ ~ ~ T [A] [B]_____[C]

Imagine three computers: A, B, and C. A and B both have radio equipment and can communicate via the airwaves using a suitable network protocol (such as IEEE 802.11). B and C are connected via a cable, using it to exchange data (again, with the help of a protocol, for example Point-to-Point Protocol). However, neither of these two protocols will be able to transport information from A to C, because these computers are conceptually on different networks. An inter-network protocol is required to connect them.

One could combine the two protocols to form a powerful third, mastering both cable and wireless transmission, but a different super-protocol would be needed for each possible combination of protocols. It is easier to leave the base protocols alone and design a protocol that can work on top of any of them (the Internet Protocol is an example). This will make two stacks of two protocols each. The inter-network protocol will communicate with each of the base protocols in their simpler language; the base protocols will not talk directly to each other.

A request on computer A to send a chunk of data to C is taken by the upper protocol, which (through whatever means) knows that C is reachable through B. It, therefore, instructs the wireless protocol to transmit the data packet to B. On this computer, the lower-layer handlers will pass the packet up to the inter-network protocol, which, on recognizing that B is not the final destination, will again invoke lower-level functions. This time, the cable protocol is used to send the data to C. There, the received packet is again passed to the upper protocol, which (with C being the destination) will pass it on to a higher protocol or application on C.

In practical implementation, protocol stacks are often divided into three major sections: media, transport, and applications. A particular operating system or platform will often have two well-defined software interfaces: one between the media and transport layers, and one between the transport layers and applications. The media-to-transport interface defines how transport protocol software makes use of particular media and hardware types and is associated with a device driver. For example, this interface level would define how TCP/IP transport software would talk to the network interface controller. Examples of these interfaces include ODI and NDIS in the Microsoft Windows and DOS environment. The application-to-transport interface defines how application programs make use of the transport layers. For example, this interface level would define how a web browser program would talk to TCP/IP transport software. Examples of these interfaces include Berkeley sockets and System V STREAMS in Unix-like environments, and Winsock for Microsoft Windows.

Examples

[edit]

| Protocol | Layer |

|---|---|

| HTTP | Application |

| TCP | Transport |

| IP | Internet or network |

| Ethernet | Link or data link |

| IEEE 802.3ab | Physical |

Spanning layer

[edit]An important feature of many communities of interoperability based on a common protocol stack is a spanning layer, a term coined by David Clark[3]

Certain protocols are designed with the specific purpose of bridging differences at the lower layers, so that common agreements are not required there. Instead, the layer provides the definitions that permit translation to occur between a range of services or technologies used below. Thus, in somewhat abstract terms, at and above such a layer common standards contribute to interoperation, while below the layer translation is used. Such a layer is called a spanning layer in this paper. As a practical matter, real interoperation is achieved by the definition and use of effective spanning layers. But there are many different ways that a spanning layer can be crafted.

In the Internet protocol stack, the Internet Protocol Suite constitutes a spanning layer that defines a best-effort service for global routing of datagrams at Layer 3. The Internet is the community of interoperation based on this spanning layer.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "What is a protocol stack?". WEBOPEDIA. 24 September 1997. Retrieved 2010-02-21.

A [protocol stack is a] set of network protocol layers that work together. The OSI Reference Model that defines seven protocol layers is often called a stack, as is the set of TCP/IP protocols that define communication over the Internet.

- ^ Georg N. Strauß (2010-01-09). "The OSI Model, Part 10. The Application Layer". Ika-Reutte. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2010-02-21.

The Application layer is the topmost layer of the OSI model, and it provides services that directly support user applications, such as database access, e-mail, and file transfers.

- ^ David Clark (1997). Interoperation, Open Interfaces, and Protocol Architecture. National Research Council. ISBN 9780309060363.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

Protocol stack

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Terminology

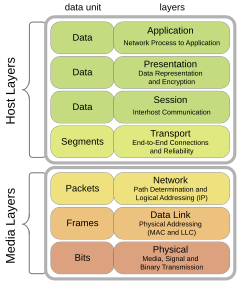

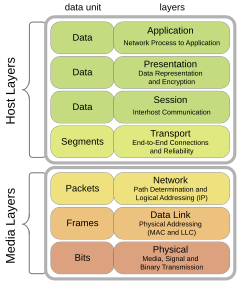

A protocol stack is a vertical sequence of protocols organized in layers, where each layer provides specific services to the layer above it while relying on the services of the layer below it to handle data transmission across networks. This layered organization enables modular communication by encapsulating data at each level, adding protocol-specific headers or footers as needed for processing and forwarding.[6][7] A protocol suite refers to a set of interrelated protocols organized across layers that work together to enable network communication, such as the TCP/IP suite. The term "protocol family" is sometimes used interchangeably for such cohesive sets of protocols.[8] In contrast, non-layered approaches, such as monolithic protocols, integrate all communication functions into a single, undifferentiated unit without distinct layers, which can complicate implementation and adaptation in diverse environments.[9] The modularity inherent in a protocol stack offers key benefits, including abstraction that hides lower-layer complexities from higher layers, interoperability across heterogeneous systems and devices, and ease of maintenance through isolated updates to individual layers. These advantages arise from the layered design's ability to standardize interfaces, allowing independent evolution of protocols without disrupting the overall system. Protocol stacks are commonly visualized as a series of horizontal bands stacked vertically, with each band representing a distinct layer—from physical transmission at the bottom to application-specific services at the top—illustrating the hierarchical flow of data encapsulation and decapsulation.[10][7]Historical Development

The concept of a protocol stack emerged from early efforts in packet-switched networking during the 1960s, with the ARPANET project serving as a foundational example. Initiated by the U.S. Department of Defense's Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), ARPANET's first successful packet transmission occurred on October 29, 1969, between UCLA and the Stanford Research Institute, marking the birth of practical internetworking protocols.[11] By 1970, the Network Control Protocol (NCP) was deployed on ARPANET as its initial host-to-host communication standard, handling data transfer and simple error control but lacking support for internetworking across diverse networks.[12] In the 1970s, layered protocol designs gained traction through parallel developments. The French CYCLADES project, led by Louis Pouzin starting in 1971, introduced a datagram-based architecture that emphasized end-to-end error correction and minimal network-layer intervention, influencing future stack designs by promoting modularity and simplicity.[13] Concurrently, Vinton Cerf and Robert Kahn outlined the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) in their seminal 1974 paper, "A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication," proposing a layered approach to interconnect heterogeneous packet networks while separating transport from internetworking functions—ideas that evolved into TCP/IP.[14] A pivotal milestone came on January 1, 1983, when ARPANET transitioned from NCP to TCP/IP, mandated by the Department of Defense as the standard for military networks; this "flag day" cutover enabled scalable internetworking and laid the groundwork for the modern Internet.[15] In 1984, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) published the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) Reference Model as ISO 7498, formalizing a seven-layer architecture to promote vendor-neutral interoperability, though it competed with the more pragmatic TCP/IP suite.[16] The 1990s saw rapid evolution through Internet commercialization, as the National Science Foundation lifted restrictions on commercial traffic in 1991 and privatized NSFNET in 1995, spurring widespread adoption of TCP/IP stacks in business and consumer applications.[11] Post-2000 developments extended protocol stacks to address emerging needs. IPv6, specified in RFC 2460 in 1998 to overcome IPv4 address exhaustion, saw widespread adoption in the 2010s, with global traffic reaching about 40% by 2023 and approximately 43% as of early 2025, driven by mobile and IoT growth.[17] Similarly, the IEEE 802.11 standard for wireless LANs, ratified in 1997, introduced layered protocols for radio-based networking, influencing hybrid stacks that integrate Wi-Fi with IP-based systems.[18] These advancements, building on DoD-mandated TCP/IP standards, solidified protocol stacks as the backbone of global connectivity.[12]Architectural Principles

Layered Architecture

The layered architecture organizes network protocols into hierarchical levels, each serving as an abstraction boundary that encapsulates specific functionalities while hiding implementation details from adjacent layers. This design principle divides the complex process of communication into manageable modules, with lower layers typically handling physical transmission and basic connectivity—such as bit-level signaling over media—while upper layers manage higher-level logic, including data formatting and application-specific processing. Protocol stacks commonly employ 4 to 7 layers, depending on the architectural model, to balance granularity and simplicity in decomposing network tasks.[19][20] Central to this architecture is the encapsulation process, where data traverses the stack vertically. As data descends from higher to lower layers, each layer adds its own header (and sometimes trailer) to the Protocol Data Unit (PDU) from the layer above, forming a composite packet that includes control information tailored to that layer's responsibilities. For instance, a generic packet might consist of an application-layer payload encapsulated within a transport-layer segment (with sequencing details), which is then wrapped in a network-layer datagram (adding routing metadata), and finally embedded in a data-link frame (including addressing for local delivery), before reaching the physical layer for transmission as bits. Upon ascent at the receiving end, layers reverse this process by stripping headers in sequence, passing the refined PDU upward until the original data is reconstructed at the application layer. This mechanism ensures modular processing without requiring layers to understand distant operations.[21][20] The benefits of layered architecture include enhanced fault isolation, where malfunctions or modifications in one layer are contained without propagating to others, facilitating debugging and upgrades in large-scale systems. Standardization at layer interfaces promotes interoperability across diverse hardware and vendors, accelerating protocol adoption and innovation. However, challenges arise from the cumulative overhead of multiple headers, which can increase packet size and processing latency—potentially reducing efficiency in bandwidth-constrained environments—and may impose rigidity that complicates cross-layer optimizations.[19][21][22] In modern fault-tolerant designs, layer independence has proven particularly valuable in cloud networking, where paradigms like Software-Defined Networking (SDN) explicitly separate control and data planes to enable resilient, programmable infrastructures. By decoupling decision-making from forwarding operations through open interfaces, SDN allows independent scaling and recovery mechanisms, such as distributed controllers for failover, thereby mitigating single points of failure in dynamic cloud environments post-2010.[23]Protocol Interactions

In protocol stacks, interactions occur along two primary dimensions: horizontal communication between peer entities at the same layer across different systems, and vertical communication between adjacent layers within a single system. Horizontal interactions enable protocols at equivalent layers to exchange information for coordination and data transfer, while vertical interactions allow upper layers to request services from lower layers, forming the operational basis of the layered architecture. This dual communication model ensures modular cooperation, where each layer abstracts complexity for the one above it without direct peer involvement from higher levels.[24][25] Intra-layer interactions involve peer protocols at the same layer communicating by exchanging protocol data units (PDUs), which are structured messages containing headers for control and payloads for data. These exchanges occur through service access points (SAPs), logical interfaces that define entry points for protocol invocation and data handover between peers. As PDUs traverse downward through the stack during encapsulation, they evolve in form and nomenclature—for instance, from segments at higher layers to packets and then frames at lower layers—to accommodate layer-specific formatting, addressing, and error detection needs. This peer-to-peer exchange ensures consistent handling of data across distributed systems without exposing underlying implementation details.[26][27][28][29] Inter-layer services facilitate vertical communication through standardized primitives that invoke operations between layers: a request primitive from an upper layer to a lower one initiates a service, an indication primitive notifies the upper layer of events from below, a response primitive allows the upper layer to reply to an indication, and a confirm primitive delivers completion status back to the requesting layer. These primitives support two main service models—connection-oriented, which establishes a virtual circuit with setup, data transfer, and teardown phases for reliable sequencing, and connectionless, which sends datagrams independently without prior setup for efficiency in low-overhead scenarios. At the transport layer, basic error handling mechanisms such as acknowledgments confirm receipt of PDUs and trigger retransmissions for lost or corrupted ones, enhancing overall reliability without delving into application-specific details.[30][31][32][33][34] In software implementations, protocol interactions are exposed through application programming interfaces (APIs), such as the Berkeley sockets API introduced in Unix systems during the 1980s, which abstracts layer communications into functions for creating endpoints, binding addresses, and managing data flows. This API enables applications to interact with the protocol stack transparently, handling both horizontal peer exchanges and vertical service invocations without requiring direct manipulation of PDUs or primitives. Post-1980s developments in Unix-like systems standardized these interfaces, promoting portability and ease of integration for networked applications.[35][36]Standard Protocol Suites

OSI Model

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) reference model is a conceptual framework that divides the functions of a networking system into seven distinct abstraction layers to facilitate interoperability between diverse systems. Developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) through its Joint Technical Committee 1 (JTC 1), the model was first published in 1984 as ISO/IEC 7498, with the edition canceling and replacing the initial 1984 version formalized in 1994 as ISO/IEC 7498-1.[37] This structure provides a common basis for coordinating the development of standards for systems interconnection, allowing existing standards to be placed in perspective while identifying areas for improvement, without serving as an implementation specification.[37] The model emerged from ISO's efforts starting in 1977 to create general networking standards, culminating in a layered architecture that separates concerns for clarity and modularity in communication protocols.[38] The OSI model's seven layers, from bottom to top, are the Physical, Data Link, Network, Transport, Session, Presentation, and Application layers, each with specific functions to handle aspects of data communication. The Physical layer (Layer 1) transmits raw bit streams over physical media, defining electrical, mechanical, and functional specifications for devices like cables and connectors; examples include Ethernet physical signaling and RS-232 standards.[39] The Data Link layer (Layer 2) provides node-to-node data transfer, including framing, error detection, and flow control; protocols such as Ethernet (MAC sublayer) and Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP) operate here.[39] The Network layer (Layer 3) handles routing, logical addressing, and packet forwarding across interconnected networks; Internet Protocol (IP) and Connectionless Network Protocol (CLNP) are representative.[39] The Transport layer (Layer 4) ensures end-to-end delivery, reliability, and multiplexing; Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP) exemplify this.[39] The Session layer (Layer 5) manages communication sessions, including establishment, synchronization, and termination; examples include NetBIOS and RPC (Remote Procedure Call).[39] The Presentation layer (Layer 6) translates data formats, handles encryption, and compression; protocols like Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)/Transport Layer Security (TLS) and Abstract Syntax Notation One (ASN.1) fit here.[39] Finally, the Application layer (Layer 7) interfaces directly with end-user applications, providing network services such as file transfer and email; Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and File Transfer Protocol (FTP) are key examples.[39]| Layer | Name | Primary Function | Example Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Application | Provides network services to applications | HTTP, FTP |

| 6 | Presentation | Translates data representations and ensures syntax | TLS, ASN.1 |

| 5 | Session | Manages dialogues and sessions between applications | NetBIOS, RPC |

| 4 | Transport | Delivers reliable end-to-end data transfer | TCP, UDP |

| 3 | Network | Routes packets across networks | IP, CLNP |

| 2 | Data Link | Transfers frames reliably between adjacent nodes | Ethernet, PPP |

| 1 | Physical | Transmits bits over physical medium | Ethernet PHY, RS-232 |

TCP/IP Suite

The TCP/IP protocol suite, also known as the Internet protocol suite, serves as the foundational architecture for data communication across the global Internet, providing a practical framework for interconnecting diverse networks. Developed through collaborative efforts by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and academic researchers in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it emphasizes simplicity, robustness, and interoperability over rigid theoretical layering. Unlike more abstract models, the TCP/IP suite prioritizes implementable protocols that enable reliable and efficient packet-switched networking, forming the backbone of modern digital infrastructure. The suite is typically organized into four layers: the link layer (also called network access or network interface), which handles hardware-specific transmission over physical media; the internet layer, responsible for logical addressing and routing; the transport layer, which manages end-to-end data delivery; and the application layer, where user-facing services operate. Some descriptions expand this to five layers by separating the physical layer (raw bit transmission) from the link layer, reflecting variations in implementation. This structure originated from the DoD's reference model formalized around 1983, which guided the development of interoperable protocols for ARPANET successors. The design draws conceptual influence from the OSI model in promoting modular layering but adapts it for real-world deployment with fewer, more flexible divisions. At the internet layer, the Internet Protocol (IP) provides connectionless packet routing and addressing, as specified in its version 4 (IPv4) standard published in 1981. The transport layer features two primary protocols: the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), which ensures reliable, ordered delivery through mechanisms like the three-way handshake for connection establishment, congestion control, and error recovery; and the User Datagram Protocol (UDP), a lightweight, connectionless alternative suitable for time-sensitive applications without reliability guarantees. The application layer supports protocols such as the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) for web communication and the Domain Name System (DNS) for address resolution, enabling diverse services atop the lower layers. The suite evolved to address scalability and security challenges. IPv4's 32-bit addressing, while revolutionary, faced exhaustion due to Internet growth, prompting the development of IPv6 with 128-bit addresses in 1998 to support vastly expanded connectivity. Security enhancements include IPsec, introduced in 1995 to provide authentication, integrity, and encryption at the internet layer through protocols like Authentication Header (AH) and Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP). For transport-layer security, the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol, first standardized in 1999, secures application data in transit, with its latest version (1.3) in 2018 improving performance by reducing handshake rounds and mandating forward secrecy. Implementation of the TCP/IP suite is deeply integrated into operating systems via APIs like Berkeley sockets, first introduced in 4.2BSD Unix in 1983, which abstract network operations for developers using functions such assocket(), bind(), and connect(). This interface standardized TCP/IP programming across platforms, facilitating widespread adoption. As of 2025, the suite underpins nearly all Internet traffic, with reports indicating that TCP and UDP together account for over 95% of global data flows, powering everything from web browsing to streaming services.