Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ergonomics

View on Wikipedia

Ergonomics, also known as human factors or human factors engineering (HFE), is the application of psychological and physiological principles to the engineering and design of products, processes, and systems. Primary goals of human factors engineering are to reduce human error, increase productivity and system availability, and enhance safety, health and comfort with a specific focus on the interaction between the human and equipment.[1]

The field is a combination of numerous disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, engineering, biomechanics, industrial design, physiology, anthropometry, interaction design, visual design, user experience, and user interface design. Human factors research employs methods and approaches from these and other knowledge disciplines to study human behavior and generate data relevant to previously stated goals. In studying and sharing learning on the design of equipment, devices, and processes that fit the human body and its cognitive abilities, the two terms, "human factors" and "ergonomics", are essentially synonymous as to their referent and meaning in current literature.[2][3][4]

The International Ergonomics Association defines ergonomics or human factors as follows:[5]

Ergonomics (or human factors) is the scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of interactions among humans and other elements of a system, and the profession that applies theory, principles, data and methods to design to optimize human well-being and overall system performance.

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

Human factors engineering is relevant in the design of such things as safe furniture and easy-to-use interfaces to machines and equipment. Proper ergonomic design is necessary to prevent repetitive strain injuries and other musculoskeletal disorders, which can develop over time and can lead to long-term disability. Human factors and ergonomics are concerned with the "fit" between the user, equipment, and environment or "fitting a job to a person"[6] or "fitting the task to the man".[7] It accounts for the user's capabilities and limitations in seeking to ensure that tasks, functions, information, and the environment suit that user.

To assess the fit between a person and the technology being used, human factors specialists or ergonomists consider the job (activity) being performed and the demands on the user; the equipment used (its size, shape, and how appropriate it is for the task); and the information used (how it is presented, accessed, and modified). Ergonomics draws on many disciplines in its study of humans and their environments, including anthropometry, biomechanics, mechanical engineering, industrial engineering, industrial design, information design, kinesiology, physiology, cognitive psychology, industrial and organizational psychology, and space psychology.

Etymology

[edit]The term ergonomics (from the Greek ἔργον, meaning "work", and νόμος, meaning "natural law") first entered the modern lexicon when Polish scientist Wojciech Jastrzębowski used the word in his 1857 article Rys ergonomji czyli nauki o pracy, opartej na prawdach poczerpniętych z Nauki Przyrody (The Outline of Ergonomics; i.e. Science of Work, Based on the Truths Taken from the Natural Science).[8] The French scholar Jean-Gustave Courcelle-Seneuil, apparently without knowledge of Jastrzębowski's article, used the word with a slightly different meaning in 1858. The introduction of the term to the English lexicon is widely attributed to British psychologist Hywel Murrell, at the 1949 meeting at the UK's Admiralty, which led to the foundation of The Ergonomics Society. He used it to encompass the studies in which he had been engaged during and after World War II.[9]

The expression human factors is a predominantly North American[10] term which has been adopted to emphasize the application of the same methods to non-work-related situations. A "human factor" is a physical or cognitive property of an individual or social behavior specific to humans that may influence the functioning of technological systems. The terms "human factors" and "ergonomics" are essentially synonymous.[2]

Domains of specialization

[edit]According to the International Ergonomics Association, within the discipline of ergonomics there exist domains of specialization. These comprise three main fields of research: physical, cognitive, and organizational ergonomics.

There are many specializations within these broad categories. Specializations in the field of physical ergonomics may include visual ergonomics. Specializations within the field of cognitive ergonomics may include usability, human–computer interaction, and user experience engineering.

Some specializations may cut across these domains: Environmental ergonomics is concerned with human interaction with the environment as characterized by climate, temperature, pressure, vibration, light.[11] The emerging field of human factors in highway safety uses human factors principles to understand the actions and capabilities of road users—car and truck drivers, pedestrians, cyclists, etc.—and use this knowledge to design roads and streets to reduce traffic collisions. Driver error is listed as a contributing factor in 44% of fatal collisions in the United States, so a topic of particular interest is how road users gather and process information about the road and its environment, and how to assist them to make the appropriate decision.[12]

New terms are being generated all the time. For instance, "user trial engineer" may refer to a human factors engineering professional who specializes in user trials.[13] Although the names change, human factors professionals apply an understanding of human factors to the design of equipment, systems and working methods to improve comfort, health, safety, and productivity.

Physical ergonomics

[edit]

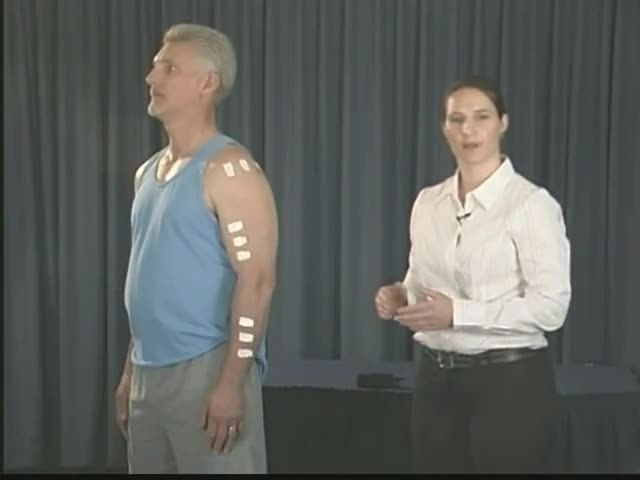

Physical ergonomics is concerned with human anatomy, and some of the anthropometric, physiological, and biomechanical characteristics as they relate to physical activity.[5] Physical ergonomic principles have been widely used in the design of both consumer and industrial products for optimizing performance and preventing/treating work-related disorders by reducing the mechanisms behind mechanically-induced acute and chronic musculoskeletal injuries/disorders.[14] Risk factors such as localized mechanical pressures, force and posture in a sedentary office environment lead to injuries attributed to an occupational environment.[15] Physical ergonomics is important to those diagnosed with physiological ailments or disorders such as arthritis (both chronic and temporary) or carpal tunnel syndrome. Pressure that is insignificant or imperceptible to those unaffected by these disorders may be very painful, or render a device unusable, for those who are. Many ergonomically designed products are also used or recommended to treat or prevent such disorders, and to treat pressure-related chronic pain.[16]

One of the most prevalent types of work-related injuries is musculoskeletal disorder. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMDs) result in persistent pain, loss of functional capacity and work disability, but their initial diagnosis is difficult because they are mainly based on complaints of pain and other symptoms.[17] Every year, 1.8 million U.S. workers experience WRMDs and nearly 600,000 of the injuries are serious enough to cause workers to miss work.[18] Certain jobs or work conditions cause a higher rate of worker complaints of undue strain, localized fatigue, discomfort, or pain that does not go away after overnight rest. These types of jobs are often those involving activities such as repetitive and forceful exertions; frequent, heavy, or overhead lifts; awkward work positions; or use of vibrating equipment.[19] The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has found substantial evidence that ergonomics programs can cut workers' compensation costs, increase productivity and decrease employee turnover.[20] Mitigation solutions can include both short term and long-term solutions. Short and long-term solutions involve awareness training, positioning of the body, furniture and equipment and ergonomic exercises. Sit-stand stations and computer accessories that provide soft surfaces for resting the palm as well as split keyboards are recommended. Additionally, resources within the HR department can be allocated to provide assessments to employees to ensure the above criteria are met.[21] Therefore, it is important to gather data to identify jobs or work conditions that are most problematic, using sources such as injury and illness logs, medical records, and job analyses.[19]

Innovative workstations that are being tested include sit-stand desks, height adjustable desk, treadmill desks, pedal devices and cycle ergometers.[22] In multiple studies these new workstations resulted in decreased waist circumference and improved psychological well-being. However a significant number of additional studies have seen no marked improvement in health outcomes.[23]

With the emergence of collaborative robots and smart systems in manufacturing environments, the artificial agents can be used to improve physical ergonomics of human co-workers. For example, during human–robot collaboration the robot can use biomechanical models of the human co-worker in order to adjust the working configuration and account for various ergonomic metrics, such as human posture, joint torques, arm manipulability and muscle fatigue.[24][25] The ergonomic suitability of the shared workspace with respect to these metrics can also be displayed to the human with workspace maps through visual interfaces.[26]

Cognitive ergonomics

[edit]Cognitive ergonomics is concerned with mental processes, such as perception, emotion, memory, reasoning, and motor response, as they affect interactions among humans and other elements of a system.[5][27] Relevant topics include mental workload, decision-making, skilled performance, human reliability, work stress and training as these may relate to human–system and human–computer interaction design.[23]

Organizational ergonomics and safety culture

[edit]Organizational ergonomics is concerned with the optimization of socio-technical systems, including their organizational structures, policies, and processes.[5] Relevant topics include human communication successes or failures in adaptation to other system elements,[28][29] crew resource management, work design, work systems, design of working times, teamwork, participatory ergonomics, community ergonomics, cooperative work, new work programs, virtual organizations, remote work, and quality management. Safety culture within an organization of engineers and technicians has been linked to engineering safety with cultural dimensions including power distance and ambiguity tolerance. Low power distance has been shown to be more conducive to a safety culture. Organizations with cultures of concealment or lack of empathy have been shown to have poor safety culture.

History

[edit]Ancient societies

[edit]Some have stated that human ergonomics began with Australopithecus prometheus (also known as "Little Foot"), a primate who created handheld tools out of different types of stone, clearly distinguishing between tools based on their ability to perform designated tasks.[30] The foundations of the science of ergonomics appear to have been laid within the context of the culture of Ancient Greece. A good deal of evidence indicates that Greek civilization in the 5th century BC used ergonomic principles in the design of their tools, jobs, and workplaces. One outstanding example of this can be found in the description Hippocrates gave of how a surgeon's workplace should be designed and how the tools he uses should be arranged.[31] The archaeological record also shows that the early Egyptian dynasties made tools and household equipment that illustrated ergonomic principles.

Industrial societies

[edit]Bernardino Ramazzini was one of the first people to systematically study the illness that resulted from work, earning himself the nickname "father of occupational medicine". In the late 1600s and early 1700s Ramazzini visited many worksites where he documented the movements of laborers and spoke to them about their ailments. He then published De Morbis Artificum Diatriba (Latin for "Diseases of Workers") which detailed occupations, common illnesses, and remedies.[32] In the 19th century, Frederick Winslow Taylor pioneered the "scientific management" method, which proposed a way to find the optimum method of carrying out a given task. Taylor found that he could, for example, triple the amount of coal that workers were shoveling by incrementally reducing the size and weight of coal shovels until the fastest shoveling rate was reached.[33] Frank and Lillian Gilbreth expanded Taylor's methods in the early 1900s to develop the "time and motion study". They aimed to improve efficiency by eliminating unnecessary steps and actions. By applying this approach, the Gilbreths reduced the number of motions in bricklaying from 18 to 4.5,[clarification needed] allowing bricklayers to increase their productivity from 120 to 350 bricks per hour.[33]

However, this approach was rejected by Russian researchers who focused on the well-being of the worker. At the First Conference on Scientific Organization of Labour (1921) Vladimir Bekhterev and Vladimir Nikolayevich Myasishchev criticised Taylorism. Bekhterev argued that "The ultimate ideal of the labour problem is not in it [Taylorism], but is in such organisation of the labour process that would yield a maximum of efficiency coupled with a minimum of health hazards, absence of fatigue and a guarantee of the sound health and all round personal development of the working people."[34] Myasishchev rejected Frederick Taylor's proposal to turn man into a machine. Dull monotonous work was a temporary necessity until a corresponding machine can be developed. He also went on to suggest a new discipline of "ergology" to study work as an integral part of the re-organisation of work. The concept was taken up by Myasishchev's mentor, Bekhterev, in his final report on the conference, merely changing the name to "ergonology"[34]

Aviation

[edit]Prior to World War I, the focus of aviation psychology was on the aviator himself, but the war shifted the focus onto the aircraft, in particular, the design of controls and displays, and the effects of altitude and environmental factors on the pilot. The war saw the emergence of aeromedical research and the need for testing and measurement methods. Studies on driver behavior started gaining momentum during this period, as Henry Ford started providing millions of Americans with automobiles. Another major development during this period was the performance of aeromedical research. By the end of World War I, two aeronautical labs were established, one at Brooks Air Force Base, Texas and the other at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base outside of Dayton, Ohio. Many tests were conducted to determine which characteristic differentiated the successful pilots from the unsuccessful ones. During the early 1930s, Edwin Link developed the first flight simulator. The trend continued and more sophisticated simulators and test equipment were developed. Another significant development was in the civilian sector, where the effects of illumination on worker productivity were examined. This led to the identification of the Hawthorne Effect, which suggested that motivational factors could significantly influence human performance.[33]

World War II marked the development of new and complex machines and weaponry, and these made new demands on operators' cognition. It was no longer possible to adopt the Tayloristic principle of matching individuals to preexisting jobs. Now the design of equipment had to take into account human limitations and take advantage of human capabilities. The decision-making, attention, situational awareness and hand-eye coordination of the machine's operator became key in the success or failure of a task. There was substantial research conducted to determine the human capabilities and limitations that had to be accomplished. A lot of this research took off where the aeromedical research between the wars had left off. An example of this is the study done by Fitts and Jones (1947), who studied the most effective configuration of control knobs to be used in aircraft cockpits.

Much of this research transcended into other equipment with the aim of making the controls and displays easier for the operators to use. The entry of the terms "human factors" and "ergonomics" into the modern lexicon date from this period. It was observed that fully functional aircraft flown by the best-trained pilots, still crashed. In 1943 Alphonse Chapanis, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, showed that this so-called "pilot error" could be greatly reduced when more logical and differentiable controls replaced confusing designs in airplane cockpits. After the war, the Army Air Force published 19 volumes summarizing what had been established from research during the war.[33]

In the decades since World War II, human factors has continued to flourish and diversify. Work by Elias Porter and others within the RAND Corporation after WWII extended the conception of human factors. "As the thinking progressed, a new concept developed—that it was possible to view an organization such as an air-defense, man-machine system as a single organism and that it was possible to study the behavior of such an organism. It was the climate for a breakthrough."[35] In the initial 20 years after the World War II, most activities were done by the "founding fathers": Alphonse Chapanis, Paul Fitts, and Small.[36]

Cold War

[edit]The beginning of the Cold War led to a major expansion of Defense supported research laboratories. Many labs established during WWII started expanding. Most of the research following the war was military-sponsored. Large sums of money were granted to universities to conduct research. The scope of the research also broadened from small equipments to entire workstations and systems. Concurrently, a lot of opportunities started opening up in the civilian industry. The focus shifted from research to participation through advice to engineers in the design of equipment. After 1965, the period saw a maturation of the discipline. The field has expanded with the development of the computer and computer applications.[33]

The Space Age created new human factors issues such as weightlessness and extreme g-forces. Tolerance of the harsh environment of space and its effects on the mind and body were widely studied.[37]

Information age

[edit]The dawn of the Information Age has resulted in the related field of human–computer interaction (HCI). Likewise, the growing demand for and competition among consumer goods and electronics has resulted in more companies and industries including human factors in their product design. Using advanced technologies in human kinetics, body-mapping, movement patterns and heat zones, companies are able to manufacture purpose-specific garments, including full body suits, jerseys, shorts, shoes, and even underwear.[citation needed]

Organizations

[edit]Formed in 1946 in the UK, the oldest professional body for human factors specialists and ergonomists is The Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors, formally known as the Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors and before that, The Ergonomics Society.

The Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (HFES) was founded in 1957. The Society's mission is to promote the discovery and exchange of knowledge concerning the characteristics of human beings that are applicable to the design of systems and devices of all kinds.

The Association of Canadian Ergonomists - l'Association canadienne d'ergonomie (ACE) was founded in 1968.[38] It was originally named the Human Factors Association of Canada (HFAC), with ACE (in French) added in 1984, and the consistent, bilingual title adopted in 1999. According to its 2017 mission statement, ACE unites and advances the knowledge and skills of ergonomics and human factors practitioners to optimise human and organisational well-being.[39]

The International Ergonomics Association (IEA) is a federation of ergonomics and human factors societies from around the world. The mission of the IEA is to elaborate and advance ergonomics science and practice, and to improve the quality of life by expanding its scope of application and contribution to society. As of September 2008, the International Ergonomics Association has 46 federated societies and 2 affiliated societies.

The Human Factors Transforming Healthcare (HFTH) is an international network of HF practitioners who are embedded within hospitals and health systems. The goal of the network is to provide resources for human factors practitioners and healthcare organizations looking to successfully apply HF principles to improve patient care and provider performance. The network also serves as collaborative platform for human factors practitioners, students, faculty, industry partners, and those curious about human factors in healthcare.[40]

Related organizations

[edit]The Institute of Occupational Medicine (IOM) was founded by the coal industry in 1969. From the outset the IOM employed an ergonomics staff to apply ergonomics principles to the design of mining machinery and environments. To this day, the IOM continues ergonomics activities, especially in the fields of musculoskeletal disorders, heat stress, and the ergonomics of personal protective equipment (PPE). Like many in occupational ergonomics, the demands and requirements of an ageing UK workforce are a growing concern and interest to IOM ergonomists.

The International Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) is a professional organization for mobility engineering professionals in the aerospace, automotive, and commercial vehicle industries. The Society is a standards development organization for the engineering of powered vehicles of all kinds, including cars, trucks, boats, aircraft, and others. The Society of Automotive Engineers has established a number of standards used in the automotive industry and elsewhere. It encourages the design of vehicles in accordance with established human factors principles. It is one of the most influential organizations with respect to ergonomics work in automotive design. This society regularly holds conferences which address topics spanning all aspects of human factors and ergonomics.[41]

Practitioners

[edit]Human factors practitioners come from a variety of backgrounds, though predominantly they are psychologists (from the various subfields of industrial and organizational psychology, engineering psychology, cognitive psychology, perceptual psychology, applied psychology, and experimental psychology) and physiologists. Designers (industrial, interaction, and graphic), anthropologists, technical communication scholars and computer scientists also contribute. Typically, an ergonomist will have an undergraduate degree in psychology, engineering, design or health sciences, and usually a master's degree or doctoral degree in a related discipline. Though some practitioners enter the field of human factors from other disciplines, both M.S. and PhD degrees in Human Factors Engineering are available from several universities worldwide.

Sedentary workplace

[edit]Contemporary offices did not exist until the 1830s,[42] with Wojciech Jastrzębowski's seminal book on MSDergonomics following in 1857[43] and the first published study of posture appearing in 1955.[44]

As the American workforce began to shift towards sedentary employment, the prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders, cognitive issues, etc. began to rise. In 1900, 41% of the US workforce was employed in agriculture but by 2000 that had dropped to 1.9%.[45] This coincides with an increase in growth in desk-based employment (25% of all employment in 2000)[46] and the surveillance of non-fatal workplace injuries by OSHA and Bureau of Labor Statistics in 1971.[47] Sedentary behavior requires a basal metabolic rate of 1.0–1.5 and occurs in a sitting or reclining position. Adults older than 50 years report spending more time sedentary and for adults older than 65 years this is often 80% of their awake time. Multiple studies show a dose-response relationship between sedentary time and all-cause mortality with an increase of 3% mortality per additional sedentary hour each day.[48] High quantities of sedentary time without breaks is correlated to higher risk of chronic disease, obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer.[23]

Currently, there is a large proportion of the overall workforce who is employed in low physical activity occupations.[49] Sedentary behavior, such as spending long periods of time in seated positions poses a serious threat for injuries and additional health risks.[50] Unfortunately, even though some workplaces make an effort to provide a well designed environment for sedentary employees, any employee who is performing large amounts of sitting will likely experience discomfort.[50] There are existing conditions that would predispose both individuals and populations to an increase in prevalence of living sedentary lifestyles, including: socioeconomic determinants, education levels, occupation, living environment, age (as mentioned above) and more.[51] A study published by the Iranian Journal of Public Health examined socioeconomic factors and sedentary lifestyle effects for individuals in a working community. The study concluded that individuals who reported living in low income environments were more inclined to living sedentary behavior compared to those who reported being of high socioeconomic status.[51] Individuals who achieve less education are also considered to be a high risk group to partake in sedentary lifestyles, however, each community is different and has different resources available that may vary this risk.[51] Oftentimes, larger worksites are associated with increased occupational sitting. Those who work in environments that are classified as business and office jobs are typically more exposed to sitting and sedentary behavior while in the workplace. Additionally, occupations that are full-time, have schedule flexibility, are also included in that demographic, and are more likely to sit often throughout their workday.[52]

Policy implementation

[edit]Obstacles surrounding better ergonomic features to sedentary employees include cost, time, effort and for both companies and employees. The evidence above helps establish the importance of ergonomics in a sedentary workplace, yet missing information from this problem is enforcement and policy implementation. As a modernized workplace becomes more technology-based, more jobs are becoming primarily seated, leading to a need to prevent chronic injuries and pain. This is becoming easier with the amount of research around ergonomic tools saving companies money by limiting the number of days missed from work and workers' compensation cases.[53] The way to ensure that corporations prioritize these health outcomes for their employees is through policy and implementation.[53]

In the United States, there are no nationwide policies that are currently in place; however, a handful of big companies and states have taken on cultural policies to ensure the safety of all workers. For example, the state of Nevada risk management department has established a set of ground rules for both agencies' responsibilities and employees' responsibilities.[54] The agency responsibilities include evaluating workstations, using risk management resources when necessary and keeping OSHA records.[54]

Methods

[edit]Until recently, methods used to evaluate human factors and ergonomics ranged from simple questionnaires to more complex and expensive usability labs.[55] Some of the more common human factors methods are listed below:

- Ethnographic analysis: Using methods derived from ethnography, this process focuses on observing the uses of technology in a practical environment. It is a qualitative and observational method that focuses on "real-world" experience and pressures, and the usage of technology or environments in the workplace. The process is best used early in the design process.[56]

- Focus groups are another form of qualitative research in which one individual will facilitate discussion and elicit opinions about the technology or process under investigation. This can be on a one-to-one interview basis, or in a group session. Can be used to gain a large quantity of deep qualitative data,[57] though due to the small sample size, can be subject to a higher degree of individual bias.[58] Can be used at any point in the design process, as it is largely dependent on the exact questions to be pursued, and the structure of the group. Can be extremely costly.

- Iterative design: Also known as prototyping, the iterative design process seeks to involve users at several stages of design, to correct problems as they emerge. As prototypes emerge from the design process, these are subjected to other forms of analysis as outlined in this article, and the results are then taken and incorporated into the new design. Trends among users are analyzed, and products redesigned. This can become a costly process, and needs to be done as soon as possible in the design process before designs become too concrete.[56]

- Meta-analysis: A supplementary technique used to examine a wide body of already existing data or literature to derive trends or form hypotheses to aid design decisions. As part of a literature survey, a meta-analysis can be performed to discern a collective trend from individual variables.[58]

- Subjects-in-tandem: Two subjects are asked to work concurrently on a series of tasks while vocalizing their analytical observations. The technique is also known as "Co-Discovery" as participants tend to feed off of each other's comments to generate a richer set of observations than is often possible with the participants separately. This is observed by the researcher, and can be used to discover usability difficulties. This process is usually recorded.[citation needed]

- Surveys and questionnaires: A commonly used technique outside of human factors as well, surveys and questionnaires have an advantage in that they can be administered to a large group of people for relatively low cost, enabling the researcher to gain a large amount of data. The validity of the data obtained is, however, always in question, as the questions must be written and interpreted correctly, and are, by definition, subjective. Those who actually respond are in effect self-selecting as well, widening the gap between the sample and the population further.[58]

- Task analysis: A process with roots in activity theory, task analysis is a way of systematically describing human interaction with a system or process to understand how to match the demands of the system or process to human capabilities. The complexity of this process is generally proportional to the complexity of the task being analyzed, and so can vary in cost and time involvement. It is a qualitative and observational process. Best used early in the design process.[58]

- Human performance modeling: A method of quantifying human behavior, cognition, and processes; a tool used by human factors researchers and practitioners for both the analysis of human function and for the development of systems designed for optimal user experience and interaction.[59]

- Think aloud protocol: Also known as "concurrent verbal protocol", this is the process of asking a user to execute a series of tasks or use technology, while continuously verbalizing their thoughts so that a researcher can gain insights as to the users' analytical process. Can be useful for finding design flaws that do not affect task performance, but may have a negative cognitive effect on the user. Also useful for utilizing experts to better understand procedural knowledge of the task in question. Less expensive than focus groups, but tends to be more specific and subjective.[60]

- User analysis: This process is based around designing for the attributes of the intended user or operator, establishing the characteristics that define them, creating a persona for the user.[61] Best done at the outset of the design process, a user analysis will attempt to predict the most common users, and the characteristics that they would be assumed to have in common. This can be problematic if the design concept does not match the actual user, or if the identified are too vague to make clear design decisions from. This process is, however, usually quite inexpensive, and commonly used.[58]

- "Wizard of Oz": This is a comparatively uncommon technique but has seen some use in mobile devices. Based upon the Wizard of Oz experiment, this technique involves an operator who remotely controls the operation of a device to imitate the response of an actual computer program. It has the advantage of producing a highly changeable set of reactions, but can be quite costly and difficult to undertake.

- Methods analysis is the process of studying the tasks a worker completes using a step-by-step investigation. Each task in broken down into smaller steps until each motion the worker performs is described. Doing so enables you to see exactly where repetitive or straining tasks occur.

- Time studies determine the time required for a worker to complete each task. Time studies are often used to analyze cyclical jobs. They are considered "event based" studies because time measurements are triggered by the occurrence of predetermined events.[62]

- Work sampling is a method in which the job is sampled at random intervals to determine the proportion of total time spent on a particular task.[62] It provides insight into how often workers are performing tasks which might cause strain on their bodies.

- Predetermined time systems are methods for analyzing the time spent by workers on a particular task. One of the most widely used predetermined time system is called Methods-Time-Measurement. Other common work measurement systems include MODAPTS and MOST.[clarification needed] Industry specific applications based on PTS are Seweasy, MODAPTS and GSD.[63]

- Cognitive walkthrough: This method is a usability inspection method in which the evaluators can apply user perspective to task scenarios to identify design problems. As applied to macroergonomics, evaluators are able to analyze the usability of work system designs to identify how well a work system is organized and how well the workflow is integrated.[64]

- Kansei method: This is a method that transforms consumer's responses to new products into design specifications. As applied to macroergonomics, this method can translate employee's responses to changes to a work system into design specifications.[64]

- High Integration of Technology, Organization, and People: This is a manual procedure done step-by-step to apply technological change to the workplace. It allows managers to be more aware of the human and organizational aspects of their technology plans, allowing them to efficiently integrate technology in these contexts.[64]

- Top modeler: This model helps manufacturing companies identify the organizational changes needed when new technologies are being considered for their process.[64]

- Computer-integrated Manufacturing, Organization, and People System Design: This model allows for evaluating computer-integrated manufacturing, organization, and people system design based on knowledge of the system.[64]

- Anthropotechnology: This method considers analysis and design modification of systems for the efficient transfer of technology from one culture to another.[64]

- Systems analysis tool: This is a method to conduct systematic trade-off evaluations of work-system intervention alternatives.[64]

- Macroergonomic analysis of structure: This method analyzes the structure of work systems according to their compatibility with unique sociotechnical aspects.[64]

- Macroergonomic analysis and design: This method assesses work-system processes by using a ten-step process.[64]

- Virtual manufacturing and response surface methodology: This method uses computerized tools and statistical analysis for workstation design.[65]

- Computer-aided ergonomics':' This method uses computers to solve complex ergonomic problems

Weaknesses

[edit]Problems related to measures of usability include the fact that measures of learning and retention of how to use an interface are rarely employed and some studies treat measures of how users interact with interfaces as synonymous with quality-in-use, despite an unclear relation.[66]

Although field methods can be extremely useful because they are conducted in the users' natural environment, they have some major limitations to consider. The limitations include:

- Usually take more time and resources than other methods

- Very high effort in planning, recruiting, and executing compared with other methods

- Much longer study periods and therefore requires much goodwill among the participants

- Studies are longitudinal in nature, therefore, attrition can become a problem.[67]

See also

[edit]- Canadian Society for Biomechanics

- ISO 9241

- Journal of Occupational Health Psychology

- Right to sit

- Right to sit in the United States

- Wojciech Jastrzębowski (1799–1882), a Polish pioneer of ergonomics

References

[edit]- ^ Wickens; Gordon; Liu (1997). An Introduction to Human Factors Engineering (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2018.

- ^ a b ISO 6385 defines "ergonomics" and the "study of human factors" similarly, as the "scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of interactions among humans and other elements of a system, and the profession that applies theory, principles and methods to design to optimize overall human performance."

- ^ "What is ergonomics?". Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors. 9 September 2023. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

Essentially yes, they are different terms with the same meaning but one term may be more in favour in one country or in one industry than another. They can be used interchangeably.

- ^ "CRIOP" (PDF). SINTEF.

Ergonomics is a scientific discipline that applies systematic methods and knowledge about people to evaluate and approve the interaction between individuals, technology and organisation. The aim is to create a working environment and the tools in them for maximum work efficiency and maximum worker health and safety ... Human factors is a scientific discipline that applies systematic methods and knowledge about people to evaluate and improve the interaction between individuals, technology and organisations. The aim is to create a working environment (that to the largest extent possible) contributes to achieving healthy, effective and safe operations.

- ^ a b c d International Ergonomics Association. Human Factors/Ergonomics (HF/E). Website. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Safety and Health Topics | Ergonomics | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Grandjean, E. (1980) Fitting the Task to the Man: An Ergonomic Approach. Taylor & Francis; 3rd Edition.

- ^ "Wojciech Jastrzębowski". Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Hywel Murrell

- ^ Swain, A.D.; Guttmann, H.E. (1983). "Handbook of Human Reliability Analysis with Emphasis on Nuclear Power Plant Applications. NUREG/CR-1278" (PDF). USNRC.

Human Factors Engineering, Human Engineering, Human Factors, and Ergonomics ... describe a discipline concerned with designing machines, operations, and work environments so that they match human capacities and limitations ... The first three terms are used most widely in the United States ... The last term, ergonomics, is used most frequently in other countries but is now becoming popular in the United States as well.

- ^ "Home Page of Environmental Ergonomics Society". Environmental-ergonomics.org. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ John L. Campbell; Monica G. Lichty; et al. (2012). National Cooperative Highway Research Project Report 600: Human Factors Guidelines for Road Systems (Second ed.). Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

- ^ "Human Factors Engineering Professional Education University of Michigan". nexus.engin.umich.edu. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Madeleine, P., Vangsgaard, S., de Zee, M., Kristiansen, M. V., Verma, R., Kersting, U. G., Villumsen, M., & Samani, A. (2014). Ergonomics in sports and at work. In Proceedings, 11th International Symposium on Human Factors in Organisational Design and Management, ODAM, & 46th Annual Nordic Ergonomics Society Conference, NES, 17–20 August 2014, Copenhagen, Denmark (pp. 57–62). International Ergonomics Association.

- ^ "Ergonomic Guidelines for Common Job Functions Within The Telecommunication Industry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2023.

- ^ Kaplan, Sally. "6 affordable products that have helped me deal with back pain and muscle tension". Insider. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Isabel A P.; Oishi, Jorge; Coury, Helenice J C Gil (2008). "Clinical and functional aspects of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among active workers". Revista de Saúde Pública. 42 (1): 108–116. doi:10.1590/s0034-89102008000100014. PMID 18200347.

- ^ Charles N. Jeffress (27 October 2000). "BEACON Biodynamics and Ergonomics Symposium". University of Connecticut, Farmington, Conn.

- ^ a b "Workplace Ergonomics: NIOSH Provides Steps to Minimize Musculoskeletal Disorders". 2003. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ Jeffress, Charles N. (27 October 2000). BEACON Biodynamics and Ergonomics Symposium. Farmington, Connecticut: University of Connecticut.

- ^ "Ergonomic Guidelines for Common Job Functions Within The Telecommunication Industry" (PDF).

- ^ "What Is Ergonomics and Its Application in The Real World". spassway. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Neuhaus, M.; Eakin, E. G.; Straker, L.; Owen, N.; Dunstan, D. W.; Reid, N.; Healy, G. N. (October 2014). "Reducing occupational sedentary time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence on activity-permissive workstations" (PDF). Obesity Reviews. 15 (10): 822–838. doi:10.1111/obr.12201. ISSN 1467-789X. PMID 25040784. S2CID 9092084.

- ^ Peternel, Luka; Fang, Cheng; Tsagarakis, Nikos; Ajoudani, Arash (2019). "A selective muscle fatigue management approach to ergonomic human–robot co-manipulation". Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing. 58. Elsevier: 69–79. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2019.01.013.

- ^ Kim, Wansoo; Peternel, Luka; Lorenzini, Marta; Babič, Jan; Ajoudani, Arash (2021). "A Human–Robot Collaboration Framework for Improving Ergonomics During Dexterous Operation of Power Tools". Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing. 68 102084. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2020.102084. ISSN 0736-5845.

- ^ Peternel, Luka; Schøn, Daniel Tofte; Fang, Cheng (2021). "Binary and Hybrid Work-Condition Maps for Interactive Exploration of Ergonomic Human Arm Postures". Frontiers in Neurorobotics. 14. Frontiers: 114. doi:10.3389/fnbot.2020.590241. PMC 7819876. PMID 33488376.

- ^ H. Diamantopoulos and W. Wang, "Accommodating and Assisting Human Partners in Human–Robot Collaborative Tasks through Emotion Understanding," in 2021 International Conference on Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (ICMAE), 2021: IEEE, pp. 523–528.

- ^ Huang, H. (2015). Development of New Methods to Support Systemic Incident Analysis (Doctoral dissertation, Queen Mary University of London).

- ^ Hollnagel, E. (2018). Safety–I and safety–II: the past and future of safety management. CRC press.

- ^ Dart, R. A. (1960). "The Bone Tool-Manufacturing Ability of Australopithecus Prometheus". American Anthropologist. 62 (1): 134–138. doi:10.1525/aa.1960.62.1.02a00080.

- ^ Marmaras, N.; Poulakakis, G.; Papakostopoulos, V. (August 1999). "Ergonomic design in ancient Greece". Applied Ergonomics. 30 (4): 361–368. doi:10.1016/S0003-6870(98)00050-7. PMID 10416849.

- ^ Franco, Giuliano; Franco, Francesca (2001). "Bernardino Ramazzini: The Father of Occupational Medicine". American Journal of Public Health. 91 (9): 1382. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.9.1382. PMC 1446786. PMID 11527763.

- ^ a b c d e Nikolayevich Myasishchev estia.com/library/1358216/the-history-of-human-factors-and-ergonomics The History of Human Factors and Ergonomics[permanent dead link], David Meister

- ^ a b Neville Moray (2005). Ergonomics: The history and scope of human factors. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32257-7. OCLC 54974550. OL 7491513M. 041532257X.

- ^ Porter, Elias H. (1964). Manpower Development: The System Training Concept. New York: Harper and Row, p. xiii.

- ^ "WHAT DOES HUMAN FACTORS MEAN?". www.linkedin.com. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "NASA-STD-3000".

1.2 OVERVIEW.

- ^ "Association of Canadian Ergonomists - about us". Association of Canadian Ergonomists. 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Mission". Association of Canadian Ergonomists. 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "About HFTH | About Human Factors Transforming Healthcare".

- ^ "Learning Center - Human Factors and Ergonomics - SAE MOBILUS". saemobilus.sae.org. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Smithsonian Education. Carbon to Computers. (1998) A Short History of the Birth and Growth of the American Office. http://www.smithsonianeducation.org/scitech/carbons/text/birth.html

- ^ Jastrzębowski, W. B., Koradecka, D., (2000) An outline of ergonomics, or the science of work based upon the truths drawn from the Science of Nature: 1857 International Ergonomics Association., & Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. (2000).. Warsaw: Central Institute for Labour Protection.

- ^ Hewes, G (1955). "World Distribution of Certain Postural Habits". American Anthropologist. 57 (2): 231–244. doi:10.1525/aa.1955.57.2.02a00040. JSTOR 666393.

- ^ C. Dimitri, A. Effland, and N. Conklin, (2005) The 20th Century Transformation of U.S. Agriculture and Farm Policy, Economic Information Bulletin Number

- ^ Wyatt, I. D. (2006). "Occupational changes during the 20th century". Monthly Lab. Rev. 129: 35.

- ^ Roughton, James E. (2003). "Occupational Injury and Illness Recording and Reporting Requirements, Part 1904". OSHA 2002 Recordkeeping Simplified. Elsevier. pp. 48–147. doi:10.1016/b978-075067559-8/50029-6. ISBN 978-0-7506-7559-8.

- ^ de Rezende, Leandro Fornias Machado; Rey-López, Juan Pablo; Matsudo, Victor Keihan Rodrigues; do Carmo Luiz, Olinda (9 April 2014). "Sedentary behavior and health outcomes among older adults: a systematic review". BMC Public Health. 14: 333. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-333. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 4021060. PMID 24712381.

- ^ Parry, Sharon; Straker, Leon (2013). "The contribution of office work to sedentary behaviour associated risk". BMC Public Health. 13: 296. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-296. PMC 3651291. PMID 23557495.

- ^ a b Canadian Centre for Occupational Health. (2019, March 15). (none). Retrieved February, 2019, from https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/ergonomics/sitting/sitting_overview.html

- ^ a b c Konevic, S.; Martinovic, J.; Djonovic, N. (2015). "Association of Socioeconomic Factors and Sedentary Lifestyle in Belgrade's Suburb, Working Class Community". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 44 (8): 1053–60. PMC 4645725. PMID 26587469.

- ^ Yang, Lin; Hipp, J. Aaron; Lee, Jung Ae; Tabak, Rachel G.; Dodson, Elizabeth A.; Marx, Christine M.; Brownson, Ross C. (2017). "Work-related correlates of occupational sitting in a diverse sample of employees in Midwest metropolitan cities". Preventive Medicine Reports. 6: 197–202. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.03.008. PMC 5374873. PMID 28373929.

- ^ a b Polanyi, M. F.; Cole, D. C.; Ferrier, S. E.; Facey, M.; Worksite Upper Extremity Research Group (March 2005). "Paddling upstream: A contextual analysis of implementation of a workplace ergonomic policy at a large newspaper". Applied Ergonomics. 36 (2): 231–239. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2004.10.011. PMID 15694078.

- ^ a b "Ergonomics Policy". risk.nv.gov. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Stanton, N.; Salmon, P.; Walker G.; Baber, C.; Jenkins, D. (2005). Human Factors Methods; A Practical Guide For Engineering and Design. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0-7546-4661-7.

- ^ a b Carrol, J.M. (1997). "Human-Computer Interaction: Psychology as a Science of Design". Annual Review of Psychology. 48: 61–83. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.24.5979. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.61. PMID 15012476.

- ^ "Survey Methods, Pros & Cons". Better Office.net. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Wickens, C.D.; Lee J.D.; Liu Y.; Gorden Becker S.E. (1997). An Introduction to Human Factors Engineering, 2nd Edition. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-321-01229-1.

- ^ Bruno, Fabio; Barbieri, Loris; Muzzupappa, Maurizio (2020). "A Mixed Reality system for the ergonomic assessment of industrial workstations". International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing. 14 (3): 805–812. doi:10.1007/s12008-020-00664-x. S2CID 225517293.

- ^ Kuusela, H.; Paul, P. (2000). "A comparison of concurrent and retrospective verbal protocol analysis". The American Journal of Psychology. 113 (3): 387–404. doi:10.2307/1423365. JSTOR 1423365. PMID 10997234.

- ^ Obinna P. Fidelis, Olusoji A. Adalumo, Ephraim O. Nwoye (2018). Ergonomic Suitability of Library Readers' Furniture in a Nigerian University; AJERD Vol 1, Issue 3,366-370

- ^ a b Thomas J. Armstrong (2007). Measurement and Design of Work.

- ^ Miller, Doug (2013). "Towards Sustainable Labour Costing in UK Fashion Retail". Social Science Research Network. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2212100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Brookhuis, K., Hedge, A., Hendrick, H., Salas, E., and Stanton, N. (2005). Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics Models. Florida: CRC Press.

- ^ Ben-Gal; et al. (2002). "The Ergonomic Design of Workstation Using Rapid Prototyping and Response Surface Methodology" (PDF). IIE Transactions on Design and Manufacturing. 34 (4): 375–391. doi:10.1080/07408170208928877. S2CID 214650306. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Hornbaek, K (2006). "Current Practice in Measuring Usability: Challenges to Usability Studies and Research". International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 64 (2): 79–102. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2005.06.002. S2CID 2615818.

- ^ Dumas, J. S.; Salzman, M. C. (2006). Reviews of Human Factors and Ergonomics. Vol. 2. Human Factors and Ergonomics Society.

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Thomas J. Armstrong (2008), Chapter 10: Allowances, Localized Fatigue, Musculoskeletal Disorders, and Biomechanics (not yet published)[clarification needed]

- Berlin C. & Adams C. & 2017. Production Ergonomics: Designing Work Systems to Support Optimal Human Performance. London: Ubiquity Press. doi:10.5334/bbe.

- Jan Dul and Bernard Weedmaster, Ergonomics for Beginners. A classic introduction on ergonomics—Original title: Vademecum Ergonomie (Dutch)—published and updated since the 1960s.

- Valerie J Gawron (2000), Human Performance Measures Handbook Lawrence Erlbaum Associates—A useful summary of human performance measures.

- Lee, J.D.; Wickens, C.D.; Liu Y.; Boyle, L.N. (2017). Designing for People: An introduction to human factors engineering, 3nd Edition. Charleston, SC: CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-5398-0800-8.

- Liu, Y (2007). IOE 333. Course pack. Industrial and Operations Engineering 333 (Introduction to Ergonomics), University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. Winter 2007

- Meister, D. (1999). The History of Human Factors and Ergonomics. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 978-0-8058-2769-9.

- Donald Norman, The Design of Everyday Things—An entertaining user-centered critique of nearly every gadget out there (at the time it was published)

- Peter Opsvik (2009), "Re-Thinking Sitting".[full citation needed] Interesting insights on the history of the chair and how we sit from an ergonomic pioneer

- Oviatt, S. L.; Cohen, P. R. (March 2000). "Multimodal systems that process what comes naturally". Communications of the ACM. 43 (3): 45–53. doi:10.1145/330534.330538. S2CID 1940810.

- Computer Ergonomics & Work Related Upper Limb Disorder Prevention- Making The Business Case For Pro-active Ergonomics (Rooney et al., 2008)

- Stephen Pheasant, Bodyspace—A classic exploration of ergonomics

- Sarter, N. B.; Cohen, P. R. (2002). "Multimodal information presentation in support of human-automation communication and coordination". Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research. 2: 13–36. doi:10.1016/S1479-3601(02)02004-0. ISBN 978-0-7623-0748-7.

- Smith, Thomas J.; et al. (2015). Variability in Human performance. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-7972-9.

- Alvin R. Tilley & Henry Dreyfuss Associates (1993, 2002), The Measure of Man & Woman: Human Factors in Design A human factors design manual.

- Kim Vicente, The Human Factor Full of examples and statistics illustrating the gap between existing technology and the human mind, with suggestions to narrow it

- Wickens, C.D.; Lee J.D.; Liu Y.; Gorden Becker S.E. (2003). An Introduction to Human Factors Engineering, 2nd Edition. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-321-01229-6.

- Wickens, C. D.; Sandy, D. L.; Vidulich, M. (1983). "Compatibility and resource competition between modalities of input, central processing, and output". Human Factors. 25 (2): 227–248. doi:10.1177/001872088302500209. ISSN 0018-7208. PMID 6862451. S2CID 1291342.Wu, S. (2011). "Warranty claims analysis considering human factors" (PDF). Reliability Engineering & System Safety. 96: 131–138. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2010.07.010.

- Wickens and Hollands (2000). Engineering Psychology and Human Performance. Discusses memory, attention, decision making, stress and human error, among other topics

- Wilson & Corlett, Evaluation of Human Work A practical ergonomics methodology. Warning: very technical and not a suitable 'intro' to ergonomics

- Zamprotta, Luigi, La qualité comme philosophie de la production.Interaction avec l'ergonomie et perspectives futures, thèse de Maîtrise ès Sciences Appliquées – Informatique, Institut d'Etudes Supérieures L'Avenir, Brussels, année universitaire 1992–93, TIU [1] Press, Independence, Missouri (USA), 1994, ISBN 0-89697-452-9

Peer-reviewed Journals

[edit](Numbers between brackets are the ISI impact factor, followed by the date)

- Behavior & Information Technology (0.915, 2008)

- Ergonomics (0.747, 2001–2003)

- Ergonomics in Design (-)

- Applied Ergonomics (1.713, 2015)

- Human Factors (1.37, 2015)

- International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics (0.395, 2001–2003)

- Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing (0.311, 2001–2003)

- Travail Humain (0.260, 2001–2003)

- Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science (-)

- International Journal of Human Factors and Ergonomics (-)

- International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics (-)

External links

[edit]- Directory of Design Support Methods Directory of Design Support Methods

- Engineering Data Compendium of Human Perception and Performance

- Index of Non-Government Standards on Human Engineering...

- Index of Government Standards on Human Engineering...

- NIOSH Topic Page on Ergonomics and Musculoskeletal Disorders

- Office Ergonomics Information from European Agency for Safety and Health at Work

- Human Factors Standards & Handbooks from the University of Maryland Department of Mechanical Engineering

- Human Factors and Ergonomics Resources

- Human Factors Engineering Collection, The University of Alabama in Huntsville Archives and Special Collections

Ergonomics

View on GrokipediaErgonomics, derived from the Greek words ergon (work) and nomos (natural law), is the scientific discipline that studies the interactions between humans and other elements of a system to optimize human well-being, overall performance, and safety in work systems.[1] It applies principles from physiology, psychology, biomechanics, and engineering to design tasks, tools, and environments that accommodate human capabilities and limitations, thereby reducing physical strain and enhancing efficiency.[2] The term was coined in 1857 by Polish scientist Wojciech Jastrzębowski in his work outlining the science of work adapted to human nature.[3] Ergonomic principles emphasize fitting the job to the worker rather than forcing the worker to adapt to the job, focusing on factors such as posture, repetitive motions, force exertion, and environmental conditions to prevent musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs).[2] Key guidelines include maintaining neutral body postures, minimizing excessive reaching or twisting, working at appropriate heights (often elbow level), and reducing static or awkward positions that lead to fatigue or injury.[4] These principles have been formalized in standards like ISO 6385, which provides a framework for work system design prioritizing human requirements alongside system goals.[5] Applications of ergonomics span industries including manufacturing, office environments, healthcare, and transportation, where interventions such as adjustable workstations, ergonomic tools, and task rotation have demonstrated reductions in MSD incidence, improved productivity, and decreased absenteeism.[6] Peer-reviewed studies confirm that ergonomic programs can lower work-related pain, particularly in the back and upper extremities, while boosting worker satisfaction and output through better alignment of human factors with operational demands.[7] Though empirical evidence supports these benefits, effective implementation requires ongoing assessment and adaptation to individual variability, underscoring ergonomics as an evidence-based approach grounded in causal relationships between design and human response.[8]