Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Power chord

View on Wikipedia| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| perfect fifth | |

| root | |

| Tuning | |

| 2:3:4 |

A power chord ⓘ, also called a fifth chord, is a colloquial name for a chord on guitar, especially on electric guitar, that consists of the root note and the fifth, as well as possibly octaves of those notes. Power chords are commonly played with an amp with intentionally added distortion or overdrive effects. Power chords are a key element of many styles of rock,[1] especially heavy metal and punk rock.

Analysis

[edit]When two or more notes are played through a distortion process that non-linearly transforms the audio signal, additional partials are generated at the sums and differences of the frequencies of the harmonics of those notes (intermodulation distortion).[2] When a typical chord containing such intervals (for example, a major or minor chord) is played through distortion, the number of different frequencies generated, and the complex ratios between them, can make the resulting sound messy and indistinct.[3] This effect is accentuated as most guitars are tuned based on equal temperament, with the result that minor thirds are narrower, and major thirds wider, than they would be in just intonation.

However, in a power chord, the ratio between the frequencies of the root and fifth are very close to the just interval 3:2. When played through distortion, the intermodulation leads to the production of partials closely related in frequency to the harmonics of the original two notes, producing a more coherent sound. The intermodulation makes the spectrum of the sound expand in both directions, and with enough distortion, a new fundamental frequency component appears an octave lower than the root note of the chord played without distortion, giving a richer, more bassy and more subjectively "powerful" sound than the undistorted signal.[4] Even when played without distortion, the simple ratios between the harmonics in the notes of a power chord can give a stark and powerful sound, owing to the resultant tone (combination tone) effect. Power chords also have the advantage of being relatively easy to play , allowing fast chord changes and easy incorporation into melodies and riffs.

Terminology

[edit]

Theorists are divided on whether a power chord can be considered a chord in the traditional sense, with some requiring a "chord" to contain a minimum of three degrees of the scale. When the same interval is found in traditional and classical music, it would not usually be called a "chord", and may be considered a dyad (separated by an interval). However, the term is accepted as a pop and rock music term, most strongly associated with the overdriven electric guitar styles of hard rock, heavy metal, punk rock, and similar genres. The use of the term "power chord" has, to some extent, spilled over into the vocabulary of other instrumentalists, such as keyboard and synthesizer players.

Power chords are most commonly notated 5 or (no 3). For example, "C5" or "C(no 3)" refer to playing the root (C) and fifth (G). These can be inverted, so that the G is played below the C (making an interval of a fourth). They can also be played with octave doublings of the root or fifth note, which makes a sound that is subjectively higher pitched with less power in the low frequencies, but still retains the character of a power chord.

Another notation is ind, designating the chord as "indeterminate".[5] This refers to the fact that a power chord is neither major nor minor, as there is no third present. This gives the power chord a chameleon-like property; if played where a major chord might be expected, it can sound like a major chord, but when played where a minor chord might be expected, it can sound minor.

History

[edit]The first written instance of a power chord for guitar in the 20th century is to be found in the "Preludes" of Heitor Villa-Lobos, a Brazilian composer of the early twentieth century. Although classical guitar composer Francisco Tárrega used it before him, modern musicians use Villa-Lobos's version to this day. Power chords' use in rock music can be traced back to commercial recordings in the 1950s. Robert Palmer pointed to electric blues guitarists Willie Johnson and Pat Hare, both of whom played for Sun Records in the early 1950s, as the true originators of the power chord, citing as evidence Johnson's playing on Howlin' Wolf's "How Many More Years" (recorded 1951) and Hare's playing on James Cotton's "Cotton Crop Blues" (recorded 1954).[6] Scotty Moore opened Elvis Presley's 1957 hit "Jailhouse Rock" with power chords.[7] The "power chord" as known to modern electric guitarists was popularized first by Link Wray, who built on the distorted electric guitar sound of early records and by tearing the speaker cone in his 1958 instrumental "Rumble."

A later hit song built around power chords was "You Really Got Me" by the Kinks, released in 1964.[8] This song's riffs exhibit fast power-chord changes. The Who's guitarist, Pete Townshend, performed power chords with a theatrical windmill-strum,[9][10] for example in "My Generation".[11] On King Crimson's Red album, Robert Fripp thrashed with power chords.[12] Power chords are important in many forms of punk rock music, popularized in the genre by Ramones guitarist Johnny Ramone. Many punk guitarists used only power chords in their songs, most notably Billie Joe Armstrong and Doyle Wolfgang von Frankenstein.

Techniques

[edit]Power chords are often performed within a single octave, as this results in the closest matching of overtones. Octave doubling is sometimes done in power chords. Power chords are often pitched in a middle register.

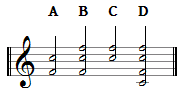

Shown above are four examples of an F5 chord. The letter names above the chords only indicate which different voicing is being used, and should not be conflated with the chord names typically used in popular music (e.g., C Major, B minor, etc.) A common voicing is the 1–5 perfect fifth (A), to which the octave can be added, 1-5-1 (B). A perfect fourth 5-1 (C) is also a power chord, as it implies the "missing" lower 1 pitch. Either or both of the pitches may be doubled an octave above or below (D is 5-1-5-1), which leads to another common variation, 5-1-5 (not shown).

Spider chords

[edit]

The spider chord is a guitar technique popularized during the 1980s thrash metal scene. Regarded as being popularized and named by Dave Mustaine of Megadeth, it is used to reduce string noise when playing (mostly chromatic) riffs that require chords across several strings. The chord or technique is used in the songs "Wake Up Dead", "Holy Wars...The Punishment Due", and "Ride the Lightning".[13]

D5 Bb5

e|-------|

B|-------|

G|-------|

D|-7-----|

A|-5--8--|

E|----6--|

3 <

1 4 <--Spider chord fingering

2 <

As seen in the above tab, the two power chords may be played in succession without shifting, making it easier and quicker,[13] and thus avoiding string noise. The normal fingering would be for both chords, requiring a simultaneous shift and string change. Note that the two power chords are a major third apart: if the first chord is the tonic the second is the minor submediant. The spider chord fingering also allows access to a major seventh chord without the third:[13]

AM7

e|------|

B|------|

G|------|

D|--6---|

A|--7---|

E|--5---|

3

4

2

The spider chord requires the player to use all four fingers of the fretting hand, thus its name. This technique then allows one to run down the neck playing either of the two chords.[13]

Fingering

[edit]Perhaps the most common implementation is 1-5-1', that is, the root note, a note a fifth above the root, and a note an octave above the root. When the strings are a fourth apart, especially the lower four strings in standard tuning, the lowest note is played with some fret on some string and the higher two notes are two frets higher on the next two strings. Using standard tuning, notes on the first or second string must be played one fret higher than this. (A bare fifth without octave doubling is the same, except that the highest of the three strings, in brackets below, is not played. A bare fifth with the bass note on the second string has the same fingering as one on the fifth or sixth string.)

G5 A5 D5 E5 G5 A5 D5 A5 E||----------------------------------------------(10)---(5)----| B||--------------------------------(8)----(10)----10-----5-----| G||------------------(7)----(9)-----7------9------7------2-----| D||----(5)----(7)-----7------9------5------7-------------------| A||-----5------7------5------7---------------------------------| E||-----3------5-----------------------------------------------|

An inverted barre fifth, i.e. a barre fourth, can be played with one finger, as in the example below, from the riff in "Smoke on the Water" by Deep Purple:

G5/D Bb5/F C5/G G5/D Bb5/F Db5/Ab C5/G E||------------------------|----------------------| B||------------------------|----------------------| G||*-----3-—5--------------|-----3-—6---5---------| D||*--5—-3--5--------------|---5—3--6—--5---------| A||---5--------------------|---5------------------| E||------------------------|----------------------|

|-----------------------|---------------------|| |-----------------------|---------------------|| |------3—-5--3—--0------|--------------------*|| |---5—-3--5-—3---0------|--------------------*|| |---5-------------------|---------------------|| |-----------------------|---------------------||

Another implementation used is 5-1'-5', that is, a note a fourth below the root, the root note, and a note a fifth above the root. (This is sometimes called a "fourth chord", but usually the second note is taken as the root, although it's not the lowest one.) When the strings are a fourth apart, the lower two notes are played with some fret on some two strings and the highest note is two frets higher on the next string. Of course, using standard tuning, notes on the first or second string must be played one fret higher.

D5 E5 G5 A5 D5 A5 D5 G5 E||-----------------------------------------------5------10----| B||---------------------------------10-----5------3------8-----| G||-------------------7------9------7------2-----(2)----(7)----| D||-----7------9------5------7-----(7)----(2)------------------| A||-----5------7-----(5)----(7)--------------------------------| E||----(5)----(7)----------------------------------------------|

With the drop D tuning—or any other dropped tuning for that matter—power chords with the bass on the sixth string can be played with one finger, and D power chords can be played on three open strings.

D5 E5 E||---------------- B||---------------- G||---------------- D||--0-------2----- A||--0-------2----- D||--0-------2-----

Occasionally, open, "stacked" power chords with more than three notes are used in drop D.

E||--------------------------5--- B||--3-------5-------7-------3--- G||--2-------4-------6-------2--- D||--0-------2-------4-------0--- A||--0-------2-------4-------0--- D||--0-------2-------4-------0---

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Glossary of Guitar Terms" Archived 2007-11-15 at the Wayback Machine, Mel Bay Publications, Inc. "A chord consisting of the first (root), fifth and eighth degree (octave) of the scale. Power chords are typically used in playing rock music."

- ^ Doug Coulter (2000). Digital Audio Processing, p.293. ISBN 0-87930-566-5. "Any non-linearity produces harmonics as well as sum and difference frequencies between the original components."

- ^ "Distortion – The Physics of Heavy Metal" , BBC

- ^ Robert Walser (1993). Running with the Devil, p.43. ISBN 0-8195-6260-2.

- ^ a b Benjamin, et al. (2008). Techniques and Materials of Music, p.191. ISBN 0-495-50054-2.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (1992). "Church of the Sonic Guitar". In DeCurtis, Anthony (ed.). Present Tense: Rock & Roll and Culture. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. pp. 13–38. ISBN 0-8223-1265-4.

- ^ "4 Guitarists Who Changed Southern Music (Part 2): Scotty Moore". porterbriggs.com. 8 January 2018. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Walser, Robert (1993). Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8195-6260-2.

- ^ Denyer (1992, "The advanced guitarist; Power chords and fret tapping: Power chords", p. 156)

- ^ Denyer (1992, "The Guitar Innovators: Pete Townshend", pp. 22–23)

- ^ "The Who - My Generation - Video Dailymotion". Archived from the original on 2013-12-05. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ^ Tamm (2002, Chapter Twelve: Chapter Twelve: Objective Art; Fripp's musical legacy: Melody): Tamm, Eric (2003) [1990], Robert Fripp: From crimson king to crafty master (Progressive Ears ed.), Faber and Faber (1990), ISBN 0-571-16289-4, Zipped Microsoft Word Document, archived from the original on 21 March 2012, retrieved 25 March 2012

- ^ a b c d "Video Question: Spider Chords" Archived 2010-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, JamPlay.com.

References

[edit]- Denyer, Ralph (1992). "Playing the guitar, pp. 65–160, and The chord dictionary, pp. 225–249". The guitar handbook. Special contributors Isaac Guillory and Alastair M. Crawford; Foreword by Robert Fripp (Fully revised and updated ed.). London and Sydney: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-32750-X.

Further reading

[edit]- Crawshaw, Edith A. H. (1939). "What's Wrong with Consecutive Fifths?". The Musical Times, Vol. 80, No. 1154. (Apr., 1939), pp. 256–257. (subscription required)

External links

[edit]Power chord

View on GrokipediaOverview and Basics

Definition and Characteristics

A power chord is a musical chord consisting primarily of two notes: the root note and its perfect fifth, forming a dyad that provides a sense of harmonic foundation without specifying major or minor tonality. This structure is often expanded by including the octave of the root for greater fullness, resulting in a three-note voicing that enhances resonance, particularly in amplified settings. The simplicity of this interval pair—spanning seven semitones—allows for easy execution on instruments like the guitar, where it leverages open strings or movable shapes across the fretboard. Key characteristics of power chords include their minimal voicing, typically limited to two or three notes, which emphasizes raw power, aggression, and rhythmic drive over complex harmony. This design prioritizes simplicity and versatility, making them ideal for fast-paced playing and distortion-heavy amplification, where the absence of additional intervals prevents muddiness in the sound. On electric guitar, power chords are commonly distorted to amplify their punchy, overdriven tone, creating a thick, wall-of-sound effect that dominates rock and related genres. A classic example is the E5 power chord on guitar, formed by playing the open low E string (root) together with the open A string (perfect fifth), often adding the D string at the 2nd fret (octave) for depth;[10] this shape is movable up the neck to form other root-fifth pairs like A5 or D5. Unlike full triads, which include the third interval to define major or minor quality, power chords omit this note entirely, yielding an ambiguous, neutral sonority that can imply either mode depending on context. This omission distinguishes them from traditional chords, focusing instead on intervallic consonance and textural impact.Role in Music

Power chords form the rhythmic and riff-based backbone of rock, punk, metal, and hard rock genres, delivering a stripped-down harmonic foundation that emphasizes drive and intensity over complex voicings.[11][12] In these styles, they underpin driving rhythms and memorable hooks, allowing guitarists to prioritize texture and momentum in ensemble arrangements.[13] Their structural simplicity—root and perfect fifth—provides key advantages in band contexts, particularly under heavy distortion and amplification, where full triads can become sonically cluttered due to clashing overtones; power chords retain harmonic clarity and punch by avoiding the third interval.[14] This design also enables effortless transposition, as the uniform shape slides uniformly along the guitar neck to shift keys without altering fingering patterns.[15] Iconic examples illustrate their riff-building prowess, such as the opening sequence in Deep Purple's "Smoke on the Water," which cycles through G5, Bb5, C5, and D5 power chords to craft a gritty, anthemic groove that defines hard rock.[16][17] In songwriting, power chords support rapid, aggressive execution through quick shifts and downstroke strumming, fueling the high-energy tempos of punk and metal while their tonal neutrality fosters modal ambiguity, permitting fluid exploration of scales without locking into major or minor resolutions.[18][19][20]Theoretical Analysis

Harmonic Structure

A power chord consists of the root note (the fundamental pitch), the perfect fifth (seven semitones above the root), and optionally the octave (the root repeated at twelve semitones higher), forming a dyad or triad without additional intervals.[21][14] This minimal structure emphasizes harmonic stability through the consonant perfect fifth interval, which spans a ratio of 3:2 in just intonation and provides a strong sense of resolution to the root without introducing dissonance from other scale degrees.[22] The theoretical neutrality of the power chord arises from the deliberate omission of the major or minor third (four or three semitones above the root, respectively), which in full triads defines the chord's major or minor quality.[14] Without this third, the power chord remains ambiguous in tonality, evoking a raw, unresolved power that avoids the emotional specificity of triadic harmony while reinforcing the root's dominance.[22] This neutrality allows the power chord to function as a versatile harmonic anchor in progressions, implying the root's primacy without committing to a modal center. In relation to full triads, the power chord serves as an incomplete subset, retaining only the root and fifth (and optional octave) from either a major or minor triad while excising the third to streamline the harmony.[22] This reduction heightens the root's perceptual and structural dominance, making power chords particularly effective in root-motion progressions where bass lines or melodies supply contextual color.[14] Power chords are conventionally notated in lead sheets and chord charts using symbols like "G5," where the number 5 denotes the inclusion of only the fifth above the specified root (G), excluding the third.[22] In guitar tablature (TAB), which represents fret positions on strings, a standard G5 power chord—root on low E, fifth on A, and octave on D—is depicted as follows:e|-----------------|

B|-----------------|

G|-----------------|

D|-5---------------| (G [octave](/page/Octave))

A|-5---------------| (D fifth)

E|-3---------------| (G [root](/page/Root))

e|-----------------|

B|-----------------|

G|-----------------|

D|-5---------------| (G [octave](/page/Octave))

A|-5---------------| (D fifth)

E|-3---------------| (G [root](/page/Root))