Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Procolophonidae

View on Wikipedia

| Procolophonids Temporal range:

Middle Permian - Late Triassic

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

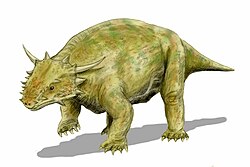

| Skeleton (top) and life restoration (bottom) of Kapes bentoni (Procolophoninae) scale bar = 1cm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Subclass: | †Parareptilia |

| Order: | †Procolophonomorpha |

| Superfamily: | †Procolophonoidea |

| Family: | †Procolophonidae Seeley, 1888 |

| Subgroups and Genera | |

| Synonyms | |

Procolophonidae is an extinct family of small, lizard-like parareptiles known from the Late Permian to Late Triassic that were distributed across Pangaea, having been reported from Europe, North America, China, South Africa, South America, Antarctica and Australia. The most primitive procolophonids were likely insectivorous or omnivorous, more derived members of the clade developed bicusped molars, and were likely herbivorous feeding on high fiber vegetation or durophagous omnivores.[3] Many members of the group are noted for spines projecting from the quadratojugal bone of the skull, which likely served a defensive purpose as well as possibly also for display.[4] At least some taxa were likely fossorial burrowers.[5] While diverse during the Early and Middle Triassic, they had very low diversity during the Late Triassic, and were extinct by the beginning of the Jurassic.[6]

Phylogeny

[edit]The family is defined as all taxa more closely related to Procolophon trigoniceps than to Owenetta rubidgei.[1] Below is a cladogram from Ruta et al. (2011):[7]

| Procolophonidae | |

Below are three cladograms that follow phylogenetic analyses by Butler et al. (2023). Analysis 1: Strict consensus of 760 most parsimonious trees (MPTs):[8]

| Procolophonidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Analysis 2: Single MPT:[8]

| Procolophonidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Analysis 3: Strict consensus of 18 MPTs:[8]

| Procolophonidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ a b Cisneros, J. C. (2008). "Phylogenetic relationships of procolophonid parareptiles with remarks on their geological record". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (3): 345–366. Bibcode:2008JSPal...6..345C. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002350. S2CID 84468714.

- ^ Hans-Dieter Sues and Robert R. Reisz (2008). "Anatomy and Phylogenetic Relationships of Sclerosaurus armatus (Amniota: Parareptilia) from the Buntsandstein (Triassic) of Europe". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1031–1042. Bibcode:2008JVPal..28.1031S. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1031. S2CID 53967912.

- ^ Pinheiro, Felipe L.; Silva-Neves, Eduardo; Da-Rosa, Átila A. S. (August 2021). Ruta, Marcello (ed.). "An early-diverging procolophonid from the lowermost Triassic of South America and the origins of herbivory in Procolophonoidea". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (3): 1601–1612. Bibcode:2021PPal....7.1601P. doi:10.1002/spp2.1355. ISSN 2056-2799. S2CID 233797716. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- ^ Zaher, Marta; Coram, Robert A.; Benton, Michael J. (February 2019). Angielczyk, Kenneth (ed.). "The Middle Triassic procolophonid Kapes bentoni: computed tomography of the skull and skeleton". Papers in Palaeontology. 5 (1): 111–138. Bibcode:2019PPal....5..111Z. doi:10.1002/spp2.1232. hdl:1983/3dd2d71d-a439-404a-997f-758063f40678. S2CID 134058607.

- ^ Botha-Brink, Jennifer; Smith, Roger Malcolm Harris (September 2012). "Palaeobiology of Triassic procolophonids, inferred from bone microstructure". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (6): 419–433. Bibcode:2012CRPal..11..419B. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.03.002.

- ^ MacDougall, Mark J.; Brocklehurst, Neil; Fröbisch, Jörg (2019-03-20). "Species richness and disparity of parareptiles across the end-Permian mass extinction". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1899) 20182572. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2572. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6452079. PMID 30890099.

- ^ Ruta, M.; Cisneros, J. C.; Liebrecht, T.; Tsuji, L. A.; Müller, J. (2011). "Amniotes through major biological crises: Faunal turnover among Parareptiles and the end-Permian mass extinction". Palaeontology. 54 (5): 1117–1137. Bibcode:2011Palgy..54.1117R. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01051.x. S2CID 83693335.

- ^ a b c Butler, R. J.; Meade, L. E.; Cleary, T. J.; McWhirter, K. T.; Brown, E. E.; Kemp, T. S.; Benito, J.; Fraser, N. C. (2023). "Hwiccewyrm trispiculum gen. et sp. nov., a new leptopleuronine procolophonid from the Late Triassic of southwest England". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25316. PMID 37735997.

Sources

[edit]- Lambert, David (2001). Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7894-7935-8.