Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

OpenVZ

View on Wikipedia| OpenVZ | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Developers | Virtuozzo and OpenVZ community |

| Initial release | 2005 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Linux |

| Platform | x86, x86-64 |

| Available in | English |

| Type | OS-level virtualization |

| License | GPLv2 |

| Website | openvz |

OpenVZ (Open Virtuozzo) is an operating-system-level virtualization technology for Linux. It allows a physical server to run multiple isolated operating system instances, called containers, virtual private servers (VPSs), or virtual environments (VEs). OpenVZ is similar to Solaris Containers and LXC.

OpenVZ compared to other virtualization technologies

[edit]While virtualization technologies such as VMware, Xen and KVM provide full virtualization and can run multiple operating systems and different kernel versions, OpenVZ uses a single Linux kernel and therefore can run only Linux. All OpenVZ containers share the same architecture and kernel version. This can be a disadvantage in situations where guests require different kernel versions from that of the host. However, as it does not have the overhead of a true hypervisor, it is very fast and efficient.[1]

Memory allocation with OpenVZ is soft in that memory not used in one virtual environment can be used by others or for disk caching. While old versions of OpenVZ used a common file system (where each virtual environment is just a directory of files that is isolated using chroot), current versions of OpenVZ allow each container to have its own file system.[2]

Kernel

[edit]The OpenVZ kernel is a Linux kernel, modified to add support for OpenVZ containers. The modified kernel provides virtualization, isolation, resource management, and checkpointing. As of vzctl 4.0, OpenVZ can work with unpatched Linux 3.x kernels, with a reduced feature set.[3]

Virtualization and isolation

[edit]Each container is a separate entity, and behaves largely as a physical server would. Each has its own:

- Files

- System libraries, applications, virtualized

/procand/sys, virtualized locks, etc. - Users and groups

- Each container has its own root user, as well as other users and groups.

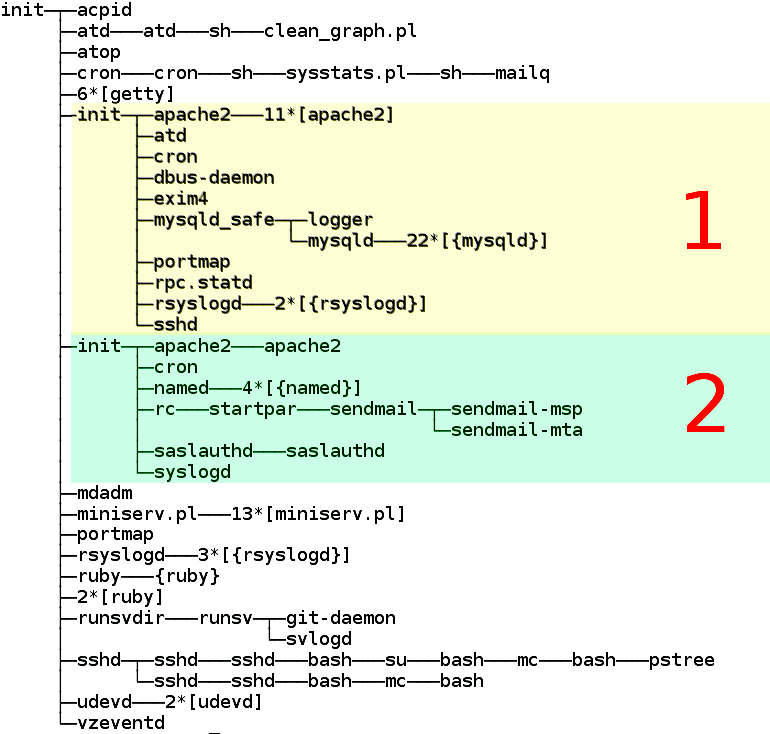

- Process tree

- A container only sees its own processes (starting from

init). PIDs are virtualized, so that the init PID is 1 as it should be. - Network

- Virtual network device, which allows a container to have its own IP addresses, as well as a set of netfilter (

iptables), and routing rules. - Devices

- If needed, any container can be granted access to real devices like network interfaces, serial ports, disk partitions, etc.

- IPC objects

- Shared memory, semaphores, messages.

Resource management

[edit]OpenVZ resource management consists of four components: two-level disk quota, fair CPU scheduler, disk I/O scheduler, and user bean counters (see below). These resources can be changed during container run time, eliminating the need to reboot.

- Two-level disk quota

- Each container can have its own disk quotas, measured in terms of disk blocks and inodes (roughly number of files). Within the container, it is possible to use standard tools to set UNIX per-user and per-group disk quotas.

- CPU scheduler

- The CPU scheduler in OpenVZ is a two-level implementation of fair-share scheduling strategy.On the first level, the scheduler decides which container it is to give the CPU time slice to, based on per-container cpuunits values. On the second level the standard Linux scheduler decides which process to run in that container, using standard Linux process priorities. It is possible to set different values for the CPUs in each container. Real CPU time will be distributed proportionally to these values. In addition, OpenVZ provides ways to set strict CPU limits, such as 10% of a total CPU time (

--cpulimit), limit number of CPU cores available to container (--cpus), and bind a container to a specific set of CPUs (--cpumask).[4] - I/O scheduler

- Similar to the CPU scheduler described above, I/O scheduler in OpenVZ is also two-level, utilizing Jens Axboe's CFQ I/O scheduler on its second level. Each container is assigned an I/O priority, and the scheduler distributes the available I/O bandwidth according to the priorities assigned. Thus no single container can saturate an I/O channel.

- User Beancounters

- User Beancounters is a set of per-container counters, limits, and guarantees, meant to prevent a single container from monopolizing system resources. In current OpenVZ kernels (RHEL6-based 042stab*) there are two primary parameters, and others are optional.[5] Other resources are mostly memory and various in-kernel objects such as Inter-process communication shared memory segments and network buffers. Each resource can be seen from

/proc/user_beancountersand has five values associated with it: current usage, maximum usage (for the lifetime of a container), barrier, limit, and fail counter. The meaning of barrier and limit is parameter-dependent; in short, those can be thought of as a soft limit and a hard limit. If any resource hits the limit, the fail counter for it is increased. This allows the owner to detect problems by monitoring /proc/user_beancounters in the container.

Checkpointing and live migration

[edit]A live migration and checkpointing feature was released for OpenVZ in the middle of April 2006. This makes it possible to move a container from one physical server to another without shutting down the container. The process is known as checkpointing: a container is frozen and its whole state is saved to a file on disk. This file can then be transferred to another machine and a container can be unfrozen (restored) there; the delay is roughly a few seconds. Because state is usually preserved completely, this pause may appear to be an ordinary computational delay.

Limitations

[edit]By default, OpenVZ restricts container access to real physical devices (thus making a container hardware-independent). An OpenVZ administrator can enable container access to various real devices, such as disk drives, USB ports,[6] PCI devices[7] or physical network cards.[8]

/dev/loopN is often restricted in deployments (as loop devices use kernel threads which might be a security issue), which restricts the ability to mount disk images. A work-around is to use FUSE.

OpenVZ is limited to providing only some VPN technologies based on PPP (such as PPTP/L2TP) and TUN/TAP. IPsec is supported inside containers since kernel 2.6.32.

A graphical user interface called EasyVZ was attempted in 2007,[9] but it did not progress beyond version 0.1. Up to version 3.4, Proxmox VE could be used as an OpenVZ-based server virtualization environment with a GUI, although later versions switched to LXC.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Performance Evaluation of Virtualization Technologies for Server Consolidation". Archived from the original on 2009-01-15.

- ^ "Ploop - OpenVZ Linux Containers Wiki". Archived from the original on 2012-03-26.

- ^ Kolyshkin, Kir (6 October 2012). "OpenVZ turns 7, gifts are available!". OpenVZ Blog. Retrieved 2013-01-17.

- ^ vzctl(8) man page, CPU fair scheduler parameters section, http://openvz.org/Man/vzctl.8#CPU_fair_scheduler_parameters Archived 2017-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "VSwap - OpenVZ Linux Containers Wiki". Archived from the original on 2013-02-13.

- ^ vzctl(8) man page, Device access management subsection, http://wiki.openvz.org/Man/vzctl.8#Device_access_management

- ^ vzctl(8) man page, PCI device management section, http://wiki.openvz.org/Man/vzctl.8#PCI_device_management

- ^ vzctl(8) man page, Network devices section, http://wiki.openvz.org/Man/vzctl.8#Network_devices_control_parameters

- ^ EasyVZ: Grafische Verwaltung für OpenVZ. Frontend für freie Linux-Virtualisierung

External links

[edit]OpenVZ

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Origins and Initial Release

OpenVZ originated as an open-source derivative of Virtuozzo, a proprietary operating system-level virtualization platform developed by SWsoft. Virtuozzo was first released in January 2002, introducing container-based virtualization for Linux servers to consolidate multiple virtual private servers (VPS) on a single physical host, thereby reducing hardware costs for hosting providers.[6][2] In 2005, SWsoft—later rebranded as Parallels and now part of the Virtuozzo ecosystem—launched OpenVZ to open-source the core components of Virtuozzo, fostering community contributions and broader adoption. The initial release made available the kernel modifications and user-space tools that enabled efficient OS-level virtualization without the resource overhead of full hardware emulation in traditional virtual machines. This move addressed the limitations of proprietary software by allowing free modification and distribution, aligning with the growing demand for cost-effective Linux-based hosting solutions.[2][6] The OpenVZ kernel patches were licensed under the GNU General Public License version 2 (GPLv2), ensuring compatibility with the Linux kernel's licensing requirements. In contrast, the user-space tools, such as utilities for container creation and management, were released under a variety of open-source licenses, primarily GPLv2 or later, but also including the BSD license and GNU Lesser General Public License version 2.1 or later for specific components. The primary goal of OpenVZ was to deliver lightweight, secure containers for Linux environments, enabling hosting providers to offer affordable VPS services with near-native performance by sharing the host kernel among isolated instances.[7][2]Key Milestones and Evolution

OpenVZ's development progressed rapidly following its initial release, with significant enhancements to core functionality. In April 2006, the project introduced checkpointing and live migration capabilities, enabling the seamless transfer of virtual environments (VEs) between physical servers without downtime.[8] This feature marked a pivotal advancement in container reliability and mobility for production environments. By 2012, with the release of vzctl 4.0, OpenVZ gained support for unpatched upstream Linux 3.x kernels, allowing users to operate containers on standard kernels with a reduced but functional feature set, thereby minimizing the need for custom patches.[9] This update, which became widely available in early 2013, broadened compatibility and eased integration with mainstream Linux distributions. The project's governance shifted in the late 2000s and 2010s following corporate changes. After Parallels acquired SWsoft in 2008, OpenVZ came under Parallels' umbrella, but development transitioned to Virtuozzo oversight starting in 2015 when Virtuozzo was spun out as an independent entity focused on container and virtualization technologies.[2] In December 2014, Parallels announced the merger of OpenVZ with Parallels Cloud Server into a unified codebase, which Virtuozzo formalized in 2016 with the release of OpenVZ 7.0, integrating KVM hypervisor support alongside containers.[6] Major OpenVZ-specific releases tapered off after 2017, with the final significant updates to the 7.x series occurring around that time, reflecting a strategic pivot toward commercial products.[10] By 2025, OpenVZ had evolved into the broader Virtuozzo Hybrid Infrastructure, a hybrid cloud platform combining containers, VMs, and storage orchestration for service providers. As of 2025, OpenVZ 9 remains in testing with pre-release versions available, though no stable release has been issued, prompting discussions on migration paths.[11][12] Community discussions in 2023 highlighted ongoing interest in future development, particularly around an OpenVZ 9 roadmap, with users inquiring about potential updates to support newer kernels and features amid concerns over the project's maintenance status.[13] In 2024, reports emerged of practical challenges, such as errors during VPS creation in OpenVZ 7 environments, including failures with package management tools like vzpkg when handling certain OS templates.[14] These issues underscored the maturing ecosystem's reliance on community patches for sustained usability.Current Status and Community Involvement

As of 2025, OpenVZ receives limited maintenance primarily through its commercial successor, Virtuozzo Hybrid Server 7, which entered end-of-maintenance in July 2024 but continues to provide security updates until its end-of-life in December 2026.[15] For instance, in July 2025, Virtuozzo issued patches addressing vulnerabilities in components such as sudo (CVE-2025-32462), rsync (CVE-2024-12085), and microcode_ctl (CVE-2024-45332), ensuring ongoing stability for kernel and related tools in hybrid infrastructure environments.[16] Similarly, kernel security updates incorporate fixes for stability and vulnerabilities across supported kernels. However, core OpenVZ versions, such as 4.6 and 4.7, reached end-of-life in 2018, with no further updates beyond that point.[15] Community involvement persists through established channels like the OpenVZ forum, which has supported users since 2010, though activity focuses more on troubleshooting legacy setups than innovation.[17] Discussions indicate a dedicated but shrinking user base, with queries in 2025 often centered on migrations to modern alternatives like LXC or KVM, as seen in September 2025 threads on platforms such as Proxmox forums.[18] A 2023 email archive from the OpenVZ users mailing list hinted at internal plans for future releases, but no public roadmap materialized, and promised advancements remain unfulfilled by late 2025.[19] Open-source contributions continue via GitHub mirrors, including active maintenance of related projects like CRIU (Checkpoint/Restore In Userspace), with commits as recent as October 29, 2025.[20] In broader 2025 analyses, OpenVZ is widely perceived as a legacy technology, overshadowed by container orchestration tools like Docker and Kubernetes, prompting many providers to phase it out—such as plans announced in 2024 to decommission OpenVZ nodes by early 2025.[12] Virtuozzo's updates to Hybrid Infrastructure 7 in 2025 serve as a partial successor, integrating container-based virtualization with enhanced storage and compute features for hybrid cloud environments, though it diverges from pure OpenVZ roots.[21] This shift underscores limited new feature development for traditional OpenVZ, with community efforts increasingly archival rather than expansive.[21]Technical Architecture

Kernel Modifications

OpenVZ relies on a modified Linux kernel that incorporates specific patches to enable OS-level virtualization, allowing multiple isolated virtual environments (VEs) to share the same kernel without significant overhead. These modifications introduce a virtualization layer that isolates key kernel subsystems, including processes, filesystems, networks, and inter-process communication (IPC), predating the native Linux namespaces introduced in later kernel versions. This layer ensures that VEs operate as independent entities while utilizing the host's kernel resources efficiently.[22] A central component of these kernel modifications is the User Beancounters (UBC) subsystem, which provides fine-grained, kernel-level accounting and control over resource usage per VE. UBC tracks and limits resources such as physical memory (including kernel-allocated pages), locked memory, pseudophysical memory (private memory pages), number of processes, and I/O operations, preventing any single VE from monopolizing host resources. For instance, parameters like kmemsize and privvmpages enforce barriers and limits to guarantee fair allocation and detect potential denial-of-service scenarios from resource exhaustion. These counters are accessible via the /proc/user_beancounters interface, where held values reflect current usage and maxheld indicates peaks over accounting periods.[23][24] Additional modifications include two-level disk quotas and a fair CPU scheduler to enhance resource management. The two-level disk quota system operates hierarchically: at the host level, administrators set per-VE limits on disk space (in blocks) and inodes using tools like vzquota, while inside each VE, standard user-level quotas can be applied independently, enabling container administrators to manage their own users without affecting the host. The fair CPU scheduler implements a two-level fair-share mechanism, where the top level allocates CPU time slices to VEs based on configurable cpuunits (shares), and the bottom level uses the standard Linux Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) within each VE for process prioritization, ensuring proportional resource distribution across VEs.[25][26] Over time, OpenVZ kernel development has evolved toward compatibility with upstream Linux kernels from the 3.x series (specifically 3.10 based on RHEL 7), by minimizing custom patches while retaining core features like UBC on dedicated stable branches (e.g., based on RHEL kernels). The current OpenVZ 7, based on RHEL 7 kernel 3.10, has end of maintenance in July 2024 and end of life in December 2026.[15] Full OpenVZ functionality, including UBC and the fair scheduler, requires these patched kernels, as many original patches influenced but were not fully merged into upstream cgroups and namespaces; as of 2025, releases focus on stability and security fixes.[27][28]Container Management and Tools

OpenVZ provides a suite of user-space tools for managing containers, known as virtual private servers (VPS) or containers (CTs), enabling administrators to create, configure, and administer them efficiently from the host system. The primary command-line utility is vzctl, which runs on the host node and allows direct operations such as creating, starting, stopping, mounting, and destroying containers, as well as configuring basic parameters like hostname and IP addresses.[29] For example, the commandvzctl create 101 --ostemplate centos-7-x86_64 initializes a new container using a specified OS template. These tools interface with the underlying kernel modifications to enforce container isolation without requiring hardware virtualization.[30]

Complementing vzctl is vzpkg, a specialized tool for handling package management within containers, including installing, updating, and removing software packages or entire application templates while maintaining compatibility with the host's package repositories.[31] It supports operations like vzpkg install 101 -p httpd to deploy applications inside a running container numbered 101, leveraging EZ templates that bundle repackaged RPM or DEB packages for seamless integration.[32] vzpkg also facilitates cache management for OS templates, ensuring efficient reuse during deployments. As reported in 2024, some deployments of OpenVZ 7 encountered issues with vzpkg clean failing to locate certain templates due to repository inconsistencies, resolvable by manual cache updates or re-downloads.[14]

Container creation in OpenVZ relies heavily on template-based provisioning, where pre-built OS images—such as variants of Ubuntu, CentOS, Debian, and Fedora—are used to rapidly deploy fully functional environments with minimal configuration.[33] Administrators download these OS templates from official repositories via commands like vzpkg [download](/page/Download) centos-7-x86_64, which populate the container's filesystem with essential system programs, libraries, and boot scripts, allowing quick instantiation of isolated Linux instances. This approach supports diverse distributions, enabling tailored deployments for specific workloads without rebuilding from scratch each time.[7]

OpenVZ integrates with third-party control panels for graphical management, notably Proxmox VE, which provided native support for OpenVZ containers through its web interface up to version 3.4 released in 2015, after which it transitioned to LXC for containerization.[34]

Isolation Mechanisms

OpenVZ employs chroot-based mechanisms to isolate the file systems of containers, restricting each container's processes to a dedicated subdirectory within the host's file system, thereby preventing access to files outside this boundary. This approach, an enhanced form of the standard Linux chroot syscall, ensures that containers operate as if they have their own root directory while sharing the host's kernel and libraries for efficiency. Bind mounts are utilized to selectively expose host resources, such as the kernel binaries and essential system files, without compromising the overall isolation.[35][36] For process and user isolation, OpenVZ leverages namespaces to create independent views of system resources for each container. Process namespaces assign unique process IDs (PIDs) within a container, making its processes invisible and inaccessible from other containers or the host, with the container's init process appearing as PID 1 internally. User namespaces map container user and group IDs to distinct host IDs, allowing root privileges inside the container without granting them on the host. Prior to native Linux kernel support in version 3.8 (introduced in 2013), these namespaces were emulated through custom patches in the OpenVZ kernel to provide similar isolation semantics; subsequent versions integrate mainline kernel features for broader compatibility and reduced maintenance.[35][37][38] Network isolation in OpenVZ is achieved using virtual Ethernet (veth) devices, which form paired interfaces linking the container's network stack to a bridge on the host, enabling Layer 2 connectivity while maintaining separation. Each container operates in its own private IP address space, complete with independent routing tables, firewall rules (via netfilter/iptables), and network caches, preventing interference between containers or with the host. This setup supports features like broadcasts and multicasts within the container's scope without affecting others.[39][35] Device access is strictly controlled by default to enforce isolation, with containers denied direct interaction with sensitive host hardware such as GPUs, physical network cards, or storage devices to avoid privilege escalations or resource contention. The vzdev kernel module facilitates virtual device management, and administrators can enable passthrough for specific devices using tools like vzctl with options such as --devices, allowing controlled access to hardware like USB or serial ports when required for workloads. Resource limits further reinforce these controls by capping device-related usage, though detailed accounting is handled separately.[39][40]Core Features

Resource Management Techniques

OpenVZ employs User Beancounters (UBC) as its primary mechanism for managing resources such as memory and processes across containers, providing both limits and guarantees to ensure fair allocation and prevent resource exhaustion. UBC tracks resource usage through kernel modifications that account for consumption at the container level, allowing administrators to set barriers (soft limits where usage beyond triggers warnings but not enforcement) and limits (hard caps where exceeding results in denial of service or process termination). This system is configurable via parameters in the container's configuration file and monitored through the/proc/user_beancounters interface, which reports held usage against configured thresholds.[41][42]

For memory management, UBC includes parameters like vmguarpages, which guarantees memory availability up to the barrier value in 4 KB pages, ensuring applications can allocate memory without restriction below this threshold while the limit is typically set to the maximum possible value (LONG_MAX) to avoid hard caps. Another key parameter, oomguarpages, provides out-of-memory (OOM) protection by prioritizing the container for memory reclamation up to the barrier, again with the limit set to LONG_MAX; this helps maintain service levels during host memory pressure. Memory usage is precisely tracked for parameters such as privvmpages, where the held value represents the sum of resident set size (RSS) plus swap usage, calculated as:

in 4 KB pages, enforcing barriers and limits to control private virtual memory allocations. The numproc parameter limits the total number of processes and threads per container, with barrier and limit values set identically to cap parallelism, such as restricting to around 8,000 to balance responsiveness and memory overhead.[43][42][44]

CPU resources are allocated using a two-level fair-share scheduler that distributes time slices proportionally among containers. At the first level, the scheduler assigns CPU quanta to containers based on the cpuunits parameter, where higher values grant greater shares—for instance, a container with 1000 cpuunits receives twice the allocation of one with 500 when competing for resources. The second level employs the standard Linux scheduler to prioritize processes within a container. This approach ensures equitable distribution of the host's available CPU capacity among containers.[26][45]

Disk and I/O management features two-level quotas to control storage usage and bandwidth. Container-level quotas, set by the host administrator, limit total disk space and inodes per container, while intra-container quotas allow the container administrator to enforce per-user and per-group limits using standard Linux tools like those from the quota package. For I/O, a two-level scheduler based on CFQ prioritizes operations proportionally across containers, effectively throttling bandwidth to prevent any single container from monopolizing the disk subsystem and ensuring predictable performance.[8][46][47]

Checkpointing and Live Migration

OpenVZ introduced checkpointing capabilities in April 2006 as a kernel-based extension known as Checkpoint/Restore (CPT), enabling the capture of a virtual environment's (VE) full state, including memory and process information, for later restoration on the same or different hosts.[48] This feature was designed to support live migration by minimizing service interruptions during VE relocation.[49] The checkpointing process involves three main stages: first, suspending the VE by freezing all processes and confining them to a single CPU to prevent state changes; second, dumping the kernel-level state, such as memory pages, file descriptors, and network connections, into image files; and third, resuming the VE after cleanup.[50] For live migration, the source host performs the checkpoint, transfers the image files and VE private area (using tools like rsync over the network), and the target host restores the state using compatible kernel modifications, achieving downtime typically under one second for small VEs due to the rapid freeze-dump-resume cycle. This transfer does not require shared storage, as rsync handles file synchronization, though shared storage can simplify the process for larger datasets. Subsequent development shifted toward userspace implementation with CRIU (Checkpoint/Restore In Userspace), initiated by the OpenVZ team to enhance portability and reduce kernel dependencies, with full integration in OpenVZ 7 starting around 2016.[51] CRIU dumps process states without deep kernel alterations, preserving memory, open files, and IPC objects, and supports iterative pre-copy techniques to migrate memory pages before final freeze, further reducing downtime.[52] Migration requires identical or compatible OpenVZ kernel versions between source and target hosts to ensure state compatibility, along with network connectivity for image transfer.[48] In practice, however, OpenVZ's reliance on modified older kernels (e.g., 3.10 in OpenVZ 7) limits its adoption in modern environments, where CRIU is more commonly used with upstream Linux kernels for containers like LXC or Docker.[53] Virtuozzo, the commercial successor to OpenVZ, enhanced live migration in its 7.0 Update 5 release in 2017 by improving container state preservation during transfers and adding I/O throttling for migration operations to optimize performance in hybrid setups.[54] These updates enabled seamless relocation of running containers with preserved network sessions, though full zero-downtime guarantees depend on workload size and network bandwidth.[55]Networking and Storage Support

OpenVZ provides virtual networking capabilities primarily through virtual Ethernet (veth) pairs, which consist of two connected interfaces: one on the hardware node (CT0) and the other inside the container, enabling Ethernet-like communication with support for MAC addresses.[39] These veth devices facilitate bridged networking, where container traffic is routed via a software bridge (e.g., br0) connected to the host's physical interface, allowing containers to appear as independent hosts on the network with their own ARP tables.[56] In this setup, outgoing packets from the container traverse the veth adapter to the bridge and then to the physical adapter, while incoming traffic follows the reverse path, ensuring efficient Layer 2 connectivity without the host acting as a router.[56] Containers in OpenVZ maintain private routing tables, configurable independently to support isolated network paths, such as private IP ranges with NAT for internal communication.[57] VPN support is limited and requires specific configurations; for instance, TUN/TAP devices can be enabled by loading the kernel module on the host and granting the container net_admin capabilities, allowing protocols like OpenVPN to function, though non-persistent tunnels may need patched tools.[58] Native support for TUN/TAP is not automatic and demands tweaks, while PPP-based VPNs such as PPTP and L2TP often encounter compatibility issues due to kernel restrictions and device access limitations in the container environment.[58] For storage, OpenVZ utilizes image-based disks in the ploop format, a loopback block device that stores the entire container filesystem within a single file, offering advantages over traditional shared filesystems by enabling per-container quotas and faster sequential I/O.[59] Ploop supports snapshot creation for point-in-time backups and state preservation, dynamic resizing of disk images without downtime, and efficient backup operations through features like copy-on-write.[59] This format integrates with shared storage solutions, such as NFS or GFS2, where container disks can be hosted to facilitate live migration by minimizing data transfer to only modified blocks tracked during the process.[60] However, using ploop over NFS carries risks of data corruption from network interruptions, making it suitable primarily for stable shared environments.[61] Graphical user interface support for managing OpenVZ networking and storage remains basic, with the early EasyVZ tool—released around 2007 in version 0.1—providing fundamental capabilities for container creation, monitoring, and simple configuration but lacking advanced features for detailed network bridging or ploop snapshot handling.[62] No modern, comprehensive GUI has emerged as a standard for these aspects, relying instead on command-line tools like vzctl and prlctl for precise control.[62]Comparisons to Other Technologies

OS-Level vs. Hardware and Para-Virtualization

OpenVZ employs operating system-level virtualization, where multiple isolated containers, known as virtual private servers (VPSs), share a single host kernel on a Linux-based physical server. This architecture contrasts sharply with hardware virtualization solutions like KVM, which utilize a hypervisor to emulate hardware and run independent guest kernels for each virtual machine, and para-virtualization approaches like Xen, where guest operating systems run modified kernels aware of the hypervisor or use hardware-assisted modes for full virtualization. In OpenVZ, the absence of a hypervisor layer and hardware emulation means all containers operate directly on the host's kernel, enforcing Linux-only support since non-Linux guests cannot utilize the shared kernel.[7][63][1] The shared kernel model in OpenVZ introduces specific compatibility requirements: all containers must use the same kernel version as the host, limiting guests to Linux distributions compatible with that version and preventing the deployment of newer kernel variants or custom modifications without affecting the entire system. In comparison, KVM allows unmodified guest kernels, supporting a wide range of operating systems including Windows and various Linux versions independently of the host kernel, while Xen enables para-virtualized guests with modified kernels for efficiency or full virtualization for unmodified ones, accommodating diverse OSes like Linux, Windows, and BSD without host kernel alignment. This kernel independence in hardware and para-virtualization provides greater flexibility for heterogeneous environments but at the cost of added complexity in managing multiple kernel instances.[7][63][64] Performance-wise, OpenVZ achieves near-native efficiency with only 1-2% CPU overhead, as containers access hardware and system resources directly without the intervention of a hypervisor or emulation layer, making it particularly suitable for Linux workloads requiring maximal resource utilization. Hardware virtualization with KVM, leveraging CPU extensions like Intel VT-x or AMD-V, incurs a typically low but measurable overhead—often around 5-10% for CPU-intensive tasks under light host loads—due to the hypervisor's scheduling and context-switching demands, though this can vary to 0-30% depending on workload and configuration. Para-virtualization in Xen reduces overhead further by allowing guests to make hypercalls directly, approaching native performance in aware guests, but still introduces some latency from hypervisor mediation compared to OpenVZ's seamless kernel sharing.[7][65][66]Efficiency and Use Case Differences

OpenVZ excels in resource efficiency through its OS-level virtualization approach, enabling high container density with hundreds of isolated environments per physical host on standard hardware.[67] This capability arises from minimal overhead, as containers share the host kernel without emulating hardware or running separate OS instances, resulting in near-native performance and reduced memory and CPU consumption compared to full virtualization solutions.[35] Such efficiency makes OpenVZ particularly suitable for homogeneous Linux workloads, where multiple similar server instances—such as web servers or databases—can operate with low resource duplication.[1] In practical use cases, OpenVZ powered the emergence of affordable VPS hosting in the mid-2000s, allowing providers to offer entry-level plans starting at around $5 per month by supporting dense deployments for web hosting and lightweight applications.[68] This contrasted with Docker's emphasis on application-centric containerization, which prioritizes portability and orchestration for microservices in development and cloud-native environments rather than full OS-level virtual servers.[69] Similarly, OpenVZ differed from VMware's hardware-assisted virtualization, which caters to enterprise needs with support for diverse operating systems but incurs higher overhead unsuitable for budget-oriented, Linux-exclusive VPS scenarios.[70] By 2025, OpenVZ's influence in democratizing access to virtual servers has waned as users migrate to successors like LXC and container orchestration tools, which offer improved isolation and broader ecosystem integration while building on its efficiency foundations.[68]Limitations and Challenges

Technical Restrictions

OpenVZ containers share the single host kernel, necessitating that all guest operating systems use user-space components compatible with the host kernel version, which for OpenVZ 7 is based on Linux kernel 3.10 from RHEL 7.[28][71] This shared kernel architecture prevents running distributions requiring kernel features introduced after 3.10, such as newer system calls or modules, thereby limiting OS diversity to older or patched variants of Linux.[4][64] By design, OpenVZ restricts container access to physical hardware devices to maintain portability and isolation, preventing direct passthrough of components like GPUs and USB devices without host modifications.[45] GPU acceleration is unavailable in containers, resulting in software rendering for graphical applications rather than hardware utilization, a limitation stemming from the absence of device isolation mechanisms in the shared kernel environment.[72] Similarly, USB device access is confined, with no standard support for passthrough to containers; while assignable in Virtuozzo's virtual machines, containers lack native integration, often requiring privileged mode or custom kernel tweaks that compromise security.[73] This hardware restriction also halts native GUI advancements, as the 3.10 kernel does not support features or drivers requiring kernel versions newer than 3.10 without external updates, confining visual applications to basic console or legacy X11 modes.[74] Advanced networking features, including VPN support via TUN/TAP interfaces, are not enabled by default and demand explicit host configuration, such as adjusting container parameters with tools likeprlctl or vzctl to grant device permissions.[58] Without these modifications, containers cannot create or manage TUN/TAP devices, leading to failures in establishing tunnels for protocols like OpenVPN or IPsec, as the shared kernel enforces restrictions to prevent resource contention.[75][76]

In OpenVZ 7, compatibility with newer distributions like Ubuntu 18.04 and later presents challenges due to the fixed 3.10 kernel, which lacks support for modern user-space requirements such as updated glibc versions or systemd behaviors.[14] Templates for Ubuntu 18.04 exist but have encountered creation errors, such as missing package dependencies during vzpkg operations, often resolved only through manual template rebuilding.[14] Upgrading containers from Ubuntu 16.04 to 18.04 or higher is infeasible without host kernel changes, as newer distros assume kernel capabilities unavailable in 3.10.[77] As of 2024, the Ubuntu 24.04 template was introduced for OpenVZ 7.0.22, but early deployments faced systemd daemon-reexec issues causing unit tracking failures, necessitating libvzctl updates and container restarts for stability.[78]