Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

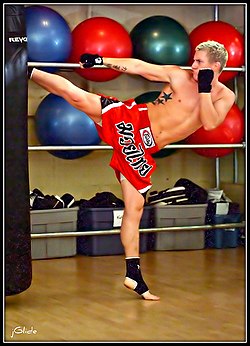

A kick is a physical strike using the leg, in unison usually with an area of the knee or lower using the foot, heel, tibia (shin), ball of the foot, blade of the foot, toes or knee (the latter is also known as a knee strike). This type of attack is used frequently by hooved animals as well as humans in the context of stand-up fighting. Kicks play a significant role in many forms of martial arts, such as capoeira, kalaripayattu, karate, kickboxing, kung fu, wing chun, MMA, Muay Thai, pankration, pradal serey, savate, sikaran, silat, taekwondo, vovinam, and Yaw-Yan. Kicks are a universal act of aggression among humans.

Kicking is also prominent from its use in many sports, especially those called football. The best known of these sports is association football, also known as soccer.

History

[edit]The English verb to kick appears in the late 14th century, meaning "to strike out with the foot", possibly as a loan from the Old Norse "kikna", meaning "bend backwards, sink at the knees".[1]

Kicks as an act of human aggression have likely existed worldwide since prehistory. However, the earliest documentation of high kicks, aimed above the waist or to the head, comes from East-Asian martial arts. Such kicks were introduced to the west in the 19th century with early hybrid martial arts inspired by East-Asian styles such as Bartitsu and Savate. Practice of high kicks became more universal in the second half of the 20th century with the more widespread development of hybrid styles such as kickboxing and eventually mixed martial arts.

The history of the high kick in Asian martial arts is difficult to trace. One theory was that it was developed in Northern Chinese Martial arts, in which techniques involving the use of the foot to strike the vital points of the head was often used. Another theory was that it was developed in the ancient Korean foot-fighting art of Taekyyon as a form of exercise and self-defense. The high kicks seen in Taekwondo today bear a resemblance to the kicks in Taekyyon. The high kick also seems to be prevalent in all traditional forms of Indochinese kickboxing, but these cannot be traced with any technical detail to pre-modern times. In Muay Boran ("ancient boxing" in Thailand) was developed under Rama V (r. 1868–1910) and while it is known that earlier forms of "boxing" existed during the Ayutthaya Kingdom, the details regarding these techniques are unclear. Some stances that look like low kicks, but not high kicks, are visible in the Shaolin temple frescoes, dated to the 17th century.[citation needed] The Mahabharata (4.13), an Indian epic compiled at some point before the 5th century AD, describes an unarmed hand-to-hand battle, including the sentence "and they gave each other violent kicks" (without providing any further detail). Kicks including ones above the waist are commonly depicted in the stone carvings of the Khmer Empire temples in Cambodia.

-

A kick delivered to a downed or falling enemy (a demon), Angkor period (c. 13th century) bas-relief at Banteay Chhmar in Cambodia.

-

A kick used in armed combat as a means of displacing the opponent's shield in historical European martial arts (Hans Talhoffer 1459)

-

A kick to the knee as depicted in a Baroque Ringen treatise (Johann Georg Passchen 1659)

-

Cambodian soldier uses a thrust kick to the chest of a Cham soldier. Thrust kicks are still used in pradal serey matches today. Bas-relief at the Banteay Chhmar(12th/13th century).

Applications

[edit]As the human leg is longer and stronger than the arm, kicks are generally used to keep an opponent at a distance, surprise them with their range and inflict substantial damage. Stance is also very important in any combat system and any attempt to deliver a kick will necessarily compromise stability to some degree. The application of kicks is a trade-off between the power and range that can be delivered against the cost incurred to balance. As combat situations are fluid, understanding this trade-off and making the appropriate decision to adjust to each moment is key.

Kicks are commonly directed against helpless or downed targets, while for more general self-defense applications, the consensus is that simple kicks aimed at vulnerable targets below the chest may be highly efficient, but should be executed with a degree of care. Self-defense experts, such as author and teacher Marc Macyoung, claim that kicks should be aimed no higher than the waist/stomach. Thus, the fighter should not compromise their balance while delivering a kick and retract the leg properly to avoid grappling. It is often recommended to build and drill simple combinations that involve attacking different levels of an opponent. A common example would be distracting an opponent's focus via a fake jab, following up with a powerful attack at the opponent's legs and punching.

Further, since low kicks are inherently quicker and harder to see and dodge in general they are often emphasized in a street fight scenario.

Practicality of high kicks

[edit]

The utility of high kicks (above chest level) has been debated.[2] Proponents have viewed that some high front snap kicks are effective for striking the face or throat, particularly against charging opponents and flying kicks can be effective to scare off attackers.[citation needed] Martial arts systems that utilize high kicks also emphasize training of very efficient and technically perfected forms of kicks, include recovery techniques in the event of a miss or block and will employ a wide repertoire of kicks adapted to specific situations.

Detractors have asserted that the flying/jumping kicks performed in synthesis styles are primarily performed for conditioning or aesthetic reasons, while the high kicks as practiced in sport martial arts are privileged due to specialized tournament rules, such as limiting the contest to stand-up fighting, or reducing the penalty resulting from a failed attempt at delivering a kick.

Although kicks can result in an easy takedown for the opponent if they are caught or the resulting imbalance is exploited, kicks to all parts of the body are very present in mixed martial arts, with some fighters employing them sporadically, while others, like Lyoto Machida, Edson Barboza and Donald Cerrone rely heavily on their use and have multiple knockouts by kicks on their resume.

Basic kicks

[edit]Roundhouse

[edit]

The attacker swings their leg sideways in a circular motion, kicking the opponent's side with the front of the leg, usually with the instep, ball of the foot, toe, or shin. It can also be performed is a 360-degree kick where the attacker performs a full circle with their leg, in which the striking surface is generally either the instep, shin or ball of the foot.[3]

There are many variations of the roundhouse kick based on various chambering of the cocked leg (small, or full, or universal or no chambering) or various footwork possibilities (rear-leg, front-leg, hopping, switch, oblique, dropping, ground spin-back or full 360 spin-back). An important variation is the downward roundhouse kick, nicknamed the "Brazilian kick" from recent K-1 use: A more pronounced twist of the hips allows for a downward end of the trajectory of the kick that is very deceiving.[4]

Due to its power, the roundhouse kick may also be performed at low level against targets, such as the knees, calf, or even thigh, since attacking leg muscles will often cripple an opponent's mobility. It is the most commonly used kick in kickboxing due to its power and ease of use. In most Karate styles, the instep is used to strike, though use of the shin as an official technique for a street fight would mostly be allowed.

Front

[edit]

Delivering a front kick involves raising the knee and foot of the striking leg to the desired height and extending the leg to contact the target. The strike is usually delivered by the ball of the foot for a forward kick or the top of the toes for an upward kick. Taekwondo practitioners utilize both the heel and ball of the foot for striking. Various combat systems teach "general" front kicks using the heel or whole foot when footwear is on. Depending on the fighter's tactical needs, a front kick may involve more or less body motion and thrusting with the hips is a common method of increasing both reach and power of the kick. The front kick is typically executed with the upper body straight and balanced. Front kicks are typically aimed at targets below the chest: stomach, thighs, groin, knees or lower. Highly skilled martial artists are often capable of striking head-level targets with front kicks.[5][6]

Side

[edit]

This kick is native to traditional Chinese martial arts, along with Taekyyon, Taekwondo and Karate. A side kick is delivered sideways in relation to the body of the person kicking.[7] A standard side kick is performed by first "chambering" by raising the kicking leg diagonally across the body, then extending the leg in a linear fashion toward the target, while flexing the abdominals. The two common impact points in sidekicks are the heel or the outer edge of the foot, with the heel is more suited to hard targets such as the ribs, stomach, jaw, temple and chest. When executing a side kick with the heel, the toes should be pulled back so that they only make contact the heel and not with the whole foot as striking with the arch or the ball of the foot can injure the foot or break an ankle.

Another way of doing the side kick is to make it a result of a faked roundhouse. This technique is considered antiquated[citation needed] and used only after an opponent is persuaded to believe it is a roundhouse (a feint) and then led to believe that closing the distance is best for an upper body attack, which plays into the tactical position and relative requirement of this version of the side kick. In Chinese, this is known as cè chuài(侧踹). In Korean, it is known as yeop chagi and in Okinawan fighting, it is sometimes called a "dragon kick". Some have called this side kick a "twist kick" due to its roundhouse like origins. This side kick begins as would a roundhouse kick however the practitioner allows the heel to move towards the center of the body. The kick is then directed outward from a cross-leg chamber so that the final destination of the kick is a target to the side, rather than one that is directly ahead.

Back

[edit]

Also referred to as a donkey kick, mule kick, horse kick or turning back kick. This kick is directed backwards, keeping the kicking leg close to the standing leg and using the heel as a striking surface. In wushu, this kick is called the "half-moon" kick but involves the slight arching of the back and a higher lift of the leg to give a larger curvature. It is often used to strike opponents by surprise when facing away from them.

Advanced kicks

[edit]These are often complicated variations of basic kicks, either with a different target or combined with another move, such as jumping.

Axe

[edit]

In Japanese, kakato-geri or kakato-otoshi; in Korean, doki bal chagi or naeryeo chagi or chikka chagi. In Chinese, pigua tui or xiapi tui.

An axe kick, also known as a hammer kick or stretch kick, is characterized by a straightened leg with the heel descending onto an opponent like the blade of an axe. It begins with one foot rising upward as in a crescent kick[8] then the upward arc motion is stopped and then the attacking foot is lowered to strike the target from above. The arc can be performed in either an inward (counter-clockwise) or outward (clockwise) fashion.

A well-known proponent of the axe kick was Andy Hug, the Swiss Kyokushinkai Karateka who won the 1996 K-1 Grand Prix.

Butterfly

[edit]

A butterfly kick is done by doing a large circular motion with both feet in succession, making the combatant airborne. There are many variations of this kick. The kick may look like a slanted aerial cartwheeland at the same time, the body spins horizontally in a circle. It begins as a jump with one leg while kicking with the other, then move the kicking leg down and the jumping leg up into a kick, landing with the first kicking leg, all while spinning. This kick involves arching the back when airborne to give a horizontal body with high angled legs striking horizontally. It may also resemble a jumping spin roundhouse kick (developed by James "Two Screens" Perkins) into a spinning hook kick, all in one jump and one spin although the difference is that both legs remain in the air at the same time for a considerable amount of time.[9]

First practiced in Chinese martial arts, the butterfly kick, or "xuan zi", is widely viewed as ineffective for actual combat. However, its original purpose was to evade an opponent's floor sweep and flip to the antagonist's exposed side or it may be used as a double aerial kick to an opponent standing off to the side. It is now widely used in demonstrative wushu forms (taolu) as a symbol of difficulty. Also note the similarity in execution when compared to an ice skating maneuver known as a flying camel spin (aka Button camel).

Calf

[edit]This strike is a low roundhouse kick that hits the backside of the calf with the shin.[10] While a calf kick sacrifices range in comparison to a standard low roundhouse kick to the thigh, it can not be checked with a knee or grabbed with an arm making it a safer kick for a striker in MMA matches versus opponents capable of checking low kicks or grapplers looking for takedown opportunities.[11] The kick was popularized by former UFC lightweight champion Benson Henderson.[12]

Crescent

[edit]

The crescent kick, also referred to as a "swing" kick and bandal chagi (반달 차기) in Korean, has some similarities to a hook kick and is sometimes practised as an off-target front snap kick.[13] The leg is bent like the front kick, but the knee is pointed at a target to the left or right of the true target. The energy from the snap is then redirected, whipping the leg into an arc and hitting the target from the side. This is useful for getting inside defenses and striking the side of the head or for knocking down hands to follow up with a close attack. In many styles of tai chi and Kalaripayattu, crescent kicks are taught as tripping techniques. When training for crescent kicks, it is common to keep the knee extended to increase the difficulty. This also increases the momentum of the foot and can generate more force, though it takes longer to build up the speed.[14]

The inward, inner, or inside crescent hits with the inside edge of the foot. Its arch is clockwise for the left leg and counter-clockwise for the right leg with force generated by both legs' movement towards from the midline of the body. The inward variant has also been called a hangetsu geri (half-moon kick) in karate and is employed to "wipe" an opponent's hand off of the wrist. It can quickly be followed up by a low side-blade kick to the knee of the offender.

The outward, outer, or outside crescent hits with the "blade", the outside edge of the foot. Its path is counter-clockwise for the left leg and clockwise for the right leg and force is generated by both legs' hip abduction. This is similar to a rising side kick, only with the kicking leg's hip flexed so that the line of force travels parallel to the ground from front to side rather than straight up, beginning and ending at the side.

Hook

[edit]

A hook kick or huryeo chagi (후려 차기) or golcho chagi in Korean, strikes with the heel from the side. It is executed similar to a side kick. However, the kick is intentionally aimed slightly off target in the direction of the kicking foot's toes. At full extension, the knee is bent and the foot snapped to the side, impacting the target with the heel. In taekwondo it is often used at the resulting miss of a short slide side kick to the head, but is considered a very high level technique in said circumstance. Practitioners of jeet kune do frequently use the term heel hook kick or sweep kick.[15][16][17] It is known as "gancho" in capoeira.

There are many variations of the hook kick, generally based on different foot work: rear- or front-leg, oblique or half-pivot, dropping, spin-back and more. The hook kick can be delivered with a near-straight leg at impact, or with a hooked finish (kake in Japanese karate) where the leg bends before impact to catch the target from behind. An important variation is the downward hook kick, delivered as a regular or a spin-back kick, in which the end of the trajectory is diagonally downwards for a surprise effect or following an evading opponent. Another important variation is the whip kick, which strikes with the flat of the foot instead of heel.[18]

The hook kick is mainly used to strike the jaw area of an opponent, but is also highly effective in the temple region.

L

[edit]An L-kick, also called aú batido, is a movement in breakdancing, capoeira and other martial arts and dance forms. It is executed by throwing the body into a cartwheel motion, but rather than completing the wheel, the body flexes while supported by one hand on the ground. One leg is brought downwards and forwards in a kicking motion while the other remains in the air (giving rise to the name).

Reverse roundhouse/wheel

[edit]

In Japanese, ushiro mawashi geri (後ろ回し蹴り); in Korean, bandae dollyo chagi (반대 돌려 차기), dwit hu ryo chagi, nakkio mom dollyo chagi or parryo chagi.

This kick is also known as a "heel kick", "turning kick", "reverse round kick", "spinning hook kick", "spin kick", or "wheel kick".[19] A low reverse roundhouse is also known as a "sweep kick" or "sitting spin kick", however, in some martial arts circles, when aimed at a downward angle to the anterior side of the knee it is commonly referred to as a "shark kick" due to its tendency to tear the anterior cruciate ligament. A reverse roundhouse kick traditionally uses the protruding point on the backside of the heel to strike with, the kicking leg coming from around the kicker's back as they pivot and the knee remaining relatively straight on the follow through, unlike the leg position in a reverse hooking kick, despite the spinning motion and the part of the heel being roughly the same. Variations exist for low, middle and high heights. Spinning and leaping variations of the kick are also popular and are often showcased in film and television media. At UFC 142, Edson Barboza knocked out Terry Etim using a wheel kick in the third round of their fight, the first such in the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

A similarly named but technically different kick, is the roundhouse kick performed by turning as if for a back straight kick and executing a roundhouse kick. It is known as a "reverse roundhouse kick" because the kicker turns in the opposite, or "reverse", direction before the kick is executed. This kick strikes with the ball of the foot for power or the top of the foot for range. This was exhibited by Bruce Lee on numerous occasions in his films Enter the Dragon, Fist of Fury and The Big Boss. Bill Wallace was also a great user of this kick, as seen in his fight with Bill Briggs, where he knocked his opponent out with the clocked 60 mph kick.[20] The jump spin hook kick was popularized in the mid-eighties by Steven Ho in open martial art competitions.

In Olympic format (sport) taekwondo, this technique is performed using the balls of the feet and in a manner similar to a back thrust, rather than the circular technique adopted in other styles of martial arts.

Flying

[edit]A flying kick, in martial arts, is a general description of kicks that involve a running start, jump, then a kick in mid-air.[21] Compared to a regular kick, the user is able to achieve greater momentum from the run at the start. Flying kicks are not to be mistaken for jumping kicks, which are similar maneuvers. A jumping kick is very similar to a flying kick, except that it lacks the running start and the user simply jumps and kicks from a stationary position.[22] Flying kicks are often derived from the basic kicks.[23] Some of the more commonly known flying kicks are the: flying side kick, flying back kick and the flying roundhouse kick, as well as the flying reverse roundhouse kick.[24] Flying kicks are commonly practiced in Taekwondo, Karate, Wushu and Muay Thai for fitness, exhibitions and competition. It is known as tobi geri in Japanese martial arts and twyo chagi in Taekwondo.

Showtime

[edit]The showtime kick gained notability after being used by mixed martial artist Anthony Pettis, during his fight against Benson Henderson on December 16, at WEC 53 for the WEC Lightweight Championship.[25] In the fifth round Pettis ran up the cage, jumped off the cage, then landed a switch kick while airborne. Sports reporters later named this the "showtime kick".[26] The kick was also used by mixed martial artists: Zabit Magomedsharipov[27] and others. The kick was featured in the movie Here Comes the Boom.

Scissor

[edit]Several kicks may be called a scissor kick, involving swinging out the legs to kick multiple targets or using the legs to take down an opponent.

The popularized version of a scissor kick is, while lying down, or jumping, the kicker brings both legs to both sides of the opponent's legs or to their body and head, then brings both in as a take down (as the name states, leg motions are like that of a pair of scissors).

The scissor kick in Taekwondo is called kawi chagi. In capoeira it is called tesoura (scissors).

Scissor kicks and other variants are also commonly applied in Vovinam.

Spinning heel

[edit]

A spinning heel kick is where the artist turns their body 360 degrees before landing the heel or the ball of their foot on the target. It is found in Muay Thai and is known in Capoeira as armada.

Vertical (thrust, push, and side)

[edit]A vertical kick involves bringing the knee forward and across the chest, then swinging the hip while extending the kicking leg outward, striking with the outside ("sword") edge of the foot. In karate this is called a yoko geri keage, in Taekwondo it is referred to as sewo chagi and can be performed as either an inward (anuro) or outward (bakuro) kick.

Multiple/machine gun

[edit]In Japanese karate, the term ren geri is used for several kicks performed in succession. Old karate did not promote the use of the legs for weapons as much as modern karate does, seeing them as being too open for countering, in modern sport karate (non-traditional) competitions, however, the ability to use multiple kicks without setting the foot down has become a viable option, not only for effectiveness but also for stylish aesthetics.

In taekwondo, three types of multiple kick are distinguished:

- Double kick (i-jung chagi): two kicks of the same type executed in succession by the same foot in the same direction.

- Consecutive kick (yonsok chagi): two or more kicks executed in succession by the same foot but in different directions, or with different attacking tools.

- Combination kick (honhap chagi): two or more kicks executed in succession by both feet.

One such multiple kick commonly seen in taekwondo, is a somewhat complex side kick where a high side kick is followed by a low side kick which is in turn followed by a more powerful side kick.[28] This combination is done rapidly and is meant not for multiple targets but for a single one. A multiple kick usually targets the face, thigh and chest, but in turn can be a multiple chest attack which is useful for knocking the breath out of an attacker. A multiple kick is usually involves shooting the leg forward as in a front kick and then pivoting and turning so as to actually deliver a side kick. That style has far less power but is much faster and more deceptive, which is what the multiple kick was designed for. The multiple kick, unlike some side or side blade kicks, never uses the outer edge of the foot; it is intended solely for the heel to be used as the impact point. Depending on the strength and skill of the attacker and the attacked, the combination can be highly effective or highly ineffective when compared to more pragmatic attacks. In some encounters with highly trained and conditioned fighters, multiple side-kicks have seen disastrous results against the abs of their target.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "kick | Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ "Kicking is starting to impact MMA striking". Bloody Elbow. 13 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-01-13. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "UFC 143 Judo Chop: The Instep Roundhouse Kick Of Stephen Thompson". Bloody Elbow. 6 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2014-01-13. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ The Essential Book of Martial Arts Kicks: 89 Kicks from Karate, Taekwondo, Muay Thai, Jeet Kune Do, and Others by Marc De Bremaeker and Roy Faige

- ^ Breen, Andrew (2013-04-29). "The Front Kick: How to Do It, When to Use It, What to Destroy With It (Part 1) – - Black Belt". Blackbeltmag.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "Judo Chop: Front Kicks With Lyoto Machida, Anderson Silva, Josh Thomson". Bloody Elbow. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "UFC Macau Judo Chop: Anderson Silva, Cung Le, Bruce Lee and the Side Kick". Bloody Elbow. 27 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "Judo Chop: Mirko "Cro Cop" Filipovic Unleashes an Axe Kick on Pat Barry". Bloody Elbow. 16 June 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "Shaolin Kung Fu Stretches & Moves : Butterfly Kick in Shaolin Kung Fu". YouTube. 2008-04-10. Archived from the original on 2010-10-03. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "Getting Technical on Calf Kicks". m.sherdog.com. Archived from the original on 2020-07-07. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- ^ "Dossier: Anatomy of the Calf Kick". Sherdog. Archived from the original on 2022-11-17. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ Dundas, Chad. "Rise of the calf kick: How a forgotten technique became MMA's hottest strike". The Athletic. Archived from the original on 2022-11-17. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ "Kicks Aren't Going Anywhere Part 2: Katsunori Kikuno". Bleacher Report. 2014-01-02. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "Judo Chop: Katsunori Kikuno Puts the Crescent Kick To Work on Kuniyoshi Hironaka at DREAM.13". Bloody Elbow. 5 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "Technique Talk: Henri Hooft on the rise of spinning kicks and attacks in mixed martial arts". MMA Fighting. 21 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-01-14. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "Taekwondo Kicks : Taekwondo Reverse Hook Kick". YouTube. 2008-06-24. Archived from the original on 2014-06-24. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "UFC 165 Judo Chop: Chris Clement's Spinning Sweep Kick". Bloody Elbow. 24 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "Hook Kick - Martial Arts Technique". Archived from the original on 2019-05-11. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "UFN 31 Judo Chop: Rustam Khabilov's Spinning Hook Kick". Bloody Elbow. 11 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-01-22. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- ^ "FightBack Live with Bill Wallace". Black Belt Magazine. 2020-05-06. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ^ Advanced Dynamic Kicks. Black Belt Communications. 1986. ISBN 9780897501293. Archived from the original on 2023-04-25. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "Black Belt". Active Interest Media, Inc. October 17, 1988. Archived from the original on May 13, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Black Belt". Active Interest Media, Inc. October 17, 1986. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Black Belt". Active Interest Media, Inc. February 17, 1991. Archived from the original on May 13, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Martin, Damon (September 23, 2010). "HENDERSON VS. PETTIS OFFICIAL FOR WEC DEC 16". MMAweekly.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Ciccarelli, Mitch (December 17, 2011). "Anthony Pettis' Kick and the Best Finishing Moves in MMA History". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ "Watch: UFC Prospect Hits Sensational 'Showtime Kick', Scores Finish, Calls Out Artem Lobov - Pundit Arena". www.punditarena.com. September 3, 2017. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ "Black Belt". Active Interest Media, Inc. October 17, 1988. Archived from the original on May 13, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2022 – via Google Books.

External links

[edit]Fundamentals

Definition and Purpose

A kick in martial arts is defined as a percussive striking technique executed primarily with the leg, foot, or knee, setting it apart from upper-body punches or grappling maneuvers that emphasize holds and throws.[4] This method leverages the body's lower extremities for impact, utilizing areas such as the heel, ball of the foot, shin, or knee to deliver force.[4] The primary purposes of kicks encompass offensive power generation, enabled by the superior strength of leg muscles over arm muscles; establishing or restoring distance in combat; unbalancing opponents to create openings; and precisely targeting vulnerabilities like the head, torso, or lower limbs.[4] For instance, low kicks can impair mobility by striking the legs, while high kicks aim to concuss or disorient.[5] Kicks have been central to unarmed combat systems worldwide, such as karate, taekwondo, and Muay Thai, where they embody cultural and practical significance. Fundamentally, a kick consists of chambering, where the knee lifts to coil potential energy; extension, thrusting the limb to maximize impact velocity; and retraction, swiftly withdrawing to evade counters and reset stance.[6] These phases optimize efficiency in various disciplines.Biomechanics

The biomechanics of effective kicking in martial arts relies on coordinated hip rotation and torque generation to maximize power and precision. Hip rotation serves as the primary driver, with rapid pelvic axial rotation initiating the motion and transferring rotational energy from the torso to the lower body.[7] Torque is generated through hip abduction and knee extension, often at angular velocities exceeding 700 degrees per second, enabling efficient linear momentum transfer from the body's core to the striking limb.[7] Angular velocity in leg swings further enhances strike speed, with elite practitioners achieving foot velocities of 7-12 m/s, depending on the kick type and expertise level.[8] Key muscle groups and joint actions underpin these dynamics. The quadriceps, particularly the rectus femoris, drive knee extension and provide sustained force during the kicking phase, showing peak activation early in the motion.[9] Gluteus maximus contributes to hip power and stability, activating later to support retraction and overall propulsion.[9] Hip flexors and abductors initiate the swing, while hamstrings assist in control; joint actions like hip flexion and knee lock ensure a rigid structure for optimal energy transfer without collapse.[7] From a physics perspective, the destructive potential of a kick stems from its kinetic energy, calculated aswhere represents the effective mass of the kicking leg and is the impact velocity. This quadratic relationship emphasizes velocity's outsized role, as doubling speed quadruples energy output; for instance, velocities around 10 m/s can yield energies sufficient to fracture boards (approximately 5 J minimum). Leg length provides additional leverage, acting as an extended lever arm that amplifies torque and angular momentum in rotational kicks, with studies showing positive correlations between limb length and kick speed in side kicks. Maintaining balance and stability is crucial, primarily through strategic base leg positioning that creates a stable pivot against ground reaction forces. The support leg absorbs and redirects these forces—up to 4 Nm/kg at the hip—preventing falls and enabling full bodyweight commitment to the strike, with mediolateral stability directly influencing overall kick velocity and accuracy.[10]