Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

FIFO (computing and electronics)

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

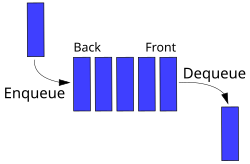

In computing and in systems theory, first in, first out (the first in is the first out), acronymized as FIFO, is a method for organizing the manipulation of a data structure (often, specifically a data buffer) where the oldest (first) entry, or "head" of the queue, is processed first.

Such processing is analogous to servicing people in a queue area on a first-come, first-served (FCFS) basis, i.e. in the same sequence in which they arrive at the queue's tail.

FCFS is also the jargon term for the FIFO operating system scheduling algorithm, which gives every process central processing unit (CPU) time in the order in which it is demanded.[1] FIFO's opposite is LIFO, last-in-first-out, where the youngest entry or "top of the stack" is processed first.[2] A priority queue is neither FIFO or LIFO but may adopt similar behaviour temporarily or by default. Queueing theory encompasses these methods for processing data structures, as well as interactions between strict-FIFO queues.

Computer science

[edit]

Depending on the application, a FIFO could be implemented as a hardware shift register, or using different memory structures, typically a circular buffer or a kind of list. For information on the abstract data structure, see Queue (data structure). Most software implementations of a FIFO queue are not thread safe and require a locking mechanism to verify the data structure chain is being manipulated by only one thread at a time.

The following code shows a linked list FIFO C++ language implementation. In practice, a number of list implementations exist, including popular Unix systems C sys/queue.h macros or the C++ standard library std::list template, avoiding the need for implementing the data structure from scratch.

#include <memory>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

template <typename T>

class FIFO {

struct Node {

T value;

shared_ptr<Node> next = nullptr;

Node(T _value): value(_value) {}

};

shared_ptr<Node> front = nullptr;

shared_ptr<Node> back = nullptr;

public:

void enqueue(T _value) {

if (front == nullptr) {

front = make_shared<Node>(_value);

back = front;

} else {

back->next = make_shared<Node>(_value);

back = back->next;

}

}

T dequeue() {

if (front == nullptr)

throw underflow_error("Nothing to dequeue");

T value = front->value;

front = move(front->next);

return value;

}

};

In computing environments that support the pipes-and-filters model for interprocess communication, a FIFO is another name for a named pipe.

Disk controllers can use the FIFO as a disk scheduling algorithm to determine the order in which to service disk I/O requests, where it is also known by the same FCFS initialism as for CPU scheduling mentioned before.[1]

Communication network bridges, switches and routers used in computer networks use FIFOs to hold data packets in route to their next destination. Typically at least one FIFO structure is used per network connection. Some devices feature multiple FIFOs for simultaneously and independently queuing different types of information.[3]

Electronics

[edit]

FIFOs are commonly used in electronic circuits for buffering and flow control between hardware and software. In its hardware form, a FIFO primarily consists of a set of read and write pointers, storage and control logic. Storage may be static random access memory (SRAM), flip-flops, latches or any other suitable form of storage. For FIFOs of non-trivial size, a dual-port SRAM is usually used, where one port is dedicated to writing and the other to reading.

The first known FIFO implemented in electronics was by Peter Alfke in 1969 at Fairchild Semiconductor.[4] Alfke was later a director at Xilinx.

Synchronicity

[edit]A synchronous FIFO is a FIFO where the same clock is used for both reading and writing. An asynchronous FIFO uses different clocks for reading and writing and they can introduce metastability issues. A common implementation of an asynchronous FIFO uses a Gray code (or any unit distance code) for the read and write pointers to ensure reliable flag generation. One further note concerning flag generation is that one must necessarily use pointer arithmetic to generate flags for asynchronous FIFO implementations. Conversely, one may use either a leaky bucket approach or pointer arithmetic to generate flags in synchronous FIFO implementations.

A hardware FIFO is used for synchronization purposes. It is often implemented as a circular queue, and thus has two pointers:

- Read pointer / read address register

- Write pointer / write address register

Status flags

[edit]Examples of FIFO status flags include: full, empty, almost full, and almost empty. A FIFO is empty when the read address register reaches the write address register. A FIFO is full when the write address register reaches the read address register. Read and write addresses are initially both at the first memory location and the FIFO queue is empty.

In both cases, the read and write addresses end up being equal. To distinguish between the two situations, a simple and robust solution is to add one extra bit for each read and write address which is inverted each time the address wraps. With this set up, the disambiguation conditions are:

- When the read address register equals the write address register, the FIFO is empty.

- When the read and write address registers differ only in the extra most significant bit and the rest are equal, the FIFO is full.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Andrew S. Tanenbaum; Herbert Bos (2015). Modern Operating Systems. Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-359162-0.

- ^ Kruse, Robert L. (1987) [1984]. Data Structures & Program Design (second edition). Joan L. Stone, Kenny Beck, Ed O'Dougherty (production process staff workers) (second (hc) textbook ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. div. of Simon & Schuster. p. 150. ISBN 0-13-195884-4.

- ^ James F. Kurose; Keith W. Ross (July 2006). Computer Networking: A Top-Down Approach. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-41849-4.

- ^ "Peter Alfke's post at comp.arch.fpga on 19 Jun 1998".

External links

[edit]FIFO (computing and electronics)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

In computing and electronics, FIFO, or First In, First Out, is a queuing method that organizes data elements such that the first element inserted into the queue is the first one to be removed, ensuring strict adherence to the order of arrival.[1] This principle maintains temporal sequence, distinguishing FIFO from other structures like stacks, which operate on a Last In, First Out (LIFO) basis, or priority queues, where removal order depends on assigned priorities rather than insertion time.[1] The FIFO discipline is fundamental for managing ordered data flows, preventing overtaking and preserving causality in both software algorithms and hardware buffers.[9] The core operations of a FIFO queue are enqueue, which adds an element to the rear (tail) of the queue, and dequeue, which removes and retrieves the element from the front (head).[1] Abstractly, these operations are supported by pointers or indices tracking the head and tail positions, allowing efficient access without shifting elements during insertions or deletions in conceptual models.[10] A typical FIFO can be visualized as a linear arrangement, akin to a single-file line: elements enter sequentially at one end (enqueue) and exit from the opposite end (dequeue), forming a buffer that grows or shrinks while maintaining order, with empty states when head meets tail and full states when capacity is reached.[9] The FIFO concept traces its roots to operations research in the early 20th century, notably through Agner Krarup Erlang's 1909 models for telephone call queuing, which formalized the analysis of arrival and service sequences.[11] In computing, the term and principle were applied to job scheduling in early electronic computers during the 1950s, where programs were processed in arrival order to manage limited resources efficiently.[11] This adoption extended naturally to electronics by the mid-20th century for buffering data in digital circuits, establishing FIFO as a cornerstone of sequential processing across domains.[12]Comparison to Other Queues

A First-In, First-Out (FIFO) queue processes elements in the order they arrive, ensuring sequential preservation, which contrasts with the Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) structure, commonly implemented as a stack, where the most recently added element is removed first.[1] This LIFO behavior suits scenarios like recursion and backtracking, as seen in algorithms such as depth-first search, where undoing the latest operation aligns with reversing the most recent action. In contrast, FIFO maintains temporal order, making it ideal for modeling real-world lines or pipelines where earlier arrivals must be handled before later ones, without the reversal inherent in LIFO.[13] Compared to priority queues, FIFO operates on a strict temporal basis without evaluating element values, avoiding the overhead of priority assignment and sorting that priority queues require.[14] Priority queues, often using heaps, dequeue the highest-priority item regardless of arrival order, which introduces logarithmic time complexity for insertions and removals but enables value-based scheduling, such as in task management where urgency trumps sequence.[15] FIFO, by eschewing this evaluation, provides simpler, constant-time operations without reordering, though it lacks the flexibility for scenarios demanding preferential treatment.[16] FIFO offers advantages in fairness, as it allocates resources equally based on arrival without favoring newer or higher-value entries, promoting equitable processing in systems like operating system schedulers.[17] Its predictability stems from deterministic ordering, which is crucial in time-sensitive environments such as network buffering, where consistent delays aid in performance modeling. However, FIFO can suffer from head-of-line blocking, where a slow-processing element at the front delays subsequent ones, even if they could proceed faster, leading to inefficiencies in variable-latency scenarios like packet switching.[18]| Queue Type | Access Order | Typical Uses | Time Complexity (Enqueue/Dequeue) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIFO | First-In, First-Out | Sequential processing, buffering, breadth-first search | O(1) / O(1) |

| LIFO (Stack) | Last-In, First-Out | Recursion, backtracking, function calls | O(1) / O(1) |

| Priority Queue | Highest Priority First | Task scheduling, Dijkstra's algorithm, event simulation | O(log n) / O(log n) |

In Computing

Abstract Data Type

In computer science, a First-In-First-Out (FIFO) queue is formalized as an abstract data type (ADT) that models an ordered collection of elements, where insertion occurs at the rear (tail) and removal at the front (head), ensuring that elements are processed in the order of their arrival.[19] This ADT abstracts away implementation details, focusing instead on the behavioral interface and invariants that guarantee FIFO ordering./16%3A_Data_Structures-_Lists_Stacks_and_Queues/16.04%3A_Section_4-) The core operations of the FIFO queue ADT include:- Enqueue(e): Adds an element e to the rear of the queue.[20]

- Dequeue(): Removes and returns the element at the front of the queue.[20]

- Peek() (or front()): Returns the element at the front without removing it.[19]

- IsEmpty(): Checks if the queue contains no elements.[19]

- IsFull() (for bounded queues): Checks if the queue has reached its capacity.[21]

FIFOQueue:

createQueue() → Queue // Returns an empty queue

enqueue(Queue q, element e) → void // Adds e to rear of q

dequeue(Queue q) → element // Removes and returns front of q (raises underflow if empty)

peek(Queue q) → element // Returns front of q without removal (raises underflow if empty)

isEmpty(Queue q) → [boolean](/page/Boolean) // True if q has no elements

isFull(Queue q) → [boolean](/page/Boolean) // True if q is at capacity (for bounded queues)

FIFOQueue:

createQueue() → Queue // Returns an empty queue

enqueue(Queue q, element e) → void // Adds e to rear of q

dequeue(Queue q) → element // Removes and returns front of q (raises underflow if empty)

peek(Queue q) → element // Returns front of q without removal (raises underflow if empty)

isEmpty(Queue q) → [boolean](/page/Boolean) // True if q has no elements

isFull(Queue q) → [boolean](/page/Boolean) // True if q is at capacity (for bounded queues)

Software Implementations

Software implementations of FIFO queues commonly rely on arrays or linked lists to realize the abstract data type, balancing efficiency in time and space based on the expected usage patterns. An array-based implementation uses a linear array with two indices: head pointing to the front of the queue and tail to the rear. Enqueue operations increment the tail index and insert the element, while dequeue operations increment the head index and remove the element at that position. However, repeated dequeues lead to wasted space in the lower indices of the array, as elements shift rightward without reusing the freed space, potentially requiring periodic compaction to avoid overflow.[22] To address the space inefficiency, the circular queue variant employs modulo arithmetic to wrap indices around the array boundaries, allowing reuse of dequeued positions. The next tail index is calculated as (tail + 1) % size, where size is the array length, enabling the queue to utilize the full array capacity without shifting elements. This approach maintains the FIFO order while preventing the "rightward drift" issue of linear arrays, though it requires careful handling to distinguish between full and empty states, often using an additional flag or reserving one slot.[23] A linked list implementation represents each queue element as a node containing the data and a pointer to the next node, with head and tail pointers managing access. Enqueue adds a new node at the tail in constant time by updating the previous tail's pointer, and dequeue removes the head node by advancing the head pointer. This structure supports dynamic resizing without predefined limits, avoiding the fixed capacity constraints of arrays and eliminating wasted space entirely.[24] Both implementations achieve O(1) amortized time for enqueue and dequeue operations, with O(n space complexity proportional to the number of elements stored, where n is the queue size. Circular array-based queues offer faster random access due to contiguous memory, but require fixed initial sizing; linked lists provide better flexibility for varying sizes at the cost of higher memory overhead from pointers. The following table summarizes key trade-offs:| Aspect | Array-Based (Circular) | Linked List-based |

|---|---|---|

| Time per Operation | O(1) enqueue/dequeue | O(1) enqueue/dequeue |

| Space Efficiency | O(n, fixed size, no pointer overhead | O(n), dynamic but with pointer costs |

| Access Speed | Fast (direct indexing) | Slower (traversal via pointers) |

| Resizing | Requires reallocation if full | Automatic, no fixed limit |

std::queue as a container adaptor, typically implemented atop std::deque for efficient FIFO operations supporting push (enqueue) and pop (dequeue) in constant time. A basic usage example is:

#include <queue>

std::queue<int> q;

q.push(1); // Enqueue

int front = q.front(); // Peek

q.pop(); // Dequeue

#include <queue>

std::queue<int> q;

q.push(1); // Enqueue

int front = q.front(); // Peek

q.pop(); // Dequeue

collections.deque serves as an efficient FIFO queue with O(1) append and pop from both ends, implemented as a doubly-linked list of blocks for thread-safe, memory-efficient operations. For FIFO usage:

from collections import deque

q = deque()

q.append(1) # Enqueue

front = q[0] # Peek

q.popleft() # Dequeue

from collections import deque

q = deque()

q.append(1) # Enqueue

front = q[0] # Peek

q.popleft() # Dequeue

Applications

In operating systems, FIFO queues are fundamental to process scheduling through the First-Come, First-Served (FCFS) algorithm, where ready processes are maintained in a FIFO list and executed in the order of their arrival to ensure fairness and simplicity.[27][28] This approach minimizes overhead by avoiding complex prioritization, though it can lead to convoy effects where short processes wait behind long ones.[29] Similarly, I/O request queues employ FIFO to manage disk or device operations, queuing requests from processes in arrival order to prevent starvation and maintain predictable access patterns in systems like Unix-like kernels.[30][31] In networking, FIFO buffering is widely used in routers to handle packet transmission, storing incoming packets in a queue and forwarding them in the order received to preserve sequence integrity and avoid reordering delays.[32] This first-in, first-out discipline ensures reliable delivery in protocols like IP, where buffers at output interfaces drop excess packets only after saturation, supporting best-effort service without active queue management in basic setups.[33][34] FIFO structures play a key role in multithreading for solving the producer-consumer problem, where a shared bounded buffer operates as a FIFO queue to synchronize producers adding data and consumers removing it, preventing race conditions through mechanisms like semaphores or mutexes.[35] This ensures data integrity and order preservation in concurrent environments, such as in real-time operating systems where multiple threads exchange messages without overwriting.[36] Representative examples of FIFO application include breadth-first search (BFS) in graph algorithms, where a FIFO queue tracks nodes level by level, enqueueing neighbors of the current node and dequeuing in arrival order to explore shortest paths in unweighted graphs.[37] Another common use is in print job queues, where documents are spooled into a FIFO buffer and processed sequentially by the printer, guaranteeing that jobs print in submission order to avoid user confusion in shared environments like office networks.[38] A notable case study is the TCP/IP protocol's receive buffers, which use FIFO-like reassembly queues to temporarily hold out-of-order packets arriving due to varying network paths, buffering them until sequence gaps are filled for in-order delivery to the application layer.[39] This mechanism, part of TCP's reliable transport, mitigates disruptions from packet reordering while minimizing latency through selective acknowledgments.[40] As of 2025, emerging applications leverage FIFO in real-time systems for IoT data streams, such as queuing sensor inputs in edge devices to ensure timely, ordered processing in resource-constrained environments like smart grids or autonomous vehicles, where FIFO scheduling maintains low-latency guarantees over complex topologies.[41][42]In Electronics

Hardware Design

In electronic circuits, hardware FIFO buffers provide temporary data storage to manage flow between processing stages or domains with differing rates, commonly implemented as shift registers for fixed-depth, synchronous operations or as memory arrays like dual-port SRAM for scalable, circular queuing.[43] Shift register designs suit simple applications with limited capacity, while SRAM-based arrays enable deeper buffers by using addressable locations for efficient read and write access.[43] The core design goals of hardware FIFOs emphasize decoupling producer and consumer speeds to accommodate rate variations without halting upstream processes, and buffering to avert data loss in pipelined systems where input bursts exceed immediate output capacity.[43] This buffering role is essential in data-intensive circuits, ensuring reliable transfer without requiring precise timing alignment between modules.[43] Essential components include memory cells, typically SRAM for high-density storage; read and write pointers implemented as binary counters to maintain circular addressing and prevent overflow or underflow; and configurable depth, representing the number of storage stages, such as 16 words in early devices or 1024 words in larger variants.[43] These elements form a self-managing queue where pointers modulo the depth to wrap around, optimizing space utilization.[43] In VLSI design for embedded systems, power and area trade-offs are critical: static SRAM FIFOs minimize dynamic power through efficient pointer logic that scales linearly with depth, but large depths increase static leakage; conversely, fall-through architectures demand additional flip-flops per word for immediate status propagation, escalating area for depths beyond 64 stages and favoring SRAM hybrids in power-constrained applications.[43] Hardware FIFOs originated in the 1970s with discrete TTL logic devices like the SN74S225, a 16x5 asynchronous buffer using simple register chains, evolving to integrated SRAM-based designs in the 1980s and beyond for higher speeds and capacities.[43] Today, they are standard IP blocks in FPGAs and ASICs, instantiated via embedded block RAM in SoCs for applications like processor peripherals, with examples in Xilinx UltraScale devices supporting up to 76 Mbits of FIFO-configurable memory.[44]Synchronous Variants

Synchronous variants of FIFO buffers operate within a single clock domain, where both read and write operations are synchronized to the same clock signal, typically on the rising or falling edges.[43] This design enables concurrent read and write access without the need for clock domain crossing synchronization, making it suitable for pipelined systems where data flow must maintain strict timing alignment.[7] The unified clock ensures that all control signals, including enable flags and status indicators, are updated predictably within the same cycle.[45] The core circuit structure utilizes a dual-port RAM to allow simultaneous read and write operations to the memory array, paired with binary counters for the read and write pointers that address specific locations.[43] These pointers increment on active clock edges when their respective enables are asserted, wrapping around circularly to reuse memory space.[45] To prevent ambiguity between empty and full states—both of which occur when pointers align—an extra most significant bit (MSB) is appended to each pointer, effectively doubling the addressable space and allowing differentiation: empty when pointers are identical including the extra bit, and full when the lower bits match but the extra bit differs.[45] Synchronous FIFOs offer advantages such as simplified logic design and the elimination of metastability risks, since no signals cross asynchronous boundaries and all comparisons occur within the same clock cycle.[46] Pointer comparison for status is straightforward; for instance, the FIFO is full when the write pointer minus the read pointer equals the buffer depth: \text{full} = (\text{write_ptr} - \text{read_ptr}) \mod 2^{n+1} = \text{depth} where is the bit width of the address pointers excluding the extra bit.[47] This approach supports high-throughput operation, with fall-through latency independent of buffer size for large memories.[43] In CPU pipelines, synchronous FIFOs serve as instruction or data buffers to decouple fetch and execute stages, ensuring smooth data progression without stalls due to timing mismatches.[43] Similarly, in DSP filters, they manage sequential sample buffering for operations like finite impulse response (FIR) processing, maintaining order in real-time signal streams.[43] A key drawback is their confinement to environments with matching clock speeds for read and write domains, limiting flexibility in heterogeneous systems where frequency variations are common.[43] For illustration, consider a basic timing diagram for an 8-entry synchronous FIFO: at clock cycle 1 (rising edge), with write enable high and FIFO empty, data D0 is written, write pointer advances from 0 to 1, and empty deasserts; at cycle 2, simultaneous read and write occur (read enable high), outputting D0 while storing D1, advancing both pointers to 1 and 2, respectively, with neither full nor empty asserted until subsequent cycles fill the depth.[7]Asynchronous Variants

Asynchronous variants of FIFO buffers operate across distinct clock domains, employing separate write and read clocks to facilitate data transfer between asynchronous systems. Unlike synchronous designs, these FIFOs use handshaking protocols or multi-stage synchronizers to manage pointer transfers, ensuring reliable operation despite clock skew and phase differences. This approach is essential for clock domain crossing (CDC) in multi-clock environments, where data integrity must be preserved without a common timing reference.[48] A common implementation involves Gray code pointers for the write (wptr) and read (rptr) addresses, which change only one bit at a time to minimize synchronization errors during cross-domain transfer. The pointers are synchronized using dual flip-flop stages (e.g., two flip-flops per bit) in each direction—write-to-read and read-to-write—to resolve metastability, with the synchronized values used to generate full and empty flags via asynchronous comparison logic. For safe depth, the FIFO size is typically a power of 2 (e.g., 2^(n-1) for n-bit pointers). The FIFO depth must be sized to handle the maximum expected burst length plus additional margin for synchronization delays (typically 4-6 words for 2-stage synchronizers) and rate differences between clock domains. Metastability is further addressed using techniques like Muller C-elements for mutual exclusion in pointer updates or toggle synchronizers (even/odd schemes) that alternate register writes to bound phase uncertainty.[48][49][50][51] These designs enable seamless CDC in system-on-chip (SoC) architectures, allowing integration of heterogeneous IP blocks with varying clock rates, such as in processors interfacing with peripherals. However, they introduce higher latency from synchronization stages (typically 2-4 clock cycles per direction) and increased area overhead due to additional flip-flops and logic compared to single-clock variants. In modern applications as of 2025, asynchronous FIFOs are integral to high-speed interfaces in 5G and emerging 6G networks, supporting reconfigurable data flows in IoT and cyber-physical systems for low-latency, high-bandwidth transmission.[52][48][51]Interface and Status Mechanisms

Hardware First-In-First-Out (FIFO) buffers employ standardized interface signals and status flags to facilitate controlled data transfer between producers and consumers, ensuring reliable operation in digital systems. These mechanisms allow external logic to monitor the FIFO's state and coordinate read and write operations without risking data corruption. The primary status flags include the empty flag, which asserts when no data is present in the buffer, preventing invalid reads, and the full flag, which indicates that the buffer has reached capacity, avoiding writes that would overwrite existing data.[43][53] Additional threshold-based flags, such as almost empty and almost full, provide early warnings when the buffer occupancy approaches critical levels, enabling preemptive actions like throttling input rates or prioritizing outputs to maintain smooth data flow.[54][55] Core interface protocols revolve around control signals that govern data ingress and egress. The write enable signal activates data loading into the FIFO when asserted, typically alongside input data lines of fixed width (e.g., 8 to 256 bits), while the read enable signal triggers data retrieval from the output when the buffer is not empty.[56][57] A data valid strobe often accompanies the output data to confirm its readiness for consumption, ensuring synchronization in pipelined designs. These signals operate synchronously with the FIFO's clock in basic implementations, supporting burst transfers up to the buffer's depth. In asynchronous FIFOs, where read and write domains use independent clocks, handshaking protocols enhance robustness by decoupling transfer rates. The ready/valid protocol is commonly used: the producer asserts a valid signal with data, and the consumer responds with a ready signal; transfer completes only when both are high, allowing backpressure to prevent overflows across clock boundaries.[58][59] This two-way handshake supports high-throughput streaming without requiring immediate acknowledgment, making it suitable for rate-adaptive systems. Field-programmable gate array (FPGA) implementations frequently adopt standardized bus protocols for FIFO interfaces to simplify integration. For instance, the Avalon Streaming (Avalon-ST) interface from Intel uses start-of-packet and end-of-packet signals alongside data and valid strobes to handle packetized flows, with backpressure via a backpressure signal equivalent to ready.[60] Similarly, the AXI4-Stream protocol from ARM/AMD employs TVALID (data valid) and TREADY (ready) for handshaking, with sideband signals like TLAST for packet delimitation, enabling seamless FIFO buffering in SoC designs.[61][62] To aid debugging and error detection, hardware FIFOs incorporate logic for monitoring overflow (attempted write to full buffer) and underflow (attempted read from empty buffer) conditions, often generating interrupt or status bits that halt operations or assert error flags.[63] These detections rely on pointer comparisons internal to the FIFO but expose user-visible indicators, allowing system-level diagnostics to identify mismatches in data rates or protocol violations.References

- https://cio-wiki.org/wiki/First-In_First-Out