Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Punt (gridiron football)

View on Wikipedia

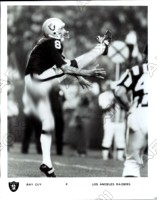

In gridiron football, a punt is a kick performed by dropping the ball from the hands and then kicking the ball before it hits the ground. The most common use of this tactic is to punt the ball downfield to the opposing team, usually on the final down, with the hope of maximizing the distance the opposing team must advance in order to score. The result of a typical punt, barring any penalties or extraordinary circumstances, is a first down for the receiving team. A punt is not to be confused with a drop kick, a kick after the ball hits the ground, now rare in both American and Canadian football.

The type of punt leads to different motion of the football. Alex Moffat invented the now-common spiral punt, as opposed to end-over-end.

Description

[edit]A punt in gridiron football is a kick performed by dropping the ball from the hands and then kicking the ball before it hits the ground. In football, the offense has a limited number of downs, or plays, in which to move the ball at least ten yards. The team in possession of the ball will typically punt the ball to the opposing team when it is on its final down (fourth down in American football, third down in Canadian football), does not want to risk a turnover on downs by not gaining enough yardage to make a first down, and does not believe it is in range for a successful field goal. The purpose of the punt is for the team in possession, or "kicking team", to move the ball as far as possible towards the opponent's end zone; this maximizes the distance the receiving team must advance the ball in order to score a touchdown upon taking possession.

A punt play involves the kicking team lining up at the line of scrimmage with the kicker, or punter, typically lined up about 15 yards behind the center. In American football, the end zone is only ten yards deep and as such this distance must be shortened if the kicker's normal position would be on or beyond the end line. In Canadian football the end zone is twenty yards deep and therefore sufficiently large for the punter to take his usual position in any situation. However, Canadian rules also give scored-on teams more advantageous field position following a safety, so Canadian football punters will often choose to concede two points instead of punting from the end zone.

The receiving team lines up with one or two players downfield to catch the ball. The center makes a long snap to the kicker who then drops the ball and kicks it before it hits the ground. The player who catches the ball is then entitled to attempt to advance the ball.

The result of a typical punt, barring any penalties or extraordinary circumstances, is a first down for the receiving team at the spot where:

- the receiver or subsequent receiving team ball carrier is downed or goes out of bounds;

- the ball crosses out of bounds, whether in flight or after touching the ground;

- there is "illegal touching", defined as when a player from the kicking team is the first player to touch the ball after it has been punted beyond the line of scrimmage; or

- a ball which is allowed to land comes to rest in-bounds without being touched (American football only).

Other possible results include the punt being blocked behind the line of scrimmage, and the ball being touched, but not caught or possessed, downfield by the receiving team. In both cases the ball is then "free" and "live" and will belong to whichever team recovers it.

Rules

[edit]

Common to American and Canadian football

[edit]- If the kicked ball fails to cross the line of scrimmage, it may be picked up and advanced by either team. However, if it is picked up by the kicking team, the play is treated as any other play from scrimmage; i.e., if it is the team's final down, it must advance the ball beyond the first down marker in order to avoid a turnover on downs. There are two ways a punt can fail to cross the line of scrimmage: a blocked kick, in which the opposing team obstructs the path of the punt shortly after it leaves the punter's foot; and a shank, in which the punter fails to advance the kick beyond the line of scrimmage on his own (usually erroneous) action. If a punt crosses the plane above the line of scrimmage at any point during the punt, it is treated as such and the kicking team may not advance it, even if the ball moves on its own volition (either due to a headwind or errant bounce) back behind the line.

- Deliberate, targeted punting to another player on the kicking team behind the line of scrimmage has some strategic advantages (for example, an offensive lineman can receive a forward punt but is not eligible to receive a screen pass) but, because of some disadvantages (any errant kick that crosses the line of scrimmage would result in lost possession), is extremely rare as a strategy.

- The official rules regulate when and how the receiving team may hit the kicker before, during, and after the kick.

- If the receiving team drops the ball or touches the ball beyond the line of scrimmage without catching it then it is considered a live ball and may be recovered by either team. If the receiving team never had full possession, it is considered to be a muffed punt rather than a fumble. However, the receiving player must be actively pursuing the ball. If the receiving player is blocked into the ball, it is not considered "touching" the ball.

- A field goal cannot be scored on a punt kick.

- By contrast, the now very rarely attempted drop kick can be used to score either field goals or extra points in both American and Canadian football.

American football

[edit]- The player attempting to catch the kicked ball may attempt a fair catch. If caught, the ball becomes dead and the receiving team gets the ball at the spot of the catch.

- A touchback may be called if any of the following occur: (1) The kicked ball lands in the receiving team's end zone without first touching any player, whether as a direct result of the kick or a bounce. (2) The receiving team catches the ball in its own end zone and downs it before advancing the ball out of the end zone. (In high school football, the ball automatically becomes dead when it crosses the goal line and cannot be returned out of the end zone, except in Texas, which bases its high school rules on the NCAA rule set.) (3) The ball enters then exits the end zone behind the goal line. After a touchback, the receiving team gets the ball at its own 20-yard line except in the current XFL, which spots the ball on the receiving team's 35. The XFL also spots the ball on the 35 if a punt goes out of bounds between the receiving team's 35 and its own end zone.

- If a player from the kicking team is the first to touch the ball after it crosses the line of scrimmage, "illegal touching" is called and the receiving team gains possession at the spot where the illegal touching occurred. This is often not considered to be detrimental to the kicking team; for example, it is common for a player on the kicking team to deliberately touch the ball near the goal line before it enters the end zone to prevent a touchback. Since there is no further yardage penalty awarded, the kicking team is often said to have "downed the ball" when this occurs (and the NFL does not count it as an official penalty). While the ball is not automatically dead upon an illegal touch, and can be advanced by the receiving team (who would then have the choice of accepting the result of the play or taking the ball at the spot of the illegal touch), this rarely happens in practice, as illegal touching typically occurs when members of the kicking team are closer to the ball than members of the receiving team. In the NFL, this is referred to as "first touching," and is considered a "violation," and cannot offset a foul by the receiving team.[1] Moreover, kicking team players are allowed to bat the ball back into the field of play so long as they have not touched the goal line or end zone, even if their bodies enter the air above the end zone; in such cases, the ball is spotted from where the player jumped or the 1-yard line, whichever is farther from the goal line.

- The length of the punt, referred to as punting yards or gross punting yards, is measured from the line of scrimmage (not the spot where the punter punts) to whichever of the following points applies: (1) the spot that a punt is caught; (2) the spot that a punt goes out of bounds; (3) the spot that a punt is declared dead because of illegal touching; or (4) the goal line, for punts that are ruled touchbacks.

- The net punting yardage is taken by calculating the total punting yardage and subtracting any yardage earned by the receiving team on returns, and subtracting 20 yards for each touchback.

- Under no circumstance can the kicking team score points as the direct result of a punt. (It can score indirectly if the receiving team loses possession of the ball or runs back into its own end zone and gets tackled.)

Canadian football

[edit]

- The kicker and any players behind him at the time of the kick are considered "onside"; any other players on the kicking team are considered "offside". This is the same rule that makes all players "onside" on a kickoff since they are behind the ball once kicked. A player who is onside may recover the kicked ball, while a player who is offside may not be the first to touch the kicked ball and is required to remain at least 5 yards from an opposing player attempting to catch the ball. Violations of these restrictions on an offside player are called "no yards" infractions, with various penalties associated with them.

- The ball remains in play if it enters the goal area (end zone) until it is downed by a player on either team or goes out of bounds:

- If a member of the receiving team downs it in the goal area or the ball goes out of bounds before being brought back into the field of play, a single is awarded to the kicking team and the receiving team gains possession at their own 35-yard line.

- If an onside player downs the ball in the goal area, the kicking team is awarded a touchdown.

- If an offside player downs the ball in the goal area, the receiving team gains possession after a "no yards" penalty is applied from their own 10-yard line.

- If the ball strikes the goalpost assembly while in flight the receiving team gains possession at their own 25-yard line.

- The length of the punt is measured from the line of scrimmage to the spot of the catch or the point where the kick goes out of bounds. The punt return is measured independently, though the value of the punt to the kicking team is determined by distance from the line of scrimmage to the end of the return.

- Canadian rules also allow a punt when the punter is not behind the line of scrimmage, which is not permitted in American rules. This tactic (termed an "open-field kick" in the rule book) is similar to rugby and in the modern game is usually reserved for last-second desperation: for example, a player, after receiving a forward pass with no time left on the clock and with no hope of evading tacklers, may punt the ball in the hope that it will score a single or be recovered by an onside teammate. After recovering a ball kicked by the other team a player can also punt out of his own end zone in order to avoid a single. On at least two occasions in the CFL, the last play of the game was a missed field goal attempt followed by three punts, as the teams alternately tried to avoid a single and score a single.[2][3][4][5]

Types of punts

[edit]The type of punt leads to different motion of the football.

End-over-end punt

[edit]Spiral punt

[edit]Alex Moffat is generally recognized as the creator of the spiral punt, having developed it during his time as a college athlete in the early 1880s.[6] It is the longest type of punt kick. In flight, the ball spins about its long axis, instead of end over end (like a drop punt) or not at all (like a regular punt kick). This makes the flight of the ball more aerodynamic, and the pointy ends of gridiron footballs mitigate the difficulty to catch.

Pooch punt

[edit]Teams may line up in a normal offensive formation and have the quarterback perform a pooch punt, also known as a quick kick. This usually happens in situations where the offense is in a 4th and long situation in their opponent's territory, but are too close to the end zone for a traditional punt and (depending on weather conditions) too far for a field goal try—a situation also known as the dead zone. Like fake punt attempts, these are rarely tried, although Randall Cunningham, Tom Brady, Matt Cassel and Ben Roethlisberger have successfully executed pooch punts in the modern NFL era.[7][8][9] Some pooch punts occur on third down and long situations in American football to fool the defense, which is typically not prepared to return a punt on third down.

Fake punts

[edit]On very rare occasions, a punting team will elect to attempt a "fake punt"—line up in punt formation and begin the process as normal, but instead do one of the following:[citation needed]

- The punter may choose to run with the ball.

- The ball may be snapped to the upback, who then runs with the ball.

- The punter (or another back, who is standing nearby) may decide to pass to a pre-designated receiver.

- The ball may be snapped to the upback, who then passes the ball to a receiver.

Although teams sometimes use fake punts to exploit a weakness in the opposing team's defense, a fake punt is very rare, and often used in desperate situations, such as to keep a drive alive when a team is behind and needs to catch up quickly, or to spark an offense in a game where the defense dominates. The high risk of "fake punts", and the need to maintain an element of surprise when the play is actually called, explains why this play is seldom seen. Fake punts are more likely to occur when there is short yardage remaining to secure a first down, or the line of scrimmage is inside the opponent's territory.[citation needed]

One of the most famous fake punts was by New York Giants linebacker Gary Reasons during the 1990 NFC Championship Game against the San Francisco 49ers, in which he rushed for 30 yards on a fourth down conversion via a direct snap to him instead of the punter, Sean Landeta, which was a critical difference in a 15–13 victory. The Giants went on to win Super Bowl XXV.[citation needed]

Rugby-style punt

[edit]A rugby-style punt is done with a running start (usually to the left or right) before punting while remaining behind the line of scrimmage.[10]

Punting records

[edit]- The longest punt in North American pro football history is a 108-yarder by Zenon Andrusyshyn of the Canadian Football League's Toronto Argonauts (at Edmonton, October 23, 1977).[11] This record was also tied by Christopher Milo of the Saskatchewan Roughriders on October 29, 2011, at a home game at Mosaic Stadium at Taylor Field in Regina, during which winds gusted above 35 miles per hour (56 km/h).[citation needed] Taylor Field, which has since been replaced and demolished, also remains the site of the three longest field goals in CFL history and was one of the windiest fields in professional football.[citation needed]

- The longest punt in NFL/AFL play was a 98-yarder by Steve O'Neal of the New York Jets in an American Football League regular season loss to the Denver Broncos at Mile High Stadium on September 21, 1969.[12]

- Jeff Feagles is the all-time NFL career punts and punt yards leader with 1,713 punts and 71,211 punt yards over 352 games.[13]

- Bob Cameron is the all-time CFL career punts and punt yards leader with 3,129 punts and 134,301 punt yards over 394 games.[14]

- Shane Lechler holds the NFL record for career punting average with 47.6 yards per punt.[15]

- Ryan Stonehouse holds the single-season record for yards per punt with a 53.1 yards per punt average in 2022 (90 punts for 4,779 yards). This broke an 82-year-old record held by Sammy Baugh who averaged 51.4 yards per punt in 1940 (35 punts for 1,799 yards).[16]

- The record for college football is held by the University of Nevada's Pat Brady, who booted the longest possible punt on a 100-yard field at 99 yards against Loyola University on October 28, 1950.[17]

- Joe Theismann punted for one yard against the Chicago Bears in 1985.[18][19]

Return

[edit]A punt return is one of the receiving team's options to respond to a punt. A player positioned about 35–45 yards from the line of scrimmage (usually a wide receiver or return specialist) will attempt to catch or pick up the ball after it is punted by the opposing team's punter. He then attempts to carry the ball as far as possible back in the direction of the line of scrimmage, without being tackled or running out of bounds. He may also lateral the ball to teammates in order to keep the play alive should he expect to be tackled or go out of bounds. The punting team may employ a "directional punting" strategy. This strategy has a punter place the ball in a way that pins returners against the sideline deep on their side of the field, minimizing their potential to have a big return.[20][21]

DeSean Jackson, then playing for the Philadelphia Eagles in the "Miracle at the New Meadowlands", is the only NFL player to return a punt for a game-winning touchdown on the final play of regulation.[22] The NFL record holder for the number of punt returns for a touchdown in a career is Devin Hester with 14. The CFL career record holder for most punt returns for a touchdown in a career is Gizmo Williams with 26.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2012 OFFICIAL PLAYING RULES AND CASEBOOK OF THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE" (PDF). static.nfl.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-23. Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- ^ "Crazy ending lifts Alouettes over Argonauts". TSN.ca. The Canadian Press. 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- ^ blackknight101066 (30 October 2010). "Crazy Argonauts – Alouettes CFL ending.mp4". Archived from the original on 2021-11-18 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ CFLfan#31 (19 September 2015). "SC: Top 10 Crazy CFL Moments". Archived from the original on 2021-11-18 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Nov. 19, 1972 Abendschan boots Blue in stadium's greatest game". winnipegfreepress.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016.

- ^ David M. Nelson. The Anatomy of a Game: Football, the Rules, and the Men who Made the Game. p. 53.

- ^ "Randall Cunningham Past Stats, Statistics, History, and Awards – databaseFootball.com". databasefootball.com. Archived from the original on 2009-01-14.

- ^ "Let's talk about Brady's punt". go.com. 15 January 2012. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "Ben Roethlisberger Past Stats, Statistics, History, and Awards – databaseFootball.com". databasefootball.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-31.

- ^ First Sporting Production (2015-10-17), Aussie punter Blake O'Neill's Punts 80 yard Rugby Style Punt, archived from the original on 2017-09-16, retrieved 2017-09-07

- ^ "Regular Season All-Time Records – Individual Records – Punting" Archived 2009-09-03 at the Wayback Machine. Canadian Football League. (The CFL's field is ten yards longer than the NFL's.)

- ^ "Bouncing ... bouncing – Pro Football Hall of Fame Official Site". profootballhof.com. Archived from the original on 2009-02-05. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- ^ "NFL Punting Leaders (All Time)". PlayerFilter.com.

- ^ Regular Season All-Time Records Archived 2010-07-04 at the Wayback Machine Canadian Football League

- ^ "NFL Yards per Punt Career Leaders (since 1939)". Pro-Football-Reference. Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "NFL Yards per Punt Single-Season Leaders (since 1939)". Pro-Football-Reference. Archived from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ National Football Foundation

- ^ Joe Theismann NFL & AFL Statistics Archived 2018-04-24 at the Wayback Machine. pro-football-reference.com. Pro Football Reference.

- ^ UPI (September 30, 1985). Bears Show Redskins a Team on the Rise Archived 2016-05-17 at the Wayback Machine. Lodi News-Sentinel, p. 17.

- ^ Vrentas, Jenny (September 18, 2009). "For Jeff Feagles, directional punting becomes a fine science". NJ.com. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Erickson, Joel A. (August 24, 2022). "Source: Colts are signing former Bills punter Matt Haack after losing Rigoberto Sanchez". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Frank, Reuben (December 19, 2010). "Miracle at the Meadowlands III: Eagles 38, Giants 31". CSN Philly. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ^ "Henry "Gizmo" Williams". Canadian Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 2023-02-20. Retrieved 2023-02-20.

External links

[edit] Media related to Punts (American football) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Punts (American football) at Wikimedia Commons

Punt (gridiron football)

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Purpose

In gridiron football, a punt is a kick executed by releasing the ball from the hands and contacting it with the foot before it touches the ground.[11] This distinguishes it from other kicks, such as drop kicks, and is a key special teams play. In American football, punts typically occur on fourth down, the final opportunity in a series of four downs to advance at least 10 yards, while in Canadian football, they are commonly executed on third down within the three-down system requiring 10 yards for a first down.[12][10] The primary purpose of a punt is to voluntarily relinquish possession to the opposing team while optimizing field position, forcing the return team to begin their offensive drive deep in their own territory and providing a territorial advantage to the punting team's defense.[13] This strategy minimizes the risk of a turnover on downs, where failing to gain the required yardage would award the ball to the opponent at the spot of the line to gain, potentially in advantageous position for the defense. In contrast to attempting a field goal—which aims to score three points but carries the risk of a miss allowing a short return—punting prioritizes defensive positioning over potential points, especially when the kicking distance exceeds reliable range. Punts also play a role in game management, such as at the end of a half to consume remaining time without risking further offensive plays.[14][15] The frequency and strategic importance of punts vary across levels of play. In professional American football, such as the NFL, teams averaged approximately 3.0 punts per game per team in the 2024 season, continuing a decline from about 4.8 in 2017 driven by analytics favoring more aggressive fourth-down attempts to retain possession.[16][17][18] College football sees a similar but slightly higher rate, around 3.8 punts per team per game, reflecting a balance between aggression and conservatism amid varying talent levels. In high school football, punts remain more prevalent than in professional levels, as coaches emphasize field position control due to developmental skill gaps and risk-averse decision-making.[19]Historical Development

The origins of punting in gridiron football trace back to the mid-19th century, when the sport emerged from rugby influences in the United States as a running and kicking game without forward passing. In these early forms, punting served as a primary offensive strategy to advance the ball downfield, often executed on any down to gain territorial advantage or force turnovers, reflecting the rugby heritage where kicking was central to play progression.[20][21] A pivotal innovation occurred in the 1880s when Princeton University player Alex Moffat developed the spiral punt, which imparted a stabilizing spin on the ball to enhance distance and accuracy compared to previous end-over-end kicks. This technique revolutionized punting by allowing for greater hang time and roll, making it a more reliable tool for field position battles in intercollegiate games. Moffat's contribution, refined during Princeton's competitive era against rivals like Yale, marked a shift toward specialized kicking skills in American football.[22] The role of punting evolved significantly with rule changes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Walter Camp introduced the downs system in 1882, requiring teams to gain five yards in three attempts (later adjusted to 10 yards in four downs by 1912), which initially encouraged punting on second or third downs to avoid turnovers when yardage was short. The legalization of the forward pass in 1906, prompted by concerns over player safety and game brutality, further diminished punting's status as a core offensive play, transforming it into a primarily defensive fourth-down tactic to maximize field position and pin opponents deep. These standardizations, overseen by Camp and the Intercollegiate Football Rules Committee, professionalized the sport and relegated punting to situational use.[23][21] In the modern era, the influx of Australian Rules football players into the NFL beginning in the 1990s introduced rugby-style drop punts, characterized by a pointed toe contact for tighter spirals and better control. Darren Bennett, who joined the San Diego Chargers in 1993 after a career in Australian Rules, exemplified this shift by popularizing the technique, which improved directional precision and reduced touchbacks. This influence led to a cadre of Australian punters, including Ben Graham and Mat McBriar, and contributed to rising league-wide punt averages, from approximately 41 yards in the 1980s to over 43 yards by the late 1990s, enhancing strategic depth in special teams.[24] Key milestones in punting's development include the adoption of protective gear in the 1920s, such as leather helmets and padded nose guards, which provided punters—often exposed during kick setups—with basic safeguards against collisions amid increasing game speeds. By the 1930s, the NFL began systematic statistical tracking of punts, starting with incomplete seasonal data in 1933 and formalizing complete records in 1939, enabling analysis of averages and yardage to inform player evaluation and strategy. These advancements underscored punting's transition from ad hoc rugby remnant to a data-driven component of professional football.[25][26]Rules

Common Rules

In gridiron football, a punt begins with a snap from the center to the punter or an upback, after which the punter drops and kicks the ball before it touches the ground. The receiving team takes possession at the spot where the ball is first secured by a player or downed, and may advance it further if recovered while in motion.[27][28] The ball remains live from the moment of the legal kick until it is downed, goes out of bounds, or results in a score, such as a safety if the kicking team forces it into their own end zone. This live status allows the receiving team to advance the ball if they secure possession before it becomes dead.[27][28] Common penalties during a punt include illegal procedure, such as having too many players on the line of scrimmage or ineligible players downfield, which typically results in a five-yard loss from the previous spot. Roughing the punter, involving unnecessary contact with the kicker's plant leg or body, incurs a 15-yard penalty and an automatic first down to the receiving team in American football, while a similar infraction in Canadian football draws a 15-yard penalty. Interference with the opportunity to catch the kicked ball, such as by the kicking team blocking illegally downfield, leads to a 15-yard penalty from the spot of the foul, with the receiving team awarded a fair catch option.[27][28] Unlike a drop kick, which can be used for field goal attempts, a punt snap does not permit a field goal try, as the rules distinguish punts as forward scrimmage kicks intended to advance the ball downfield rather than through the uprights. League-specific variations, such as end zone dimensions, may influence outcomes like touchbacks but do not alter these core procedures.[27][28] Punt rules have remained stable with no major punt-specific alterations implemented in the 2024 or 2025 seasons in either league, in contrast to recent modifications to kickoff procedures.[27][28]American Football Specifics

In American football leagues such as the NFL, NCAA, and NFHS, the fair catch rule permits a member of the receiving team to signal intent to catch a punt without interference, resulting in the ball being dead at the spot of the catch and possession awarded there without advancement. The signal consists of extending one arm above the head and waving it from side to side while the ball is in the air, applicable only to scrimmage kicks that have crossed the line of scrimmage or free kicks that have not touched the ground in flight.[27] Fair catch interference, which carries a 15-yard penalty from the spot of the foul and automatic first down, cannot occur in the end zone because a fair catch signal there would effectively result in a touchback rather than protected possession.[27] A touchback on a punt occurs when the ball crosses the goal line and becomes dead in the end zone without being advanced out, or when it is downed or goes out of bounds there; in all American football levels, the receiving team begins the next series at its own 20-yard line.[27] If a punt goes out of bounds untouched between the goal lines, the receiving team takes possession at the spot where the ball exited the field, with no penalty enforced unless the kicking team illegally touches the ball prior to it going out.[27] Punts in American football are exclusively attempted on fourth down, the final opportunity to gain a first down before possession turns over to the opponent, distinguishing the play from field goal attempts which may occur on any down but are more common on fourth.[27] Quick kicks—punts executed on first, second, or third down for surprise field position advantage—were a standard tactic in the early 20th century but have become exceedingly rare in modern play due to advanced offensive strategies and risk assessment. In the NFL, the punter receives enhanced protection equivalent to that of a passer during fake punt attempts; if the punter receives the long snap and simulates or attempts a forward pass, contact violating roughing the passer rules—such as striking the head or neck area—results in a 15-yard penalty and automatic first down.[27] College football under NCAA rules includes specific variations like the hands-to-the-face foul during punt returns, where a defender using hands or arms to ward off a blocker in a manner that contacts the facemask or helmet incurs a 15-yard penalty, emphasizing player safety in blocking schemes. High school football, governed by NFHS rules, features simplified fair catch signal enforcement, where an invalid or late signal still results in a five-yard penalty from the spot but without the stricter NFL scrutiny on intent, and many states lack instant replay review for punt plays, limiting on-field calls to human officials.Canadian Football Specifics

In Canadian football, governed by the three-down system, teams must advance the ball at least 10 yards in three consecutive plays from scrimmage or relinquish possession.[28] This structure frequently results in punts occurring on third down, as offenses often opt to kick away rather than risk turning the ball over on downs near the first-down marker, thereby increasing the overall frequency of punting compared to four-down systems.[29] A distinctive scoring element in Canadian football is the single point, commonly known as the rouge, awarded to the kicking team when a punt enters the opponent's end zone and becomes dead there without being returned to the field of play.[28] The 20-yard depth of the end zone facilitates this outcome, as the ball need only travel into and remain in the goal area—either by rolling out the back or being downed—to yield the point, after which the receiving team begins its next series from its own 40-yard line between the hash marks.[3] Downed balls in the end zone similarly result in a single point unless successfully returned out.[28] Regarding recovery options, Canadian rules permit the kicking team to attempt an onside punt, where a designated onside player—positioned behind the ball at the moment of the kick—may legally recover the live ball after it crosses the line of scrimmage, potentially regaining possession for a first down.[30] If the punt fails to cross the line of scrimmage, the kicking team can also recover it as a live ball without penalty.[28] However, an offside player from the kicking team—any teammate ahead of the ball at the kick—who touches it before it reaches the receiving team incurs no penalty if untouched by opponents, but possession is awarded to the receiving team at the point of recovery or the 15-yard line if in the goal area; interference by offside players results in a 15-yard penalty.[10] Unlike some other variants, Canadian football lacks a fair catch rule for punts, requiring returners to either advance the ball or risk a tackle, with the kicking team obligated to provide a five-yard buffer zone around the returner to prevent contact during possession attempts.[28] This encourages dynamic returns but heightens the strategic value of pinning opponents deep. The Canadian field's dimensions—110 yards long and 65 yards wide, with 20-yard end zones—distinctly influence punting strategies and distances, allowing for longer kicks due to the extended length and broader width, which provides more room for directional placement without touchbacks.[28] There is no designated touchback line equivalent to other codes; instead, any punt entering the end zone without return defaults to a rouge, and subsequent plays originate from the 40-yard line rather than a hash mark adjustment.[3] Note that rule changes announced in September 2025 will modify the rouge for unreturned punts starting in 2026, limiting singles to instances where the returner is tackled in the end zone or concedes, while field dimensions will shorten to 100 yards with 15-yard end zones in 2027.[31]Execution

Player Roles and Setup

In a standard punt formation in American football, the punter, a specialist responsible for executing the kick, positions themselves approximately 15 yards behind the line of scrimmage to allow time for the ball to be snapped and dropped for the kick.[32] The long snapper, often a dedicated player distinct from the regular center due to the specialized 15-yard snap required for punts, delivers the ball directly to the punter's hands with precision to prevent fumbles.[33] This snap must occur within about 0.8 seconds, contributing to an overall snap-to-kick window of 1.8 to 2.0 seconds in the NFL, which is critical for timing and protection.[34] The protection unit consists of five to seven blockers on the line of scrimmage, including the long snapper flanked by two guards and two tackles, who form a core to shield the punter from rushers.[35] An upback, or personal protector, aligns 5 to 7 yards behind the line of scrimmage, serving as the final barrier against blockers and occasionally catching the snap if the punter is in motion.[36] Two gunners, typically speedy defensive backs or wide receivers, line up wide outside the protection unit on the line of scrimmage, focusing solely on downfield coverage rather than blocking, to pursue and tackle the returner.[35] The remaining coverage team, comprising 9 to 10 players including the gunners and non-linemen, rushes downfield immediately after the snap to limit return yardage. In professional football like the NFL, formations emphasize robust protection with up to seven blockers due to rules restricting most linemen from advancing until the ball is kicked, allowing more potential rushers from the receiving team.[37] College football setups often feature fewer dedicated rushers and more aggressive coverage schemes, as linemen can advance unrestricted, leading to tighter protections with 5 blockers and quicker gunner releases.[37] Rugby-style punts adapt the standard setup by having the punter receive the snap while stationary but then take a short running start toward the ball before dropping and kicking it, which requires the same protection line and upback but enhances directional control without altering the overall formation.[38] Punters rely on specialized cleats for grip on the plant foot during the drop and swing, ensuring stability on varied field conditions within the tight 1.5- to 2-second execution window.[34]Kicking Mechanics

The punting process begins with the punter receiving the snap from the center, typically at belt to chest height, allowing 1.1 to 1.5 seconds for preparation depending on the level of play.[39] The punter then grips the ball with a three-quarters underneath hold, positioning the laces away from the kicking foot to minimize wobble upon contact, and drops it nose-down at a 5- to 10-degree angle toward the instep.[39] The plant foot is positioned beside the ball in a square or staggered stance, ensuring balance and alignment straight toward the target line without overstriding.[39] Finally, the kicking leg swings through the ball's center in a whipping motion, incorporating torso rotation to generate power, with the foot releasing at approximately 180 degrees post-contact for directional control.[39] Biomechanically, effective punting relies on hip drive during the leg swing to maximize velocity, followed by a full follow-through to optimize both height and distance.[40] This sequence—encompassing approach, backswing, downswing, leg swing, and follow-through—transfers kinetic energy efficiently from the torso through the lower body.[41] In the National Football League (NFL), these mechanics contribute to an average gross punt distance of 47.4 yards and hang time of about 4.3 seconds, establishing key context for field position advantage.[42][43] Several factors influence punt quality, including ball grip and drop technique, where a consistent drop ensures centered contact, unlike held kicks in placekicking.[39] Wind requires adjustments such as altering the drop angle or aiming slightly into the breeze to maintain trajectory.[44] Surface type also plays a role; artificial turf offers consistent traction for the plant foot compared to natural grass, which can vary in firmness and affect stability during the swing.[45] Training emphasizes drills for consistency, such as wall kicks to refine drop precision and contact point without full momentum.[46] Australian techniques, popularized through programs like Prokick Australia, influence modern punting by promoting a rollout drop for spiral stability, adopted by many NFL specialists.[47] Common errors include shanked punts, resulting from low or off-center contact—often due to a flawed drop or leaning away from the ball—leading to significantly reduced distance and poor hang time.[39][46]Variations and Strategies

Conventional Punt Types

The conventional punt types in gridiron football primarily emphasize distance, control, and field position management through standard kicking techniques. These include the spiral punt, end-over-end punt, and directional punting, each tailored to specific game situations while relying on the basic drop-kick mechanics of releasing the ball from the punter's hands and striking it before it touches the ground.[48] The spiral punt, the most common conventional style in professional and collegiate play, involves striking the ball's center to impart a tight rotation along its long axis, similar to a forward pass, resulting in a straight, low-trajectory flight path that maximizes distance.[49] This technique, invented by Alex Moffat in 1881 during his time as a Princeton University player, revolutionized punting by replacing the earlier end-over-end method and enabling kicks of 60 yards or more under optimal conditions.[50] The spiral reduces air resistance through gyroscopic stabilization, allowing for greater accuracy and range compared to non-spinning kicks.[51] However, its predictable flight can facilitate returns if the coverage team fails to contain the receiver, as the ball is easier to track and catch.[8] In contrast, the end-over-end punt features a rotational flip where the ball tumbles nose-over-tail, producing a higher arc with shorter hang time, which is particularly effective in windy conditions to minimize drift and maintain control.[52] This style, predating the spiral and rooted in early football practices, creates a wobbling motion that acts as a natural deterrent to returns by making the ball harder to field cleanly, though it sacrifices some distance for enhanced safety and placement precision.[53] Punters often employ it when prioritizing avoidance of big returns over maximum yardage, such as near midfield or in adverse weather.[8] Directional punting integrates these rotational styles by aiming the kick toward the sidelines to pin the receiving team against the boundary, forcing short fields and limiting return options through reduced lanes for the returner.[54] This strategy focuses on "inside-the-20" placements—kicks landing within 20 yards of the goal line—to flip field position advantageously, often using a slight body angle adjustment during the drop to curve or steer the ball.[55] While spirals excel in length but risk longer returns, end-over-end punts offer safer handling at the cost of fewer yards, making directional applications a balanced choice for controlling opponent starting position.[56] In the 2025 NFL season, Cincinnati Bengals punter Ryan Rehkow exemplified effective spiral punting, leading the league with a gross average of 52.8 yards per punt across 38 attempts, including several 60-plus yarders that contributed to strong net field position gains.[57] Such performances underscore how conventional types remain foundational to special teams strategy, balancing distance with tactical placement.Specialized and Deceptive Punts

In gridiron football, specialized punts are employed in targeted scenarios to maximize field position advantage or exploit defensive alignments, often prioritizing precision over distance. The pooch punt, a high-arcing kick typically covering 20 to 40 yards, is executed by either the punter or quarterback to drop the ball into the "coffin corner"—the area near the sideline and goal line—allowing it to bounce out of bounds without entering the end zone for a touchback.[58] This technique deceives return specialists by limiting their space and forcing fair catches or short returns inside the opponent's 10-yard line.[59] The rugby-style punt, distinct from traditional drop punts, involves the kicker taking a running start and dropping the ball for a soccer-like strike without a snap from center, enabling quicker execution in time-sensitive situations. In Canadian Football League (CFL) play, this variant is particularly valued for emergencies, such as avoiding blocked kicks or rapidly advancing the ball after a turnover, as its momentum can generate roll or directional control on the wider field.[60] Deceptive punts introduce elements of surprise to disrupt return coverage. Fake punts, where the team opts for a run or pass instead of kicking, occur infrequently due to their high risk, with overall league-wide attempts comprising less than 1% of punt formations in the NFL, though success rates exceed 50% on short-yardage conversions like fourth-and-1 to 3. A notable example is linebacker Gary Reasons' 30-yard fake punt run in the 1990 NFC Championship Game, which set up a crucial field goal for the New York Giants against the San Francisco 49ers.[61][62][63] Such plays are more prevalent in college football, where aggressive fourth-down strategies lead to higher fake punt frequencies compared to the NFL's conservative approach.[64] Mis-direction techniques further enhance deception through ball flight manipulation. Baltimore Ravens punter Sam Koch pioneered "slice" punts in the 2010s, intentionally misaligning his body to feign a directional kick—such as angling toward the right sideline—before slicing across the ball to curve it oppositely, often landing it inside the 20-yard line while wrong-footing returners.[65] This innovation, part of Koch's repertoire of over 10 specialized kicks, has influenced modern punting by emphasizing variability to counter elite returners.[66]Returns

Return Rules

In American football, the ball becomes live upon the first touch by the receiving team during a punt, allowing them to recover and advance it from the spot of recovery, the point where it goes out of bounds, or the location where it is downed by the receiving team.[27] If the kicking team first touches the ball beyond the neutral zone, the receiving team may elect to take possession at that spot rather than where it is recovered.[27] A key protection for the receiving team is the fair catch rule, where a player signals intent by extending one arm above the helmet and waving it side to side while the kick is in flight before catching an airborne punt that has crossed the line of scrimmage and not touched the ground; this declares the ball dead upon catch, prevents any contact by the kicking team, and stops the game clock without allowing advancement.[27] Interference with a fair catch signal, such as contact before or after the catch, results in a 15-yard penalty from the spot of the foul and an automatic first down for the receiving team; flagrant interference may lead to disqualification.[27] Blocking during punt returns is restricted to prevent dangerous play: the receiving team may not initiate blocks until the ball is touched in the field of play, and all blocks must comply with offensive holding rules, prohibiting blocks below the waist or in the back.[27] Clipping, defined as blocking an opponent from behind below the waist, incurs a 15-yard penalty from the spot of the foul and potential disqualification if deemed unnecessary roughness; taunting by either team during returns, such as excessive celebrations, also draws a 15-yard unsportsmanlike conduct penalty.[27] In 2025, no major alterations were made to core punt return rules, though instant replay was expanded to assist officials in reviewing objective elements of plays, including potential interference fouls, if clear and obvious video evidence exists to overturn on-field calls.[67] Canadian football differs notably, with no fair catch equivalent; instead, a five-yard "halo" or no-touch zone protects the returner, requiring kicking team players to remain at least five yards away from any receiver attempting to catch or recover a punt until the ball is touched, enforced by a 15-yard "no yards" penalty from the point of interference.[28] For the receiving team in the CFL, the ball is live on first touch, permitting advance from the recovery spot, out-of-bounds location, or downed position, but special end-zone rules apply: if a punt enters the goal area and is downed there by the receiving team or not advanced out, the kicking team scores a single point (rouge), whereas advancing it out of the end zone allows the receiving team to retain possession for the return.[28] Blocking rules mirror American football's emphasis on safety, banning blocks below the waist or from behind during returns, with clipping penalized at 15 yards as unnecessary roughness; the 2025 season saw no significant changes to these provisions, maintaining the traditional framework ahead of proposed rouge modifications in 2026.[28]Return Techniques

Returners begin by securing the punt through proper catching techniques, positioning their body with feet shoulder-width apart and knees slightly bent to maintain balance and enable quick directional changes after the catch.[68] This stance allows the returner to track the ball's spiral while shielding it from defenders, tucking it securely against the body with both hands to prevent bobbles.[69] If opting not to advance, the returner signals a fair catch by extending one arm above the helmet and waving it side to side while the kick is in flight, ensuring no interference from the coverage team and retaining possession at the spot of the catch.[70] Once secured, advancing involves weaving through the coverage unit using vision to identify gaps, accelerating with short, explosive bursts to evade tacklers, often exemplified by elite returners like Devin Hester, who scored 14 punt return touchdowns in his NFL career through such speed and agility.[71] The return team's blockers play a crucial role in creating these lanes, employing schemes like wedges—where multiple players converge to wall off defenders—or arrows, directing blocks toward specific coverage threats to spring the returner forward.[72] To counter the punting team's gunners—fast downfield rushers—blockers often use double-team assignments, with one player jamming the release and another riding the gunner out of the play to protect the return path.[73] In the Canadian Football League (CFL), return techniques emphasize escaping the end zone to avoid conceding a single point (rouge), where returners field deep punts and advance laterally or forward to midfield for optimal field position, prioritizing quick lateral cuts over straight-line sprints due to the larger field dimensions.[74] Advanced skills in both leagues include burst acceleration post-catch, as seen in Hester's style, but CFL returners often focus on end-zone avoidance maneuvers to neutralize the rouge threat.[75] These techniques carry inherent risks, including fumbles exacerbated by wet conditions that reduce grip on the slick ball, leading to higher turnover rates during inclement weather.[76] High-speed collisions during returns also elevate injury risks, with returned punts associated with an 8.31 times higher odds of concussions compared to fair catches.[77] Despite these dangers, the average NFL punt return nets about 9.9 yards, providing critical field position gains when executed successfully.[78] By 2025, trends show increased use of directional returns, where returners angle laterally to exploit sidelines against precise punter placement aimed at pinning teams deep, reducing straight-line returns and favoring fair catches inside the 20-yard line due to enhanced punter accuracy.[79] This adaptation counters the punting team's coverage strategies by minimizing exposure to central gunners while maximizing short gains along the boundaries.[73]Records

Punting Records

Punting records in gridiron football encompass notable achievements in distance, average yardage, volume, and precision, spanning both the NFL and CFL. These metrics highlight the evolution of the position, influenced by rule changes, equipment advancements, and specialized training. In the NFL, the longest punt stands at 98 yards, kicked by Steve O'Neal of the New York Jets against the Denver Broncos on September 21, 1969.[80] In the CFL, the record is 108 yards, first achieved by Zenon Andrusyshyn of the Toronto Argonauts against the Edmonton Eskimos on October 23, 1977, and later tied by Chris Milo of the Saskatchewan Roughriders against the Hamilton Tiger-Cats on October 29, 2011.[81] Single-season punting averages have seen dramatic increases, reflecting improved techniques and athleticism. Ryan Stonehouse set the NFL record with a 53.1-yard average in 2022 while with the Tennessee Titans, surpassing a mark that had stood for over eight decades.[82] In the 2025 season, Ryan Rehkow of the Cincinnati Bengals has led with a 52.8-yard average through 38 punts (as of November 2025).[83] Career records emphasize longevity and consistency. In the NFL, Jeff Feagles holds the mark for most punts with 1,713 over 22 seasons from 1988 to 2007.[84] In the CFL, Bob Cameron amassed the most career punting yards at 134,301 during his tenure with the Winnipeg Blue Bombers from 1974 to 2007.[85] Accuracy is measured by punts landing inside the 20-yard line and touchback rates, which indicate control and field position value. Johnny Hekker, a three-time Pro Bowl selection, achieved 33.8% of his career punts (340 out of 1,005) inside the 20-yard line through the 2025 season.[86] Elite punters like Shane Lechler maintained low touchback rates, with only 286 touchbacks in 1,444 punts (about 20%) over his 18-year NFL career, prioritizing directional kicking over raw distance.[87] Key milestones include the first NFL season averaging 50 yards per punt, achieved by Washington Redskins quarterback Sammy Baugh in 1940 with 51.4 yards, a benchmark that underscored early innovations in punting form.[88] Since the 1990s, Australian punters—trained in rugby league's drop punt—have transformed NFL records, with pioneers like Darren Bennett and Sav Rocca introducing superior hang time and accuracy, leading to higher averages and more inside-20 placements league-wide.[89]| Category | Record Holder | Value | League/Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longest Punt (NFL) | Steve O'Neal | 98 yards | 1969 |

| Longest Punt (CFL) | Zenon Andrusyshyn / Chris Milo | 108 yards | 1977 / 2011 |

| Single-Season Avg. (NFL) | Ryan Stonehouse | 53.1 yards | 2022 |

| Career Punts (NFL) | Jeff Feagles | 1,713 | 1988–2007 |

| Career Yards (CFL) | Bob Cameron | 134,301 yards | 1974–2007 |

Return Records

In professional gridiron football, punt return touchdowns represent a pinnacle of explosive playmaking, with Devin Hester holding the NFL career record at 14 such scores across his tenure with multiple teams from 2006 to 2016.[90] In the CFL, Henry "Gizmo" Williams established the all-time mark with 26 punt return touchdowns over his 14-season career primarily with the Edmonton Eskimos, a figure that underscores the league's emphasis on return opportunities due to its wider field dimensions.[91] The longest punt return in NFL history is 103 yards for a touchdown by Robert Bailey of the Los Angeles Rams against the New Orleans Saints on October 23, 1994, a play that highlighted the potential for game-altering speed in special teams matchups.[92] In the CFL, the record is 113 yards for a touchdown by Sam Rogers of the Hamilton Tiger-Cats in 1995, capitalizing on the league's larger playing surface to create extended running lanes. Single-season achievements further illustrate returner dominance, as Hester tied the NFL record with four punt return touchdowns in 2007 while with the Chicago Bears, contributing to his broader legacy of six combined return touchdowns that year. As of the 2025 CFL season, Seven McGee of the BC Lions led in punt return volume with 53 returns for 516 yards and one touchdown, including a 93-yard score, though his average of 9.7 yards per return reflected the tactical caution often employed in modern returns.[93] Career yardage leaders emphasize endurance and consistency, with Brian Mitchell amassing an NFL-record 4,999 punt return yards from 1990 to 2003 across stints with the Washington Redskins and Philadelphia Eagles, far surpassing contemporaries in total volume.[94] Williams, meanwhile, leads the CFL with 11,257 punt return yards, a total bolstered by the league's design that encourages more frequent and longer returns compared to the NFL's narrower field.[91] Post-2023, punt return statistics in both leagues have shown relative stability amid rule tweaks primarily affecting kickoffs, with no major alterations to fair catch incentives that might further reduce return attempts. In NCAA football, notable 100-yard punt returns for touchdowns include examples like Brandon Stephens' 100-yarder for the University of Maryland against Indiana in 2017, exemplifying the high-risk, high-reward nature of college special teams play.| Category | NFL Leader | Statistic | CFL Leader | Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career Punt Return TDs | Devin Hester | 14 | Gizmo Williams | 26 |

| Longest Punt Return | Robert Bailey (1994) | 103 yards | Sam Rogers (1995) | 113 yards |

| Single-Season Punt Return TDs | Devin Hester (2007) | 4 (tied) | Gizmo Williams (multiple seasons) | 5 |

| Career Punt Return Yards | Brian Mitchell | 4,999 | Gizmo Williams | 11,257 |