Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Harmonic

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

In physics, acoustics, and telecommunications, a harmonic is a sinusoidal wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the fundamental frequency of a periodic signal. The fundamental frequency is also called the 1st harmonic; the other harmonics are known as higher harmonics. As all harmonics are periodic at the fundamental frequency, the sum of harmonics is also periodic at that frequency. The set of harmonics forms a harmonic series.

The term is employed in various disciplines, including music, physics, acoustics, electronic power transmission, radio technology, and other fields. For example, if the fundamental frequency is 50 Hz, a common AC power supply frequency, the frequencies of the first three higher harmonics are 100 Hz (2nd harmonic), 150 Hz (3rd harmonic), 200 Hz (4th harmonic) and any addition of waves with these frequencies is periodic at 50 Hz.

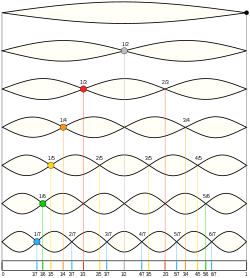

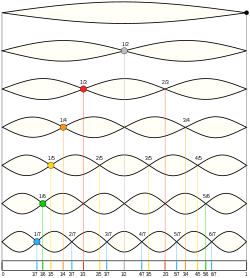

An th characteristic mode, for will have nodes that are not vibrating. For example, the 3rd characteristic mode will have nodes at and where is the length of the string. In fact, each th characteristic mode, for not a multiple of 3, will not have nodes at these points. These other characteristic modes will be vibrating at the positions and If the player gently touches one of these positions, then these other characteristic modes will be suppressed. The tonal harmonics from these other characteristic modes will then also be suppressed. Consequently, the tonal harmonics from the th characteristic characteristic modes, where is a multiple of 3, will be made relatively more prominent.[1]

In music, harmonics are used on string instruments and wind instruments as a way of producing sound on the instrument, particularly to play higher notes and, with strings, obtain notes that have a unique sound quality or "tone colour". On strings, bowed harmonics have a "glassy", pure tone. On stringed instruments, harmonics are played by touching (but not fully pressing down the string) at an exact point on the string while sounding the string (plucking, bowing, etc.); this allows the harmonic to sound, a pitch which is always higher than the fundamental frequency of the string.

Terminology

[edit]Harmonics may be called "overtones", "partials", or "upper partials", and in some music contexts, the terms "harmonic", "overtone" and "partial" are used fairly interchangeably. But more precisely, the term "harmonic" includes all pitches in a harmonic series (including the fundamental frequency) while the term "overtone" only includes pitches above the fundamental.

Characteristics

[edit]A whizzing, whistling tonal character, distinguishes all the harmonics both natural and artificial from the firmly stopped intervals; therefore their application in connection with the latter must always be carefully considered.[citation needed]

— Richard Scholz (c. 1888–1912)[2]

Most acoustic instruments emit complex tones containing many individual partials (component simple tones or sinusoidal waves), but the untrained human ear typically does not perceive those partials as separate phenomena. Rather, a musical note is perceived as one sound, the quality or timbre of that sound being a result of the relative strengths of the individual partials. Many acoustic oscillators, such as the human voice or a bowed violin string, produce complex tones that are more or less periodic, and thus are composed of partials that are nearly matched to the integer multiples of fundamental frequency and therefore resemble the ideal harmonics and are called "harmonic partials" or simply "harmonics" for convenience (although it's not strictly accurate to call a partial a harmonic, the first being actual and the second being theoretical).

Oscillators that produce harmonic partials behave somewhat like one-dimensional resonators, and are often long and thin, such as a guitar string or a column of air open at both ends (as with the metallic modern orchestral transverse flute). Wind instruments whose air column is open at only one end, such as trumpets and clarinets, also produce partials resembling harmonics. However they only produce partials matching the odd harmonics—at least in theory. In practical use, no real acoustic instrument behaves as perfectly as the simplified physical models predict; for example, instruments made of non-linearly elastic wood, instead of metal, or strung with gut instead of brass or steel strings, tend to have not-quite-integer partials.

Partials whose frequencies are not integer multiples of the fundamental are referred to as inharmonic partials. Some acoustic instruments emit a mix of harmonic and inharmonic partials but still produce an effect on the ear of having a definite fundamental pitch, such as pianos, strings plucked pizzicato, vibraphones, marimbas, and certain pure-sounding bells or chimes. Antique singing bowls are known for producing multiple harmonic partials or multiphonics.[3][4] Other oscillators, such as cymbals, drum heads, and most percussion instruments, naturally produce an abundance of inharmonic partials and do not imply any particular pitch, and therefore cannot be used melodically or harmonically in the same way other instruments can.

Building on of Sethares (2004),[5] dynamic tonality introduces the notion of pseudo-harmonic partials, in which the frequency of each partial is aligned to match the pitch of a corresponding note in a pseudo-just tuning, thereby maximizing the consonance of that pseudo-harmonic timbre with notes of that pseudo-just tuning.[6][7][8][9]

Partials, overtones, and harmonics

[edit]An overtone is any partial higher than the lowest partial in a compound tone. The relative strengths and frequency relationships of the component partials determine the timbre of an instrument. The similarity between the terms overtone and partial sometimes leads to their being loosely used interchangeably in a musical context, but they are counted differently, leading to some possible confusion. In the special case of instrumental timbres whose component partials closely match a harmonic series (such as with most strings and winds) rather than being inharmonic partials (such as with most pitched percussion instruments), it is also convenient to call the component partials "harmonics", but not strictly correct, because harmonics are numbered the same even when missing, while partials and overtones are only counted when present. This chart demonstrates how the three types of names (partial, overtone, and harmonic) are counted (assuming that the harmonics are present):

| Frequency | Order (n) |

Name 1 | Name 2 | Name 3 | Standing wave representation | Longitudinal wave representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × f = 440 Hz | n = 1 | 1st partial | fundamental tone | 1st harmonic |

|

|

| 2 × f = 880 Hz | n = 2 | 2nd partial | 1st overtone | 2nd harmonic |

|

|

| 3 × f = 1320 Hz | n = 3 | 3rd partial | 2nd overtone | 3rd harmonic |

|

|

| 4 × f = 1760 Hz | n = 4 | 4th partial | 3rd overtone | 4th harmonic |

|

|

In many musical instruments, it is possible to play the upper harmonics without the fundamental note being present. In a simple case (e.g., recorder) this has the effect of making the note go up in pitch by an octave, but in more complex cases many other pitch variations are obtained. In some cases it also changes the timbre of the note. This is part of the normal method of obtaining higher notes in wind instruments, where it is called overblowing. The extended technique of playing multiphonics also produces harmonics. On string instruments it is possible to produce very pure sounding notes, called harmonics or flageolets by string players, which have an eerie quality, as well as being high in pitch. Harmonics may be used to check at a unison the tuning of strings that are not tuned to the unison. For example, lightly fingering the node found halfway down the highest string of a cello produces the same pitch as lightly fingering the node 1 / 3 of the way down the second highest string. For the human voice see Overtone singing, which uses harmonics.

While it is true that electronically produced periodic tones (e.g. square waves or other non-sinusoidal waves) have "harmonics" that are whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency, practical instruments do not all have this characteristic. For example, higher "harmonics" of piano notes are not true harmonics but are "overtones" and can be very sharp, i.e. a higher frequency than given by a pure harmonic series. This is especially true of instruments other than strings, brass, or woodwinds. Examples of these "other" instruments are xylophones, drums, bells, chimes, etc.; not all of their overtone frequencies make a simple whole number ratio with the fundamental frequency. (The fundamental frequency is the reciprocal of the longest time period of the collection of vibrations in some single periodic phenomenon.[10])

On stringed instruments

[edit]

Harmonics may be singly produced [on stringed instruments] (1) by varying the point of contact with the bow, or (2) by slightly pressing the string at the nodes, or divisions of its aliquot parts (, , , etc.). (1) In the first case, advancing the bow from the usual place where the fundamental note is produced, towards the bridge, the whole scale of harmonics may be produced in succession, on an old and highly resonant instrument. The employment of this means produces the effect called 'sul ponticello.' (2) The production of harmonics by the slight pressure of the finger on the open string is more useful. When produced by pressing slightly on the various nodes of the open strings they are called 'natural harmonics'. ... Violinists are well aware that the longer the string in proportion to its thickness, the greater the number of upper harmonics it can be made to yield.

The following table displays the stop points on a stringed instrument at which gentle touching of a string will force it into a harmonic mode when vibrated. String harmonics (flageolet tones) are described as having a "flutelike, silvery quality" that can be highly effective as a special color or tone color (timbre) when used and heard in orchestration.[12] It is unusual to encounter natural harmonics higher than the fifth partial on any stringed instrument except the double bass, on account of its much longer strings.[12]

| Harmonic order | Stop note | Note sounded (relative to open string) |

Audio frequency (Hz) | Cents above fundamental (offset by octave) |

Audio (octave shifted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | fundamental, perfect unison |

P 1 | 600Hz | 0.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 2nd | first perfect octave | P 8 | 1200Hz | 0.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 3rd | perfect fifth | P 8 + P 5 | 1800Hz | 702.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 4th | doubled perfect octave | 2 · P 8 | 2400Hz | 0.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 5th | just major third, major third |

2 · P 8 + M 3 | 3000Hz | 386.3 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 6th | perfect fifth | 2 · P 8 + P 5 | 3600Hz | 702.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 7th | harmonic seventh, septimal minor seventh (‘the lost chord’) |

2 · P 8 + m 7↓ | 4200Hz | 968.8 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 8th | third perfect octave | 3 · P 8 | 4800Hz | 0.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 9th | Pythagorean major second harmonic ninth |

3 · P 8 + M 2 | 5400Hz | 203.9 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 10th | just major third | 3 · P 8 + M 3 | 6000Hz | 386.3 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 11th | lesser undecimal tritone, undecimal semi-augmented fourth |

3 · P 8 + A 4 |

6600Hz | 551.3 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 12th | perfect fifth | 3 · P 8 + P 5 | 7200Hz | 702.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 13th | tridecimal neutral sixth | 3 · P 8 + n 6 |

7800Hz | 840.5 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 14th | harmonic seventh, septimal minor seventh (‘the lost chord’) |

3 · P 8 + m 7⤈ | 8400Hz | 968.8 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 15th | just major seventh | 3 · P 8 + M 7 | 9000Hz | 1088.3 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 16th | fourth perfect octave | 4 · P 8 | 9600Hz | 0.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 17th | septidecimal semitone | 4 · P 8 + m 2⇟ | 10200Hz | 105.0 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 18th | Pythagorean major second | 4 · P 8 + M 2 | 10800Hz | 203.9 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 19th | nanodecimal minor third | 4 · P 8 + m 3 |

11400Hz | 297.5 ¢ | ⓘ |

| 20th | just major third | 4 · P 8 + M 3 | 12000Hz | 386.3 ¢ | ⓘ |

| P | perfect interval |

| A | augmented interval (sharpened) |

| M | major interval |

| m | minor interval (flattened major) |

| n | neutral interval (between major and minor) |

| half-flattened (approximate) (≈ −38 ¢ for just, −50 ¢ for 12 TET) | |

| ↓ | flattened by a syntonic comma (approximate) (≈ −21 ¢ ) |

| ⤈ | flattened by a half-comma (approximate) (≈ −10 ¢ ) |

| ⇟ | flattened by a quarter-comma (approximate) (≈ −5 ¢ ) |

Artificial harmonics

[edit]Occasionally a score will call for an artificial harmonic, produced by playing an overtone on an already stopped string. As a performance technique, it is accomplished by using two fingers on the fingerboard, the first to shorten the string to the desired fundamental, with the second touching the node corresponding to the appropriate harmonic.

Other information

[edit]Harmonics may be either used in or considered as the basis of just intonation systems. Composer Arnold Dreyblatt is able to bring out different harmonics on the single string of his modified double bass by slightly altering his unique bowing technique halfway between hitting and bowing the strings. Composer Lawrence Ball uses harmonics to generate music electronically.

See also

[edit]- Aristoxenus – 4th century BC Greek Peripatetic philosopher

- Electronic tuner – Device used to tune musical instruments

- Formant – Spectrum of phonetic resonance in speech production

- Fourier series – Decomposition of periodic functions

- Guitar harmonic – String instrument technique

- Harmonic analysis – Study of superpositions in mathematics

- Harmonics (electrical power) – Sinusoidal wave whose frequency is an integer multiple

- Harmonic generation – Nonlinear optical process

- Harmonic oscillator – Physical system that responds to a restoring force inversely proportional to displacement

- Harmony – Aspect of music

- Pure tone – Sound with a sinusoidal waveform

- Pythagorean tuning – Method of tuning a musical instrument

- Scale of harmonics

- Spherical harmonics – Special mathematical functions defined on the surface of a sphere

- Stretched octave – Musical interval which is not a perfect harmonic

- Subharmonic – Having a frequency that is a fraction of a fundamental frequency

- Xenharmonic music – Music that uses a tuning system outside of 12-TET

References

[edit]- ^ Walker, Russell (14 June 2019). "Russell Walker". Authors' group (online magazine). Catonsville, MD: Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences. doi:10.1287/7648739e-8e59-466e-82cb-3ded22bbebf6. S2CID 241172832. Retrieved 21 December 2020 – via informs.scienceconnect.io.

- ^ "Category:Scholz, Richard". Petrucci Music Library / International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) (imslp.org) (site sub-index & mini-bio for Scholz). Canada. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ^

Galembo, Alexander; Cuddly, Lola L. (2 December 1997). "Large grand and small upright pianos". acoustics.org (Press release). Acoustical Society of America. Archived from the original on 2012-02-09. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

There are many ways to make matters worse, but very few to improve.

— Minimally technical summary of string acoustics research given at conference; discusses listeners' perceptions of pianos' inharmonic partials. - ^ Court, Sophie R.A. (April 1927). "Golo und Genovefa [by] Hanna Rademacher". Books Abroad (book review). 1 (2): 34–36. doi:10.2307/40043442. ISSN 0006-7431. JSTOR 40043442.

- ^ Sethares, W.A. (2004). Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale. Springer. ISBN 978-1852337971 – via Google books.

- ^ Sethares, W.A.; Milne, A.; Tiedje, S.; Prechtl, A.; Plamondon, J. (2009). "Spectral tools for dynamic tonality and audio morphing". Computer Music Journal. 33 (2): 71–84. doi:10.1162/comj.2009.33.2.71. S2CID 216636537.

- ^ Milne, Andrew; Sethares, William; Plamondon, James (29 August 2008). "Tuning continua and keyboard layouts" (PDF). Journal of Mathematics and Music. 2 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/17459730701828677. S2CID 1549755. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. "Alt URL" (PDF). Sethares pers. academic site. University of Wisconsin.

- ^ Milne, A.; Sethares, W.A.; Plamondon, J. (Winter 2007). "Invariant fingerings across a tuning continuum". Computer Music Journal. 31 (4): 15–32. doi:10.1162/comj.2007.31.4.15. S2CID 27906745.

- ^ Milne, A.; Sethares, W.A.; Plamondon, J. (2006). X System (PDF) (technical report). Thumtronics Inc. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

- ^ Grove, George (1879). A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450–1889), Vol. 2, p. 665. Macmillan. [ISBN unspecified].

- ^ a b Marrocco, W. Thomas (2001). "Kennan, Kent". Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.14882. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

External links

[edit]- The Feynman Lectures on Physics: Harmonics

- Harmonics, partials and overtones from fundamental frequency

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Harmonics

- Hear and see harmonics on a Piano

- Configurable animated SVG representation of base tone with harmonics

Harmonic

View on GrokipediaBasic Concepts

Definition

In the context of waves and oscillations, a harmonic is a component frequency of a periodic wave whose frequency is an integer multiple of the fundamental frequency, which is the lowest frequency present in the wave.[2] This fundamental frequency, often denoted as , serves as the reference, and higher harmonics build upon it to form more complex waveforms.[4] The term "harmonic" originates from the Greek word harmonia, meaning "harmony" or "joint," reflecting its early association with musical consonance, and entered English usage in the 1560s to describe musical relations.[5] It was first systematically explored by the ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras around 500 BCE, who observed that pleasing musical intervals arise from simple integer ratios of string lengths or frequencies, laying the groundwork for understanding harmonic relationships in vibrations.[6] A pure sine wave embodies a single harmonic, corresponding to either the fundamental or one of its multiples, whereas real-world periodic waves are typically superpositions of multiple harmonics. This decomposition principle was formalized by Joseph Fourier in 1822, who demonstrated that any periodic function can be represented as an infinite sum of sine and cosine waves at harmonic frequencies.[7] Mathematically, the frequency of the -th harmonic is expressed as: where is the fundamental frequency and . For , this yields the fundamental itself, often considered the first harmonic.[4]Terminology

In acoustics and music theory, a harmonic refers to a sinusoidal component of a complex sound wave whose frequency is an integer multiple of the fundamental frequency.[8] A partial, in contrast, denotes any sinusoidal frequency component within a sound, which may include both harmonic (integer multiples) and inharmonic (non-integer multiples) elements. An overtone encompasses any frequency above the fundamental, typically starting with the second harmonic as the first overtone, though it can apply to both harmonic and inharmonic partials.[9] Conventions for numbering these components vary between physics and music. In physics and engineering, harmonics are indexed starting from the fundamental as the first harmonic (n=1), with subsequent harmonics at integer multiples (n=2, 3, etc.). In music, overtones are often enumerated beginning above the fundamental, such that the first overtone aligns with the second harmonic, emphasizing the perceptual series beyond the perceived pitch.[10] A common confusion arises when "harmonic" is misused to describe any overtone, blurring the distinction from partials; international standards, such as IEC 801-30-03, clarify that harmonics must be exact integer multiples to avoid this ambiguity.[8] The terminology's historical evolution includes Marin Mersenne's early classification in his 1636 treatise Harmonie universelle, where he identified and described the first several harmonics audible in string and vocal sounds, laying groundwork for later acoustic analysis.[11] These distinctions underpin the structure of the harmonic series addressed elsewhere in this entry.Properties and Analysis

Characteristics

In acoustics, harmonics are sinusoidal components of a complex wave whose frequencies are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency, denoted as , where is a positive integer and is the fundamental. This precise frequency relationship ensures that the overall waveform remains periodic with the same period as the fundamental, enabling constructive and destructive interference among the components that shapes the resulting sound wave. For instance, when harmonics align in phase at certain points, they reinforce each other through constructive interference, amplifying the wave amplitude, while out-of-phase alignments lead to destructive interference, reducing it.[12] The amplitude of harmonics typically decreases as the harmonic number increases in natural vibrating systems, often following a spectral slope where higher-frequency components have progressively lower amplitudes. This amplitude distribution, combined with phase relationships among the harmonics, determines the time-domain shape of the waveform; for example, shifts in phase can alter the waveform from smooth to peaked without changing the frequency spectrum. In Fourier analysis, these phase differences are crucial for reconstructing the original signal, as identical amplitude spectra can yield different waveforms depending on phase alignment.[13][14] Energy in harmonic components is unevenly distributed, with higher harmonics carrying less total energy than lower ones, which contributes to the perceptual decay of timbre over time as higher frequencies attenuate more rapidly due to factors like medium absorption. This energy gradient influences how sounds evolve, with initial richness from multiple harmonics giving way to a more fundamental-dominated tone. Observable effects of harmonics include contributions to perceived brightness, where stronger higher harmonics enhance clarity and sharpness, and nasality, arising when specific harmonics are amplified by nasal resonances, creating a resonant emphasis in the mid-frequency range. In Fourier analysis, even harmonics (multiples of 2) promote waveform symmetry associated with warmer timbres, while odd harmonics (multiples of 1, 3, etc.) introduce asymmetry linked to brighter or more edged qualities.[15][16][17][18]Mathematical Representation

The mathematical representation of harmonics fundamentally relies on the Fourier series, which decomposes any periodic function into a sum of sinusoidal components at integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. For a periodic function with period , where is the fundamental frequency, the Fourier series is given by where the coefficients are determined by integrals over one period: , , and for .[19] This expansion represents the function as a superposition of the fundamental tone and its harmonics, with the th harmonic corresponding to the term at frequency . The derivation of these coefficients stems from the orthogonality of the sine and cosine functions over the interval . Specifically, the set forms an orthogonal basis, meaning for , and similarly for sine-sine and sine-cosine products, with normalization integrals yielding for and for the constant term.[20] This orthogonality ensures a unique decomposition, as multiplying the series by a basis function and integrating isolates each coefficient, providing a rigorous foundation for harmonic analysis.[19] An equivalent complex exponential form leverages Euler's formula, expressing the series as where the complex coefficients satisfy for , , and . This formulation simplifies computations in signal processing, as the harmonics appear symmetrically around the frequency axis. In practice, the harmonic content of a signal is analyzed through the spectrum, obtained efficiently via the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), an algorithm developed by Cooley and Tukey in 1965 that computes the discrete Fourier transform in time for samples, enabling decomposition into harmonic amplitudes and phases.[21] This tool is essential for visualizing and quantifying the distribution of energy across harmonics in periodic waveforms.Harmonic Series

Partials, Overtones, and Harmonics

In the context of wave decomposition, partials refer to all the individual sinusoidal frequency components that make up a complex tone, encompassing both harmonic and inharmonic elements.[22] Unlike harmonics, which are strictly integer multiples of the fundamental frequency, partials include any resonant frequencies present in the spectrum, regardless of their ratio to the fundamental. For instance, in sounds produced by bells, the partials often deviate from integer ratios due to the irregular geometry and material properties of the instrument, resulting in inharmonic partials that contribute to the distinctive timbre.[23] Overtones, by contrast, specifically denote the frequency components above the fundamental frequency, excluding the fundamental itself from the count.[24] In a purely harmonic series, the first overtone corresponds to the second harmonic (twice the fundamental frequency), the second overtone to the third harmonic, and so on.[25] This terminology highlights the hierarchical structure of the spectrum, where overtones build upon the fundamental to form the overall sound quality, though they may include inharmonic components in non-ideal vibrations.[26] The key distinction between harmonics and other partials or overtones lies in their frequency relationships: harmonics are precisely the integer multiples of the fundamental (e.g., , , , etc.), arising from regular, periodic vibrations, while non-harmonic partials occur in irregular or asymmetric systems where frequencies do not align as integers.[22] This can be observed in synthesized waveforms; for example, a square wave decomposes into the fundamental plus only odd harmonics (such as , , , etc.), with amplitudes decreasing as where is the harmonic number./08%3A_Mixed-Frequency_AC_Signals/8.02%3A_Square_Wave_Signals) In comparison, a sawtooth wave includes all harmonics (both odd and even multiples of ), also with amplitudes falling off as , producing a fuller spectral content.[27] These examples illustrate how harmonic content shapes timbre through Fourier decomposition, as explored further in the mathematical representation of harmonics.Harmonic Series in Waves

In periodic waves, the harmonic series forms an ordered sequence where the fundamental frequency is accompanied by higher harmonics at integer multiples , , ..., , with corresponding wavelengths for the th harmonic, where is the fundamental wavelength. This structure arises in standing waves on strings or in air columns, where each harmonic represents a resonant mode that fits an integer number of half-wavelengths within the vibrating medium.[4] For an ideal string under uniform tension, the harmonics maintain exact integer frequency ratios, ensuring equal linear spacing between consecutive partials in the frequency domain.[28] The timbre of a sound wave is shaped by the relative strengths of these harmonics, as the amplitude distribution across the series imparts unique qualitative characteristics to the overall waveform./05%3A_The_Physical_Basis/5.03%3A_Harmonic_Series_I-_Timbre_and_Octaves) Instruments produce distinct timbres because their physical properties emphasize certain harmonics over others; for instance, a clarinet's odd harmonics dominate due to its cylindrical bore, creating a reedy quality, while a flute's more even distribution yields a purer tone.[29] In the case of an ideal string, the harmonic series contributes to a bright, metallic timbre when lower harmonics are stronger, but real-world variations in amplitude decay with increasing , softening higher frequencies./05%3A_The_Physical_Basis/5.03%3A_Harmonic_Series_I-_Timbre_and_Octaves) During propagation, harmonics in a linear non-dispersive medium travel at the same phase velocity, maintaining the relative phase relationships and thus preserving the original waveform shape over distance.[30] This is evident in sound waves through air at audio frequencies, where the medium's uniformity prevents distortion from differential speeds. In nonlinear media, however, wave steepening occurs due to amplitude-dependent velocity, generating new higher harmonics and causing dispersion that alters the waveform profile.[31] Real wave systems often exhibit inharmonicity, where partial frequencies deviate from ideal integer multiples because of material properties like stiffness. In piano strings, longitudinal stretching under tension combined with bending stiffness raises the frequencies of higher partials, making them progressively sharper than the harmonic series predicts.[32] This effect, quantified by an inharmonicity coefficient to depending on string length and tension, increases with , contributing to the piano's characteristic warm yet tense timbre and necessitating stretched tuning for consonant intervals.[33]Production in Musical Instruments

Stringed Instruments

In stringed instruments, harmonics arise from the standing wave patterns formed when a string vibrates while fixed at both ends, such as the nut and bridge. The natural modes of vibration divide the string into an integer number of equal segments, with nodal points—locations of zero transverse displacement—occurring at positions that are multiples of one-nth of the string's total length for the nth harmonic.[34] For the fundamental mode (first harmonic), the string forms a single loop with nodes only at the ends and an antinode at the center; the second harmonic creates two loops with an additional node at the midpoint, and higher modes follow similarly, producing frequencies that are integer multiples of the fundamental.[4] These modes determine the possible pitches available on open strings, and lightly touching the string at nodal points isolates specific higher harmonics for performance.[35] The harmonic spectrum of a stringed instrument varies based on the excitation method, influencing timbre and decay. Plucked strings, as in guitars or harps, start with a sharp triangular displacement that excites a broad range of both odd and even harmonics, with higher ones prominent initially if plucked near the end but decaying faster than lower partials due to greater energy dissipation.[36] Bowed strings, such as those on violins or cellos, generate a periodic sawtooth waveform through friction with the bow, sustaining a full series of both odd and even harmonics, with odd ones contributing to brightness, and the overall spectrum remains steady longer because the bowing continuously replenishes energy across modes.[37] This difference in spectral emphasis gives plucked instruments a transient, sparkling quality and bowed ones a sustained, complex resonance.[38] Harmonics play a key role in tuning and intonation for stringed instruments, enabling precise alignment of intervals based on the natural frequency ratios of the series. In just intonation, musicians tune intervals like the perfect fourth by matching the fourth harmonic of the lower note to the third harmonic of the upper note, yielding a 4:3 ratio that produces pure consonance without beats. Similarly, the perfect fifth aligns the third harmonic of the lower pitch with the second of the upper, at a 3:2 ratio, which string players often verify by ear during ensemble performance.[39] Historically, Pythagorean tuning, attributed to Pythagoras in the 6th century BCE, established early string-based scales using simple length ratios under uniform tension, such as 2:1 for the octave and 3:2 for the fifth, derived from comparing monochord strings to generate a diatonic series through stacked fifths.[40] This system prioritized consonant intervals from powers of 2 and 3 but introduced dissonant thirds, limiting modulation.[41] In modern contexts, equal temperament divides the octave logarithmically into 12 equal semitones for versatility across keys, with tuners adjusting for inharmonicity—the stiffening of strings that causes higher partials to rise slightly above integer multiples—by stretching octaves upward by 10-30 cents in pianos to balance perceived pitch.[42]Wind and Other Instruments

In wind instruments, harmonics are produced through the resonance of an air column within a cylindrical or conical tube. The fundamental and higher harmonics depend on whether the pipe is open or closed at one end. For open pipes (both ends open, e.g., flute), the fundamental mode has wavelength λ = 2L (L effective length), with frequencies f_n = n v/(2L) for integers n=1,2,3,... . For closed-open pipes (e.g., clarinet), the fundamental has λ = 4L, with only odd harmonics f_n = (2n-1) v/(4L) for n=1,3,5,... . Conical bores (e.g., oboe, saxophone) and brass instruments approximate a full harmonic series due to their geometry and bell flare, despite starting from a closed model.[43][44] The player's lips (in brass instruments) or reed (in woodwinds) act as the exciter, coupling with the air column to select and amplify specific resonant modes from this harmonic series.[45] Brass instruments, excited by lip vibration that generates a periodic train of air pulses akin to a square-like waveform, tend to emphasize odd harmonics in their basic cylindrical model but produce a full series including even harmonics due to the bell, contributing to their bright, projecting timbre.[46] In contrast, woodwind instruments vary: cylindrical ones like the clarinet, driven by reed vibrations producing a waveform emphasizing odd harmonics, result in a focused tone; conical woodwinds, with reed vibrations yielding a more complex waveform akin to a sawtooth, exhibit a mix of even and odd harmonics, resulting in a richer tone quality.[47] Players adjust the excited harmonics through embouchure (lip positioning and tension) or fingering techniques, which alter the effective tube length or impedance to favor certain overtones. For instance, in the trumpet, pedal tones exploit the lowest harmonics—such as the fundamental or second partial—of the instrument's air column resonance for sub-pitch effects below the standard range.[48] Unlike stringed instruments that rely on transverse vibrations under tension, percussion instruments generate harmonics through impact excitation of membranes or plates, often yielding inharmonic partials due to their two-dimensional nature. Drums, for example, feature non-integer frequency ratios among partials from the vibrating membrane modes, producing indefinite pitch suitable for rhythmic roles.[49] Cymbals, struck to excite numerous closely spaced modes in a thin metal plate, yield complex, non-periodic spectra with rapidly decaying inharmonic components, creating their characteristic shimmering sustain without a defined pitch.[49]Techniques and Applications

Artificial Harmonics

Artificial harmonics are produced on string instruments by lightly touching the string at a nodal point—such as halfway (1/2 length) or one-third (1/3 length) along its vibrating segment—while simultaneously stopping the string with another finger and bowing or plucking to isolate higher overtones and suppress the fundamental frequency.[50] This technique divides the string into segments that favor specific harmonic modes, resulting in a pure, flute-like tone often called a flageolet.[51] On the violin, artificial harmonics commonly produce the fourth partial, sounding an octave plus a perfect fifth above the stopped note; for instance, stopping the G string at the fourth finger position (D) and lightly touching a perfect fourth above yields the high D (two octaves above).[52] Guitarists perform artificial harmonics by fretting a note and lightly touching the string at nodes like the 12th fret (producing an octave above the fretted pitch) or the 7th fret (yielding an octave plus a fifth), which enhances the instrument's extended range in classical and contemporary compositions.[53] In wind instruments, artificial harmonics arise through deliberate embouchure and breath adjustments to select higher partials beyond the fundamental. Flutists achieve this via overblowing, where increased air velocity and lip adjustment—such as rolling inward to narrow the airstream—excite the second or third harmonic, enabling access to the instrument's upper register without altering fingerings significantly.[54] On the didgeridoo, performers use vocal tract shaping, including tongue and throat adjustments, to emphasize specific odd harmonics in the instrument's drone, creating multiphonic effects or melodic overtones through controlled resonance filtering.[55] In musical notation, artificial harmonics on strings are typically indicated by a small diamond-shaped notehead above or beside the stopped note, representing the touch position, while the fundamental is shown with a standard notehead; this dual notation guides the performer on precise finger placement.[56] For winds like the flute, overblown harmonics may be marked with an arrow or "ott." (ottava) indication, though context often implies the technique. Performance challenges include maintaining accurate intonation, as pure harmonics deviate from equal temperament, and achieving sufficient volume, since higher partials are inherently weaker and require precise control to avoid wolf tones or instability.[57]Harmonics in Acoustics and Physics

In acoustics, harmonics play a critical role in room modes, where standing waves form due to reflections off boundaries, leading to frequency-specific boosts or attenuations that can cause echoes or uneven sound distribution. These modes arise from the harmonic resonances of the room's dimensions, with axial modes (involving two parallel walls) being the strongest, potentially creating nulls or peaks at multiples of the fundamental frequency determined by the room's length, width, and height. For instance, in a rectangular room, the lowest mode frequency is , where is the speed of sound and is the dimension, with higher harmonics at integer multiples exacerbating issues like bass buildup or treble loss in listening environments.[58][59] Harmonic distortion in audio systems, quantified by total harmonic distortion (THD), measures the ratio of unwanted harmonic components to the fundamental signal, often becoming audible when exceeding 1% for even-order harmonics or 0.1% for odd-order ones in listening tests. This distortion introduces spurious frequencies that alter perceived timbre, with thresholds varying by harmonic order and signal level; for example, third-harmonic distortion is noticeable around -55 to -60 dB relative to the fundamental. In engineering practice, audio equipment is designed to keep THD below 0.1% to ensure fidelity, as higher levels degrade clarity in reproduction systems.[60][61] In physics, simple harmonic motion (SHM) forms the foundational model for harmonic phenomena, described by the displacement equation , where is amplitude, is angular frequency, is frequency, is time, and is phase constant. This motion underlies oscillatory systems like pendulums or springs, where restoring force is proportional to displacement, leading to periodic behavior invariant in form under superposition. Extending to quantum mechanics, the quantum harmonic oscillator models vibrational energy levels in molecules and solids, with quantized energies for quantum number , first rigorously solved by Max Born and Pascual Jordan in 1925, as part of the development of matrix mechanics initiated by Werner Heisenberg.[62] In engineering applications, harmonics require filtering in power systems to mitigate issues like overheating from triplen (third-order and multiples) currents, which add in the neutral conductor of three-phase systems due to nonlinear loads such as rectifiers. These zero-sequence harmonics, particularly the third, circulate without phase cancellation, increasing losses and voltage distortion; standards like IEEE 519 limit total harmonic voltage distortion to 5% with individual harmonics below 3%. In nonlinear optics, harmonic generation in lasers—pioneered post-1961 with second-harmonic generation (SHG) doubling frequency via crystals like KDP—enables applications in spectroscopy and ultrafast pulse shaping.[64][65][66] Modern uses extend to medical imaging, where harmonic analysis corrects geometric distortions in MRI caused by gradient field nonlinearities, mapping inhomogeneities up to third order for sub-millimeter accuracy in radiotherapy planning. In oceanography and climate modeling, Fourier harmonic decomposition analyzes ENSO variability by isolating periodic components in sea surface temperature time series, aiding predictions of interannual oscillations through spectral methods.[67][68][69]References

- https://www.violinwiki.org/wiki/Harmonics

- Book%3A_University_Physics_I_-Mechanics_Sound_Oscillations_and_Waves(OpenStax)/15%3A_Oscillations/15.02%3A_Simple_Harmonic_Motion