Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Colorectal polyp

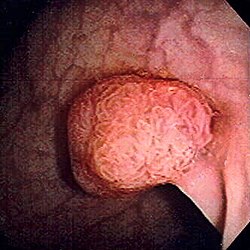

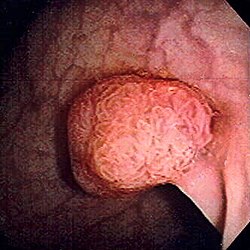

View on Wikipedia| Colon polyps | |

|---|---|

| |

| Polyp of sigmoid colon as revealed by colonoscopy. Approximately 1 cm in diameter. The polyp was removed by snare cautery. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

A colorectal polyp is a polyp (fleshy growth) occurring on the lining of the colon or rectum.[1] Untreated colorectal polyps can develop into colorectal cancer.[2]

Colorectal polyps are often classified by their behaviour (i.e. benign vs. malignant) or cause (e.g. as a consequence of inflammatory bowel disease). They may be benign (e.g. hyperplastic polyp), pre-malignant (e.g. tubular adenoma) or malignant (e.g. colorectal adenocarcinoma).

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Colorectal polyps are not usually associated with symptoms.[2] When they occur, symptoms include bloody stools; changes in frequency or consistency of stools (such as a week or more of constipation or diarrhoea);[3] and fatigue arising from blood loss.[2] Anemia arising from iron deficiency can also present due to chronic blood loss, even in the absence of bloody stools.[3][4] Another symptom may be an increased mucus production especially those involving villous adenomas.[4] Copious production of mucus causes loss of potassium that can occasionally result in symptomatic hypokalemia.[4] Occasionally, if a polyp is big enough to cause a bowel obstruction, there may be nausea, vomiting and severe constipation.[3]

Structure

[edit]Polyps are either pedunculated (attached to the intestinal wall by a stalk) or sessile (grow directly from the wall).[5][6]: 1342 In addition to the gross appearance categorization, they are further divided by their histologic appearance as tubular adenoma which are tubular glands, villous adenoma which are long finger like projections on the surface, and tubulovillous adenoma which has features of both.[6]: 1342

Genetics

[edit]Hereditary syndromes causing increased colorectal polyp formation include:

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)[7]

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

- Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

- Juvenile polyposis syndrome

Several genes have been associated with polyposis, such as GREM1, MSH3, MLH3, NTHL1, RNF43 and RPS20.[8]

Familial adenomatous polyposis

[edit]Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a form of hereditary cancer syndrome involving the APC gene located on chromosome q521.[9] The syndrome was first described in 1863 by Virchow on a 15-year-old boy with multiple polyps in his colon.[9] The syndrome involves development of multiple polyps at an early age and those left untreated will all eventually develop cancer.[9] The gene is expressed 100% in those with the mutation and it is autosomal dominant.[9] 10–20% of patients have negative family history and acquire the syndrome from spontaneous germline mutation.[9] The average age of newly diagnosed patient is 29 and the average age of newly discovered colorectal cancer is 39.[9] It is recommended that those affected undergo colorectal cancer screening at younger age with treatment and prevention are surgical with removal of affected tissues.[9]

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch Syndrome)

[edit]Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, also known as Lynch syndrome) is a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome.[9] It is the most common hereditary form of colorectal cancer in the United States and accounts for about 3% of all cases of cancer.[9] It was first recognized by Alder S. Warthin in 1885 at the University of Michigan.[9] It was later further studied by Henry Lynch who recognized an autosomal dominant transmission pattern with those affected having relatively early onset of cancer (mean age 44 years), greater occurrence of proximal lesions, mostly mucinous or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, greater number of synchronous and metachronous cancer cells, and good outcome after surgical intervention.[9] The Amsterdam Criteria were initially used to define Lynch syndrome before the underlying genetic mechanism had been worked out.[9] The Criteria required that the patient has three family members all first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer that involves at least two generations with at least one affected person being younger than 50 years of age when the diagnosis was made.[9] The Amsterdam Criteria is too restrictive and was later expanded to include cancers of endometrial, ovarian, gastric, pancreatic, small intestinal, ureteral, and renal pelvic origin.[9] The increased risk of cancer seen in patients with by the syndrome is associated with dysfunction of DNA repair mechanism.[9] Molecular biologists have linked the syndrome to specific genes such as hMSH2, hMSH1, hMSH6, and hPMS2.[9]

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

[edit]Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome that presents with hamartomatous polyps, which are disorganized growth of tissues of the intestinal tract, and hyperpigmentation of the interlining of the mouth, lips and fingers.[9] The syndrome was first noted in 1896 by Hutchinson, and later separately described by Peutz, and then again in 1940 by Jeghers.[9] The syndrome is associated with malfunction of serine-threonine kinase 11 or STK 11 gene, and has a 2–10% increase in risk of developing cancer of the intestinal tract.[9] The syndrome also causes increased risk of extraintestinal cancer such as that involving breast, ovary, cervix, fallopian tubes, thyroid, lung, gallbladder, bile ducts, pancreas, and testicles.[9] The polyps often bleeds and may cause obstruction that would require surgery.[9] Any polyp larger than 1.5 cm needs removal and patients should be monitored closely and screen every two years for malignancy.[9]

Juvenile polyposis syndrome

[edit]Juvenile polyposis syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by increased risk of cancer of intestinal tract and extraintestinal cancer.[9] It often presents with bleeding and obstruction of the intestinal tract along with low serum albumin due to protein loss in the intestine.[9] The syndrome is linked to malfunction of SMAD4 a tumor suppression gene that is seen in 50% of cases.[9] Individuals with multiple juvenile polyps have at least 10% chance of developing malignancy and should undergo abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, and close monitoring via endoscopy of rectum.[9] For individuals with few juvenile polyps, patients should undergo endoscopic polypectomy.[9]

Types

[edit]

Colorectal polyps can broadly be classified as follows:

- hyperplastic,

- neoplastic (adenomatous and malignant),

- hamartomatous and,

- inflammatory.

Comparison table

[edit]| Type | Risk of containing malignant cells | Histopathology | Image | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperplastic polyp | 0% | No dysplasia.[10]

|

| |

| Tubular adenoma | 2% at 1.5 cm[12] | Low to high grade dysplasia[13] | Over 75% of volume has tubular appearance.[14] |

|

| Tubulovillous adenoma | 20% to 25%[15] | 25–75% villous[14] |

| |

| Villous adenoma | 15%[16] to 40%[15] | Over 75% villous[14] |

| |

| Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA)[17] |

|

| ||

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma | 100% |

|

| |

Hyperplastic polyp

[edit]Most hyperplastic polyps are found in the distal colon and rectum.[18] They have no malignant potential,[18] which means that they are no more likely than normal tissue to eventually become a cancer.

Neoplastic polyp

[edit]A neoplasm is a tissue whose cells have lost normal differentiation. They can be either benign growths or malignant growths. The malignant growths can either have primary or secondary causes. Adenomatous polyps are considered precursors to cancer and cancer becomes invasive once malignant cells cross the muscularis mucosa and invade the cells below.[9] Any cellular changes seen above the lamina propria are considered non-invasive and are labeled atypia or dysplasia. Any invasive carcinoma that has penetrated the muscularis mocos has the potential for lymph node metastasis and local recurrence which will require more aggressive and extensive resection.[9] The Haggitt's criteria is used for classification of polyps containing cancer and is based on the depth of penetration.[9] The Haggitt's criteria has level 0 through level 4, with all invasive carcinoma of sessile polyp variant by definition being classified as level 4.[9]

- Level 0: Cancer does not penetrate through the muscularis mucosa.[9]

- Level 1: Cancer penetrates through the muscularis mucosa and invades the submucosa below but is limited to the head of the polyp.[9]

- Level 2: Cancer invades through with involvement of the neck of polyp.[9]

- Level 3: Cancer invades through with involvement of any parts of the stalk.[9]

- Level 4: Cancer invades through the submucosa below the stalk of the polyp but above the muscularis propria of the bowel wall.[9]

Adenomas

[edit]Neoplastic polyps of the bowel are often benign hence called adenomas. An adenoma is a tumor of glandular tissue, that has not (yet) gained the properties of cancer.[citation needed]

The common adenomas of the colon (colorectal adenoma) are the tubular, tubulovillous, villous, and sessile serrated (SSA).[18] A large majority (65–80%) are of the benign tubular type with 10–25% being tubulovillous, and villous being the most rare at 5–10%.[9]

As is evident from their name, sessile serrated and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) have a serrated appearance and can be difficult to distinguish microscopically from hyperplastic polyps.[18] Making this distinction is important, however, since SSAs and TSAs have the potential to become cancers,[19] while hyperplastic polyps do not.[18]

The villous subdivision is associated with the highest malignant potential because they generally have the largest surface area. (This is because the villi are projections into the lumen and hence have a bigger surface area.) However, villous adenomas are no more likely than tubular or tubulovillous adenomas to become cancerous if their sizes are all the same.[18]

Hamartomatous polyp

[edit]Hamartomatous polyps are tumours, like growths found in organs as a result of faulty development. They are normally made up of a mixture of tissues. They contain mucus-filled glands, with retention cysts, abundant connective tissue, and chronic cellular infiltration of eosinophils.[20] They grow at the normal rate of the host tissue and rarely cause problems such as compression. A common example of a hamartomatous lesion is a strawberry naevus. Hamartomatous polyps are often found by chance; occurring in syndromes such as Peutz–Jegher syndrome or Juvenile polyposis syndrome.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is associated with polyps of the GI tract and also increased pigmentation around the lips, genitalia, buccal mucosa, feet, and hands. People are often diagnosed with Peutz–Jegher after presenting at around the age of nine with an intussusception. The polyps themselves carry little malignant potential but because of potential coexisting adenomas there is a 15% chance of colonic malignancy.

Juvenile polyps are hamartomatous polyps that often become evident before twenty years of age, but can also be seen in adults. They are usually solitary polyps found in the rectum which most commonly present with rectal bleeding. Juvenile polyposis syndrome is characterised by the presence of more than five polyps in the colon or rectum, or numerous juvenile polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract, or any number of juvenile polyps in any person with a family history of juvenile polyposis. People with juvenile polyposis have an increased risk of colon cancer.[19]

Inflammatory polyp

[edit]These are polyps that are associated with inflammatory conditions such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease.[citation needed]

Prevention

[edit]Diet and lifestyle are believed to play a large role in whether colorectal polyps form. Studies show there to be a protective link between consumption of cooked green vegetables, brown rice, legumes, and dried fruit and decreased incidence of colorectal polyps.[21]

Diagnosis

[edit]Colorectal polyps can be detected using a faecal occult blood test, flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, virtual colonoscopy, digital rectal examination, barium enema or a pill camera.[3][failed verification]

Malignant potential is associated with

- degree of dysplasia

- Type of polyp (e.g. villous adenoma):

- Tubular adenoma: 5% risk of cancer

- Tubulovillous adenoma: 20% risk of cancer

- Villous adenoma: 40% risk of cancer

- Size of polyp:

Normally an adenoma that is greater than 0.5 cm is treated.

Gallery

[edit]

-

Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp. H&E stain.

-

Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp. H&E stain.

-

Traditional serrated adenoma. H&E stain.

-

Gross appearance of a colectomy specimen containing two colorectal polyps and one invasive colorectal carcinoma

-

Micrograph of a tubular adenoma, the most common type of dysplastic polyp in the colon

-

Micrograph of a tubular adenoma – dysplastic epithelium (dark purple) on left of image; normal epithelium (blue) on right. H&E stain.

-

Micrograph of a villous adenoma. These polyps are considered to have a high risk of malignant transformation. H&E stain.

-

Paris classification of colorectal neoplasms[23]

NICE classification

[edit]In colonoscopy, colorectal polyps can be classified by NICE (Narrow-band imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic):[24]

| Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Same or lighter than background | Browner than background | Browner or darkly browner than background, sometimes patchy whiter areas |

| Vessels | None, or isolated lacy vessels coursing across the lesion | Brown vessels surrounding white structures | Area of disrupted or missing vessels |

| Surface Pattern | Homogenous, or dark or white spots of uniform size | Oval, tubular or branched white structures surrounded by brown vessels | Amorphous or absent surface pattern |

| Most likely pathology | Hyperplasia | Adenoma | Deep submucosal invasive cancer |

| Treatment | Follow up | Mucosal or submucosal polypectomy | Surgical operation |

Treatment

[edit]Polyps can be removed during a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy using a wire loop that cuts the stalk of the polyp and cauterises it to prevent bleeding.[3][failed verification] Many "defiant" polyps—large, flat, and otherwise laterally spreading adenomas—may be removed endoscopically by a technique called endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), which involves injection of fluid underneath the lesion to lift it and thus facilitate endoscopic resection. Saline water may be used to generate lift, though some injectable solutions such as SIC 8000 may be more effective.[25] Minimally invasive surgery is indicated for polyps that are too large or in unfavorable locations, such as the appendix, that cannot be removed endoscopically.[26] These techniques may be employed as an alternative to the more invasive colectomy.[27]

Follow-up

[edit]By United States guidelines, the following follow-up is recommended:[28]

| Baseline colonoscopy finding | Recommended time until next colonoscopy |

|---|---|

| Normal | 10 years |

| 1–2 tubular adenomas <10 mm | 7–10 years |

| 3–4 tubular adenomas <10 mm | 3–5 years |

|

3 years |

| >10 adenomas on single examination | 1 year |

| Piecemeal resection of adenoma 20 mm | 6 months |

References

[edit]- ^ Marks, Jay W.; Anand, Bhupinder. "Colon Polyps: Symptoms, Causes, Cancer Risk, Treatment, and Prevention". Colon polyps center. MedicineNet. Retrieved 18 Jan 2020.

- ^ a b c Phillips, Michael M.; Zieve, David; Conaway, Brenda (September 25, 2019). "Colorectal polyps". Medical Encyclopedia. MedlinePlus. Retrieved 18 Jan 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Colon polyps". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Retrieved 18 Jan 2020.

- ^ a b c Quick CR, Reed JB, Harper SJ, Saeb-Parsy K, Burkitt HG (2014). Essential Surgery: Problems, Diagnosis and Management. Edinburgh: Elsevier. ISBN 9780702054839. OCLC 842350865.[page needed]

- ^ Classen, Meinhard; Tytgat, G.N.J.; Lightdale, Charles J. (2002). Gastroenterological Endoscopy. Thieme. p. 303. ISBN 1-58890-013-4.

- ^ a b Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. (2015). Sabiston Textbook of Surgery E-Book (19th ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-1560-6 – via Google Books (Preview).

- ^ "Familial Adenomatous Polyposis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Valle L, de Voer RM, Goldberg Y, Sjursen W, Försti A, Ruiz-Ponte C, Caldés T, Garré P, Olsen MF, Nordling M, Castellvi-Bel S, Hemminmki K (October 2019). "Update on genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer and polyposis". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 69. Elsevier: 10–26. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2019.03.001. hdl:2445/171217. PMID 30862463.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Mahmoud, Najjia N.; Bleier, Joshua I.S.; Aarons, Cary B.; Paulson, E. Carter; Shanmugan, Skandan; Fry, Robert D. (2017). Sabiston Textbook of Surgery (20th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 9780323401630.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Finlay A Macrae. "Overview of colon polyps". UpToDate. This topic last updated: Dec 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c Robert V Rouse (2010-01-31). "Hyperplastic Polyp of the Colon and Rectum". Stanford University School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2019-10-31. Last updated 6/2/2015

- ^ Minhhuyen Nguyen. "Polyps of the Colon and Rectum". MSD Manual. Last full review/revision June 2019

- ^ Robert V Rouse. "Adenoma of the Colon and Rectum". Archived from the original on 2019-09-11. Retrieved 2019-10-31. Original posting/last update : 1/31/10, 1/19/14

- ^ a b c Bosman, F. T. (2010). WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. ISBN 978-92-832-2432-7. OCLC 688585784.

- ^ a b Amersi, Farin; Agustin, Michelle; Ko, Clifford Y (2005). "Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Health Services". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 18 (3): 133–140. doi:10.1055/s-2005-916274. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 2780097. PMID 20011296.

- ^ Alnoor Ramji (22 December 2022). "Villous Adenoma Follow-up". Medscape. Updated: Oct 24, 2016

- ^ Rosty, C; Hewett, D. G.; Brown, I. S.; Leggett, B. A.; Whitehall, V. L. (2013). "Serrated polyps of the large intestine: Current understanding of diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical management". Journal of Gastroenterology. 48 (3): 287–302. doi:10.1007/s00535-012-0720-y. PMC 3698429. PMID 23208018.

- ^ a b c d e f Kumar, Vinay (2010). "17—Polyps". Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5.

- ^ a b Stoler, Mark A.; Mills, Stacey E.; Carter, Darryl; Joel K. Greenson; Reuter, Victor E. (2009). Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7942-5.[page needed]

- ^ Calva, Daniel; Howe, James R (2008). "Hamartomatous Polyposis Syndromes". Surgical Clinics of North America. 88 (4): 779–817, vii. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2008.05.002. PMC 2659506. PMID 18672141.

- ^ Tantamango, Yessenia M; Knutsen, Synnove F; Beeson, W Lawrence; Fraser, Gary; Sabate, Joan (2011). "Foods and Food Groups Associated with the Incidence of Colorectal Polyps: The Adventist Health Study". Nutrition and Cancer. 63 (4): 565–72. doi:10.1080/01635581.2011.551988. PMC 3427008. PMID 21547850.

- ^ a b c Summers, Ronald M (2010). "Polyp Size Measurement at CT Colonography: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know?". Radiology. 255 (3): 707–20. doi:10.1148/radiol.10090877. PMC 2875919. PMID 20501711.

- ^ Luis Bujanda Fernández de Piérola, Joaquin Cubiella Fernández, Fernando Múgica Aguinaga, Lander Hijona Muruamendiaraz and Carol Julyssa Cobián Malaver (2013). "Malignant Colorectal Polyps: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prognosis". Colonoscopy and Colorectal Cancer Screening: Future Directions. doi:10.5772/52697. ISBN 9789535109495.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License - ^ Hattori, Santa (2014). "Narrow-band imaging observation of colorectal lesions using NICE classification to avoid discarding significant lesions". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 6 (12): 600–605. doi:10.4253/wjge.v6.i12.600. PMC 4265957. PMID 25512769.

- ^ Hoff, RT; Lakha, A (1 February 2020). "Rectal Tubulovillous Adenoma". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 120 (2): 121. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2020.024. PMID 31985762.

- ^ Fisichella, M. (2016). "Laparoscopic Cecal Wedge Resection Appendectomy". J Med Ins: 207. doi:10.24296/jomi/207.

- ^ Saunders B, Ginsberg GG, Bjorkman DJ (2008). "How I do it: Removing large or sessile colonic polyps" (PDF). Munich: OMED. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-11.

- ^ Gupta, Samir; Lieberman, David; Anderson, Joseph C.; Burke, Carol A.; Dominitz, Jason A.; Kaltenbach, Tonya; Robertson, Douglas J.; Shaukat, Aasma; Syngal, Sapna; Rex, Douglas K. (2020). "Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 91 (3): 463–485.e5. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.01.014. ISSN 0016-5107. PMC 7389642. PMID 32044106.

External links

[edit]Colorectal polyp

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and characteristics

A colorectal polyp is defined as an abnormal growth that protrudes from the mucous membrane lining the colon or rectum. These growths are typically benign, though some have the potential to become malignant over time.[3] Polyps can occur anywhere along the large intestine, including the proximal colon (cecum, ascending, and transverse segments), distal colon (descending and sigmoid segments), or rectum, with their location influencing detection and management approaches.[4] Colorectal polyps vary in size, commonly classified as diminutive (less than 5 mm in diameter), small (6-9 mm), or large (10 mm or greater), which helps assess clinical significance.[4] Morphologically, they appear as either pedunculated, with a stalk connecting the growth to the mucosal surface, or sessile, featuring a broad-based attachment without a stalk.[5] In the general population, the prevalence of colorectal polyps is approximately 25-30% among adults aged 50 years and older, based on screening colonoscopy data, while autopsy studies indicate rates up to 50% by age 70.[6] The understanding of colorectal polyps advanced significantly with the introduction of colonoscopy in the 1960s, enabling direct visualization and removal, which marked a shift from earlier indirect diagnostic methods.[7] Certain polyps, particularly adenomatous ones, play a key role in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence leading to colorectal cancer.[8]Epidemiology and risk factors

Colorectal polyps are detected in approximately 20-30% of screening colonoscopies in Western countries, with prevalence rates reaching up to 30% in population and autopsy studies among middle-aged and elderly individuals.[9] In contrast, detection rates are lower in Asia and Africa, estimated at 10-15%.[10] Globally, the prevalence of colorectal adenomas, a common type of polyp, is about 23.9% based on systematic reviews of screening data.[11] These geographic variations reflect differences in dietary habits, screening practices, and genetic factors. The incidence of colorectal polyps increases with age, remaining rare under 40 years but rising sharply thereafter, with detection rates of 21-28% in individuals aged 50-59 years, 41-45% in those aged 60-69 years, and 53-58% in those over 70 years.[12] Recent expansions in screening to age 45 have led to increased polyp detection in younger adults, with rates of approximately 25-27% in ages 45-54 as of 2025, aligning with rising early-onset colorectal cancer trends.[13][14] Demographic patterns show higher prevalence in males compared to females, with men exhibiting an odds ratio of approximately 1.68 for distal lesions.[15] Racial and ethnic differences also influence risk, with higher rates observed among Caucasians and African Americans relative to Hispanic or Asian populations; for instance, African Americans have a 1.2- to 2-fold increased risk for proximal lesions.[15] Familial clustering is evident, where a family history of polyps elevates individual risk independent of specific syndromes.[16] Modifiable risk factors significantly contribute to polyp development. Obesity, particularly with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m², increases the risk by 1.5- to 2-fold, with even higher odds (up to 4.26) for severe obesity (BMI ≥40).[15] Smoking, especially with 20 or more pack-years, approximately doubles the risk, with relative risks around 2.14 for current smokers.[15] Dietary factors play a key role, as high consumption of red and processed meats is associated with a relative risk of 1.2-1.5, while low fiber intake exacerbates this vulnerability.[16] Protective factors include regular physical activity, which can reduce polyp risk by about 30%.[17] Recent trends indicate declining rates of advanced neoplasia and colorectal cancer in populations with widespread screening programs, attributed to the preventive effect of polypectomy. In the United States, post-2000 screening initiatives contributed to a 20-30% drop in advanced neoplasia rates (as observed in early 2010s studies), though overall colorectal cancer incidence declines have slowed to approximately 1% per year as of 2023.[18][19]Clinical Presentation

Signs and symptoms

Most colorectal polyps are asymptomatic, especially when small, and are typically discovered incidentally during routine screening for colorectal cancer. The vast majority—over 90%—of such polyps are detected in asymptomatic individuals via procedures like colonoscopy.[1][20] When symptoms arise, they often stem from bleeding or the physical presence of larger polyps. Rectal bleeding is the most frequent manifestation, appearing as bright red blood on toilet paper or in the stool for distal polyps located in the sigmoid colon or rectum, while proximal polyps in the ascending colon may cause occult (hidden) bleeding or dark, tarry stools (melena) due to slower blood transit and degradation.[1][20] Changes in bowel habits, including persistent constipation or diarrhea lasting more than a week, can occur with sizable polyps that partially obstruct the bowel lumen or produce excess mucus.[1][2] Chronic, low-grade blood loss from any polyps may lead to iron-deficiency anemia, presenting with symptoms such as fatigue, pallor, and shortness of breath. Chronic or acute bleeding from polyp ulceration may result in severe anemia.[20][2] Rare acute presentations are associated with giant polyps exceeding 4 cm, which can trigger intestinal obstruction or intussusception—a condition where one segment of bowel telescopes into another—resulting in crampy abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting, and constipation.[21] Pedunculated polyps, with their stalk-like attachment, may also cause localized abdominal pain if they twist or become torsed.[1][2] Symptom profiles differ by polyp location: distal lesions more commonly produce noticeable bright red bleeding owing to their nearer position to the anus, whereas proximal polyps are generally less likely to cause overt symptoms and instead contribute to insidious issues like anemia from undetected blood loss.[20][2]Complications

Colorectal polyps, particularly adenomatous types, pose a significant risk of malignant transformation via the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, where benign growths progressively accumulate genetic alterations leading to invasive cancer.[8] This process typically spans 7 to 15 years from adenoma inception to cancer development, though high-risk adenomas—such as those with villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or size greater than 1 cm—may progress within 5 to 10 years.[22][23] The malignancy risk escalates with polyp size: approximately 1% for lesions under 1 cm, 10% for those 1 to 2 cm, and up to 50% for polyps exceeding 2 cm in diameter.[24] Non-malignant complications from untreated polyps are less common but can be serious. Chronic or acute bleeding from polyp ulceration may result in severe anemia. Intestinal obstruction occurs rarely, though it is more frequent in juvenile polyps or polyposis syndromes due to polyp bulk or multiplicity. Perforation during polyp growth is extremely rare, typically limited to isolated case reports involving large or inflammatory lesions. Sessile serrated lesions follow a distinct serrated neoplastic pathway to cancer, often driven by early BRAF mutations, which promote CpG island methylator phenotype progression and microsatellite instability.[25] These polyps contribute to 15-30% of colorectal cancers and carry a slower but insidious risk if undetected.[26] Undetected colorectal polyps account for over 95% of colorectal cancers, underscoring their role in preventable mortality when screening and removal are neglected.[27]Pathology

Histological structure

Colorectal polyps arise from the epithelial lining of the colonic mucosa, forming exophytic or sessile projections that can be neoplastic or non-neoplastic in nature.[28] Neoplastic polyps, primarily adenomas, exhibit glandular architecture derived from dysplastic colonic epithelium, while non-neoplastic polyps display reactive or disorganized mucosal components without dysplasia.[29] Microscopically, these lesions are evaluated for architectural patterns and cellular atypia to distinguish their potential behavior. In adenomatous polyps, the hallmark is a proliferation of dysplastic glands resembling colonic mucosa but with aberrant growth. Tubular adenomas feature closely packed, branching tubular glands with round to oval lumina, often showing a pedunculated or sessile configuration.[30] Villous adenomas display elongated, finger-like villous fronds with fibrovascular cores lined by tall columnar cells, whereas tubulovillous adenomas combine both patterns, with 25-75% villous component.[31] Dysplasia is graded using a two-tiered system: low-grade dysplasia involves mild architectural distortion, such as pseudostratification and loss of nuclear polarity, with cytological features like hyperchromasia and small nucleoli; high-grade dysplasia shows marked atypia, including complex glandular crowding, cribriforming, increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, and prominent nucleoli, indicating a higher risk of progression.[32] Non-neoplastic polyps lack dysplastic changes and include hyperplastic, inflammatory, and hamartomatous types. Hyperplastic polyps demonstrate a serrated glandular architecture with saw-tooth-like crypts confined to the upper half of the epithelium, featuring microvesicular mucin in cells and no basal crypt branching.[33] Inflammatory pseudopolyps consist of inflamed and eroded surface mucosa with expanded lamina propria containing mixed inflammatory infiltrates, crypt abscesses, and granulation tissue featuring dilated thin-walled vessels and fibrosis.[34] Hamartomatous polyps, such as juvenile polyps, are characterized by disorganized, cystically dilated glands filled with mucus and inflammatory debris, embedded in edematous stroma rich in lymphocytes and plasma cells.[35] Histological diagnosis relies primarily on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, which highlights epithelial architecture, glandular patterns, and cytological atypia for routine evaluation.[28] Special stains, such as Ki-67 immunohistochemistry, assess proliferative activity by revealing nuclear staining in epithelial cells, often showing an expanded basal proliferative zone in adenomas or irregular foci in serrated lesions to aid in distinguishing subtle dysplasia.[36]Genetic and molecular basis

The development of colorectal polyps involves a series of somatic genetic mutations that drive initiation and progression, particularly in sporadic adenomas. Inactivating mutations in the APC gene occur in approximately 80% of sporadic adenomas and represent an early initiating event by disrupting the Wnt signaling pathway, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation.[37] Progression to advanced adenomas is often marked by activating mutations in the KRAS oncogene in 30-50% of cases, which enhance downstream signaling in the MAPK pathway and promote growth.[38] In late-stage lesions approaching carcinoma, loss-of-function mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene accumulate, impairing DNA repair and apoptosis, further destabilizing the genome.[39] Two primary molecular pathways underlie polyp formation and malignant transformation: the classic adenoma-carcinoma sequence driven by chromosomal instability (CIN) and the serrated neoplasia pathway characterized by epigenetic alterations. The CIN pathway, responsible for most conventional adenomas, features progressive accumulation of chromosomal aberrations, including aneuploidy and loss of heterozygosity, often initiated by APC inactivation and culminating in widespread genomic instability.[40] In contrast, the serrated pathway predominates in sessile serrated lesions and involves the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), where hypermethylation silences tumor suppressor genes, combined with the BRAF V600E mutation in about 80% of sessile serrated polyps, activating the MAPK pathway independently of KRAS.[41] This pathway frequently leads to microsatellite instability through MLH1 promoter methylation. Hereditary syndromes account for a subset of polyps with distinct genetic bases, predisposing individuals to polyposis through germline mutations. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) arises from germline APC mutations, resulting in hundreds to thousands of adenomas typically by the second decade of life, with near-certain progression to colorectal cancer if untreated.[42] Lynch syndrome, caused by germline defects in DNA mismatch repair genes such as MLH1 or MSH2, confers a 70-80% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, often through fewer but rapidly progressing adenomas exhibiting microsatellite instability.[37] Peutz-Jeghers syndrome stems from STK11 germline mutations, leading to hamartomatous polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract accompanied by mucocutaneous melanin pigmentation.[43] Juvenile polyposis syndrome involves germline mutations in SMAD4 or BMPR1A, which disrupt TGF-β signaling and cause multiple (typically 5 or more, but ranging from a few to hundreds) hamartomatous polyps primarily in the colorectum, increasing cancer risk over time.[44] Recent advances highlight the interplay of environmental factors and emerging detection technologies in polyp pathogenesis. By 2025, studies have elucidated the gut microbiome's role in promoting serrated lesion formation, with dysbiotic communities enriched in Fusobacterium nucleatum and certain Bacteroides species fostering inflammation and BRAF activation in susceptible individuals.[45] Additionally, liquid biopsy techniques detecting circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) have shown promise for non-invasive polyp surveillance, with reported sensitivities for advanced adenomas around 23% in recent multimodal assays through methylation or mutation profiling, though specificity remains a challenge for early lesions.[46]Classification

Major types

Colorectal polyps are broadly classified into neoplastic and non-neoplastic categories based on their histological features and potential for malignant transformation. Neoplastic polyps, which are precancerous, include adenomas and serrated lesions, while non-neoplastic polyps lack this malignant potential and arise from various benign processes. Adenomas represent the most common neoplastic polyps and are subclassified by architecture into tubular, villous, and tubulovillous types. Tubular adenomas account for approximately 70% of cases, characterized by simple glandular structures with low malignant potential in small lesions but increasing risk with size and villous components. Villous adenomas comprise 5-15% and feature elongated, finger-like projections, conferring the highest risk of progression to adenocarcinoma among adenomas. Tubulovillous adenomas make up 20-25%, blending features of both and exhibiting intermediate risk. Serrated polyps form another key neoplastic subgroup, distinguished by a saw-tooth glandular pattern and varying cancer risk. Hyperplastic polyps, the most frequent serrated type, are typically small, distal, and carry a very low risk of malignancy (<1%). In contrast, sessile serrated lesions (also called sessile serrated adenomas or polyps) are larger, right-sided, and have a higher progression risk of 5-15% due to their precursor role in the serrated neoplasia pathway. Traditional serrated adenomas, rarer and often left-sided, show mixed serrated and adenomatous features with elevated malignant potential. Non-neoplastic polyps include hamartomatous and inflammatory variants, which do not typically progress to cancer. Hamartomatous polyps, such as juvenile polyps (often solitary in children) and Peutz-Jeghers polyps (multiple and associated with a hereditary syndrome), consist of disorganized normal tissue elements like cystic glands and smooth muscle. Inflammatory pseudopolyps arise in inflammatory bowel disease, representing islands of regenerating mucosa amid ulceration rather than true neoplasms. Rare non-neoplastic types encompass lipomatous polyps, composed of adipose tissue and usually asymptomatic, and lymphoid polyps, which are nodular aggregates of immune cells. Metaplastic polyps, sometimes termed mucosal prolapse polyps, feature fibromuscular changes due to mechanical stress and are not true polyps but reactive proliferations. The World Health Organization's 2019 classification, which remains the standard as of 2025, refined polyp taxonomy, particularly elevating sessile serrated lesions as a distinct entity from hyperplastic polyps owing to their differing molecular profiles and cancer risks, aiding in targeted surveillance. This update underscores the role of BRAF mutations and CpG island methylator phenotype in serrated pathways, distinct from the APC-driven adenoma-carcinoma sequence.Comparison of histological features

Colorectal polyps exhibit diverse histological features that distinguish their types and inform clinical risk assessment. Non-neoplastic polyps, including hyperplastic, inflammatory, and hamartomatous variants, generally lack dysplasia and show benign architectural patterns, whereas neoplastic polyps such as conventional adenomas and certain serrated lesions demonstrate cytological atypia and structural abnormalities indicative of malignant potential. These differences are critical for determining progression risk, with neoplastic types progressing through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence or serrated pathway to colorectal cancer.[4] Key histological differentiators center on the presence of dysplasia and architectural complexity. Neoplastic polyps like adenomas feature dysplastic epithelium—ranging from low-grade in tubular forms to high-grade in villous subtypes—arranged in glandular or frond-like patterns, conferring substantial malignant potential that escalates with villous components or size exceeding 1 cm (approximately 10-20% risk of harboring invasive cancer). In contrast, non-neoplastic polyps such as hyperplastic types display uniform serration without dysplasia, while inflammatory polyps exhibit stromal inflammation and surface erosion, both with negligible progression risk (<1%). Hamartomatous polyps, characterized by malformed but mature tissues, also lack dysplasia but may signal syndromic associations elevating overall cancer susceptibility. Among serrated polyps, sessile serrated lesions stand out with boot-shaped crypts and lateral growth, bridging non-neoplastic and neoplastic categories due to their potential for dysplasia development.[47][48][4] Prevalence among endoscopically detected polyps reflects these distinctions: conventional adenomas comprise 60-70%, hyperplastic polyps 20-30%, inflammatory polyps around 10-20% in inflammatory bowel disease contexts, hamartomatous polyps less than 1%, and serrated lesions (including sessile subtypes) approximately 20-30% overall, with traditional serrated adenomas rarer at 1-5%.[4][49] Diagnostic challenges are prominent in borderline cases, particularly differentiating hyperplastic polyps from sessile serrated lesions, where subtle features like crypt base serration or dilation may be overlooked in superficial sections, leading to interobserver disagreement rates of 20-40%; exhaustive sectioning and immunohistochemical aids are often necessary for accurate classification. Multidisciplinary review is recommended for complex or diagnostically challenging polyps, prioritizing histological confirmation to guide risk stratification without over-resection.[50][51]| Polyp Type | Histological Features | Malignancy Risk | Location Preference | Approximate Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperplastic polyp | Serrated crypts with regular architecture, no dysplasia | Low (<1%) | Distal colon/rectum | 20-30% |

| Sessile serrated lesion | Serrated architecture with crypt dilation, horizontal extension, possible low-grade dysplasia | Intermediate (5-15% if ≥1 cm or dysplastic) | Proximal colon | 3-9% |

| Tubular adenoma | Branched tubular glands with low- to high-grade dysplasia | Variable (1% if <1 cm; 10-20% if >1 cm) | Throughout (distal for small) | 50-60% |

| Villous adenoma | Leaf-like villous projections with high-grade dysplasia | High (20-40%) | Distal colon | 5-10% |

| Hamartomatous polyp (e.g., juvenile) | Disorganized admixture of glands, stroma, and cysts; no dysplasia | Low (<1%) | Variable | <1% |

| Inflammatory polyp | Surface erosion with inflammatory granulation tissue and fibrosis; no dysplasia | Very low (<1%) | Areas of inflammation (e.g., IBD) | 10-20% in IBD contexts |