Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Northern blot

View on Wikipedia

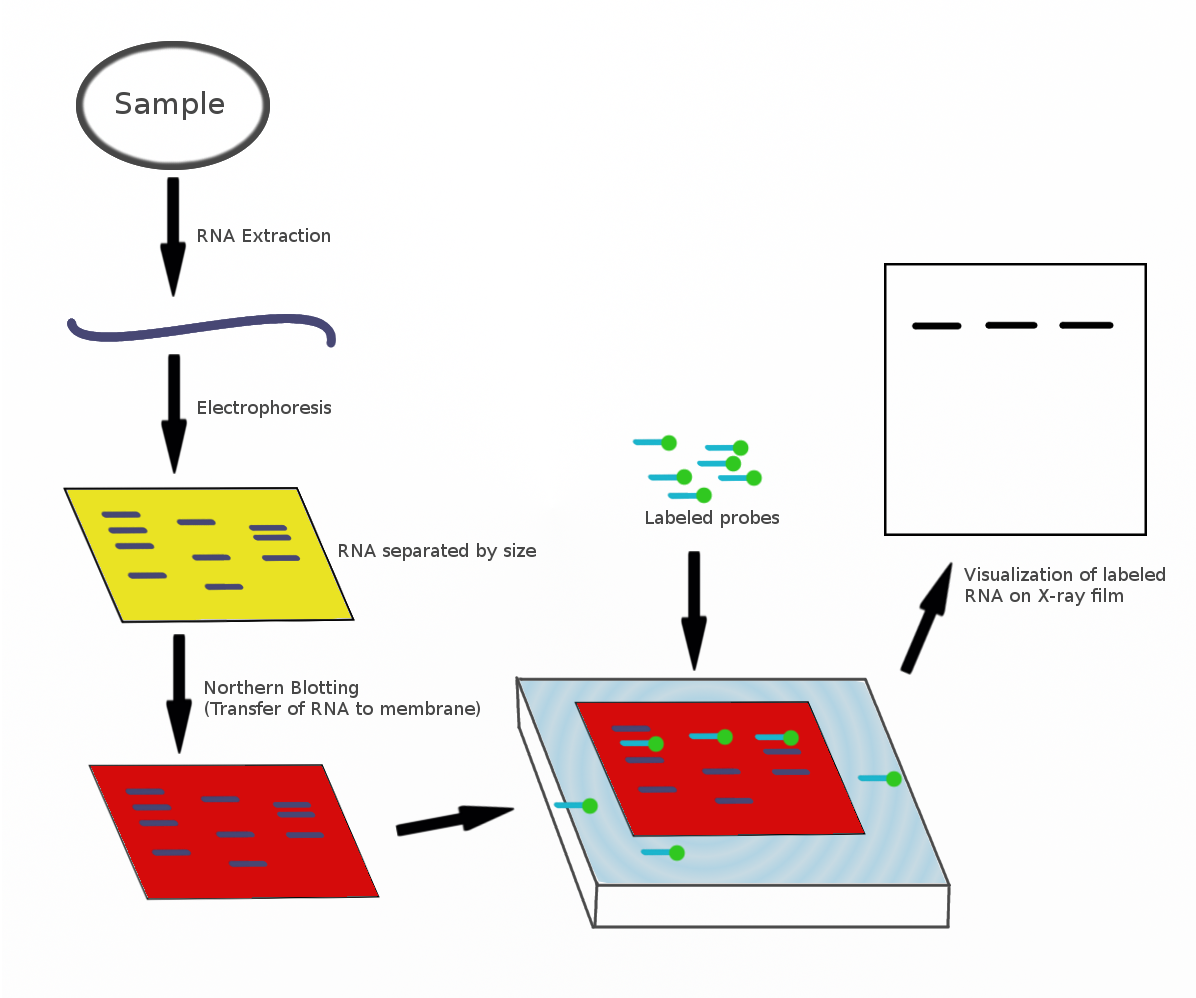

The northern blot, or RNA blot,[1] is a technique used in molecular biology research to study gene expression by detection of RNA (or isolated mRNA) in a sample.[2][3]

With northern blotting it is possible to observe cellular control over structure and function by determining the particular gene expression rates during differentiation and morphogenesis, as well as in abnormal or diseased conditions.[4] Northern blotting involves the use of electrophoresis to separate RNA samples by size, and detection with a hybridization probe complementary to part of or the entire target sequence. Strictly speaking, the term 'northern blot' refers specifically to the capillary transfer of RNA from the electrophoresis gel to the blotting membrane. However, the entire process is commonly referred to as northern blotting.[5] The northern blot technique was developed in 1977 by James Alwine, David Kemp, and George Stark at Stanford University.[6] Northern blotting takes its name from its similarity to the first blotting technique, the Southern blot, named for biologist Edwin Southern.[2] The major difference is that RNA, rather than DNA, is analyzed in the northern blot.[7]

Procedure

[edit]A general blotting procedure[5] starts with extraction of total RNA from a homogenized tissue sample or from cells. Eukaryotic mRNA can then be isolated through the use of oligo (dT) cellulose chromatography to isolate only those RNAs with a poly(A) tail.[8][9] RNA samples are then separated by gel electrophoresis. Since the gels are fragile and the probes are unable to enter the matrix, the RNA samples, now separated by size, are transferred to a nylon membrane through a capillary or vacuum blotting system.

A nylon membrane with a positive charge is the most effective for use in northern blotting since the negatively charged nucleic acids have a high affinity for them. The transfer buffer used for the blotting usually contains formamide because it lowers the annealing temperature of the probe-RNA interaction, thus eliminating the need for high temperatures, which could cause RNA degradation.[10] Once the RNA has been transferred to the membrane, it is immobilized through covalent linkage to the membrane by UV light or heat. After a probe has been labeled, it is hybridized to the RNA on the membrane. Experimental conditions that can affect the efficiency and specificity of hybridization include ionic strength, viscosity, duplex length, mismatched base pairs, and base composition.[11] The membrane is washed to ensure that the probe has bound specifically and to prevent background signals from arising. The hybrid signals are then detected by X-ray film and can be quantified by densitometry. To create controls for comparison in a northern blot, samples not displaying the gene product of interest can be used after determination by microarrays or RT-PCR.[11]

Gels

[edit]

The RNA samples are most commonly separated on agarose gels containing formaldehyde as a denaturing agent for the RNA to limit secondary structure.[11][12] The gels can be stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr) and viewed under UV light to observe the quality and quantity of RNA before blotting.[11] Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with urea can also be used in RNA separation but it is most commonly used for fragmented RNA or microRNAs.[13] An RNA ladder is often run alongside the samples on an electrophoresis gel to observe the size of fragments obtained but in total RNA samples the ribosomal subunits can act as size markers.[11] Since the large ribosomal subunit is 28S (approximately 5kb) and the small ribosomal subunit is 18S (approximately 2kb) two prominent bands appear on the gel, the larger at close to twice the intensity of the smaller.[11][14]

Probes

[edit]Probes for northern blotting are composed of nucleic acids with a complementary sequence to all or part of the RNA of interest. They can be DNA, RNA, or oligonucleotides with a minimum of 25 complementary bases to the target sequence.[5] RNA probes (riboprobes) that are transcribed in vitro are able to withstand more rigorous washing steps preventing some of the background noise.[11] Commonly cDNA is created with labelled primers for the RNA sequence of interest to act as the probe in the northern blot.[15] The probes must be labelled either with radioactive isotopes (32P) or with chemiluminescence in which alkaline phosphatase or horseradish peroxidase (HRP) break down chemiluminescent substrates producing a detectable emission of light.[16] The chemiluminescent labelling can occur in two ways: either the probe is attached to the enzyme, or the probe is labelled with a ligand (e.g. biotin) for which the ligand (e.g., avidin or streptavidin) is attached to the enzyme (e.g. HRP).[11] X-ray film can detect both the radioactive and chemiluminescent signals and many researchers prefer the chemiluminescent signals because they are faster, more sensitive, and reduce the health hazards that go along with radioactive labels.[16] The same membrane can be probed up to five times without a significant loss of the target RNA.[10]

Applications

[edit]Northern blotting allows one to observe a particular gene's expression pattern between tissues, organs, developmental stages, environmental stress levels, pathogen infection, and over the course of treatment.[9][15][17] The technique has been used to show overexpression of oncogenes and downregulation of tumor-suppressor genes in cancerous cells when compared to 'normal' tissue,[11] as well as the gene expression in the rejection of transplanted organs.[18] If an upregulated gene is observed by an abundance of mRNA on the northern blot the sample can then be sequenced to determine if the gene is known to researchers or if it is a novel finding.[18] The expression patterns obtained under given conditions can provide insight into the function of that gene. Since the RNA is first separated by size, if only one probe type is used variance in the level of each band on the membrane can provide insight into the size of the product, suggesting alternative splice products of the same gene or repetitive sequence motifs.[8][14] The variance in size of a gene product can also indicate deletions or errors in transcript processing. By altering the probe target used along the known sequence it is possible to determine which region of the RNA is missing.[2]

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]Analysis of gene expression can be done by several different methods including RT-PCR, RNase protection assays, microarrays, RNA-Seq, serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE), as well as northern blotting.[4][5] Microarrays are quite commonly used and are usually consistent with data obtained from northern blots; however, at times northern blotting is able to detect small changes in gene expression that microarrays cannot.[19] The advantage that microarrays have over northern blots is that thousands of genes can be visualized at a time, while northern blotting is usually looking at one or a small number of genes.[17][19]

A problem in northern blotting is often sample degradation by RNases (both endogenous to the sample and through environmental contamination), which can be avoided by proper sterilization of glassware and the use of RNase inhibitors such as DEPC (diethylpyrocarbonate).[5] The chemicals used in most northern blots can be a risk to the researcher, since formaldehyde, radioactive material, ethidium bromide, DEPC, and UV light are all harmful under certain exposures.[11] Compared to RT-PCR, northern blotting has a low sensitivity, but it also has a high specificity, which is important to reduce false positive results.[11]

The advantages of using northern blotting include the detection of RNA size, the observation of alternate splice products, the use of probes with partial homology, the quality and quantity of RNA can be measured on the gel prior to blotting, and the membranes can be stored and reprobed for years after blotting.[11]

For northern blotting for the detection of acetylcholinesterase mRNA the nonradioactive technique was compared to a radioactive technique and found as sensitive as the radioactive one, but requires no protection against radiation and is less time-consuming.[20]

Reverse northern blot

[edit]Researchers occasionally use a variant of the procedure known as the reverse northern blot. In this procedure, the substrate nucleic acid (that is affixed to the membrane) is a collection of isolated DNA fragments, and the probe is RNA extracted from a tissue and radioactively labelled. The use of DNA microarrays that have come into widespread use in the late 1990s and early 2000s is more akin to the reverse procedure, in that they involve the use of isolated DNA fragments affixed to a substrate, and hybridization with a probe made from cellular RNA. Thus the reverse procedure, though originally uncommon, enabled northern analysis to evolve into gene expression profiling, in which many (possibly all) of the genes in an organism may have their expression monitored.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gilbert, S. F. (2000) Developmental Biology, 6th Ed. Sunderland MA, Sinauer Associates.

- ^ a b c Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J. Raff, M., Roberts, K., Walter, P. 2008. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 5th ed. Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group, NY, pp 538–539.

- ^ Kevil, C. G., Walsh, L., Laroux, F. S., Kalogeris, T., Grisham, M. B., Alexander, J. S. (1997) An Improved, Rapid Northern Protocol. Biochem. and Biophys. Research Comm. 238:277–279.

- ^ a b Schlamp, K.; Weinmann, A.; Krupp, M.; Maass, T.; Galle, P. R.; Teufel, A. (2008). "BlotBase: A northern blot database". Gene. 427 (1–2): 47–50. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2008.08.026. PMID 18838116.

- ^ a b c d e Trayhurn, P. (1996) Northern Blotting. Pro. Nutrition Soc. 55:583–589.

- ^ Alwine JC, Kemp DJ, Stark GR (1977). "Method for detection of specific RNAs in agarose gels by transfer to diazobenzyloxymethyl-paper and hybridization with DNA probes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (12): 5350–4. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5350A. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5350. PMC 431715. PMID 414220.

- ^ Bor, Y.C.; Swartz, J.; Li, Y.; Coyle, J.; Rekosh, D.; Hammarskjold, Marie-Louise (2006). "Northern Blot analysis of mRNA from mammalian polyribosomes". Nature Protocols. doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.216.

- ^ a b Durand, G. M.; Zukin, R. S. (1993). "Developmental Regulation of mRNAs Encoding Rat Brain Kainate/AMPA Receptors: A Northern Analysis Study". J. Neurochem. 61 (6): 2239–2246. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07465.x. PMID 8245974. S2CID 33955961.

- ^ a b Mori, H.; Takeda-Yoshikawa, Y.; Hara-Nishimura, I.; Nishimura, M. (1991). "Pumpkin malate synthase Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA and Northern blot analysis". Eur. J. Biochem. 197 (2): 331–336. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15915.x. PMID 1709098.

- ^ a b Yang, H.; McLeese, J.; Weisbart, M.; Dionne, J.-L.; Lemaire, I.; Aubin, R. A. (1993). "Simplified high throughput protocol for Northern hybridization". Nucleic Acids Research. 21 (14): 3337–3338. doi:10.1093/nar/21.14.3337. PMC 309787. PMID 8341618.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Streit, S.; Michalski, C. W.; Erkan, M.; Kleef, J.; Friess, H. (2009). "Northern blot analysis for detection of RNA in pancreatic cancer cells and tissues". Nature Protocols. 4 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1038/nprot.2008.216. PMID 19131955. S2CID 24980302.

- ^ Yamanaka, S.; Poksay, K. S.; Arnold, K. S.; Innerarity, T. L. (1997). "A novel translational repressor mRNA is edited extensively in livers containing tumors caused by the transgene expression of the apoB mRNA-editing enzyme". Genes Dev. 11 (3): 321–333. doi:10.1101/gad.11.3.321. PMID 9030685.

- ^ Valoczi, A., Hornyik, C., Varga, N., Burgyan, J., Kauppinen, S., Havelda, Z. (2004) Sensitive and specific detection of microRNAs by northern blot analysis using LNA-modified oligonucleotide probes. Nuc. Acids Research. 32: e175.

- ^ a b Gortner, G.; Pfenninger, M.; Kahl, G.; Weising, K. (1996). "Northern blot analysis of simple repetitive sequence transcription in plants". Electrophoresis. 17 (7): 1183–1189. doi:10.1002/elps.1150170702. PMID 8855401. S2CID 36857667.

- ^ a b Liang, P. Pardee, A. B. (1995) Recent advances in differential display. Current Opinion Immunol. 7: 274–280.

- ^ a b Engler-Blum, G.; Meier, M.; Frank, J.; Muller, G. A. (1993). "Reduction of Background Problems in Nonradioactive Northern and Southern Blot Analysis Enables Higher Sensitivity Than 32P-Based Hybridizations". Anal. Biochem. 210 (2): 235–244. doi:10.1006/abio.1993.1189. PMID 7685563.

- ^ a b Baldwin, D., Crane, V., Rice, D. (1999) A comparison of gel-based, nylon filter and microarray techniques to detect differential RNA expression in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biol. 2: 96–103.

- ^ a b Utans, U.; Liang, P.; Wyner, L. R.; Karnovsky, M. J.; Russel, M. E. (1994). "Chronic cardiac rejection: Identification of five upregulated genes in transplanted hearts by differential mRNA display". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91 (14): 6463–6467. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.6463U. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.14.6463. PMC 44222. PMID 8022806.

- ^ a b Taniguchi, M.; Miura, K.; Iwao, H.; Yamanaka, S. (2001). "Quantitative Assessment of DNA Microarrays – Comparison with Northern Blot Analysis". Genomics. 71 (1): 34–39. doi:10.1006/geno.2000.6427. PMID 11161795.

- ^ Kreft, K., Kreft, S., Komel, R., Grubič, Z. (2000). Nonradioactive northern blotting for the determination of acetylcholinesterase mRNA. Pflügers Arch – Eur J Physiol, 439:R66-R67