Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Linux framebuffer

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The framebuffer subsystem in the Linux kernel fbdev is used to show graphics on a computer monitor, typically on the system console.[1]

It was designed as a hardware-independent API to give user space software access to the framebuffer (the part of a computer's video memory containing a current video frame) using only the Linux kernel's own basic facilities and its device file system interface, avoiding the need for libraries like SVGAlib which effectively implemented video drivers in user space.

In most applications, fbdev has been superseded by the Linux Direct Rendering Manager (DRM) subsystem, but as of 2022, several drivers provide both DRM and fbdev APIs for backwards compatibility with software that has not been updated to use the DRM system, and there are still fbdev drivers for older (mostly embedded) hardware that does not have a DRM driver.[2]

Applications

[edit]There are three applications of the Linux framebuffer:

- An implementation of text Linux console that doesn't use hardware text mode (useful when that mode is unavailable, or to overcome its restrictions on glyph size, number of code points, etc.). One popular aspect of this is the ability to have console show the Tux logo at boot up.

- A graphic output method for a display server, independent of video adapter hardware and its drivers.

- Graphic programs avoiding the overhead of the X Window System.

Examples of the third application include Linux programs such as MPlayer, links2, NetSurf, w3m, fbff,[3] fbida,[4] and fim,[5] and libraries such as GLUT, SDL (version 1.2), GTK, and Qt, which can all use the framebuffer directly.[6] This use case is particularly popular in embedded systems.

DirectFB2 is another project aimed at providing a framework for hardware acceleration of the Linux framebuffer.

There was also a windowing system called FramebufferUI (fbui) implemented in kernel space that provided a basic two-dimensional windowing experience with very little memory use.[7]

History

[edit]Linux has had generic framebuffer support since the 2.1.109 kernel.[8]

It was originally implemented to allow the kernel to emulate a text console on systems such as the Apple Macintosh that do not have a text-mode display, and was later expanded to the IBM PC compatible platform.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Frame Buffer Device, Linux Kernel Documentation

- ^ "Developer Steps up Wanting to Maintain Linux's FBDEV Subsystem".

- ^ fbff media player repository, GitHub

- ^ fbi/fbida image viewer homepage

- ^ FIM (Fbi IMproved) image viewer homepage

- ^ HiGFXback (History of graphics backends) project with the Linux Framebuffer graphics backend, GitHub

- ^ Framebuffer UI (fbui) in-kernel Linux windowing system, GitHub

- ^ Buell, Alex (5 August 2010). "Framebuffer HOWTO". tldp.org. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023 – via Internet Archive.

External links

[edit]Linux framebuffer

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

The Linux framebuffer, commonly referred to as fbdev, is a hardware-independent abstraction layer within the Linux kernel that provides access to the video memory of graphics hardware, known as the framebuffer, through character device files such as /dev/fb0.[1] This subsystem represents the framebuffer of various video hardware, allowing user-space applications to interact with it as a large memory buffer without requiring knowledge of low-level hardware specifics.[1] By standardizing access to the underlying video frame buffer, fbdev enables portable graphics operations across diverse hardware platforms.[1] The primary purpose of the Linux framebuffer is to facilitate direct graphics output from the kernel and user-space programs, bypassing the need for complex graphics libraries or architecture-specific programming modes.[1] It was originally developed to support Linux ports on systems that lack native text-mode hardware capabilities, such as early m68k-based architectures including the Apple Macintosh, where graphical output is essential for console and basic display functions.[4] This abstraction maps the video hardware's proprietary frame buffer directly to a generic memory interface, permitting applications to perform read, write, and memory-mapped operations in a consistent manner regardless of the underlying graphics controller.[1] The fbdev subsystem emerged in kernel version 2.1.107 to address these cross-platform needs.[1]Key Components

The Linux framebuffer subsystem relies on specialized drivers to interface with graphics hardware, handling initialization, mode setting, and memory mapping for the video buffer. These drivers, such as vesafb for VESA BIOS-compatible systems on Intel architectures, enable early boot graphics by leveraging BIOS extensions to activate modes like 1024x768 at 256 colors without requiring proprietary firmware. Similarly, matroxfb supports Matrox devices across Alpha, Intel, and PowerPC platforms, providing framebuffer access for a range of resolutions, including up to 1600x1200, with bit depths from 4 to 32 bits per pixel, while managing memory allocation through kernel parameters likevideo=matroxfb:mem:X to map video RAM directly into user space.[6][7] These hardware-specific drivers abstract the underlying graphics controller, ensuring the framebuffer memory is accessible as a linear block for efficient rendering.[1]

Integration with kernel modules enhances the framebuffer's utility, particularly through fbcon, the framebuffer console, which renders text in graphical modes over the framebuffer device. Fbcon operates as a display driver under the kernel's console subsystem, supporting features like variable font sizes (e.g., 8x16 pixels) and screen rotation (0°, 90°, 180°, or 270°) when compiled statically or loaded modularly via options in Device Drivers > Graphics Support.[5] It depends on an active framebuffer driver for output, transforming the raw pixel buffer into a console interface capable of multi-colored text and blending where hardware permits, thus bridging text-based interaction with graphical environments.[5][8]

The device model employs a fixed-memory mapping scheme, exposing framebuffers as character devices in the /dev filesystem, with /dev/fb0 typically designating the primary display and /dev/fb1 for secondary ones in multihead setups. This allows direct read/write access to the buffer memory— for instance, copying the framebuffer contents via cp /dev/fb0 myfile (raw pixel data)—and supports multiple independent buffers for scenarios like additional graphics cards.[1] Symbolic links such as /dev/fb0current provide backward compatibility, while the $FRAMEBUFFER environment variable enables selection of alternate devices.[1]

Color depth and modes in the framebuffer are defined through structures like fb_var_screeninfo, accommodating formats from 8-bit palette modes, which use a colormap for 256-entry color lookup, to direct 16-bit (e.g., 5-6-5 RGB), 24-bit, and 32-bit true color representations with alpha channels.[8] Variable resolutions, such as 640x480 up to 1280x1024, are configurable via ioctls without altering fixed hardware properties outlined in fb_fix_screeninfo, ensuring flexibility across diverse displays while maintaining a consistent API for pixel data.[8][1]

History

Initial Development

The Linux framebuffer subsystem originated in 1993 as a response to the challenges faced by early Linux ports to non-x86 architectures, where traditional VGA text modes were unavailable or impractical. The frame buffer device abstraction was designed by Martin Schaller in 1994 for the Linux/m68k port. Geert Uytterhoeven, a key developer in the Linux/m68k community, contributed to early ports such as the Amiga in 1994, and the subsystem was merged into the mainline kernel in version 2.1.107 on June 25, 1998. This development was primarily motivated by the need for a unified graphics abstraction layer to enable console output on hardware such as the Apple Macintosh PowerPC, Atari, and Amiga systems, which lacked standardized text modes and relied on fragmented, architecture-specific solutions.[9][10] The core motivation stemmed from the desire to replace ad-hoc libraries like SVGAlib, which were x86-centric and unsuitable for embedded or non-standard hardware ports during Linux's expansion in the late 1990s. Uytterhoeven's implementation provided a generic interface for accessing frame buffer memory, allowing applications and the kernel console to interact with diverse graphics hardware without deep architecture-specific knowledge. Early discussions on architecture-specific mailing lists, such as linux-m68k and linux-kernel, highlighted the need for this abstraction to support bitmapped consoles and simplify driver development across platforms like PowerPC and m68k. Key contributors included Martin Schaller, who conceived the original API, Roman Hodek, and Andreas Schwab, whose inputs shaped the foundational fbdev subsystem.[9][11] Early adoption focused on console functionality, with integration into the stable 2.2 kernel series expanding compatibility to x86 PCs while retaining the non-PC emphasis. This enabled features like displaying the Tux penguin boot logo on supported hardware, demonstrating the subsystem's utility for visual output during boot and runtime. The fbdev subsystem's design prioritized hardware abstraction, paving the way for broader use in early Linux distributions on diverse architectures.[9][10]Evolution and Milestones

The Linux framebuffer subsystem achieved a key milestone in the 2.4 kernel series, released in January 2001, with the addition of the VESA framebuffer driver (vesafb). This driver enabled generic support for PC graphics hardware by initializing VESA 2.0-compliant modes at boot time using BIOS routines, avoiding the need for protected-mode BIOS calls and facilitating text-mode console output in higher resolutions without proprietary drivers.[6][12] The 2.6 kernel series, beginning with its initial release in December 2003, brought substantial expansions to the framebuffer infrastructure. Enhancements included primitive multi-head support through the framebuffer console (fbcon), allowing multiple displays to be managed via a single kernel interface, as well as acceleration hints in the fbdev API for optimizing 2D operations like bit block transfers on hardware-accelerated devices.[13] Integration with input subsystems, such as evdev, also improved, enabling seamless handling of keyboards, mice, and touch inputs alongside graphics rendering. Between 2005 and 2010, the framebuffer gained prominence in embedded systems, particularly through ports to ARM architectures that supported resource-constrained devices like smartphones and single-board computers. Notable developments included framebuffer drivers for Texas Instruments OMAP processors in the BeagleBoard (2008), which provided HDMI output and accelerated graphics for development platforms, and adaptations for Nokia's Maemo-based devices like the N770 Internet Tablet (2005) and N900 smartphone (2009), emphasizing low-overhead console and UI rendering. In 2012, during the Linux Plumbers Conference, a formal call was issued to deprecate the fbdev subsystem in favor of the more advanced Direct Rendering Manager (DRM), citing fbdev's limitations in modern mode-setting and hardware acceleration; however, it was retained for legacy compatibility, with the last new fbdev driver merged in 2014.[14][15] As of 2025, the framebuffer persists in kernel 6.x series primarily for backward compatibility and embedded use cases, with ongoing maintenance patches addressing vulnerabilities like out-of-bounds writes in image blitting functions, driven by contributions from embedded Linux communities such as those supporting ARM-based industrial systems; no major new features have been added since 2015.[16][17][18]Technical Details

Architecture and API

The Linux framebuffer architecture employs a kernel-side driver model that abstracts graphics hardware into a uniform interface, enabling user-space applications to access display devices through device files such as /dev/fb0.[19] The core structure revolves around key data structures in the kernel, includingstruct fb_info for generic framebuffer instance details and operations, struct fb_var_screeninfo for configurable parameters like resolution and bit depth, and struct fb_fix_screeninfo for fixed hardware attributes like memory offset and line length.[19] User-space interaction occurs via system calls: direct memory writes through mmap() to the framebuffer buffer, and ioctl() commands for querying or setting modes and properties, ensuring hardware independence while supporting various pixel formats and visuals such as true color or pseudo color.[20]

The framebuffer API provides a set of ioctls for managing display configuration and content. For instance, FBIOGET_FSCREENINFO retrieves fixed screen information, including the physical memory start address (smem_start) and buffer length (smem_len), which are essential for mapping the framebuffer.[20] Similarly, FBIOGET_VSCREENINFO and FBIOPUT_VSCREENINFO allow querying and setting variable screen information, such as horizontal and vertical resolution (xres, yres) and bits per pixel, enabling dynamic mode adjustments.[20] Support for advanced features includes panning and tiling modes, indicated by non-zero values in xpanstep, ypanstep, and ywrapstep within fb_fix_screeninfo, which permit efficient viewport shifting without full buffer redraws on compatible hardware.[20] Colormap management is handled through ioctls like FBIOGETCMAP and FBIOPUTCMAP using struct fb_cmap, particularly for pseudo-color visuals (e.g., 8-bit palettes where each entry maps an index to RGB values), though true-color modes bypass colormaps in favor of direct pixel packing.[20]

Programming with the framebuffer typically involves opening the device, configuring it via ioctls, mapping the memory, and writing pixel data directly. A basic sequence opens /dev/fb0 with open("/dev/fb0", O_RDWR) to obtain a file descriptor, followed by ioctls to fetch screen info and compute buffer size (e.g., xres * yres * bytes_per_pixel).[21] The buffer is then mapped using mmap(NULL, screensize, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0) to gain a pointer for direct access.[20] For writing pixels in an RGB888-packed format (24 bits per pixel, often in BGR order on little-endian systems), data is stored as three bytes per pixel; a representative example sets a blue rectangle by iterating over coordinates and assigning values like *(fbp + x*3 + y*line_length) = 255 for blue, *(fbp + x*3 + 1 + y*line_length) = 0 for green, and *(fbp + x*3 + 2 + y*line_length) = 0 for red, where fbp is the mapped pointer and line_length accounts for padding.[21]

Event handling in the framebuffer subsystem focuses on output and does not include built-in support for 3D acceleration or compositing; input events, such as from keyboards or touchscreens, are integrated separately through the evdev interface via /dev/input/event* devices, allowing applications to read raw input events alongside framebuffer rendering for interactive graphics.[22]

Configuration and Usage

The Linux framebuffer is configured primarily through kernel build options and boot-time parameters, with runtime adjustments available via user-space tools and system interfaces. To enable framebuffer support, the kernel must be compiled with the CONFIG_FB option selected under Device Drivers > Graphics support in the kernel configuration menu.[1] Specific hardware drivers, such as CONFIG_FB_VESA for VESA-compatible graphics, must also be enabled to provide the necessary low-level access to video hardware.[1] Once configured, the kernel creates device nodes like /dev/fb0 upon loading the appropriate modules.[1] Boot parameters passed via the kernel command line allow fine-tuning of framebuffer behavior. For example, the video= parameter specifies the driver and mode, such as video=vesafb:ypan for enabling panning with the VESA framebuffer driver on x86 systems.[6] To disable a specific framebuffer driver if it conflicts with other graphics modesetting, video=vesafb:off can be used.[6] For Matrox hardware supporting multiple outputs, parameters like video=matroxfb:xres:1024,yres:768,depth:32 configure resolution and bit depth, with options such as outputs:101 enabling multi-head setups on cards like the G400.[7] At runtime, framebuffer modules can be loaded using modprobe, for instance modprobe fbcon to activate the framebuffer console if built as a module.[5] The current status of framebuffers is inspectable via /sys/class/graphics/fb0/, which provides attributes like resolution and virtual size.[1] Mode changes, such as adjusting resolution or timings, are handled by the fbset utility; for example, fbset -xres 1024 -yres 768 sets a 1024x768 mode on the active device. Multi-monitor configurations assign framebuffers to specific outputs through kernel command-line options tailored to the driver. With Matrox multi-head support, video=matroxfb:outputs:101,vram:16M allocates video RAM and routes CRTC1 to a secondary display like DVI.[7] Console mapping to framebuffers in such setups uses fbcon=map:01 to direct virtual console 1 to /dev/fb0 and console 2 to /dev/fb1.[5] Basic troubleshooting addresses common issues like missing device nodes. If /dev/fb0 is absent, it can be manually created with mknod /dev/fb0 c 29 0, where 29 is the major number for framebuffer devices and 0 the minor for the first framebuffer.[23] In environments using initramfs, ensure framebuffer modules are included in the initramfs image via tools like dracut or mkinitcpio to avoid delayed device availability post-boot.[5] Compatibility checks involve verifying module loading with lsmod | grep fb and reviewing dmesg for framebuffer initialization errors.[1]Applications

Console and Boot Graphics

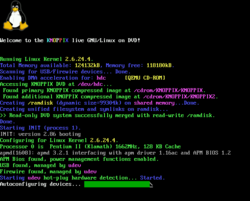

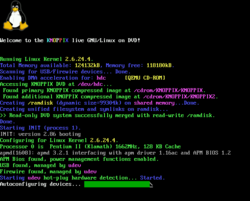

The Linux framebuffer console, known as fbcon, provides text-based console output by rendering characters directly onto the framebuffer device, enabling high-resolution display capabilities beyond traditional VGA text modes.[5] It supports Unicode text rendering with a limited set of characters, using fonts such as 10x18 or VGA8x16, which can be selected at boot via the kernel parameterfbcon=font:<name>.[5] Font configuration for virtual consoles is typically handled persistently through the /etc/vconsole.conf file, where the FONT directive specifies the desired console font, applied by systemd-vconsole-setup during early boot.[24] Additionally, fbcon employs a software cursor (softcursor) mechanism, implemented in the kernel's generic framebuffer cursor code, to overlay a blinking indicator on graphical modes without relying on hardware cursor support.

In boot processes, the framebuffer plays a key role in graphical output, particularly through tools like Plymouth, which generates splash screens by drawing directly to the framebuffer device such as /dev/fb0.[25] Plymouth replaces legacy VGA text mode output with framebuffer-rendered elements, including logos like the Tux penguin, displayed during kernel startup to provide a visually polished boot experience while occluding verbose messages.[25] The kernel itself supports boot logos via the CONFIG_LOGO configuration option, rendering the standard 224-color Linux logo (featuring Tux) onto the framebuffer early in initialization, with positioning adjustable through parameters like fbcon=logo-pos:center.[5]

For systems lacking hardware text mode support—common on modern GPUs or UEFI-based platforms—fbcon serves as a critical fallback, mapping the primary framebuffer device to the initial console via the kernel boot parameter fbcon=map:0.[5] This ensures text output remains available without reverting to unavailable legacy modes, maintaining console functionality across diverse hardware.

Performance-wise, fbcon offers faster local rendering than a serial console, which is constrained by baud rates like 115200 bits per second for remote access, as it leverages direct video memory writes for immediate display updates.[5] However, its operations are limited to basic 2D blitting for text placement and simple animations, relying on software pixel manipulation without hardware acceleration, which can result in slower scrolling compared to native VGA text mode hardware.[5]

Embedded and Specialized Systems

The Linux framebuffer has gained significant popularity in embedded systems, particularly for Internet of Things (IoT) devices, network routers with integrated displays, and ARM-based single-board computers such as early Raspberry Pi models. These platforms benefit from the framebuffer's ability to provide direct graphics access without the resource-intensive overhead of full windowing systems like X11 or Wayland, enabling lightweight graphical user interfaces (GUIs) on constrained hardware. For instance, developers often use the framebuffer device (/dev/fb0) to render simple interfaces on resource-limited ARM processors, where boot times and memory usage must be minimized.[1][18][26] In specialized applications, the framebuffer supports direct buffer access for multimedia and gaming tools, enhancing its utility in non-desktop environments. Tools like MPlayer enable video playback by outputting frames directly to the framebuffer via the -vo fbdev option, allowing efficient rendering on embedded displays without additional layers. Similarly, Fbi (and its improved variant FIM) serves as a lightweight image viewer that writes pixel data straight to the buffer, ideal for displaying static or sequential images in low-power setups. The Simple DirectMedia Layer (SDL) library further extends this by providing framebuffer backend support for games and interactive applications, facilitating cross-platform development on embedded Linux.[21][27][28] Notable examples include its integration in early versions of Android, where the framebuffer (/dev/graphics/fb0) handled basic graphics rendering before advanced compositors became standard, supporting custom ROMs and rooted devices for direct display manipulation. Custom Linux distributions for kiosks, such as those built with Yocto or Buildroot, leverage the framebuffer for fullscreen applications on touch-enabled panels, avoiding desktop environments to reduce boot times and power draw. As of 2025, the framebuffer remains relevant in legacy industrial control systems, where it drives simple HMIs on embedded panels in manufacturing and automation, as evidenced by ongoing kernel maintenance and security updates for fbdev drivers.[29][30][16] A key advantage in low-resource embedded setups is the framebuffer's minimal CPU usage for static displays or basic animations, as it allows applications to write pixel data directly to memory-mapped buffers without intermediate processing layers, conserving cycles on processors with limited performance. This direct access model ensures efficient handling of unchanging content, such as status dashboards or alert screens, making it suitable for battery-powered or always-on devices.[31][32]Limitations and Modern Context

Drawbacks and Challenges

The Linux framebuffer, or fbdev, lacks native support for hardware acceleration, relying instead on software rendering for operations such as 3D graphics, compositing, and GPU offloading. This design choice, where no generic hardware acceleration code exists in the kernel and such tasks must be handled in user space via mapped MMIO registers, results in significantly higher CPU utilization for complex graphical workloads.[3] Consequently, performance degrades notably compared to modern graphics stacks, making fbdev unsuitable for demanding applications without additional user-space optimizations.[3] Resolution and display mode support in fbdev is constrained by its dependence on legacy BIOS or VESA interfaces for mode enumeration and switching, limiting availability to predefined VESA 2.0-compliant modes such as those up to 0x31F, with manufacturer-specific extensions. This dependency often restricts higher resolutions or custom timings, particularly on non-compliant hardware, and exacerbates issues with high-DPI displays where scaling is not natively handled. Without integration with Kernel Mode Setting (KMS), fbdev struggles with multi-monitor configurations, frequently assigning incorrect resolutions or failing to coordinate across displays, as seen in cases where primary monitors receive suboptimal modes.[33] Security vulnerabilities arise from fbdev's direct memory access model, which exposes framebuffer memory without inherent sandboxing or isolation mechanisms, allowing potential unauthorized reads or writes by user-space processes or malicious drivers. A critical example is the 2025 drm/fbdev-dma flaw, where improper handling of DMA memory in deferred I/O areas enables memory corruption or information leaks on systems still using legacy fbdev consoles.[34] This lack of protection also contributes to poor multi-user support, as concurrent access from multiple sessions risks data races or privilege escalations without modern isolation like that provided by containerized environments.[16] As of 2025, fbdev faces ongoing maintenance challenges, with the subsystem deprecated for over a decade and no new drivers developed for emerging hardware, forcing reliance on software rendering fallbacks or VESA emulation for unsupported GPUs.[35] This stagnation is evident in the retirement of specific drivers, such as IntelFB in 2024, and continued emphasis in kernel updates to migrate away from fbdev toward DRM-based alternatives, leaving legacy setups vulnerable to unpatched issues on newer platforms.[36][35]Alternatives and Future Role

The primary alternative to the Linux framebuffer device (fbdev) is the Direct Rendering Manager (DRM) subsystem combined with Kernel Mode Setting (KMS), which was introduced in Linux kernel 2.6.28 in 2008 as part of efforts to modernize graphics handling.[37] DRM/KMS enables kernel-level control over display modes and provides a foundation for hardware-accelerated graphics rendering, supporting compositors in environments like Wayland and X11 by allowing direct GPU access without relying on legacy user-space mode setting. This shift addresses fbdev's limitations in acceleration by integrating with modern drivers for Intel, AMD, and NVIDIA hardware, offering better performance and security through modesetting in kernel space rather than user space.[17] Other alternatives include userspace renderers such as Mesa, which provides software-based implementations of OpenGL and Vulkan APIs, suitable for systems without dedicated GPU acceleration. In embedded contexts, direct GPU access via Vulkan can bypass traditional framebuffers entirely, leveraging Mesa's RADV or ANV drivers for efficient rendering on resource-constrained devices like ARM-based systems. As of 2025, fbdev remains retained in the Linux kernel for specific use cases, including boot-time graphics, recovery modes, and ultra-lightweight systems where minimal overhead is critical, such as in embedded or legacy hardware environments.[16] However, major distributions like Fedora and Ubuntu are gradually phasing it out in favor of DRM/KMS, with Fedora explicitly replacing fbdev drivers since version 36 in 2022 and no longer maintaining new fbdev implementations.[35] This deprecation reflects a broader industry push to consolidate on DRM for future-proofing, though fbdev emulation via DRM (simpledrm) ensures backward compatibility during transitions. For systems migrating from fbdev to KMS, administrators can enable the transition by appending themodeset=1 kernel parameter (e.g., i915.modeset=1 for Intel or nvidia-drm.modeset=1 for NVIDIA), which activates KMS alongside fbdev without immediate disruption, allowing gradual adoption of accelerated graphics.[38] This parameter forces kernel-space modesetting, bridging the gap until full DRM integration is complete.