Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Qix | |

|---|---|

North American arcade flyer | |

| Developer | Taito America[a] |

| Publisher |

|

| Designers | Randy Pfeiffer Sandy Pfeiffer |

| Series | Qix |

| Platform | |

| Release | October 1981 |

| Genre | Puzzle |

| Modes | Single-player, multiplayer |

Qix[b] (/ˈkɪks/ KIKS[c]) is a 1981 puzzle video game developed by husband and wife team Randy and Sandy Pfeiffer and published by Taito America for arcades. Qix is one of a handful of games made by Taito's American division (another is Zoo Keeper).[11] At the start of each level, the playing field is a large, empty rectangle, containing the Qix, an abstract stick-like entity that performs graceful but unpredictable motions within the confines of the rectangle. The objective is to draw lines that close off parts of the rectangle to fill in a set amount of the playfield.

Qix was ported to the contemporary Atari 5200 (1982), Atari 8-bit computers (1983),[12] and Commodore 64 (1983), then was brought to a wide variety of systems in the late 1980s and early 1990s: MS-DOS (1989), Amiga (1989), another version for the C64 (1989), Apple IIGS (1990), Game Boy (1990), Nintendo Entertainment System (1991), and Atari Lynx (1991).

Multiple home and arcade sequels followed and the concept was widely cloned. In the Gals Panic series from Kaneko, each captured area is not filled with a color, but reveals part of an image of a woman; this itself had been cloned into erotic-oriented games based on the concept of Qix.

Gameplay

[edit]

Controls consist of a four-direction joystick and two buttons: "Slow Draw" and "Fast Draw".

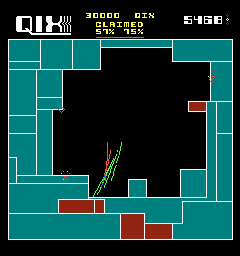

The player controls a diamond-shaped marker that initially moves along the edges of the playfield. Holding down one of the draw buttons allows the marker to draw a line (Stix) in unclaimed territory in an attempt to create a closed shape. Once an area is captured, it is filled with color and points are awarded based on the area claimed and drawing speed. Areas captured entirely with Slow Draw (orange-red in the screenshot) are worth double. The titular Qix is a colorful geometric figure in constant and random motion. The Qix will not actively seek out the marker, and it will not harm the marker if it collides with it while the marker is traversing the edge of the playfield or of any captured area. However, if the Qix collides with the marker as it is drawing a Stix before a new area is captured (or it touches the exposed Stix), one life is lost.

The marker cannot cross or backtrack along the line being drawn. If the marker stops while drawing, a fuse appears and burns along the line toward the marker; if it reaches the marker, the player loses one life. The fuse disappears once the marker is moved. If the player draws into a position where it cannot proceed any further, the fuse is triggered. The attract mode calls this a "Spiral Death Trap".

Sparx are enemies that traverse all playfield edges except unfinished Stix. A life is lost if one hits the marker. A meter at the top of the screen counts down to the release of additional Sparx and the mutation of all Sparx into Super Sparx, which can chase the marker along uncompleted Stix.

To complete a level, the player must claim a 75% percentage of the playfield (adjustable to be between 50% and 90%). If a level is completed by exceeding the minimum area percentage, a bonus is awarded for every 1% beyond the threshold.

Starting in level three, the player faces two Qixes. Splitting the playfield into two regions, each containing one Qix, ends the level. No immediate bonus is awarded for this, but a bonus multiplier is applied to the scoring in all subsequent levels. This multiplier starts at one before the first time that the Qix are split and increases by one for every additional splitting of the Qix, to a maximum of nine. Levels also add additional Sparx and the eventual appearance of only Super Sparx.

Reception

[edit]Upon release, Qix was a commercial hit. In 1983, Electronic Games reported that the game exceeded Taito's expectations, quickly rising to being one of the most popular titles of the year. The magazine attributes the game's success to it being unlike any other game at the time, specifically for its unique premise and gameplay mechanics. A year after its debut, its popularity declined and the game became largely forgotten. Keith Egging, Taito's "Director of Creativity",[15] told Electronic Games: "Qix was conceptually too mystifying for gamers. [...] It was impossible to master and once the novelty wore off, the game faded".[16] In Japan, it was the fifth highest-grossing arcade game of 1981.[17] The game has since been dubbed a sleeper hit.[18]

Qix and its home conversions have received largely positive reviews. The game was praised for its original concept and ideas, and has been described as a cultural phenomenon.[18] Video, who reviewed the Atari 5200 release, applauded its gameplay and bizarre yet interesting premise. They reported similar reactions from players, who enjoyed its mechanics and gameplay.[18] Video staff described the game as being a "cult phenomenon loved by a few and ignored by" more hardcore gamers. The home computer versions of Qix were praised by Russel Sipe of Computer Gaming World for its fascinating gameplay and for welcoming newcomers.[19] In How to Beat the Video Games Michael Blanchet said that 'Qix is probably the most complicated video game to emerge in years, yet its simplicity is beautiful. I think of it as electronic real estate. [...] Qix is a state of the art "Etch a Sketch."'[20]

Retrospective coverage of Qix has also been positive. AllGame's Brett Alan Weiss commended Qix for its addictive gameplay, technological accomplishments, and responsive controls. While he believed the graphics and sound effects were overly simplistic and crude, he said the game as a whole is "abstract minimalism at its videogame best".[13] Retro Gamer staff enjoyed Qix particularly for its addictive nature. They also compared its concept to that of the Etch A Sketch, a mechanical toy that allowed its user to draw straight lines across a small screen. The staff believed the game's simplicity was also one of its strong points, alongside its sound effects for being satisfying to hear.[21]

Accolades

[edit]At the 5th annual Arkie Awards in 1984, Qix received the Certificate of Merit in the category of "1984 Best Videogame Audio-Visual Effects (16K or more ROM)".[22] In 1995, Flux ranked the game 94th on their "Top 100 Video Games."[23] In 1997, the staff at Electronic Gaming Monthly listed the Nintendo Entertainment System version at #100 on their "100 Best Games of All Time" for its risk-versus-reward system and scoring.[24] The Killer List of Videogames listed it as #27 in their "Top 100 Video Games" list.[25]

Legacy

[edit]Sequels

[edit]Qix II: Tournament (1982) is a version of the original Qix with a new color scheme and which awards an extra life when 90% or more of the screen is enclosed.[26] Super Qix was released in 1987. The 1989 arcade video game Volfied, also known as Ultimate Qix (Genesis) or Qix Neo (PlayStation), was also released on several mobile phones. Another sequel, Twin Qix, reached a prototype stage in 1995, but was never commercially released.[26][27]

A port to the Game Boy developed by Minakuchi Engineering and published by Nintendo was released in 1990, with intermissions in which Mario, Luigi and Princess Peach have cameo appearances. In one, he is seen in a desert wearing Mexican clothing and playing a guitar with a vulture looking on.[28] The outfit later appears as a costume that Mario can wear in Super Mario Odyssey.[29] The Game Boy port was released as a Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console title in Japan on June 15, 2011,[30] and in North America and Europe on July 7.[31][32]

In 1999, a remake for the Game Boy Color was released called Qix Adventure. The player travels on a map screen, taking on opponents which appear on the playing field. Although optional, enclosing an opponent in the box opens a treasure chest, which can also be enclosed, giving the player an item.[33] Battle Qix was released for the PlayStation in 2002 by Success, under their Super 1500 Lite budget title series. It includes a remake of the original Qix alongside a competitive multiplayer mode.[34] Taito released a new version of Qix for the Xbox Live Arcade and PlayStation Portable Qix++ in December 2009.[35]

Clones

[edit]- Fill 'Er Up (1983, Atari 8-bit, ANALOG Computing)[36]

- Stix (1983, Commodore 64)[37]

- Styx (1983, IBM PC, Windmill Software)

- Frenzy (1984, Acorn Electron and BBC Micro, Micro Power)

- Xonix (1984, MS-DOS)

- Qiks (1984, Tandy Color Computer, Spectral Associates)[38]

- Quix (1984, Tandy Color Computer, Tom Mix Software)[39]

- Torch 2081 (1986, Amiga, Digital Concepts)[40]

- Zolyx (1987, Commodore 64, C16/Plus-4, Amstrad CPC, and ZX Spectrum, Firebird)[41]

- Maniax (1988, Atari ST, Amiga, Kingsoft)

- Gals Panic (1990, arcade, Kaneko), which started a subgenre of adult-themed "uncover the image" games.

- Cacoma Knight in Bizyland (1992-1993, Super NES/Famicom, Datam Polystar/Seta USA)

- Super Xonix (1996, IBM PC), a 2 player version

- Dancing Eyes (1996, arcade, Namco), a 3D version of the eroge subgenre, similar to Gals Panic

- Prometheus/Qrax (1997, Mac, Quarter Note Software)

- AirXonix (2000-2001, Windows, AxySoft)

- Qyx (2022, Atari 2600, Champ Games)[42][43]

In 2011, Den of Geek included Qix on a list of the top 10 most cloned video games.[44]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "クイックスアップライト筺体版" [Qix upright cabinet version]. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "クイックス TT テーブル筺体版" [Qix TT table cabinet version]. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Availability Update". The Video Game Update. Vol. 1, no. 11. February 1983. p. 16.

- ^ "Availability Update". The Video Game Update. Vol. 2, no. 1. April 1983. p. 16.

- ^ "Availability Update". Computer Entertainer. Vol. 8, no. 6. September 1989. p. 14.

- ^ "Availability Update". Computer Entertainer. Vol. 8, no. 8. November 1989. p. 14.

- ^ "Game Boy (original) Games" (PDF). Nintendo of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2016.

- ^ "GAMEBOY Software List 1989-1990". GAME Data Room (in Japanese). Archived from the original on August 27, 2018.

- ^ "NES Games" (PDF). Nintendo of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2014.

- ^ Qix North American promotional flyer. United States of America: Taito America Corporation. October 1981. Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "MobyGames: Game Browser: Games Developed By: Taito America Corporation". MobyGames. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ I Break for Arcadians: Good news, bad news - new games, joystick reviewed: Qix, By Joaquin Boaz, InfoWorld, 8 Aug 1983, Page 23

- ^ a b Alan Weiss, Brett (1998). "Qix - Review". AllGame. All Media. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Michael Brown, William (June 1983). "Qix - Atari/Atari 5200". Vol. 1, no. 8. Fun & Games Publishing. Electronic Fun with Computer & Games. p. 55. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Morgan, John (January 1, 2001). "The Story of Zoo Keeper". Giant List of Classic Game Programmers.

- ^ Pearl, Rick (June 1983). "Closet Classics". Electronic Games. p. 82. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ ""Donkey Kong" No.1 Of '81 — Game Machine's Survey Of "The Year's Best Three AM Machines" —" (PDF). Game Machine. No. 182. Amusement Press, Inc. February 15, 1982. p. 30.

- ^ a b c Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (November 1983). "Arcade Alley: Wintertime Winners". Video. 7 (8). Reese Communications: 38–39. ISSN 0147-8907.

- ^ Sipe, Russell (October 1989). "What Do You Do For Qix". Computer Gaming World. No. 64. p. 39.

- ^ Blanchet, Michael (1982). How to Beat the Video Games. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 54–60. ISBN 0671453750. p. 54:

Qix is probably the most complicated video game to emerge in years, yet its simplicity is beautiful. I think of it as electronic real estate. It may remind some of you of the old "connect the dots and claim the squares" game. Qix is a state of the art "Etch a Sketch."

- ^ Retro Gamer Staff (July 2, 2009). "Qix". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (January 1984). "Arcade Alley: The Arcade Awards, Part 1". Video. 7 (10). Reese Communications: 40–42. ISSN 0147-8907.

- ^ "Top 100 Video Games". Flux (4). Harris Publications: 32. April 1995.

- ^ "100 Best Games of All Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 100. Ziff Davis. November 1997. p. 102. Note: Contrary to the title, the intro to the article explicitly states that the list covers console video games only, meaning PC games and arcade games were not eligible.

- ^ McLemore, Greg; Staff, KLOV (2010). "The Top Coin-Operated Videogames of All Time". Killer List of Videogames. Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ a b Thomasson, Michael (November 2017). "Get Your Kicks From QIX". No. 1. Old School Gamer Magazine. pp. 20–21. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "Twin Qix - Videogame by Taito". Killer List of Videogames. International Arcade Museum. Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Orland, Kyle (February 4, 2011). "The Strange Career Path of Super Mario". 1UP.com. IGN. p. 18. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (June 13, 2017). "Super Mario Odyssey's Outfits Are A Nice Throwback". Kotaku. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ Bivens, Danny (June 15, 2011). "Japan eShop Round-Up (06/15/2011)". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ Langley, Ryan (July 7, 2011). "NA Nintendo Update - Fortified Zone, QIX, Roller Angels And More". GameSetWatch. UBM plc. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ Langley, Ryan (July 7, 2011). "EU Nintendo Update - QIX, Fortified Zone, ANIMA: Ark of Sinners And More". GameSetWatch. UBM plc. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ IGN Staff (November 16, 2000). "Qix Adventure". IGN. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "SuperLite 1500 シリーズ バトルクイックス (PS)". Famitsu (in Japanese). Kadokawa Corporation. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Hatfield, Daemon (December 9, 2009). "Qix++ Review". IGN. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Hudson, Tom (March 1983). "Fill 'Er Up". ANALOG Computing (10): 100.

- ^ Dillon, Roberto (2014). Ready: A Commodore 64 Retrospective. Springer. p. 141.

- ^ Boyle, L. Curtis. "Qiks".

- ^ Boyle, L. Curtis. "Quix".

- ^ "Torch 2081". Lemon Amiga.

- ^ "Zolyx". Lemon64.

- ^ "How Champ Games tricks old hardware with new cartridges on the Atari 2600".

- ^ "Champ Games".

- ^ Lambie, Ryan (May 6, 2011). "The top 10 most cloned video games". Den of Geek.

External links

[edit]Development and design

Creation and team

Qix was developed by husband-and-wife team Randy Pfeiffer and Sandy Pfeiffer through their newly founded company, Threshold Research Corporation, for publisher Taito America. Incorporated on December 22, 1980, Threshold Research specialized in arcade game development and produced Qix as one of its inaugural projects, marking it as one of the earliest titles developed for Taito America by an independent U.S. studio.[11] Randy Pfeiffer served as the primary programmer and designer, while Sandy Pfeiffer contributed to the game's concept and overall design. The core idea originated from Randy's programming demonstration of the fluid, serpentine movement of the titular Qix entity, which Sandy recognized as the foundation for an engaging puzzle mechanic, envisioning it as a "video-game Etch A Sketch." This breakthrough reportedly occurred during a casual moment involving vintage champagne in a jacuzzi, leading to the game's unique vector-style drawing gameplay.[12] The game's name derives from Randy's vanity license plate, "JUS4QIX," intended to convey "just for kicks," reflecting the playful yet innovative spirit of the project. Completed in 1981, Qix represented a departure from Taito's typical Japanese-developed titles, showcasing American ingenuity in arcade design during the early 1980s video game boom.[13][14]Innovative aspects

Qix introduced a groundbreaking approach to arcade gameplay by shifting focus from traditional action-oriented mechanics, such as shooting or platforming, to a puzzle-based system where players control a marker to draw lines and enclose areas of the screen, aiming to claim at least 75% of the playfield to advance levels. This territory-claiming mechanic, which rewarded strategic enclosure over direct confrontation, marked one of the earliest examples of abstract puzzle design in arcades, diverging significantly from the era's dominant titles like Pac-Man or Space Invaders.[2][6] A key innovation lay in the dual drawing modes—fast draw for quick, safer lines and slow draw for riskier, higher-scoring segments that filled enclosed areas with bonus red coloring—creating a tense risk-reward dynamic that demanded precise timing and spatial awareness to evade hazards like the Sparx, which patrolled the edges, and the Qix, an erratic, plasma-like entity that could burst through unfinished lines. This system not only heightened player engagement through escalating difficulty but also encouraged creative strategies, such as trapping the Qix in small sections for bonus points, setting a precedent for thoughtful decision-making in fast-paced environments.[2] Visually, Qix's minimalist, line-art aesthetic, rendered on Taito's custom hardware with a 6809 processor, evoked a sense of modern abstraction uncommon in 1981 arcades, using filled polygons and dynamic enemy movements to simulate organic, unpredictable threats without relying on character sprites or narratives. This design influenced a wave of similar "Qix-like" games, including clones such as Gals Panic and sequels like Volfied, demonstrating its lasting impact on the puzzle genre and proving arcade games could thrive on intellectual challenge rather than reflex alone.[2][6]Gameplay

Core mechanics

In Qix, the player controls a marker positioned on the perimeter of a rectangular playfield, using it to draw lines that enclose unoccupied areas and progressively claim territory from the central "Qix" entity. The core objective is to fill at least 75% of the playfield— the factory-default threshold—by completing such enclosures, after which the level advances and the claimed areas reset for the next screen. Enclosures must connect back to existing boundaries without intersecting the player's own trail, as crossing one's path results in an immediate loss of life. This mechanic emphasizes strategic line drawing, where smaller, safer enclosures build toward the quota gradually, while larger ones offer higher rewards but greater exposure to hazards.[15][2] Movement is handled via a 4-way joystick, allowing the marker to travel along the playfield's edges or previously drawn lines at a base speed. Two action buttons toggle between Fast Draw and Slow Draw modes: Fast Draw enables rapid line creation for evasion but yields standard scoring, whereas Slow Draw halves movement speed—making the marker more vulnerable—yet doubles the points earned for the enclosed area. Drawing begins when the player ventures into the open playfield from a boundary point, trailing a line that solidifies upon enclosure completion, turning the captured space solid and deducting it from the Qix's domain. A visible percentage counter tracks progress toward the level goal, and completing a level under time pressure awards a 1,000-point bonus, incentivizing efficient play.[15][2] The game's pacing is governed by a red timing line at the screen's top, which shrinks by one dot from each end every second; upon the ends meeting (typically after 37 seconds), it releases additional "Sparx" defenses that patrol boundaries, escalating threats mid-level. Prolonged idling in open space—defined as hesitation without drawing—triggers a lit fuse that races along the trail toward the marker, forcing constant motion and punishing indecision. Scoring primarily derives from the enclosed area's size (100 points per percentage claimed), amplified by draw mode and level multipliers, with free markers awarded every 50,000 points to extend play. These elements combine to create a tension between bold territorial grabs and cautious navigation, core to the game's puzzle-action hybrid.[15][3]Enemies and hazards

In the game Qix, the primary antagonist is the titular Qix, a colorful, amorphous entity composed of shifting lines that moves erratically across the unclaimed portions of the playfield. It poses a constant threat by colliding with any incomplete Stix (the lines drawn by the player's marker), causing the player to lose a life and forcing a restart of the current drawing attempt.[16] Starting from level 3, certain levels feature two Qix; to complete these, the player must draw a line that splits the open playfield into two regions, each isolating one Qix, which ends the level without requiring 75% enclosure and awards a score multiplier (starting at 2x and increasing with successive splits) applied to future scoring.[3][17] Sparx serve as perimeter-patrolling enemies that travel continuously along the edges of completed areas and the outer boundary, initially appearing as a pair moving in opposite directions (one clockwise, one counterclockwise). Contact with a Sparx destroys the player's marker, resulting in a lost life, and these enemies cannot traverse unfinished Stix until the area is fully enclosed.[16] As gameplay progresses, additional Sparx are introduced when a depleting timer (represented by a red bar at the top of the screen) expires, increasing their number or speed to heighten difficulty; in advanced states, "Super Sparx" variants emerge, capable of pursuing the player even along partially drawn lines.[18] Fuses act as a hazard triggered by player inaction, appearing at the starting point of an unfinished Stix if the marker remains stationary for too long (typically a few seconds). This fiery entity then races along the drawn line toward the marker, burning it upon contact and costing a life, thereby enforcing continuous movement during area enclosure.[17] Fuses can be avoided by promptly completing the enclosure before they reach the player, but they add tension to strategic drawing decisions in open playfield sections.[18]Release

Arcade version

The arcade version of Qix was developed by Taito America Corporation and released in October 1981.[19] It marked one of the early titles from Taito's U.S. branch, designed as a novel puzzle-action game that departed from the era's dominant shooter genres.[20] The game was produced as a wide release, distributed primarily to North American arcades before being imported to Japan later that year.[2] Qix ran on custom Taito hardware featuring a Motorola 68A09E processor for main gameplay logic and a Texas Instruments TMS5200 integrated circuit for speech synthesis, delivering amplified mono audio output.[2] The game supported both upright and cocktail cabinet formats, with the upright being the standard model for most installations.[2] Controls consisted of a 4-way joystick for marker movement along the playfield edges and two buttons to toggle between slow and fast drawing speeds, enabling single-player sessions or alternating two-player modes.[2] Initial arcade deployment emphasized the game's vector-style graphics on raster displays, which simulated wireframe visuals to create the illusion of drawing on a digital canvas.[20] Taito manufactured the cabinets with durable wooden construction typical of early 1980s arcade machines, including a 19-inch color monitor, coin mechanisms for quarters, and side art depicting abstract geometric patterns.[2] The title's release coincided with a surge in innovative arcade titles, positioning Qix as a quick-to-learn yet challenging addition to operator lineups.[19]Ports and adaptations

Following its 1981 arcade debut, Qix was ported to numerous home consoles and computers, beginning with early 1980s releases that aimed to replicate the original's vector-style graphics and gameplay on limited hardware. The first home console adaptation appeared on the Atari 5200 in 1983, developed and published by Atari, Inc., which preserved the core mechanics of drawing lines to claim territory while introducing adjustable difficulty levels for accessibility.[21] Similarly, a port for Atari 8-bit computers launched the same year, published by Atari, Inc., though it diverged slightly from the arcade by emphasizing distinct control schemes to suit keyboard and joystick inputs.[21] By the late 1980s, Qix expanded to 8-bit and 16-bit systems, with ports handled primarily by Taito Corporation and third-party developers. The Commodore 64 version, released in 1989 and published by Taito, featured smooth scrolling and audio effects closely mirroring the arcade, while the Apple II port from the same year, developed by Alien Technology Group, adapted the game's abstract visuals to raster graphics with minimal loss in strategic depth.[21] The Amiga adaptation in 1989, also by Alien Technology Group for Taito, stood out for its flawless execution, including enhanced color palettes and sound that elevated the original's minimalist design.[21] A Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) port followed in 1991, developed by Novotrade Software and published by Taito America Corporation, which maintained the tension of evading the Qix entity but simplified some enemy behaviors for the cartridge format.[21] Handheld adaptations brought Qix to portable play, notably the 1990 Game Boy version developed by Minakuchi Engineering and published by Nintendo, which incorporated cameo appearances by Mario and Luigi in intermission screens for added whimsy, alongside crisp monochrome graphics suited to the system's capabilities.[21] The Atari Lynx port in 1991, developed by Knight Technologies and published by Telegames, Inc., proved faithful to the arcade, retaining all features like slow-motion drawing modes while leveraging the handheld's color display for vibrant enemy trails.[21] A notable evolution came with Qix Adventure in 1999 for Game Boy Color, developed and published by Taito Corporation (with European release by Event Horizon Software), introducing an "Adventure" mode where players navigated a map-based overworld between standard Qix levels, expanding the puzzle format into light RPG elements.[22] Mobile and digital re-releases extended Qix's reach into the 2000s and beyond. Early mobile ports included Java ME (J2ME) in 2003, distributed by Taito Corporation via Orange France SA, and DoJa for Japanese feature phones in 2008, both optimizing touch-friendly controls for quick sessions.[21] Modern compilations revived the classic through emulation: the Game Boy version appeared on Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console in 2011 via Nintendo, while the arcade original joined Hamster Corporation's Arcade Archives series in 2022 for Nintendo Switch and PlayStation 4, adding features like online leaderboards and customizable screen orientations to appeal to contemporary audiences.[21] These ports and adaptations underscore Qix's enduring adaptability across hardware generations, from vector arcades to digital storefronts.Reception

Commercial performance

Upon its release in 1981, Qix proved to be an immediate commercial hit for Taito, performing strongly in arcade locations and generating substantial earnings, particularly among logic-oriented players on college campuses and in bars where it appealed to older demographics.[23] The game's innovative puzzle mechanics contributed to its rapid adoption, establishing it as one of the year's standout arcade titles in the United States.[24] In Japan, Qix ranked as the fifth highest-grossing arcade game of 1981, reflecting its broad appeal during the golden age of arcades.[24] It also saw notable success in Europe, where its abstract design and challenging gameplay resonated with players seeking alternatives to action-heavy titles.[4] Overall, the arcade version's profitability highlighted Taito's effective entry into the puzzle genre, though its minimalist visuals and high difficulty limited broader casual adoption. Despite this early success, Qix's popularity waned quickly, leading many operators to convert cabinets to higher-earning Taito games within a year, marking it as a modest rather than enduring commercial phenomenon.[23] Home ports fared worse; versions for the Nintendo Entertainment System and Game Boy in the late 1980s and early 1990s achieved only limited sales, failing to capture the arcade's quarter-dropping allure.[23] Later re-releases, such as Twin Qix in 1995, struggled amid market saturation by similar puzzle games like Tetris variants.[23]Critical response

Upon its release, Qix was praised by critics for its innovative blend of strategy and action in an abstract puzzle format. In the May 1982 issue of Electronic Games, columnist Bill Kunkel highlighted the game's originality in the Arcade Alley section, stating that "nothing else in the arcades is quite like it, in concept, play or audio-visual effects" and describing it as an "entertaining contest that should make for a pleasant—and highly challenging—change of pace from mazes and pure-action games."[25] Retrospective reviews have often echoed this appreciation for Qix's unique mechanics while noting its steep difficulty curve. GameSpot's 2004 analysis awarded it a 7.1 out of 10, commending the simplicity of its core concept—drawing lines to claim territory while evading hazards—but critiquing the frustration induced by unpredictable enemy movements and escalating challenges.[26] Similarly, a 2018 overview by Video Chums emphasized how the game's 1981 debut "initially delighted gamers" with its novel approach to territorial control, though it acknowledged the tension between risk and reward as a double-edged sword.[6]Accolades

Qix earned recognition at the 5th annual Arkie Awards, presented by Electronic Games magazine in its January 1984 issue, where it received a Certificate of Merit in the category of "Best Videogame Audio-Visual Effects (16K or more ROM)." This accolade highlighted the game's innovative vector graphics and dynamic visual presentation in its home computer and console ports, such as the Atari 5200 version released in 1983.[27]Legacy

Sequels and remakes

Following the original 1981 arcade release, Taito America produced Qix II: Tournament in 1982 as a direct sequel for arcades, enhancing the core mechanics with tournament-style scoring and minor graphical updates while retaining the line-drawing puzzle gameplay.[28][29] In 1987, Taito released Super Qix for arcades, introducing sprite-based enemies, power-ups, and collectible letters that formed words for bonuses, marking a significant evolution in visual and strategic depth compared to the original.[30][31] Volfied, launched by Taito in 1989 for arcades (titled Ultimate Qix in North America), served as a spiritual successor, expanding the formula with a sci-fi theme, ship-based drawing mechanics, and defensive weapons to combat enemies while claiming screen territory.[32][33] Taito's Twin Qix was a planned 1995 arcade sequel that reached prototype stage but was cancelled before release, featuring dual-screen play and cooperative elements.[34] Later entries include Qix Adventure, a 1999 Game Boy Color title by Taito that integrated role-playing elements with the classic Qix mechanics, allowing players to navigate levels and battle using area-claiming abilities.[22][35] Remakes began with Battle Qix in 2002, a Japan-exclusive PlayStation budget title by Success that reimagined the original as a versus-style multiplayer game with simplified controls for home consoles.[36] Taito revived the series in 2009 with Qix++, a downloadable remake for PlayStation Portable and Xbox Live Arcade that added modern features like online leaderboards, new modes, and enhanced visuals while preserving the addictive line-drawing core. More recently, Hamster Corporation, under Taito's license, included faithful emulations of Qix and its sequels in the Arcade Archives series, with the original Qix ported to platforms like Nintendo Switch and PlayStation 4 in 2022, offering adjustable difficulty and high-score tracking for contemporary audiences.[20]Clones and cultural impact

Qix's unique mechanics of territorial enclosure and abstract vector graphics inspired a proliferation of clones across arcade, PC, and home console platforms, particularly during the 1980s and 1990s. These derivatives often retained the core loop of drawing lines to claim screen areas while evading hazards, but varied in presentation and added elements like power-ups or themed visuals. Representative examples include Styx (1984), developed by Windmill Software for the Atari 8-bit family, which simplified the enclosure process with brush-like drawing tools; Xonix (1984), a PC clone emphasizing faster-paced area capture; and Antix (1985), another early PC adaptation that introduced color-based scoring variations.[37] A significant subset of clones adapted Qix's formula for adult entertainment, revealing partial images of scantily clad figures upon completing levels, which influenced niche genres in Japanese and Western markets. The Gals Panic series, starting in 1993 by Kaneko, exemplifies this trend by overlaying erotic imagery on the enclosure gameplay, spawning multiple sequels and imitators such as Perestroika Girls, Fantasia, and Fantasy '95. These titles demonstrated Qix's versatility as a foundational mechanic for reward-based progression systems.[38] Beyond direct clones, Qix's emphasis on strategic area control and minimalist design contributed to the emergence of the "area-filling contest" genre in puzzle gaming. It paved the way for titles like JezzBall (1992) by Microsoft, which inverted the mechanics to shrink hazardous areas on a grid, and influenced modern hybrids such as Poison Control (2021), blending enclosure puzzles with third-person shooting. This legacy underscores Qix's role in shifting arcade design toward cerebral, non-narrative challenges.[4] Culturally, Qix achieved widespread popularity as one of the top-earning arcade cabinets in the early 1980s, captivating players with its hypnotic visuals and tension-building gameplay despite lacking traditional characters or stories. Its abstract nature set it apart from contemporaneous hits like Pac-Man, fostering a cult following that persisted through ports and re-releases. The game's mechanics have echoed in broader media, including a Qix-inspired mini-game in Rockstar's Bully (2006), highlighting its enduring influence on interactive entertainment.[39]References

- https://strategywiki.org/wiki/Qix/Gameplay