Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Weather

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

Weather refers to the state of the Earth's atmosphere at a specific place and time, typically described in terms of temperature, humidity, cloud cover, and stability.[1] On Earth, most weather phenomena occur in the lowest layer of the planet's atmosphere, the troposphere,[2][3] just below the stratosphere. Weather refers to day-to-day temperature, precipitation, and other atmospheric conditions, whereas climate is the term for the averaging of atmospheric conditions over longer periods of time.[4] When used without qualification, "weather" is generally understood to mean the weather of Earth.

Weather is driven by air pressure, temperature, and moisture differences between one place and another. These differences can occur due to the Sun's angle at any particular spot, which varies with latitude. The strong temperature contrast between polar and tropical air gives rise to the largest scale atmospheric circulations: the Hadley cell, the Ferrel cell, the polar cell, and the jet stream. Weather systems in the middle latitudes, such as extratropical cyclones, are caused by instabilities of the jet streamflow. Because Earth's axis is tilted relative to its orbital plane (called the ecliptic), sunlight is incident at different angles at different times of the year. On Earth's surface, temperatures usually range ±40 °C (−40 °F to 104 °F) annually. Over thousands of years, changes in Earth's orbit can affect the amount and distribution of solar energy received by Earth, thus influencing long-term climate and global climate change.

Surface temperature differences in turn cause pressure differences. Higher altitudes are cooler than lower altitudes, as most atmospheric heating is due to contact with the Earth's surface while radiative losses to space are mostly constant. Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology to predict the state of the atmosphere for a future time and a given location. Earth's weather system is a chaotic system; as a result, small changes to one part of the system can grow to have large effects on the system as a whole. Human attempts to control the weather have occurred throughout history, and there is evidence that human activities such as agriculture and industry have modified weather patterns.

Studying how the weather works on other planets has been helpful in understanding how weather works on Earth. A famous landmark in the Solar System, Jupiter's Great Red Spot, is an anticyclonic storm known to have existed for at least 300 years. However, the weather is not limited to planetary bodies. A star's corona is constantly being lost to space, creating what is essentially a very thin atmosphere throughout the Solar System. The movement of mass ejected from the Sun is known as the solar wind.

Causes

[edit]

On Earth, common weather phenomena include wind, cloud, rain, snow, fog and dust storms. Some more common events include natural disasters such as tornadoes, hurricanes, typhoons and ice storms. Almost all familiar weather phenomena occur in the troposphere (the lower part of the atmosphere).[3] Weather does occur in the stratosphere and can affect weather lower down in the troposphere, but the exact mechanisms are poorly understood.[5]

Weather occurs primarily due to air pressure, temperature and moisture differences from one place to another. These differences can occur due to the sun angle at any particular spot, which varies by latitude in the tropics. In other words, the farther from the tropics one lies, the lower the sun angle is, which causes those locations to be cooler due to the spread of the sunlight over a greater surface.[6] The strong temperature contrast between polar and tropical air gives rise to the large scale atmospheric circulation cells and the jet stream.[7] Weather systems in the mid-latitudes, such as extratropical cyclones, are caused by instabilities of the jet stream flow (see baroclinity).[8] Weather systems in the tropics, such as monsoons or organized thunderstorm systems, are caused by different processes.

Because the Earth's axis is tilted relative to its orbital plane, sunlight is incident at different angles at different times of the year. In June the Northern Hemisphere is tilted towards the Sun, so at any given Northern Hemisphere latitude sunlight falls more directly on that spot than in December (see Effect of sun angle on climate).[10] This effect causes seasons. Over thousands to hundreds of thousands of years, changes in Earth's orbital parameters affect the amount and distribution of solar energy received by the Earth and influence long-term climate. (See Milankovitch cycles).[11]

The uneven solar heating (the formation of zones of temperature and moisture gradients, or frontogenesis) can also be due to the weather itself in the form of cloudiness and precipitation.[12] Higher altitudes are typically cooler than lower altitudes, which is the result of higher surface temperature and radiational heating, which produces the adiabatic lapse rate.[13][14] In some situations, the temperature actually increases with height. This phenomenon is known as an inversion and can cause mountaintops to be warmer than the valleys below. Inversions can lead to the formation of fog and often act as a cap that suppresses thunderstorm development. On local scales, temperature differences can occur because different surfaces (such as oceans, forests, ice sheets, or human-made objects) have differing physical characteristics such as reflectivity, roughness, or moisture content.

Surface temperature differences in turn cause pressure differences. A hot surface warms the air above it causing it to expand and lower the density and the resulting surface air pressure.[15] The resulting horizontal pressure gradient moves the air from higher to lower pressure regions, creating a wind, and the Earth's rotation then causes deflection of this airflow due to the Coriolis effect.[16] The simple systems thus formed can then display emergent behaviour to produce more complex systems and thus other weather phenomena. Large scale examples include the Hadley cell while a smaller scale example would be coastal breezes.

The atmosphere is a chaotic system. As a result, small changes to one part of the system can accumulate and magnify to cause large effects on the system as a whole.[17] This atmospheric instability makes weather forecasting less predictable than tidal waves or eclipses.[18] Although it is difficult to accurately predict weather more than a few days in advance, weather forecasters are continually working to extend this limit through meteorological research and refining current methodologies in weather prediction. However, it is theoretically impossible to make useful day-to-day predictions more than about two weeks ahead, imposing an upper limit to potential for improved prediction skill.[19]

Shaping the planet Earth

[edit]Weather is one of the fundamental processes that shape the Earth. The process of weathering breaks down the rocks and soils into smaller fragments and then into their constituent substances.[20] During rains precipitation, the water droplets absorb and dissolve carbon dioxide from the surrounding air. This causes the rainwater to be slightly acidic, which aids the erosive properties of water. The released sediment and chemicals are then free to take part in chemical reactions that can affect the surface further (such as acid rain), and sodium and chloride ions (salt) deposited in the seas/oceans. The sediment may reform in time and by geological forces into other rocks and soils. In this way, weather plays a major role in erosion of the surface.[21]

Effect on humans

[edit]Weather, seen from an anthropological perspective, is something all humans in the world constantly experience through their senses, at least while being outside. There are socially and scientifically constructed understandings of what weather is, what makes it change, the effect the weather, and especially inclement weather, has on humans in different situations, etc.[22] Therefore, weather is something people often communicate about.

In the United States, the National Weather Service has an annual report for fatalities, injury, and total damage costs which include crop and property. They gather this data via National Weather Service offices located throughout the 50 states in the United States as well as Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands. As of 2019, tornadoes have had the greatest impact on humans with 42 fatalities while costing crop and property damage over 3 billion dollars.[23]

Effects on populations

[edit]

The weather has played a large and sometimes direct part in human history. Aside from climatic changes that have caused the gradual drift of populations (for example the desertification of the Middle East, and the formation of land bridges during glacial periods), extreme weather events have caused smaller scale population movements and intruded directly in historical events. One such event is the saving of Japan from invasion by the Mongol fleet of Kublai Khan by the Kamikaze winds in 1281.[24] French claims to Florida came to an end in 1565 when a hurricane destroyed the French fleet, allowing Spain to conquer Fort Caroline.[25] More recently, Hurricane Katrina redistributed over one million people from the central Gulf coast elsewhere across the United States, becoming the largest diaspora in the history of the United States.[26]

The Little Ice Age caused crop failures and famines in Europe. During the period known as the Grindelwald Fluctuation (1560–1630), volcanic forcing events[27] seem to have led to more extreme weather events.[28] These included droughts, storms and unseasonal blizzards, as well as causing the Swiss Grindelwald Glacier to expand. The 1690s saw the worst famine in France since the Middle Ages. Finland suffered a severe famine in 1696–1697, during which about one-third of the Finnish population died.[29]

Forecasting

[edit]

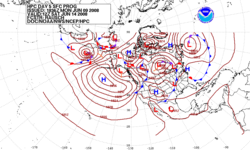

Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology to predict the state of the atmosphere for a future time and a given location. Human beings have attempted to predict the weather informally for millennia, and formally since at least the nineteenth century.[30] Weather forecasts are made by collecting quantitative data about the current state of the atmosphere and using scientific understanding of atmospheric processes to project how the atmosphere will evolve.[31]

Once an all-human endeavor based mainly upon changes in barometric pressure, current weather conditions, and sky condition,[32][33] forecast models are now used to determine future conditions. On the other hand, human input is still required to pick the best possible forecast model to base the forecast upon, which involves many disciplines such as pattern recognition skills, teleconnections, knowledge of model performance, and knowledge of model biases.

The chaotic nature of the atmosphere, the massive computational power required to solve the equations that describe the atmosphere, the error involved in measuring the initial conditions, and an incomplete understanding of atmospheric processes mean that forecasts become less accurate as of the difference in current time and the time for which the forecast is being made (the range of the forecast) increases. The use of ensembles and model consensus helps to narrow the error and pick the most likely outcome.[34][35][36]

There are a variety of end users to weather forecasts. Weather warnings are important forecasts because they are used to protect life and property.[37][38] Forecasts based on temperature and precipitation are important to agriculture,[39][40][41][42] and therefore to commodity traders within stock markets. Temperature forecasts are used by utility companies to estimate demand over coming days.[43][44][45]

In some areas, people use weather forecasts to determine what to wear on a given day. Since outdoor activities are severely curtailed by heavy rain, snow and the wind chill, forecasts can be used to plan activities around these events and to plan ahead to survive through them.

Tropical weather forecasting is different from that at higher latitudes. The sun shines more directly on the tropics than on higher latitudes (at least on average over a year), which makes the tropics warm (Stevens 2011). And, the vertical direction (up, as one stands on the Earth's surface) is perpendicular to the Earth's axis of rotation at the equator, while the axis of rotation and the vertical are the same at the pole; this causes the Earth's rotation to influence the atmospheric circulation more strongly at high latitudes than low latitudes. Because of these two factors, clouds and rainstorms in the tropics can occur more spontaneously compared to those at higher latitudes, where they are more tightly controlled by larger-scale forces in the atmosphere. Because of these differences, clouds and rain are more difficult to forecast in the tropics than at higher latitudes. On the other hand, the temperature is easily forecast in the tropics, because it does not change much.[46]

Modification

[edit]The aspiration to control the weather is evident throughout human history: from ancient rituals intended to bring rain for crops to the U.S. Military Operation Popeye, an attempt to disrupt supply lines by lengthening the North Vietnamese monsoon. The most successful attempts at influencing weather involve cloud seeding; they include the fog- and low stratus dispersion techniques employed by major airports, techniques used to increase winter precipitation over mountains, and techniques to suppress hail.[47] A recent example of weather control was China's preparation for the 2008 Summer Olympic Games. China shot 1,104 rain dispersal rockets from 21 sites in the city of Beijing in an effort to keep rain away from the opening ceremony of the games on 8 August 2008. Guo Hu, head of the Beijing Municipal Meteorological Bureau (BMB), confirmed the success of the operation with 100 millimeters falling in Baoding City of Hebei Province, to the southwest and Beijing's Fangshan District recording a rainfall of 25 millimeters.[48]

Whereas there is inconclusive evidence for these techniques' efficacy, there is extensive evidence that human activity such as agriculture and industry results in inadvertent weather modification:[47]

- Acid rain, caused by industrial emission of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere, adversely affects freshwater lakes, vegetation, and structures.

- Anthropogenic pollutants reduce air quality and visibility.

- Climate change caused by human activities that emit greenhouse gases into the air is expected to affect the frequency of extreme weather events such as drought, extreme temperatures, flooding, high winds, and severe storms.[49]

- Heat, generated by large metropolitan areas have been shown to minutely affect nearby weather, even at distances as far as 1,600 kilometres (990 mi).[50]

The effects of inadvertent weather modification may pose serious threats to many aspects of civilization, including ecosystems, natural resources, food and fiber production, economic development, and human health.[51]

Microscale meteorology

[edit]Microscale meteorology is the study of short-lived atmospheric phenomena smaller than mesoscale, about 1 km or less. These two branches of meteorology are sometimes grouped together as "mesoscale and microscale meteorology" (MMM) and together study all phenomena smaller than synoptic scale; that is they study features generally too small to be depicted on a weather map. These include small and generally fleeting cloud "puffs" and other small cloud features.[52]

Extremes on Earth

[edit]

On Earth, temperatures usually range ±40 °C (100 °F to −40 °F) annually. The range of climates and latitudes across the planet can offer extremes of temperature outside this range. The coldest air temperature ever recorded on Earth is −89.2 °C (−128.6 °F), at Vostok Station, Antarctica on 21 July 1983. The hottest air temperature ever recorded was 57.7 °C (135.9 °F) at ʽAziziya, Libya, on 13 September 1922,[54] but that reading was deemed illegitimate by the World Meteorological Organization. The highest recorded average annual temperature was 34.4 °C (93.9 °F) at Dallol, Ethiopia.[55] The coldest recorded average annual temperature was −55.1 °C (−67.2 °F) at Vostok Station, Antarctica.[56]

The coldest average annual temperature in a permanently inhabited location is at Eureka, Nunavut, in Canada, where the annual average temperature is −19.7 °C (−3.5 °F).[57]

The windiest place ever recorded is in Antarctica, Commonwealth Bay (George V Coast). Here the gales reach 199 mph (320 km/h).[58] Furthermore, the greatest snowfall in a period of twelve months occurred in Mount Rainier, Washington, US. It was recorded as 31,102 mm (102.04 ft) of snow.[59]

Extraterrestrial weather

[edit]

Studying how the weather works on other planets has been seen as helpful in understanding how it works on Earth.[60] Weather on other planets follows many of the same physical principles as weather on Earth, but occurs on different scales and in atmospheres having different chemical composition. The Cassini–Huygens mission to Titan discovered clouds formed from methane or ethane which deposit rain composed of liquid methane and other organic compounds.[61] Earth's atmosphere includes six latitudinal circulation zones, three in each hemisphere.[62] In contrast, Jupiter's banded appearance shows many such zones,[63] Titan has a single jet stream near the 50th parallel north latitude,[64] and Venus has a single jet near the equator.[65]

One of the most famous landmarks in the Solar System, Jupiter's Great Red Spot, is an anticyclonic storm known to have existed for at least 300 years.[66] On other giant planets, the lack of a surface allows the wind to reach enormous speeds: gusts of up to 600 metres per second (about 2,100 km/h or 1,300 mph) have been measured on the planet Neptune.[67] This has created a puzzle for planetary scientists. The weather is ultimately created by solar energy and the amount of energy received by Neptune is only about 1⁄900 of that received by Earth, yet the intensity of weather phenomena on Neptune is far greater than on Earth.[68] As of 2007[update], the strongest planetary winds discovered are on the extrasolar planet HD 189733 b, which is thought to have easterly winds moving at more than 9,600 kilometres per hour (6,000 mph).[69]

Space weather

[edit]

Weather is not limited to planetary bodies. Like all stars, the Sun's corona is constantly being lost to space, creating what is essentially a very thin atmosphere throughout the Solar System. The movement of mass ejected from the Sun is known as the solar wind. Inconsistencies in this wind and larger events on the surface of the star, such as coronal mass ejections, form a system that has features analogous to conventional weather systems (such as pressure and wind) and is generally known as space weather. Coronal mass ejections have been tracked as far out in the Solar System as Saturn.[70] The activity of this system can affect planetary atmospheres and occasionally surfaces. The interaction of the solar wind with the terrestrial atmosphere can produce spectacular aurorae,[71] and can play havoc with electrically sensitive systems such as electricity grids and radio signals.[72]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Weather." Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived 9 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 27 June 2008.

- ^ "Hydrosphere". Glossary of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- ^ a b "Troposphere". Glossary of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Climate". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- ^ O'Carroll, Cynthia M. (18 October 2001). "Weather Forecasters May Look Sky-high For Answers". Goddard Space Flight Center (NASA). Archived from the original on 12 July 2009.

- ^ NASA. World Book at NASA: Weather. Archived copy at WebCite (10 March 2013). Retrieved on 27 June 2008.

- ^ John P. Stimac. [1] Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Air pressure and wind. Retrieved on 8 May 2008.

- ^ Carlyle H. Wash, Stacey H. Heikkinen, Chi-Sann Liou, and Wendell A. Nuss. A Rapid Cyclogenesis Event during GALE IOP 9. Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Cabbage, Michael; McCarthy, Leslie; Norton, Karen (20 January 2016). "NASA, NOAA Analyses Reveal Record-Shattering Global Warm Temperatures in 2015". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Windows to the Universe. Earth's Tilt Is the Reason for the Seasons! Archived 8 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Milankovitch, Milutin. Canon of Insolation and the Ice Age Problem. Zavod za Udz̆benike i Nastavna Sredstva: Belgrade, 1941. ISBN 86-17-06619-9.

- ^ Ron W. Przybylinski. The Concept of Frontogenesis and its Application to Winter Weather Forecasting. Archived 24 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Mark Zachary Jacobson (2005). Fundamentals of Atmospheric Modeling (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83970-9. OCLC 243560910.

- ^ C. Donald Ahrens (2006). Meteorology Today (8th ed.). Brooks/Cole Publishing. ISBN 978-0-495-01162-0. OCLC 224863929.

- ^ Michel Moncuquet. Relation between density and temperature. Archived 27 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Earth. Wind. Archived 9 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Spencer Weart. The Discovery of Global Warming. Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Lorenz, Edward (July 1969). "How Much Better Can Weather Prediction Become?" (PDF). web.mit.edu/. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "The Discovery of Global Warming: Chaos in the Atmosphere". history.aip.org. January 2017. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ NASA. NASA Mission Finds New Clues to Guide Search for Life on Mars. Archived 11 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ West Gulf River Forecast Center. Glossary of Hydrologic Terms: E Archived 16 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Crate, Susan A; Nuttall, Mark, eds. (2009). Anthropology and Climate Change: From Encounters to Actions (PDF). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. pp. 70–86, i.e. the chapter 'Climate and weather discourse in anthropology: from determinism to uncertain futures' by Nicholas Peterson & Kenneth Broad. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ United States. National Weather Service. Office of Climate, Water, Weather Services, & National Climatic Data Center. (2000). Weather Related Fatality and Injury Statistics.

- ^ James P. Delgado. Relics of the Kamikaze. Archived 6 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Mike Strong. Fort Caroline National Memorial. Archived 17 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Anthony E. Ladd, John Marszalek, and Duane A. Gill. The Other Diaspora: New Orleans Student Evacuation Impacts and Responses Surrounding Hurricane Katrina. Archived 24 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 29 March 2008.

- ^ Jason Wolfe, Volcanoes and Climate Change Archived 29 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, NASA, 28 July 2020). Date retrieved: 28 May 2021.

- ^ Jones, Evan T.; Hewlett, Rose; Mackay, Anson W. (5 May 2021). "Weird weather in Bristol during the Grindelwald Fluctuation (1560–1630)". Weather. 76 (4): 104–110. Bibcode:2021Wthr...76..104J. doi:10.1002/wea.3846. hdl:1983/28c52f89-91be-4ae4-80e9-918cd339da95. S2CID 225239334.

- ^ "Famine in Scotland: The 'Ill Years' of the 1690s". Karen J. Cullen (2010). Edinburgh University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-7486-3887-3

- ^ Eric D. Craft. An Economic History of Weather Forecasting. Archived 3 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 15 April 2007.

- ^ NASA. Weather Forecasting Through the Ages. Archived 10 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- ^ Weather Doctor. Applying The Barometer To Weather Watching. Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- ^ Mark Moore. Field Forecasting: A Short Summary. Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- ^ Klaus Weickmann, Jeff Whitaker, Andres Roubicek and Catherine Smith. The Use of Ensemble Forecasts to Produce Improved Medium Range (3–15 days) Weather Forecasts. Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 16 February 2007.

- ^ Todd Kimberlain. Tropical cyclone motion and intensity talk (June 2007). Archived 27 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 21 July 2007.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch, Mike Fiorino, and Chris Landsea. TPC/NHC’S Review of the NCEP Production Suite For 2006.[permanent dead link] Retrieved on 5 May 2008.

- ^ National Weather Service. National Weather Service Mission Statement. Archived 24 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- ^ "National Meteorological Service of Slovenia". Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ Blair Fannin. Dry weather conditions continue for Texas. Archived 3 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 May 2008.

- ^ Dr. Terry Mader. Drought Corn Silage. Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 May 2008.

- ^ Kathryn C. Taylor. Peach Orchard Establishment and Young Tree Care. Archived 24 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 May 2008.

- ^ Associated Press. After Freeze, Counting Losses to Orange Crop. Archived 31 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 May 2008.

- ^ The New York Times. Futures/Options; Cold Weather Brings Surge In Prices of Heating Fuels. Archived 14 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- ^ BBC. Heatwave causes electricity surge. Archived 20 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- ^ Toronto Catholic Schools. The Seven Key Messages of the Energy Drill Program. Archived 17 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- ^ "Tropical Weather | Learn Science at Scitable". nature.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Planned and Inadvertent Weather Modification". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010.

- ^ Huanet, Xin (9 August 2008). "Beijing disperses rain to dry Olympic night". Chinaview. Archived from the original on 12 August 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ "The Regional Impacts of Climate Change". grida.no. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ Zhang, Guang (28 January 2012). "Cities Affect Temperatures for Thousands of Miles". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ "The Regional Impacts of Climate Change". grida.no. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ Rogers, R. (1989). A Short Course in Cloud Physics. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-7506-3215-7.

- ^ "Mean Monthly Temperature Records Across the Globe / Timeseries of Global Land and Ocean Areas at Record Levels for July from 1951-2023". NCEI.NOAA.gov. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). August 2023. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. (change "202307" in URL to see years other than 2023, and months other than 07=July)

- ^ Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation. Archived 25 May 2012 at archive.today National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved on 21 June 2007.

- ^ Glenn Elert. Hottest Temperature on Earth. Archived 14 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Glenn Elert. Coldest Temperature On Earth. Archived 10 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000 – Eureka". Archived from the original on 11 November 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ "The Places with the Most Extreme Climates". Inkerman™. 10 September 2020. Archived from the original on 5 April 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ "Greatest snowfall in 12 months". Guinness World Records. 18 February 1972. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Britt, Robert Roy (6 March 2001). "The Worst Weather in the Solar System". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2001.

- ^ M. Fulchignoni; F. Ferri; F. Angrilli; A. Bar-Nun; M.A. Barucci; G. Bianchini; et al. (2002). "The Characterisation of Titan's Atmospheric Physical Properties by the Huygens Atmospheric Structure Instrument (Hasi)". Space Science Reviews. 104 (1): 395–431. Bibcode:2002SSRv..104..395F. doi:10.1023/A:1023688607077. S2CID 189778612.

- ^ Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Overview – Climate: The Spherical Shape of the Earth: Climatic Zones. Archived 26 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Anne Minard. Jupiter's "Jet Stream" Heated by Surface, Not Sun. Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ ESA: Cassini–Huygens. The jet stream of Titan. Archived 25 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Georgia State University. The Environment of Venus. Archived 7 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Ellen Cohen. "Jupiter's Great Red Spot". Hayden Planetarium. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ^ Suomi, V.E.; Limaye, S.S.; Johnson, D.R. (1991). "High Winds of Neptune: A possible mechanism". Science. 251 (4996): 929–932. Bibcode:1991Sci...251..929S. doi:10.1126/science.251.4996.929. PMID 17847386. S2CID 46419483.

- ^ Sromovsky, Lawrence A. (14 October 1998). "Hubble Provides a Moving Look at Neptune's Stormy Disposition". HubbleSite. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2006.

- ^ Knutson, Heather A.; David Charbonneau; Lori E. Allen; Jonathan J. Fortney; Eric Agol; Nicolas B. Cowan; et al. (10 May 2007). "A map of the day–night contrast of the extrasolar planet HD 189733b". Nature. 447 (7141): 183–186. arXiv:0705.0993. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..183K. doi:10.1038/nature05782. PMID 17495920. S2CID 4402268.

- ^ Bill Christensen. Shock to the (Solar) System: Coronal Mass Ejection Tracked to Saturn. Archived 1 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ AlaskaReport. What Causes the Aurora Borealis? Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 June 2008.

- ^ Viereck, Rodney (Summer 2007). "Space Weather: What is it? How Will it Affect You?". Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at University of Colorado Boulder. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

powerpoint download

External links

[edit]Weather

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Weather refers to the state of the atmosphere at a specific time and location, characterized by variables such as temperature, atmospheric pressure, humidity, wind speed and direction, and precipitation.[3] These elements describe conditions that directly affect human activities, property, and the environment over short periods, typically ranging from minutes to weeks.[9] Unlike long-term statistical summaries, weather captures instantaneous and rapidly evolving physical states driven by atmospheric dynamics.[10] The spatial and temporal scales of weather phenomena span from microscale processes, involving local turbulence and eddies under 2 kilometers in extent lasting seconds to minutes, to mesoscale features like thunderstorms spanning 2 to 1,000 kilometers over hours to a day, and synoptic-scale systems such as cyclones covering 1,000 to 5,000 kilometers persisting for days to weeks.[11] For instance, daily temperature fluctuations in a urban area exemplify microscale variability influenced by surface heating, while a passing cold front represents synoptic-scale motion affecting continental regions.[12] This hierarchy reflects the hierarchical organization of atmospheric motions, where smaller-scale phenomena are embedded within larger ones, contributing to the overall variability observed.[13] Weather must be distinguished from climate, which aggregates atmospheric conditions over decades—conventionally 30 years or more—to derive average patterns of temperature, precipitation, and other metrics.[14] Conflating short-term weather extremes with climate trends risks misattributing natural chaotic fluctuations, such as intra-seasonal variability or regional anomalies, to shifts in underlying long-term averages, thereby overlooking the atmosphere's inherent unpredictability at sub-decadal scales.[2] Empirical records, including surface observations since the 19th century, demonstrate that weather's high variability includes events like heatwaves or cold snaps that deviate from multi-year norms without implying permanent climatic alteration.[15] This demarcation underscores the primacy of direct measurement of atmospheric states over aggregated inferences for understanding immediate environmental conditions.[16]Physical Properties of the Atmosphere

Earth's atmosphere is composed primarily of dry air, consisting of 78.08% nitrogen, 20.95% oxygen, and 0.93% argon by volume, alongside trace gases such as carbon dioxide at about 0.0407%.[17] [18] Water vapor, absent from dry air measurements, varies spatially and temporally from near 0% in polar or arid regions to approaching 4% by volume in warm, humid tropical environments, enabling key weather processes through phase changes and latent heat transfer.[19] The troposphere forms the lowest layer of the atmosphere, extending from the surface to an average height of 12 km at mid-latitudes (varying from 8 km at poles to 18 km in tropics), and contains roughly 80% of the total atmospheric mass along with 99% of the water vapor.[20] [21] Within this layer, temperature declines with altitude at the standard environmental lapse rate of 6.5 °C per kilometer, driven by the adiabatic cooling of ascending air under hydrostatic equilibrium.[22] Barometric pressure at sea level averages 1013.25 hPa and diminishes exponentially with elevation per the barometric formula, , where is the scale height (approximately 8.4 km under isothermal conditions at 288 K), reflecting the decreasing density of air molecules under gravity.[23] The Coriolis effect, a consequence of Earth's 7.292 × 10^{-5} rad/s rotation, imposes an apparent deflection on horizontally moving air masses—rightward in the Northern Hemisphere and leftward in the Southern—arising from the conservation of angular momentum in a rotating frame.[24]Causal Mechanisms

Energy Balance and Thermodynamics

The Earth's energy balance is governed by the influx of solar radiation and the outflow of terrestrial infrared radiation, achieving approximate equilibrium at an average of 240 W/m² absorbed globally. Incoming shortwave radiation at the top of the atmosphere measures approximately 1361 W/m², known as the solar constant, but due to the planet's spherical geometry and diurnal cycle, the global average incident flux is about 340 W/m². Of this, roughly 30% is reflected back to space by the atmosphere, clouds, and surface, corresponding to Earth's Bond albedo of 0.30, leaving 240 W/m² for absorption by the surface and atmosphere. This net absorption establishes the primary energy input driving atmospheric temperatures and gradients, with imbalances on short timescales leading to weather variability through thermodynamic adjustments.[25][26][27] Thermodynamic principles underpin these processes via the first and second laws. The first law of thermodynamics, conservation of energy, manifests in adiabatic expansion: as air parcels rise due to buoyancy from surface heating, they encounter decreasing pressure, expand, and perform work on surroundings without heat exchange, reducing internal energy and causing cooling at the dry adiabatic lapse rate of approximately 9.8°C per kilometer. This cooling enables supersaturation and condensation when parcels reach the dew point, releasing latent heat that partially offsets further temperature drop. The second law dictates irreversible heat flow from warmer equatorial regions to cooler poles, but direct conduction is inefficient; instead, convection acts as a heat engine, converting thermal gradients into mechanical work to transport energy latitudinally.[28] Radiative-convective equilibrium modulates surface temperatures beyond blackbody expectations. Absent an atmosphere, the effective radiating temperature would be about 255 K (-18°C) based on Stefan-Boltzmann emission balancing 240 W/m² absorption; the actual average surface temperature of 288 K (15°C) results from the natural greenhouse effect, wherein atmospheric gases absorb and re-emit infrared radiation. Water vapor dominates this trapping, accounting for the majority of the effect due to its abundance and spectral overlap with Earth's emission peaks, while carbon dioxide contributes via absorption bands around 15 μm, with pre-industrial concentrations at 280 ppm exerting a baseline forcing. These gases maintain a vertical temperature profile where the troposphere warms the surface through downward longwave radiation, sustaining convective instability essential for weather dynamics. Hadley cells exemplify this as thermally direct circulations functioning akin to Carnot engines, with efficiency proportional to the ratio of equatorial surface to tropopause temperatures, empirically around 2-5% based on observed dissipation.[29][30]Dynamics of Atmospheric Motion

Horizontal air motion in the atmosphere results from the pressure gradient force (PGF), which accelerates parcels toward lower pressure regions perpendicular to isobars, with magnitude given by , where is air density and the horizontal pressure gradient. On a non-rotating Earth, this would produce direct radial inflow to low-pressure centers, but Earth's rotation introduces the Coriolis force, a fictitious deflection acting perpendicular to velocity: to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and left in the Southern Hemisphere, with magnitude , where ( is Earth's angular velocity, latitude) and is wind speed.[31] In the free atmosphere above the frictional boundary layer, typically above 1 km altitude, winds attain geostrophic balance: the PGF is exactly opposed by the Coriolis force, yielding straight-line flow parallel to isobars at speeds , increasing with pressure gradient strength and decreasing poleward due to smaller .[32] This balance explains mid-latitude upper-level winds as zonal or meridional without radial components, observable in constant pressure charts where streamlines align with height contours.[32] Surface friction, acting within the planetary boundary layer (roughly 1 km thick), opposes motion through turbulent drag from terrain and vegetation, reducing wind speeds by 20-50% compared to geostrophic values and thereby weakening the Coriolis force.[33] [34] This imbalance allows the PGF to drive air across isobars toward low centers (convergence) or away from highs (divergence), initiating vertical mixing and Ekman spirals where wind veers clockwise with height in the Northern Hemisphere.[33] [34] Large-scale patterns emerge from these dynamics: subtropical high-pressure systems produce trade winds via PGF directed equatorward, deflected by Coriolis to northeast-to-southwest in the Northern Hemisphere (average speeds 5-10 m/s) and southeast-to-northwest in the Southern.[35] Polar highs yield easterlies, with PGF poleward deflected to east-to-west flow (speeds often under 5 m/s due to weak gradients).[36] Rossby waves, planetary-scale undulations (wavelengths 2000-6000 km), arise from the meridional variation of the Coriolis parameter (), restoring displaced air parcels via conservation of potential vorticity and propagating westward relative to mean flow, modulating mid-latitude westerlies.[37] [38]Hydrological Cycle

The hydrological cycle describes the continuous circulation of water through Earth's atmosphere, involving phase changes between liquid, vapor, and solid states that drive both moisture transport and energy redistribution. Water primarily enters the atmosphere via evaporation from oceans and evapotranspiration from land surfaces, with global averages estimated at approximately 505 mm per year in depth-equivalent terms across the planet's surface. This process absorbs substantial latent heat—about 2.5 MJ per kg of water vaporized at typical surface temperatures—facilitating the upward transport of energy far more efficiently than sensible heat conduction or radiation, as vapor rises with air parcels before condensation releases the stored energy aloft.[39] Condensation occurs when water vapor cools to its dew point, forming cloud droplets on microscopic particles known as cloud condensation nuclei, which include natural dust, sea salt, and sulfate aerosols that lower the energy barrier for droplet nucleation.[40] Without sufficient nuclei, supersaturation can exceed 100% relative humidity, but their presence enables efficient phase transition, releasing latent heat that warms surrounding air and sustains vertical motion. Precipitation ensues when droplets coalesce or freeze, returning water to the surface via rain, snow, or hail, completing the cycle and balancing global inputs and outputs within observational margins of error.[41] In regions of atmospheric subsidence, such as subtropical high-pressure zones, descending air undergoes adiabatic compression, warming at the dry adiabatic lapse rate of approximately 9.8°C per km and thereby reducing relative humidity through thermal expansion, which evaporates cloud droplets and inhibits further condensation.[42] This drying mechanism reinforces aridity in descending branches of the Hadley circulation. Stable isotopes, particularly δ¹⁸O ratios in precipitation, serve as tracers for moisture provenance; rainwater depleted in heavier ¹⁸O (more negative δ¹⁸O values) often originates from high-latitude or high-altitude evaporation sources where fractionation enriches vapor in lighter isotopes during uplift and cooling.[43] Such isotopic signatures, measured via spectroscopy, confirm dominant oceanic moisture recycling without implying long-term trends.[44]Weather Phenomena

Clouds and Precipitation

Clouds form primarily through the adiabatic cooling of rising moist air parcels, which expand and cool as they ascend due to decreasing atmospheric pressure, eventually reaching the dew point temperature where water vapor condenses onto aerosol nuclei to form cloud droplets or ice crystals.[45] This process requires sufficient humidity and lift mechanisms such as convection or frontal lifting to initiate supersaturation. Globally, clouds cover approximately 68% of Earth's surface, with maxima in tropical regions driven by intense updrafts.[46] Clouds are classified by altitude, shape, and composition, with foundational categories established by Luke Howard in 1803: cumulus (puffy, associated with convective updrafts from surface heating), stratus (layered sheets from stable, widespread lifting), and cirrus (high-altitude wispy formations composed mainly of ice crystals).[47] Cumulus clouds develop vertically in unstable environments quantified by convective available potential energy (CAPE), a metric in joules per kilogram representing the integrated buoyant acceleration of an air parcel from the level of free convection to the equilibrium level.[48] Stratus clouds form horizontally in more uniform cooling scenarios, while cirrus occur above 6 km where temperatures drop below -40°C, favoring ice sublimation over liquid droplets.[49] Precipitation initiates within clouds via microphysical processes: in warm clouds (above 0°C), collision-coalescence where larger droplets fall and collect smaller ones, growing to raindrop sizes observable via radar reflectivity profiles of drop size distributions.[50] In mixed-phase clouds (0°C to -40°C), the Bergeron-Findeisen process dominates, wherein ice crystals grow preferentially by vapor diffusion at the expense of supercooled liquid droplets due to lower saturation vapor pressure over ice, leading to snowflakes that may melt into rain upon descent.[51] Orographic lift contributes to localized cloud and precipitation formation when prevailing winds force moist air upslope over terrain, enhancing adiabatic cooling and condensation on windward slopes, while descending dry air on leeward sides creates rain shadows with reduced precipitation.[52] Radar data corroborates these mechanisms by detecting enhanced echo tops and precipitation rates correlating with terrain elevation.[50]Winds and Air Masses

Air masses are large bodies of air with relatively uniform temperature and humidity characteristics, formed over source regions where atmospheric conditions remain stable for extended periods.[53] Classifications include continental polar (cP), which originates over cold, dry landmasses in high latitudes and features low temperatures and minimal moisture; and maritime tropical (mT), which develops over warm ocean waters in subtropical regions, resulting in high temperatures and abundant humidity.[53] [54] These properties arise from radiative cooling or heating at the surface, leading to density contrasts that drive atmospheric motion when air masses interact.[53] Fronts represent the transitional zones or boundaries between differing air masses, where sharp gradients in temperature, density, and moisture create horizontal pressure differences that generate winds.[55] A cold front occurs when denser, cooler air advances under warmer air, steepening the pressure gradient and producing stronger winds along the boundary, while a warm front involves lighter, warmer air overriding cooler air, often with gentler slopes but sustained flow due to buoyancy forces.[56] These interactions establish geostrophic balance, where wind speeds align parallel to isobars, proportional to the pressure gradient force as described by the equation , with as geostrophic wind speed, as air density, as the Coriolis parameter, and as the pressure gradient perpendicular to the flow.[57] Synoptic charts depict these dynamics through isobars—lines of constant sea-level pressure—that reveal wind patterns; closely spaced isobars indicate steep gradients and high wind speeds, as air accelerates from high- to low-pressure areas to equalize imbalances caused by air mass contrasts.[58] For instance, a typical mid-latitude cyclone on such charts shows pressure troughs aligned with fronts, where southerly winds ahead of a warm front and northerly winds behind a cold front result from the cyclonic curvature and thermal contrasts between polar and tropical air masses.[59] Upper-level winds, such as jet streams, form near the tropopause due to strong temperature gradients between tropical and polar air masses, with core speeds often reaching 200-300 km/h (approximately 110-165 knots) in the subtropics and polar jets.[60] These fast zonal flows, driven by conservation of angular momentum and thermal wind shear, steer surface weather systems by modulating divergence aloft and influencing the positioning of upper-level ridges and troughs.[60] Katabatic winds, conversely, arise from localized gravity drainage, where cold, dense air flows downslope from elevated plateaus or glaciers under the influence of buoyancy forces, accelerating as potential energy converts to kinetic energy, often exceeding 100 km/h in Antarctica's coastal regions.[61] During the 1930s Dust Bowl in the U.S. Great Plains, prolonged drought intensified surface heating and reduced vegetation, amplifying meridional temperature gradients and pressure differences that fueled sustained high-speed winds, with gusts up to 100 km/h eroding exposed soils under strong synoptic-scale forcings like the Great Dakotas Storm of November 1930.[62] 30101-0/fulltext) These events exemplified how land-atmosphere feedbacks exacerbated existing air mass contrasts, leading to persistent southerly flows that transported dry continental tropical air northward, sustaining the anomalous wind regime.[63]Storms and Convective Systems

Storms and convective systems represent organized manifestations of atmospheric instability, where vertical motion driven by buoyancy and shear generates intense weather phenomena, including tropical cyclones and severe thunderstorms. These systems arise from the interaction of convective available potential energy (CAPE), typically exceeding 2000 J/kg in severe cases, and low-level vorticity, which amplifies rotation through stretching and tilting mechanisms.[64][65] Empirical observations indicate that such systems produce the majority of severe weather hazards, with global occurrences tied to regional thermodynamics rather than long-term intensification trends unsupported by reanalyses.[66] Tropical cyclones form over warm ocean surfaces where sea surface temperatures exceed 26.5°C (80°F) to 27°C, enabling sufficient latent heat release from evaporation to fuel sustained convection and low-level inflow.[67][68] The Coriolis effect, requiring latitudes poleward of about 5° for adequate rotational force, initiates cyclonic vorticity, preventing filling of the low-pressure core and allowing organization into a symmetric vortex.[69] Globally, approximately 80 to 100 tropical cyclones develop annually, with roughly half intensifying to hurricane strength, based on historical satellite and reanalysis data spanning decades.[70] Intensity is categorized via the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which rates storms from Category 1 (sustained winds 119-153 km/h) to Category 5 (winds ≥252 km/h), focusing solely on maximum one-minute sustained wind speeds at 10 m altitude.[71] Peer-reviewed downscaling from climate reanalyses reveals no robust global increase in cyclone intensity metrics over the past century, with most showing weak or insignificant trends amid observational biases and natural variability.[66][72] Severe mid-latitude convective systems, such as supercells, emerge from supercellular updrafts exceeding 40 m/s, sustained by veering wind shear that separates updraft and downdraft regions, fostering persistent rotation via baroclinic generation of horizontal vorticity.[73][74] These storms produce large hail through particles recycled within the updraft, where supercooled water accretes on ice nuclei, growing to diameters over 5 cm before gravitational sorting ejects them.[75] Mesoscale convective systems (MCSs), spanning 100 to 1000 km, organize as ensembles of thunderstorms with lifetimes exceeding 6 hours, driven by cold pools that propagate leading-line convection and trailing stratiform precipitation.[76][77] Tornadoes within these systems require enhanced low-level vorticity, often >0.01 s⁻¹, stretched by intense updrafts in environments of high CAPE (>2500 J/kg) and 0-6 km bulk shear (>20 m/s), leading to mesocyclone descent and surface intensification.[64][78] Such metrics underscore causal links to local disequilibria rather than aggregated extremes, with reanalyses confirming stable frequencies without systematic escalation.[79]Observation Methods

Surface and Upper-Air Measurements

Surface weather observations rely on ground-based instruments designed to measure key atmospheric variables such as temperature, pressure, wind speed and direction, humidity, and precipitation, with strict adherence to international standards for calibration and siting to ensure data comparability. Thermometers, typically liquid-in-glass or electronic types, record air temperature within ventilated shelters like the Stevenson screen, a louvered wooden enclosure invented in 1864 that minimizes solar radiation errors and provides accurate readings by promoting airflow while blocking direct sunlight and precipitation.[80][81] Barometers, including mercury or aneroid varieties, gauge atmospheric pressure to detect fronts and storm systems, calibrated against standard sea-level references. Anemometers quantify wind speed via cup rotations or sonic methods, paired with wind vanes for direction, positioned at standard heights of 10 meters above ground to avoid terrain distortions.[82][83] Precipitation is captured using rain gauges, often funnel-shaped collectors with tipping buckets for automated measurement, fitted with wind shields such as the WMO-recommended pit or wedge types to counteract undercatch from turbulence, which can reduce accuracy by up to 20% in windy conditions without protection. Hygrometers assess relative humidity through psychrometric wet- and dry-bulb setups or capacitance sensors, integrated into comprehensive automated weather stations that log data at intervals as short as one minute. These instruments undergo regular calibration against traceable standards, as outlined in WMO guidelines, to maintain precision within 0.1–0.5°C for temperature and 1–5% for pressure, enabling long-term trend analysis despite evolving technology.[84][81] Upper-air measurements extend profiling above the surface using radiosondes, lightweight sensor packages attached to helium balloons that ascend to 30–35 km, transmitting real-time data on temperature, pressure, humidity, and winds via radio signals in the 400 MHz band. Launched twice daily at 0000 and 1200 UTC from over 1,000 global sites coordinated by the WMO, radiosondes rise at approximately 300 meters per minute, providing vertical profiles critical for initializing weather models and validating thermodynamic structures.[85][86] Modern systems incorporate GPS for precise wind derivation, with sensors calibrated pre-launch to achieve accuracies of 0.2–0.5°C in temperature and 2–5% in humidity, though challenges like balloon drift and sensor icing persist in cold, moist layers.[85] The World Meteorological Organization's Global Observing System encompasses approximately 17,500 surface stations and platforms, including synoptic land sites that form the backbone of baseline observations dating to the 1850s, when systematic networks emerged in Europe and North America for daily records of pressure and temperature. These legacy datasets, from stations like those in the Smithsonian's early networks, support climate monitoring by preserving continuity amid urbanization and instrumental upgrades, with WMO centennial stations—now numbering 475—offering unbroken series exceeding 100 years for empirical validation of long-term variability.[87][88][89]| Instrument | Primary Variable | Calibration/Protection Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Thermometer | Air temperature | Stevenson screen for radiation shielding; ±0.1–0.5°C accuracy[80] |

| Barometer | Atmospheric pressure | Traceable to mercury standards; ±0.1–1 hPa[82] |

| Anemometer | Wind speed | 10 m height exposure; ±0.5 m/s[83] |

| Rain Gauge | Precipitation amount | Wind shield to minimize undercatch; automated tipping bucket[84] |

| Radiosonde (upper-air) | Vertical profiles of T, P, RH, wind | Pre-launch calibration; GPS wind tracking[85] |

Remote Sensing Technologies

Remote sensing technologies in meteorology involve the non-contact acquisition of atmospheric data using electromagnetic radiation across various spectra, enabling the detection of cloud properties, precipitation, winds, and aerosols from satellites and ground-based instruments. These methods leverage passive detection of emitted or reflected radiation and active transmission of signals, such as radar pulses, to infer meteorological variables. Space-based platforms provide broad coverage but often trade spatial resolution for temporal frequency, while ground-based systems offer higher local resolution at the expense of limited geographic extent.[90] Geostationary satellites like the GOES-R series, operated by NOAA, deliver continuous infrared imaging of cloud-top temperatures and atmospheric motion vectors over the Western Hemisphere, with the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) scanning full disks every 10-15 minutes at spatial resolutions of 0.5-2 km in visible and infrared bands.[91] This enables real-time monitoring of convective development but sacrifices finer detail compared to polar-orbiting systems due to the fixed vantage point at approximately 35,800 km altitude. In contrast, polar-orbiting satellites such as the Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS), which completes 14 orbits per day for twice-daily global coverage, provide higher-resolution soundings of temperature, humidity, and cloud properties using instruments like the Cross-track Infrared Sounder (CrIS) and Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder (ATMS), achieving vertical profiles with resolutions down to 1-2 km horizontally in select modes.[92] [93] Ground-based Doppler radars, deployed in networks like the U.S. NEXRAD system, excel in measuring radial velocity fields within storms through the Doppler shift of returned echoes from hydrometeors, resolving wind speeds to within 1 m/s at ranges up to 230 km with azimuthal resolutions of about 1 degree and range gates of 250 m.[94] [95] These systems offer superior spatial resolution near the site—often sub-kilometer—for detecting mesocyclones and shear but suffer from beam spreading and ground clutter at distance, limiting utility over complex terrain or beyond line-of-sight horizons, unlike space-based radars which maintain consistent geometry but coarser footprints (e.g., 5-25 km). Microwave remote sensing complements these by estimating precipitation rates via emission and scattering signatures; passive microwave imagers on satellites like those in the GPM constellation derive rain rates over oceans and land with accuracies of 0.5-2 mm/h, penetrating clouds opaque to visible/IR sensors.[96] [97] LIDAR systems, using laser pulses for active ranging, profile aerosol distributions and backscatter with vertical resolutions of 10-30 m up to 10-20 km altitude, aiding in the tracking of dust, smoke, and volcanic ash layers that influence radiative forcing and visibility.[98] Ground-based LIDARs provide high temporal resolution (seconds) for site-specific monitoring, while spaceborne variants like those on CALIPSO offer global context but with reduced vertical sampling due to orbital altitude. Recent advancements include 2024 CubeSat deployments, such as miniaturized precipitation radars and hyperspectral imagers, which enhance spatial resolutions below 1 km for targeted weather phenomena like hurricanes, enabling denser constellations for improved revisit times over traditional platforms.[99] These small satellites mitigate trade-offs by deploying in swarms, though challenges persist in power and data downlink for sustained operations.[100]Data Assimilation and Networks

Data assimilation integrates diverse observational data with short-range numerical model forecasts to produce an optimal estimate of the atmospheric state, minimizing uncertainties through statistical optimization techniques. This process addresses inconsistencies between sparse, noisy observations and model predictions by weighting inputs according to their error characteristics, enabling coherent initial conditions for weather prediction. In operational systems, it operates cyclically, typically every 6 to 12 hours, though some configurations incorporate hourly updates for select data streams.[101][102] Key methods include ensemble Kalman filters, which use ensembles of model states to propagate error covariances and update estimates sequentially, handling non-Gaussian errors prevalent in atmospheric dynamics. Global numerical weather prediction centers, such as the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), assimilate tens of millions of observations per assimilation cycle—drawing from surface pressures, radiosonde profiles, satellite radiances, and aircraft reports—to refine gridded analyses with resolutions down to kilometers. This yields reduced root-mean-square errors in initial states, with ensemble variants demonstrating superior performance over traditional variational approaches for convective-scale phenomena.[103][104][105] The World Meteorological Organization's Global Observing System (GOS), a core component of the Integrated Global Observing System, networks surface-based stations, marine buoys, aircraft, and polar-orbiting satellites to supply real-time data feeds. Over 17,500 surface platforms report essential variables like temperature and wind hourly, complemented by in-situ ocean and upper-air measurements, ensuring global coverage despite gaps in remote regions. Quality control precedes assimilation, involving automated screening for outliers and instrumental biases; for instance, variational bias correction schemes adjust satellite radiance observations for calibration drifts and viewing-angle effects. Reanalysis efforts, such as ECMWF's ERA5 dataset spanning 1940 to near-present, exemplify retrospective application, incorporating historical bias adjustments to homogenize long-term records while informing operational protocols.[87][106][107]Prediction and Modeling

Traditional Forecasting Techniques

Traditional weather forecasting relied on empirical observations, pattern recognition, and heuristic rules derived from historical data, predating computational models and emphasizing manual analysis of atmospheric patterns. Synoptic charts, which plot simultaneous weather observations to depict pressure systems and fronts, emerged in the mid-19th century following the advent of the telegraph, enabling coordinated data collection across regions. Dutch meteorologist Christoph Buys Ballot, founder of the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute in 1854, advanced this approach by issuing the first storm warnings in 1857 based on such charts and Buys Ballot's law, which relates wind direction to pressure gradients in the Northern Hemisphere.[108] These charts allowed forecasters to visualize isobars and isotherms, facilitating short-term predictions of storm tracks and pressure changes through manual extrapolation.[109] Basic techniques included persistence forecasting, which assumes current conditions will continue unchanged, and trend forecasting, which extrapolates ongoing changes at a constant rate. Persistence proves effective in stable weather regimes, such as prolonged fair conditions, where patterns evolve slowly, but fails during transitions.[110] Trend methods apply to steady-state phenomena, calculating future positions via distance equals rate times time, often used for tracking features like high-pressure ridges on synoptic maps.[111] Analog forecasting complemented these by identifying historical weather maps resembling current setups, then applying past outcomes to predict future evolution, relying on forecasters' experience to select comparable cases.[112] The Norwegian cyclone model, developed by the Bergen School in the 1910s and 1920s under Vilhelm Bjerknes, provided a structured framework for forecasting extratropical cyclone life cycles, emphasizing frontal boundaries and occlusion processes. This model describes cyclones forming along polar fronts, intensifying with warm and cold front separations, and weakening upon occlusion, enabling predictions of precipitation and wind shifts associated with frontal passages.[113] Forecasters applied it to synoptic charts to anticipate cyclone tracks and weather sequences, marking a shift toward dynamical understanding over purely empirical rules.[114] Despite their foundational role, traditional methods were inherently limited by their heuristic nature and sensitivity to chaotic atmospheric dynamics, where small initial perturbations amplify into divergent outcomes, undermining analog reliability. Finding exact historical analogs proved challenging due to incomplete data and unique combinations of variables, often leading to subjective biases in pattern matching.[115] These techniques excelled for short-range (up to 24-48 hours) forecasts in predictable regimes but struggled with long-term predictability, as atmospheric nonlinearity prevents precise extrapolation beyond inherent limits.[116]Numerical Weather Prediction Models

Numerical weather prediction (NWP) models computationally solve the governing equations of atmospheric dynamics and thermodynamics on discrete spatial grids to forecast future states from initial conditions. These equations, rooted in the Navier-Stokes equations for fluid motion, are simplified into primitive equations that express conservation of momentum, mass, energy, and water vapor, often under the hydrostatic approximation to reduce computational demands.[117] The atmosphere is discretized into a three-dimensional grid, typically with horizontal resolutions ranging from 10 to 50 kilometers globally and 50 to 100 vertical levels extending from the surface to the upper stratosphere.[118] Time-stepping schemes advance the solution forward in increments of minutes, integrating physical processes like advection and diffusion.[119] Sub-grid-scale phenomena, unresolved by the grid spacing—such as individual cloud droplets, convective updrafts, and turbulent eddies—are represented via parameterization schemes that statistically approximate their aggregate effects on larger-scale variables like temperature and wind. For instance, cumulus parameterization estimates vertical transport of heat and moisture from convection too small to resolve explicitly, while boundary-layer schemes model turbulence near the surface. Radiation schemes compute heating from solar and terrestrial fluxes, and microphysics parameterizations simulate precipitation formation. These approximations introduce unavoidable errors, as they rely on empirical relations tuned to observations rather than direct simulation.[118][120] Prominent global NWP systems include the U.S. Global Forecast System (GFS), operated by NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Prediction, which runs at approximately 13 km horizontal resolution and produces forecasts up to 16 days ahead, and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts' (ECMWF) Integrated Forecasting System (IFS), with deterministic runs at about 9 km resolution for enhanced detail in medium-range predictions.[121][122] To quantify uncertainty arising from initial condition errors and model imperfections, both employ ensemble prediction systems: the GFS Ensemble (GEFS) generates 30 perturbed members alongside its deterministic run, while ECMWF's Ensemble Prediction System (EPS) produces 50 members plus a control forecast.[123][122] The inherent predictability horizon of NWP stems from the atmosphere's chaotic dynamics, formalized by Edward Lorenz in 1963, who demonstrated through numerical experiments that infinitesimal perturbations in initial conditions amplify exponentially—a phenomenon termed the "butterfly effect" in popular accounts. This sensitivity limits deterministic skill to roughly 7-10 days for synoptic-scale features like mid-latitude cyclones, beyond which ensemble spreads dominate and forecasts revert to climatology. Operational verification confirms this ceiling, with anomaly correlations for 500 hPa geopotential height dropping below 60% skill around day 10.[124][125][126]Advances in Probabilistic and AI-Driven Forecasting

Ensemble prediction systems (EPS), introduced operationally in the 1990s but refined significantly post-2000, generate multiple forecasts from perturbed initial conditions and model physics to quantify uncertainty in weather predictions.[127] These systems have demonstrated substantial skill improvements, with continuous upgrades in data assimilation, observation usage, and model resolution leading to enhanced probabilistic outputs for medium-range forecasts.[128] For instance, ECMWF's ENS ensemble has evolved to provide reliable probability estimates, reducing errors in precipitation and temperature forecasts by incorporating stochastic perturbations.[129] Machine learning techniques, advancing since the early 2000s, have enabled better pattern detection in atmospheric data, complementing traditional ensembles with data-driven approaches.[126] Models like GraphCast, released by Google DeepMind in 2023, use graph neural networks trained on reanalysis data to produce 10-day global forecasts that outperform operational deterministic systems on 90% of verification targets, achieving higher accuracy in wind speeds and temperatures while requiring minutes of computation versus hours for physics-based simulations.[130][131] Similarly, GenCast, a 2024 probabilistic machine learning model, surpasses the ECMWF ENS in skill for medium-range ensemble forecasts by generating diverse weather scenarios efficiently.[132] In hurricane forecasting, the NOAA Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System (HAFS), enhanced with AI elements, accurately predicted rapid intensification for Hurricanes Helene and Milton in 2024, providing up to four days' advance notice of explosive deepening for Milton, which reached Category 5 status.[133][134] This performance stemmed from improved vortex initialization and high-resolution ensemble guidance, enabling better emergency response.[135] Despite these gains, AI-driven models face limitations, including their "black-box" nature, which obscures causal physical processes and hinders interpretability compared to numerical models grounded in atmospheric dynamics.[136] Training data biases toward historical patterns can lead to poorer performance on unprecedented extreme events, where numerical models retain advantages in RMSE for record-breaking temperatures.[137] Additionally, over-reliance on empirical correlations without embedded physics risks extrapolation failures in novel climate regimes.[138]Human Interventions

Historical Weather Modification Efforts

Early attempts at weather modification trace back to ancient rituals across cultures, where communities invoked supernatural intervention to influence precipitation. In North American indigenous traditions, rain dances performed by tribes such as the Hopi involved rhythmic movements and chants believed to summon storms, though no empirical evidence supports their efficacy beyond coincidental weather patterns.[139] Similarly, in ancient India, Vedic yajna rituals with mantras and offerings aimed to induce rainfall by appeasing deities, reflecting a pre-scientific reliance on spiritual causation rather than physical mechanisms. African rainmakers, including Zulu isanusi practitioners, conducted ceremonies connecting with ancestral spirits to control elements, often tied to seasonal droughts but lacking verifiable causal links to atmospheric changes.[140] Scientific weather modification emerged in the mid-20th century following laboratory discoveries of ice nucleation by dry ice and silver iodide. Project Cirrus, initiated in 1947 by General Electric and U.S. military sponsors, represented the first major effort, including the seeding of a hurricane on October 13 with 180 pounds of dry ice dropped into its eyewall to stimulate convection and dissipate it.[141] The operation correlated with the storm's unexpected path change toward Savannah, Georgia, causing $2 million in flood damage and prompting lawsuits against participants, after which hurricane seeding was halted due to inconclusive causation and liability risks. Over its five-year span, Project Cirrus refined seeding techniques with silver iodide and water but yielded limited scalable results from uncontrolled field tests.[142] In the Soviet Union, hail suppression programs expanded in the 1950s using ground-based cannons to generate shock waves intended to disrupt hailstone formation in convective clouds. Deployed across agricultural regions like the North Caucasus, these devices fired explosive charges to produce acoustic waves that theoretically fragmented supercooled droplets into rain rather than ice, protecting crops in hail-prone areas.[143] Evaluations of Soviet efforts, spanning decades, reported reductions in hail damage but suffered from inadequate randomized controls, with statistical analyses showing variable outcomes dependent on storm intensity.[144] During the Vietnam War, Operation Popeye (1967–1972) marked the first known combat use of weather modification, with U.S. Air Force C-130 aircraft dispersing silver and lead iodide into monsoon clouds over the Ho Chi Minh Trail to extend rainy seasons and impede enemy logistics.[145] The program, conducted in secrecy over Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, reportedly increased local rainfall by up to 30% in targeted zones, softening roads and delaying supply convoys, but its tactical impact was debated amid natural seasonal variability.[146] Revelations in 1974 led to the 1977 ENMOD Convention, prohibiting environmental modification for hostile purposes due to ethical concerns over unintended cross-border effects. China's weather modification for the 2008 Beijing Olympics exemplified large-scale application, with the Beijing Weather Modification Office firing over 1,100 rockets loaded with silver iodide from August 1–12 to seed and dissipate approaching rain clouds, ensuring dry conditions for outdoor events.[147] This effort, part of a broader arsenal including aircraft and artillery, successfully prevented precipitation during key ceremonies, though attribution relied on operational logs rather than comparative trials amid Beijing's variable summer weather.[148] Assessments of historical seeding trials by the World Meteorological Organization indicate marginal precipitation enhancements of 10–15% in localized orographic cloud experiments under controlled conditions, supported by statistical and observational data from glaciogenic seeding.[149] However, broader applications like hurricane or hail interventions often failed rigorous evaluation due to insufficient replication and confounding natural variability, underscoring persistent challenges in isolating seeding effects from baseline atmospheric dynamics.[150]Current Techniques and Applications

Cloud seeding represents the primary operational technique for localized weather modification, involving the dispersion of agents such as silver iodide into clouds to serve as artificial ice nuclei, facilitating the freezing of supercooled water droplets and subsequent precipitation formation through nucleation processes.[151] Silver iodide's crystalline structure closely resembles that of ice, enabling it to promote heterogeneous nucleation under conditions where natural nuclei are insufficient.[152] Dispersion occurs via aircraft-mounted flares or burners that release pyrotechnic mixtures during cloud penetration flights, or through ground-based generators that propel silver iodide smoke upwind of orographic clouds using propane combustion.[153] In the United States, western states including Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Idaho, and Nevada employ cloud seeding programs to augment winter snowpack in mountain ranges, targeting orographic clouds for enhanced snowfall that contributes to reservoir inflows.[154] Utah's program, operational since the 2022-2023 winter, incorporates both ground generators and aerial seeding with silver iodide to target winter storms over the Wasatch and Uinta ranges.[155] Similarly, Colorado's initiatives use remote-controlled ground units to release silver iodide during suitable storm conditions, focusing on watersheds supplying the Colorado River Basin.[156] The United Arab Emirates maintains an active cloud seeding operation through the National Center of Meteorology, utilizing aircraft to disperse silver iodide or hygroscopic salts like sodium chloride into convective clouds for rain enhancement and hail suppression, particularly over arid regions including Dubai.[157] Missions involve real-time radar monitoring to identify seedable clouds, with flights conducted from bases in Al Ain and Dubai, aiming to mitigate hail damage to infrastructure and agriculture while addressing chronic water shortages.[158] Emerging techniques include ionization-based methods, where ground- or aircraft-mounted ionizers generate charged particles to induce electrostatic attraction and coalescence of water droplets, potentially accelerating raindrop formation without chemical agents.[159] These systems employ corona discharge antennas or charge emitters integrated with seeding aircraft to alter droplet collision efficiencies via Coulomb forces, though applications remain largely experimental and integrated with traditional operations.[160]Scientific Efficacy and Ethical Debates