Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

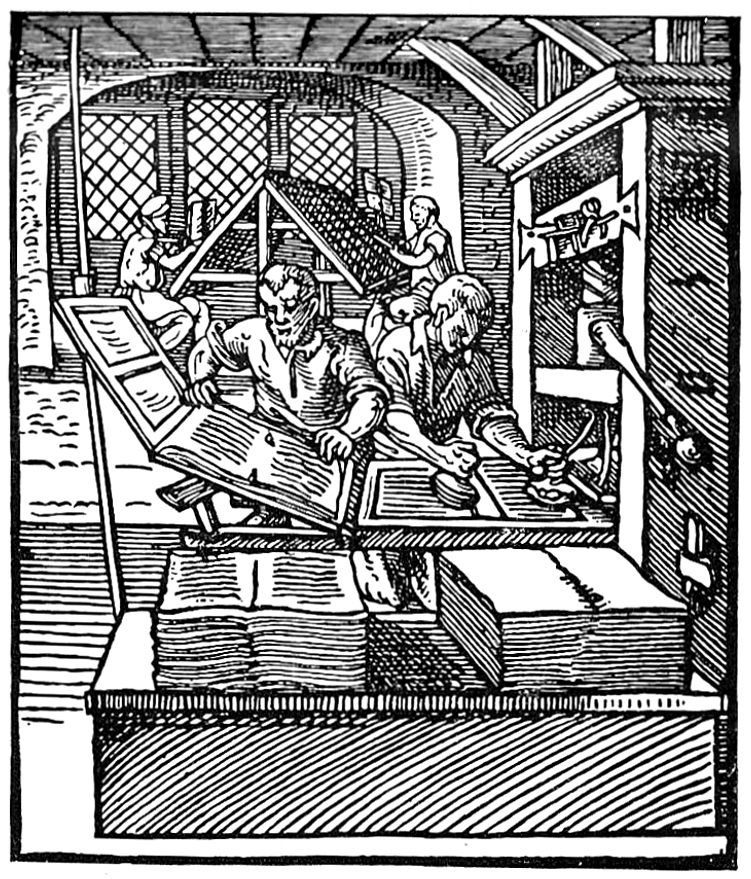

Printer's devil

View on Wikipedia

A printer's devil was a young apprentice in a printing establishment who performed a number of tasks, such as mixing tubs of ink and fetching type. Writers including Benjamin Franklin, Walt Whitman, Ambrose Bierce, Bret Harte, Sherwood Anderson, and Mark Twain served as printer's devils in their youth along with indentured servants.

There are religious, literary, and linguistic hypotheses for the etymology. Printers blamed the mischievous devil Titivillus or confused a name with the legend Faust. Other theories include racism, Gallicisms, or misspellings.

Etymology

[edit]

The term "printer's devil" has been ascribed to the apprentices' hands and skin getting stained black with ink when removing sheets of paper from the tympan.[1] In 1683, English printer Joseph Moxon wrote that "devil" was a humorous term for boys who were covered in ink: "whence the Workmen do Jocosely call them Devils; and sometimes Spirits, and sometimes Flies."[2][3] Once cast metal type was used, worn, or broken, it was thrown into a "hellbox", after which it was the printer's devil's job to either put it back in the job case, or take it to the furnace to be melted down and recast.[4]

Many explanations have been given for the religious or supernatural connotations of the term.[5] From the Middle Ages onward, particularly in Catholic countries, technological inventions such as the printing press were often regarded with suspicion, and associated with Satan and the "Dark Arts".[6][7] Some have suggested that the term was coined as an epithet by scribes who feared that the printing press would make the hand-copying of manuscripts obsolete.[8] Several theories of the term's origins are included below.

Titivillus

[edit]One popular theory is linked to the fanciful belief among printers that a special demon, Titivillus (also referred to as "the original printer's devil"[9]), haunted every print shop, performing mischief such as inverting type, misspelling words, and removing entire lines of completed type.[citation needed] Titivillus was said to execute his pranks by influencing the young apprentices – or "printer's devils" – as they set up type, or by causing errors to occur during the actual casting of metal type.[10] High-profile printing errors "blamed" on Titivillus included the omission of the word not in the 1631 Authorised Version of the Bible, which resulted in Exodus 20:14 appearing as "Thou shalt commit adultery."[10] Often depicted as a creature with claw-like feet and horns on his head, the origins of the Titivillus legend date back to the Middle Ages, when he was said to collect "fragments of words" that were dropped or misspoken by the clergy or laiety in a sack to deliver to Satan daily, and later, to record poorly recited prayers and gossip overheard in church with a pen on parchment, for use on Judgement Day.[10][11] Over the centuries, Titivillus was also blamed for causing monks to make mistakes while copying manuscripts by hand; meddling with block and plate printing; and eventually, playing pranks with movable type.[10]

Johann Fust

[edit]Regarding the origins of the term "devil" to refer to "the errand boy or youngest apprentice in a printing office", Pasko's American Dictionary of Printing and Bookmaking (1894) states: "It is said that it is derived from the belief that John Fust was In league with the devil, and the urchin covered with ink certainly made a very good representation of his Satanic majesty."[2] Johann Fust (c.1400–1466), also known as Faust, loaned money to Johannes Gutenberg to perfect his printing process using movable type, and sued Gutenberg for repayment, with interest, in 1455.[12] Fust, together with Gutenberg's son-in-law Peter Schoeffer, then set up their own printing business and published the Mainz Psalter, a Bible which introduced colour printing, in 1457.[12] Over the centuries, biographical accounts of Fust, the printer, have often become confused or intertwined with the legend of Johann Georg Faust (c.1480–1540), the alchemist and necromancer who became the subject of numerous "Faust books" published in Germany starting in 1587, which in turn inspired Christopher Marlowe's work, Doctor Faustus (c.1591–1593).[13] The legendary Faustus is said to have sold his soul to the demon Mephistopheles, in exchange for a book or encyclopedia of magical spells.[13] In 1570, even before publication of the first Faustbuch, English church historian John Foxe credited "a Germaine...named Joan. Faustus, a goldesmith" for the invention of the printing press, in the second edition of Actes and Monuments, although he had previously attributed its invention to "Jhon Guttenbergh".[13] Literary scholar Sarah Wall-Rendell argues that the association of the Doctor Faustus legend with books and printing technology reflected ongoing ambivalence among Reformation writers about the impact that books would have on an increasingly literate populace.[13]

Aldus Manutius

[edit]Yet another possible origin is ascribed to Aldus Manutius, a Venetian printer (fl. 1450-1515), who was denounced by detractors for practicing the black arts as early printing was long associated with devilry.[14] The assistant to Manutius was a young boy of African descent who was accused of being the embodiment of Satan and dubbed the printer's devil.[15]

William Caxton

[edit]Some boys claimed their names descended from an apprentice William Caxton had in the 1470s.[16] His name changed from De Vile, to DeVille and Deville.[16]

Malayalam root

[edit]While the term "printer's devil" in India may stem from the European legend of Titivillus, another theory is that it might stem from the Malayalam term for "printing error" (achadi pisaku), which is only one change of a Malayalam letter away from "printing devil" (achadi pisachu).[17]

Famous devils

[edit]A number of famous persons served as printer's devils in their youth, including Ambrose Bierce, William Dean Howells, James Printer, Benjamin Franklin, Raymond C. Hoiles, Samuel Fuller, Thomas Jefferson, Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, Warren Harding, Harry Burleigh, Lawrence Tibbett, John Kellogg, Lyndon Johnson, Hoodoo Brown, James Hogg, Geoff Lloyd, Harry Pace, Joseph Lyons, Ezra Meeker, Albert Parsons, Adolph Ochs,[18] and Lázaro Cárdenas. Cole Younger worked as a printer's devil on a prison newspaper while he was incarcerated.[19]

Usage

[edit]United States

[edit]In North America during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, young boys were indentured to printers by their parents, or in the case of orphans, by the municipal or church authorities.[20] More than apprentices in other trades, printer's devils were boys who had expressed an interest in printing.[20] By 1894, American Dictionary of Printing and Bookmaking noted that with the decline of the apprenticeship system in the United States, the term "printer's devil" was going out of use.[2]

India

[edit]The printer's devil is also known in other languages such as Bengali, where it is called Chhapakhanar Bhoot.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ The Oxford Companion to the Book. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 9780198606536.

- ^ a b c Pasko, Wesley Washington (1894). American Dictionary of Printing and Bookmaking. New York: H. Lockwood & Co. p. 136.

- ^ Moxon, Joseph (1683). Mechanick Exercises: Or, the Doctrine of Handiworks, Applied to the Art of Printing.

- ^ Cisco, Michael (2013). Glossator: Practice and Theory of the Commentary. Vol. 8. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 304. ISBN 9781493673933.

- ^ Davis, Robin (2010). "Chapels, Devils, Monks, & Friars: The Irreverent Language of Printing History". Essays by Robin Camille Davis. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Rudwin, Maximilian (1931). The Devil in Legend and Literature. Open Court Publishing Company. pp. 249–250.

- ^ Perry, Timothy P. J. (July 2015). "Early Depictions of the Printing Press". Printing History (18): 27–53.

- ^ Romeo, Nick (6 July 2015). "This Geek Will Put Reporters Out of Business". Daily Beast. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ Pratchett, Terry (2004). Perry, Sheila M. (ed.). Once More with Footnotes: Terry Pratchett. Framingham, Massachusetts: NESFA Press. p. 286. ISBN 9781886778573.

- ^ a b c d Presley, Paula L. (1998). "The Revenge of Titivillus". Books Have Their Own Destiny: Essays in Honor of Robert V. Schnucker. Kirksville, Missouri: Thomas Jefferson University Press. pp. 112, 114–117. ISBN 0-940474-59-X.

- ^ Ellison, Suzanne (17 January 2015). "My old nemesis Titivillus". Lost Art Press. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Johann Fust". Encyclopedia Britannica. 26 October 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Wall-Randell, Sarah (Spring 2008). ""Doctor Faustus" and the Printer's Devil". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 48 (2): 259–260. doi:10.1353/sel.0.0001. JSTOR 40071334. S2CID 149465440.

- ^ "The Princeton Star". open.library.ubc.ca. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "Banner 15 March 1912 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ a b Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. (1998). "Gods, Devils, and Gutenberg: The Eighteenth Century Confronts the Printing Press". Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture. 27 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1353/sec.2010.0189. ISSN 1938-6133.

- ^ a b Bhairav, J. Furcifer; Khanna, Rakesh (2020). Ghosts, Monsters, and Demons of India. Blaft Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 320–321. ISBN 9789380636474.

- ^ Faber, Doris (1963). Printer's Devil to Publisher: Adolph S. Ochs of The New York Times. Julian Messner.

- ^ Baird, Russell N (1967). The Penal Press. Northwestern University Press. p. 28.

- ^ a b Lause, Mark A. (1991). Some Degree of Power: From hired hand to union craftsman in the preindustrial American printing trades, 1778–1815. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781557281852.

Other sources

[edit]- Frank Granger (1997). The Printer's Devil. Retrieved 25 December 2005.

- Rev. E. Cobham Brewer, LL.D. (year unlisted). Character Sketches of Romance, Fiction and the Drama. Retrieved 25 December 2005.

- Pubs and Breweries of the Midlands: Past and Present (year unlisted) The Printer's Devil. Retrieved 25 December 2005.