Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Queue (abstract data type)

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2014) |

| Queue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

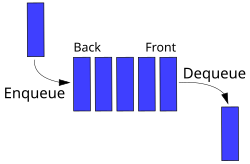

Representation of a FIFO (first in, first out) queue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

In computer science, a queue is an abstract data type that serves as a ordered collection of entities. By convention, the end of the queue where elements are added, is called the back, tail, or rear of the queue. The end of the queue where elements are removed is called the head or front of the queue. The name queue is an analogy to the words used to describe people in line to wait for goods or services. It supports two main operations.

- Enqueue, which adds one element to the rear of the queue

- Dequeue, which removes one element from the front of the queue.

Other operations may also be allowed, often including a peek or front operation that returns the value of the next element to be dequeued without dequeuing it.

The operations of a queue make it a first-in-first-out (FIFO) data structure as the first element added to the queue is the first one removed. This is equivalent to the requirement that once a new element is added, all elements that were added before have to be removed before the new element can be removed. A queue is an example of a linear data structure, or more abstractly a sequential collection. Queues are common in computer programs, where they are implemented as data structures coupled with access routines, as an abstract data structure or in object-oriented languages as classes. A queue may be implemented as circular buffers and linked lists, or by using both the stack pointer and the base pointer.

Queues provide services in computer science, transport, and operations research where various entities such as data, objects, persons, or events are stored and held to be processed later. In these contexts, the queue performs the function of a buffer. Another usage of queues is in the implementation of breadth-first search.

Queue implementation

[edit]Theoretically, one characteristic of a queue is that it does not have a specific capacity. Regardless of how many elements are already contained, a new element can always be added. It can also be empty, at which point removing an element will be impossible until a new element has been added again.

Fixed-length arrays are limited in capacity, but it is not true that items need to be copied towards the head of the queue. The simple trick of turning the array into a closed circle and letting the head and tail drift around endlessly in that circle makes it unnecessary to ever move items stored in the array. If n is the size of the array, then computing indices modulo n will turn the array into a circle. This is still the conceptually simplest way to construct a queue in a high-level language, but it does admittedly slow things down a little, because the array indices must be compared to zero and the array size, which is comparable to the time taken to check whether an array index is out of bounds, which some languages do, but this will certainly be the method of choice for a quick and dirty implementation, or for any high-level language that does not have pointer syntax. The array size must be declared ahead of time, but some implementations simply double the declared array size when overflow occurs. Most modern languages with objects or pointers can implement or come with libraries for dynamic lists. Such data structures may have not specified a fixed capacity limit besides memory constraints. Queue overflow results from trying to add an element onto a full queue and queue underflow happens when trying to remove an element from an empty queue.

A bounded queue is a queue limited to a fixed number of items.[1]

There are several efficient implementations of FIFO queues. An efficient implementation is one that can perform the operations—en-queuing and de-queuing—in O(1) time.

- Linked list

- A doubly linked list has O(1) insertion and deletion at both ends, so it is a natural choice for queues.

- A regular singly linked list only has efficient insertion and deletion at one end. However, a small modification—keeping a pointer to the last node in addition to the first one—will enable it to implement an efficient queue.

- A deque implemented using a modified dynamic array

Queues and programming languages

[edit]Queues may be implemented as a separate data type, or maybe considered a special case of a double-ended queue (deque) and not implemented separately. For example, Perl and Ruby allow pushing and popping an array from both ends, so one can use push and shift functions to enqueue and dequeue a list (or, in reverse, one can use unshift and pop),[2] although in some cases these operations are not efficient.

C++'s Standard Template Library provides a "queue" templated class which is restricted to only push/pop operations. Since J2SE5.0, Java's library contains a Queue interface that specifies queue operations; implementing classes include LinkedList and (since J2SE 1.6) ArrayDeque. PHP has an SplQueue class and third-party libraries like beanstalk'd and Gearman.

Example

[edit]A simple queue implemented in JavaScript:

class Queue {

constructor() {

this.items = [];

}

enqueue(element) {

this.items.push(element);

}

dequeue() {

return this.items.shift();

}

}

Purely functional implementation

[edit]Queues can also be implemented as a purely functional data structure.[3] There are two implementations. The first one only achieves per operation on average. That is, the amortized time is , but individual operations can take where n is the number of elements in the queue. The second implementation is called a real-time queue[4] and it allows the queue to be persistent with operations in O(1) worst-case time. It is a more complex implementation and requires lazy lists with memoization.

Amortized queue

[edit]This queue's data is stored in two singly-linked lists named and . The list holds the front part of the queue. The list holds the remaining elements (a.k.a., the rear of the queue) in reverse order. It is easy to insert into the front of the queue by adding a node at the head of . And, if is not empty, it is easy to remove from the end of the queue by removing the node at the head of . When is empty, the list is reversed and assigned to and then the head of is removed.

The insert ("enqueue") always takes time. The removal ("dequeue") takes when the list is not empty. When is empty, the reverse takes where is the number of elements in . But, we can say it is amortized time, because every element in had to be inserted and we can assign a constant cost for each element in the reverse to when it was inserted.

Real-time queue

[edit]The real-time queue achieves time for all operations, without amortization. This discussion will be technical, so recall that, for a list, denotes its length, that NIL represents an empty list and represents the list whose head is h and whose tail is t.

The data structure used to implement our queues consists of three singly-linked lists where f is the front of the queue and r is the rear of the queue in reverse order. The invariant of the structure is that s is the rear of f without its first elements, that is . The tail of the queue is then almost and inserting an element x to is almost . It is said almost, because in both of those results, . An auxiliary function must then be called for the invariant to be satisfied. Two cases must be considered, depending on whether is the empty list, in which case , or not. The formal definition is and where is f followed by r reversed.

Let us call the function which returns f followed by r reversed. Let us furthermore assume that , since it is the case when this function is called. More precisely, we define a lazy function which takes as input three lists such that , and return the concatenation of f, of r reversed and of a. Then . The inductive definition of rotate is and . Its running time is , but, since lazy evaluation is used, the computation is delayed until the results are forced by the computation.

The list s in the data structure has two purposes. This list serves as a counter for , indeed, if and only if s is the empty list. This counter allows us to ensure that the rear is never longer than the front list. Furthermore, using s, which is a tail of f, forces the computation of a part of the (lazy) list f during each tail and insert operation. Therefore, when , the list f is totally forced. If it was not the case, the internal representation of f could be some append of append of... of append, and forcing would not be a constant time operation anymore.

See also

[edit]- Event loop - events are stored in a queue

- Message queue

- Priority queue

- Queuing theory

- Stack (abstract data type) – the "opposite" of a queue: LIFO (Last In First Out)

References

[edit]- ^ "Queue (Java Platform SE 7)". Docs.oracle.com. 2014-03-26. Retrieved 2014-05-22.

- ^ "Class Array".

- ^ Okasaki, Chris. "Purely Functional Data Structures" (PDF).

- ^ Hood, Robert; Melville, Robert (November 1981). "Real-time queue operations in pure Lisp". Information Processing Letters. 13 (2): 50–54. doi:10.1016/0020-0190(81)90030-2. hdl:1813/6273.

General references

[edit] This article incorporates public domain material from Paul E. Black. "Bounded queue". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. NIST.

This article incorporates public domain material from Paul E. Black. "Bounded queue". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. NIST.

Further reading

[edit]- Donald Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89683-4. Section 2.2.1: Stacks, Queues, and Dequeues, pp. 238–243.

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Section 10.1: Stacks and queues, pp. 200–204.

- William Ford, William Topp. Data Structures with C++ and STL, Second Edition. Prentice Hall, 2002. ISBN 0-13-085850-1. Chapter 8: Queues and Priority Queues, pp. 386–390.

- Adam Drozdek. Data Structures and Algorithms in C++, Third Edition. Thomson Course Technology, 2005. ISBN 0-534--0

{{isbn}}: Checkisbnvalue: length (help). Chapter 4: Stacks and Queues, pp. 137–169.

External links

[edit]Queue (abstract data type)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

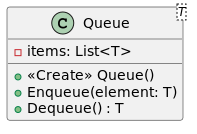

A queue is an abstract data type that models a linear collection of elements organized according to the First-In-First-Out (FIFO) principle, meaning the first element added to the queue is the first one removed, with insertions occurring at the rear (or tail) and deletions at the front (or head).[4] This structure ensures that elements maintain their relative order of arrival without permitting intermediate access or reordering.[5] Key characteristics of a queue include its ordered nature, where elements form a sequence processed strictly in insertion order, and restricted access that prohibits indexing or random retrieval, focusing solely on endpoint operations.[6] This mirrors real-world scenarios such as a checkout line at a store, where customers join at the end and leave from the front, preventing cutting in line to preserve fairness and sequence.[7] The concept of queues emerged in early computing during the 1950s, particularly in batch processing systems where jobs—submitted via punched cards—were organized into queues for sequential execution by operators on mainframe computers, optimizing limited machine time.[8] It was later formalized within data structure theory in Donald Knuth's "The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms," first published in 1968, which systematically analyzed queues alongside related structures.[9] In contrast to stacks, which adhere to Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) and remove the most recently added element, queues uniquely enforce FIFO to process elements in arrival order; unlike linked lists or arrays that support random access via indices, queues limit operations to the extremities, emphasizing sequential discipline.[1] Basic operations on a queue, such as enqueue and dequeue, align with these endpoint restrictions.[2]Basic Operations

The basic operations of the queue abstract data type (ADT) provide the essential interface for managing elements in a first-in, first-out (FIFO) manner, allowing controlled insertion and removal while handling state-based errors such as underflow (attempting to remove from an empty queue) and overflow (attempting to insert into a full queue). These operations abstract away implementation details, focusing on behavioral semantics that ensure the oldest element is always processed first.[1][10] The enqueue operation (also known as push or add) inserts a new element at the rear (end) of the queue, extending the structure while preserving the order of existing elements. It typically returns void but may throw an exception or return a status indicator if the queue is full, preventing overflow in bounded implementations. Pseudocode for enqueue:function enqueue(element):

if isFull():

raise OverflowError // or handle as per policy

add element to rear

increment size

function enqueue(element):

if isFull():

raise OverflowError // or handle as per policy

add element to rear

increment size

function dequeue():

if isEmpty():

raise UnderflowError // or handle as per policy

element = remove from front

decrement size

return element

function dequeue():

if isEmpty():

raise UnderflowError // or handle as per policy

element = remove from front

decrement size

return element

function peek():

if isEmpty():

raise UnderflowError // or handle as per policy

return element at front

function peek():

if isEmpty():

raise UnderflowError // or handle as per policy

return element at front

function isEmpty():

return size == 0

function isEmpty():

return size == 0

function isFull():

return size == maximum_capacity

function isFull():

return size == maximum_capacity

function size():

return current_count_of_elements

function size():

return current_count_of_elements

Analysis

Time and Space Complexity

The time complexity of core queue operations, such as enqueue, dequeue, and peek, is O(1) on average in efficient implementations that avoid linear-time shifts or reallocations.[11] In contrast, naive implementations using a linear array without buffering can incur O(n time for dequeue, as removing the front element requires shifting all subsequent elements to fill the gap.[14] The Big O notation here captures the worst-case growth rate relative to the number of elements n; for instance, enqueue in a linked list implementation achieves O(1) time by appending a new node to the rear pointer without traversing the structure, whereas in a non-circular array, repeated enqueues after dequeues may lead to O(n shifts if the front is not managed efficiently.[7] Space complexity for a queue is O(n), where n represents the number of stored elements, as the structure must allocate memory proportional to the queue's size.[7] This includes auxiliary space of O(1) for metadata, such as pointers to the front and rear positions, which remain constant regardless of n.[7] Factors like resizing in dynamic array-based queues can temporarily elevate enqueue time to O(n) during capacity expansion, but the amortized cost over a sequence of operations remains O(1) due to infrequent resizes relative to the total insertions.[11]Performance Considerations

In modern computer architectures, cache locality significantly impacts the performance of queue implementations. Array-based queues benefit from sequential memory access patterns, which align well with cache line prefetching and reduce cache misses during enqueue and dequeue operations. In contrast, linked list-based queues often suffer from poor cache locality due to scattered memory allocations for nodes, leading to frequent pointer chasing and higher cache miss rates that can degrade throughput by factors of 2 to 10 in high-access workloads.[15][16] Thread safety is a critical performance factor in multi-threaded environments, particularly in producer-consumer scenarios where multiple threads concurrently access the queue. Traditional locking mechanisms, such as mutexes, ensure correctness but introduce overhead from contention and context switches, potentially reducing scalability on multi-core systems. Lock-free alternatives, like the Michael-Scott queue algorithm, use atomic operations to achieve progress without locks, which can offer higher throughput than locked implementations in many scenarios, though performance depends on workload and hardware, with locked queues sometimes scaling better under extreme contention.[17][18] Dynamic queues implemented with arrays require resizing to handle varying loads, typically employing a doubling strategy for capacity growth and halving for shrinkage to achieve amortized O(1) time per operation. This approach spreads the O(n) cost of copying elements across multiple insertions, ensuring that the total time for n operations remains O(n), but individual resizes can cause temporary latency spikes in real-time systems.[19] Empirical benchmarks highlight these factors in high-throughput applications, such as message passing in operating system kernels. Array-based queue implementations with careful padding for cache alignment can achieve low latencies, such as under 1 μs per operation in single-threaded scenarios on modern hardware, while linked list variants often exhibit higher latency due to cache inefficiencies under multi-core loads. In producer-consumer tests on multi-core systems, lock-free queues like the batched BQ variant can significantly outperform traditional locked implementations under contention.[18][20] Performance trade-offs often arise between predictability and flexibility, especially in resource-constrained environments like embedded systems. Fixed-size queues provide deterministic O(1) operations without allocation overhead, ideal for real-time applications where worst-case latency must remain below 10 μs, but they risk overflows in variable workloads. Dynamic queues offer adaptability for fluctuating demands, yet their resizing and potential fragmentation can increase memory footprint and introduce non-determinism unsuitable for safety-critical embedded contexts.[21]Traditional Implementations

Array-Based Queue

An array-based queue utilizes a contiguous block of memory to store elements, typically maintaining two indices:front, pointing to the first element, and rear, indicating the position after the last element. In a basic fixed-size implementation, the array is allocated with a capacity of to distinguish between full and empty states, where is the maximum number of elements. Enqueue operations add elements at the rear index and increment rear, while dequeue operations remove elements from the front index and increment front. This setup allows for efficient access but requires careful management to avoid overwriting data.

A naive array-based queue without optimizations suffers from inefficiency during dequeues, as removing the front element necessitates shifting all subsequent elements forward to maintain contiguity, resulting in O(n) time complexity for each dequeue. To mitigate this, a circular array implementation wraps indices around the array bounds using modulo arithmetic, such as (rear + 1) % capacity for enqueue and (front + 1) % capacity for dequeue, enabling O(1) operations without shifting. This approach briefly introduces the circular buffering technique, which optimizes space usage by reusing the space ahead of the front pointer as the rear advances.

For unbounded growth, dynamic resizing extends the fixed-size model by doubling the array capacity when full: a new larger array is allocated, elements are copied from the old array, and the old array is deallocated. This amortized approach ensures enqueue remains efficient over sequences of operations, though individual resizes incur O(n) cost. In pseudocode, this might appear as:

if (size == capacity) {

newCapacity = capacity * 2;

newArray = allocate(newCapacity);

copy elements from oldArray to newArray, adjusting for circular positions;

free(oldArray);

capacity = newCapacity;

}

rear = (rear + 1) % capacity;

array[rear] = element;

size++;

if (size == capacity) {

newCapacity = capacity * 2;

newArray = allocate(newCapacity);

copy elements from oldArray to newArray, adjusting for circular positions;

free(oldArray);

capacity = newCapacity;

}

rear = (rear + 1) % capacity;

array[rear] = element;

size++;

Linked List-Based Queue

A linked list-based queue utilizes a singly linked list where each node contains data and a pointer to the next node, with two external pointers maintained:front pointing to the head (first element) and rear pointing to the tail (last element).[22] This structure allows dynamic growth without predefined size limits, as nodes are allocated on demand.[23] To handle the empty state, both front and rear are set to null initially, and operations check for this condition to avoid invalid accesses.[22] Unlike fixed-size implementations, there is no inherent "full" state, as the list can expand indefinitely subject to available memory.[23]

The enqueue operation adds a new element to the rear in constant time by creating a new node, setting its data, and linking it to the current rear node's next pointer, then updating rear to point to the new node.[22] If the queue is empty, both front and rear are updated to the new node.[23] This avoids the need for shifting elements, ensuring O(1) amortized time.[22]

Dequeue removes and returns the element at the front by updating front to point to the next node and freeing the memory of the removed node.[22] If the queue becomes empty after removal, rear is also set to null.[23] This operation is also O(1), as it only involves pointer adjustments at the head.[22]

This implementation offers advantages such as unbounded size and no element shifting during insertions or deletions, making it suitable for scenarios with unpredictable queue lengths.[23] However, it incurs higher memory overhead per element due to the storage of next pointers and exhibits poorer cache locality compared to contiguous structures, as nodes may be scattered in memory.[22] Space complexity is O(n) where n is the number of elements, plus additional overhead for pointers.[22]

The following pseudocode illustrates a basic node class and key operations in a language-agnostic style:

class Node {

data

next

}

class LinkedQueue {

front = null

rear = null

enqueue(element) {

newNode = new Node()

newNode.data = element

newNode.next = null

if (front == null) {

front = rear = newNode

} else {

rear.next = newNode

rear = newNode

}

}

dequeue() {

if (front == null) {

return null // or throw error

}

temp = front.data

front = front.next

if (front == null) {

rear = null

}

return temp

}

}

class Node {

data

next

}

class LinkedQueue {

front = null

rear = null

enqueue(element) {

newNode = new Node()

newNode.data = element

newNode.next = null

if (front == null) {

front = rear = newNode

} else {

rear.next = newNode

rear = newNode

}

}

dequeue() {

if (front == null) {

return null // or throw error

}

temp = front.data

front = front.next

if (front == null) {

rear = null

}

return temp

}

}

Language Integration

Support in Programming Languages

In object-oriented languages like Java, the Queue interface is provided in the java.util package as part of the Collections Framework, defining core operations such as offer, poll, and peek for FIFO behavior.[24] Implementations include LinkedList, which uses a doubly-linked list for O(1) insertions and deletions at both ends, and ArrayDeque, an efficient array-based alternative without fixed capacity limits.[25] This interface enables polymorphic usage, allowing queues to be substituted with compatible collections while maintaining type safety. Python offers robust queue support through the collections module, where deque serves as a double-ended queue optimized for append and pop operations from either end with O(1) average time complexity.[26] For concurrent programming, the queue module provides thread-safe Queue and PriorityQueue classes, built on locks to handle producer-consumer scenarios without race conditions.[27] These structures integrate seamlessly with Python's iterable protocols, facilitating easy conversion to lists or other sequences. In C++, the standard library includes std::queue as a container adaptor in thePseudocode Example

To illustrate the abstract data type (ADT) for a queue, the following pseudocode defines a generic queue structure using an underlying array of fixed capacity , with indices for the front and rear pointers, and a size counter to track the number of elements. This representation maintains the FIFO (first-in, first-out) order while allowing adaptation to linked structures by replacing array operations with pointer manipulations. The operations include enqueue (add to rear), dequeue (remove from front), peek (view front without removal), isEmpty, isFull, and size, with exceptions thrown for underflow (dequeue or peek on empty queue) and overflow (enqueue on full queue).[23]Class Queue:

// Fields

items: array of capacity N // Generic elements, e.g., integers

front: integer = 0 // Index of front element

rear: integer = 0 // Index after rear element (circular)

size: integer = 0 // Number of elements

N: integer // Fixed capacity

Method createQueue(capacity):

N = capacity

items = new [array](/page/Array)[N]

front = 0

rear = 0

size = 0

Method isEmpty():

return size == 0

Method isFull():

return size == N

Method enqueue(newItem):

if isFull():

throw QueueOverflowException("Queue is full")

items[rear] = newItem

rear = (rear + 1) mod N

size = size + 1

Method dequeue():

if isEmpty():

throw QueueUnderflowException("Queue is empty")

temp = items[front]

items[front] = null // Optional for garbage collection

front = (front + 1) mod N

size = size - 1

return temp

Method peek():

if isEmpty():

throw QueueUnderflowException("Queue is empty")

return items[front]

Method getSize():

return size

Class Queue:

// Fields

items: array of capacity N // Generic elements, e.g., integers

front: integer = 0 // Index of front element

rear: integer = 0 // Index after rear element (circular)

size: integer = 0 // Number of elements

N: integer // Fixed capacity

Method createQueue(capacity):

N = capacity

items = new [array](/page/Array)[N]

front = 0

rear = 0

size = 0

Method isEmpty():

return size == 0

Method isFull():

return size == N

Method enqueue(newItem):

if isFull():

throw QueueOverflowException("Queue is full")

items[rear] = newItem

rear = (rear + 1) mod N

size = size + 1

Method dequeue():

if isEmpty():

throw QueueUnderflowException("Queue is empty")

temp = items[front]

items[front] = null // Optional for garbage collection

front = (front + 1) mod N

size = size - 1

return temp

Method peek():

if isEmpty():

throw QueueUnderflowException("Queue is empty")

return items[front]

Method getSize():

return size

| Operation | Action | Queue Contents | Front | Rear | Size | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| createQueue(4) | Initialize | [] | 0 | 0 | 0 | Empty queue created. |

| enqueue(1) | Add 1 to rear | [33] | 0 | 1 | 1 | Successful. |

| enqueue(2) | Add 2 to rear | [1, 2] | 0 | 2 | 2 | Successful. |

| enqueue(3) | Add 3 to rear | [1, 2, 3] | 0 | 3 | 3 | Successful. |

| dequeue() | Remove from front | [2, 3] | 1 | 3 | 2 | Returns 1; no exception. |

| peek() | View front | [2, 3] | 1 | 3 | 2 | Returns 2; no exception. |

| isEmpty() | Check empty | [2, 3] | 1 | 3 | 2 | Returns false. |

| enqueue(4) | Add 4 to rear | [2, 3, 4] | 1 | 0 | 3 | Successful (wraps around). |

| enqueue(5) | Add 5 to rear | [2, 3, 4, 5] | 1 | 1 | 4 | Successful. |

| enqueue(6) | Add 6 to rear | N/A | 1 | 1 | 4 | Throws QueueOverflowException("Queue is full"). |

Functional Implementations

Amortized Functional Queue

In purely functional programming paradigms, queues are implemented using immutable data structures, where each operation produces a new version of the queue without modifying the existing one. This persistence enables thread-safety and allows multiple consumers to operate on different versions simultaneously, as updates create shared substructures through techniques like structural sharing in cons cells. The amortized functional queue, as developed by Chris Okasaki, achieves efficient first-in, first-out (FIFO) behavior by representing the queue as two lists: a front list holding elements in order for dequeuing and a rear list holding elements in reverse order for enqueuing.[34] Enqueue appends a new element to the rear list in constant time using cons, while dequeue removes and returns the head of the front list, also in constant time if the front is non-empty. When the front list empties during dequeue, a rotation occurs: the rear list is reversed and becomes the new front, with the rear reset to empty. This rotation takes linear time in the size of the rear list, but it is infrequent, occurring only after a sequence of enqueues that deplete the front. To ensure balance, implementations often track list lengths explicitly, triggering rotation when the rear exceeds the front in size.[34] Amortization is analyzed using the potential method, where the potential function is defined as the length of the rear list, capturing the "banked" cost for future rotations. Each enqueue incurs an actual cost of 1 (for cons) and increases the potential by 1, yielding an amortized cost of 2; each dequeue from a non-empty front has actual cost 1 and no change in potential (amortized cost 1); and during rotation on dequeue, the actual cost of O(n) (where n = |rear|) is offset by a potential drop of n, resulting in amortized cost 1. Over a sequence of operations, this confirms O(1) amortized time per operation.[34] The following Haskell-like pseudocode illustrates the structure and operations, assuming lists with cons (:), head (head), tail (tail), reverse (reverse), and empty ([]):

data Queue a = Q [a] [a] -- front, rear (reversed)

empty :: Queue a

empty = Q [] []

enqueue :: a -> Queue a -> Queue a

enqueue x (Q f r) = Q f (x : r)

dequeue :: Queue a -> Maybe (a, Queue a)

dequeue (Q [] r)

| null r = Nothing

| otherwise = let f' = reverse r in dequeue (Q f' [])

dequeue (Q (x:f) r) = Just (x, Q f r)

headQ :: Queue a -> Maybe a

headQ (Q [] _) = Nothing

headQ (Q (x:_) _) = Just x

data Queue a = Q [a] [a] -- front, rear (reversed)

empty :: Queue a

empty = Q [] []

enqueue :: a -> Queue a -> Queue a

enqueue x (Q f r) = Q f (x : r)

dequeue :: Queue a -> Maybe (a, Queue a)

dequeue (Q [] r)

| null r = Nothing

| otherwise = let f' = reverse r in dequeue (Q f' [])

dequeue (Q (x:f) r) = Just (x, Q f r)

headQ :: Queue a -> Maybe a

headQ (Q [] _) = Nothing

headQ (Q (x:_) _) = Just x

Real-Time Functional Queue

Real-time functional queues provide worst-case O(1) time complexity for both enqueue and dequeue operations, eliminating the amortization that can lead to unpredictable performance spikes in other functional implementations; this predictability is particularly valuable in embedded systems and real-time applications where timing guarantees are critical.[35][34] Hood and Melville's seminal design for real-time queues, implemented in pure LISP, leverages lazy evaluation and streams to achieve these guarantees without mutable state.[35] The queue structure consists of a front stream representing the accessible elements, a rear stream for incoming elements (stored in reverse order), and a schedule stream that ensures balanced rotation, maintaining the invariant to prevent drift.[34] Both front and rear are represented as suspensions—delayed computations that force evaluation only when needed—allowing incremental processing without immediate overhead.[35][34] Enqueue (often denoted as snoc) operates in O(1) time by creating a new rear stream: it conses the new element onto and suspends the result, updating the schedule accordingly without forcing any computations.[34] Dequeue advances the front stream in O(1) time by forcing the head of and tailing it, while decrementing the schedule; if , a rotation is triggered incrementally via the schedule stream, which lazily reverses and appends to one element at a time across multiple operations, ensuring no single step exceeds constant time.[35][34] This scheduling mechanism distributes the O(n) rotation cost over 2n operations, but the laziness and confluence properties of the language guarantee that forces do not cascade, yielding strict O(1) worst-case performance.[34] The mathematical guarantees stem from the semantics of lazy evaluation in functional languages, where suspensions have an intrinsic O(1) cost and the schedule enforces confluence—ensuring that the order of evaluation does not affect the final structure or introduce hidden allocations.[35][34] For instance, in a Haskell-like pseudocode representation:data Queue a = Q (Susp (Stream a)) (Stream a) (Susp (Stream ()))

snoc (Q f r s) x = Q f (x : r) (suspend (step s (rot f (reverse r))))

tail (Q (_ :> f') r s) = Q f' r (suspend (step s (rot f' (reverse r))))

data Queue a = Q (Susp (Stream a)) (Stream a) (Susp (Stream ()))

snoc (Q f r s) x = Q f (x : r) (suspend (step s (rot f (reverse r))))

tail (Q (_ :> f') r s) = Q f' r (suspend (step s (rot f' (reverse r))))

rot lazily computes the rotation, and step advances the schedule by one unit, with suspend delaying the stream construction.[34] Unlike amortized functional queues, which may incur occasional O(n) operations during rebuilding (e.g., full reversals), Hood-Melville queues avoid such spikes entirely, providing fully predictable behavior suitable for hard real-time constraints.[34][36]

Despite these strengths, real-time functional queues exhibit limitations in implementation complexity, as managing suspensions and schedules requires careful handling of laziness to avoid space leaks from unevaluated thunks.[34] They also rely heavily on the host language's garbage collection and lazy evaluation support, which may introduce latency in non-optimizing environments or strict languages without extensions.[35][34]

Variants and Extensions

Circular Buffer Queue

A circular buffer queue, also known as a ring buffer, implements the queue abstract data type using a fixed-size array where indices wrap around using modular arithmetic, allowing efficient reuse of space without shifting elements.[37] This approach maintains two key indices: the front (pointing to the first element) and the rear (pointing to the next insertion position). When the rear reaches the end of the array, it cycles back to the beginning via the formularear = (rear + 1) % size, where size is the array capacity, ensuring continuous operation in a circular manner.[38]

To distinguish between an empty queue and a full one—both of which can result in front == rear—implementations typically reserve one slot unused or maintain a separate count variable. With the reserved slot method, the queue is full when (rear + 1) % [size](/page/Size) == front, allowing up to size - 1 elements; the count method tracks the number of elements explicitly for exact capacity use.[37] Enqueue adds an element at the rear index and advances the rear (rear = (rear + 1) % [size](/page/Size)), while dequeue removes from the front and advances the front (front = (front + 1) % [size](/page/Size)); both operations, along with peek (accessing the front without removal), achieve O(1) time complexity without array shifting.[39]

This structure excels in applications requiring fixed-memory buffers, such as TCP send and receive windows in networking, where a circular buffer holds outgoing data until acknowledged, sliding the window forward upon receipt of ACKs to manage flow control efficiently.[40] In embedded systems, it supports real-time data processing with predictable performance and minimal overhead, ideal for resource-constrained environments like sensor logging or interrupt handling.[41]

Key advantages include constant-time operations, optimal space utilization up to nearly 100% capacity, and no need for dynamic resizing, making it suitable for systems with strict memory limits.[37] However, the fixed capacity necessitates overflow handling, such as blocking enqueues or discarding elements, and careful initialization to avoid misinterpreting states.[39]

The following pseudocode illustrates a basic implementation in a C-like syntax, using a reserved slot for full/empty detection:

[typedef](/page/Typedef) struct {

int* array;

int front;

int rear;

int capacity;

int count; // Optional for exact tracking, but here using [reserved](/page/Reserved) slot

} CircularQueue;

void init(CircularQueue* q, int size) {

q->array = malloc(size * sizeof(int));

q->front = 0;

q->rear = 0;

q->capacity = size;

q->count = 0;

}

bool isEmpty(CircularQueue* q) {

return q->front == q->rear;

}

bool isFull(CircularQueue* q) {

return (q->rear + 1) % q->capacity == q->front;

}

void enqueue(CircularQueue* q, int value) {

if (isFull(q)) {

// Handle overflow, e.g., return or block

return;

}

q->array[q->rear] = value;

q->rear = (q->rear + 1) % q->capacity;

q->count++;

}

int dequeue(CircularQueue* q) {

if (isEmpty(q)) {

// Handle underflow

return -1;

}

int value = q->array[q->front];

q->front = (q->front + 1) % q->capacity;

q->count--;

return value;

}

int peek(CircularQueue* q) {

if (isEmpty(q)) return -1;

return q->array[q->front];

}

[typedef](/page/Typedef) struct {

int* array;

int front;

int rear;

int capacity;

int count; // Optional for exact tracking, but here using [reserved](/page/Reserved) slot

} CircularQueue;

void init(CircularQueue* q, int size) {

q->array = malloc(size * sizeof(int));

q->front = 0;

q->rear = 0;

q->capacity = size;

q->count = 0;

}

bool isEmpty(CircularQueue* q) {

return q->front == q->rear;

}

bool isFull(CircularQueue* q) {

return (q->rear + 1) % q->capacity == q->front;

}

void enqueue(CircularQueue* q, int value) {

if (isFull(q)) {

// Handle overflow, e.g., return or block

return;

}

q->array[q->rear] = value;

q->rear = (q->rear + 1) % q->capacity;

q->count++;

}

int dequeue(CircularQueue* q) {

if (isEmpty(q)) {

// Handle underflow

return -1;

}

int value = q->array[q->front];

q->front = (q->front + 1) % q->capacity;

q->count--;

return value;

}

int peek(CircularQueue* q) {

if (isEmpty(q)) return -1;

return q->array[q->front];

}

Priority Queue

A priority queue is an abstract data type that maintains a collection of elements, each associated with a priority value, and supports operations to insert elements and remove the one with the highest (or lowest) priority, rather than strictly following first-in, first-out (FIFO) order.[42] Unlike a standard queue, where elements are dequeued based on insertion time, a priority queue dequeues based on the priority ordering, which can be ascending (min-priority queue) or descending (max-priority queue).[42] This structure is particularly useful when the processing order must reflect urgency or importance rather than arrival sequence.[43] Key operations include insertion of an element with its priority, extraction of the minimum or maximum priority element (remove-min or remove-max), and, in some variants, decreasing the key (or priority) of an existing element to reflect updated conditions.[42] These operations deviate from pure FIFO by allowing priority-based selection, enabling efficient management of dynamic priorities without full resorting.[44] For example, in an emergency room, patients are triaged by severity: a critically ill patient arriving later would be treated before others who arrived earlier but have lower severity.[45] Common implementations use heap data structures to achieve efficient performance. A binary heap provides O(log n) time for both insertion and extract-min/max operations, balancing simplicity and efficiency for most applications.[42] For superior amortized performance, the Fibonacci heap, introduced by Fredman and Tarjan, supports insertion and decrease-key in amortized O(1) time, with extract-min in amortized O(log n) time, making it ideal for algorithms with frequent updates.[46] Priority queues are foundational in graph algorithms and system management. In Dijkstra's shortest path algorithm, a priority queue selects the next vertex with the smallest tentative distance, enabling efficient computation of shortest paths in weighted graphs without negative edges.[47] In operating systems, they facilitate task scheduling by prioritizing processes based on urgency, ensuring high-priority tasks execute before lower ones to optimize resource allocation and responsiveness.[48]Double-Ended Queue (Deque)

A double-ended queue, or deque, is an abstract data type that extends the queue by permitting insertions and deletions at both the front and the rear ends, thereby generalizing both queues and stacks.[49] This bidirectional access enables flexible manipulation of sequences while maintaining linear ordering.[50] The primary operations of a deque include:addFirst(e)orpush_front(e): Insert elementeat the front.addLast(e)orpush_back(e): Insert elementeat the rear.removeFirst()orpop_front(): Remove and return the front element (or indicate empty).removeLast()orpop_back(): Remove and return the rear element (or indicate empty).first()orfront(): Access the front element without removal.last()orback(): Access the rear element without removal.isEmpty(): Check if the deque is empty.size(): Return the number of elements.

push_back) and deletions to the front (pop_front), enforcing first-in, first-out (FIFO) order.[49]

Deques find applications in scenarios requiring bidirectional access, such as undo/redo mechanisms in text editors and user interfaces, where actions are appended to one end and reversed by removing from the opposite end to support both forward and backward navigation.[51] They are also used in sliding window algorithms, like computing the maximum element in a fixed-size window over an array, by maintaining a deque of indices in decreasing order of values to efficiently track candidates as the window slides.[52] Additionally, deques facilitate palindrome checks on strings or sequences by pushing characters from both ends and comparing pairwise until the center.[53]

Example Sequence of OperationsConsider an initially empty deque:

push_back(10): Deque = [54]push_back(20): Deque = [10, 20]push_front(5): Deque = [5, 10, 20]pop_front(): Returns 5; Deque = [10, 20]push_front(15): Deque = [15, 10, 20]pop_back(): Returns 20; Deque = [15, 10]

References

- Feb 13, 2020 · A stack-ended queue or steque is a data type that supports push, pop, and enqueue. Knuth calls it an output-restricted deque.

- The Queue Abstract Data Type · Customers wait in a line to be served. · Customers leave the line at one end (the front), when they have been served by the clerk.