Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anode

View on Wikipedia

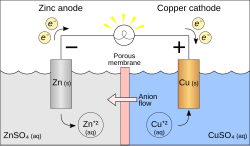

An anode usually is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, which is usually an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the device. A common mnemonic is ACID, for "anode current into device".[1] The direction of conventional current (the flow of positive charges) in a circuit is opposite to the direction of electron flow, so (negatively charged) electrons flow from the anode of a galvanic cell, into an outside or external circuit connected to the cell. For example, the end of a household battery marked with a "+" is the cathode (while discharging).

In both a galvanic cell and an electrolytic cell, the anode is the electrode at which the oxidation reaction occurs. In a galvanic cell the anode is the wire or plate having excess negative charge as a result of the oxidation reaction. In an electrolytic cell, the anode is the wire or plate upon which excess positive charge is imposed.[2] As a result of this, anions will tend to move towards the anode where they will undergo oxidation.

Historically, the anode of a galvanic cell was also known as the zincode because it was usually composed of zinc.[3][4]: pg. 209, 214

Charge flow

[edit]The terms anode and cathode are not defined by the voltage polarity of electrodes, but are usually defined by the direction of current through the electrode. An anode usually is the electrode of a device through which conventional current (positive charge) flows into the device from an external circuit, while a cathode usually is the electrode through which conventional current flows out of the device.

In general, if the current through the electrodes reverses direction, as occurs for example in a rechargeable battery when it is being charged, the roles of the electrodes as anode and cathode are reversed.[5] However, the definition of anode and cathode is different for electrical devices such as diodes and vacuum tubes where the electrode naming is fixed and does not depend on the actual charge flow (current). These devices usually allow substantial current flow in one direction but negligible current in the other direction. Therefore, the electrodes are named based on the direction of this "forward" current. In a diode the anode is the terminal through which current enters and the cathode is the terminal through which current leaves, when the diode is forward biased. The names of the electrodes do not change in cases where reverse current flows through the device. Similarly, in a vacuum tube only one electrode can thermionically emit electrons into the evacuated tube, so electrons can only enter the device from the external circuit through the heated electrode. Therefore, this electrode is permanently named the cathode, and the electrode through which the electrons exit the tube is named the anode.[5]

Conventional current depends not only on the direction the charge carriers move, but also the carriers' electric charge. The currents outside the device are usually carried by electrons in a metal conductor. Since electrons have a negative charge, the direction of electron flow is opposite to the direction of conventional current. Consequently, electrons leave the device through the anode and enter the device through the cathode.[5]

Examples

[edit]

The polarity of voltage on an anode with respect to an associated cathode varies depending on the device type and on its operating mode. In the following examples, the anode is negative in a device that provides power, and positive in a device that consumes power:

In a discharging battery or galvanic cell (diagram on left), the anode is the negative terminal: it is where conventional current flows into the cell. This inward current is carried externally by electrons moving outwards.[citation needed]

In a recharging battery, or an electrolytic cell, the anode is the positive terminal imposed by an external source of potential difference. The current through a recharging battery is opposite to the direction of current during discharge; in other words, the electrode which was the cathode during battery discharge becomes the anode while the battery is recharging.[citation needed]

In battery engineering, it is common to designate one electrode of a rechargeable battery the anode and the other the cathode according to the roles the electrodes play when the battery is discharged. This is despite the fact that the roles are reversed when the battery is charged. When this is done, "anode" simply designates the negative terminal of the battery and "cathode" designates the positive terminal.

In a diode, the anode is the terminal represented by the tail of the arrow symbol (flat side of the triangle), where conventional current flows into the device. Note the electrode naming for diodes is always based on the direction of the forward current (that of the arrow, in which the current flows "most easily"), even for types such as Zener diodes where the current of interest is the reverse current.

In vacuum tubes or gas-filled tubes, the anode is the terminal where current enters the tube.[6]

Etymology

[edit]The word was coined in 1834 from the Greek ἄνοδος (anodos), 'ascent', by William Whewell, who had been consulted[4] by Michael Faraday over some new names needed to complete a paper on the recently discovered process of electrolysis. In that paper Faraday explained that when an electrolytic cell is oriented so that electric current traverses the "decomposing body" (electrolyte) in a direction "from East to West, or, which will strengthen this help to the memory, that in which the sun appears to move", the anode is where the current enters the electrolyte, on the East side: "ano upwards, odos a way; the way which the sun rises".[7][8]

The use of 'East' to mean the 'in' direction (actually 'in' → 'East' → 'sunrise' → 'up') may appear contrived. Previously, as related in the first reference cited above, Faraday had used the more straightforward term "eisode" (the doorway where the current enters). His motivation for changing it to something meaning 'the East electrode' (other candidates had been "eastode", "oriode" and "anatolode") was to make it immune to a possible later change in the direction convention for current, whose exact nature was not known at the time. The reference he used to this effect was the Earth's magnetic field direction, which at that time was believed to be invariant. He fundamentally defined his arbitrary orientation for the cell as being that in which the internal current would run parallel to and in the same direction as a hypothetical magnetizing current loop around the local line of latitude which would induce a magnetic dipole field oriented like the Earth's. This made the internal current East to West as previously mentioned, but in the event of a later convention change it would have become West to East, so that the East electrode would not have been the 'way in' any more. Therefore, "eisode" would have become inappropriate, whereas "anode" meaning 'East electrode' would have remained correct with respect to the unchanged direction of the actual phenomenon underlying the current, then unknown but, he thought, unambiguously defined by the magnetic reference. In retrospect the name change was unfortunate, not only because the Greek roots alone do not reveal the anode's function any more, but more importantly because as we now know, the Earth's magnetic field direction on which the "anode" term is based is subject to reversals whereas the current direction convention on which the "eisode" term was based has no reason to change in the future.[citation needed]

Since the later discovery of the electron, an easier to remember and more durably correct technically although historically false, etymology has been suggested: anode, from the Greek anodos, 'way up', 'the way (up) out of the cell (or other device) for electrons'.[citation needed]

Electrolytic anode

[edit]In electrochemistry, the anode is where oxidation occurs and is the positive polarity contact in an electrolytic cell.[9] At the anode, anions (negative ions) are forced by the electrical potential to react chemically and give off electrons (oxidation) which then flow up and into the driving circuit. Mnemonics: LEO Red Cat (Loss of Electrons is Oxidation, Reduction occurs at the Cathode), or AnOx Red Cat (Anode Oxidation, Reduction Cathode), or OIL RIG (Oxidation is Loss, Reduction is Gain of electrons), or Roman Catholic and Orthodox (Reduction – Cathode, anode – Oxidation), or LEO the lion says GER (Losing electrons is Oxidation, Gaining electrons is Reduction).

This process is widely used in metals refining. For example, in copper refining, copper anodes, an intermediate product from the furnaces, are electrolysed in an appropriate solution (such as sulfuric acid) to yield high purity (99.99%) cathodes. Copper cathodes produced using this method are also described as electrolytic copper.

Historically, when non-reactive anodes were desired for electrolysis, graphite (called plumbago in Faraday's time) or platinum were chosen.[10] They were found to be some of the least reactive materials for anodes. Platinum erodes very slowly compared to other materials, and graphite crumbles and can produce carbon dioxide in aqueous solutions but otherwise does not participate in the reaction.[citation needed]

Battery or galvanic cell anode

[edit]

In a battery or galvanic cell, the anode is the negative electrode from which electrons flow out towards the external part of the circuit. Internally the positively charged cations are flowing away from the anode (even though it is negative and therefore would be expected to attract them, this is due to electrode potential relative to the electrolyte solution being different for the anode and cathode metal/electrolyte systems); but, external to the cell in the circuit, electrons are being pushed out through the negative contact and thus through the circuit by the voltage potential as would be expected.

Battery manufacturers may regard the negative electrode as the anode,[11] particularly in their technical literature. Though from an electrochemical viewpoint incorrect, it does resolve the problem of which electrode is the anode in a secondary (or rechargeable) cell. Using the traditional definition, the anode switches ends between charge and discharge cycles.[12]

Vacuum tube anode

[edit]

In electronic vacuum devices such as a cathode ray tube, the anode is the positively charged electron collector. In a tube, the anode is a charged positive plate that collects the electrons emitted by the cathode through electric attraction. It also accelerates the flow of these electrons.[citation needed]

Diode anode

[edit]In a semiconductor diode, the anode is the P-doped layer which initially supplies holes to the junction. In the junction region, the holes supplied by the anode combine with electrons supplied from the N-doped region, creating a depleted zone. As the P-doped layer supplies holes to the depleted region, negative dopant ions are left behind in the P-doped layer ('P' for positive charge-carrier ions). This creates a base negative charge on the anode. When a positive voltage is applied to anode of the diode from the circuit, more holes are able to be transferred to the depleted region, and this causes the diode to become conductive, allowing current to flow through the circuit. The terms anode and cathode should not be applied to a Zener diode, since it allows flow in either direction, depending on the polarity of the applied potential (i.e. voltage).[citation needed]

Sacrificial anode

[edit]

In cathodic protection, a metal anode that is more reactive to the corrosive environment than the metal system to be protected is electrically linked to the protected system. As a result, the metal anode partially corrodes or dissolves instead of the metal system. As an example, an iron or steel ship's hull may be protected by a zinc sacrificial anode, which will dissolve into the seawater and prevent the hull from being corroded. Sacrificial anodes are particularly needed for systems where a static charge is generated by the action of flowing liquids, such as pipelines and watercraft. Sacrificial anodes are also generally used in tank-type water heaters.

In 1824 to reduce the impact of this destructive electrolytic action on ships hulls, their fastenings and underwater equipment, the scientist-engineer Humphry Davy developed the first and still most widely used marine electrolysis protection system. Davy installed sacrificial anodes made from a more electrically reactive (less noble) metal attached to the vessel hull and electrically connected to form a cathodic protection circuit.

A less obvious example of this type of protection is the process of galvanising iron. This process coats iron structures (such as fencing) with a coating of zinc metal. As long as the zinc remains intact, the iron is protected from the effects of corrosion. Inevitably, the zinc coating becomes breached, either by cracking or physical damage. Once this occurs, corrosive elements act as an electrolyte and the zinc/iron combination as electrodes. The resultant current ensures that the zinc coating is sacrificed but that the base iron does not corrode. Such a coating can protect an iron structure for a few decades, but once the protecting coating is consumed, the iron rapidly corrodes.[13]

If, conversely, tin is used to coat steel, when a breach of the coating occurs it actually accelerates oxidation of the iron.[14]

Impressed current anode

[edit]Another cathodic protection is used on the impressed current anode.[15] It is made from titanium and covered with mixed metal oxide. Unlike the sacrificial anode rod, the impressed current anode does not sacrifice its structure. This technology uses an external current provided by a DC source to create the cathodic protection.[16] Impressed current anodes are used in larger structures like pipelines, boats, city water tower, water heaters and more.[17]

Related antonym

[edit]The opposite of an anode is a cathode. When the current through the device is reversed, the electrodes switch functions, so the anode becomes the cathode and the cathode becomes anode, as long as the reversed current is applied. The exception is diodes where electrode naming is always based on the forward current direction.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Anodizing

- Galvanic anode

- Gas-filled tube

- Primary cell

- Redox (reduction–oxidation)

References

[edit]- ^ Denker, John (2004). "How to Define Anode and Cathode". av8n.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2006.

- ^ Pauling, Linus; Pauling, Peter (1975). Chemistry. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0716701767. OCLC 1307272.

- ^ "Zincode definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Ross, S (1961). "Faraday Consults the Scholars: The Origins of the Terms of Electrochemistry". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 16 (2): 187–220. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1961.0038. S2CID 145600326.

- ^ a b c "Inside a Tube". Penta Labs. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ "Vacuum Tube Electrodes: Thermionc Valve Electrodes » Electronics Notes". www.electronics-notes.com. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ Faraday, Michael (January 1834). "Experimental Researches in Electricity. Seventh Series". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 124 (1): 77. Bibcode:1834RSPT..124...77F. doi:10.1098/rstl.1834.0008. S2CID 116224057. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. in which Faraday introduces the words electrode, anode, cathode, anion, cation, electrolyte, electrolyze

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1849). Experimental Researches in Electricity. Vol. 1. Taylor. hdl:2027/uc1.b4484853. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Reprint

- ^ McNaught, A. D.; Wilkinson, A. (1997). IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00370. ISBN 978-0-9678550-9-7.

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1849). Experimental Researches in Electricity. Vol. 1. London: University of London.

- ^ "What is the anode, cathode and electrolyte?". Duracell Frequently Asked Questions page. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Anode vs Cathode: What's the difference?". BioLogic. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Kamde, Deepak K.; Manickam, Karthikeyan; Pillai, Radhakrishna G.; Sergi, George (1 October 2021). "Long-term performance of galvanic anodes for the protection of steel reinforced concrete structures". Journal of Building Engineering. 42 103049. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103049.

- ^ "Corrosion - Properties of metals - National 4 Chemistry Revision". BBC.

- ^ "Impressed Current Protection Anodes – Specialist Castings". 16 January 2020.

- ^ "What is an Impressed Current Anode? – Definition from Corrosionpedia".

- ^ "Powered Anode Rod Advantages | #1 Anode Rod | Corro-Protec". 13 March 2019.

External links

[edit]Anode

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Polarity

In electrochemistry, an anode is defined as the electrode at which oxidation occurs, resulting in the release of electrons from the species undergoing reaction.[1] This process distinguishes the anode from the cathode, where reduction takes place and electrons are gained.[2] The anode's role is fundamental to the directionality of electrochemical reactions, as oxidation inherently involves the loss of electrons, driving the flow of charge in the system.[4] The polarity of the anode varies depending on the type of electrochemical cell. In galvanic cells, which operate spontaneously to convert chemical energy into electrical energy, the anode serves as the negative terminal, while the cathode is the positive terminal.[10] Conversely, in electrolytic cells, where electrical energy drives a non-spontaneous reaction, the anode is the positive terminal and the cathode is negative.[11] This reversal arises because galvanic cells generate voltage internally, with electrons flowing from the anode to the cathode through the external circuit, whereas electrolytic cells require an external power source to force this flow.[12] Regarding charge flow, electrons always move from the anode to the cathode in the external circuit of both cell types, reflecting the oxidation at the anode.[13] However, conventional current, defined as the flow of positive charge, enters the anode from the external circuit in both galvanic and electrolytic setups.[14] A common mnemonic to remember the anode's identity in electrolytic cells is that anions (negatively charged ions) are attracted to the anode, where oxidation occurs.[15]Etymology

The term "anode" originates from the Ancient Greek word ἄνοδος (anodos), composed of ἀνά (ana), meaning "up" or "upward," and ὁδός (hodos), meaning "way" or "path," thus literally translating to "way up."[16] This etymological root reflects the conceptual direction of positive charge or conventional current flow in early electrochemical contexts.[16] The word was coined in 1834 by the English scientist Michael Faraday during his investigations into electrolysis, in collaboration with the polymath William Whewell, who suggested the Greek-derived terms to standardize nomenclature for electrodes.[17] Faraday first employed "anode" in his paper "Experimental Researches in Electricity: Seventh Series," published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, where he defined it as the electrode at which anions (negative ions) are attracted, or the path by which positive electricity enters the electrolyte.[18] In this work, Faraday described the anode as "the negative extremity of the decomposing body," referring to the surface where the electric current enters the electrolyte during decomposition, although in modern convention, the anode is the positive electrode in electrolytic cells. In a letter dated April 25, 1834, Whewell proposed "anode" and "cathode" to Faraday as alternatives to earlier Latin-inspired terms like "exode" and "eisode," emphasizing their suitability for the emerging field of electrochemistry.[19] The contrasting term "cathode" derives from Greek καθόδος (kathodos), meaning "way down," from κατά (kata, "down") and ὁδός (hodos, "way"), highlighting the oppositional polarity in electron or ion migration relative to the anode. Initially introduced within Faraday's framework for voltaic cells and electrolytic processes in the 19th century, the term "anode" was part of a broader set of neologisms—including "electrode," "anion," "cation," and "electrolyte"—designed to describe the phenomena of electrical decomposition without relying on ambiguous positive/negative designations.[17] Over time, "anode" evolved from its specific application in Faraday's electrolysis studies to a generalized term encompassing all electrochemical and electronic contexts where it denotes the electrode connected to the positive terminal or involved in oxidation reactions.[20] This expansion occurred throughout the 19th century as Faraday's nomenclature gained widespread adoption in scientific literature, solidifying its role in describing electrode behavior across diverse voltaic and electrolytic systems.[20]Anodes in Electrochemistry

Galvanic Cell Anode

In a galvanic cell, the anode serves as the site of oxidation during spontaneous electrochemical reactions, where chemical energy from the redox process is converted into electrical energy. This occurs as the anode material undergoes oxidation, releasing electrons that flow through the external circuit to the cathode, driving the cell's operation without external power input. The process typically involves the corrosion or dissolution of the anode material, generating electrons and positive ions that enter the electrolyte, thereby maintaining charge balance within the cell.[3] The general half-reaction at the anode in a galvanic cell can be represented as the oxidation of a metal or species:where is the anode material, is its oxidized form, and electrons are released. This reaction contrasts with the reduction at the cathode, collectively producing a net cell voltage. For instance, in the classic Daniell cell, the zinc anode undergoes oxidation according to:

releasing electrons as zinc dissolves into the electrolyte, powering the cell with a standard potential difference derived from the zinc half-cell. In primary batteries, such as the zinc-carbon cell, the zinc anode oxidizes similarly during discharge, providing electrons for the reaction while the anode material depletes over time. In rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, the anode—typically graphite intercalated with lithium—facilitates oxidation during discharge: lithium atoms are oxidized to ions, which desintercalate from the graphite structure and migrate through the electrolyte to the cathode, enabling high energy density through this reversible mechanism. The anode's reduction potential plays a key role in determining the cell's electromotive force (EMF), calculated as , where both potentials are standard reduction potentials; a more negative increases the overall cell voltage, enhancing efficiency.[21] Fuel cells extend this principle using continuous fuel supply, where the anode catalyzes the oxidation of hydrogen gas:

Electrons generated at the anode (often platinum-catalyzed) travel externally to produce electricity, while protons pass through the electrolyte to the cathode, yielding water as the byproduct in proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. This oxidation mechanism allows sustained power generation, with the anode's efficiency influenced by catalyst performance and fuel purity.[22]