Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Mucus.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mucus

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Mucus

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

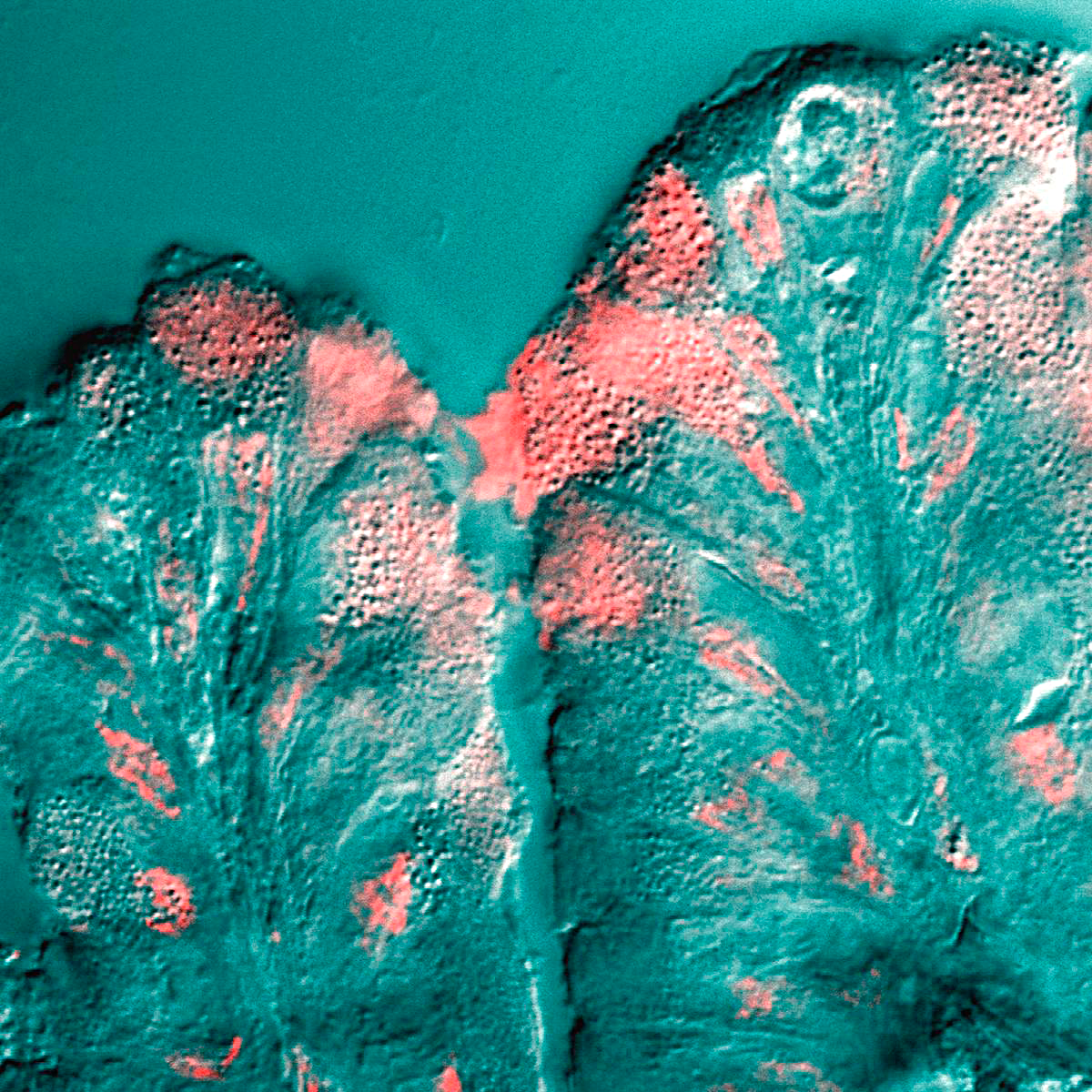

Mucus is a viscous, gel-like substance primarily composed of water, mucins, salts, lipids, and cellular debris, secreted by specialized epithelial cells to form a protective hydrogel layer on mucosal surfaces throughout the body, including the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urogenital tracts.[1] This slippery secretion, typically 97-99% water with mucins making up about 0.5-1% of its solids, provides lubrication and hydration to prevent tissue desiccation while acting as a physical barrier against environmental insults.[2] Mucins, the key glycoproteins in mucus, are high-molecular-weight proteins heavily glycosylated with carbohydrates (75-90% by mass), enabling the viscoelastic properties essential for its gel-forming structure and encoded by genes such as MUC5AC and MUC5B.[3]

Produced mainly by goblet cells in the epithelium and submucosal glands, mucus is synthesized in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus before secretion via exocytosis, often stimulated by inflammatory signals like cytokines (e.g., IL-13) or neural agonists.[1] In the airways, for instance, it traps inhaled particles, bacteria, and viruses—up to 10^6 to 10^10 daily—facilitating their removal through mucociliary clearance, where cilia beat at 10-20 Hz to propel the mucus layer at rates of about 50 µm/s.[2] Beyond mechanical defense, mucus supports a diverse microbiota by housing trillions of microbes, regulates immune responses, aids wound healing, and in the stomach prevents self-digestion by protecting the epithelium from acidic contents.[1] Dysregulation of mucus production or hydration, as seen in conditions like cystic fibrosis where mutations in the CFTR gene lead to abnormally thick mucus, underscores its critical role in maintaining organ homeostasis and preventing infection.[4]