Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Namespace

View on WikipediaIn computing, a namespace is a set of signs (names) that are used to identify and refer to objects of various kinds. A namespace ensures that all of a given set of objects have unique names so that they can be easily identified.

Namespaces are commonly structured as hierarchies to allow reuse of names in different contexts. As an analogy, consider a system of naming of people where each person has a given name, as well as a family name shared with their relatives. If the first names of family members are unique only within each family, then each person can be uniquely identified by the combination of first name and family name; there is only one Jane Doe, though there may be many Janes. Within the namespace of the Doe family, just "Jane" suffices to unambiguously designate this person, while within the "global" namespace of all people, the full name must be used.

Prominent examples for namespaces include file systems, which assign names to files.[1] Some programming languages organize their variables and subroutines in namespaces.[2][3][4] Computer networks and distributed systems assign names to resources, such as computers, printers, websites, and remote files. Operating systems can partition kernel resources by isolated namespaces to support virtualization containers.

Similarly, hierarchical file systems organize files in directories. Each directory is a separate namespace, so that the directories "letters" and "invoices" may both contain a file "to_jane".

In computer programming, namespaces are typically employed for the purpose of grouping symbols and identifiers around a particular functionality and to avoid name collisions between multiple identifiers that share the same name.

In networking, the Domain Name System organizes websites (and other resources) into hierarchical namespaces.

Name conflicts

[edit]Element names are defined by the developer. This often results in a conflict when trying to mix XML documents from different XML applications.

This XML carries HTML table information:

<table>

<tr>

<td>Apples</td>

<td>Oranges</td>

</tr>

</table>

This XML carries information about a table (i.e. a piece of furniture):

<table>

<name>Mahogany Coffee Table</name>

<width>80</width>

<length>120</length>

</table>

If these XML fragments were added together, there would be a name conflict. Both contain a <table>...</table> element, but the elements have different content and meaning.

An XML parser will not know how to handle these differences.

Solution via prefix

[edit]Name conflicts in XML can easily be avoided using a name prefix.

The following XML distinguishes between information about the HTML table and furniture by prefixing "h" and "f" at the beginning of the elements.

<h:table>

<h:tr>

<h:td>Apples</h:td>

<h:td>Oranges</h:td>

</h:tr>

</h:table>

<f:table>

<f:name>Mahogany Coffee Table</f:name>

<f:width>80</f:width>

<f:length>120</f:length>

</f:table>

Naming system

[edit]A name in a namespace consists of a namespace name and a local name.[5][6] The namespace name is usually applied as a prefix to the local name.

In augmented Backus–Naur form:

name = <namespace name> separator <local name>

When local names are used by themselves, name resolution is used to decide which (if any) particular name is alluded to by some particular local name.

Examples

[edit]| Context | Name | Namespace name | Local name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain name | www.example.com | example.com (domain name) | www (subdomain name) |

| Wikipedia | Talk:Mona Lisa | Talk | Mona Lisa |

| Path (UNIX) | /home/admin/Documents/readme.txt | /home/admin/Documents (directory) | readme.txt (file name) |

| Path (Windows) | C:\Users\Admin\Documents\readme.txt | C:\Users\Admin\Documents (directory) | readme.txt (file name) |

| C++ standard library namespace | std::chrono::system_clock |

std::chrono (C++ namespace) |

system_clock (class)

|

| C++ namespace | Poco::Net::HTTPClientSession |

Poco::Net (C++ namespace) |

HTTPClientSession (class)

|

| C# namespace | System.Collections.Generic.Dictionary |

System.Collections.Generic (C# namespace) |

Dictionary (class)

|

| Java standard library package | java.util.Date |

java.util (Java package) |

Date (class)

|

| Java package | org.apache.commons.math3.special.Gamma |

org.apache.commons.math3.special (Java package) |

Gamma (class)

|

| UN/LOCODE | US NYC | US (country or territory) | NYC (locality) |

| XML | xmlns:xhtml="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" <xhtml:body> |

xhtml (previously declared XML namespace xhtml="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml") |

body (element)

|

| Perl | $DBI::errstr |

$DBI (Perl module) |

errstr (variable)

|

| Uniform Resource Name (URN) | urn:nbn:fi-fe19991055 | urn:nbn (National Bibliography Numbers) | fi-fe19991055 |

| Handle System | 10.1000/182 | 10 (handle naming authority) | 1000/182 (handle local name) |

| Digital object identifier | 10.1000/182 | 10.1000 (publisher) | 182 (publication) |

| MAC address | 01-23-45-67-89-ab | 01-23-45 (organizationally unique identifier) | 67-89-ab (NIC specific) |

| PCI ID | 1234 abcd | 1234 (vendor ID) | abcd (device ID) |

| USB VID/PID | 2341 003f[7] | 2341 (vendor ID) | 003f (product ID) |

| SPARQL | dbr:Sydney |

dbr (previously declared ontology, e.g. by specifying @prefix dbr: <http://dbpedia.org/resource/>) |

Sydney

|

Delegation

[edit]Delegation of responsibilities between parties is important in real-world applications, such as the structure of the World Wide Web. Namespaces allow delegation of identifier assignment to multiple name issuing organisations whilst retaining global uniqueness.[8] A central Registration authority registers the assigned namespace names allocated. Each namespace name is allocated to an organisation which is subsequently responsible for the assignment of names in their allocated namespace. This organisation may be a name issuing organisation that assign the names themselves, or another Registration authority which further delegates parts of their namespace to different organisations.

Hierarchy

[edit]A naming scheme that allows subdelegation of namespaces to third parties is a hierarchical namespace.

A hierarchy is recursive if the syntax for the namespace names is the same for each subdelegation. An example of a recursive hierarchy is the Domain name system.

An example of a non-recursive hierarchy are Uniform Resource Name representing an Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) number.

| Registry | Registrar | Example Identifier | Namespace name | Namespace |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Resource Name (URN) | Internet Assigned Numbers Authority | urn:isbn:978-3-16-148410-0 | urn | Formal URN namespace |

| Formal URN namespace | Internet Assigned Numbers Authority | urn:isbn:978-3-16-148410-0 | ISBN | International Standard Book Numbers as Uniform Resource Names |

| International Article Number (EAN) | GS1 | 978-3-16-148410-0 | 978 | Bookland |

| International Standard Book Number (ISBN) | International ISBN Agency | 3-16-148410-X | 3 | German-speaking countries |

| German publisher code | Agentur für Buchmarktstandards | 3-16-148410-X | 16 | Mohr Siebeck |

Namespace versus scope

[edit]A namespace name may provide context (scope in computer science) to a name, and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. However, the context of a name may also be provided by other factors, such as the location where it occurs or the syntax of the name.

| Without a namespace | With a namespace | |

|---|---|---|

| Local scope | Vehicle registration plate | Filesystem Hierarchy Standard |

| Global scope | Universally unique identifier | Domain Name System |

In programming languages

[edit]For many programming languages, namespace is a context for their identifiers. In an operating system, an example of namespace is a directory. Each name in a directory uniquely identifies one file or subdirectory.[9]

As a rule, names in a namespace cannot have more than one meaning; that is, different meanings cannot share the same name in the same namespace. A namespace is also called a context, because the same name in different namespaces can have different meanings, each one appropriate for its namespace.

Following are other characteristics of namespaces:

- Names in the namespace can represent objects as well as concepts, be the namespace a natural or ethnic language, a constructed language, the technical terminology of a profession, a dialect, a sociolect, or an artificial language (e.g., a programming language).

- In the Java programming language, identifiers that appear in namespaces have a short (local) name and a unique long "qualified" name for use outside the namespace.

- Some compilers (for languages such as C++) combine namespaces and names for internal use in the compiler in a process called name mangling.

As well as its abstract language technical usage as described above, some languages have a specific keyword used for explicit namespace control, amongst other uses. Below is an example of a namespace in C++:

import std;

// This is how one brings a name into the current scope. In this case, it's

// bringing them into global scope.

using std::println;

namespace box1 {

constexpr int BOX_SIDE = 4;

}

namespace box2 {

constexpr int BOX_SIDE = 12;

}

int main() {

constexpr int BOX_SIDE = 42;

println("{}", box1::BOX_SIDE); // Outputs 4.

println("{}", box2::BOX_SIDE); // Outputs 12.

println("{}", BOX_SIDE); // Outputs 42.

}

Computer-science considerations

[edit]A namespace in computer science (sometimes also called a name scope) is an abstract container or environment created to hold a logical grouping of unique identifiers or symbols (i.e. names). An identifier defined in a namespace is associated only with that namespace. The same identifier can be independently defined in multiple namespaces. That is, an identifier defined in one namespace may or may not have the same meaning as the same identifier defined in another namespace. Languages that support namespaces specify the rules that determine to which namespace an identifier (not its definition) belongs.[10]

This concept can be illustrated with an analogy. Imagine that two companies, X and Y, each assign ID numbers to their employees. X should not have two employees with the same ID number, and likewise for Y; but it is not a problem for the same ID number to be used at both companies. For example, if Bill works for company X and Jane works for company Y, then it is not a problem for each of them to be employee #123. In this analogy, the ID number is the identifier, and the company serves as the namespace. It does not cause problems for the same identifier to identify a different person in each namespace.

In large computer programs or documents it is common to have hundreds or thousands of identifiers. Namespaces (or a similar technique, see Emulating namespaces) provide a mechanism for hiding local identifiers. They provide a means of grouping logically related identifiers into corresponding namespaces, thereby making the system more modular.

Data storage devices and many modern programming languages support namespaces. Storage devices use directories (or folders) as namespaces. This allows two files with the same name to be stored on the device so long as they are stored in different directories. In some programming languages (e.g. C++, Python), the identifiers naming namespaces are themselves associated with an enclosing namespace. Thus, in these languages namespaces can nest, forming a namespace tree. At the root of this tree is the unnamed global namespace.

Use in common languages

[edit]C

[edit]It is possible to use anonymous structs as namespaces in C since C99.

Math.h:

#pragma once

const struct {

double PI;

double (*sin)(double);

} Math;

Math.c:

#include <math.h>

static double _sin(double arg) {

return sin(arg);

}

const struct {

double PI;

double (*sin)(double);

} Math = { M_PI, _sin };

Main.c:

#include <stdio.h>

#include "Math.h"

int main() {

printf("sin(0) = %d\n", Math.sin(0));

printf("pi is %f\n", Math.PI);

}

C++

[edit]In C++, a namespace is defined with a namespace block.[11]

namespace abc {

int bar;

}

Within this block, identifiers can be used exactly as they are declared. Outside of this block, the namespace specifier must be prefixed. For example, outside of namespace abc, bar must be written abc::bar to be accessed. C++ includes another construct that makes this verbosity unnecessary. By adding the line

using namespace abc;

to a piece of code, the prefix abc:: is no longer needed.

Identifiers that are not explicitly declared within a namespace are considered to be in the global namespace.

int foo;

These identifiers can be used exactly as they are declared, or, since the global namespace is unnamed, the namespace specifier :: can be prefixed. For example, foo can also be written ::foo.

Namespace resolution in C++ is hierarchical. This means that within the hypothetical namespace food::soup, the identifier Chicken refers to food::soup::Chicken. If food::soup::Chicken doesn't exist, it then refers to food::Chicken. If neither food::soup::Chicken nor food::Chicken exist, Chicken refers to ::Chicken, an identifier in the global namespace.

Namespaces in C++ are most often used to avoid naming collisions. Although namespaces are used extensively in recent C++ code, most older code does not use this facility because it did not exist in early versions of the language. For example, the entire C++ Standard Library is defined within namespace std, but before standardization many components were originally in the global namespace. The using statement can be used to import a symbol into the current scope.

The use of the using statements in headers for reasons other than backwards compatibility (e.g., convenience) is considered to be against good code practices, as those using statements propagate into all translation units that include the header. However, modules do not export using statements unless explicitly marked export, making using statements safer to use. For instance, one can import a module org.wikipedia.project.util with matching namespace org::wikipedia::project::util and then use using statements on symbols from that namespace to simplify verbose namespaces. Note that unlike other languages like Java or Rust, C++ modules, namespaces and source file structure do not necessarily match, though it is convention to match them for clarity (for example, module abc.def.uvw.XYZ matches namespaced class abc::def::uvw::XYZ and resides in file abc/def/uvw/XYZ.cppm).

using should be used to simplify verbose nested namespaces when modular translation units are used.

export module org.wikipedia.project.App;

import std;

import org.wikipedia.project.fs;

import org.wikipedia.project.util;

using org::wikipedia::project::fs::File;

using org::wikipedia::project::util::ConfigLoader;

using org::wikipedia::project::util::logging::Logger;

using org::wikipedia::project::util::logging::LoggerFactory;

export namespace org::wikipedia::project {

class App {

private:

Logger logger;

// private fields and methods

public:

App():

logger{LoggerFactory::getLogger("Main")} {

ConfigLoader cl(File("config/config_file.txt"));

logger.log("Application starting...");

// rest of code

}

};

}

C++11 introduces inline namespaces, which is such that its members are treated as if they are also members of the enclosing namespace. It is declared by writing inline namespace. It is akin to an implicit using namespace statement, meaning qualifying symbols in it is optional.

The inline property is transitive. If a namespace a contains an inline namespace b, which in turn contains another inline namespace c, then members of c can be accessed as if they were members of a or b.

A primary use case for inline namespaces is ABI compatibility and versioning. By placing different versions of an API within distinct inline namespaces (e.g., v1, v2), and then making the currently desired version inline, library developers can manage ABI compatibility. When a new version is released, the inline keyword can be moved to the new version's namespace, allowing users to automatically link against the new version while still enabling access to older versions through explicit qualification.

namespace mylib::utils {

namespace v1 {

void func() {

// Old implementation

}

}

// v2 is the currently active version

inline namespace v2 {

void func() {

// New implementation

}

}

}

int main() {

// Calls mylib::utils::v2::func() implicitly

mylib::utils::func();

// Calls mylib::utils::v2::func() explicitly

mylib::utils::v2::func();

// Calls mylib::utils::v1::func() explicitly

mylib::utils::v1::func();

return 0;

}

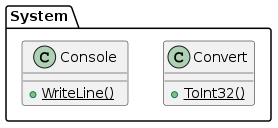

C#

[edit]Namespaces are heavily used in C# language. All .NET Framework classes are organized in namespaces, to be used more clearly and to avoid chaos. Furthermore, custom namespaces are extensively used by programmers, both to organize their work and to avoid naming collisions. When referencing a class, one should specify either its fully qualified name, which means namespace followed by the class name:

System.Console.WriteLine("Hello World!");

int i = System.Convert.ToInt32("123");

or add a using statement. This eliminates the need to mention the complete name of all classes in that namespace.

using System;

Console.WriteLine("Hello World!");

int i = Convert.ToInt32("123");

In the above examples, System is a namespace, and Console and Convert are classes defined within System.

Unlike C++, using can only import all symbols in a namespace (much like using namespace from C++, use * in Rust, or import * in Java). It cannot be used to import individual symbols and classes like it is used in Java.

namespace Wikipedia.Project;

using System;

using System.IO;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

using Wikipedia.Project.Utility;

class App

{

private static ILogger<Program> logger;

public App()

{

ConfigLoader cl = new ConfigLoader(Path.Combine("config", "config_file.txt"));

LoggerFactory loggerFactory = LoggerFactory.Create(builder =>

{

builder.AddConsole();

});

logger = loggerFactory.CreateLogger<Program>();

logger.LogInformation("Application starting...");

// rest of code

}

}

Unlike C++, C# namespaces do not allow relative referencing of symbols. For example, the class Foo.Bar.Baz.Qux cannot be referred to as Baz.Qux even if referred to from within namespace Foo.Bar: either the namespace Foo.Bar.Baz must be imported to refer to class Qux, or Foo.Bar.Baz.Qux must be fully qualified.

Java

[edit]In Java, the idea of a namespace is embodied in Java packages. All code belongs to a package, although that package need not be explicitly named. Code from other packages is accessed by prefixing the package name before the appropriate identifier, for example class String in package java.lang can be referred to as java.lang.String (this is known as the fully qualified class name). Like C++, Java offers a construct that makes it unnecessary to type the package name (import). However, certain features (such as reflection) require the programmer to use the fully qualified name.

Unlike C++, namespaces in Java are not hierarchical as far as the syntax of the language is concerned. However, packages are named in a hierarchical manner. For example, all packages beginning with java are a part of the Java platform—the package java.lang contains classes core to the language, and java.lang.reflect contains core classes specifically relating to reflection.

In Java (and Ada, C#, and others), namespaces/packages express semantic categories of code. For example, in C#, namespace System contains code provided by the system (the .NET Framework). How specific these categories are and how deep the hierarchies go differ from language to language.

Function and class scopes can be viewed as implicit namespaces that are inextricably linked with visibility, accessibility, and object lifetime.

In Java, packages cannot be partially qualified like they can in C++. For instance, it is not possible to import the java namespace and then refer to java.util.ArrayList as util.ArrayList. Symbols must either be fully qualified or imported completely into scope. import statements are not transitive nor can they be deliberately marked export like in C++. All import statements must appear at the beginning of the file, and cannot be written at any other scope. This is in contrast to C++, where the std namespace can be imported by writing using namespace std;, and then std::chrono::system_clock can be referred to as chrono::system_clock.

package org.wikipedia.project;

import java.nio.file.Paths;

import java.util.logging.Level;

import java.util.logging.Logger;

import org.wikipdia.project.util.ConfigLoader;

public class App {

private static final Logger logger = Logger.getLogger(Main.class.getName());

public App() {

ConfigLoader cl = new ConfigLoader(Paths.get("config/config_file.txt"));

logger.log(Level.INFO, "Application starting...");

// rest of code

}

}

Because Java does not support independent functions outside of classes, static class methods and so-called "utility classes" (classes with private constructors and all methods and fields static) are the equivalent to C++-style namespaces. Some examples are java.lang.Math, which contains the constants like Math.PI and methods like Math.sin().

import statements can be used to import all symbols in a package, called a glob import, which is similar to using namespace in C++. For instance, writing import java.util.*; imports all classes in the java.util package. This however, can cause symbol pollution within a file. Furthermore, using glob import statements on packages that have classes with the same name can cause ambiguity, and will fail to compile. However, java.lang.* is implicitly imported into all Java source files by default.

import java.sql.*; // Imports all classes in java.sql, including java.sql.Date

import java.util.*; // Imports all classes in java.util, including java.util.Date

Date d = new Date(); // Ambiguous Date reference resulting in compilation error

// Instead, the fully-qualified names must be used:

java.sql.Date sqlDate = new java.sql.Date(System.currentTimeMillis());

java.util.Date utilDate = new java.util.Date();

PHP

[edit]Namespaces were introduced into PHP from version 5.3 onwards. Naming collision of classes, functions and variables can be avoided. In PHP, a namespace is defined with a namespace block.

# File phpstar/foobar.php

namespace phpstar;

class FooBar

{

public function foo(): void

{

echo 'Hello world, from function foo';

}

public function bar(): void

{

echo 'Hello world, from function bar';

}

}

We can reference a PHP namespace with the following different ways:

# File index.php

# Include the file

include "phpstar/foobar.php";

# Option 1: directly prefix the class name with the namespace

$obj_foobar = new \phpstar\FooBar();

# Option 2: import the namespace

use phpstar\FooBar;

$obj_foobar = new FooBar();

# Option 2a: import & alias the namespace

use phpstar\FooBar as FB;

$obj_foobar = new FB();

# Access the properties and methods with regular way

$obj_foobar->foo();

$obj_foobar->bar();

Python

[edit]In Python, namespaces are defined by the individual modules, and since modules can be contained in hierarchical packages, then namespaces are hierarchical too.[12][13] In general when a module is imported then the names defined in the module are defined via that module's namespace, and are accessed in from the calling modules by using the fully qualified name.

# assume ModuleA defines two functions : func1() and func2() and one class : Class1

import ModuleA

ModuleA.func1()

ModuleA.func2()

a: ModuleA.Class1 = Modulea.Class1()

The from ... import ... statement can be used to insert the relevant names directly into the calling module's namespace, and those names can be accessed from the calling module without the qualified name:

# assume ModuleA defines two functions : func1() and func2() and one class : Class1

from ModuleA import func1

func1()

func2() # this will fail as an undefined name, as will the full name ModuleA.func2()

a: Class1 = Class1() # this will fail as an undefined name, as will the full name ModuleA.Class1()

Since this directly imports names (without qualification) it can overwrite existing names with no warnings.

A special form of the statement is from ... import * which imports all names defined in the named package directly in the calling module's namespace. Use of this form of import, although supported within the language, is generally discouraged as it pollutes the namespace of the calling module and will cause already defined names to be overwritten in the case of name clashes,[14] though using from import in Python can simplify verbose namespaces, such as nested namespaces.

from selenium.webdriver import Firefox

from selenium.webdriver.common.action_chains import ActionChains

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

from selenium.webdriver.common.keys import Keys

from selenium.webdriver.remote.webelement import WebElement

if __name__ == "__main__":

driver: Firefox = Firefox()

element: WebElement = driver.find_element(By.ID, "myInputField")

element.send_keys(f"Hello World{Keys.ENTER}")

action: ActionChains = ActionChains(driver)

action.key_down(Keys.CONTROL).send_keys('a').key_up(Keys.CONTROL).perform()

Python also supports import x as y as a way of providing an alias or alternative name for use by the calling module:

import numpy as np

from numpy.typing import NDArray, float32

a: NDArray[float32] = np.arange(1000)

Rust

[edit]In Rust, a namespace is called a "module" and declared using mod. Symbols inside the module are by default private, and cannot be accessed externally, unless declared with the pub keyword which exposes them. Modules can have sub-modules inside of them, allowing for nested namespaces.

Similar to the using keyword in C++, Rust has the use keyword to import symbols into the current scope.

mod my_module {

pub trait Greet {

fn greet(&self);

}

pub struct Person {

pub name: String,

}

impl Greet for Person {

fn greet(&self) {

println!("Hello, {}!", self.name);

}

}

}

fn main() {

use my_module::{Person, Greet};

let person = Person { name: String::from("Alice") };

person.greet();

}

Writing mod util; indicates to the compiler to find either a file named util.rs or util/mod.rs. crate in a use statement refers to the root of the current "crate" (project), while super can be used to refer to the parent module.

mod util;

use std::fs::File;

use crate::util::ConfigLoader;

use crate::util::logging::{Logger, LoggerFactory};

pub struct App {

config_loader: ConfigLoader;

}

impl App {

pub fn new() -> Self {

config_loader = ConfigLoader::new(File::open("config/config_file.txt"));

config_loader.load();

let logger: Logger = LoggerFactory::get_logger("Main");

logger.log("Application starting...");

// rest of code

}

}

The use keyword in Rust is more versatile than its counterpart using in C++. In addition to importing single symbols, symbol aliasing with as and glob imports, use can import multiple symbols on the same line using braces (which may be nested), import individual namespaces, and do all of the above in a single statement. This is an example of using all of the above:

use std::{

fmt::*, // imports all symbols in std::fmt

fs::{File, Metadata}, // imports std::fs::File and std::fs::Metadata

io::{prelude::*, BufReader, BufWriter} // imports all symbols in std::io::prelude::*, std::io::BufReader, and std::io::BufWriter

process, // imports the std::process namespace (for example std::process::Command can be referred to as process::Command)

time // imports the std::time namespace

};

XML namespace

[edit]In XML, the XML namespace specification enables the names of elements and attributes in an XML document to be unique, similar to the role of namespaces in programming languages. Using XML namespaces, XML documents may contain element or attribute names from more than one XML vocabulary.

SAP Namespace

[edit]In SAP systems (especially ABAP environments), namespaces are used to prevent naming collisions between standard SAP-delivered objects and customer or partner developments.[15]

A namespace identifier is delimited with “/” (for example `/MYNS/`) and is reserved via SAP’s namespace registration process. Once reserved, objects created under that namespace are uniquely identifiable and protected from unintended overwrite by SAP upgrades or imports.[16]

In modern SAP landscapes (such as ABAP in the cloud and HDI containers), namespaces are also used to semantically group development artifacts or bundles.

Emulating namespaces

[edit]In programming languages lacking language support for namespaces, namespaces can be emulated to some extent by using an identifier naming convention. For example, C libraries such as libpng often use a fixed prefix for all functions and variables that are part of their exposed interface. Libpng exposes identifiers such as:

png_create_write_struct png_get_signature png_read_row png_set_invalid

This naming convention provides reasonable assurance that the identifiers are unique and can therefore be used in larger programs without naming collisions.[17] Likewise, many packages originally written in Fortran (e.g., BLAS, LAPACK) reserve the first few letters of a function's name to indicate the group to which the function belongs.

This technique has several drawbacks:

- It doesn't scale well to nested namespaces; identifiers become excessively long since all uses of the identifiers must be fully namespace-qualified;

- Individuals or organizations may use inconsistent naming conventions, potentially introducing unwanted obfuscation;

- Compound or "query-based" operations on groups of identifiers, based on the namespaces in which they are declared, are rendered unwieldy or unfeasible;

- In languages with restricted identifier length, the use of prefixes limits the number of characters that can be used to identify what the function does; this is a particular problem for packages originally written in FORTRAN 77, which offered only 6 characters per identifier; for example, the name of the BLAS function

DGEMMindicates that it operates on double-precision floating-point numbers (D) and general matrices (GE), with only the last two characters (MM) showing what it actually does: matrix–matrix multiplication.

It also has a few advantages:

- No special software tools are required to locate names in source-code files; a simple program like grep suffices;

- There are no namespace-related name conflicts;

- There is no need for name mangling, and thus no potential incompatibility problems.

See also

[edit]- 11-digit delivery point ZIP code

- Binomial nomenclature (genus-species in biology)

- Chemical nomenclature

- Dewey Decimal Classification

- Digital object identifier

- Domain Name System

- Fourth wall

- Identity (object-oriented programming)

- Library of Congress Classification

- Star catalogues and astronomical naming conventions

- Violation of abstraction level

- XML namespace

- Argument-dependent name lookup

References

[edit]- ^ Aniket, Siddharth; Aditya, Anushka; Deepa, Chaya; Cermak, Batman; Chaiken, Ronnie; Douceur, John; Howell, Jon; Lorch, Jacob; Theimer, Marvin; Wattenhofer, Roger (2002). FARSITE: Federated, Available, and Reliable Storage for an Incompletely Trusted Environment (PDF). Proc. USENIX Symp. on Operating Systems Design and Implementation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-28.

The primary construct established by a file system is a hierarchical directory namespace, which is the logical repository for files.

- ^ "C# FAQ: What is a namespace". C# Online Net. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

A namespace is nothing but a group of assemblies, classes, or types. A namespace acts as a container—like a disk folder—for classes organized into groups usually based on functionality. C# namespace syntax allows namespaces to be nested.

- ^ "An overview of namespaces in PHP". PHP Manual.

What are namespaces? In the broadest definition, namespaces are a way of encapsulating items. This can be seen as an abstract concept in many places. For example, in any operating system directories serve to group related files, and act as a namespace for the files within them.

- ^ "Creating and Using Packages". Java Documentation. Oracle.

A package is a grouping of related types providing access protection and name space management. Note that types refers to classes, interfaces, enumerations, and annotation types. Enumerations and annotation types are special kinds of classes and interfaces, respectively, so types are often referred to in this lesson simply as classes and interfaces.

[better source needed] - ^ XML Core Working Group (8 December 2009). "Namespaces in XML 1.0 (Third Edition)". W3C. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ Moats, Ryan (May 1997). "Syntax". URN Syntax. IETF. p. 1. sec. 2. doi:10.17487/RFC2141. RFC 2141. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ Stephen J. Gowdy. "List of USB ID's". 2013.

- ^ Sollins & Masinter (December 1994). "Requirements for functional capabilities". Functional Requirements for Uniform Resource Names. IETF. p. 3. sec. 2. doi:10.17487/RFC1731. RFC 1731. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ "C# FAQ: What is a namespace". C# Online Net. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

For instance, [under Windows], to access the built-in input-output (I/O) classes and members, use the System.IO namespace. Or, to access Web-related classes and members, use the System.Web namespace.

- ^ "A namespace is "a logical grouping of the names used within a program."". Webopedia.com. 10 April 2002. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ "Namespaces allow to group entities like classes, objects and functions under a name". Cplusplus.com. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ "6. Modules". The Python Tutorial. Python Software Foundation. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "Python Scopes and Namespaces". Docs.python.org. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/modules.html "in general the practice of importing * from a module or package is frowned upon"

- ^ "SAP Namespace Overview". SAPVista. Retrieved 7 October 2025.

SAP systems use namespaces to prevent naming conflicts between SAP standard objects and customer-specific developments.

- ^ "SAP Help Portal – ABAP Connectivity and Namespace Documentation". SAP Help Portal. Retrieved 7 October 2025.

In the SAP Application Interface Framework, namespaces are used for the logical structuring of objects and configurations.

- ^ Danny Kalev. "Why I Hate Namespaces". Archived from the original on 2016-07-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Namespace

View on Grokipediaxmlns declare these associations to ensure global uniqueness.[4] In distributed systems and big data contexts, namespaces distinguish metadata tags with identical names but differing meanings, often using hierarchical structures or prefixes to merge resources while preserving semantic integrity, as seen in ontologies and schema definitions.[5]

At the operating system level, particularly in Linux, namespaces wrap global system resources—such as process IDs, network stacks, or mount points—in isolated abstractions, making them appear as private instances to processes within the namespace, which is essential for containerization technologies like Docker.[6] File systems also employ namespaces through directory hierarchies, where paths provide scoped naming for files and directories, ensuring uniqueness relative to a root or mount point across storage devices.[7] Overall, namespaces enhance modularity, reusability, and isolation in complex computing environments by systematically managing name resolution.

General Concepts

Definition and Purpose

A namespace in computing is a set of unique names or identifiers contained within a specific context or domain, ensuring that each name unambiguously refers to a particular object or resource. This mechanism isolates identifiers to prevent conflicts that could arise if the same name were used for different entities across broader systems. By providing a bounded scope for names, namespaces enable clear identification and referencing of elements such as variables, files, or network resources.[1] The primary purposes of namespaces include facilitating modular organization of resources, which allows complex systems to be broken into manageable, independent components without naming overlaps. They also support scalability in large-scale environments by permitting name reuse across isolated domains, reducing the cognitive and administrative burden on developers and administrators. Additionally, namespaces promote abstraction in software design by encapsulating related identifiers, thereby enhancing maintainability and reusability while abstracting underlying complexities.[8][9] The concept of namespaces traces its origins to the 1960s in early operating systems, with pioneering implementations in Multics (Multiplexed Information and Computing Service), developed starting in 1965 by MIT, Bell Labs, and General Electric. Multics introduced a hierarchical file system featuring a global name space for processes, allowing segmented memory and files to be referenced uniquely within a structured directory tree. The term "name space" was in use in computing literature by the late 1960s, including discussions related to early operating systems like Multics. A useful analogy for namespaces is that of an operating system directory, where files with identical names can coexist in separate subdirectories without conflict, mirroring how namespaces localize uniqueness to specific contexts.[10][11][12][13]Name Conflicts and Resolution

Name conflicts in computing arise when multiple entities share the same identifier within a shared context, leading to ambiguities that must be resolved to ensure correct program or system behavior. These conflicts can be categorized as global versus local ambiguities; for instance, two functions named "print" in different modules or libraries may conflict when imported into the same scope without qualification, causing the compiler or runtime to fail to distinguish between them during reference resolution.[14][15] Such conflicts have significant impacts on software development and network operations, including runtime errors where unintended entities are accessed, complicating debugging by obscuring the source of unexpected behavior, and increasing maintenance challenges due to fragile dependencies across modules or systems.[16] In large-scale projects, these issues can propagate errors during integration, as seen in cases where module overwriting in Python ecosystems leads to misimports and hard-to-trace bugs in 3,711 analyzed GitHub projects.[16] Namespaces address these conflicts primarily through the use of prefixes, which attach domain-specific qualifiers to identifiers for disambiguation; for example, in C++, a function "f" in namespace "Q::V" is distinctly referenced as "Q::V::f" to avoid collision with a global "f".[14] Other resolution strategies include fully qualified names, which specify the complete path from the root namespace (e.g., "global::N1::N2::A" in C#), and import statements or using directives that selectively bring names into the current scope without qualification, such as "using N1;" to access types from namespace N1 directly while avoiding broader ambiguities.[15][17] A notable real-world example occurred in the 1980s with the ARPANET, where the flat namespace of the HOSTS.TXT file caused frequent name collisions as the network expanded, resulting in update delays and errors from duplicate host names like "Frodo."[18] This was resolved by introducing the Domain Name System (DNS) in 1983, which implemented hierarchical domain namespaces (e.g., "F.ISI") to allow unique identifiers within subdomains, enabling distributed management and scalability that fully replaced the problematic system by 1987.[18][19]Namespace in Naming Systems

Hierarchical Structure

In naming systems, namespaces are organized according to a hierarchical model that structures them as an inverted tree, where each node represents a domain or subdomain, and parent nodes contain child sub-namespaces. This tree-like arrangement allows for nested uniqueness, meaning that names need only be unique within their immediate parent namespace rather than globally across the entire system, such as in a progression from a root namespace to intermediate domains and then to leaf-level identifiers.[20] The hierarchical approach offers significant benefits for managing large-scale naming systems, including enhanced scalability to accommodate millions of identifiers without overwhelming central administration, support for distributed management where different portions of the tree can be handled independently, and intuitive navigation that mirrors organizational or logical groupings for easier resolution and maintenance.[20] These properties enable the system to grow efficiently as the number of resources expands, avoiding the bottlenecks inherent in non-hierarchical designs.[21] Key properties of this hierarchy include the distinction between absolute and relative naming. Absolute names specify the full path from the root to the leaf, providing unambiguous identification regardless of context, while relative names are interpreted within a current or implied parent namespace, requiring traversal from that point to resolve fully. Name resolution in the hierarchy involves traversing the tree from the root downward to the target leaf, often through iterative queries to intermediate nodes.[20] A conceptual representation of a hierarchical namespace can be visualized as follows:Root (.)

├── Parent Namespace A

│ ├── Child Namespace A1

│ │ └── Leaf Identifier X

│ └── Child Namespace A2

│ └── Leaf Identifier Y

└── Parent Namespace B

└── Child Namespace B1

└── Leaf Identifier Z

Root (.)

├── Parent Namespace A

│ ├── Child Namespace A1

│ │ └── Leaf Identifier X

│ └── Child Namespace A2

│ └── Leaf Identifier Y

└── Parent Namespace B

└── Child Namespace B1

└── Leaf Identifier Z

Delegation and Examples

Delegation in namespaces involves the transfer of authority over a sub-namespace to another organization or system, ensuring the hierarchical integrity of the overall naming structure is preserved.[22] This process allows parent entities to offload management of specific segments while maintaining a unified global namespace, as seen in distributed systems like the Domain Name System (DNS).[23] The mechanism typically relies on registrars or dedicated servers that handle subdomains, using protocols to enforce uniqueness and proper resolution. In DNS, delegation is achieved through Name Server (NS) records in the parent zone, which point to the authoritative servers for the child zone, often accompanied by glue records to resolve circular dependencies.[23] These records ensure that queries for the delegated subdomain are routed correctly without disrupting the broader hierarchy. A prominent example is DNS, where top-level domains like .com are delegated to registries such as Verisign, which in turn allow domain owners to manage subdomains like example.com.[23] The root servers delegate authority to top-level domain servers via NS records, and this cascades down, enabling scalable management across millions of domains worldwide. In XML namespaces, element and attribute names are qualified using URI references to create unique identifiers, preventing collisions in composite documents. Introduced in the 1999 W3C specification, this approach allows document authors or tools to associate names with a unique URI, such as http://example.com/schema, ensuring tag names like <book> from different vocabularies remain distinct.[24] This delegation model enables global scalability by distributing administrative responsibilities, reducing the burden on central authorities and improving resolution efficiency through localized control.[25] However, it introduces challenges such as potential fragmentation from misconfigurations or inconsistent policies across delegates, which can lead to resolution failures or security vulnerabilities if integrity mechanisms like DNSSEC are not properly implemented.[26]Namespaces in Programming

Namespace versus Scope

In programming languages, a namespace serves as a container or mapping that organizes identifiers—such as variables, functions, and types—at a global, module, or declarative level to ensure uniqueness and avoid name conflicts across larger codebases. In contrast, scope defines the textual region of code where an identifier is visible and accessible, governing its lifetime and resolution during execution or compilation. This distinction is fundamental: namespaces focus on partitioning names for modularity, while scopes manage localized visibility to prevent unintended interactions and support encapsulation.[27] For instance, a class can act as a namespace in languages like C++, where static members are stored within the class's declarative region and remain accessible globally via qualified names, such asClassName::staticMember, regardless of the current execution context. Conversely, block scope in functions limits variables to the enclosing code block, making them temporary and invisible to outer contexts; for example, a variable declared inside an if statement or loop body cannot be referenced outside that block after execution.

Although namespaces and scopes are related—since a namespace often defines the boundaries within which scopes operate—they are not synonymous, leading to common confusion. Namespaces can influence scope resolution through qualified names, which allow bypassing local scopes to access outer or module-level identifiers directly, as in C++'s scope resolution operator :: that qualifies a name to a specific namespace. However, this interaction does not equate the concepts; scopes remain tied to lexical regions, while namespaces provide persistent organizational structure.

Historically, the concept of scope emerged with lexical scoping in ALGOL 60, which introduced block structures where declarations are valid only within their enclosing block, establishing visibility rules based on static program text rather than dynamic runtime.[28] Namespaces, as formalized mechanisms for modular name separation, were later developed in languages like Modula-2 during the late 1970s, where modules provide distinct name spaces for separate compilation units, enabling larger-scale program organization beyond simple block scoping.[29]

Implementation in Languages

In C++, namespaces are implemented using thenamespace keyword, which defines a declarative region that scopes identifiers such as types, functions, and variables, as standardized in the ISO/IEC 14882:1998 (C++98) specification.[2] This feature allows developers to group related code and avoid name collisions, with access controlled via the scope resolution operator :: or using directives and declarations that bring names into the current scope without fully qualifying them each time. For example, the standard library is encapsulated in the std namespace, enabling usage like std::cout for output operations.

Java implements namespaces through packages, which organize classes and interfaces into a hierarchical structure typically mirroring the directory layout of source files, a core feature present since the language's initial public release in 1995.[30] Packages serve as namespaces by providing a unique prefix for fully qualified class names, such as java.util.[List](/page/List_of_denim_jeans_brands), and imports via import statements allow selective access to package contents, either for specific classes or the entire package (with wildcard). The Java compiler enforces package-based access control and resolution during compilation, ensuring that class loading at runtime references the correct namespace-qualified identifiers.

Python supports namespaces via its module and package system, where modules (individual .py files) and packages (directories containing an __init__.py file) create isolated name spaces that can be imported into the current program. This import mechanism, integral to Python since its early versions starting with release 0.9.1 in 1991, uses the import statement to load modules and bind their contents to the local namespace, with the __name__ attribute indicating a module's fully qualified name (e.g., __name__ == '__main__' for the entry-point script). Packages enable hierarchical organization, such as import package.module, supporting dotted notation for submodules and relative imports within the same package hierarchy.[31][32]

Across these languages, a common pattern is the use of fully qualified names to unambiguously reference identifiers, such as std::cout in C++ or java.io.File in Java, which prepends the namespace path to avoid ambiguity without imports. To mitigate verbosity, aliasing mechanisms are employed: C++ offers using namespace std; for broad access or using std::cout; for selective items; Java uses static imports, such as import static java.lang.Math.PI;, to access static members directly without qualification, or simple imports; and Python provides import numpy as np to shorten references like np.array. These patterns promote code readability while preserving namespace isolation.[2][30][31]

Performance considerations for namespaces vary by language due to resolution timing. In C++, namespace lookup occurs primarily at compile-time via the compiler's symbol table, incurring no runtime overhead beyond the initial resolution, though broad using directives can slightly increase compilation time by expanding the set of candidates during name lookup. Java's package resolution is handled at compile-time for type checking and linking, with runtime class loading using the fully qualified name for efficiency, resulting in negligible overhead after the Java Virtual Machine caches references. In Python, imports execute at runtime, involving dynamic module search and loading (e.g., via sys.path), which introduces initial overhead for the first import but subsequent accesses are fast due to caching in sys.modules; this contrasts with compile-time languages but is optimized for Python's interpreted nature.[33][31]

Emulating Namespaces

In programming languages lacking native namespace support, such as C, developers emulate namespaces primarily through naming conventions to organize identifiers and mitigate name conflicts across modules or libraries. The most prevalent technique involves prefixing function, variable, and type names with a distinctive string unique to the module or library, effectively simulating a hierarchical naming scope without language-level enforcement. This approach ensures that symbols from different sources remain distinct in the global namespace, facilitating integration of multiple components in large projects. For instance, the POSIX standard library uses prefixes like "pthread_" for threading functions (e.g., pthread_create) to distinguish them from other utilities. The GNU Coding Standards explicitly recommend this prefixing method for C libraries, advising the selection of a prefix longer than two characters, with all external symbols beginning with it to prevent collisions and improve readability. This convention not only emulates namespace isolation but also supports automated tools for symbol resolution and aids in source code navigation by indicating provenance. Examples include the zlib library's use of "z_" prefixes (e.g., z_deflateInit) and the OpenSSL library's "EVP_" for encryption functions (e.g., EVP_EncryptInit). Such practices have become de facto standards in C development, influencing projects like the Linux kernel, where subsystem-specific prefixes (e.g., "net_" for networking) are employed to manage the vast symbol space.[34] In addition to prefixes, C programmers sometimes emulate namespaces using structs to bundle related functions via pointers, creating a pseudo-module accessible through a single handle. A struct is defined containing function pointers for operations within the "namespace," and an instance of the struct serves as the entry point, allowing indirect calls that abstract the implementation. This technique, often called the "handle idiom" or "opaque pointer pattern," provides a measure of encapsulation and modularity akin to namespaces in higher-level languages. It is commonly used in libraries requiring runtime polymorphism or configuration, such as device drivers or plugin systems, where the struct instance can be initialized with context-specific behaviors. While less flexible than native namespaces due to manual pointer management, it reduces global pollution and supports multiple "instances" of the namespace.[35] Similar emulation strategies appear in other languages without built-in namespaces. In JavaScript prior to native ES6 modules, developers simulated namespaces using objects as containers for properties and methods, attaching related functions to an object literal or variable to create a scoped context. For example, a namespace object likeMyApp.Utils = { log: function() {...}, parse: function() {...} }; groups utilities under MyApp.Utils, avoiding global conflicts through property access (e.g., MyApp.Utils.log()). This object-based approach leverages JavaScript's prototypal nature for hierarchical organization and was a standard pattern in pre-modular codebases, such as jQuery plugins or YUI libraries.[36]

These emulation techniques, while effective for avoiding name clashes and promoting code organization, introduce overhead in verbosity (e.g., longer identifiers) and lack compiler enforcement, unlike native implementations in languages like C++ or Python. They remain essential in legacy or constrained environments, underscoring the value of language-level namespace support in modern designs.